Devon Dikeou, “WHAT’S LOVE GOT TO DO WITH IT?”: Unsafe At Any Speed, 1991 Ongoing, 18 x 24 inches

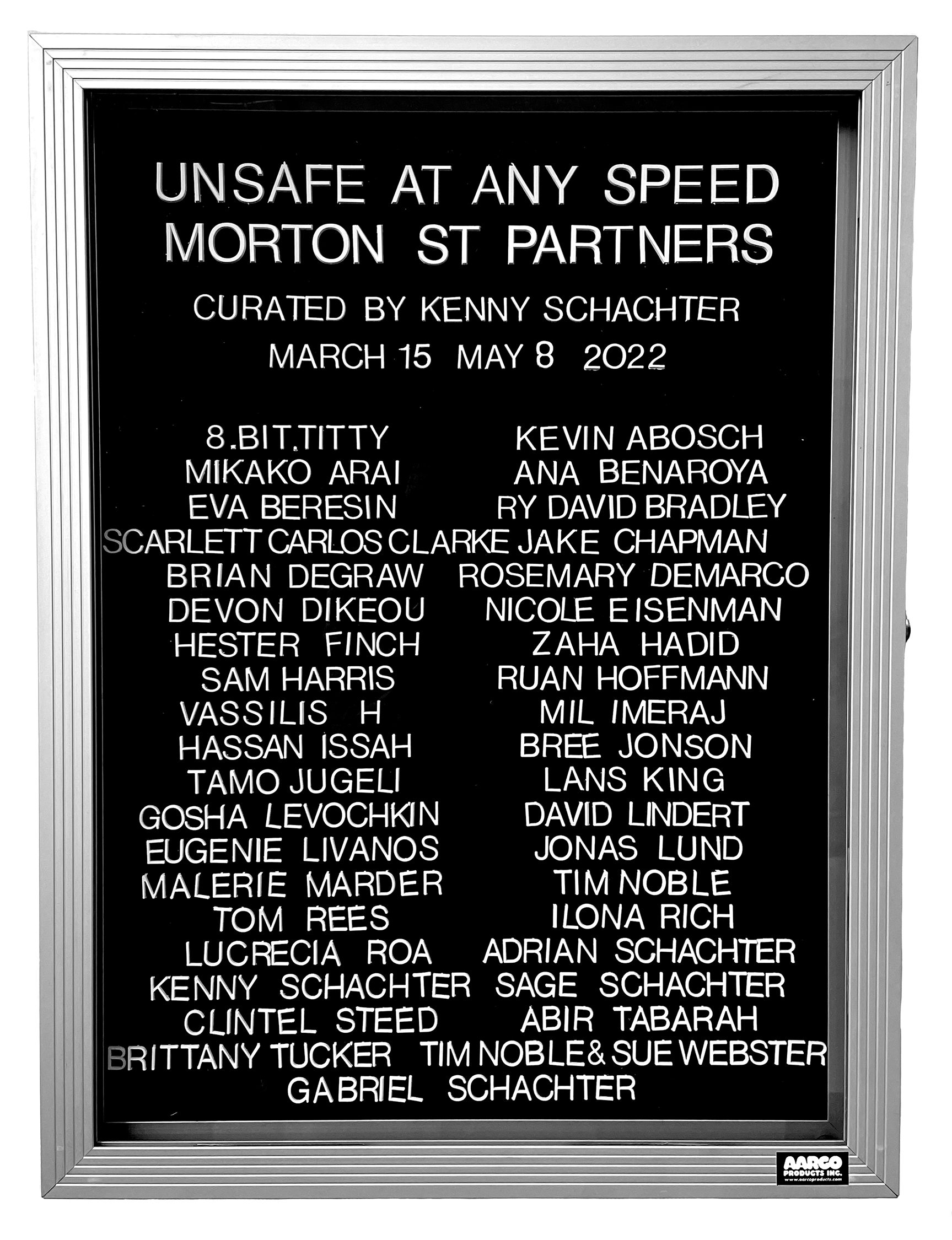

Recently opened exhibition “Unsafe At Any Speed,” curated by omnipresent artist, writer, curator, and dealer, Kenny Schachter, is a return not only to his curatorial New York City group show roots, but also something beyond this. Schachter widens the scope even further to incorporate his post-1990s activities by including his own work, the work of his family members, and last but certainly not least, collectible cars—reflecting his own collecting interests, past creative partnership with architect Zaha Hadid, and his current collaboration with Morton St. Partners, who play host to the exhibition. Founded by Jake Auerbach, Tom Hale, and Ben Tarlow, Morton St. Partners is a curatorial project merging the worlds of contemporary art and collectible cars. Located between a “small-batch” donut shop and CC Rentals (a New Yorker’s insider alternative to U-Haul), the space at 16 Morton St is conveniently equipped with a garage door opening out to a quaint West Village street adjacent to Seventh Avenue. Inside you’ll find “Unsafe At Any Speed,” the partners’ inaugural show, a sprawling exhibition featuring a global representation of contemporary artists, with names both familiar and not so familiar. From paintings to sculptures to NFTs, the show seamlessly includes three cars—a 1970 Lancia Fulvia Rallye, clear-sided 1969 Citroen Mehari, and the Zaha Hadid concept Z Car. With collectible cars setting records at auctions and becoming the focus of institutional exhibitions at venues such as MoMA, the show and space represents a new curatorial front on the border of art and design. “Unsafe At Any Speed” is on view by appointment at Morton Street Partners through May 8, 2022.

Interview by Brandon Johnson

Many in the art world first came to know you through your 1990s pop-up group shows in New York City. Does this New York City group show feel like you’re coming back full circle in a way?

Kenny Schachter: 100% feel the same as my early initiatives—large group shows, all over the place and wildly inconsistent levels of quality! Ha. But ultimately, tighter, and more ambitious. With 30+ years of experience under my belt.

The artists in “Unsafe At Any Speed” are a diverse group, hailing from countries around the world. How did you discover their work and what does it mean for you to bring them all together?

KS: There are 38 artists from 15 countries the widest breadth geographically of any show I’ve done in my career. The advent of social media, which blurred the physical boundaries and shrunk distances between people played a large role in the discovery and organizational process. It means a lot of work is what it means! Also, it’s very satisfying to reach beyond my immediate circle and work with such a broad, culturally diverse community of artists.

Installation view; foreground: Citroen Mehari; background: Zaha Hadid, Z Car; photo: Phoebe d’Heurle

The show also features work by members of your family. Back in 2015 zingmagazine published a book of your family’s art titled Family Affair. What’s it like having a family full of artists?

KS: Art is one of the central threads that binds my family, it’s the most satisfying experience I have ever had in my life, combining the two things I love the most—art and my family. In fact, the only things in life I truly care about as much as I do.

