Sunspet camera and matching sunglasses, photo: Carol Dass, gift of the artist

Mark Sink is a native of Colorado and has left a giant imprimatur on Colorado photography—as a photographer, organizer of salons, historian, magazine contributor, editor/publisher and founder/curator. His retrospective at RedLine Denver is an astounding look at his own personal history—not only well beyond his own life as a photographer via his community impact, but also his unique position as a descendant of the some of the most important pioneers of photography in the America, including his great-grandfather James L Breese Sr—the man responsible for the daguerreotype process being implemented in the US after he saw Daguerre speak about the process in Europe. Breese was also one of the visionaries of the Camera Club of New York (1897-1903). In Mark’s own practice he embraced the photographic technology of his early days the ‘60s/’70s/’80s—like xeroxes, the Diana camera, polaroid—to the present, recording his vision/his life as well implementing other more historic technologies like the cyanotypes and collodion wet types, among others . . . And Mark has an important history with his involvement with magazines . . . In both Colorado and beyond, as well as salon culture . . . What follows are responses about Typed Live, Excuse Errors . . . A Mark Sink Retrospective. On view through April 9th, 2023 at RedLine Contemporary Art Center, Denver, CO. Artist’s walk and talk, April 1, 2023, Noon-1pm.

Interview by Devon Dikeou

The exhibition at RedLine is organized in groups and then subgroups within . . . Please talk about the organization of the exhibition . . . And specifically the influences and circles that encompassed your rich photographic heritage . . .

Starts wayback machine . . . my roots . . . and takes you through all the connecting dots that formed me . . . I was calling it my tree of life but that was too corny . . . but I love trees . . . I was an arborist in high school and college. So it’s an inner connection of family history and community and art.

I have been wanting to tell the story of my crazy family history for some time. Mom’s Breese side starts way, way down there in NYC . . . with NY harbor master Rev Sidney Breese buried at Trinity church in the mid 1700s. My dad is from Ohio.

The show starts with painter and inventor Samuel Finley Breese Morse who took one of the first photographs in America. He is considered the “Father of American Photography” and taught Matthew Brady how to make images. His nephew James L Breese was the “primary inspiration” of the Camera Club of NY . . . His late-night salons were a wild, wild forward bunch. Scientists, inventors, leaders of women’s suffrage, queers, black musicians, female modern dancers, painters and photographers . . . Remember this is the 19th century . . . His daughter Frances “Tany” who I’m CRAZY for was an early critical modernist, abstract painter, raced cars, and hung out with a queer crowd . . . She opened NYC’s first modernist interior design stores, built the first modernist house architects’ row in Bridgehampton, NY . . . on and on . . . dumped her banker husband and married a beautiful black Haitian man . . . that was an eye opener for Southampton society. She taught me how to swim in the ocean in 1967 the same month Andy Warhol and crew stayed there filming The Loves of Ondean. We signed the guest book right next to each other! Andy was VERY surprised when I told him.

Breese’s son James L Breese Jr (my grandpa), inventor and engineer, flew across the ocean eight years before Lindbergh (May 1919)—front page of The NY Times “First Across” big hero of the time, ticker tape parade and all . . . funny how history can forget . . . Well, JLB was not long for NYC being that he married an Irish redhead Maggie Malone . . . Old Aunt Pussie (yes, her name was Pussie) threw him out of the family and inheritance. He eventually landed in Santa Fe, New Mexico, during the depression . . . bought a ranch on Upper Canyon Road . . . welcomed by other local easterners Gustave Baumann and dashing painter Randell Davey—both very close to the family . . .

Believe it or not this last summer a wheeler/dealer secondhand store picker in a Salvation Army in Santa Fe found 12 albums, full of 2,700 images of our Breese family NYC to Santa Fe 1880s to 1950s, Wright Brothers first flights . . . JLBs fight across the ocean (taken with his camera!) and the Santa Fe art scene starting in the 1920s . . . Mind-boggling . . . oh and the cars and cars and more cars . . . The Breese’s beloved cars . . . part of the reason the family threw them out . . . Mechanics were not proper . . . especially woman driving!

It’s hard to accurately tell the crazy story of how all these things came together just this last summer . . . magic really . . . First was the very unexpected discovery of the Breese family albums 1880-1950s. Secondly, right at this time I had some automobile historians doing a deep dive story on Breese from the point of view of his cars . . . This is when I came to find out the Breese brothers developed an aluminum race car for The American Sportsman. It was called the BLM Runnabout (Breese Lawrance Mouton), Henry Ford even inquired about it at a New York auto show in 1907 . . . Anyway . . . I found a French Lithograph of an advertisement of the car from a historical foundation in Paris and had the high-res scan sent . . . for I was extra excited the model driving was my aunt Frances (Tanty) racing on cliff edge . . . and if that wasn’t enough, to my mind-blowing surprise, when high res file came through found the artists signature was Frances’s close friend Otho Cushing . . . a super queer artist sidekick of Tanty and Breese Sr.

James L. Breese, Zephyr, The Carbon Studio, 1897, courtesy of Mark Sink

And the Triumph . . .

Cars are in the Breese line from the very start . . . from the first car races ever (Ormond Beach) . . . and co-founding of the AAA. Coast to coast road trips in the Model T. With my Triumph, the story goes—I had ridden my bicycle down to Santa Fe to help up my reclusive aunt NC Breese (mom’s sister living in Grandpa Breese’s house on Upper Canyon) . . . and in the garage I found under a dirt-laden blanket a rare first edition Triumph TR2 . . . love at first sight . . . it took the whole summer of slow, hard work to talk my aunt out of it . . . I went to town got a battery . . . filled the tires with a bike pump . . . and . . . Like in the Woody Alan movie Sleeper (with the VW he found in the cave) . . . the car started! It was a very exciting moment driving that car back to Denver.

Within your work is a real sense of printed matter/magazine as part of your practice, from your work on Criss Cross magazine—Clark Richert’s publication to your own publication The Codex (with Eric Havelock-Baille and Reed Weimar, 1983-1986) which is simultaneous to Parkett and certainly Interview (all early ‘80s) . . . please give us an insight to how publications reflect your practice. I’m so grateful to always see these histories of magazines . . . Because as Codex is so aptly titled, for certain periods of time they are our history . . . Our codex.

Yes, The Codex . . . the first bound book . . .

Many over-the-top firsts happened for me while at Metro State College. What a great time for many of us and art in Colorado. This is when tuition was just a few hundred dollars (1970s/1980s). You could easily work it off in “work-study.” One of many jobs, I worked in the photo lab cage. Working in the photo lab was good timing because we did lots of all-nighters in the lab making wild and experimental prints and just barely getting cleaned up before the first morning classes started. Early days of video . . . This was the time of our wild all-nighters. I was always in trouble. Blamed for breaking video equipment. A group of us were experimenting with making videos with the manual f-stop and shutter creating wonderful effects neg to positive . . . I found I could then project the negative capture with a cardboard box over the monitor/TV and with a toilet paper tube as a lens projects onto large color photo paper on the wall. Wonderful results (as published in Clarks Colorado Arts Newspaper). I have all these videos and prints. A print from my video still projector is up at RedLine now.

The first Codex was conceived in 1982 and was surely one of the first correspondence art publications in the region. A majority of the publication was xerox and photography related, in the mid 1970s to early 1980s. I was doing a lot of Xerox copy art at the Auraria campus, produced in large out of the Auraria Campus library. I would unplug the xerox machine and roll it into the small study rooms. There I would set appointments in my new private studio office and make portraits and figure work, while also making florals and still lifes on the glass predating today’s scanner art. Out of this came one of the first Xerox as fine art shows in Denver at Phil Bender’s Pirate Art Oasis, circa 1981. This was my first venture out in the real art world.

I have several hundred Xerox street handbills from this period. Phil Bender’s Denver DaDa Club, The Pirate Art Oasis, and all the rock and punk bands that played the Denver ‘80s music scene. I have a Dropbox link of it all for those interested DM me. I did a paper called, “Did DADA die?” comparing street punk art hand bills and posters to DaDaCabaret Voltaire era (1916) hand bills and posters. Leading up to this (1977-78) Clark Rickert and others in a group called Criss Cross were publishing an artist I have great interest in, Ray Johnson, and EF Higgins who made Xerox correspondence art. This was published in Criss Cross magazine out of University of Colorado, Boulder. I have been doing a deep dive with Ray Johnson recently, and Andy Warhol who was also experimenting with Xerox at this time. And around 1982-3 Jean-Michel Basquiat was using Xerox copiers.

In Sept 1981 I met and became friends with Andy Warhol at Colorado State University in Fort Collins, Colorado. He hired me on the spot. I was on Interview magazine’s masthead the next month. I also worked for Jean-Michel till his death. This explosion of NYC high art excitement was brought back to school and into the darkroom to video art and projects like The Codex.

I was very interested in the concept of correspondence art and publishing it. Greatly inspired by The International Society of Copier Artists (ISCA) copy artists and mail art . . . and Art Life out of UC Santa Barbara. With the “Lets Do It” inspiration of artist friends, Eric Havelock-Bailie and Reed Philip Weimer, the codex was formed. The Codex was a portfolio, a book, a periodical of entirely original work. Anything in multimedia was accepted, copy machine art encouraged along with photography and printmaking and the written page . . . poetry etc. The work could be taken out and exhibited as an exhibition. Purchasers of the book were encouraged to frame the original work. It’s filled with some of Colorado’s finest talent. Four volumes were published from 1983-1986. The Codex has been taken in by several major museum bookstores including the Denver Art Museum, The Guggenheim Museum, and fine art bookstores like Printed Matter in NYC . . . Franklin Furnace and City Lights in San Francisco. From the beginning, the primary inspiration of the Codex was from correspondence with the ISCA—wonderful typed letters and mail art sent from Louise Neaderland who encouraged me to continue my copy machine art and publication ideas.

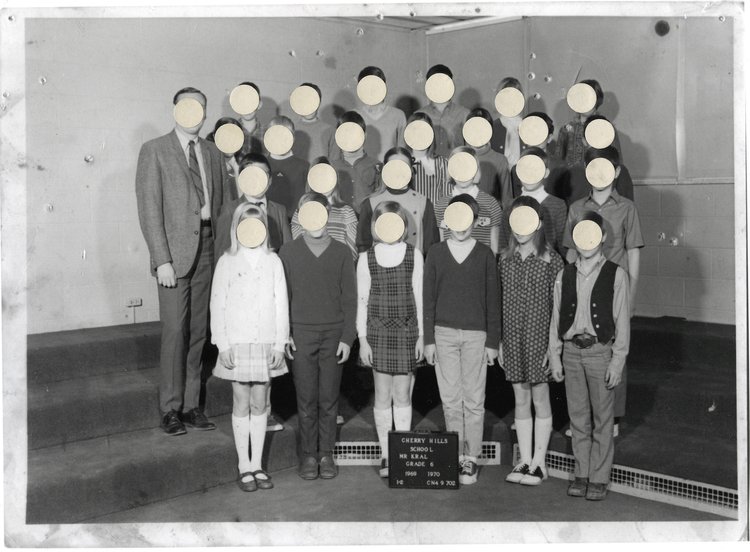

Mark Sink, Third Grade and Dots, 2021, silver print with vinyl dots

And you hung in the grooviest circles in downtown NYC, as Colorado correspondent for Interview . . . Talk about ALL that was . . .

Well, that’s a book in itself . . . the ‘80s are so hot right now . . . who woulda known? . . . Early ‘80s and arriving at the Factory I first thought Andy was a bit washed up . . . sort of gone model Hollywood glamour, and all of his new print series done out-of-house—contracted with a commercial screen company . . . Jean-Michel was also not in very good shape in the mid ‘80s . . . It was not as glamorous as many make it out to be . . . I was just a worker bee, there with my lens and film . . . a fly on the wall watching the excess play out like some surreal play . . . always lots of drama . . . Like today still there is a big gulf of the have and the have-nots . . .

It was surreal and empowering and beyond belief for me in my early twenties . . . Andy would send me to shoot famous events like Denver’s Carousel Ball . . . Andy LOVED my shots of all the stars. During my early, crashing-big-events days in the early ‘80s, billionaire industrialist Marvin Davis who owned 20th Century Fox had his contract stars come to his hometown Denver for a great ball his wife put on. I just jumped the rope and got right in there, right in their faces, a foot away, with a 50mm lens . . . bright flash boom . . . shot many dozens of stars and politicians, agents . . . and worked my way right in and up into the VIP room, I said Andy Warhol sent me “Interview Magazine” . . . With the press outside I hung out with Donald Sutherland and the Dynasty cast . . . Dolly Parton super-agent Swifty Lazar! . . . Thousands of images. Andy was very jealous. A few will be in my retrospective. I have other nutty stories of the Davis family, Nancy Davis is my age. I wonder what she is up to . . .

I helped shoot parties of new advertisers in Interview and at the same time opened new accounts to distribute the magazine and was always, always looking to land ads. I assisted Chris Makos with an interview photo series “New Faces in the Rockies.” I was hoping New Faces was going to become my own column . . . but I moved to NY instead. I soon realized the genius in all of Andy’s glamorous ventures . . . and his Andy Warhol TV and Love Boat . . . it was art of our times . . . My love and respect for him re-emerged before his death.

