Rainer Ganahl and Devon Dikeou speak about Dikeou’s recent show “MTV Altarpiece” at Foyer-LA, an artist run space in Los Angeles, founded, operated, and curated by artist Connie Walsh. Concurrently running at The Dikeou Collection is Dikeou’s Retrospective, “Mid-Career Smear.” Both exhibitions are addressed. MTV Altarpiece closes July 31.

Interview by Rainer Ganahl

How do you feel showing one of your earliest pieces, made in 1986, for a third time? You also included it in your retrospective in Denver at the Dikeou Collection.

Showing the same work three times, MTV Altarpiece (1986 ongoing) and one image from Please (2011 ongoing) at Foyer-LA is not unusual and is part of my and many other artists practice and process, hence the “ongoing” cited in the dates in my titles. The ongoing process allows for reconsideration, re-examination . . . Originally, MTV Altarpiece was created for my thesis show at Brown and at that time MTV was at the nexus of its cultural influence . . . videos were no longer a visual illustration of a popular song featuring a band . . . The video WAS the song . . . This medium changed how music—an aural medium of music listening became a visual medium, one of watching, and how MTV profligated that change . . . And beyond musically. It was the cultural zeitgeist, the channel that caught and channeled literally how we consume culture—music and otherwise. MTV, the logo of certain period of time, was the sign, the symbol, the in-between platform representing music and all that comes with music as a visual metaphor. Now that sign, MTV, and that logo, that thing we think of associated with the letters, means different and other things, but still remains a sign, maybe even more of a sign. And the audiences have culturally shifted, and that recognition may land in the realm of nostalgia . . . It may land in the realm of MTV’s own cultural prescience.

Perhaps that is now why two different curators were so attracted to MTV . . . Cortney Lane Stell, the curator of my retrospective, Mid-Career Smear, at The Dikeou Collection, was insistent that MTV Altarpiece be recreated . . . So it was, and is displayed at The Dikeou Collection Pop-up. The Pop-up is in the old abandoned Jerry’s Record Shop on East Colfax . . . And Jerry’s was the epicenter of the Denver Music scene. Now it is a space which houses a collection of approximately 15,000 albums and is replete with all the trappings of the Jerry’s Record Shop scene, grunge, graffiti, vinyl . . . MTV fit in perfectly. Connie Walsh, an artist/curator happened to be in town and she visited MCS, keen on visiting both spaces (California and Colfax), despite her small pocket of time. In fact, I think she’s one of the few who saw both iterations of MCS at the time. Anyway, she has created a vibrant space in LA adjacent to her studio called Foyer-LA. Foyer, by definition is the room before, the room you enter, the segue that leads you in. As an exhibition space she gives that space a voice and gives the audience a preview . . . MTV found another lifeline in her space . . . So the three, 1st destroyed because it was held together with a glue gun, a tape gun, and staple gun, shown to a small audience in Providence in 1986, the second recreated for a thirty plus year career in Denver, the third a splash in Foyer-LA . . . And that last splash also includes a diminutive photo from my exhibition “Please”. . . A still life of a bouquet of flowers (Lilas et Roses, 2011 ongoing) after a series that Manet painted while dying of syphilis . . . A swan song . . . harkening back the heart of the altarpiece, the flowers in the MTV Altarpiece.

Since we are talking about your MTV Altarpiece, we must talk about the most effective distribution of music and the revolution music videos brought to people around the world. Do you think that the music got any better—we know for sure more people got richer?

I am not really much of a music anything so my reflections on it as an industry/critic won’t give much insight to anyone. The distribution probably worked like the radio . . . payola . . . But I am even less equipped to comment on that . . . I’d wanna “phone a friend” and that friend of a friend would be Sasha Frere-Jones. Beyond that, the reason I was so fascinated and still why the work holds resonance is because MTV has become more than a platform, it has become a sign . . . It is a world recognized brand like Nike, Coca-Cola, or . . . Apple. It changed our lives and how information is processed. MTV brought us more than just music . . . The first Reality TV program, The Real World, and the first death of an “Reality TV Actor” on The Real World of AIDS—the Young Vote became an important recognizable voting block leading to the Clinton Presidency, to name a few of MTV’s cultural implications . . . Whether MTV does so now is . . . Well their logo and award statue reached for the moon and literally the MTV logo has a space ship taking off as its electronic jingle pulses . . . Branson, Bezos, and Musk make good on that space bet . . .

What is your current taste in music (and why not include art in this question) and how do you think music and art and their distribution look in another 35 years?

Someone referred to a mountain radio station here in Colorado as the ’80s prom night station . . . Music does play a part necessarily in the reading of the artwork, but maybe so do John Hughes movie soundtracks . . . Which basically a Hughes movie is an MTV movie . . . In that vein, I made a playlist for the MCS, choosing songs for each piece in the exhibition, that in some sense, reflect the artwork. MTV Altarpiece’s song is “Pour Some Sugar on Me” the Def Leppard ballad that aired based on paid, call in, phone requests every day for a record run in the ’80s—all before Carson Daly’s Total Request Live . . . You access the MCS songs with your iPhone . . . It’s free.

