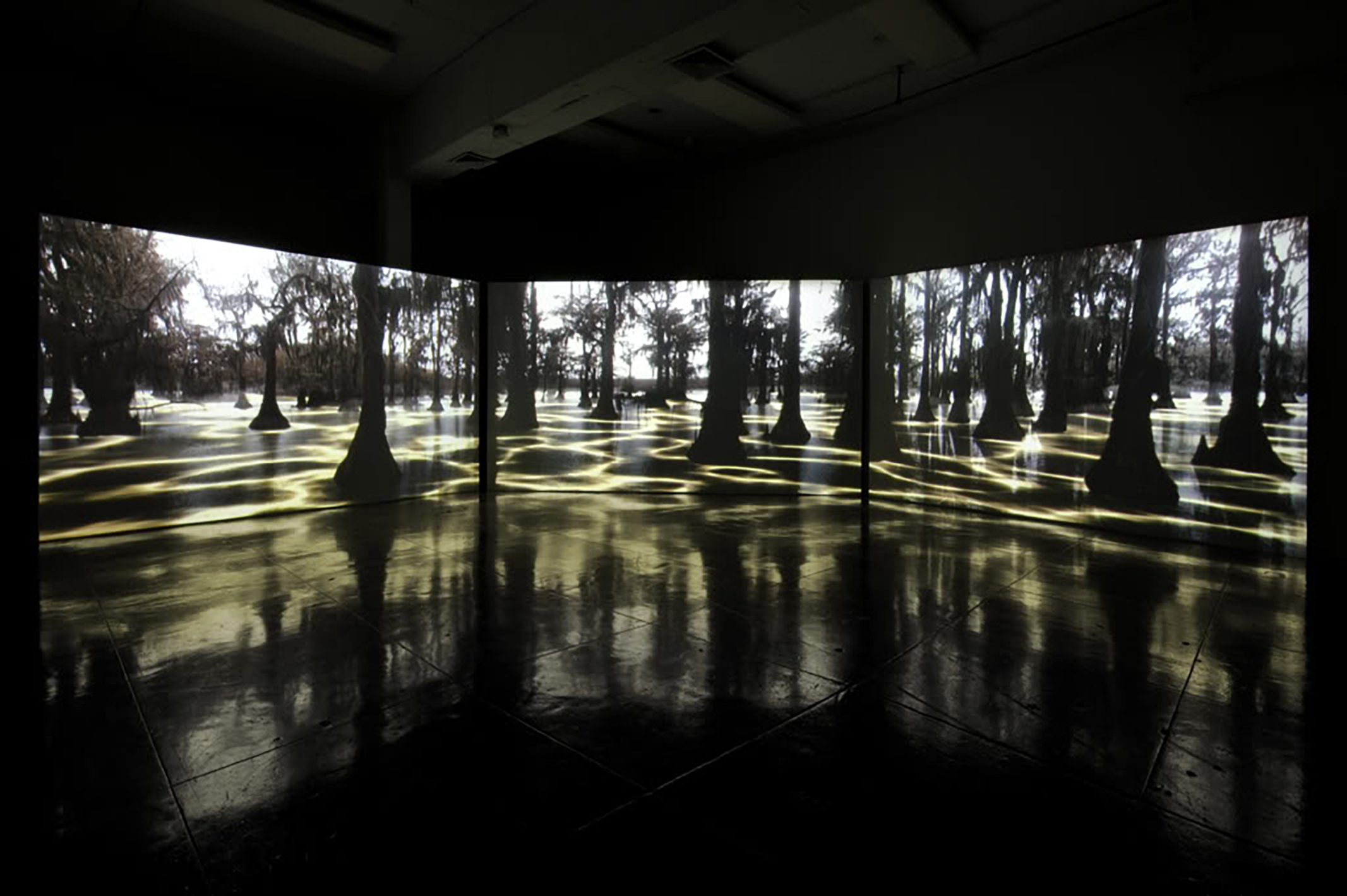

LEVIATHAN, 2011, three-channel high definition video, 20 minute loop.

Originally commissioned by Artpace, San Antonio

In the aftermath of a week with both a hurricane and an earthquake on the East Coast of US, and year in which, Japan has been devastated by an earthquake, a tsunami, and its Nuclear aftermath, and with a year of the most devastating oil spill in history, Kelly Richardson’s work has the relevancy and chilly methodology to wreak havoc on the otherwise still perceptions of her subject matter. She embraces a 19th century axiom—“The Apocalyptic Sublime”, with the precision that George Lucas first explored in his THX 1138 or the clever tautology of Ridley Scott’s Blade Runner. Her work captures fear, anxiety, resolution, beauty, mystery, omnipotence, awe, and desolation people feel in the presence of the unknown both in nature and in life. I had the pleasure of sharing a residency with Kelly Richardson at Artpace in San Antonio, curated by Heather Pesanti, and was initiated into the weird and luxurious sensation her video installations evoke. And now I have begun to look at the world through some different viewfinders, and like with all good art, wine, hallucinogens, or sex—after experiencing it—the world seems a little different, a little more fragile, and yet, a little more epic. What follows is our emailed Q&A, or “Come on Irene [sic]”.