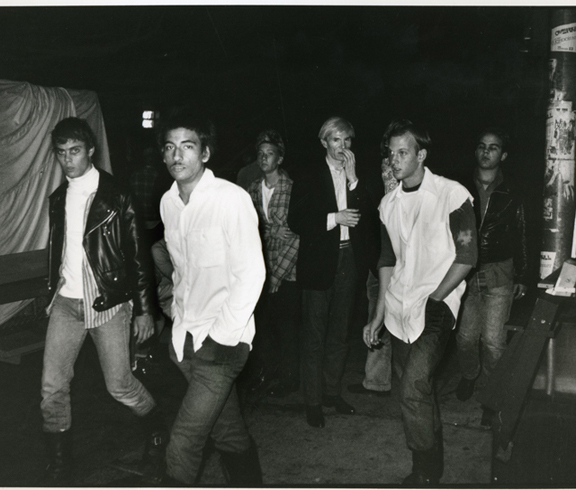

Mark Sink, picking up Andy to go on a date to the Odeon, March 1982, pigment print from Kodachrome slide

I am grateful that I got to know Jean-Michel and call him a friend. He was a very complicated soul and that is clearly expressed in his work. He is one of the most pure, free and unique artists to emerge out of NYC in 1980s.It really hit me in 1996 the major impact on our creative society JMB left us with when I went to a giant shopping mall mainstream movie theater full of people to see a big-screen movie about the life of a young black artist in his twenties. It’s amazing to see how his spirit and inspiration has carried on into the millennial generations of young emerging artists today.

I first became fully aware of JMB when visiting my friend, photographer Chris Makos, in 1981. Chris did a studio portrait of him holding a world globe on his shoulder and he purchased some of his drawings and prints like “famous negro athletes.” I remember Chris telling me this guy was rising really fast. In the early to mid ‘80s, I had a growing friendship with Andy Warhol. Once I called the Factory to speak with him about an upcoming trip to Colorado. Then front desk secretary who liked me, Brigid Berlin, patched me right through . . . He told me he was painting with Jean-Michel . . . I remember saying to say hello . . . I have that conversation taped I should check what else I said.

I first met Jean-Michel when I was visiting NYC and staying for long periods at the Hotel Chelsea to be near Andy starting in 1981. Stanley the manager called me “Alfred Stieglitz ” because I was always taking pictures. My first meeting with JMB was girlfriend Lynne Ida and artist friend Robert Hawkins. We were visiting a friend, actor Danny Kerwick, a bartender from Denver (from my days at a Jack Kerouac/Neil Cassidy hangout called My Brothers Bar). We met Danny at a small restaurant bar the Great Jones Street Cafe where he worked and managed. We closed the bar and stumbled out locking the door into the early morning. As we walked out Robert Hawkins saw someone across the street and yelled, “Jean!” It was some kid getting out of a limo . . . He waved and invited us over and into the studio door (later found out it was a former carriage stable owned by Andy Warhol). I had no idea who he was. Robert stood talking and I was looking around the messy painting studio. I asked if I could look at the paintings lined up in the racks nearby. As I pulled them out I slowly realized who it was . . . Robert was mortally embarrassed as I came to the realization we were with an art superstar . . . saying, Oh, you’re Jean-Michel Basquiat! . . . I, then star-struck, shamelessly asked if he would draw me something—which embarrassed Robert even more. But Jean-Michel loved it . . . he said sure and started with ballpoint pen a tail but then grabbed a long paintbrush dripping with thick red paint out of a coffee can and proceeded to paint a scorpion, then wrote Scorpio in the middle and then crossed it out and handed it to me. It was dripping with fresh paint so he took it back and printed it down the lower right corner of the canvas that we were looking at. (to dry the paint faster). I have always looked for that canvas with the lobster print on it but have yet to see it in any books. He then invited us to go out to the Brasserie a 24-hour haunt in the famous Seagram building uptown (it was around 3am). We jumped in the limo still sitting outside and had a ruckus ride up . . . smoking pot and drinking more . . . coke very well could have been passed around also. I was getting pretty intoxicated and blurry. The driver I believe maybe was the artist Shenge Ka Pharaoh who I am friends with today (on Facebook). I wish I remembered more about the breakfast and return home . . . I presumed that Shenge dropped us home at the Hotel Chelsea. Thank heavens I took pictures it probably would have all been lost to partying induced memory-loss.

I officially moved to NY in 1984 into a great stone flatiron building on One Hudson Street in Tribeca, a block away from the famous restaurant favorite of Warhol and Jean-Michel, The Odeon. I was working for a publisher friend, Gerald Rothberg, whose employment made the move to NYC possible. (Via shooting for Circus Magazine and MGF, Men’s Guide to Fashion). In the following years I would see JMB around town at art openings. At this time he often looked kind of angry, wired and disheveled—not wanting to be there or not have anyone approach to talk to him. A few times I saw him out at popular artist-favored restaurants. One time he was at a big table with the most beautiful girls in the room fawning over him. I was jealous. Mostly because I was broke and did not have a girlfriend at the time. It was hard for many of us struggling to survive at the time watching a friend become rich and famous and move on to a new glamorous orbit of beauty and celebrities. It was a left out feeling.

He came to a couple of openings at the Patrick Fox Gallery north of Houston (NoHo) where I worked and had a studio I dug out in the basement. I photographed the work and openings there for several years. It was across the street from Artforum magazine which was in the amazing white Louis Sullivan building. The gallery was located at 56 Bleecker . . . a 1700s brick farmhouse I was told was the home of Colonel Bleecker. I have great memories of a potbelly stove and giant skylighted tin ceiling and wall covered room called the Tin Room in the back of the gallery that was a hangout for many 1980s rising art stars and drug addicts. Also, critics like Rene Ricard and Cookie Muller and others. I did many thousands of portraits of them and the artists in that beautiful space. I photographed Jean-Michel with his girlfriend Suzanne Mallouk during one opening. He lived just around the corner on Great Jones Street. I would see him walking around time to time. He’d wave and smile.

Once at a dance party in the basement of downtown restaurant club called Indochine on Lafayette Street I was dancing with my girlfriend Pam Edelstein. He saw me waved. I was excited he made the effort to come over to talk with us. We talked about building a house with adobe mud and if I would help him (I told him I had just returned from Santa Fe building an adobe house with my sister). He scribbled his number on a napkin and said to come by. Little did we know I would be coming over many times to photograph his work later that year. He then lit up a giant cigar-size marijuana blunt dripping with hash chunks and handed it to me through a giant cloud of smoke . . . then he proceeded to dance off with my girlfriend. The night ended with jealously poisoning my blood as I watched my girlfriend denying his advances to leave with him.

Andy Warhol had died Feb 22nd, 1987 . . . some days after I saw Jean in the street . . . we stood together in the middle of Houston Street waiting for cars to pass. He was very angry . . . he never worked out his anger and the fallout he had with Andy after the collaboration and show at Tony Shafrazi’s gallery. It was poorly received and he was pissed cause Andy said he was helping Jean’s career, and Jean felt he was helping Andy’s sagging career. Standing there in the traffic he told me he was really, really mad at Andy and that he was freaking out cause he never got to resolve it.

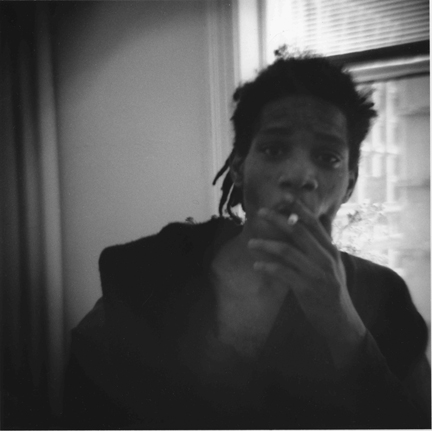

Mark Sink, Jean-Michel Basquiat smoking at the Vreg Baghoomian Gallery, September 5, 1988, silver print

Around this time I started working photographing artwork and events for the Iranian art dealer Vreg Baghoomian. He was a cousin of the famous dealer Tony Shafrazi who infamously spray-painted Picasso’s Guernica at MoMA. I had to carry big eight-foot-tall priceless Jean-Michel and Cy Twomblys and other canvases out into the windy crowded sidewalk for several blocks and back . . . just for viewing (so they would not to be seen in each others’ galleries). Vreg liked me for some reason. I was told he was the accountant or finance minister for the Shah of Iran in the ‘70s and had to flee. He had intense anger streaks. I witnessed many outbursts and I lasted through two full staff firings. Vreg was very frustrated with Jean-Michel leading up to the last show. He kept having to send him large amounts of cash . . . and then he did not hear from him for weeks at a time . . . He was panicking when it was getting closer to his show . . . I believe he was first in Europe than in LA hiding. But the paintings made it there that spring and the show got mounted . . . I was photographing them on my old school large-format view camera (8 x 10″ transparencies) when Jean dropped in. His painter friend Ouattara Watts was there also. I asked him to sign the exhibition poster . . . he drew a mouse with a lightning bolt from the eye to the words “Terry Lennox”. I have never known what that refers to maybe the pretty female local artist named Terry Lennox? Or a good fit is a movie The Long Goodbye. A murder mystery story of a character Terry Lennox who had gone missing and was murdered in Mexico. I wish I had asked him. I photographed him drawing on the poster and hanging out together with Ouattera. This was April 1988.

I photographed his famous “Amateur Bout” notebook of words at the studio and various other drawings. He often had lots of other drawings and things he wanted to be photographed and I would stay longer after I shot the major paintings . . . he once offered me a drawing for my extra time working . . . I declined . . . (a top life regret). I told him I wanted to build up credit for a small painting.

The most well-known image I took of him was in June 1988 . . . I was documenting the exhibition before it came down and he happened to drop by. I had my large view camera out . . . and asked him to stand very still in front of the canvas. He by chance happened to stand in front of the words, “Man Dies”. On Friday, August 12, Jean-Michel Basquiat died in his Great Jones Street loft at age twenty-seven.

Looking for Leon . . . Again here I go digging into my ‘80s tubs, dusty boxes of contact sheets and Kodachrome slides looking for the moments with a lost hero.

Always loved this line—“My eyes are starving for beauty”. André Leon Talley, Jean-Michel, Grace, and Andy, it’s hard to believe I knew them, hung out and even dined on occasion. It’s kinda out of body looking back now. In the mid-80s I was very lucky to dine one evening with Leon at the marvelous surprise performance restaurant Raoul’s in SoHo. Senior Vogue editors (Elizabeth Saltzman and Jackie Spaniel) had sent me. I loved and frequented this art-filled haven. One night was with publisher friend and employer Gerry Rothberg of Circus Magazine and Men’s Guide to Fashion. We witnessed a performance of the shower scene from Hitchcock’s Psycho by the owner. My solo sitting with Leon . . . he gave me a moment . . . a long look hello but I never made it in . . . I am just too slow to match his fast wit. We talked of Warhol and how Andy had helped early working for Interview Magazine. I believe the Vogue girls also knew I had crossed paths with Diana Vreeland thanks to my superhero Factory friend Fred Hughes. Fred, the wizard behind the curtain, oversaw much of Andy’s Factory empire. I visited Fred often, he took me to fashion shows and introduced me to princesses in the kitchen of his home (Andy’s first home). He loved my old NYC family stories more than anyone I ever met. I had shown Fred my great grandfather’s 1890s Carbon Studio portrait album at the Factory. He jumped out of his skin excited of the old New York gilded age sitters before him . . . This is the kind of thing he loved, old old money. He knew everyone. The maiden names, “That’s Winston Churchill’s mother! That’s the Posts and the Parsons! And Miss Emily Hoffman!” He picked up his antique black dial phone and called up Diana Vreeland and left a message. “I have a young man here with beautiful pictures of your mother you must see, can I send him over?” (I had no idea Miss Hoffman was Diana’s mother). Later in the day when I was back down in NoHo at the 56 Bleecker gallery the phone rang in the Tin Room . . . this was a great moment I will never forget in front of the gallery crew . . . “Mark, Diana Vreeland would like to speak to you . . .” We set up a presentation and to my surprise, she asked to use the images for the Met Gala. I have a memory of asking a stupidly low price. But I did get a ticket to go. Sadly, she did not think highly of my great grandfather, and abruptly hung up the phone once. He among other things uncivilized was credited by some to be the fall of his close friend Standford White. Soon the studio and its Carbonites came under fire as a secret place of lascivious intrigue . . . that’s another chapter . . . the epic murder of Stanford White.

I have written a lot about Andy. How we met and my time with him. How he took my calls and took me on a few dates. How I nearly killed him by accident while snowmobiling in Aspen. How he changed my life. I was kind of a depressed kid afraid of the world. He opened the door of belief in myself. Words can’t really express how lucky I am to have known him and called him my friend. The Factory kids were pretty petty and evil to me. When I ran an errand for Andy they gave me the wrong address so I would be hopelessly lost . . . upsetting Andy it took so long. They also told me to NEVER accept a gift from Andy . . . that it was just a test of ladder climbing loyalty or not . . . so on my birthday Andy offered me a gift from the “gift closet” I turned him down . . . he was sad . . . he told me later when I told him I was being pranked he said, “Oh good, I thought you did not like my work!” I did not get another chance.

