Carlos Fresquez, Alley Freshener, 2018. Photo: Third Dune Productions. Image courtesy of the Downtown Denver Partnership and Black Cube.

Black Cube Nomadic Museum is a non-profit experimental art museum based in Denver, Colorado, that supports artists’ projects occurring outside traditional exhibition spaces. Their current exhibition, Between Us: The Downtown Denver Alleyway Project, partners with Downtown Denver Partnership and Downtown Denver Business Improvement District to transform alleyways in the downtown Denver area with installations by five artists curated by Black Cube: Carlos Fresquez’s Alley Freshener, Kelley Monico’s Alley Cats, Stuart Semple’s I should be crying but I just can’t let it show, Joel Swanson’s Y/OURS, and Frankie Toan’s Public Body. Each installation was created for its specific site and delivers its own meaning and context. Earlier this month Black Cube’s Executive Director and Chief Curator Cortney Lane Stell took me on a walking tour on a sunny Denver day . . .

Interview by Brandon Johnson

This group of installations are situated within alleys in downtown Denver. How was the idea to position artwork in alleys conceived? Were there any historical precedents for this type of site that you’re aware of?

The idea started by an opportunity that a friend, Castle Searcy, was working on. She had proposed a mural project to the Downtown Denver Partnership, the nonprofit organization that activates Denver’s 16th Street Mall. Her proposal was to commission muralists to create “3d murals” of Colorado’s attractions and pitched them as selfie opportunities. At the same time, Castle and I were involved in another project. She raised the opportunity to have Black Cube curate the project. I felt that with the funding and interesting sites, we could do something more engaging and dynamic than murals . . . (Denver has been in a major mural Renaissance lately). That’s basically how we got started, practically speaking.

In regards to your question about historical president, I am not aware of a specific history in fine art . . . but I do know the spaces have a long history with graffiti and mural art. Denver and other cities have seen a lot of growth in this area since the ‘80s, as it has become a tool for developers and real estate owners to add a youthful funk, at a relatively affordable price tag.

How was this group of artists chosen? Did individuals submit proposals or were artists invited to create site specific works?

The intent was to mostly focus on a local artists approach. As the curator, we selected the artists and, after a studio visit, invited them to come up with a few ideas we could explore together.

The 16th Street Mall is known as a major tourist thoroughfare in Denver. During our walkthrough we encountered a family from Tennessee admiring Kelly Monico’s Alley Cats installation. How did the expected audience factor into what artists and works were chosen?

I approached the project looking for works that would be accessible to a wide audience, from those within the field of contemporary art and to passersby. Many of the works are intended to draw people in. I did this by selecting artworks that could be recognizable at first glance and also elicit a candid response such as amusement or surprise. My hope is that this method encourages viewers to think more deeply about the works in relation to public space. However, I am not sure if that is happening outside of the art community.

The public reaction to Kelly Monico’s Alley Cats installation has been very interesting to experience. Cat-lovers are literally coming out of surrounding offices and businesses to comment or ask questions. Families also love to hunt for all of the 300+ cat tchotchkes—it’s almost become a game. This installation has really shown me how wonderful it is to make public space a place for curiosity. Though, I have to say, I’m not sure that people are thinking about the work more deeply. I have yet to hear anyone question the line the artist is walking by calling attention to our desire to anthropomorphize cats by turning them into doe-eyed garden sculptures or the reference to an infestation. Another work that has garnered a lot of attention is Carlos Fresquez’s large-scale tree freshener sculpture that dangles above a line of dumpsters in a particularly pungent alley. The work regularly makes passersby laugh, but it also speaks to a deeper level as to how we care for the city and the ways we perceive alleys as dark, often overlooked, public spaces. I also love the art historical connection to other provocative public works such as Paul McCarthy’s inflatable sculpture, Tree, which references an anal plug.

Exhibition tour led by the Montbello Drumline. Photo: From the Hip Photography. Image courtesy of the Downtown Denver Partnership and Black Cube.

Interesting to hear that you feel the general populace may not be engaging with the work on a deeper level. What leads you to draw this conclusion? Contemporary art often relies on explanation to reveal its meaning, and there are placards on site to assist viewers with accessing the artists’ thought processes . . .

I have to say, though, that I don’t expect everyone to have a deep contemplative experience. It’s perfectly fine for people to not even see these interventions as artworks. For me the priority is to disrupt space, challenge the mural statuesque, and offer artists unique opportunities that are both supportive and challenging. With that said, the most common response I have seen with these works is watching people stop to snap a photo, then move on. From that I’ve inferred that most people are simply amused by the image, but that is a huge assumption. Some folks do pause to read the text panels, but it’s far more rare (maybe 1 in 30 people). I guess all of this is the beauty and challenge of showing “art in the wild” so to say. I should also mention that expecting some would desire more interaction (mostly the artists and locals who follow Black Cube), we programmed tours and artist talks. The first tour was super fun—it was led by the Montbello drumline—it felt more like a parade . . . we had such high attendance that we had to use a bullhorn to talk at each alley!