Interview by Devon Dikeou

Terra Nullius, landscape work not touched by humans would seem to have a strange relationship to you and your work. You live in the UK—the ultimate non Terra Nullius landscape—it has been centuries being sullied, sculpted, terrorized, or tamed. And yet you try to find landscapes that might have any or all of these qualities in both hidden and obvious ways, and then you digitally create some effect—in effect a super Terra Nullius. Can you speak about this . . .

I’d say it’s increasingly true that the work focuses more and more on locations without signs of human interference. Occasionally, there are works which use manmade structures of some kind, but many of the ideas dictate using the Terra Nullius landscape. Most often, unplanned indicators of civilization inform the work in ways which don’t support what I’m after. If elements of sullied landscapes are present in anything I make, it’s deliberate; either it has been inserted digitally or selectively left in the shot to support the idea.

While majestic and beautiful, the work should also have an eerie, if not terrifying quality. If they function properly, the viewers feel consumed by the landscape, losing themselves in the work. If there are signs of a tamed landscape, the threat of the un-urbanised wild isn’t present which prevents fear of the potentially unknown.

Let’s talk about what Woody Allen calls, “Your early funny work”, and your early work is really funny, literally. Like the “Ferman Drive,” or “The Sequel,” much less the “Wagons Roll” . . . Humor, what are the advantages and disadvantages . . .

I used humor in the past as a way of inviting people into the work. From there I was hoping they would unpack it and end up feeling all sorts of other, often conflicting sensations. At some point though, I guess it was 2006, I decided that humor was far too specific. I’ve always tried to make ambiguous works where the viewer is unsure how to feel about it; it may be beautiful but at the same time unnerving (as above) and while humor is a great entry point, it ran of the risk of overshadowing what I was really after, the conflation of numerous ideas and interests which inspire a kind of contemporary sublime.

The Erudition, 2010, three-channel high definition video, 20 minute loop

This movement that you introduced me to, the “Apocalyptic Sublime,” pretty much sums up Edmund Burke’s idea of the sublime, “fearful joy.” But it really has some fascinating history and amazing relation to your work. Will you say something in relation to this.

The manifestation of apocalyptic art and its popularity came about during a period of domestic unrest, foreign wars and quite significantly–as it pertains to its relation to my work–anxieties towards major societal and environmental upheaval caused by the birth of the Industrial Revolution, which came to fruition around the same time. During the 18th century, interest in the Apocalyptic Sublime was expressed through what would have been ‘popular culture’ for the time: writing, poetry and art. Similarly, with widespread predictions of impending environmental meltdown as a direct result of the Industrial Revolution, during the last decade we’ve witnessed a return to imagery and stories depicting the Apocalypse with the film industry producing an unprecedented 50+ films illustrating various apocalyptic themes, many of which contain scenes which use similar techniques used by the painters in the 18th century to inspire the sublime.

Artists who were associated with the Apocalyptic Sublime envisioned catastrophic outcomes of this era, looking forward to what may be a result of the Industrial Revolution. We’re now sitting on the other side, facing its effect on the planet and ourselves. By way of the film industry, the Apocalyptic Sublime, or at least the popularity for consuming imagery depicting a catastrophe-ravaged planet has returned, almost certainly reflecting a like, collective anxiety towards a very uncertain future. My work plays into this, along with a number of other ideas and influences.

Ok the Creature From the Black Lagoon . . . it looooms in “Leviathan.” What is your worst nightmare?

I’ll share two actual nightmares that I’ve had which were equally terrifying. The first depicted the end of the world by way of an electrical storm. I was on a space station of some description, with the perfect vantage point to witness our planet being zapped with a wild web of blue electrical currents. The second, along a similar vein, involved the sun which ‘didn’t rise’. It was surprisingly peaceful and calm for a world which understood that it had hours left to live.

The Group of Seven. This is a hugely influential Canadian art group from the 1920s created what I imagine is a pretty hard body of work to deal with for a Contemporary Canadian artist working in what is seemingly the “landscape” genre. But you reference them quite naturally, or as a juxtaposition, unnaturally. Give us a clue into your thoughts on this . . .

As a Canadian artist it’s impossible to make work using landscapes without being part of that history. One of the interesting objectives of the Group of Seven was to showcase the beauty of the rugged, untamed Canadian landscape. I feel like I’m approaching things from the other side, after landscape–where I’m fabricating the wild, in a sense, to create a sensation of the sublime, which from my perspective has largely disappeared from the natural world. While I’m representing beautiful vistas like the Group of Seven, I’m also incorporating ideas about our experience and understanding of our highly mediated world where fact and fiction are barely decipherable and how we can no longer view landscape without being aware of how much we’ve drastically altered it, both physically and digitally.