Mark Sink, Andy in LA at Danny’s Dogs, 1981, silver print

Artists friends around the Patrick Fox/56 Bleecker Gallery. I hope to do a book about the Tin Room:

Carl Apfelschnitt

Was a brilliant painter that I photographed work of in trade. He died of AIDS in the late 80s. He describes his hands-on, raw approach to abstract painting as the “expressionistic” work of a “primordial monster”. He was best known for abstract paintings with a strong physical presence, whose thick, poured surfaces were often marked by cracks and craters. #carlapfelschnitt

Chris Makos

Chris is a close friend, famous photographer, sidekick and photo printer of Andy Warhol. One of the funniest and most interesting people I know. Chris burst onto the photography scene with his ‘77 book, WHITE TRASH. This raw, beautiful book chronicled the downtown NYC punk scene. @christophermakos

DAZE 0

Chris Daze Ellis was born in ‘62 in New York City. He began his prolific career painting New York City subway cars in 1976. We are close friends and we talk often. He is a fabulous photographer. I have brought him to Denver a couple of times to exhibit. His career is booming internationally, including doing work with some top fashion houses. @dazeworldnyc

Edward Brezinski

A charismatic Lower East Side painter on the fringe of success I photographed his work in trade for many years. He was picked on by other artists in his circle . . . until he got his show at MoMA. #edwardbrezinski

Felix Pène du Bois

I have several major works/paintings she gave me. . . I helped her out of some tough times. Once she was assaulted in New Orleans, and Robert Hawkins and I drove her paintings that she had to abandon back to her home in Boston. She was a fixture of 56 Bleecker Gallery in the 80s, who gained recognition for portraying allegorical scenes inspired by the city life around her. “Felix’s paintings are a source of light,” critic and poet Rene Ricard wrote in a lively essay on Pène du Bois—therein only referred to as “Felix”—for Artforum’s September ‘86 issue. “This is an artist who has learned how to make pictures shimmer and they would work if they only had their paint, but they also take us to faraway places and advertise a vivid and personal world that is a vacation for the heart and an antidote for eyes poisoned by the toxic by-products of art history.”#felixpenedubois

Gerard Malanga

Poet, photographer, filmmaker, actor, curator, and archivist. I did many projects with. He was the printer for Warhol in the 60s. He hired me for several amazing documentation projects. @gerard_malanga.official

Keith Haring

Keith was very kind to me . . . he was everywhere around town and at all the clubs all the time. Very accessible and very friendly even when he rose to a celebrity . . . he drew on my bicycle light once (since stolen) . . . he drew on my swatch watches and traded art for documentation. #keithharring

Mike Berg

Longtime friend I shot a lot of his work in trade . . . I have wonderful pieces I live with every day. He was once represented by RULE in Denver and has shown at The Boulder Museum of Contemporary Art. He is a great painter and sculptor . . . he got a great loft early . . . moved to Istanbul after 9/11 and now is back in NYC and he and his career are doing well. “Berg is a kind of aesthetic anarchist, disrupting the natural processes of decay and organizing his interventions into exquisitely layered abstraction.” – Linda Yablonsky @whos_mikeberg

Nic Rule

I traded for documenting his work. He has done well. He is in collections worldwide. Recently reviewed by Jerry Saltz in New York Magazine: “Rule paints words, families of words, naming words. (In the past, he has worked with genealogies and “bloodlines.” @nick_rule

Rene Ricard

Rene is my superhero. I think he is one of the most important figures coming out of the 80s. He discovered Jean-Michel, Julian Schnabel—who was just a short order cook, of course Keith Haring and countless others. I have a lot of great memories . . . some upsetting some that touch my heart. One foot in the gutter and one foot in royalty. Rene came to Denver a couple times for Robert Hawkins’s show at the Lynne Ida Gallery in the early 80s . . . he loved Denver and in particular El Chapultepec. Ricard’s landmark essay, “The Radiant Child” for Artforum defined the East Village gallery scene of the early 80s. This essay is credited with launching the public career of Jean-Michel Basquiat, as well as naming Keith Haring’s ubiquitous “crawling baby” character. In addition to Basquiat and Haring, the essay also highlights the work of Judy Rifka, John Ahern, Ronnie Cutrone, Izhar Patkin, Joe Zucker, and other artists showing at the numerous independent New York art exhibitions of the period. #renericard

Robert Hawkins

One of my best friends, Robert is a brilliant artist with a wonderful macabre dark sense of humor. Robert comes to Denver and exhibits often. He has shown at Lynne Ida Gallery, MCA Denver and currently has a great permanent climbing tower in Boulder at Seidel City where a large body of his work is in the collection of Terry Seidel. He most recently showed at MoMA NYC. Robert is the one who introduced me to everyone in this exhibition. We lived together on and off in Denver and NYC. I documented his work in trade for much of the ‘80s. Hawkins is best known for his “ferocious” style of realism. During the 80s, Hawkins created a presence within the early 80’s art scene in lower Manhattan. His first group showing titled “Three Americans” at Club 57 was with fellow artists Edward Brezinski and Brian Goodfellow in ‘81. In ‘80, Hawkins participated in a group show at the Mudd Club Gallery at the Mudd Club curated by Keith Haring. Hawkins’ first solo show was at the Anderson Theatre Gallery in ‘83 curated by art dealer Patrick Fox, who would represent Hawkins throughout the 80s. Fox opened the Patrick Fox Gallery in ‘83, where Hawkins had another solo show. In ‘85 Hawkins had a solo show at the Lynne Ida Gallery in Denver, Colorado. That year, Hawkins also had a solo show at Alexander Wood Gallery in New York. Hawkins then participated in a group show with artists, Jack Barth, Vincent Gallo, Bruce Mellett and Gustavo Ojeda at the Luhring Augustine and Hodes Gallery in New York in ‘85. In ‘86, Hawkins had another solo show with Patrick Fox and at 56 Bleecker followed by a collaborative show with the fashion designer, Stephen Sprouse at 56 Bleecker Gallery in ‘87. “Dead Things by Living Artists” was Hawkins next ‘87 show at Bond Gallery in New York. @robertodellh

Scott Covert

Scotty and I have been friends ever since we met in the mid ‘80s. Again I provided high quality slides and transparencies for trade for work. His career is doing very well. He stops in Denver time to time while he is criss-crossing the US from LA to NYC to FL. He was a founding member of Playhouse 57 at the storied Club 57. Incorporating the everyday method of “rubbings” to transcribe epitaphs from graveyards and mausoleums, Scott Covert creates text-driven drawings and paintings that engage collective consciousness and reference a wide range of human experience. @the_dead_supreme

Scott Kilgour

Ever since the 80s Scott has stayed in touch and even dropped by my home recently where he gifted me the piece. His work is based on knot-work designs, that embark on a decade-long study exploring the spatial relationship of continuous line drawing in Scottish Celtic Interlace. @kilgourscott

Sylvia Martins

Sylvia is a Brazilian painter I traded with. A beautiful smart woman. She studied at the School of Visual Arts in ‘78 and at the Art Students League of New York from ‘79 to ‘82. She has shown work in solo and group exhibits around the world. For a number of years she dated Richard Gere, before marrying billionaire Constantine Niarchos in ‘97. Her paintings are mainly abstract. Richard gave her a giant Jean-Michel painting. @sylviammartins

Stephen Sprouse

Stephen was a fashion designer and artist credited with pioneering the 80s mix of “uptown sophistication in clothing with a downtown punk and pop sensibility he ran with the fast pack. Warhol and Haring . . . Duran Duran. I met Stephen at the 56 Bleecker Gallery around ‘86. I photographed his work and some fashion. He gave me one of his leather vests in trade and a beautiful Iggy Pop painting presented in trade for a shoot of large transparencies of his paintings. He hung out with Warhol and I photographed them together with Polaroid. He was very kind to me and often invited me to dinner. @stephensprouse

Ouattara Watts

Ouattara is from Ivory Coast. He studied at l’École nationale supérieure des Beaux-Arts in Paris. In Paris, he met Jean-Michel Basquiat at an exhibition opening in January 88. Basquiat was impressed by Watts’s paintings and convinced him to move to New York City. That is where I met him with Jean-Michel and photographed them together and later I photographed his painting. We have stayed friends and comment time to time on social media. His career: He has shown with Gagosian Gallery and museums and foundations around the world . . . he made it to the other side. @ouattarawatts

Vittorio Scarpati

I live with this image of the dolphin visiting a sad man at the aquarium . . . it touches my heart. I traded for it photographing his show at 56 Bleecker. Vittorio was an Italian artist, political cartoonist and jewelry designer. He met art critic and actress Cookie Mueller (John Walters film star) in Italy, in ‘83. Three years later they married in New York City. Scarpati died on 14 September ‘89. He was 34. Cookie died a couple months later also . . . both of aids. It’s a very sad story.

Zabo Chabiland

Visual artist working across a number of mediums—installation, photography, sound performance, video and sculpture. She graduated from the full-time studies program of The International Center of Photography of New York in ‘88. Zabo is a fabulous amazing forward artist. A close friend faraway making art in France. She was a music mixing VJ, mixing music and projections on the spot from her laptop in the mid 90s . . . way, way early. It blew my mind and I said to myself that is the end of photography as we know it. He also made X-ray prints and black and black . . . black dark silver prints wet stretched on frames like canvas … great artist and friend I miss terribly. @zabochabiland

Mark Sink, Caitlin with flowers, 2012, collodion wetplate

Collaborations: photography can be both solitary and collaborative. Long hours developing film and editing it, other parts of photography are collaborative—you might have live subjects, both long elaborate sittings or quick, off the cuff snaps . . . Speak about your collaborations/collaborative spirit in terms of the show, from those with your wife Kristen Hatgi to your daughter Poppy, and to the more passive objective of simply recording time and place—say the Polaroids . . . Give us an insight in to technical challenges or techniques, from perhaps the more solitary perspective, but perhaps not . . .

From start to finish I am a portrait photographer . . . Inspired by Andy I shot everything everywhere, anything the moved . . . thousands and thousands of rolls. For the last five decades, I have been expanding my understanding of portraiture using a wide range of experimental and alternative processes, sometimes obsessively. The thread that connects a large amount of my portrait work is long exposure, the act of “holding still,” a concept, which reveals what is most important and present in his subjects. A person is more “there” that has to hold still. The Diana is a simple plastic toy camera with that was first manufactured in the 60s. I have had a long, almost 30-year relationship with Diana. She was with me before and through my period at Warhol’s Factory, even though Andy hated the camera. It was too “old fashioned looking.” Diana got me into New Yorker, Vogue and Details and my first solo show in NYC in 1986 titled, “Twelve Nudes and a Gargoyle.” And cooperate accounts such at Wells Fargo, Putumayo clothing and Dial soap even.

Andy loved my Polaroid work . . . The ‘80s were a wild explosive period for me in the city. I became friends with many rising art stars because I photographed their artwork and I extensively documented the scene at openings and in artists’ studios. During this time I started using Polaroid SX-70, and stumbled upon a method of making unusual Polaroid portraits. Lucas Samaras showed me ways to manipulate the Polaroid to make extraordinary images. I found you could cover the light meter and fool the camera’s shutter to stay open. During this extended exposure I could paint light onto the sitter. What a wonderful new mission. I could now spontaneously approach a celebrity artist and ask if I could take a Polaroid. Ninety nine percent of the time they said yes because of the Polaroid’s innocent appeal. I would ask the person to hold very still for eight seconds while I bathed them in small bursts of light, what I call light painting. It was a kind of performance, with me moving around the subject while painting light in. The sitter usually stayed to see the magic of the Polaroid, and upon seeing the photo signed the bottom and often asked for more. The Polaroid was a great calling card and opened many doors for me. I see these Polaroids as a wonderful small document of the 80s NYC.