Given the challenge of competing with the constant information flow and demand for attention from smart phones, I’d say that someone even stopping to take a photo means something. You never know how that image sinks in or resurfaces in their mind. But the drumline-led tour seems like a great idea and successful in deepening the engagement level. Any other programming for this project and/or other upcoming Black Cube projects that people can look out for?

There are no further programs scheduled for this particular project at the moment, but the works will be on view through (at least) May of 2019. However, we have several other projects in the works. The next project to open will be in Mexico, during the first quarter of 2019 with Alejandro Almanza Pereda. He has been amazing to work with— a lot of his work tests the limits of materials (both physical and/or perceptional). We are currently exploring a few of his ideas, so it’s a little early for me to speak on the details of the project. The best way to keep up on all things Black Cube related is by signing up for our mailing list on our website blackcube.art.

Installation shot, courtesy of Gildar Gallery

A Harmless Exercise in Boundlessness . . . (or So Far I Haven’t Killed Myself or Killed Any Other Person) an exhibition at Gildar Gallery in Denver featuring the work of Andrew Cannon, Jasmine Little, and Emily Ludwig Shaffer uses the foil of mushroom foraging as its frame. An increasingly popular American pastime that would normally find little to do with contemporary visual art betrays its avant-garde history in the activities of John Cage, mushroom lover and reincarnator of the New York Mycological Society. At this crossroads of mycology and music theory, the idea of “chance” relates a multiplicity of meanings and purposes, from the I Ching to stumbling upon a flush of maitake in the woods. In a similar way, the work in this show revolves around this intellectual framework, with the work itself taking many forms including painting, sculpture, and multi-media assemblage.

Interview by Brandon Johnson

The exhibition’s title is sourced from quotes by and about John Cage. Mushroom hunting involves identifying the conditions needed for one to be at the right place at the right time in order to find a bounty. How do you feel that your work does or does not engage with chance? And as an artist, do you ever feel that it’s necessary to set the table for ideas or a vision of new work to arrive?

AC: I don’t think about chance really—or at least not in the emphasized sense that Cage did. In terms of setting the table, I try to just work and walk as much as possible. Stay in the right place long enough—the broken clock is right twice a day or whatever. It’s less elegant than only showing up when it’s productive, but it always works eventually. I go through a few miles of forest when I walk to my studio and see fungi or don’t, and I work in my studio and make progress or don’t.

JL: Yes, I think my work involves chance, but maybe more in the sense Andrew described. It is always a surprise when something comes about in the studio—that makes painting very fun and exciting for me. And I spend lots of time trying to make all the conditions right in the studio for something to occur, but I consider this sort of cleaning, organizing, standing around, etc. as studio time even when the end result is not known. I don’t really plan my paintings, or actually, I make lots of plans for paintings and don’t really follow them. Something typically occurs in the process that seems important or more interesting than the intention I set out with, so I allow that to become primary. I have to put forth a lot of effort and intentionality in mushroom hunting too—the best conditions to find what I am typically looking for are kind of distant from my studio, but this also does not manifest in the intended manner. It’s just the starting point and creates the space required for the event to play out however it happens to.

ELS: I generally agree with the old saying that chance favors a prepared mind, but like Jasmine and Andrew, I don’t actively think about chance that much when I’m making work right now. I did a lot in the past, though, and a big part of art-making for me has been developing tools and parameters in my studio that allow space for the ideas that interest me to emerge in an organic way.

The consumption of wild mushrooms involves risk—of gastric distress at a minimum, and death at the most drastic. What types of risk arise for you as an artist?

ELS: I have a lot of messy feelings and thoughts about the term “risk.” In short, though, I think some artists make powerful artwork that overtly engages risk, but it’s usually by exposing threats that they or others already live with on a daily basis. Actively creating risk is an idea I more often associate with male hubris. So far, my relationship to making art is very different from artists whose work has literally killed themselves or others—even if by accident. I think anyone who puts their own time, body, emotions, effort, and resources into any endeavor is risking something, but it’s a term I feel uncomfortable or uninterested in claiming as a key ingredient in my process.

JL: I agree with Em regarding the messiness of the term “risk.” When I was younger I really liked to gamble. Lately though, I feel like I have spent a lot of time and energy to create a safe environment in which I can make work.

AC: I’ve only poisoned myself once—I had a bad reaction to some imported aspen boletes I bought frozen from a Russian grocery store. I do eat a lot of mushrooms but only occasionally is there any lingering doubt I’ve misidentified what I’ve collected though, and if there is, it adds the smallest bit of friction to an otherwise quiet hobby. Emily is right and I agree my work does not engage in any serious or mortal risks, but I think hopefully there’s always a feeling you might embarrass yourself or the real fear you’ve financially overextended yourself.

In this show, each of your work engages with natural forms or the idea of nature—including mushrooms themselves—abstractly, representationally, and/or literally. What does the environment mean to your practice?