I am curious about the aesthetic of MTV Altarpiece. To me, compared your other work, it looks really “trashy” and punk and incorporates a lot of the cultural tokens over which the American Culture landscape is still fighting. In particular when it comes to question of the incorporation of signifiers that some so-called minority immigrant communities want to claim solely for themselves?

MTV Altarpiece is not very well put together . . . At the time there was no conservation term for it, like “inherent vice,” in which the material something is made of, by its own materiality breaks down the whole conservation process and the piece itself . . . Like Lizzi Bougatsos’s ice sculpture (Self Portrait, 2012, The Dikeou Collection) . . . MTV is thrown together, but it is also reflective of the punk, trashy way graphics, videos, art, music were visually implemented in the ’80s, using color xeroxes, quick cuts, colors from spray cans . . . Packing materials . . . So yes, it’s look must seem more trashy, punk . . . I am not interested by a white cube aesthetic and throughout all spaces I exhibit, I try to challenge that aesthetic. In the California St space (MCS) all the holes in the walls of the Dikeou Collection remain, as ghosts of what’s been before, as do certain Collection pieces. In the Pop-up—that it is a record store reflects very much the place and atmosphere of MTV. At Foyer-LA, that it is an artist run space and grew out of an artist’s studio, and is a resting place to exhibit art in proximity to the studio reflects this idea, of the breakdown of the white cube, and makes and shakes ideas of what and where a gallery is and can be . . . It makes sense that this breakdown happens outside of New York, as historically this breakdown happens outside the epicenter and that it reaches more than just the art community . . . I think more along ideas of flatness, than in terms of tribe . . . How that translates among diverse communities and markets becomes more about fighting and/or absorbing the natural market mechanisms. The minute something is free, the market finds new ways to commodify it . . . Napster and Video Art in their initial stages, and more contemporaneously streaming and NFTs . . . Initially streaming was free TV and digital art, free art . . . Now there are streaming subscriptions for CNN and Discovery . . . So you pay for and get more specific and curated streamed content, or you pay for a specific moment, a zeitgeist moment, in an explosively priced NFT . . . Come to think of it CNN and MTV originally began as subscriptions in the ’80s . . . Buyers and subscribers beware.

I am an artist who does so so many things, I have invested nearly all my life in questions of class and race and politics and I still wonder who should say what to whom and under what conditions . . . And with a body of work to reflect that as varied as performance, videos, paintings, drawings, fashion lines, ceramics, multiple web sites, I needless to say, have very little means to even store a piece like this over such a lengthy period of time. Could you tell me how you did it ? Did you simply remake it, redo it from scratch or could you just pull it out of storage?

There’s a great documentary called “Scratch”, by Doug Pray. It’s about the history of DJs . . . ’70s to 2000s. And what is a DJ . . . They take a given and make something out of it . . . They spin . . . So yes, it’s made from scratch . . .

Awe/ful, 2018, wool, acrylic, cotton, metallic fibers, 45 x 64 inches

Terri Friedman’s “Rewire” at Cue Foundation (September 2–29, 2020) directly engages with the psychic reality of our strife-filled current times—but rather than critiquing the subjects at hand, her work delves into the tender drama at play within individual brains and bodies worldwide. Friedman’s woven paintings are abstract, colorful, and multi-textured cross-sections of brains under the spectrum of emotion, with a gentle suggestion to consciously alter the patterns and pathways away from a default of negativity, as she states: “cultivating elevated states and happy hormones is a political and personal weapon against indulging in despair.”

Interview by Brandon Johnson

This body of work is both a sign of the times, and a suggested antidote—to “re-wire” the brain from the current default of angst and worry. Was there any specific event or spark that initiated this series, and over what period of time were the works made?

This series is part of a larger body of work that I have been working on since the last election. I think the national unrest and political volatility sparked my own personal anxiety. My work journals the world around me and my own inner world. I’m wired for worry, but between Climate Change, the national and global uncertainty, racial inequity, the fake news, our President . . . I could go on, I just started feeling despair. My weaving became my medicine. An antidote to all the heartbreak and grief. What if I made protest posters like Sister Corita Kent with words, color, and abstraction. Tapestries that were healing, life affirming, but also agitated yet affirmative screams. Brain and cognitive science has found that the brain, which we assumed was not plastic after childhood is actually able to be rewired. This is neuroplasticity. So rewiring which is actionable is about repair. It’s optimistic.

The suggested connection between neural networks and weaving is made visceral through the variation of textures, sizes, and methods by which the materials are adhered—the end result being an expressive diagram seemingly composed of tissue, vessels, and other bodily matter. For this reason, did your process of weaving feeling extra charged either psychically or physically? How was it to make this works?