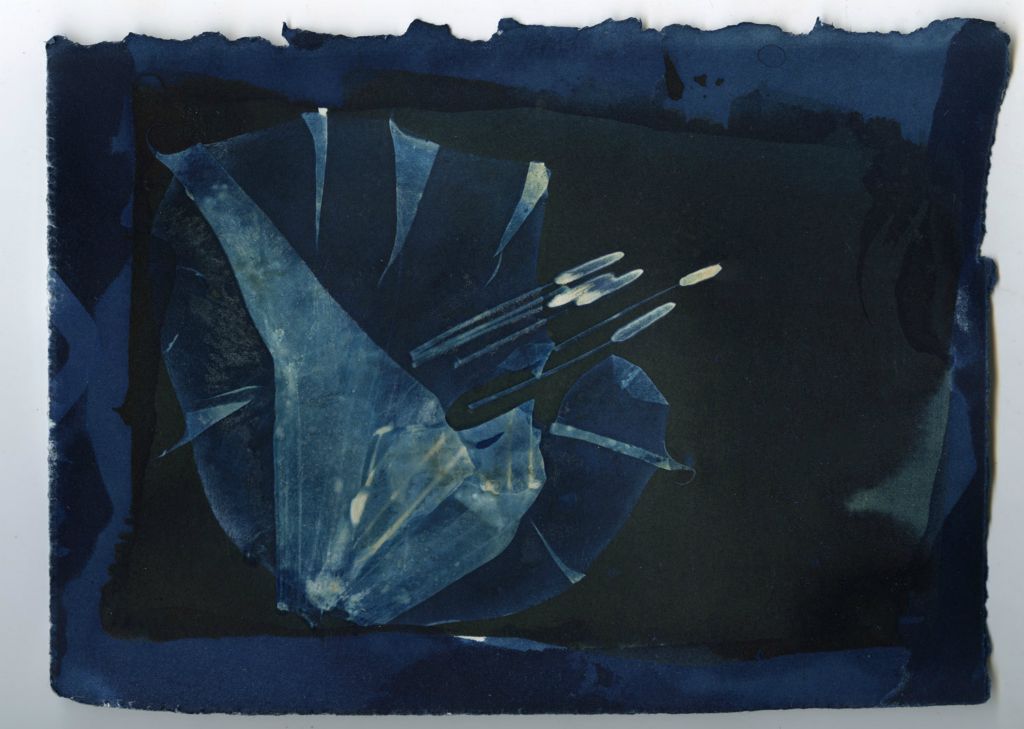

The basic cyanotype recipe, where prints are developed outdoors by the sun, has not changed since scientist Sir John Herschel introduced it in 1842. Julia Margaret Cameron, a close friend to Herschel, sought to master the process through her portraiture and, like the Sinks, decorates her familiar and famous subjects with costumes and adornments for extended poises. Both Herschel and Cameron are “heroes” and clear influences to our practice. Cyanotypes were notably used in Herschel’s era by Anna Atkins. Her floral work inspired us with Poppy, to make their (our)? cyanotype floral series.

My wife Kristen and I use the historic wet plate collodion process and antique cameras to create modern ambrotypes and tintypes. The photograph is created by pouring a thin layer of collodion on a glass or tin plate before sensitizing it with silver nitrate. Collodion on glass is known as an ambrotype; poured on tin it’s called a ferrotype or tintype. This process was developed by Frederick Scott Archer in 1851. Among famous photographers who used it are William Henry Jackson and Matthew Brady (who learned the process from Samuel Finley Breese Morse). By the turn of the 20th century, new inventions such as film and paper prints had made image making far easier, and wet plates fell out of favor. Contemporary artists like Sally Mann, Scully & Osterman, and locally, Chris Perez, Hunter Helmstaedter, Sink & Hatgi, are at the forefront of its revival.

I am known for working within a romantic tradition and in these color still life works from the early ‘90s. I was inspired by Dutch Old Master still life paintings of the 1600s. In particular Rachel Ruysch (1664 – 1750). They show beauty in the light of life as well as in death. The whole drama of the life cycle unfolds before your eyes; flowers, vegetables, bugs and animals populate the image while in the dark recesses there are worms, snails, the dead and dying being recycled back into the earth through decomposition.

Photograms are images produced without a camera or enlarger. I lay objects directly on photographic paper, then expose it with a flash of light and develop it in the dark room. I use simple, meditative objects for these photograms because sometimes the things closest to you can be the most beautiful. Light traveling through the glass of a wine goblet or a bottle creates endless new surprises. Flour, salt, pepper and dust exposed on silver gelatin paper become vast universes of infinite detail.

Mark and Poppy Sink, Flower contact prints, 2021, cyanotype

That talk of collaboration brings us to what I’ll call your salon/club effect. . . Your great grandfather, James L Breese Sr, began a salon in NYC, “One of 1001 Nights” at Camera Club of New York, that included some of the best coteries of New York society—Stanford White, Nicola Tesla, John Singer Sargent to name just a few. You have been involved with clubs or salons—an integral part of your practice from the Denver Salon to Denver Collage Club (with Mario Zoots) even to the Month of Photography . . . Please end our discussion with the history and nature of these gesture’s importance, and the collaborative communication of it all . . .

It’s really what my life story is . . . this show is all about it. I have been collecting people into salons before I even knew what I was doing. Maybe it’s an insecurity about my own work and needing a team to bolster me? Maybe I am just inspired by great talent, and want to promote it? It’s in my DNA—like Breese gatherings of explorers around you. The people on the edge, the queer, the disenfranchised, one foot in the gutter, one foot in royalty . . . The misfits, mixed with society’s royalty. Makes the best parties ever . . . and people remember great parties. You can see the thread and everything I do from the first meetings in my backyard for MCA Denver or the Month of Photography or the Denver Salon or the Denver Collage Club, it’s power in numbers, even with the Month of Photography, we formed an international group called the Festival of Light that is interconnecting all the photo festivals around the world together. I just can’t help myself. Then when the organization gets up and going it’s a job.

Now I’d like to move on to my last big salon mission. Picture this as a giant archive and gallery space for all of us retiring artists. Not a museum, not a library, kind of a purgatory, simple safe house for future generations who may one day dig into . . . be in a salt mine or old missile silo. That’s just part . . . the big dream is a giant arts retirement center that old people can teach young people to grow beautiful gardens with a big cooking center at its heart, media labs to watch great old movies. Pottery and sculpture made with your hands. I would really, really, really love to see this through . . .

Installation view of with Wardrobe: Curatorial AIRspace Residency 2022–23 Exhibition, February 11, 2023 – April 9, 2023. Photograph by Olympia Shannon. Image courtesy of Abrons Arts Center.

Laura Serejo Genes & Kiyoto Koseki are a curatorial partnership based in New York who produce exhibitions and programs for specific sites, building upon existing systems to draw new social, material, and historical connections. As Curatorial AIRspace Residents for 2022-23 they present with Wardrobe, a group exhibition at Abrons Arts Center featuring works by CFGNY, Devin Kenny, Erika Ceruzzi, K8 Hardy, Keioui Keijaun Thomas, Ken Lum, and Pope.L. The exhibition is on view through April 9, 2023, with performances by Keioui Keijaun Thomas on April 4 and Devin Kenny on April 5.

Interview by Brandon Johnson

This exhibition explores a complex intersection of art, fashion, and performance via a collection of artists that “incorporate elements of dress sourced from global systems of material trade.” How did your curatorial duo link up, and what paths led each of you to this cultural intersection?

We are both coming to curation as artists (and friends), but we see our curatorial endeavors less as an extension of our artistic work, and more as a natural outgrowing of the conversations we have maintained over the years. We share an interest in modes of indexing, and the form of the exhibition lends itself well to relational thinking across mediums and time periods.

As temporary “residents” of Abrons Arts Center, it was important for us to critically analyze the history of the neighborhood and the institution itself, both for ourselves and for the exhibiting artists. This was facilitated by the fact that the parent institution of the center, Henry Street Settlement, has played a significant role in the community for over a century. In particular, we gravitated towards histories of local garment production and the theatrical costumes that were collected from the Playhouse Theater. Some may be surprised to learn that The Costume Institute at The Metropolitan Museum of Art was actually started by founders of the historic theater, or that early garment manufacturing in the Lower East Side was done in the homes of workers until larger factories replaced this model.

Thematically, we were also thinking about dressing as an aesthetic act that we all participate in when engaging in public space—clothes as the medium that carries us between private and public spheres. Continuing that line of thinking, garments also act as signifiers for specific communities and social categories themselves might be thought of as “byproducts” of commercial enterprises. In a way, dressing and/or undressing is inevitably performed inwardly and outwardly.

I love the fundamental connection of this exhibition to the history of the site at which it takes place. In fact, the title of the exhibition, with Wardrobe, is sourced from a passage in Henry Street Settlement’s founder Lillian Wald’s memoir. In a greater sense, what role do you see history playing in the practice of curation? And more specifically, how did it play into your thinking and planning for this exhibition?

“Site” can be a bit broad as a term and it often describes spatial conditions alone, but you could think of “neighborhood-specificity” or “institutional-specificity” as a way of acknowledging a local history. For us, the site has to be material, temporal, and social.

That being said, our intention wasn’t for Lillian Wald’s memoir to serve as a central reference; we like how literary cues refer back to a source while taking on a life of their own. “With Wardrobe,” which refers to the inclusion of coat check with admission to an event, is also a phrase no longer in popular use—a fact which lends it an interesting ambiguity. Both in theater or at a special event, the act of shedding a layer can reveal and activate another. This idea of layering comes up as a recurring curatorial strategy as well.

Installation view of with Wardrobe: Curatorial AIRspace Residency 2022–23 Exhibition, February 11, 2023 – April 9, 2023. Photograph by Olympia Shannon. Image courtesy of Abrons Arts Center.

While at the exhibition I took note of site-specific installations by Erika Ceruzzi engaged with as you say “idiosyncratic architectural details” within the Abrons Arts Center exhibition space. And with further reading I now understand that CFGNY’s installation The Family (2023) is also site-specific, making use of antique wooden chairs from Henry Street Settlement. Being a sucker for site-specificity, I commend you and would like to hear more about your collaboration with these artists to execute these works . . .

We clearly are too! We set the field for the exhibition at the center to include Henry Street Settlement and its headquarters, which is housed in three conjoined 19th century buildings. This was another form of thinking about connections through time as well as space. We originally approached CFGNY to exhibit a selection of items from their clothing line, but the collective became very interested in Lillian Wald’s progressive politics and lifestyle, and the framing of her story within queer history. (Henry Street Settlement was recognized by the New York State Historic Preservation Office as a LGBT Historic site in 2021.) Using antique chairs from the headquarters, they created a circular arrangement that seats 25 unique stuffed animals, recalling the chosen family Lillian lived and worked with. The combination of cartoonish characters, Colonial-style furniture, and Brutalist architecture creates a temporal mashup that bridges decades.

On her first site visit, Erika Ceruzzi expressed interest in an interstitial space alongside the stairwell to the Upper Gallery. This “tub” was a perfectly de-programmed space, in the sense that most of the employees and modern users of the building could not say what the space was originally intended for. Responding to this site, she made a work out of muslin, the material used for making clothing patterns. It’s beautifully taut. She used nails, plastic buckles, and decommissioned machine hardware to provide this particularly satisfying tailored look—a soft service for a hard architecture. Erika collected the hardware accessories seen across the works during one of her residencies at a sock factory where she produces custom tube socks, a commodity that reoccurs in her work.

Installation view of with Wardrobe: Curatorial AIRspace Residency 2022–23 Exhibition, February 11, 2023 – April 9, 2023. Photograph by Olympia Shannon. Image courtesy of Abrons Arts Center.

On that note, what was your process for selecting the rest of the artists? Did you observe a trend that fed into your thinking around the show that these artists demonstrated? Or did you search out artists who interested you and then shaped your thinking in more of a feedback loop? In either case, curious as to how this roster came together, as well as how you feel the concerns of this exhibition relate to our current culture and society at large…

The selection process was quite mixed and it was shaped over some months, as we wanted to allow the site to feed back into our decisions. We were also mindful of how the center has framed art as a social service or as “arts for living,” which made us think about the exhibition in relation to community health, both in subject matter and in practice. This made Pope.L’s work important as a reference, as it explicitly responds to social ills, including what he describes as conditions of “have-not-ness.”

We gravitated toward Ken Lum’s work due to its reference to advertising and its ability to work on a scale that would take advantage of the visibility of the gallery walls from the street. In our conversations with Ken we learned that part of his family lived in the Lower East Side, right on Henry Street for some time after emigrating from China. Small, yet sentimental, details like this aided in our decision-making.

Although she is originally from Texas, K8 also has deep ties to the Lower East Side. Her work embodies the idea of “trendsetting” with a true humor and confidence that feels particular to the downtown scene and important to capture for discussion. Her monumental Untitled Runway Show, which was presented at the 2012 Whitney Biennial, continues to influence the art and fashion worlds alike, and we knew we wanted to exhibit at least a pair of “looks” from the collection.

Overall, we are especially happy with the lines of connection made between the artists and works that could not have been predicted. These connections feel both in and out of our hands in some regard, and maybe some of the magic is in this unpredictable constellation that forms as small decisions are made with a loose but larger picture in mind.

Installation view of with Wardrobe: Curatorial AIRspace Residency 2022–23 Exhibition, February 11, 2023 – April 9, 2023. Photograph by Olympia Shannon. Image courtesy of Abrons Arts Center.

There will be two performances: Keioui Keijaun Thomas’s Come Hell or High Femmes: The Era of the Dolls and Devin Kenny’s “It’s the new style!” or “No more aggregatekeepers”. What role do these performances play in with Wardrobe?

We are very excited for these performances, as they expand upon the artists’ contributions to the exhibition and allow them to present concepts latent in their sculptural work in a more interactive manner. The venue also offers a unique opportunity to extend the exhibition into spaces designed for performance. It’s a special touch that the theater-goers have to walk through two levels of the exhibition to make their way to their seats. The architecture really served us well in all its idiosyncrasy—we can thank the architect, Lo-Yi Chan for that!

Finally, seeing as the exhibition was the result of an annual curatorial residency at Abrons Arts Center—what did you learn from this experience as curators?