Installation view; left: Lancia Fulvia Rallye; photo: Phoebe d’Heurle

On that note, you are an artist yourself and multiple works of yours are in the show including an NFT, a chair, and an oil painting. When did you begin making work yourself, and what inspired you to be an artist?

KS: I have made works since I was a kid (in one form or another—largely collage from magazines applied directly to my walls in Long Island). I had a miserable childhood and living internally through rejigging existing imagery was a way to assuage my feelings and express myself. Not much has changed in 50 years, except now I get the beautiful experience of getting to share my efforts with others whereas as an isolated child it was a very solitary pursuit.

Your collaboration with Morton St Partners is serendipitous given your shared interest and investment in collectible cars. How did you cross paths and decide to embark on this exhibition together?

KS: Every year I sell a portion of my shit—make that bits of the collection I have painstakingly put together over the course of my entire art-life—to contribute to making a living; this annual event is a single-owner online sale at Sotheby’s called the Hoarder and there’s been 3 to date. I met Tom Hale, a partner at MSP and art collector, two Hoarders ago.

Installation view; photo: Phoebe d’Heurle

How did Morton St Partners originate? And what relationship do you all see between collectible cars and contemporary art?

Morton Street Partners: Despite working with different companies/niches in the classic car industry, the three of us bonded over our relative outsider status as younger members of this generally older segment. Here in NYC there is a particularly closely-knit small group of collector car experts under 40, and each of us was actively engaged with this group, even attending a quarterly “industry dinner.” As the pandemic hit, we were all simultaneously looking for a new challenge and direction, hence the launch of Morton St. Partners. That automobiles should be regarded separately from any other design movement of the 20th century seem to evolve from both the private nature of the world that already collects them, and the idea that their utility prevents a serious aesthetic discussion. We see no reason to disregard the artistry of an automobile simply because it is self propelled. It’s our experience that the conversation around automobiles engages all the same language of scarcity, materials, cultural relevance, provenance, and epoch already familiar to established collecting spheres. As for Kenny, Tom Hale was previously acquainted with him and had frequented his “hoarder” sales at Sothebys, so once we secured our new premises we could think of no one better to curate the first show.

KS: I have a democratic, non-hierarchical approach to art (and life). I don’t differentiate between a poster, a chair or a painting—or cars—when created with love and passion. Industrial design, namely 1970s sports cars, were my gateway drug leading to my art obsession.

Photo: archive National Gallery in Prague

Romana Drdova is a Czech artist whose works borders on the lines of fine art, fashion, and design as it engages with themes of perception and human interaction in a time of “data smog.” Graduating from the Academy of Fine Arts in Prague in 2017, she’s gone on to solo exhibitions at Czech institutions MeetFactory and Karlin Studios, along with international presence in Vienna, Berlin, and Liege, Belgium. Her project “Mapo Tofu Masks: An Asian Love Story” was published in issue #25 of zingmagazine. Most recently, Drdova’s work is being exhibited at the National Gallery in Prague, curated by Adéla Janíčková as part of The Empathy Award, on view through February 2, 2022.

Interview by Lenka Bakes

In your first interview for zingmagazine (2019) you spoke about drawing inspiration from Korean culture, the bond you’ve made to China as well as the impressions you picked up during your time in New York. It’s obvious you keep a close eye on various cultural practices and they inspire you in your work, which you’ve described as a “spiritual translator”. This practice led you to create your first series facemasks, which zingmagazine published in New York at the beginning of 2018.

I’d like to ask what has changed in your professional life? Where have you drawn your inspiration from and what has interested you during these past two pandemic years? Have you created another collection of masks? What was the impulse behind facemasks back then? Did the masks resonate with people and in public space, which was affected by the pandemic for much longer than we expected?

Much has changed since society has changed and is still changing as a result of the pandemic. My main shift has been in realizing the quality of time I want to devote to self-realization. I’ve discovered that this is the only way I can work in society and do something for it, it’s also the only case in which I’m at peace with myself.

My work with facemasks, which I started creating in 2017 and was published by zingmagazine, had the character of an unusual fashion accessory. Today, face masks have become an essential part of everyday life. For the new collections, I used themes dealing with the segregation that the pandemic has brought on a large scale.

During the past two years the boundary between one’s inner and outer world and the individual and their surroundings has deepened. You often articulate relationships in your work or visualize their absence. This makes me feel that you may be interested in this boundary. Have you experienced something like this personally?

The gap between what we feel internally and how we act or look in society is alarming. The pressure that brings the suppression of achievement is a disease of society. I’ve always been interested in the surrounding world and its method of communication. In several exhibitions my work was concerned with how visuality or barriers form our bodies and mind. For example, at the Futura Center of Contemporary Arts I created a city light billboard where sexual and romantic motifs were featured along with seductive images. My intention here was to create a scan of my own thoughts, what I’m really thinking about when I’m waiting at a tram or bus stop.

Photo: archive National Gallery in Prague

If we zoom in on interpersonal relationships, we can return to the work you first presented last autumn at the group show The Unremarkableness of Disobedient Desire, put on by the Lucie Drdova Gallery. Here you presented a series of “haute-couture” silk scarves imprinted with sexual motifs, playful faces or unchaste inscriptions such as symbols of the fetishization of the female body, power, fetish and phallic elements. Could you tell us more about how and why this series came about?

This series was created as an imprint of a time that I went through in a lover’s relationship. I could call it a relief of emotions, imprints that appeared within me. Now that some time has passed I can see how essential this relationship was for my personal development. At the time I was concerned with the theme of power, which relationships often have over us. I wondered how women are situated in society and this naturally led me to feminism and books where I searched for answers to my questions. The scarves were created as my hope that I and other women will break the staff of patriarchy which has historically been rooted within us. I decided to use scarves because they represent a luxurious item that men offer women in return for their company. These scarves however are given by women to women as a manifesto of sisterhood and solidarity. This work also opened up a new perspective for me on masculinity, which is just as fragile as femininity.

Has a transformation taken place in your case? What has helped you along your way? Do you have any idea what awaits you?

I think that I can call the last two years transformational, not only from the viewpoint of the general paradigm of changes in society, but also from an inner perspective. Taking time to stop and reflect, stays in nature and self education are essential in allowing one to withstand the storms moving our planet. Now I’m focusing on female sexuality which has led me to start writing poetry, something I am really enjoying at the moment.

Photo: archive National Gallery in Prague

I like the parallel of this work as it relates to the relationship between men and women in general. Even in today’s generation women must come to terms with the consequences of historical pressure and unhealthy relationships with men. Have you gone further with this motif in your work? How do you view the role of women and women artists in society today?

Relationships are like a mirror for me. They reflect society’s overall stance. It’s fascinating to observe and be able to work with this theme which, in my opinion, is inexhaustible. These days women are taking the reins. It’s a challenge that we should meet with the vision that the patriarchy has made its own mistakes which we should not repeat. Our task is to put aside the ego and see beyond the boundaries of one’s own gender. Collaboration is one possibility to healing the cracks of our civilization and giving it a chance of resuscitation.