That’s such a great question. No one ever asks how it was for me physically or psychically to make this work. It’s actually a very important question. I am so interested in the somatic and psychological experiences of artists. Weaving can be back breaking. Such physical work. But, also immersive and meditative. Sometimes I just lose track of time. The repetition kind of puts me in a trance state. Psychically it was exhilarating. I just love working with so many textures, fiber, and colors. It is like a fiber orgy. I have accumulated so many clear tupperware boxes filled of colored fibers the past years. All kinds from naturally dyed wool to cotton piping which I paint with acrylic paint to metallic to acrylic to hemp and more. I draw out the piece ahead of time with diagrams of textures/fibers/colors/warp design and graph it out. Then I select all my fibers and begin. The pre-weaving process is lengthy.

You mentioned Sister Corita Kent as an influence in terms of subject, spirit, and presentation. Are there any specific artists or weaving traditions that have informed your work on a more material level?

I came to textiles late in my career, 2014. I painted and made kinetic sculptures before that. Though the connective thread though all my work has been color, body, breath, and brain. I am most informed by painters/artists (mostly women) who indulge in color and odd materials like Joanne Greenbaum, Sarah Cain, Shara Hughes, Judith Lynhares, Kathy Butterly, Rachel Harrison, Katharina Grosse, Katherine Bradford, Nick Cave, Polly Apfelbaum, Jeff Gibson, Franz West, and more. Textile artists that I look at are Sheila Hicks, Hannah Ryggen, Josep Grau-Garriga, Anni Albers, Magdalena Abakanwicz, and numerous younger living artists. On a material level, so many artists who stretch materials are interesting to me. I define craft as attention to detail. So, it’s a broad interpretation.

Enough, 2018, wool, cotton, hemp, acrylic, metallic fibers, 77 x 50 inches

Text also appears in these works in the form of single words or short phrases—often slanted toward the negative, such as AWE/FUL, E/NO/UGH, IF ONLY. Did these words arise in your mind organically (almost mirroring their presence in the artworks) or was there a process from which you arrived at them?

The words are more disbelief or antidotes to anxiety: like Pause, Awake, In/hale/ex, and more. they can be either positive or negative. They are ambiguous. AWE-inspiring + awFUL (thus AWE/FUL). ENOUGH connotes ‘stop! enough!’ OR I am ‘good enough’ as I am. IF ONLY is regret, but also kind of romantic, living in the past, kind of naive because it’s done. What good is regret? Just move on and take action now, in the present moment. Awake is a reminder to wake up to the volatility and it’s a call to action. I like small benign or ambiguous words. Words that are spacious and give the viewer a roll in completing. I don’t want to lecture, they are more of a suggestion or direction. They blend in and are almost camouflaged. The words arise at the same time as the drawing. They are like another color or shape. I don’t illustrate the words, but I do try and have the piece emote with color and form what I am feeling. Like the burning pink, so hot and inflamed with ‘Awake’. OR the eye chart and busy anxiety of E/NO/UGH. I like abstraction and words because they feel generous and not didactic. Immersive.

Oxytocin, 2019, wool, acrylic, cotton, hemp, chenile, metallic fibers, 77 x 70 inches

One of my favorites is “Oxytocin” which is composed mainly of shades of gray, with a half-smile of rainbow drooping off the side in a way that is bleakly humorous. There is a certain messiness to these works that communicate a degree of confusion and stress, but the bright colors and titles such as “Looking for what is not wrong” indicate an underlying search for the bright side. Is perseverance part of the thesis of this exhibition?

Oxytocin is a happy hormone like serotonin and dopamine. My titles and palettes do reflect perseverance. Rewiring takes effort but is a positive action. In some ways, this work and the titles are my attempt to rewire my brain for positivity given how dark and bleak the world feels right now. And, they are remedies for the personal and national anxiety and grief. So much loss with COVID, the criminality of our government and more. Humor or delight are very important to me. I had an art history professor in college use the term ‘sickly sweet’ to talk about Chagall’s work. He did not like the work and was disparaging. And, all I could think was ‘I love sickly sweet’.

Devon Dikeou, Do I Know You?, 1991 ongoing

Devon Dikeou’s retrospective “Mid-Career Smear” opened at the Dikeou Collection, Denver, in February 2020. Soon after the COVID-19 pandemic forced art venues around the world to close their doors and postpone their programs. With the exhibition on pause, we reflect on the background and ongoing context of the show and work included.

Interview by Brandon Johnson

What does the “Mid-Career Smear,” a retrospective, mean to you as an artist at this point in your career?