Exiles of the Shattered Star, 2006, single channel high definition video, 30 minute loop

As a youngster from Colorado, of course I was privy to some of the most absolutely exquisite views in nature. In fact, one of those views, that of the Maroon Bells is perhaps one of the most downloaded screen savers in the world. So in fact, most people’s view of the famed mountain landscape is not a natural experience of the mountains, but a virtual one, that appears onscreen when activity on a computer has ceased. And according to Baudrillard “Simulacra” in a way means that the virtual experience at least equals, maybe excels, and perhaps exceeds the actual human experience. Do you think of your work as a critique of this or do you embrace it as a way of creating landscape terroristically, with our only tool left, digital manipulation?

I embrace digital manipulation as a tool to allude to the multiple, hybridized and seemingly un-navigable “realities” we now exist in. It’s not so much of a critique as it is acceptance. This is the world we live in; now what?

Which brings me to my last question. Often times when you make a piece, there is some type of Pilgrimage involved, like the Pilgrimage described in Michael Kimmelman’s Accidental Masterpiece chapter, “The Art of the Pilgrimage” in which the meaning of the Pilgrimage from Colmar to Marfa is elucidated upon. For you, traveling to places like Uncertain, Texas is just the beginning. You share the Pilgrimage with the viewer—a generous move as opposed artists whose work a viewer must/need to physically travel to, to see/view—like Smithson’s “Spiral Jetty,” Di Maria’s “Lighting Field,” or Judd’s “100 Aluminum Boxes.” How do you feel about bringing the Pilgrimage to the viewer as opposed to requiring the viewers’ dedication of time and effort in order to see the artwork/landscape in actuality . . .

That’s an interesting question. Most of the time I seem to be messing with pristine views which physically, I would never want to mess with. Working digitally also means that I can create impossible or improbable scenarios. I couldn’t transform the Lake District in England with raining meteorites, I don’t have the means of installing a vast field of holographic trees and with the most recent piece commissioned by Artpace, Leviathan, the phosphorescent life form in the water doesn’t exist.

Also, by removing location and all of the information associated with it which grounds perspective and understanding means that I can bring viewers into unfamiliar territory. I can transport people to another time, into possible futures or the distant past. In contrast to these strange, alternate spaces, I can ultimately make visible our current environment with some measure of hindsight.

Kelly Richardson’s work is currently on view in ‘The Cinema Effect: Illusion, Reality and the Moving Image’, Part 1: Dreams at Caixaforum, Barcelona, curated and organised by the Hirshhorn Museum and Sculpture Garden (through September 4, 2011) and ‘Videosphere: A New Generation’ at the Albright-Knox Art Gallery (through October 9, 2011). Please visit her website at www.kellyrichardson.net for further information on her work and upcoming exhibitions.