As women, mothers, partners, etc. we should bring principles into society that connect matriarchy and patriarchy on an equal level. As an artist I sometimes feel like an endangered species that must simultaneously be incredibly resilient to survive. This requires a combination of a high level of sensitivity and introversion that must, at a certain moment, transform itself into extroversion in order for my work to be visible.

There’s a currently ongoing exhibition at the National Gallery in Prague as part of the Empathy Award. What can be seen at this exhibition? Did part of this series come about in New York? Could you tell us more?

This exhibition concerns itself with recycling and upcycling and it’s true that I had my first impulse towards it thanks to an artist residency in New York. When I visited the Material for the Arts Organization in 2018 I was overcome by the site and donation work. In my own practice I’ve always been very focused on materials and taken pleasure in discovering previously unknown ones, as I did during my stays in Korea and China. This project, which I worked on for two years, has combined my interest in fashion and creating my own collection out of unwanted material. In the installation you can also see my work environment. At the same time that the exhibition was opening in Prague, there was also an opening in the Below Grand Gallery, where I collaborated with the Berlinskej Model Gallery, that is with you and Richard Bakes. In this group exhibition entitled Holy Matter, I exhibited a latex top and latex panties from the latest works.

Photo: archive National Gallery in Prague

The exhibition State of Matter speaks to your fascination with material and upcycling. Now you’ve created your own physical and online platform as a way to house and explore this fascination. Could you tell us a bit more about that?

Yes, I’m currently preparing for the next step in my work, that is creating my own fashion label that’ll be on the border of art and design. Right now I’m working on an online platform that’ll be as user friendly and comprehensible as possible. One thing’s for certain, the name of the label will be “Votre Dick,” which was one of the central motifs of my scarves and the impulse behind continuing to explore this topic.

Most of your work is characterized by its use of upcycling materials. Is this an intention in which you battle yourself and the world or does it just happen naturally?

It comes naturally as a result of my own situation and sense of kindness towards my surroundings. I always consider the priorities when deciding what material to work with. I don’t want to continue to consume more and more things. I want the work that I do to alert others to the fact that we as humanity no longer have run out of time, which can’t be bought. By not recycling or surrounding ourselves with piles of garbage we only clog our own conscience by not acting with love towards nature or ourselves, becoming merely traumatized victims of our own existence.

Photo: archive National Gallery in Prague

This project is a good illustration of another level in your work, that is an interest in design and fashion. In this case, radical fashion. Could you explain this concept? Do you also practice radical fashion in your own closet? Tell us where you buy most of your pieces and which of them you like the most.

I try to keep my closet within parameters that I can oversee. I often think about fashion and what it means. Fashion is a reflection of the mental state, it is a communication with one’s surroundings and often makes up our first impression of a person, how they’ve fixed themselves up, what they’re wearing, etc. Radical fashion doesn’t cling to having plenty of everything. It’s about the feeling of being yourself in what you’re wearing, which is a part of your identity. It’s an expression I can articulate without speaking, just through what I’m wearing. The fact that I sew my own clothes is a way of communicating, telling the world outright what’s important to me. Most often I buy Camper shoes, Rains clothing and I adore the creative shoe company Simona Vanth and many others. In my own closet I prefer jumpsuits and kimonos with which you can create many variations and which are made up of surprising materials.

For more:

http://www.romanadrdova.com/

@romanadrdova

@lenkawallon

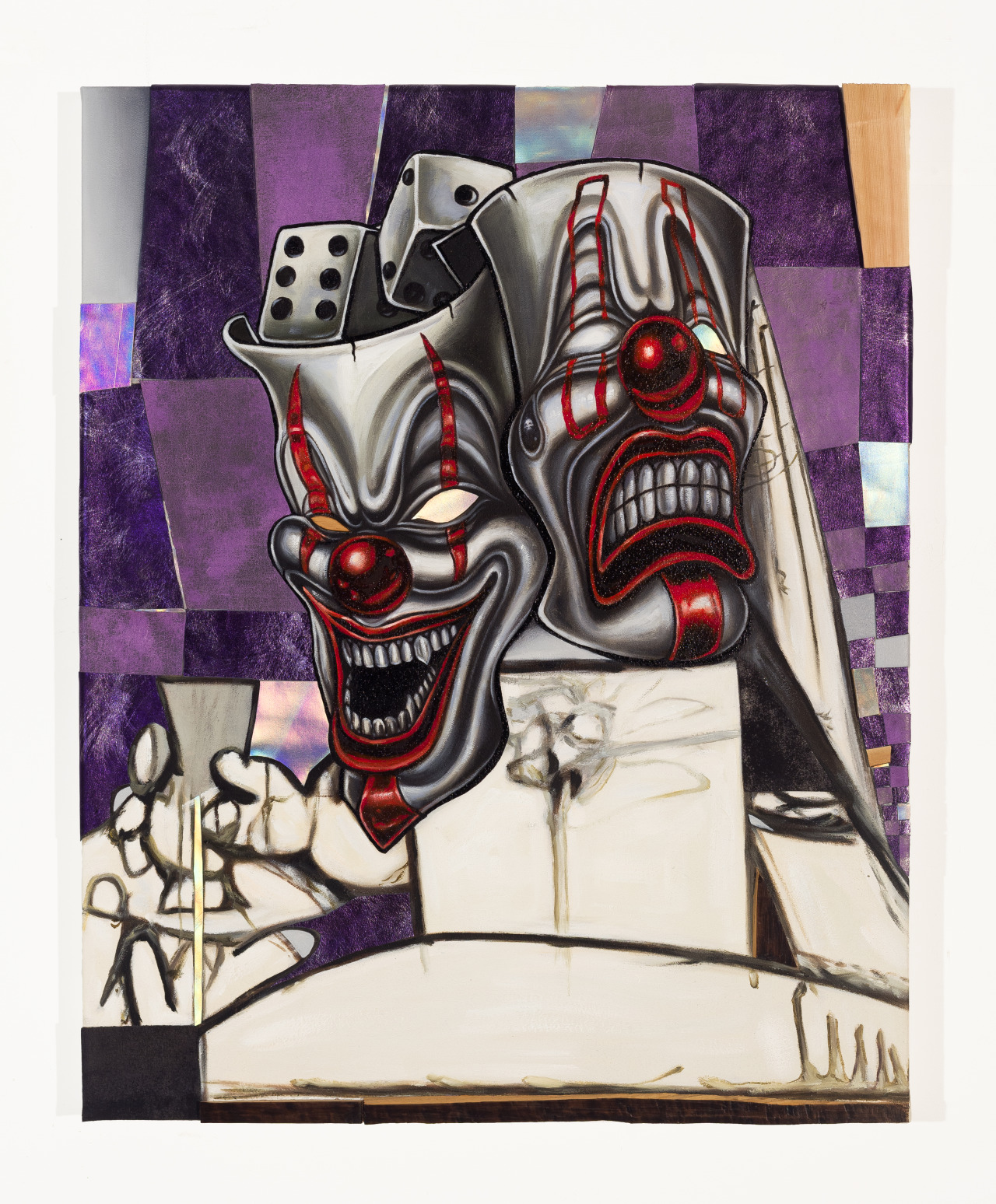

Edgar Serrano, I am an Enigma, Even to Myself, 2021, 48 x 72 inches, Oil on canvas