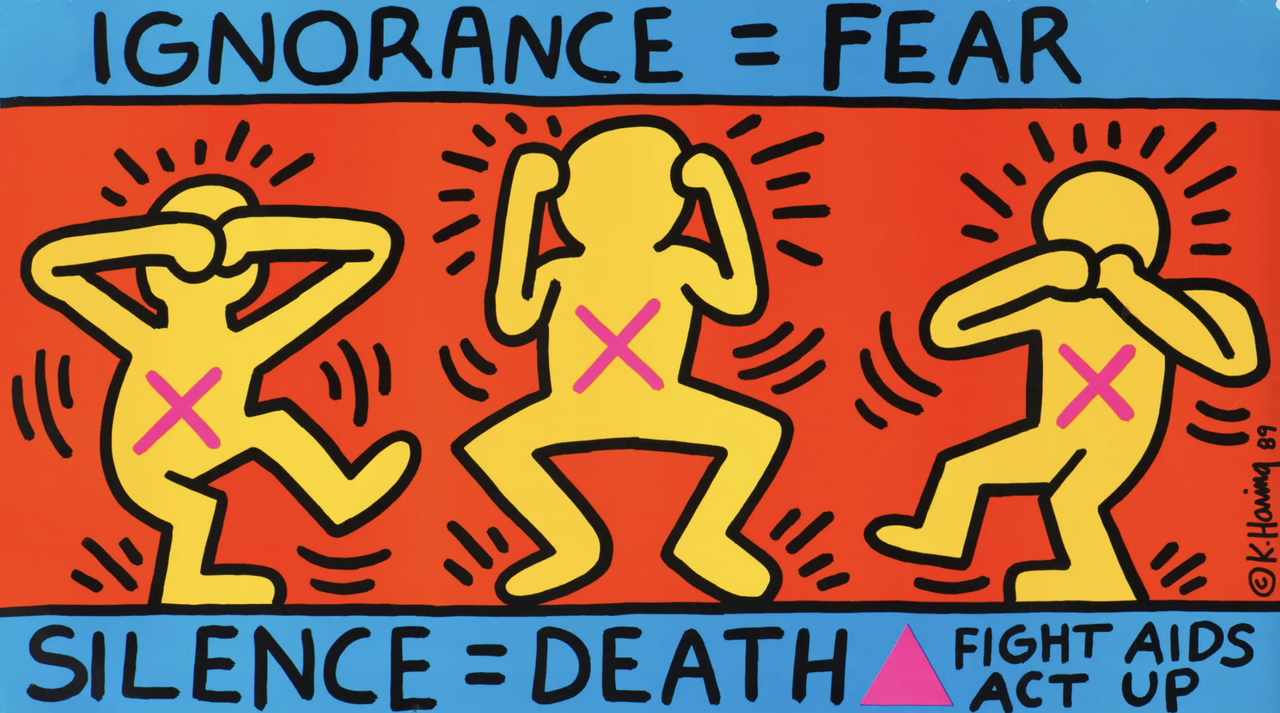

Hmmmmmm well given the circumstances it’s hard to speak on MCS. My hope is sometime in the future we can all get out to see all the art that is out there on view (but closed at this time) and then enjoy, wonder, be inspired, because at this time it’s needed more than ever. We are living in our version of the bubonic plague . . . let’s try to think of how art influences us even if from centuries, generations before, or more currently . . . there’s Bruegel’s “The Triumph of Death”. . . which fills the well of what life might have been like. . . even as it was painted later than the actual pandemic. Other artworks in the 20th century offer a different take. Rothko’s chapel in De Menil Museum campus . . . Rothko’s architecture and paintings in the chapel reflect that along with the monumental Barnett Newman sculpture, “Broken Obelisk,” that flanks the chapel structure—all non-denominational places of solace, worship, meditation. And then there are Norman Rockwell’s Saturday Evening Post magazine covers during the Great Depression and WWII, a great example, “The Four Freedoms.” Another seminal piece is Robert Indiana’s “LOVE” made in 1967 during the Vietnam War. . . Much less Keith Haring’s AIDS awareness posters and paintings, during the AIDS epidemic: “IGNORANCE=FEAR.” Art fills a special place. A comfort, a critique, an illustration, a reflection of life’s strife, as well as moments of jubilation. My work of 30 years gets nowhere near all those aspirations but tries very hard to touch them.

Pieter Bruegel the Elder, The Triumph of Death, c. 1562

Keith Haring, Ignorance = Fear, 1989

While you were born and raised in Colorado, most of your development and exhibiting as a visual artist has occurred elsewhere, with perhaps your most formative period being in New York City during the 1980s and 1990s. Can you speak about this and what it means to show a deep survey of your work in Denver to a mostly Coloradan audience?