The multifaceted context of the center challenged us to consider audiences in a different way, beyond the commercial or academic formats and tones we were more familiar with. While the exhibition exists as a backdrop to a buzz of activities taking place daily at the center, it can also serve to redirect one’s path or one’s gaze. We welcome this overlap of dedicated and serendipitous experiences, as it supports our interest in generating unexpected connections between artworks and their sites of display. These conditions allowed us to think more broadly about physical and figurative access points throughout the exhibition, taking into account the sizable windows and views from the street.

Our residency actually continues with a group exhibition opening in June at CC Projects on Allen Street featuring the work of Alex Dolores Salerno, Emily Manwaring, Nina Macintosh, and Shirt—current artists in residence at the center. There is definitely a shared experience across all users of the center and it will be interesting to see how this comes through off-site.

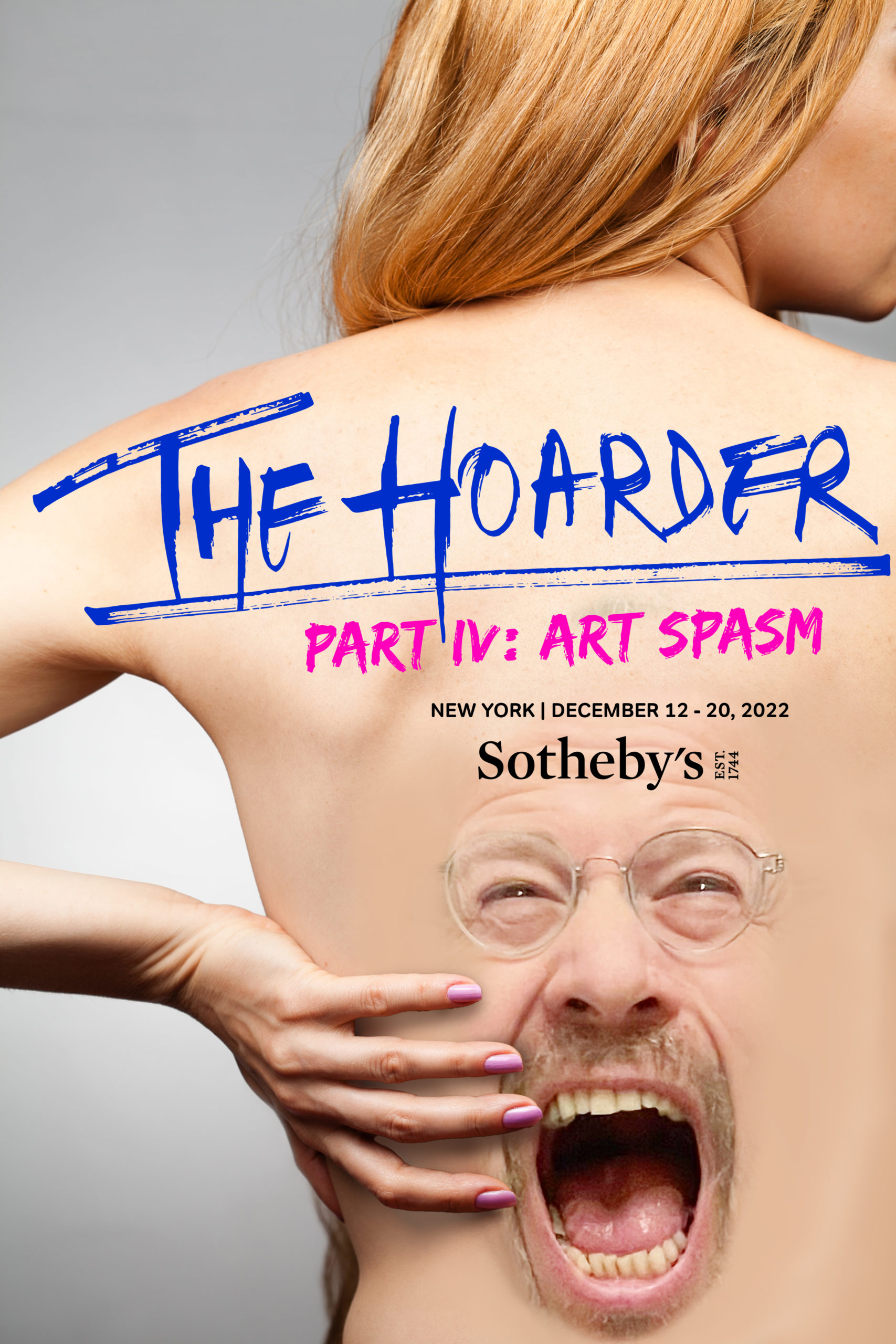

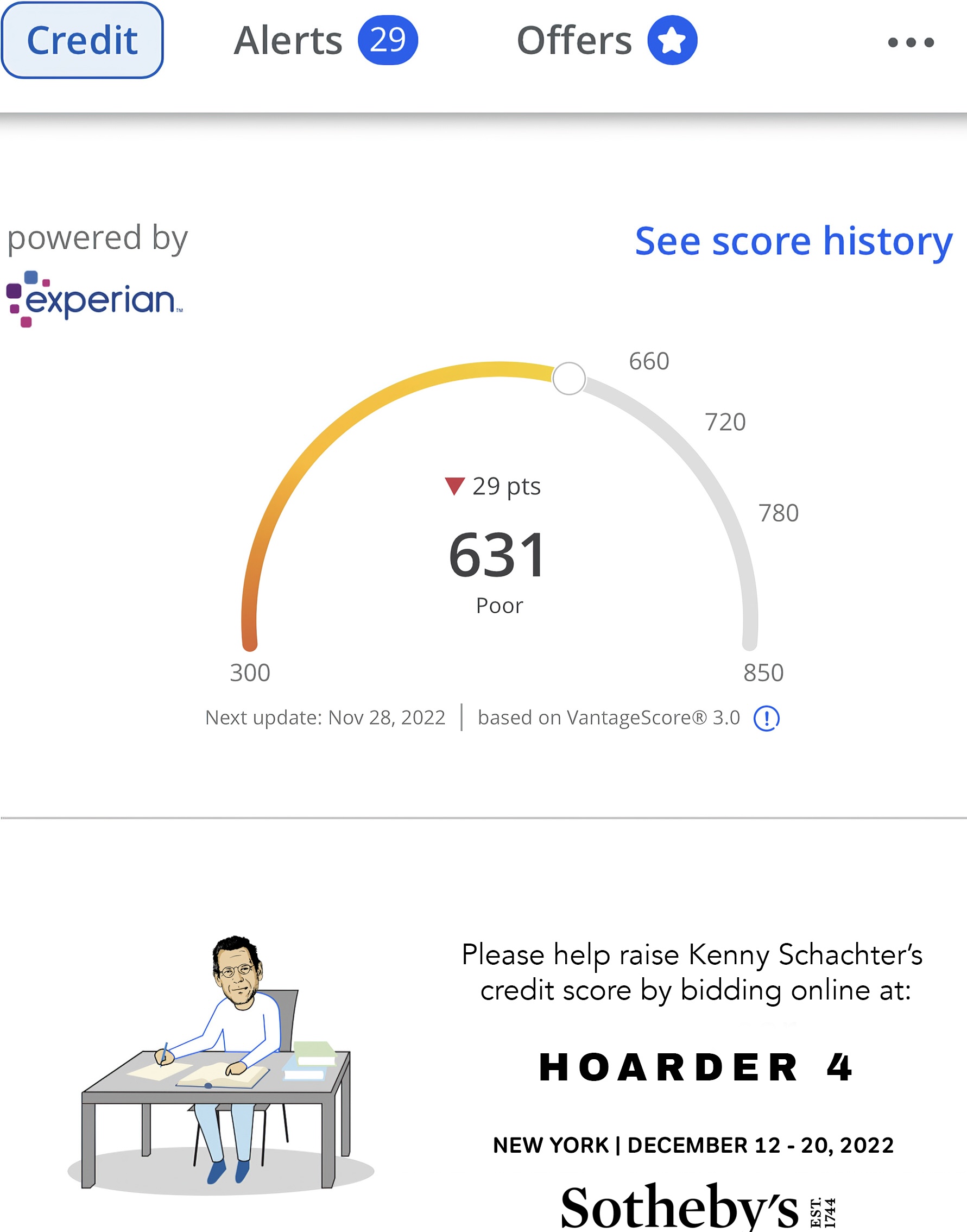

Kenny Schachter’s The Hoarder IV: Now Or Never sale will happen with Sotheby’s New York from December 12-20, 2022.

Interview by Devon Dikeou

Can you talk about the concept of Hoarder IV (already the fourth edition!) your sale at Sotheby’s—how did the idea get hatched?

I lived in London for 15 years before moving back to New York in 2019. When I took stock—or tried to—of the task of packing up my residence which had become inundated with stuff to the extent I thought the house would sink into its foundation, or I would be suffocated to death by my possessions, it was nothing short of daunting. And a little shameful. The idea occurred to me that a chunk of the art and design would be better served with new buyers that could cherish the works as I had. Before I got buried. Hoarder is a pejorative term for accumulating art which instantly appealed to me. And having utterly no reserves, unheard of in the auction world, seemed a great way to make art accessible to others that may not be in a position to afford to forge a collection. My loss is your gain.

How does one reconcile selling if one’s a hoarder . . . It seems counterintuitive . . .

Trust me, there’s never an empty wall in my house—even after 72 works were recently picked up from my place in NY. And that constitutes less than half this year’s sale. My storages have storage. I am materialistic yes, but ascetic too: as long as there is something I love to replace an object gone missing, I am copacetic. I don’t get too attached to individual things other than a handful of artists that form the core of my passions and interests. Plus, buying is addictive—it’s one of my only vices left at this stage of my life (other than cookies)—so there’s always incomings. And yes, I fully recognize the extent of my unresolved “issues.”

How does one decide what’s in the sale vs what one holds back?

Timing is important (i.e. when I bought something) so as not to get branded as a flipper though I am very laissez faire in life and think it’s normal for people to change their minds when it comes to ownership and don’t begrudge others who sell my art. Also, of all the works that have recently departed my hoard, there are things I couldn’t yet do without as they fulfill a function in my thought process at a certain point in my life.

How many of these sales have you done and how many should we expect?

This is the fourth and I planned to have it as the last but alas, I can’t really make a fulltime living from my art, writing and teaching (unfortunately), so what choice have I? Stay tuned for Hoarder V.

How does your specialty NFT’s figure into the mix . . .

It doesn’t . . . exactly. Though (I am full of self-contradictions) I am doing a mini-hoarder NFT sale with Lempertz Auction House in Germany on December 3rd. With no reserves (of course) and 13 lots.

Is the sale an art piece?

Everything I do—teaching, writing and making things—is in some sense related to my art process, a kind of performative exercise in self-sabotage.

Why Sotheby’s over Christie’s . . .

I had a nihilistic friend working at Sotheby’s in 2019 and he laughed when I proposed naming the auction derogatorily in relation to the stuffiness of the art world. At the time, online sales were the lowest of the auction hierarchy; one small step above selling your wares on a blanket on a street corner. So no one really took notice or cared. Then, in the face of the pandemic, online became the only way to transact art—for buyers to get their fix. At that point, Hoarder was already launched and as far as auction houses are concerned, if there’s a market for soiled underwear, then knickers they will sell. As long as my shit keeps selling, I’ll continue to have a platform and free reign.

Photo: From the Hip Photo

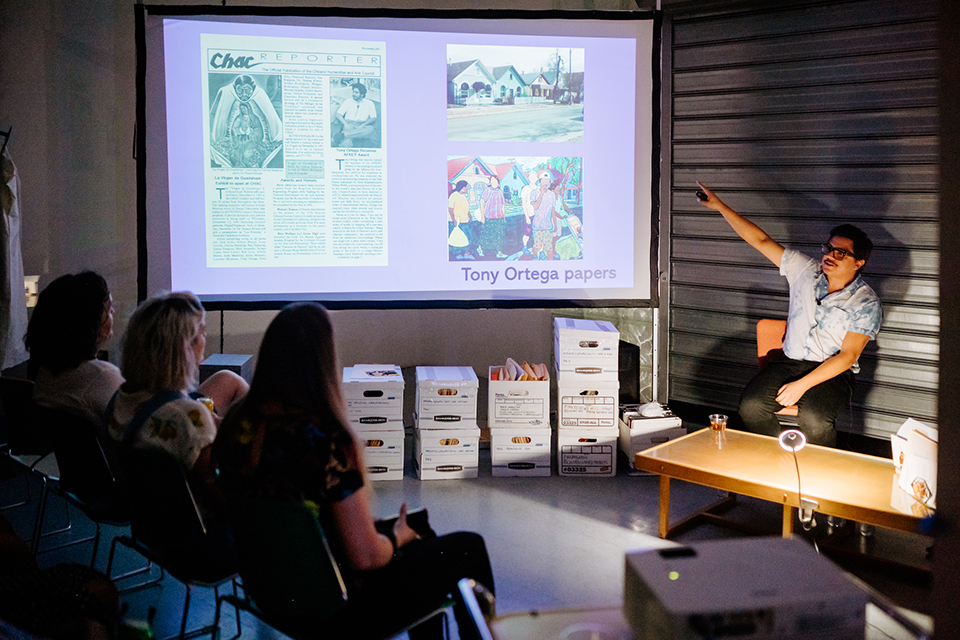

Josh Franco is an artist, art historian, and former zing contributor from West Texas. He has exhibited across Europe and the United States and will be publishing his first book, Marfa, Marfa: Rasquachismo and Minimalism in Far West Texas with Duke University Press later this year. Franco joined the Archives of American Art in 2015 as the Latino Collections Specialist and was recently appointed the Head of Collecting. On September 8, 2022, he sat down with Devon Dikeou for Archive Live—a series Franco conceptualized that puts artists in conversation with archivists and the public—to discuss her personal papers before they are sent to the archives in Washington D.C..