Edgar Serrano is a painter whose work integrates a range of visual aesthetics, iconography, and even materials, dissolving unstable borders between popular culture and fine art, analog and digital, self and “other,” while challenging xenophobia and reductive representation through appropriation and complexity. Born and raised in Chicago, he now lives and works in New Haven, CT where he earned an MFA in painting and printmaking from Yale University School of Art. His solo show Rumors of My Demise is the inaugural exhibition at Brief Histories’ new space on the Bowery in New York. Rumors of My Demise runs through January 8, 2022.

Interview by Brandon Johnson

Where are you from, where do you live now, and how has your environment affected your work?

I am originally from the west side of Chicago and lived there until 2008 when I went away to graduate school. After graduate school I lived in Brooklyn for a few years doing art residencies and trying to maintain a studio practice. The stimulating thing about Brooklyn was how everything was mixed up, different ethnicities, different cultures, different perspectives all interwoven and in tatters but beautiful, nonetheless. This is vastly different than the environment I grew up in Chicago where the city itself is designed to keep everyone segregated, isolated, and in place.

I currently live and work in New Haven, Connecticut. Connecticut is interesting because it prides itself in being socially progressive and inclusive environment. From my experience it’s also very segregated but in this invisible and unspoken way. I grew up amongst unseen but ever-present borders that have sharpened my senses and shape my practice. Looking into different worlds, either through art history, or Saturday morning cartoons, to wider political, economic, and societal issues I am drawn to the borders and peripheries dividing these worlds.

Edgar Serrano, Eternal Artifice, 2018, 46 x 61 inches, Oil on canvas

Could you speak on how these borders and peripheries manifest in your paintings, whether in terms process, form, and/or subject? For example works like “Eternal Artifice” appear to be in a moment of flux or transition…

Recently, I’ve been interested in the hand drawn “animation smear” which depicts one quick blur of motion in a single frame and the illusion of movement found in cartoons from the Golden Age of American Animation (1920s-60s). By using video editing software, I can analyze video files frame-by-frame, isolating and excavating normally invisible moments of transition or blur.

“Eternal Artifice” for example was initially excavated from various childhood cartoon sources using my personal archive of VHS tapes and video editing software. Resulting in images that are both familiar and strange, showing well-known cartoon characters in states of transition that are usually undetectable to the human eye. Due to the speed of film and the sequential duration of these short states of transition.

In my research I found that these in-between “blur or transitional” movements in cartoons from my childhood, mirrored my own trauma of not knowing English initially as the son of Mexican immigrants and that of migrant children in detention centers. The blur acting as a state of being caught in-between two realities, flux, or a limbo state. My relationship to these images is both symbolic and contains a dark narrative subtext.

A few of your paintings, such as “I am an Enigma, Even to Myself,” “The Sun Doesn’t Set It Just Goes Away,” and “Encyclopedia of Invisibility” include a Frankenstein-esque figure or silhouette. Is this a self-portrait of sorts? How do you relate to this misunderstood “monster”?

I sometimes evoke the tropes and aesthetics of villains and monsters as a metaphor for marginalized identities. Cartoon monsters as abstract representations of how people might perceive me or others that resemble me. For example, the werewolf, the intruder, or the Frankenstein monster, operate as proxies. The Frankenstein monster in particular is a monster with compassion and who also suffers from a complex identity. Feeling misunderstood, he causes fear due to his appearance, and that same fear makes him afraid. This sentiment is mirrored in the social realities of contemporary America: the fear of the unknown and xenophobia. As we know through great literature and perhaps in art, humanity’s irrational perceptions and fear are the true monsters.

In your younger years, your visual influences were cartoons, album covers, and magazines. Since entering the formal world of fine art, what have been your more recent visual influences?

I am still interested in imagery grounded in reproductions, like cartoons, postcards, and comics. But I am also clearly interested in and responding to the political and social context around me.

Some of my visual influences range from postwar/contemporary German artists who moved from abstraction to figuration in a new way like Gerhard Richter, Sigmar Polke, Albert Oehlen, and Georg Herold.

Recently I’ve also become attentive to the inadequacy of abstraction to clearly delineate meaning, which leaves room for a fresh perspective and to make new meaning. Some of the other artists that I see as exploring this territory are American abstract artists like Rochelle Feinstein, Mary Heilmann, and Jessica Stockholder. This inadequacy leaves the door open for invention and opportunity in painting, which appeals to me.

I am also invested in Carroll Dunham’s work. As I see it, he disregards the boundaries between high and low art and gathers diverse vocabularies into one picture frame to create immediacy and impact. Ideas and feelings come from one direction and social and political conditions come from another direction. I try to approach painting from a similarly messy hinge point.

Edgar Serrano, Old Brown and Jaded, 2021, 30 x 24 inches, Oil, leather, and wood on canvas

This hinge point is interesting in relation to some of your newer work, which incorporates pop cultural imagery based in Latinx culture, including photorealistic depictions of cholos, clowns, masks, and low-riders, with art historical references, abstract forms, and materials such scrap leather and wood. What is it about the dynamic between these elements that appeals to you?

We are all molded by our environment, more so when we are young. My early life seeps into the work. But I am not interested in replicating the conditions of my upbringing. Instead, I want to infuse these memories with my present self and contemporary issues. My hope is that these dichotomies of Latinx culture and art historical references that hinge in my lived experiences demonstrate my willingness to be open and vulnerable while also leaving room for subversion.

Regarding materiality, I use wood and leather to index a kind of Primitivism which I hope also subtly conveys issues of cultural power.

I am curious about the idea of Primitivism as it relates to Modernist Art that has appropriated artifacts, carvings, and images produced by ancient native cultures. Primitivism is of course a condescending term coined by so-called enlightened civilized Europeans to refer to the art of the “uneducated and uncivilized tribes of Africa and Latinx America.” The word Primitivism presupposes a lack of evolution in these cultures and the art that they produced.

I’ve been thinking about self-taught art as a kind of primitive mask that both obscures and refracts representations of the Latinx. The kind of contemporary “primitive” masks I am talking about can be found in stickers distributed in low-income communities via vending machines that are meant to appeal to young children. I am interested in how these images facilitate identity formation as these unflattering mass mediated images circulate stereotypes within and outside of Latinx culture. In contrast, my work attempts to use these images to construct subjects that contain their own complexities and agency.