Well Colorado and Denver, these places, were my first tutorial. Really the Denver Art Museum and Denver Public Library were the retreats I ran too, á la Claudia in the Mixed Up Files of Mrs Basil E Frankweiler. The library is where I read that book, DAM is where I saw all the art I could—from Armand Hammer’s exquisite soup tureen collection to pop paintings in the DAM Bonfils Gallery including a mesmerizing drugstore window by Richard Estes. One show is about objects, soup tureens, which are magical in a Maurice Merleau-Ponty way, even if you don’t know phenomenology. The other drew me into a window, which paintings are, a painterly window, and as realistic as can be imagined in content. What are windows, of course they are also mirrors. Manet teaches us with that in “The Bar at the Folies Bergere” and the Velvet Underground with their song “I’ll Be Your Mirror,” inspired by Warhol, then appropriated by Nan Goldin’s ‘90s slide installation of the same title. These windows, mirrors, and objects: they are “The Lion, The Witch, and the Wardrobe” given and exposed to just one among many youngsters in Denver in the only Gio Ponti building in America and in my case the Eugene Field Library. The Ponti BTW is where I first applied for a group show with “old school” slides. The curators were Deborah Butterfield, Peter Plagens, and Marcia Tucker. My piece “Security Secure” was selected for the show “Colorado 1990.” Weirdly, the best thing happened . . . during the opening the lighting staff left the cherry picker in front of my installation of gates and glass, not realizing my installation was a part of the exhibition. Inbetween that gate and glass installation . . . I also ended up with a few Encyclopedia Brown books . . . all overdue. Another inbetween.

Devon Dikeou, Security/Secure, 1989 ongoing

As a collector I know you value an individual’s ability to view an artwork over a period of time and see how their relationship to the work changes—an essential notion to the Dikeou Collection. As an artist revisiting your own earlier artworks, did you find that you relate to them differently now? Any specific examples you can offer?

For sure. But also not simply because of MCS. As a publisher/editor of zingmagazine and by extension a collector with the Dikeou Collection, both kinda took over. My art practice lost its ummmph, just rested. I saw to those other two uses of my energy as part of my practice more thoroughly. And they were well-tended. So there were many zing projects that opened the way to viewing so many artists and other creatives. And the Dikeou Collection like zing was a platform to share and I hope we have . . . From time to time during this less productive period of my art practice, cause I’m such a weird archiver I’d look at some of my work from years past in the binders above the computer. Looking at images of work reminded me of my sometimes prescient ideas as a practicing artist then, all in hibernation. In those moments I was reacquainted with old friends and that re-immersed me in their boldness, i.e. the “Here Is New York” security gate series, most recently shown at James Fuentes, as well as many little bits that at the time I thought were supremely unmonumental . . . Surprisingly, little turns out to be big, just like in Alice in Wonderland. The Rolodexes are a crowd favorite . . . they almost were not included.

Do you identify primarily as an artist? If so, how do you believe this has affected your approach as a publisher and a collector?

Yes and no. It’s a trifecta, I think. As an artist in the mid-late ‘80s and early ‘90s I’d visit and do the gallery tour. Sometimes alone sometimes with others. Then you’d gobble up the Friday NYT and the Wednesday Village Voice. I remember a quote from VV somewhere along there, that went like this . . . “The Cindy Sherman show at Metro Pictures is like shopping at Bergdorf’s at Christmas. At Paula Cooper, the Jennifer Bartlet show which has orange painted chairs and other objects in front of the paintings, a collector was heard saying as the dealer left the room, ‘If we buy it, can we put the chair in the closet’”. It’s funny as an artist to hear or read those words. And then as always my thoughts kinda come from words, and my work didn’t really get much written attention so I started writing my own. You’d see all this amazing work of your contemporaries and why their work wasn’t being shown or collected, much less published. And that’s the genesis of both my publishing and collecting instincts. Hence both zingmagazine and the Dikeou Collection, which by the way, along with just being artist, editing is perhaps the most powerful tool one can possess in all three practices.

Devon Dikeou, Between the Acts, 2014 ongoing

Who/what have been your greatest influences over the course of your career? And how have they, if at all, influenced “Mid-Career Smear”?

I have a daily diet of 24-hour TV, but really it’s the same as everyone else. Learning, looking, curiosity, inspiration. No matter where these impulses come from . . . but most likely they come from close to home. For me that would be from my mother LSD and her friend Frank for decor and fashion, both of which are a huge part of my practice. Don’t think of decor and fashion as the frill but the set. It sets you inbetween you and the people you meet and see. My father—space and the relation to it, what a space like a parking lot could mean, and understanding what that represents . . . something inbetween big and small, commercial and other. Brother, it’s belonging and knowing you always will, cause often there are cracks. My fellow, who helps me execute, is out front when I hold back. There are many more: the homeless that pick you up off the street after tripping, other artists that feed you ideas and suggestions, edits you may not have considered. There are the teachers, Wendy Edwards, at Brown University, Ursula Von Rydingsvard at The School of Visual Arts, Mrs Emery’s after-school art at Graland, Mr Burrows at KDCD, all segues and that’s not all. . . There’s the professional curator who directs and guides and intuits your vision to fruition . . . not an easy task, and one that has taken over seven years and lots of different considerations, by Cortney Lane Stell, and she was the inbetween, behind the curtain . . . However, it’s always, always a new thing, an old thing each day . . . sometimes it’s just sleep. And sleep is something to try to look forward to . . . another inbetween space . . . be brightened because you’ve found it and surrendered if even in a small repetitive way, which is the inbetween of everyday . . . sleeping and waking.