JL: I have always had a strong relationship with the environment, I grew up camping, rock hunting, spending time outside. My parents were both really good at identifying plants, minerals, rocks, and spent time describing the landscape and knew a lot of narrative history associated with different places. I really wasn’t terribly interested as a child in rock hunting in Death Valley in the summer, but I appreciate that I had that type of upbringing now. Where I currently live is a really rural community in Southern Colorado and I spent a lot of time hiking and being alone in nature. I am interested in this type of activity as an experiential thing. My paintings in this show are influenced by the season and depict the plants that were out right then such as berries and mushrooms. And they also depict things you find on the forest floor like skulls and branches. The work was influenced by Dutch still-lifes, illuminated manuscripts, pattern, decoration, etc.

I was also really obsessed with smoking when I made these paintings, and my teeth, I was having all these dental problems. Anyways, I was quitting smoking so there is like this literal deterioration of my body going on, how that feels, etc. I think this sort of obsession with my physical body and death is really present in the work. And the way I paint and sculpt is always very physical, bodily. One of my favorite ceramics in the show sunk into its current mushroom-like shape naturally from being built to quickly so there is also this very literal, natural aspect that is material in my work.

ELS: When I invoke natural forms, I’m pulling from a lot of traditions like landscape and still-life paintings, but also working within common metaphors: leaves can be fingers, legs, vulvae, phalluses; potted plants are domestication, cultivation, artifice. Most of what I’m painting now is from my imagination, so when I paint plants they’re usually stiff or plasticy and end up more like an idea or the fantasy of a plant rather than something that is observed and actually living. The garden and the greenhouse are also potent spaces for me. These feel daunting because of the amount of control and care they require, but I also see them as tender, as an exercise in nurturing or cultivating a craft and aesthetics. I think gardening/plant keeping traditions express a lot about a person or a culture, and I sometimes think about them as symbolic of desires for some prelapsarian utopia.

AC: I’d just say “yes” since my thinking about nature isn’t particularly organized and the question is too sprawling. I think a lot about nature and the image of nature, how flora get woven and encoded into culture. But I also think about painting, and fireplaces, and airplanes. I’ll look at mushrooms in Central Park and then walk into The Met and look at lacquer boxes and I try to think about it as one continuous system. One afternoon feeling.

Mushroom hunting calls to mind pastoral utopia. Does your work engage in the utopian?

AC: It doesn’t, or at least I don’t throw that word around much. I do like the utopian novel. News from Nowhere, Herland, etc. I had a professor that would say every artwork is, for better or worse, a vision of the artist’s perfect world. That makes sense to me. I try to keep each work self-contained, its own trial world.

ELS: My mom was an architect so I grew up running around architecture firms, flipping through all the modernist starchitect coffee table books, and seeing architecture periodicals every month. I was obsessed with the different ways the architects and designers would add people, plants, and dappled light to their drawings and models for buildings yet-to-be-made. I thought they were both beautiful and creepy. These scenes were supposed to be utopian and inspire the imagination, but they were mostly stiff, unnatural, and read like a faulty promise. I don’t always think about the spaces in my paintings along these terms, but I’ve definitely explored it in some—especially from a little over a year ago when my old studio had a huge Renzo Piano building being erected outside of it.

JL: I don’t think my work is overtly concerned with utopian ideas. There is conflict, tension, and the materiality of the paint is pretty present. I have always been sort of an immediate painter and have a hard time with illusion. I think there is something utopic philosophically in my work. I am contented with a lot of different types of “successes” in individual works, like how Andrew reference earlier embarrassing yourself in the work—that is defiantly something I enjoy. I am not afraid to make something bad. Basically, I think being able to paint full-time is a crazy luxury, sort of an utopic dreamlife and political act in itself.