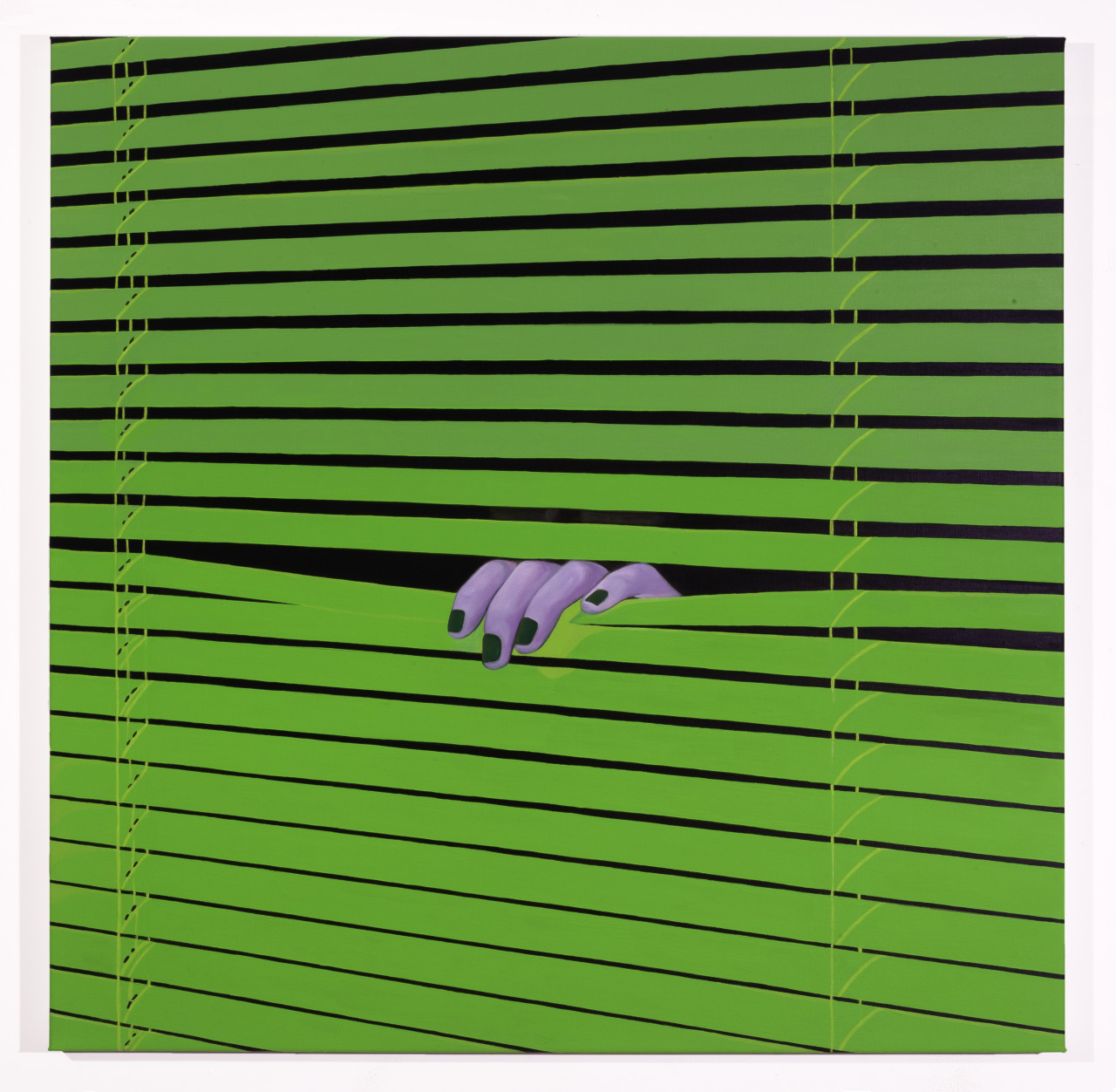

Edgar Serrano, Intruder IV, 2020, 36 x 36 inches, Oil on canvas

One of my favorite paintings (or series of paintings) in the show is “Intruder,” the first version of which appeared in your issue #25 zingmagazine project. What does this image of a hand pulling apart blinds signify to you? And why haven you chosen to make multiple versions of the painting?

For the “Intruder” series, I considered how the window has been used as a metaphor for painting: a transparent screen that offers a glimpse into another world. This series began with an image I found on the internet that I then digitally manipulated. Combining the metaphor of art as a window to the social imaginaries of xenophobia in contemporary America, the window also works as a metaphor for screen culture, translation, the flattening of information, and a border or boundary between worlds. I use the Internet as a window to an eternal present and intermediate space, separate from lived time; it offers me both a way to understand our present and a chance to see a future beyond oppressive traditions and hierarchies.

I also like to think of the window as a transitional space: It offers me both a way to understand our present and mirrors my own experience of existing in-between cultures as a Mexican American. I see the hands pulling apart blinds as abstract representations of humanity. Are we looking in or looking out?

The reason for the multiple versions is the limitless possibilities that are available by using digital image editing software. Also, my renewed interest or perhaps permission in seriality stems from recently reading, Van Gogh The Life by Steven Naifeh and Gregory White Smith and also The Andy Warhol Diaries. Both artists drew repeatedly from the same subject matter. Like a meme, this reliance on a single source opened the possibility to create endless and imaginative iterations from a single image.

Installation view, courtesy of Jack Hanley Gallery

“Margaret Lee: Summer Discutio” on view at Jack Hanley, East Hampton, August 27 – September 18, 2021

Interview by Devon Dikeou

The title of your show “Summer Discutio” seems to open up conversation—root of discutio is discussion, but “discutio” also finds itself akin to shattered, strike down, dissipate which are the opposite of discussion. Could you talk about how the title and the word discutio effects and affects the reading and making of this recent body of work.

I came across “discutio” while reading an older text, although funnily can’t remember where specifically. While prepping for this show, I found a note in an older sketchbook where I had written the word very large and circled it, which meant I should look into the meaning. And yes, while looking into the etymology, I saw this contradiction which confirmed my wanting to make my new work with this contradiction in mind. My move towards abstraction was spurred on by wanting to sit with contradictions or seemingly oppositional forces. Very simply starting with black and white, 2D and 3D not through a “verses” lens but a relational lens or a reciprocal relation.

There is a very pared down palette and material use in the four paintings and four sculpture groupings, black, white, silver, gray (paintings) and wood scraps, nails, and screws (sculptures). No jars or loose change, disbanded rubber bands—that junk drawer described in the press release is curated and edited to a minimal amount of variants . . . Please elucidate on these decisions.