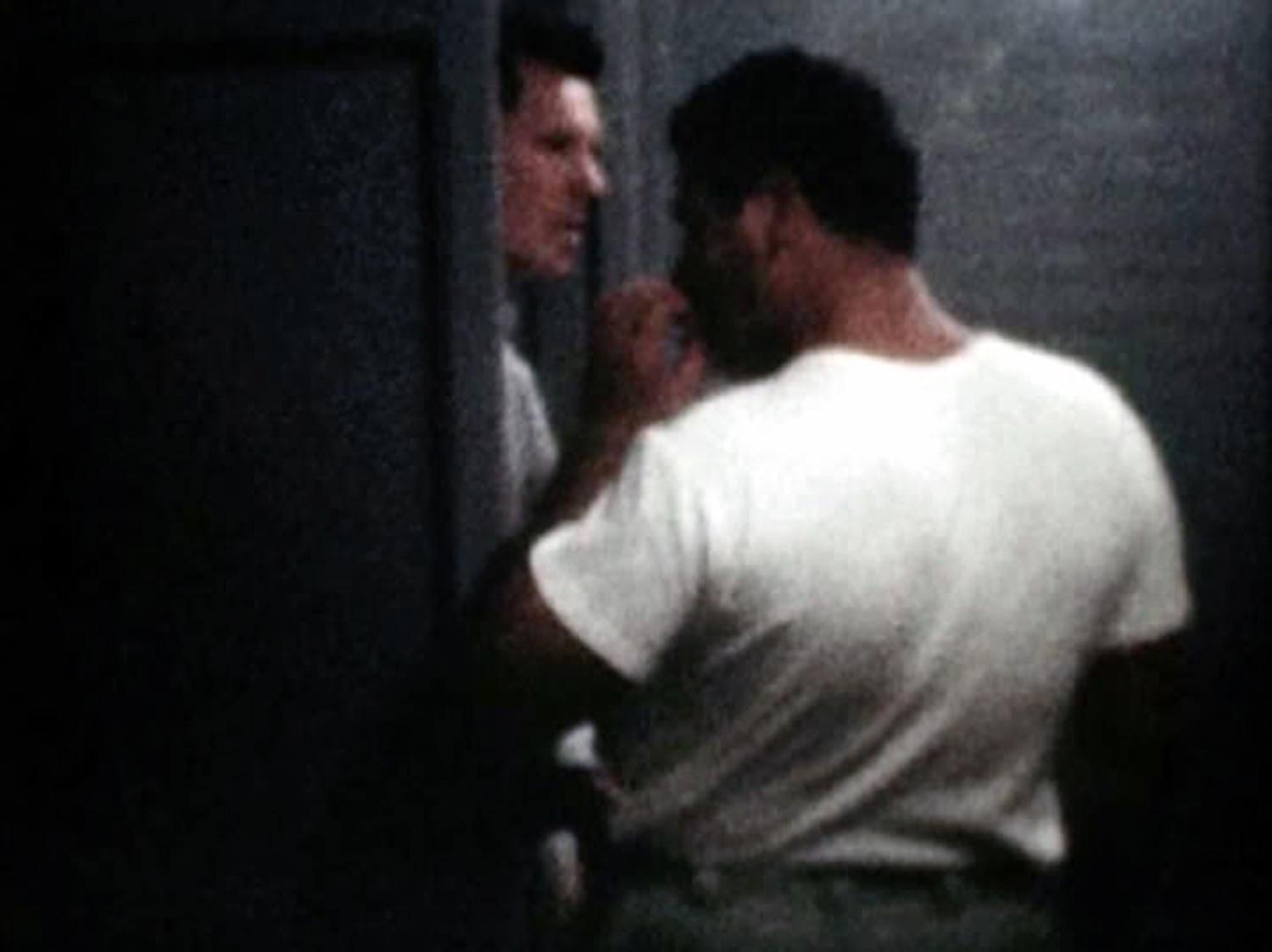

Still from Tearoom, 16 mm film transferred to video, color, silent, 56 minutes, 1962/2007

William E Jones was born and raised in Ohio, but is now one of LA’s leading independent filmmakers. I recently caught up with him about his highly emotive body of work, which predominantly deals with the deconstruction of artifice and façade in found footage; this has included gay pornography from post-Soviet states (The Fall of Communism as Seen in Gay Pornography), homophobic police training footage (Tearoom), and Cold War propaganda (Berlin Flash Frames). He recently exhibited in The Sculpture Center in Queens, and his work has otherwise been shown at museums and film festivals worldwide—including the Musée de Louvre, MoMA, the International Film Festival Rotterdam, Sundance Film Festival, and was the subject of a retrospective at Tate Modern.

Interview by Ashitha Nagesh

Just to begin, I’d like to say that I really love your work; it’s striking, without being explicit. Could you tell us a bit about your influences? What is your particular attraction to old war footage and gay pornography, two things that wouldn’t necessarily usually go together?

In the present era, war and pornography have more in common than may at first appear to be the case. US military personnel in the current theaters of war spend enormous amounts of time in isolated places where fraternization is very unlikely. Watching porn is a major pastime, and as the notorious photographs from Abu Ghraib revealed, there is some production of porn going on, too.

Since 1973, the US armed forces have not resorted to conscription, which, while scary for individual men during the Vietnam War, had the virtue of bringing together a range of classes in one social unit. Now the military is perceived as a vehicle of upward mobility for working class people, a perception that often proves to be illusory, or at best, immensely risky. This bitter reality seems to trouble those governing the United States (or at least their most hawkish elements) very little. They behave as though American working people are expendable, though perhaps not as expendable as the foreigners they are sent to bomb.

I suppose there was a time when pornography offered the promise of becoming a star, which is its own peculiar type of upward mobility. With the recent rise of bareback and amateur porn, and the virtual collapse of profitability of the adult video industry, pornography has become the realm of disposable people. Their bodies entertain us fleetingly; their fates generally do not concern us.

The act of repetition simultaneously fetishises and desensitizes the material for the viewer, and this can be seen in Film Montages (for Peter Roehr), and in Industry. What drew you to repetition? Do you feel that the act of repetition makes the non-explicit footage somehow explicit, in the Freudian sense of uncanny?

Strict repetition is a strategy almost alien to the cinema. It is absolutely fundamental to music (without it, there would be no rhythm) and rather common in modern art (as in Warhol, minimalism), yet seeing exactly the same thing over and over would never happen in a narrative film, which, we must acknowledge, is the dominant form of cinema. Peter Roehr appeals to me because he took up repetition with complete consistency, and applied it to his movies without moderating it or “cheating.” This bracing disregard for the rules of how to make a movie, at the risk of engaging in a kind of sadism, suggests one of the ways that film and art are still distinct as media. Filmmakers care that their works are watchable, because if spectators don’t stay in the theater for their movies, they won’t get to make any more of them. Artists tend to take a position of indifference on this question. Few have seen Empire in its entirety, but this hasn’t harmed Warhol’s status as an artist; it may actually have enhanced it.

This idea is especially poignant in your work The Fall of Communism as Seen in Gay Pornography—given that it seems to be about something far more personal than new capitalism and the commodification of sex. In fact, what I took from The Fall… was that it was particularly haunting, not only because of its recent cultural relevance, but because it evokes that feeling of strangeness, of finding one’s way in a completely new environment, navigating the unknown and being taken advantage of—which I think are feelings that most people can, at least partially, relate to. So, I found it interesting how this work was so personal, whilst also speaking of a wider political context. What was your thought process whilst working on this film?