Interview by Paige Hirschey

The AAA has such an expansive mandate—to document the history of art in the United States—how do you determine which artists fit into this history? What goes into that process and who is a part of that conversation?

We have a thorough collections plan, most recently updated in July 2021. The plan is informed by our previous decades of collecting as well as rigorous discussion among staff (many, many drafts sent back and forth in the process). This collections plan lays out the intellectual framework and seven broad themes that help us organize our thinking when considering a new collection: lives of artists; research and writing about art; arts organizations; art market; patronage; art instruction and services; and miscellany. To quote the document, “While collections must have high research potential, as a national repository, the Archives seeks to represent the geographic scope, as well as racial and ethnic diversity, to build a representative picture of the visual arts in the United States.” I want to emphasize that this scope goes beyond the artists themselves and includes fabricators, critics, collectors, curators, and art historians as well.

I love the concept of Archive Live and sharing that exciting moment of discovery with an audience who might not be familiar with archival research. Can you tell us a bit about how the idea for those events came about?

I remember exactly how this came about! Sometime during my first couple of years at the Archives, when my role was Latino Collections Specialist, I realized how profound the experience of the collectors can be. We spend so much time working closely with accomplished arts workers poring over often quite personal documents. This inevitably brings a level of intimacy and deep historical knowledge that is not the typical classroom or museum experience, or even the reading room experience, where researchers have direct access to the materials, but not their creators. It felt very unfair that the tiny number of us who do this work got to have that experience, and I wanted to figure out how to share it with bigger audiences. Thus, Archive Live emerged as an idea, and I am happy to have conducted them with Paul Ramirez Jonas (our pilot and a Dikeou Collection artist!), Andres Serrano, Vincent Valdez, and most recently of course, Devon Dikeou.

Photo: From the Hip Photo

At our Archive Live event at the Dikeou Collection, you showed the audience the letter in which Marcel Duchamp offhandedly coined the term “readymade,” which underscored how important archives are in terms of preserving materials that may seem insignificant at the time but ultimately shape our cultural history. This impulse is also central to Devon’s practice, in the sense that she foregrounds the documentation of her own personal and professional history. Does that shape the way you’re deciding what material of hers will ultimately go to the Archives?

There is an extra layer of interesting complexity when collecting the papers of an artist whose medium is itself the art world. Like Devon in her practice, the Archives is concerned with documenting the social networks, notable figures, and institutions that give form to the visual arts. All of the records created by Devon—from her own practice, zingmagazine, and the Dikeou Collection—perform this function, so in a way, it’s like we are nesting the archive she and the whole Dikeou team have created within ours. Worlds inside worlds, is one way to think of it.

On a related note, I would imagine that Devon’s work is presenting some interesting questions vis-a-vis categorization. How do you differentiate “art” from “archive” in a body of work where they so frequently intersect? Is this something you’ve encountered before?

Yes, we encounter this with some frequency in fact. It’s often something the artist hasn’t had to think about before we begin conversations about the Archives. Our base policy is that it’s up to the artist first to determine what is artwork and what is archival material. Once they make that determination, we see how the identified materials fit or don’t fit into our collecting scope. Because Devon has put so much energy into documentation and thinking about this question herself, it’s actually relatively clear with her papers where the line is. That may seem counter-intuitive, but I think it’s a logical result of her practice; while someone who is, say, strictly a painter may just be thinking of this distinction for the first time, Devon’s practice, which takes documentation and administration as its central raw material, has led her to think about these questions deeply and for a long time. Unlike a painter who might be considering the status of their drawings in these terms for the first time ever, Devon has thought about these questions for quite a while, as they’re fundamental to her work.

Photo: From the Hip Photo

How does working with a living artist, whose practice is still evolving, affect the acquisition process?

It can be a double-edged sword. On the one hand, thinking again about Archive Live, it is invaluable to have the artist available to provide greater context for a collection, as we can document that additional information and make it part of the record, benefitting researchers down the road. On the other hand, undergoing this task while still active compels an artist to think of themselves in the historical long-term, which can do some strange things to one’s sense of self in time, not to mention one’s mortality. Again though, based on her practice, this kind of thinking seems to already be integral in Devon’s approach to making art, so I’m not worried about any kind of de-railing in this instance. In fact, I imagine the whole process could be incorporated into a Dikeou artwork in the future—what would Devon do with our shelving system? Our Finding Aids? Our Reading Room protocols? It’s conceptually rich, but also just a lot of fun, to imagine these possibilities.

Devon has worn many different hats in the art world, she’s an artist, editor, and patron, she’s worked in galleries and has an international network of art world contacts. How do you think this might inform the ways that future scholars will use her papers?

That’s exactly why I feel a sense of urgency around this collection. Some of our most frequently accessed collections are those created by figures who create worlds unto themselves through insatiable curiosity and a compulsion to document and gather ephemera. I am thinking of the Lucy Lippard papers and the Tomás Ybarra-Frausto Research Material on Chicano Art, which are perennially in the top 10 of most used collections, out of around six thousand. This is because Lippard and Ybarra-Frausto, when you look at their bios, dedicated their lives to building networks and continually connecting and re-connecting different nodes in those networks…and holding on to all the associated scraps of paper generated and gathered along the way. They are multivalent, with an entry point for nearly any aspect of art history in the United States someone might be thinking about. What’s striking in Devon’s case is that she is herself an artist, which is not the case with Lippard and Ybarra-Frausto. I am eager to see what uses the Devon Dikeou papers, zingmagazine records, and Dikeou Collection records are put to in the future. Devon is not only an artist’s artist, but an art historian’s artist too.