The process of narrowing down my choices is generally how I get to making a new body of work. I’ve never been drawn to the “everything is possible” fantasy but do think if consideration and care are applied to the given parameters and context, most things are possible. Conditions are always changing and so things in the past might not apply to today, so before I start working I take an assessment. Looking through my jumble jars/drawers is a simple, highly controlled, low-stakes mental exercise in assessment. Rather than tossing the whole lot out at once or using it all at once, I dump it out and see if things start to click with the ideas I’m mulling over. In this case, it started with scrap wood. The off-cuts were already all the same size creating an instant grouping without me having to decide scale. The uniformity of those pieces of wood informed my decision to stay rigid in my pallet and material use. It is always a relief when the materials give directions so clearly.

Margaret Lee, Discutio #1 & 2, 2021, courtesy of Jack Hanley Gallery

Installation view, courtesy of Jack Hanley Gallery

Previous bodies of your work take on/cite artistic movements, trends, practices as varied as the Pictures Generation, Surrealism, outright trompe l’ouille, even collage. The work in “Summer Discutio” is more staid . . . I feel like it’s channeling some era, a summer era oft thought of in terms of the Hamptons, as so many ab ex or action painters called the Hamptons their studio/home. Did locale have any influence on the work exhibited . . .

It’s hard for me to separate the location from its history and from its present form and I have mixed feelings on both, as I’ve had mixed feelings about all the other movements/trends I’ve cited previously. There is so much romanticism around painting and especially painters who have left the city. That narrative often ignores or erases previous histories as well as privileges the singular genius mythology. When given the opportunity to exhibit my work in a very specific context that perhaps I’m not 100% comfortable existing within, the process of conceptualizing, honing down ideas and the actual making of the work helps. I don’t feel the need to make that extremely personal process explicitly legible within the works themselves but hopefully materiality, form, palette and repetition come together to convey not resolution but an expanded inquiry, which I hope continues indefinitely.

Margaret Lee, Zebra (Huh/What), 2009

So this idea of context in terms of studio practice and exhibition is of a personal nature, but there is some discussion/discutio that happens naturally between conception/execution and conception/exhibition . . . what about context when a work or body of work is collected. There an artist has no idea in what context their work will be exhibited or seen, or equally importantly, in the reading of their exhibition history present, past, and future. It’s an uncontrollable known, or maybe a controllable unknown. How does the work in “Summer Discutio“ relate to say specifically, the series in the Dikeou Collection, Zebra (Huh, What) 2009-12 . . .”

Those Zebra “paintings” are works I have consistently returned to as I make stretched paintings on canvas. I think when I made those works, I was trying to set certain parameters for how my work would be contextualized and what type of conversation the works would elicit. I wanted to question value and how it is created and the role of reproduction and authenticity within that process. The zebra acted as a ruse that allowed me to work with black and white paint without having to commit to or be placed within a Painting dialogue that I did not necessarily belong or wanted to be placed. Ten years later, I still committed to working with a limited and stark palate and less concerned with controlling context. Resigned and accepting discussion does not always result in understanding and consensus.

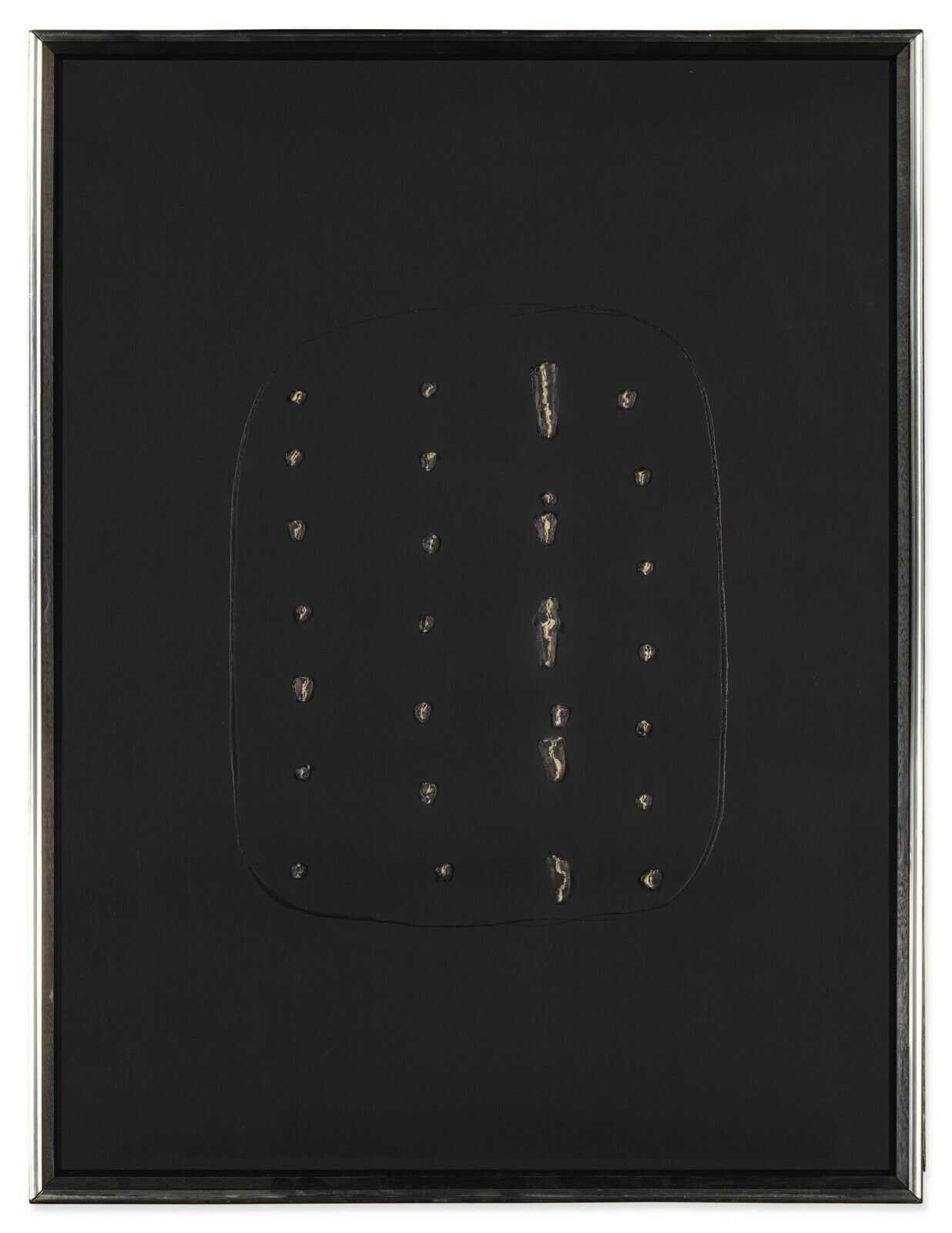

Lucio Fontana, Spatial Concept A (Concetto Spaziale A), 1968

Alberto Giacometti, City Square, 1948

Pedestals, well they aren’t really that are they, plinths would be more accurate. How do these plinths interface with the work . . . of “Summer Discutio”. A perfect exhibition structure to present the imperfect . . . I kinda want to see one of those nails break the plane of the surface of the plinth that presents it . . . The same goes for the white cube gallery, which seems to be a cottage, and has cottage like cut out walls that follow the pitch of the house rather than the scrutiny of the white cube . . . And one of the wall hangings is referred to as sculpture . . . Very “Working Space”/Frank Stella-ish . . . Oh and Fontana . . . Screws certainly pierce the picture plane there . . . Thoughts . . .