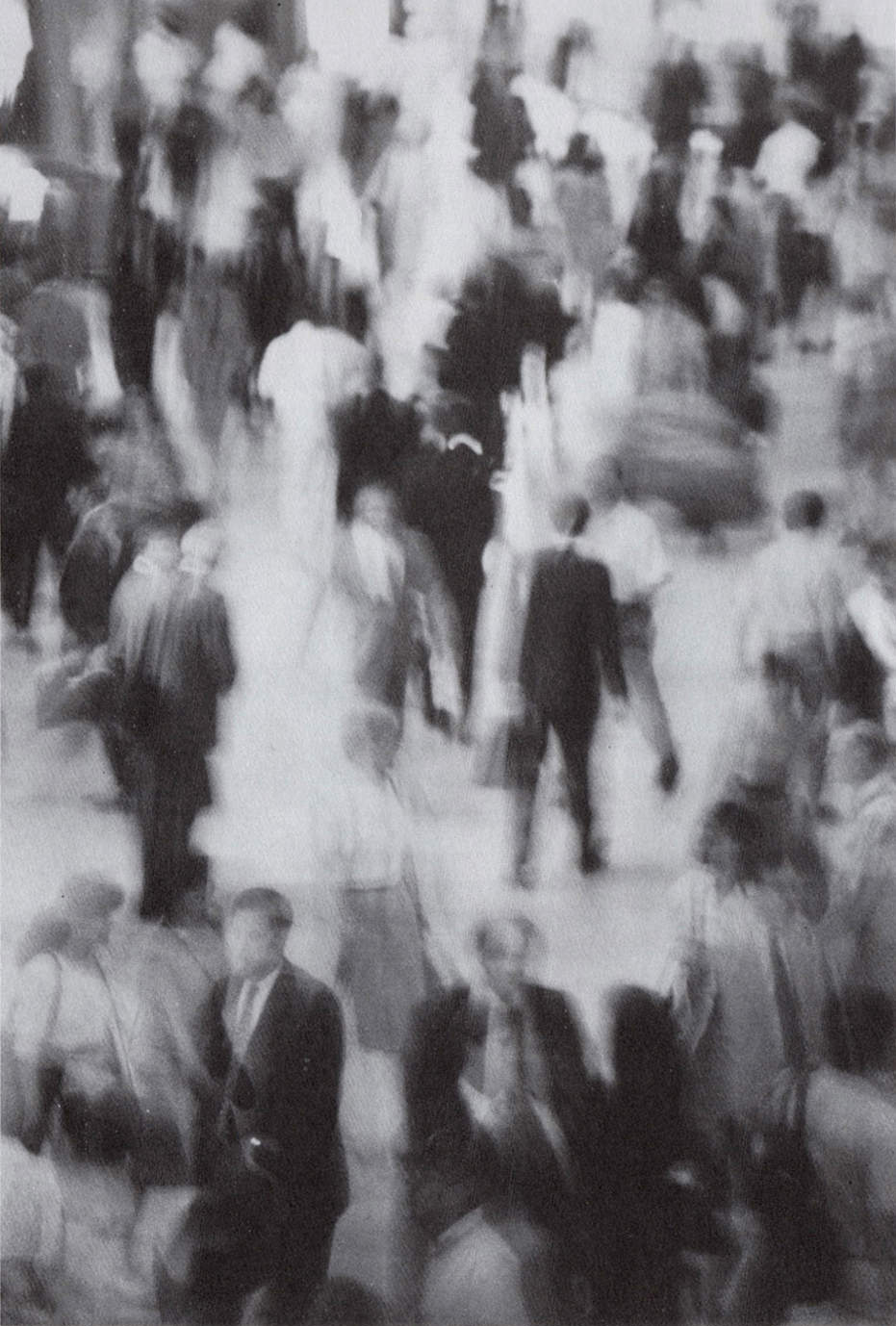

Devon Dikeou, Rush Hour, Grand Central Station, black and white photograph, 1988

Devon Dikeou’s second solo presentation at James Fuentes, “Here Is New York (E.B. White)” features what are among her earliest artworks made as a young artist in New York City. There are two security gates paired with other security-oriented materials—glass blocks and acrylic sheeting—and an enclosed kiosk, all of which one would regularly find on the streets of New York (depending on the hour). These works set a seminal precedent exploring spaces and objects of transition, which would later find other forms and subjects as her career progressed. So with this exhibition we return to the root of things, to revisit where it all started got Devon and an era of heavy analog materiality that is changing with the sleekness of this post-digital era. “Here is New York (E.B. White)” is on view September 8th – October 7th, 2018.

Interview by Brandon Johnson

These security gates represent to you the “in-between.” Other works of yours also engage in this realm. What is it about the “in-between” that appeals to you?

John Baldessari said, “Instead of looking at things, look between things.” I ran across this quote only in the last year, which was in a book of collected quotes by artists under the table of contents’ moniker of “Advice.” And it made a lot of sense to me. Many of the series in my practice touch on this “in-between.” The curtain behind the comedian, the flower that accompanies the big picture, the chair that seats the Pope, the minimalist donation box soliciting funding, the plant in the mall that is between decoration and commerce, the jazz musician (like they often are) forgotten, the directory board announcing the exhibition. I’m interested in those spaces that are shared by all those transactional viewing experiences . . . the viewer, the artists, the gallerist, the critic. And more. What they all signify is something that I’ve always reflected on, and done and it comes down to this, which is very similar to the Baldessari directive. Look at the space between the leaves of tree, not the leaves themselves.

The show is titled “Here Is New York (E.B. White)”. You often use literary references to support and deepen your conceptual installations, adding a dimension of the human condition to cerebral artworks. In this instance, a quote from E.B. White. What do these titles mean to you?

There is this great bookstore called Three Lives in the Village near an apartment on Christopher where I once lived. It was and is spectacularly curated so to speak, and I maybe learned something about curating from that bookstore. It is tiny, not like the Strand—which is all inclusive, and where you can go for miles and days browsing. Three Lives had to strategically choose what to shelve, much less select or highlight. I’ve found some of my most beloved and cherished tomes there directed by the Three Lives curation, one being the slight thin paperback booklet that can be read in an hour called, Here is New York. It’s by E.B. White, who I only knew from Some Pig! and Charlotte’s Web fame. I quickly absorbed his adult message—and learned of his great, underrated legacy as a non-fiction writer—and re-examined the childhood tales I so loved. What is Charlotte, a spider, who weaves a web. What is New York, a web us flies have to navigate.

Security gates have come to represent a low-key quintessential part of New York street life. How else does this show find its groove in the Big Apple?