From my own personal point of view, one poignant aspect of The Fall of Communism as Seen in Gay Pornography was that I had no money when I made it. I consider the collapse of state socialism in Eastern Europe the most important political event of our lifetimes. At the time it happened, I was living thousands of miles away and was not capable of recording anything directly. Yet the transformation of the way people lived was so profound that evidence was everywhere (as it still is, I would argue). It was just a matter of me finding this evidence and placing it in the proper context. Fortunately, I had the presence of mind to realize that I needed to look no further than the neighborhood video store.

Despite the efforts of a century of narrative cinema to make us believe otherwise, individuals rarely make history. We generally experience historical change as dislocation and confusion. This is the pathos of modernity: no matter how smart or secure we feel ourselves to be, our consciousness has trouble reckoning with new forms of domination and the latest crimes committed by managers of capital. At certain moments, the rules of the game are laid bare. I think The Fall of Communism as Seen in Gay Pornography contains a few of them.

In your recent work, Eyelines, you present found film footage of advertisements from the 60s and 70s and compile them, in order to distort and confuse the original intention of the images. The footage has naturally faded to various shades of red, and your contribution to this is mostly in the act of compilation. Similarly, when discussing Tearoom you have said that you ‘didn’t want to obscure the actions of the police by imposing your own decisions on the material’; how do you explain this move towards less-appropriated and more found footage?

Eyelines dismantles one of the fundamental figures of narrative filmmaking (a holdover from figurative painting), the eyeline, by looping very brief shots and alternating them in intervals so quick that the effect is stroboscopic. The work is reminiscent of the “structural” avant-garde films that analyzed the formal aspects of cinema, often at a microscopic level. Eyelines also has a mathematical, or perhaps musical, structure, as many of my works do, though this is rarely obvious. Every single permutation, that is to say every combination of individual frames, is exhausted over the course of Eyelines’ 1 hour and 51 minute length. Though the frames are not altered at all, I wouldn’t exactly call Eyelines a “found footage film.” For one thing, the total length of the source material is only approximately 30 seconds. The visual effects are achieved through montage, and as the piece plays out, the multitude of combinations invite spectators’ eyes to play tricks on them.

I had the pleasure of seeing Berlin Flash Frames at The Sculpture Center’s (NYC) recent exhibition ‘Time Again’. At the beginning of the film, the images are fast and obscure, before eventually slowing down to show more clearly the collapse of the actors’ and civilians’ assumed ‘camera face’ identities. What interests you about this? Why did you choose a slow revelation over an immediate one?

Immediate revelations are better suited to billboards and abstract paintings than to moving image works, which must unfold in time and have the possibility of justifying their duration.

There’s also a theme of disguise and acting, and the undoing of this, in your works that is prominent in The Fall…, Berlin Flash Frames, and even Tearoom. You seem to be fascinated by this idea of letting one’s guard down, captured in accidental footage of people caught in deeply intimate, unstaged and personal moments—it was therefore fitting to see you refer to Tearoom as ‘an historical artifact.’ So, in light of this and of your work with old wartime footage, such as with Berlin Flash Frames and War Planes, is the preservation and, perhaps, redefinition of history important to you? How do you view the relationship between documentary and propaganda—what in particular draws you to working with, and the deconstructing of, docustyle propaganda film footage, such as Berlin Flash Frames or Tearoom?

Propaganda films exploit the rhetoric of traditional documentary forms in order to commit a fraud. Documentary is not a style, but an ethical position the person representing takes toward the represented. In propaganda, ethics are of little concern.

The original material of Berlin Flash Frames interests me because it exhibits a diversity of approaches to filmmaking. Outright falsification employing actors on sets exists side by side with surveillance footage of the construction of the Berlin Wall, and there are other sequences that appear to be documentary footage, though they are not exactly that. An actor from the fictional scenes circulates among crowds of people waiting in line at government offices in West Berlin. Most of them were aware that they were being filmed, but there wasn’t much they could do about it, besides looking away (which preserved their anonymity) or looking directly into the camera (which ruined the take). I can extrapolate from this footage that every resident of West Berlin was a (willing or unwilling) extra in one giant Cold War movie.

Tearoom presents a different range of contradictions. The police force of Mansfield, Ohio (and the vigilantes that supported them) deemed it necessary to record surveillance footage of men having sex in the center of their city. The film was not shot automatically by a machine alone. A police officer had to stand for hours in a closet behind a two-way mirror watching men go in and out of a public toilet. He chose what to shoot: he turned the camera on and off, and within certain physical restrictions, he moved the camera. What was intended as an “objective” document of deviant sexual activity has come to seem transparently subjective. When an attractive young man enters the space, the camera moves frenetically, as though it cannot get enough of him. In the early 1960s, public opinion held the men in the film to be perverts and those who commissioned, shot, and used the film as evidence in court to be fine, upstanding citizens. Today, spectators are likely to form another opinion. Tearoom allows an audience to reflect upon this historical transformation.