I wasn’t able to do a site visit to the space before making these works but once they sent me a floor plan and photos, I realized the space felt somewhat divided in two, rather than a traditional white cube. This probably led me to wanting to include pedestal works to help balance the proportions between wall space and floor space. Whether or not I was successful, my intention was to seamlessly transition from the 2D painting surface to the surface of the sculptures. The paintings sit on white walls so I wanted the small sculptures to sit on an equivalent, which to me meant white pedestals. I definitely was thinking about piercing the plane, which was more easily achieved via sculpture than painting. I’ve been thinking about holes, punctures and the objects that get placed in said holes or do the puncturing for a few years now. I guess I’m still thinking.

Numbers . . . Three and four . . . Do they have any significance . . . In “Summer Discutio” . . . The groupings of both paintings and sculptures literally are in groups of three or four, often the compositions themselves in the paintings and sculptures favor groupings of three or four . . . I think I even count three or four windows . . . It speaks certainly of rhythm and balance, sometimes symmetry . . . Sometimes asymmetry. Are these threes and fours lonely soldiers or walking Congress in palazzos . . . Discussing or Discutio . . .

When I number my works, I think it’s in the mindset of getting one foot in front of the other, slow and steady, one step at a time, don’t get ahead of yourself. In my earlier work, I could set myself a task of making a plaster form look exactly like a watermelon. It was very obvious when the work was done and if the transformation was successful. With abstraction, it’s such a battle knowing what I’m trying to achieve and also knowing if I’ve arrived at the place I think I was trying to get to. Start with #1 and seeing how far it goes allows me to work without setting an overly ambitious agenda or thinking in grand epic proportions. But also, yes in regard to being in relation to the windows, I try not to fight against the space where I’m to exhibit new work but to allow the space to inform my decisions. And yes also to this idea that the works are talking or in discussion with one another, especially the sculptures. There is an internal dialogue between all the objects in the space, with each other and with the environment. It would be impossible for me to transcribe into words all the back and forth that is going on but also maybe that’s not the point.

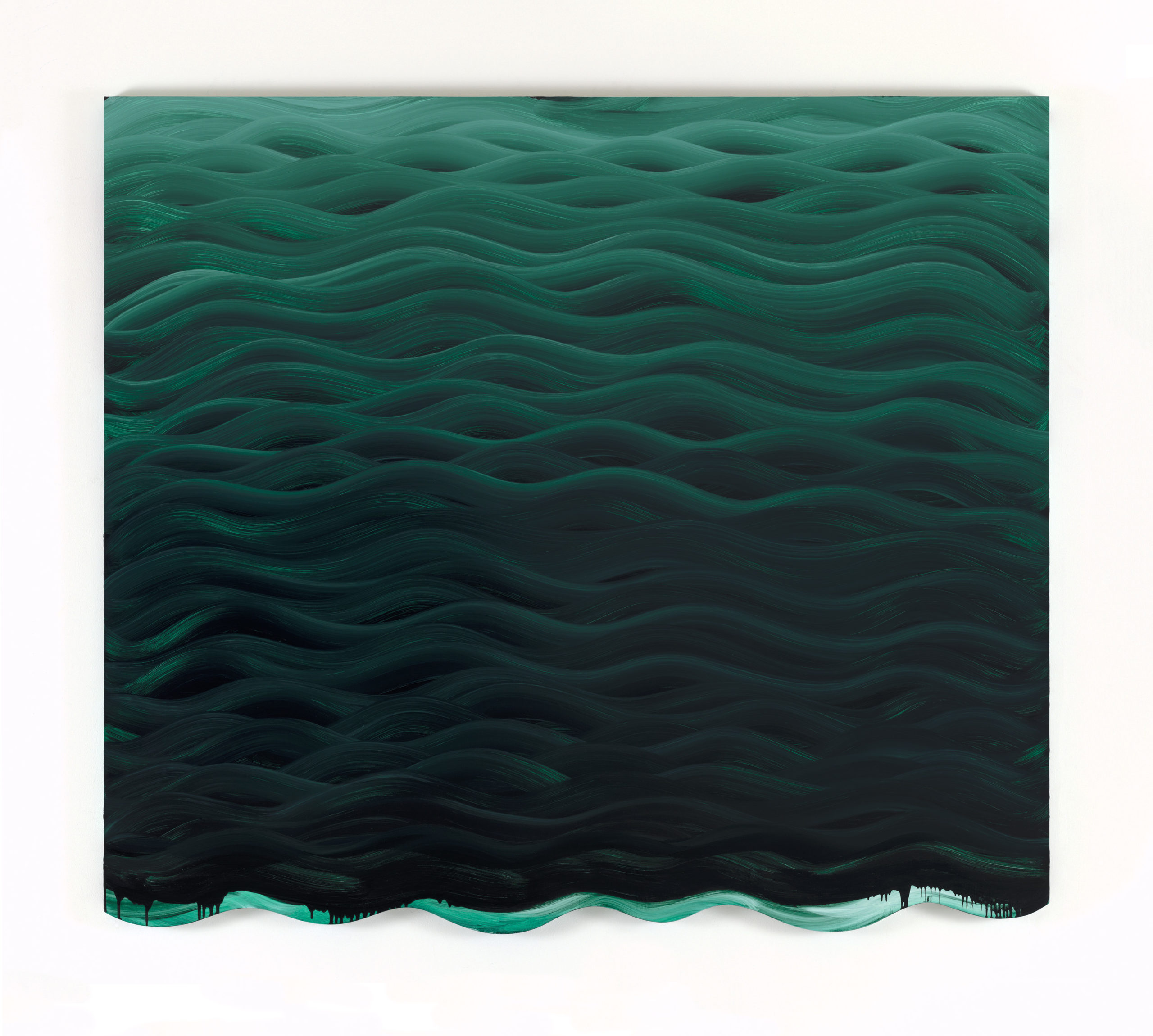

Karin Davie, While My Painting Gently Weeps no 2, 2019, oil on linen over shaped stretcher, 74 1/2 x 84 inches. Courtesy CHART, photo: Spike Mafford.