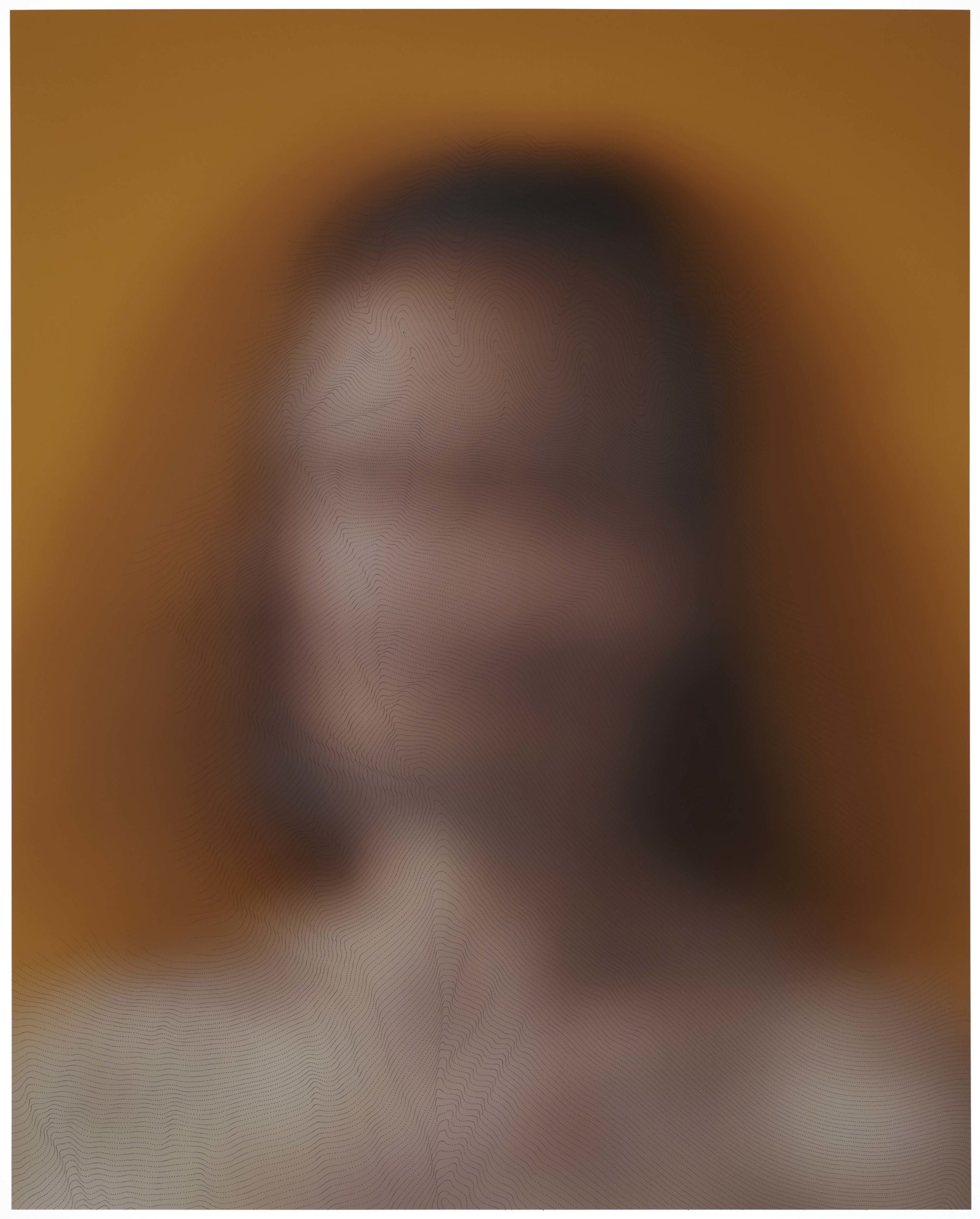

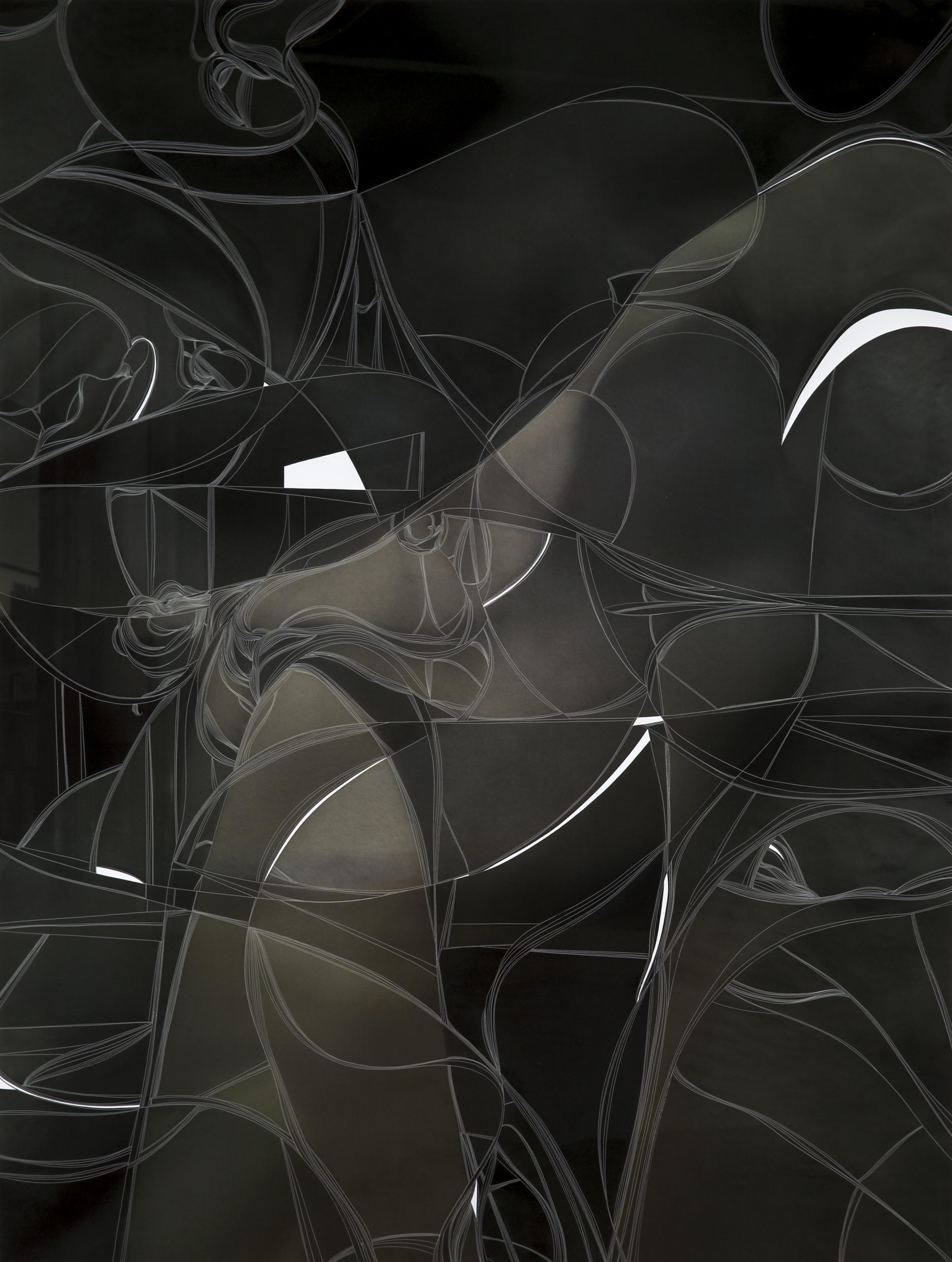

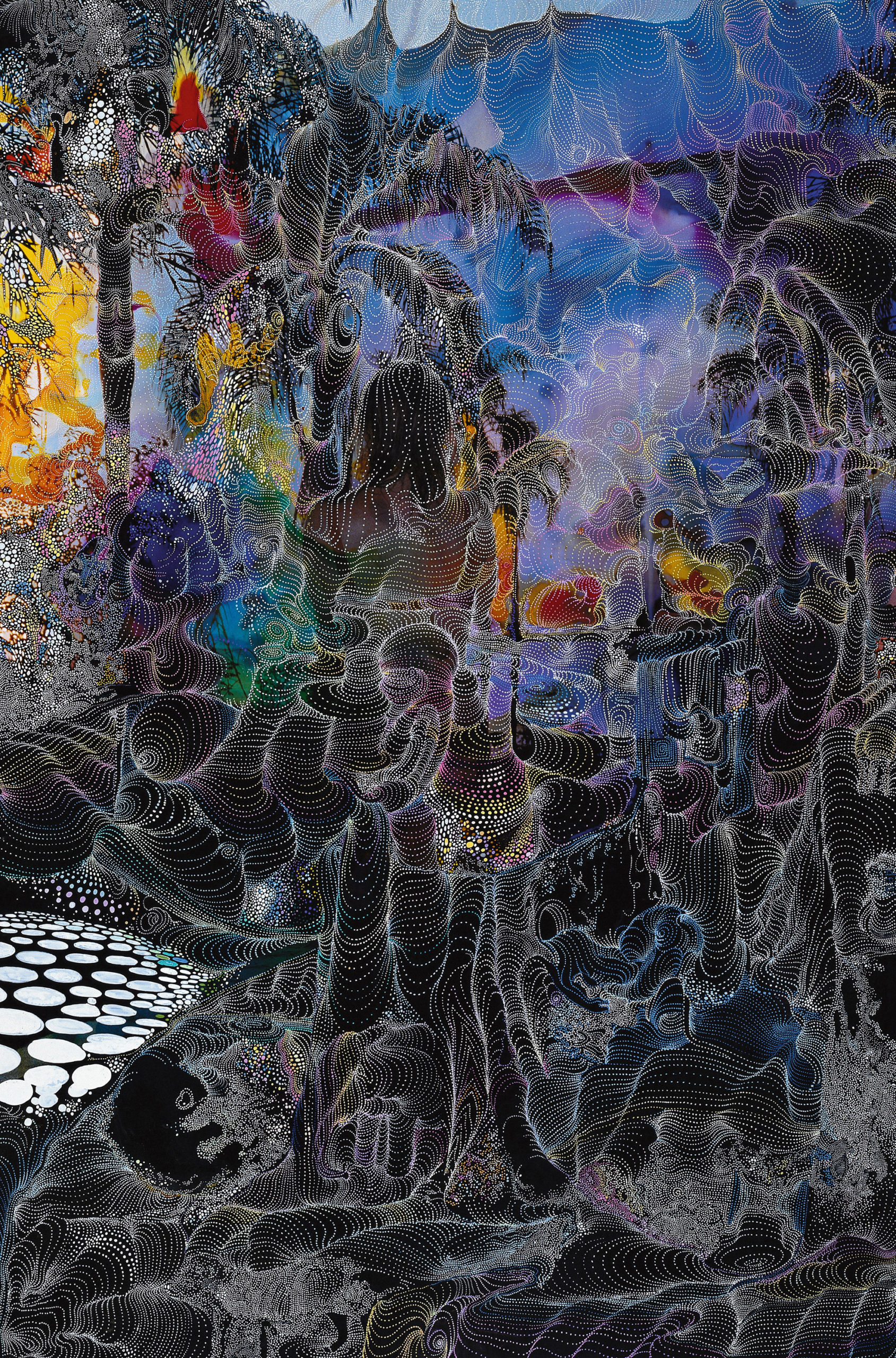

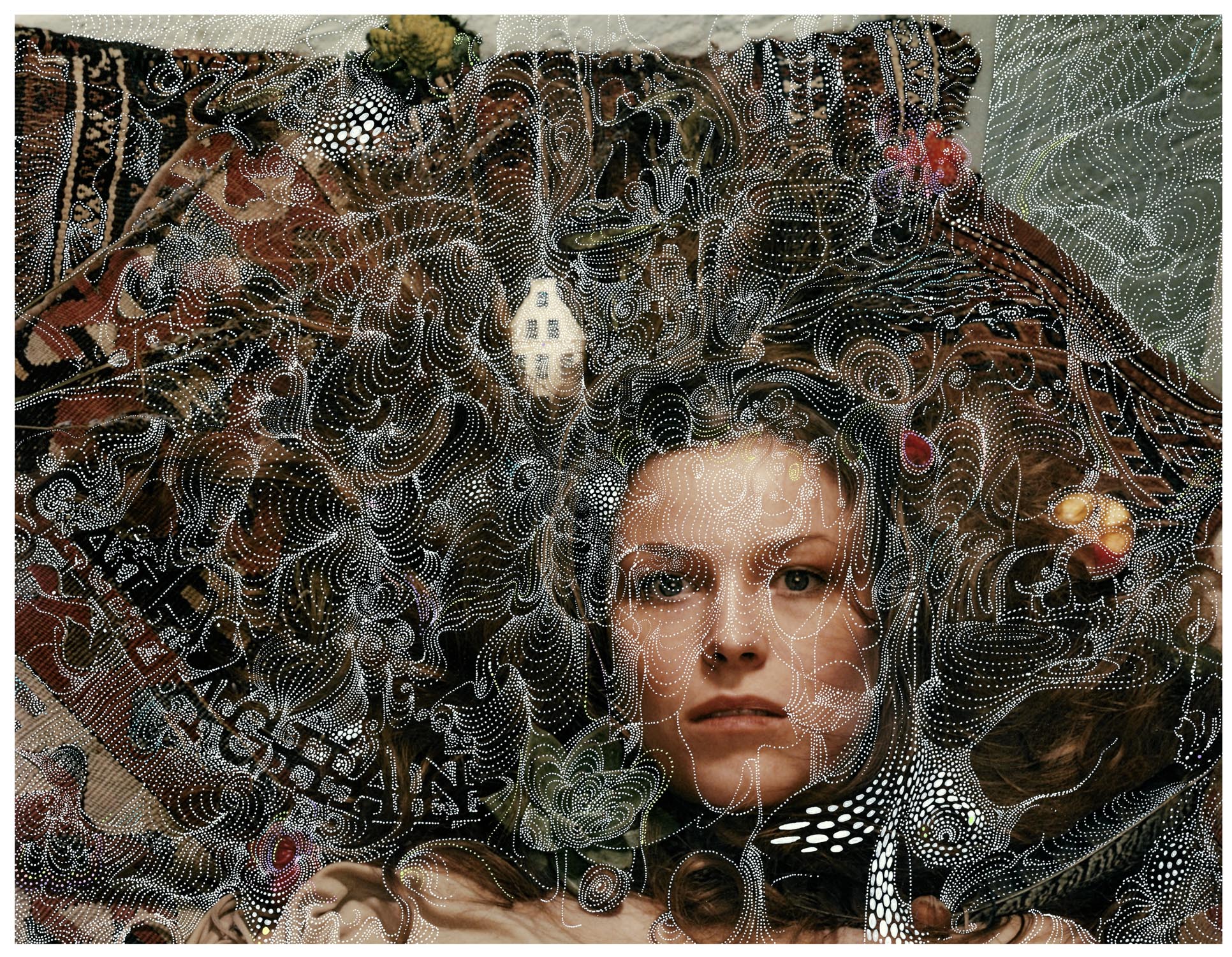

New Portrait: Pedro 1, 2022, ink on archival digital pigment print on paper, 36 x45 inches

These questions are posed to Sebastiaan Bremer on the occasion of his fall exhibition, New Portraits, at the Edwynn Houk Gallery in Midtown New York, on view September 6 – October 1, 2022. All works courtesy Sebastiaan Bremer and Edwynn Houk Gallery NYC.

Interview by Devon Dikeou

Install Shot, New Portraits, September 2022, Edwynn Houk Gallery, photography by Fyodor Shiryaev

When I visited your studio once you were working on this series and as we were talking, you were working, so talking and working . . . And you had a turntable going. I can’t remember the song or LP but it was a wonderful moment of process intersect . . . Could you speak about that process and intersect? How you come up with the conceptual model, create the parameters, and then set about physically combining the two . . . What is the music that makes that happen . . .

My works take a very long time to make. As the drawing and painting on the photographic print takes shape, I slowly make tiny marks with ink while the outside world filters in. Weather and light make a strong impact on me as well, since my studio has a lot of natural light. I see the sun move through the sky all day. This is not ideal for working with photographs, especially glossy ones, but I love it. The news, tremors, moods and music all end up inside the drawing. I don’t plan this, it happens to me. When I started working in this mode of combining photography with painting and drawing around 1999, this blending occurred organically, and I have embraced it wholeheartedly.

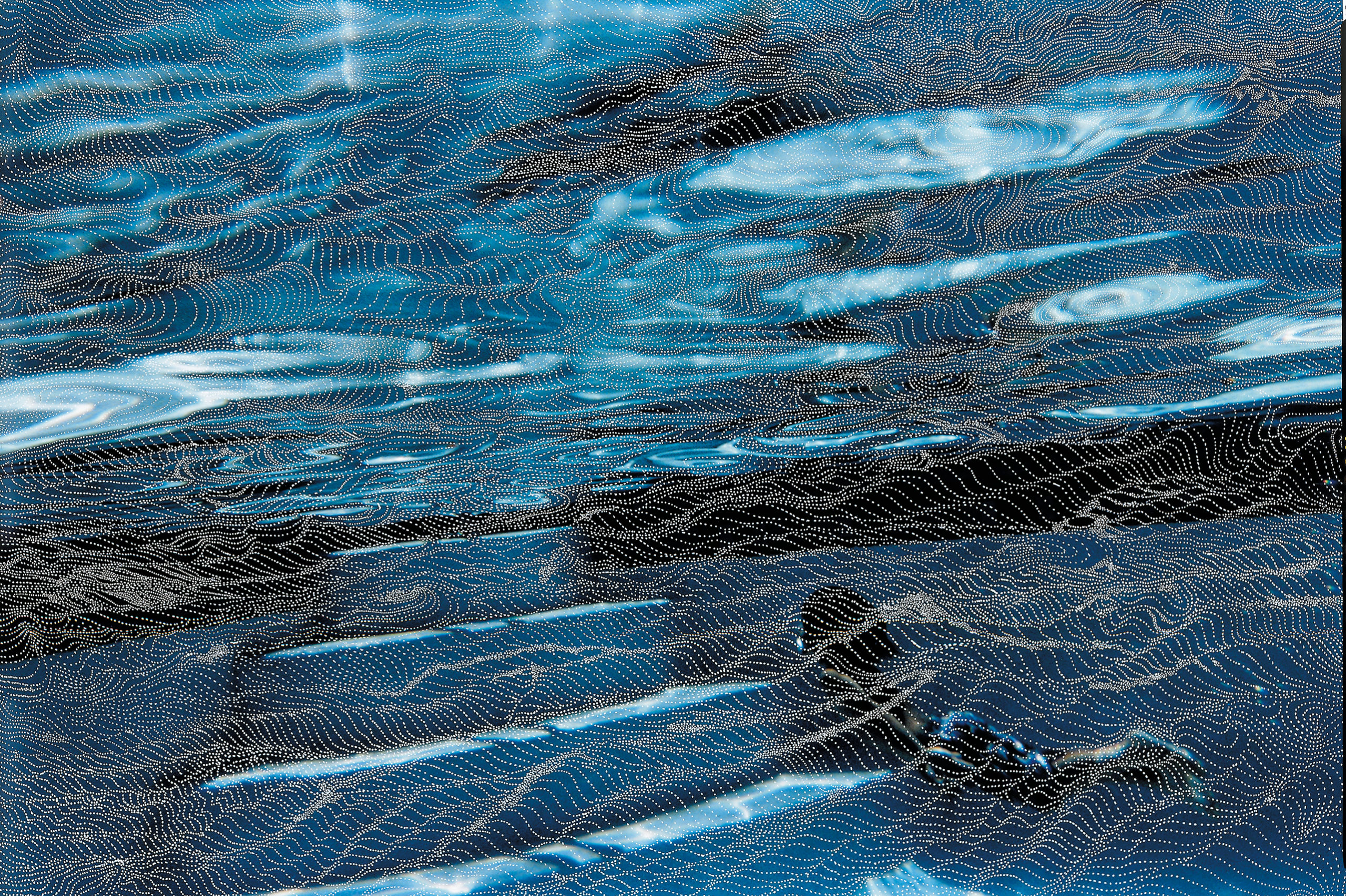

I Held My Breath for 13 Hours Afraid She Wouldn’t Come Home (Pool II), 2000, Unique hand-painted chromogenic print with mixed media, 40 x 60 inches

The idea I start with is morphed into another form and so on and so on. It is similar to bricklaying in that the first brick in a wall informs the position of the next. In music the chord progressions and sequences of notes or beats eventually take shape and form a structure. It can be very surprising to see what appears. Of course, I do set parameters and have certain goals on the outset, but I am open to accidents and surprises. This makes it exciting and confusing at times. There is a parallel to the recollection of dreams: you must have created them but did not control the story somehow. I sometimes have a playlist to set a mood or form an idea—and then I record it within my mark making subliminally and literally. The music of Miles Davis I play often, and the Band of Gypsys album by Jimi Hendrix is excellent for rocking me out of a rut. There are also periods where I work in quiet, or listen to podcasts. When I was a teenager I was always drawing, and when I was with friends I often drew while conversing—it was my thing. I still to this day enjoy talking on the phone or having people over while I work—this does not work all the time obviously—but I do like it. My practice is very solitary and I am a social person. To have visitors is wonderful sometimes—I work long hours and being alone can get a little much sometimes. Still, most of my work is made in solitude, with sound.