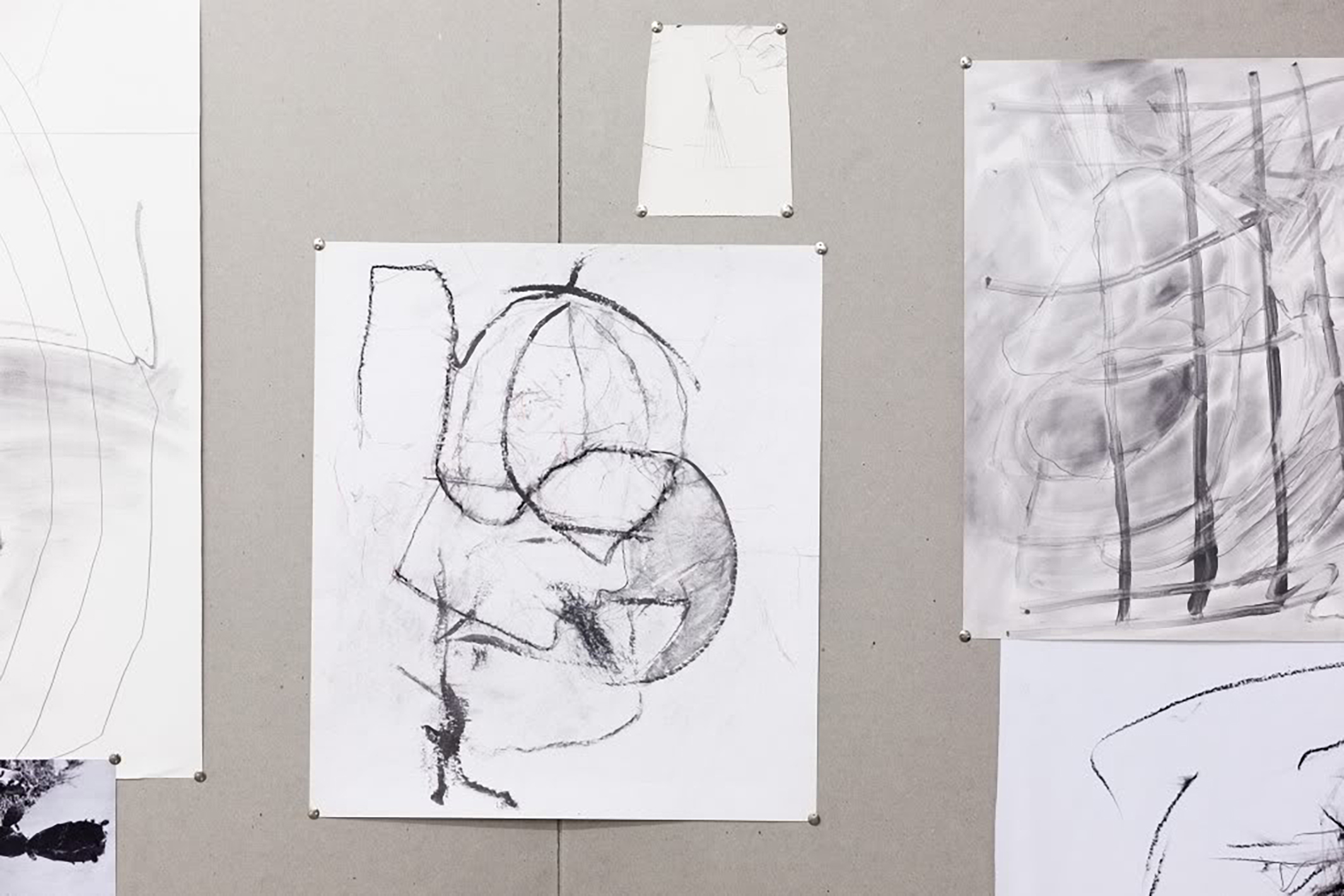

Untitled with Paperweights, 2011, mixed media, dimensions variable

J Parker Valentine’s work whispers: but her whispers exude cackles of thunder. Installations made of drawings negotiate a special place between the practices of both traditional works on paper and works of installation and object making. And in doing so they challenge the way these practices support and reinforce each other. The “drawings” are unrolled, cover one another, lean, are attached and weighed down, rest on other objects including tables—walls themselves are surfaces to be reckoned with, and drawings are even regenerated from other projects. These drawings in situ create assemblages of much larger presences that envelope, engross, charge, and frequent the space they inhabit—installing themselves in and around the viewer and the space. This flurry of quiet activity challenges gravity, loudly announcing a different language while demurely allowing for a different voice. We exchanged emails . . . Here is what transpired.

Interview by Devon Dikeou

Frank Stella’s On Painting makes a case that his “literal painting” is “pictorial”—that the physicality of the work has little to do with anything but the sum of its “pictorial” existence. Whether these aims are achieved in his work or not, I think it a useful way to approach your work. You make drawings that “literally” invade the realms of sculpture and installation, even performance. Will you speak about this . . .