When I came to New York, it felt like a world of possibility. But it was equally dangerous as was it was joyful. Lots of artists have explored this, from Nan Goldin to the Ramones, Blondie to Robert Mapplethorpe. They had all the stages covered, so I worked on the background . . . The gates were as ubiquitous then as they are now, but a universal signifier of urban environments worldwide. The gates seemed like the perfect segue.

The industrial nature of the gates is representative of an engagement with functional ready-made materials positioned within a conceptual framework that characterizes some of your early works. What was the draw of these materials and subjects for you at the time?

New York. Of course, that was the platform, and I’ve been discussing this with Cortney . . . The difference between platform and medium . . . But I think the gates are the medium. And nothing can be done without Duchamp. So those gates are the Duchampian gesture/medium in and on the platform of New York.

Being some of your first works made as an artist in New York, what does it mean to show this work in a contemporary context—over 25 years after they first premiered?

I remember going to an exhibition at the Whitney (Breuer Building) in the ‘80s of Vija Celmins and Dan Graham. I just loved it. The wall texts kept touting a phrase which I thought odd at the time . . . “An Artist’s Artist.” I thought it was a slight in a way, because the work was incredible, those dense drawings of oceans, surface images of housing—both reflecting something immeasurable, and perfectly and specifically dated. Now these artists are larger than life as they should be, I would only be so happy to be called an artist’s artist even if it’s 25 years or more, later.

Finally, in revisiting older works, can you see any ways in which your work has changed? And ways in which it has stayed the same?

I am an archivist by nature, save everything, never know when you’re gonna need it . . . All things everything, a page from Warhol. But funnily enough, the gate works physically disappeared. Gone, and yet always felt like that friend you see again and pick up with as if no time has passed . . . Or a time capsule you open and greet with abandon. I’d look at the photos of the gates and long for the youth and early conviction of that other time. So it’s nice, a lovely present to see them again, to visit with these old friends, and see what as a young person and thinker I was aiming for and then as a more mature artist now, how I picked up those threads . . . And the ability to make a relation “between” them, there we go again. And so their being made again, these gates, makes me smile. Archive that, Devon.

Kenny Schachter, Kenny Mostquito, 2016, Digital c-print on plexiglas, 10 x 6.5 in

Kenny Schachter, art world bad-boy, bares it all in his deep-diving retrospective exhibition at Rental Gallery in East Hampton, on view through October 31st, 2018. We catch up with Kenny via text to discuss the big show, what led up to this moment, and what is to follow . . .

Interview by Devon Dikeou

You started curating in the late ‘80s, early ‘90s . . . I particularly remember the German show and stuff in your 1st Avenue flat. But also stuff at BACA Downtown, above 303 in the vacant Massimo Audiello Gallery on Greene St. And despite your Eulogy . . . the shows were amazing, not “a mess,” giving so many artists the platform to show at a time when there were so few. Give us the “best of” of those early shows . . .

My second show, “Decorous Beliefs,” highlighted the worst attributes of humans: racist, sexist, and generally prejudicial behavior. You serving up blood-rare sandwiches to be devoured by the derelicts of the early ‘90s emerging art scene we called friends. Then I clocked Roberta Smith in the space one day and couldn’t believe my luck—to this day I am enamored of every word from her keyboard. When I approached her and began explaining the intent of my show, she reprimanded me in no uncertain terms without expressing an emotion: “If I needed art explained to me, I’d never leave my house.” Ouch. I’ll admit to a few tears when she departed.

Talk about the segue from younger artists to mid-career or older artists and the importance of working with some of the major architectural thinkers of our time.

For a good long time, say close to ten years, I couldn’t tolerate a conversation with an emerging artist. I felt they were literally sucking the breath out of my mouth; then, so emboldened and strengthened, they’d walk all over me. No joy. So first I launched personal and professional relationships with Vito Acconci and Zaha Hadid; I am in awe of talented, brilliant people and was, like a fan, simply in thrall of their company and accomplishments. Not to mention I commissioned many projects and did countless curatorial and writing projects dedicated to both. I thought maybe some of the stardust might be catching. After getting soul-sucked by young artists for decades, then as an acolyte of the greats, I needed money and began secondary dealing. I was a bad lawyer, a bad tie salesman, and a worse art dealer.

Who are your mentors . . . Who are your enemies ; )

My mentors or rather the people that inspired me (I didn’t get much help from anyone) are Vito Acconci, Zaha, Paul Thek, who was an example of the notion that sometimes, being too good is too bad—he was a brilliant master of many media but was simply too far ahead of his time and lived too much of the time abroad and lost support after an early career spurt. He failed miserably in life and work, only to be celebrated in death with retros at the Whitney and Reina Sofia (I advised on both and wrote regularly on his work). My enemies are anyone hypocritical, not forthright or transparent. I’m often contradicting myself so sometimes I can’t stand myself either.

Speak about the relationship you have with your work to the market—be it visual, critical, or otherwise . . .