Known for his signature expressionist paintings and drawings featuring cartoon-like imagery, Christian Schumann blends landscapes, still-lives, and figures in his artwork. Born in Rhode Island and raised in Texas, Schumann graduated with a BFA from the San Francisco Art Institute in 1992. With influences ranging from the underground art scene to the animation and video art realms, Schumann creates works that are at once imaginative, subversive and pop-culture infused. Schumann often combines text, abstraction, and figuration to create work that evokes a sense of imagination, and drips with an underlying political and social commentary.

Interview by Mauricio Rocha

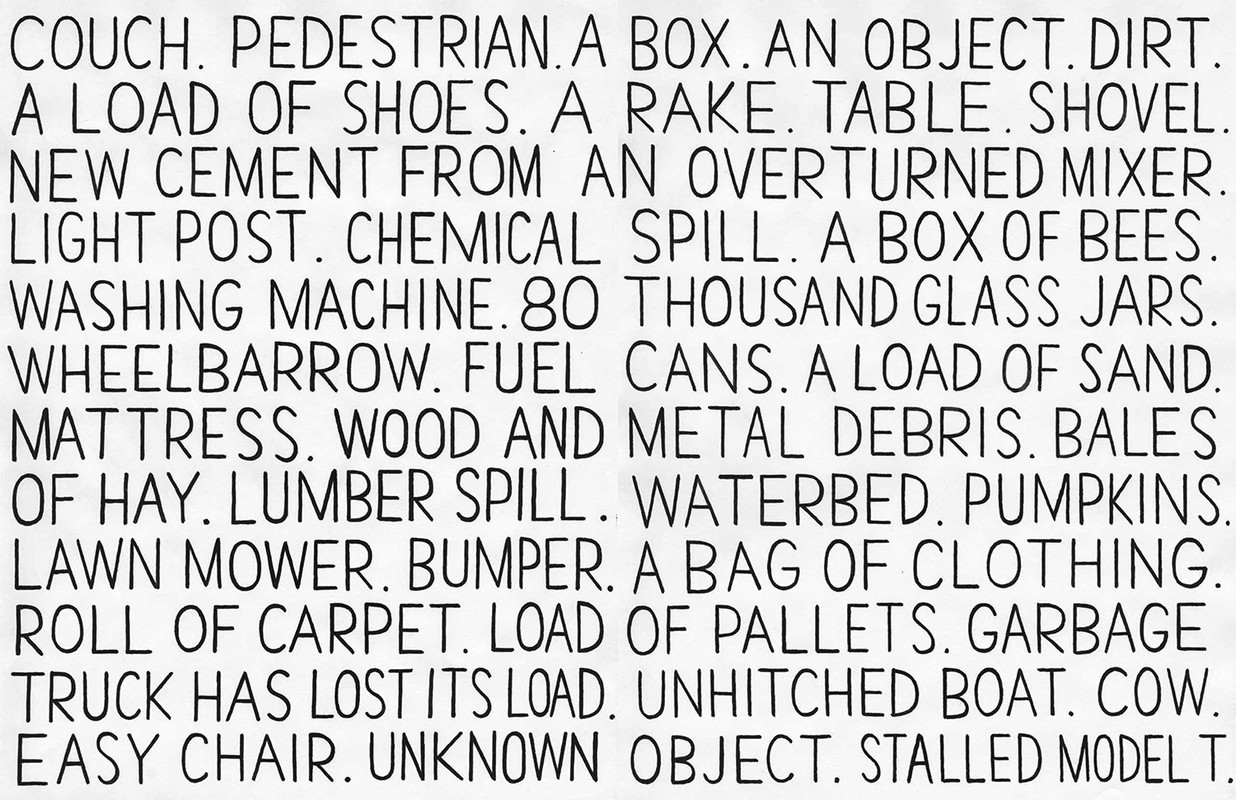

What inspired you to transcribe traffic reports, as in your work “Obstacles” featured in zing #25?

I happened upon radio traffic reports on Los Angeles radio stations incidentally as I went about scanning the radio looking for anything interesting to listen to. While most stations were fairly unlistenable, the one thing that universally stood out was the distinctive obsession and personality of the Los Angeles driving experience that stood out in the traffic reports. There was an excited joy in reporting every turned-over trailer full of mangos or stray dog running along a highway. The incidents stood out so much I decided to record them as a list as I heard them.

Do you view obstacles as a negative or positive experience?