Karin Davie, originally from Toronto and now working between Seattle and New York, is a painter responding not only to the history of the practice preceding her time but also to her personal experience in the world. She was awarded the John Simon Guggenheim Fellowship Award in 2015 and was the subject of a major retrospective at the Albright-Knox Museum, Buffalo, in 2016, along with other institutional exhibitions both nationally and internationally. Her curated project

“Pushed, Pulled, Depleted & Duplicated” (with a poem-forward by John LeKay) appeared in issue #19 of zingmagazine. Davie’s solo exhibition “It’s A Wavy Wavy World” is on view through October 30 at Chart Gallery in Tribeca, New York.

Interview by Brandon Johnson

Upon entering the gallery I was met with two large scale paintings “While My Painting Gently Weeps No 2 & 4”. Each was immediately reminiscent of the surface of a moody and foreboding sea, which speaks to the title of this exhibition “It’s A Wavy Wavy World”. Did your thinking around the show change at all with the recent prolific flooding that occurred in New York as a result of the rainfall from Hurricane Ida?

The weather has become so unpredictable and dangerous because of global warming—but no, I didn’t think about this recent event in terms of my work. The imagery in these paintings comes from a deep ongoing interest in the history of art, the language of painting, issues of gender, identity, the body and landscape. My work doesn’t come from a reflexive reaction to something current in the news cycle. It’s a distillation of things that come from past and present history and my own lived experience. If I am drawn to some experience or idea, or am inspired to investigate something I don’t understand, these may develop enough urgency to make a painting. Things enter the work through a kind of osmosis. It’s filtered through my engagement with the world, sometimes pleasant, other times upsetting or enraging, and this takes time.

I currently live in Seattle, Washington. When I travel to my studio over a floating bridge which stretches across Lake Washington, I study the color and movement of the water and how it changes depending on the light and reflections. This experience of being surrounded by water, is an amazing sensation. I’m sure it has influenced my work. But I should also say, that water has an effect on me not only as an observed phenomenon, but as a metaphor for the forces of flow, unpredictability, transparency, the emotions, among others.

Moving further into the gallery there are four paintings featuring white squares in the middle surrounded by wavy brushstrokes and color gradients of blue, green, violet, orange and yellow. The former made me think of being underwater and looking to the surface light, while the latter resonated as cosmic or even supernatural transitory passageways, birth canals or “the light at the end of the tunnel.” Are these references on the mark, and how did you decide on the color palettes for these four paintings?

All the square paintings with intrusions have a slightly sly and humorous relationship to the metaphysical “light at the end of the tunnel” image. I wanted to play with this idea, and connect it to Minimalist painting, which is self-referential, emphasizing the medium and object-hood of the canvas, over a reflection of the outside world. These paintings push right up on representation and depictions of the body. This work is also rooted in personal experience, engaging with ideas about the self and identity. It’s a mash-up or smash up depending how you look at it (laugh). To me, they look like many things that convey transformation. For some paintings, I had a clear idea from the start what the color was going to be—certain hues of watery blues, hemoglobin reds or chlorella greens, for instance. I start by mixing up those colors, but the process allows for intuition. It’s not taken directly from observation or straight out of a tube. It may have origins from things I’ve observed in the world, and has to feel specific, but expands to involve organizing combinations of gradient colors to capture a mood or a feeling of temperature as well as creating optical movement, light and space in the painting.

In both cases, there is a primordial depth as relating to the sea (from which all life on our planet originates) and our own human watery origins of the womb. This is not only a space of physical abyss but also emotional, as watching the sea and contemplating our origins tends to have this effect. You’ve said the “wavy image” is a “recurring theme in my work and a metaphor for human emotions and life’s challenges–an obsession of mine.” Could you say more about this wavy image—as a symbol, a formal approach, and metaphor?

I can’t really tell you concretely why I’m compelled to paint waves or curving undulating forms, except to say that I’m driven to depict forms that relate to things in nature and the human figure. Geometric shapes contain and oppose this organic form. Perhaps we’ll find out in the future that these attractions or obsessions are all based on biology and genetics. Waves, by definition, are a disrupted transfer of energy and an action. The wave imagery can be metaphorical, but it’s not necessarily a thing itself, it becomes both a thing and an action when I paint. In my work an apparent landscape can morph into a bodily function or contour. It is this kind of “waviness” that is central to my expression. I’m engaged with the paint as a material and manipulate it into what I need to convey. My expression is embedded in the formal language of painting. In this particular work, it manifests in fields of wavy strokes in seemingly antagonistic relationship to the shaped format. It’s challenging and satisfying to work within this tight but limitless conceptual framework. These paintings have kinetic energy both optically and physically. These waves are essentially energy—they can destroy, or rejuvenate, possess darkness or light.

Karin Davie, In the Metabolic no 3, 2019 oil on linen over shaped stretcher 75 3/4 x 72 x 1/2 inches. Courtesy CHART, photo: Spike Mafford.

Many of the canvasses are shaped. What went into this decision? I’m particularly interested in those small semi-circle notches or extensions found at the bottoms of the In the Metabolic paintings…

When I first started this recent work, making wavelike marks around the inside edges of a large square, I observed my other hand securing the paper. I liked how the fingers appeared to become a part of the image, so the first drawings included a cut-out thumb shape intruding or protruding into the square. In both the drawings and paintings, the illusory image accommodates to the shape of the stretcher bar created by perverting the square. These first images led to other formal interventions determined by the shape and scale of different body parts or the canvases themselves. For instance, in the paintings “While My Painting Gently Weeps” and “Shape of a Fever” or “Down My Spine” the bottom or side shaped edges function like a cartooned version of the wavy strokes, which sets up a slight discontinuity. They purposely don’t exactly replicate each other’s form. In these works, the painted image is not co-extensive with the canvas shape, but is not unrelated to it either. It suggests a give and take of uneasy harmony with no easy answer over whether the literal or the pictorial has the upper hand.

The works on paper were made 10 years prior to the paintings. What led you to revisit and expand this body of work?

The large gouache drawings in the exhibition were made before the paintings, which is unusual for me. I don’t normally make comprehensive works on paper first. I see drawing and painting as conceptually linked but different enterprises. My process is that I make hundreds of doodles in sketchbooks, like automatic writing. Sometimes, I see an image in my mind, like hearing a song in your head, and then I quickly get it down as a doodle. If something interests me further from this process, then I will proceed to painting, sculpture, etc. But the paintings have a life of their own and everything still has to be worked out in the actual painting. This can take several years, as it did in this case. Things kept changing and shifting. It took a few years to settle on the scale and form. Although the gouache drawings in the show provided a foundation for these paintings, there were many steps in between. The materiality of oil paint differs from gouache, and the scale of the drawings differs from the paintings. This changes our physical interaction and perceptions about the image.