I love the market. Sure it could be ruthless, hideous, disingenuous, reductive . . . but really those characteristics apply to the players. Art and money have been sexing it up for centuries, from Durer to Rembrandt to the private plane flying the handful of today’s artrepreneurs. I don’t care—I need art and I need money to make and pursue it. My writing chronicles the misfits and general commercial activity at fairs and auctions so it gives depth and meaning beyond just recording sales. I am after the behavioral dynamic of social, political, and economic interaction as it applies to art. When it comes to selling my own work, I am a nervous insecure wreck and run from the dialogue.

What’s the thing that surprised you about playing all these roles in the art world and how it affected all these roles, in terms of practice in general, and the retro?

I stuck to it for thirty years. It’s a miracle I never compromised and that I even have an audience. I am so humbled and surprised I can’t believe anyone reads me or looks at other stuff I’ve been up to. I always thought I was kind of unlucky, stuck in the margins, and though by nature I will always be located outside the norm somewhere, I just can’t believe how things have gone in the past five years. Now I’m an old emerging artist that is selling. At a small gallery when they are said to be under siege. I am pinching myself now.

You were involved from the beginning of zingmagazine . . . And have done two books with us . . . How do you go about doing a retro or exhibition vs a printed project?

For me it’s all an organic mush. It just comes out of me and I don’t differentiate from any of my pursuits, be they as far afield as selling a Picasso and making a video or curating my kids into shows and supporting their work. I have a very democratic outlook on life and relish that I’ve never had a repeating day in my life. Though sometimes I feel like I’m merely treading water and stuck in the film Groundhog Day. I must say of all the disparate things I’ve done, having this art show transformed my life, for the first time I almost think of myself a real artist. Scary—for me and you.

Basically, how did you get a show at Rental and what made you want it to reflect the idea of a retrospective . . . in terms of you as a curator, gallerist, artist, collector, dealer, critic, writer, person extraordinaire of the ’90s art scene. How much is real how much fiction?

No fake news here, what you get is what you get: me stripped bare, naked, humiliated, walking down main street with strangers looking at my . . . oh never mind. Making art so publicly for the first time in more than 15 years has been an extraordinary experience. I can’t even recall how Joel Mesler and I met a few years ago, but he is a younger version of me, namely a jack of all (art) trades—making, curating, dealing and gallery-ing. He’s hilarious, supportive, talented and fun, as an anti-religionist, it’s not an easy to mouth, but I’ve been blessed.

What’s on deck?

Family Guy, the fourth installment of exhibits I’ve curated incorporating my family (though I mostly can’t stand any of them), and works we’ve all lived with for decades, at Simon Lee Gallery in London, then another one-person show in LA in Feb at Niels Kantor during Frieze/Felix art fairs in town and then . . . more of the same. I can’t temper my crazy love and passion for looking at, thinking about, and writing on art. And now, I am afraid to disclose, making it seems to be the next area to apply myself even further. I just can’t help myself baring it and sharing it. Sorry folks!

Devon Dikeou “Tricia Nixon: Summer of 1973” installation view

Cortney Lane Stell is Executive Director and Chief Curator of Black Cube, a nomadic contemporary art museum based in Denver, Colorado. Michal Novotny is Director and Curator of FUTURA Center for Contemporary Art in Prague, Czech Republic. In their first collaboration, these two organizations have partnered to host Black Cube fellow Devon Dikeou as a FUTURA artist-in-residence in Prague. This resulting exhibition, “Tricia Nixon: Summer of 1973” is on view at FUTURA through September 16, 2018, alongside concurrent exhibitions by Andrew Norman Wilson and Lenka Vitkovka.

Interview by Brandon Johnson

In collaborating to produce Devon Dikeou’s “Tricia Nixon: Summer of 1973”, each of you are coming from very different cultural and historical backgrounds. How do you see an exhibition focusing on late 20th-century American politics relating to its context of Prague, Czech Republic?

C: The collaboration is simple—it focuses on an exchange between two countries, two nationalities, two artists, and two curators. Part of the vision of the exchange is to create conversation and share in the act of giving one thing and receiving another. So, this exhibition is part of that larger project.

In relation to the exhibition, for me it is mostly about memory—Devon’s childhood recollection of two concurrent news stories . . . a gas crisis and another about Nixon’s daughter keeping a fire and air conditioner on in the White House during this time. For me, seeing the architecture in Prague oozes with historical memory, ranging from Baroque and Renaissance architecture to more contemporary additions coming from the country’s Communist era.

This sense of the haunting of the past is very present in my experience of Prague and also these artworks. It reminds me of a text-based artwork by Anthony Discenza who produced parking signs that said “this is about something that happened a long time ago that continues to affect us today.” In many ways, I think these works also touch on ongoing global, social, and political issues.

Though the stories that Devon culled together are rather obscure—especially for a Czech audience—the air in the exhibition space is opulent (literally warm and cool). This thread roves through the exhibition and gently teases out concepts of ecological challenges, service, and personal comfort—all of which are concerns that traverse national borders.

Michal, I wonder how you read all of this . . . do you catch the same drift? Does the exhibition feel American to you?