Too many obstacles can be draining and I admit I find them to be a negative, although ideally one could take a Zen Panda approach to them, waiting to see if what at first seems to be a negative ends up having a positive effect somehow. The paths of our lives are directed by obstacles to varying degrees, depending upon one’s luck and tenacity.

Why did you want to focus on the text and language of the reports, with no visual representation?

I think reading text describes an image perfectly well in one’s mind. I thought of writing the text as a form of poetry, not exactly concrete poetry but something akin to that. I never considered using visuals and thought of the lines and pages of text as a visual in itself.

I view this project as a form of poetry as well, and sort of an endless one at that. The obstacles in the traffic reveal something about the people of LA in the sense that what they carry with them, matters most to them. Do you think these “obstacles” reveal LA’s personality?

Yes, as you suggest, what physically matters most to people is what they choose to carry with them from place to place as they move. Casualties of these moves constantly end up shattered along the pavement: family photos, clothes, and mementos scattered to the wind and possibly causing terrible accidents along the way and influencing the lives of others.

In Hollywood fashion, I think there is an element of entertainment to the reports. In a city that revels in police chases that are televised as a sort of sporting event, any unusual activity that takes place on the highways constitutes a major element of everyone’s daily lives is noticed and transformed into spectacle. With a general lack of weather to report on perhaps these unusual obstacles fill in as a replacement for “dangerous” weather systems that would ordinarily maintain the interest of listeners.

I noticed many repeat obstacles in your work: varying types of debris (metal, plastic, wooden, glass), animals (dogs, a horse bench, a goose, a box of bees), unknown objects, furniture, and food (avocados, chocolate, carrots, grapes, red peppers, lemons). Do you think these objects are an accurate representation of Los Angeles?

In a utilitarian sense, yes, the city is revealed by its highway detritus. It almost feels like an engineering problem, a side effect of daily use which must be constantly dealt with. Los Angeles is an overburdened hub of transit for international shipping and food transport which results in the occasionally overturned vegetable trailers. Additionally, I omitted many entries in order to avoid too much repetition of the most popular items: gardening equipment, ladders, mattresses and furniture. Lawn care workers are pretty ubiquitous and there is generally a lot of mobility in people’s lives so a combination of flux and upkeep pervades the transit routes. Patterns, habit, entropy at the edges.

Do you have a personal connection to Los Angeles?

I lived there for six years or so with my family and our daughter was born there. I don’t currently have a great personal bond with LA apart from friends that live there.

Do you think the early 2000s were a different time than now?

Not really. I think all the elements that comprise our current state of affairs were in play in the early 2000s as well. If anything I am disappointed in the lack of long term change in our global societies over the past 50 years, let alone the past decade. The patterns of our world are older than we think, its obstacles presented as a spectacle of repetition and entertainment while simultaneously hindering our progress.

That is interesting you find the repetition of society as hindering our progress. That is true because if we keep doing the same things, how will we ever evolve into something different, or better? Do you think that our US society is too comfortable with the familiar and afraid of change?

The structures built by previous generations to inhabit provide for maximum convenience and minimum effort (providing one has funds to support it). Stepping out of these pre-existing paths requires effort, learning and a willingness to discard old things. Those are all very challenging barriers to breaking the system of patterns we all function in. It’s as though a collective neurosis is directing the continuation of increasingly pyrrhic habits of our societies in order to hide us from the reality of what lies ahead.

Take the most common element of highway debris for example: lawn care equipment. These devices are used expressly for the relentless maintenance of a centuries-old European tradition meant to imitate bourgeoise status which exploded across 20th Century American real estate development. Here we are now in the 21st Century maintaining an outmoded status ideal, which apart from being completely detached from necessary to a home environment, also creates a huge economic and environmental burden. Fertilization chemical run off, the burning of fossil fuels to power lawn mowers and their transport, the slow-moving lawn care vehicles also clogging freeways with debris. I believe that the removal of the traditional grass front lawn would have positive repercussions. The benefits would be limited but we are faced with the fact that most aspects of our lives are similarly outdated and the structures built to maintain this toxic civilization are at a breaking point. Human civilization is trapped on the global 405 of its own making.

What sort of obstacles do you see in society’s way in 2020?

We are our own worst obstacle.

After growing up between Denver, Colorado and the Smoky Mountains of Tennessee, Rachel Dalamangas earned her MFA in Literary Arts from Brown University in 2011. She is an author who specializes in creating short works of fiction, non-fiction, and poetry and is currently based out of New York City. Her work has been featured in BOMB Magazine, Bookslut, and zingmagazine, among others, and explores humans’ different states of consciousness. We spoke with her to discover more about her writing process, inspirations, and the future.

Interview by Mauricio Rocha

Your short story in zingmagazine #25, “The Leftovers,” is centered on two elderly couples coming to accept and comprehend the final phase in their life cycle. What do you think the afterlife holds for your characters?