It seems to me too that in a way there’s very interesting things happening in this series, New Portraits, at Edwynn Houk Gallery, as they’re studio shots presumably and it takes a certain amount of commitment to a studio process—which creates an outcome in a medium dedicated to reproduction as part of the final outcome . . . And the images then are finished by your laborious individuated and unique treatment creating singular objects, which contradicts notions of photography as addressed by Walter Benjamin in The Work of Art in the Age of Mechanical Reproduction in a way . . . Thoughts. . .

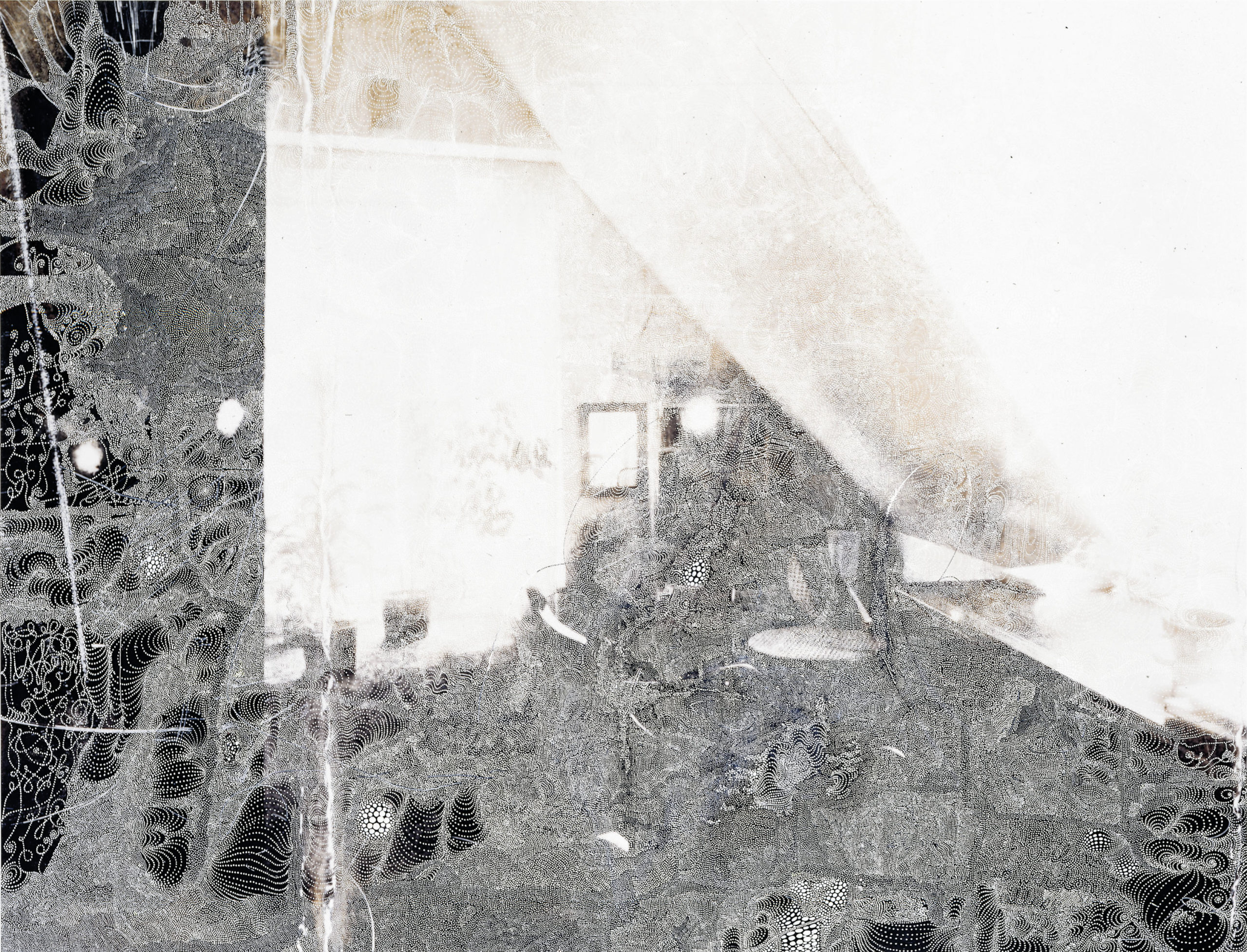

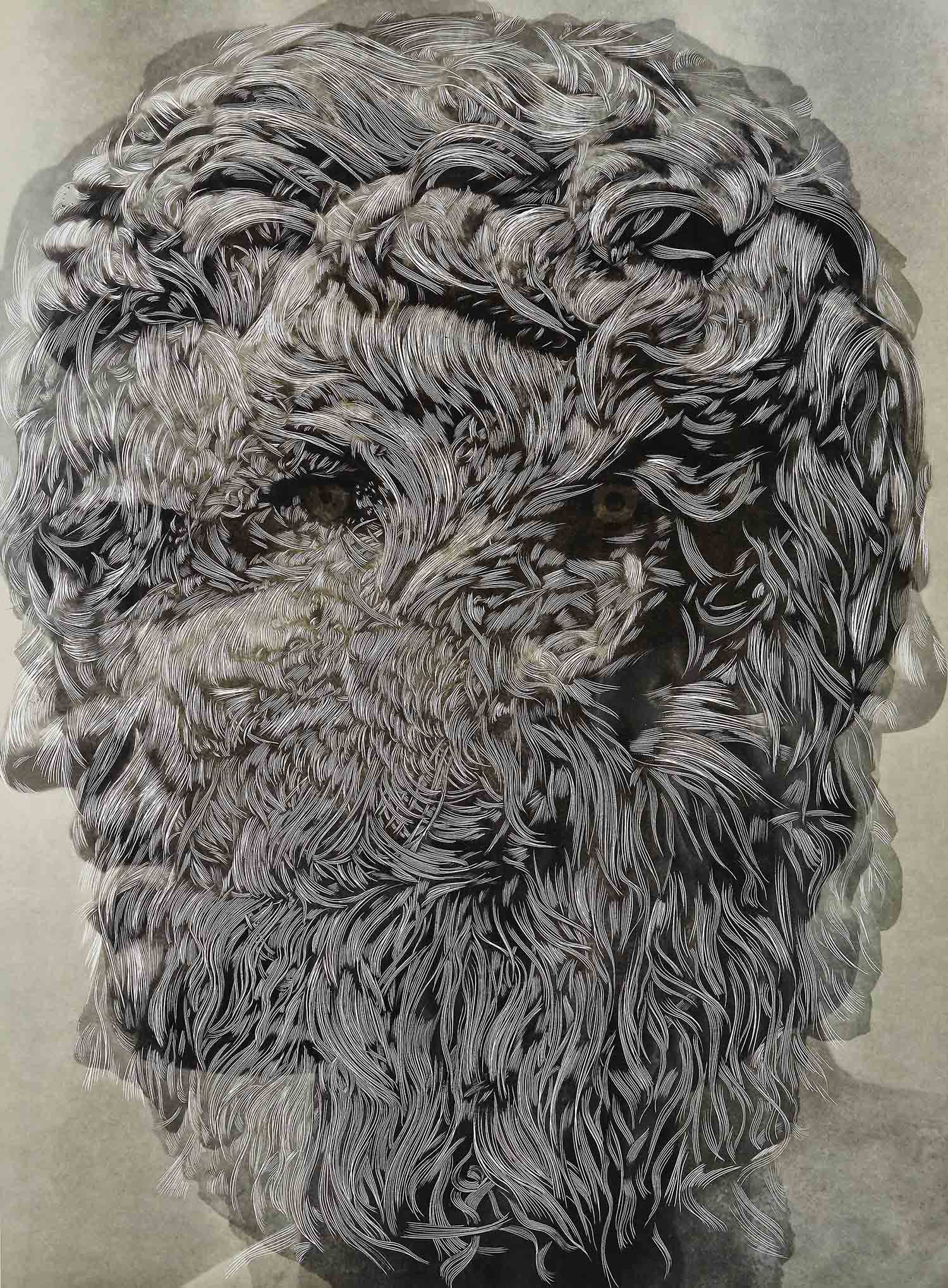

The sources for my works vary, as I am looking for different things to express in each individual work or series. Originally, I used a lot of photographs from my personal archive and transformed them with photo dyes and other means into some interior landscape on which I then worked with small white dots made with pen, paint and/or penknife. The dots became a solution to a problem I faced: I wanted my marks to be integrated, I wanted them to enter the reality of the depicted three-dimensional space of the photograph. By making small marks I felt I squeezed in between the little blobs of emulsion instead of creating a grid or linear filter encapsulating the photograph. Another advantage was that it slowed everything down, and gave me time to think and watch as the drawings took shape. Most of the photographs I worked on were shot by me, but not necessarily made with the intention of using them as works to draw on. Some photographic prints I worked with were quite old, and I had used some as sources for the paintings I made in the early 1990s. The stains, paint drops, creases and rips that I made by accident whilst using them in my studio I incorporated later. I photographed the small prints and printed them large. I also made a series where I used small faded black and white Polaroids. They were shots of the interior of a house I lived in with my family for a few years in the early 1980s. Who took these pictures I never found out, but I think they were made for use by the architect who worked on the house we lived in from 1978-1983.

Castle (I-Study), 2001, unique hand-painted chromogenic print with mixed media, 40 x 60 inches

I re-photographed these small black and white Polaroids with a large format camera and turned them into oversized prints on which I drew. These modes of working were dominant for a few years, until at some point I was intrigued by photographic prints without using any negative. By drawing on the dark or black prints I was able to create the illusion of a photograph, a practice which I continue to return to.

I have also made a series or works using pen-knives, making marks by cutting and removing parts of the emulsion, again interfering with the underlying image and the material of the paper, creating a completely different reality and turning the photo into an object of sorts. This was also the only series where I used photoshop, in the crudest way in order to layer images. I am bad with technology and dislike working with a screen and computer. In none of my works besides that series is there any photoshopping. With a computer the possibilities are endless, and the choices overwhelm me.

I much prefer not being able to correct or step backwards and I make all the manipulations of the print with pen, acrylic paints, rips, scratches, inks and dyes.

The physical object, the photographic print with all its different surfaces and sometimes marks of wear and tear are what I love. It is another recording of time in a way. Blemishes are fine, and I have even found that the most beautiful photograph is the hardest to work on. There is little to improve. The joy of squeezing out a meaningful image by manipulating a not-so-spectacularly beautiful print by hand is wonderful.

In most works the print functions as a fully charged battery brimming with content and energy underneath the worlds I build. However, they are not the dominant factor. The image is secondary, the preciousness or meaning I sense in a photo is in some cases the foundation and the combination of my work and the underlying image create an interwoven structure.

Photographs are made for reproduction. A negative can be reprinted over and over, and the surface of a photographic print should not be messed with for archival reasons.

I practice the opposite of that. My works are paintings, in the sense that there is only one work after I am done working with the piece. Any kind of reproduction of my art is just a facsimile, since the texture of the surface and the contrast of the matte inks on the glossy surfaces in most of my works is not reproducible in any true or faithful way. Each artwork of mine is unique, and reproductions fail to capture the surface of the object I create. I do everything anathema to traditional photographic practice and I think I have a relatively unusual relationship with photography. My work lands somewhere between painting, drawing and photography. There is even in some cases a sculptural quality to them, since the surface is very much an active part of the piece. The paint drops I apply become almost like braille, and the light sparkles off the smooth surface of the acrylic. The cuts I make with X-acto knife create ridges that are clearly visible and protrude the surface, and in some cases I removed the layer with the emulsion from C-prints, exposing the white paper underneath.

Glaucon, 2014, unique hand carved chromogenic print, 50 x 36.5 inches