M: It feels very American. But, if not the world, at least the society I live in, has been culturally colonized by the USA, so it doesn’t feel incomprehensible. Also, American politics is very present here in the media, maybe even over-present, at least what comes to the real material, economical, locally-political impact, so for me the parallels with the current US political situation are somehow explicit. Maybe even more than they really are there.

However, I do consider the program locally, and what is important for me is that Devon’s exhibition presents something artistically familiar but also uncanny. We have a long history of conceptual art, it is still the dominant discourse, but this exhibition shows something a bit different. Maybe it’s the unnecessity to poeticize everything, there is something a bit more raw in the situation encountered. Even if it may seem narrative, it’s ultimately not-so-narrative.

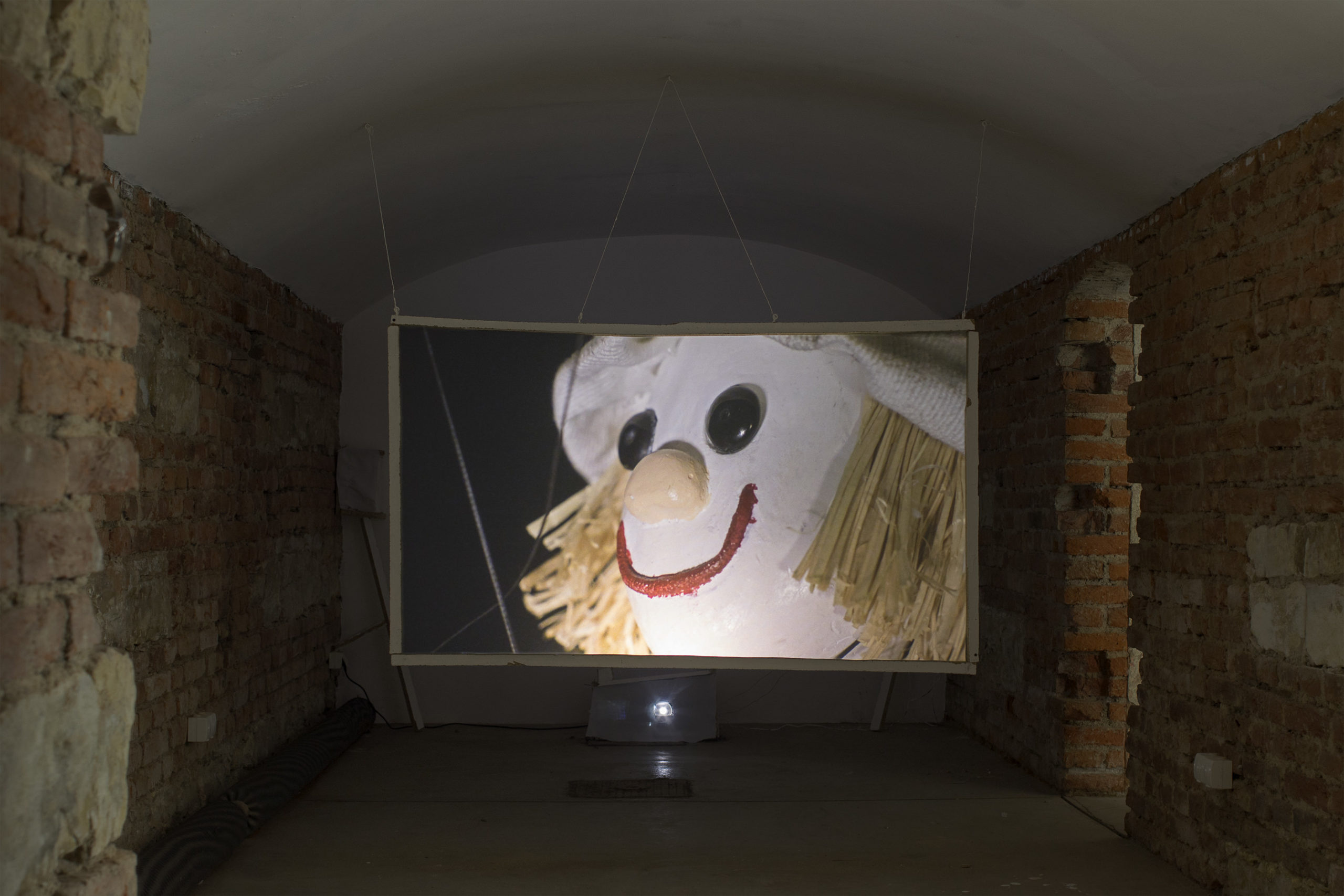

Andrew Norman Wilson “Andrew Norman Wilson” installation view

Going a step further, how do you see “Tricia Nixon: Summer of 1973” interacting (nor not) with the other two concurrent exhibitions at Futura, Andrew Norman Wilson: Andrew Norman Wilson and Lenka Vitkova: Slope? Michal, is there an attempt by Futura to consider in advance how the artists/curators will align, or is this occurrence more happenstance?