I do see what he’s claiming as one way to perceive something. I’m also working in this intersection between physical form and image. For me it is often between drawn lines and the physical linear forms created by simple planar structures—for example the curve or bend in a piece of paper, or the angle of a panel. However, I’m trying to bring attention to the opposite of his case—that the physicality can’t be ignored, and a sculptural experience can and often does coincide with an image-based one. In my work, the three-dimensionality typically arises out of the process of making the drawings, more than as a point to be made.

Speaking of performance, one thing I find most interesting in your work is what you don’t show, the drawings that are hidden, the installations that seem interrupted, the gestures the viewer has to guess at, and those edited and not shown. How does this kind of performative improvisation process come about, studio to exhibition?

In the same way that frames are edited out of a film, some of my drawings are hidden. The difference is—you can see that I am hiding something from you—this is a sculptural property that creates a performative relationship between us. In the same way that I use erasure in my drawings to create an image, the blatant covering of an image with another creates yet another image. There is a recurrent push and pull of additive and subtractive processes.

The end product is often a palimpsest that reveals the evidence of time and action. Everything is improvised because the structure is based on discovery.

Untitled, 2010, metal, graphite, chalk, MDF

The materials themselves are often mined from previous works of yours and/or are recycled. This practice in turn creates a funny Nietzschian “eternal recurrence” in your work, each work exists as part of several works, both past and future. Will you speak about recurrence, eternal or otherwise, and the use of recycling as a strategy and a medium . . .

As I approach an art object as a problem, there are often many potential solutions to resolve that problem. If the artist has anything, it is the authority to make a decision on the resolution/non-resolution of a work. I am very interested in the poignancy of this decision.

When something leaves my hands, it’s finished and it’s frozen in time in its determined orientation, but if it has not yet left, I can continue to look for alternative solutions. This can be by combining it with something else. This might give the work an unfinished character—an openness to resolve, hence my interest in abstraction, which by nature, is open.

As I work on drawings, I photograph them. I collect these images in a folder on my laptop whether the works are finished or not. There is no apparent organization to this—something might be photographed once or many times in it’s process and nothing is labeled. There is really no delineation between separate works, there is no “right way up,” and the hierarchy is obscured between “good” and “bad.” This is not to say that I don’t choose particular successful drawings out of many to exhibit, but looking back at these photos and seeing how they relate from one to the next helps me to learn what a successful drawing might be.

I’m A-OK with fate. There is nothing precious with how I treat my objects. If my cat bites into a sculpture, fantastic. I often travel with a tube of rolled drawings. The edges do not stay clean, they don’t lay flat, the drawings have rubbed off onto each other and this is usually how I display them.

The way Mondrian used black & white as color—because of the sharp juxtaposition to the primary colors in his compositions—or how Impressionist palette was based on the juxtaposition of one color playing off the presence of another—is useful to think about in relation to your use of color. You use the intrinsic materials’ colors and juxtapose slight differences and nuances between and among them to create and achieve similar color connections/juxtapositions. What is the role or how do they, materials and color assemble, create, and dance through your compositions/installations?

Limiting myself to the intrinsic colors of materials allows for less “work” and thus more immediacy.

In certain ways, I think about image and color along the same lines. For example a found image of, say, a sunset, is similar to found piece of yellow fabric in the way that I do not need to draw or recreate that sunset or paint the color yellow, because they already exist. For me, drawing is not about recreating something, it is about finding something. The use of a particular image or color would most likely be due to the fact that I found it (or photographed it myself), kept it around me for a while, re-looking at it over time, and finding an importance in it, and thus a juxtaposition most likely to something I have drawn.

I’m very attracted to color brown of the mdf panels I use and the richness of graphite against it. Graphite is reflective and depending on the light or from what angle you look at a panel, it can look black against the brown, or silver and hard to see. The dichotomy between image and material is one of many in my work—the archetype being that I constantly look for form, while at the same time avoiding it.

It is as if you undertake drawing, and its intrinsic limits, and screw with all the Big Wigs that began to screw with drawing in the first place. Serra, Twombly, Tuttle make drawings by way of their final product, be it sculpture, painting, or installation, and in doing so, dismantle our traditional notion of what drawing holds. You make drawing scenarios—sculptures, installations—that use the implicit practices that drawing encompasses. At the same time you negate the essential rules associated with drawing and in the process create a new definition of drawing by way of installation and sculpture. Please give us your thoughts about this . . .

Yes, I think I do make drawing scenarios. In art school, I had no real interest in any prescribed issues, so I decided to create my own. I found that I needed constraints to work off of, and I found these in the intrinsic limits of drawing and drawing materials. Also, I have a strong interest in time-based media but wasn’t content solely dealing with the consistent technical problems of film and video and looked for more basic materials that could allow me to explore a shifting image with more flexibility.