I was writing this story around the time my father was succumbing to terminal cancer. He and I used to go hiking all over Colorado when I was a kid and we would have lengthy, winding, abstract, unlikely conversations about the nature of existence. So I was thinking a lot about what consciousness is and what happens after we die. I think the way the four characters examine the possibilities of the great unknown reflects my agnostic worldview. I’ve always been fixated on death and dying and states of consciousness.

That said, I think reincarnation is my favorite answer. I can imagine Rose becoming an asocial small mammal, perhaps a hedgehog or a mole. Maybe Debbie is freed from the cycle of life and death and transcends into a state of being some sort of otherworldly figure. The Roberts are clearly soul mates, so I think they will have a great love affair in the next life.

I enjoy the philosophical aspect to the story, it has a very stream of conscious feel to it, the way the characters converse with each other and contemplate the end of the world by way of robots, UFOs, global warming or an “orange blast.” It is scary stuff but told in a light-hearted way. Do you like to play with tone and voice in your work, or is something that happens organically?

It happens organically and then I notice myself doing it so I start to do it even more.

Your story takes place near a dog-food factory. Being from Denver, I know that neighborhood as Swansea. Was this one of your inspirations for the setting?

It pleases me so much that you saw the Swansea neighborhood of Denver in the landscape of the story. I was imagining a nameless, nowhere-in-particular place that was an amalgamation of “left behind” places in America I’ve passed through, many of them in Colorado.

I noticed many uses of the color green throughout the story: turtles, a frog, a stegosaurus, teal eyes, turquoise, and even aliens. What does the color green represent for you?

Are all those things actually green? I think aliens are gray, right? Aren’t turtles really more like a bunch of different earthy brown tones? I don’t think green is symbolic of anything for me, at least not consciously. I think all that color is just what my mind’s eye conjures when I think of Colorado.

Photo: Levi Mandel

Time seems to be a prominent theme in the story, the passage of it on Earth and the generational gap between the young and old. Do you think time is something to fear or embrace?

Both. Personally, my life always feels like it’s going so slowly, but for some reason it still seems like I’m getting old incredibly fast. But there’s no choice other than to fear and embrace the passing of time. While I don’t look forward to getting older per se, I’m excited about (hopefully) being really old someday because I think I will be great at being a weird old lady. When I’m walking to work on the Upper East Side, I pass these little old ladies in their leopard print berets and big sunglasses and fuchsia lipstick and am taking notes because I’m secretly planning a fabulous wardrobe for when I’m old.

I love that you are already planning your future wardrobe. I look forward to being (hopefully) wiser, and more refined. Is that something you are looking forward to as well? Or do you think that’s something we can start doing today, in our younger years?

I think what’s important specifically in terms of aging well is to drink more water and don’t forget to put lotion on your neck.

The squirrel in the story is funny and it pivots some of the characters against nature. How do you feel about animals and nature?

That’s an excellent question and now that you mention it, I think the squirrel is actually the personification of my own pathetic, toothless misanthropy. When I was writing this story, I was going through a phase where I was trying out nihilism a little bit because cancer is a relevant occasion for nihilism. You can’t stop cancer. You can’t control it. It’s this slow-moving, unstoppable, gruesome, unfair, profane, meaningless disaster that happens. There’s no point and no good reason and no silver lining.

But, there’s also the realization that no matter how big or dramatic your problems feel to you personally, they are of equal relevance to a squirrel’s in the greater order of the cosmos. That sounds so negative, but it’s actually humbling and awe-inspiring to remember how small your existence really is. So for me, it’s important to be emotionally honest about difficult circumstances because sometimes life is just shit and the only way through it is feeling however you feel.

Your story contains moments of magical realism, where dreams and visions blur into real life. Moments like when Rob sees his brother hatch from an egg with egg beater hands, or the light Bert sees at the end of the tunnel. Do you view everyday life as magical, or extraordinary?

I think I’m interested in how the surface texture of reality has changed rapidly as a result of technology. I’m interested in how literary realism attempts to respond to an accelerated, interconnected, image-driven world. I’m also interested in how consciousness works and how the human mind constructs reality especially as technology improves at replicating the human mind and the human mind changes in response to technology.

So I like to explore states of consciousness, and I like to write narrative circumstances where alternate interpretations of what is happening are all equally possibly true and where there isn’t necessarily any need to resolve the truth.

How has the novel, The End of Vandalism by Thomas Drury, influenced your writing?

Well, it’s an extraordinary work of literary realism because of how Drury cannily toys with style. The End of Vandalism isn’t a book I’m sure how to approach critically. It’s a book I keep near my desk and read a little of at random to get the prose in my ear before I start writing. There’s something very lively in the beats of wry, easy humor. It’s the kind of book that wakes me up and reminds me of how much is possible in fiction. Also, it’s one of the most hilarious books I’ve ever read.

Are there any upcoming projects you are working on that our audience can look forward to?

I’ve been working on a short story all year long and it’s still not done. I am probably the slowest writer in the world.