M: Of course there is. It is not by chance the two American artists whose solo exhibitions we open this year open also at the same time. On the other hand, the togetherness goes also in contrast, as we hope that if people do not like one exhibition they may like the other. So Lenka’s exhibition is on purpose unpolitical, meditative, intimate, and painterly.

Between Andrew and Devon I see a lot of structural meeting points even though the formal expression may be very different. For example, in the Ode to Seekers video the image of an oil tower merging into a mosquito head piercing human skin and the two remixed pop songs one saying “if it makes you happy, it can’t be that bad” second “I don’t care, I love it” makes a nice echo to Devon for me.

C: I see the three exhibitions in a more complimentary and contrasting way, rather than the connections between them. Given that the three exhibitions are on three floors, they sit like a layer cake in my head, or perhaps like an upside-down body. Lenka, who is on the top floor, being the feet or the earthly sensibility. Her paintings have a materiality to them and are quiet, gentile, and careful (and some paintings are literally feet). Devon, who is on the middle floor, is the exterior senses—stomach, ears, and skin. Her exhibition is rooted in physical sensations and the interconnection with the sociopolitical world around us. And Andrew’s work, which is in the space Michal calls the dungeon, is rather philosophical in tone, residing in the head and projections of the world. For me the three exhibitions are lovely in their contrasts. The differences in materials and relation to the viewer are quite different. I also agree with Michal that Andrew and Devon’s works have more links between them—they are both immersive installations that share a sense of angst.

M: Yes, Cortney that’s definitely a good metaphor, also, in a way, all three exhibitions are about belonging or alienated body . . .

How did FUTURA and Black Cube get involved in this organizational exchange, and what is the next step?

C: Well, Michal and I first met at a curatorial intensive for Independent Curators International in New York. We have stayed in touch since then, Michal has visited Denver and helped install an exhibition back in the day when I was the gallery director at the Rocky Mountain College of Art + Design. Since then, we have wanted to collaborate and this seemed to be the perfect moment to do so. Black Cube’s program allows for exchange to easily happen and Michal has been doing a lot of outside curating.

M: We meet seven years ago at curatorial program in New York sharing a certain healthy skepticism towards art world functioning and somehow a peripheric position. At that time we both hadn’t served the institutions we are at now, so maybe it turned out to be a good idea to decide to stay where we were.

Lenka Vitkova “Slope” installation view

Finally, Cortney can you speak to the current state of contemporary art in Denver and what you hope for in the future? And likewise, Michael can you speak to the same in Prague?

C: Denver’s contemporary art scene is rather small, we have one art museum and one contemporary art museum—these institutions seem rather stable and have very prominent education departments. Since the 1980s the city has had a sales tax that helps fund the larger nonprofits in the area . . . because of this we have a rather top-heavy nonprofit scene and are skimpy on most other areas of the ecosystem. This has created a super small commercial gallery scene, and even fewer artist-run spaces. My favorite part of the scene is the artists, there are some truly amazing people here . . . ranging from those that are embedded in the global contemporary art scene such as Devon to outsider artists that take use of the freedom of the West. But this is all changing as the city is going through a huge growth spurt; I imagine these changes will affect the scene in many ways, currently it seems like the biggest sign of this change is that a lot of artists are feeling the rising rent costs and consequently are moving outside of the downtown area or leaving Denver altogether.

M: Prague’s scene has changed entirely in the last 10-12 years and I dare to say FUTURA helped it. What used to be an entirely local scene operating via underground friend circle one-night event spaces is nowadays, along with Warsaw, the most developed scene in the former Eastern Block with maybe 40 subjects active in a city of 1.5 million. What I tried to create when I took over at FUTURA was a certain bridge for the international to come Prague but also for the Czech artist to get abroad. This slowly became more and more the export and also support to local artist. As the international presence becomes ordinary in Prague, we increasingly focus on supporting the local artists.

However, the scene has still one big problem and that is the absence of large functioning state institutions. There is still no museum of contemporary art in Prague and the sort of substitutes such as the National Gallery or the supposed to be Kunsthalle Rudolfinum do not replace this lack, and due to personal, political, and inner-logic reasoning, fail to be both locally and internationally respected institutions. This however also influences all the rest of an otherwise dynamic and developed commercial and non-profit scene. Artists in their 40s/50s/60s still exhibit in the alternative spaces, as there is no one to do them the proper catalog retrospective, commercial galleries have no sales to institutions, as institutions do not collect anything, and there are no coffee table books to show to collectors, as institutions do not publish anything. Non-profit spaces like FUTURA are competing in the style of low budget, often younger artist exhibitions, with museums that should be doing something else entirely on the hierarchy pyramid. On the other hand, all the scene, commercial galleries included, run on state support, which has maybe doubled over the last decade. It’s not easy securing funding—we are still only two full-time people working at FUTURA, running two venues, residency program, and doing 30 something exhibitions per year. While in most other European countries in the Western direction the state funding towards alternative art spaces is disappearing, in Czech Republic it grows every year. But I also think that in the end it is not a bad deal for the state and the taxpayers. The effectivity of labor is much higher in the small-scale operating spaces than in large institutions. The amount and quality of content we all create is definitely very cheap comparatively.