My drawings naturally moved into the realm of sculpture when I started drawing on MDF panels. The panels had to be constantly moved around, cut down, and stacked particularly for a lack of space. The activity was physical and so were the materials. There is a sculptural property to the way I make the drawings (adding and subtracting), to the drawn images themselves, and furthermore in the presentation of them.

Untitled, 2010, detail of installation view, Supportico Lopez, Berlin

The use of found objects, like the paper weights in your work (Untitled with Paperweights) at AMOA . . . they both function literally holding down drawings and visually becoming reflective mirror orbs, compounding the space and the visual and literal implications by their presence. Luis Barragan, the Mexican architect, used mirrored orbs in a similar way. What are the architectonics of your installations and especially the found objects, like the orbs?

My structures are set up to create intersections and associations between drawings. Their relation to the architecture of the room is primarily one of support, but also to create an active viewer that necessarily has to move to see things.

The reflective mirrored paperweights acted in the same way a body of water might act in a landscape, expanding and manipulating the visual space and drawn environment. But I also chose to use them for the contrast between the near perfect reflective forms and the povera-type materials.

You also use gravity to express the architectonics, in the way you lean an MDF Board against a wall (Untitled 2010) or balance drawings on work horses (Untitled with Paperweights 2011). Can you speak about the role of gravity in your work?

I use gravity as an intrinsic material, like others that you mention earlier. It always works perfectly, its symmetrical. It’s the glue of our world.

What’s on the horizon?

Right now I’m working on a book of drawings in collaboration with Peep-Hole Milan to be published by Mousse Publishing, and a solo show next spring at Lisa Cooley.

1664 Sundays, Diana Shpungin, 2011

photo: Etienne Frossard

Diana Shpungin was born in Riga, Latvia, in what was then the Soviet Union, but has since lived in Moscow, Vienna, Rome and New York City, her current location. I caught up with her about her latest exhibition, (Untitled) Portrait of Dad (Stephan Stoyanov Gallery, May 22 – July 3 2011)—a show that was simultaneously a memorial to her deceased father, and a wider, metaphysical exploration of death.

Interview by Ashitha Nagesh

The title of your recent exhibition, (Untitled) Portrait of Dad, refers unambiguously to the portraiture work of the late Félix González-Torres. How strong would you say his influence has been upon your work?

Yes indeed, the reference was a consciously direct one to one of my favorite works, Félix González-Torres’s “Untitled (Portrait of Dad)”. I changed the placement of the parenthesis, shifting the emphasis to read “(Untitled) Portrait of Dad”. The titles of the specific works in the exhibition are all so very particular that I wanted the overarching title of the show to be more general and open ended, but also making my admiration for González-Torres known. The title, as general as it is, encompassed everything I wanted to say and reference.

The show of course is influenced by the work, life, death and “after death” of my father, but I also look at it as a respectful nod to the life and work of González-Torres. While my father had a profound influence on me personally, González-Torres had a profound affect on how I look at and approach artmaking. In a way, this show was the first time I allowed myself to really explore that correlation so directly.

I have always been an enthusiast of minimalism but González-Torres took it to a new place and fused it with the personal. He was able, with a small thoughtful gesture and with seemingly flawless decision-making, to key into a sublime something so powerful and significant. An artwork (an inanimate object) that is able to communicate a gesture that resonates with myself and so many others. His work is both personal and political, but it does not scream at you, it speaks softly, it can engage you deeply if you give it the time. It is in the subtlety of the poetic gesture where I think the strength in his work lies and brings out an empathetic quality in me that few works have before or since. It is that elusive feeling I am after with my works, that sensation, that intangible something . . .

This quote by Félix González-Torres has always resonated with me, and I often cite it when I asked why I am an artist, I especially like the “good purpose” part:

“Above all else, it is about leaving a mark that I existed: I was here. I was hungry. I was defeated. I was happy. I was sad. I was in love. I was afraid. I was hopeful. I had an idea and I had a good purpose and that’s why I made works of art.”

— Félix González-Torres

Your entire body of works, from your earlier video piece from the end of the earth to bring you my love to your most recent pieces in (Untitled), seem to be preoccupied with time and the inevitable limitations of it. González-Torres once said, “Time is something that scares me…”. How would you describe your own relationship with time? Is it something that scares or inspires you? Or both?

I am not absolutely sure if “time scares me.” Existence sometimes confuses me, but perhaps that is a comparable thing? Time is necessary, time is a given and time is enigmatic, that much I know.

But I also think time is relevant, sometimes events seem to go by so fast, other times they last what seems to be forever. I suppose when we fear something time creeps up on us more quickly. The notion of time being both so ambiguous and finite is definitely scary (especially if you think about it for too long). I think whenever you are surrounded by illness and the possibility of death; time is certainly at its scariest. This perhaps in varied ways González-Torres and I have in common.

The limitations of time stem in our great desire yet failed ability to pause and control it at our whim. I certainly have not found a way to pause time yet (other than in my work) so perhaps that is one reason why I make art and in that sense time inspires me. The work is the only place where I can at least metaphorically fuck with time. Whether that be by conceptual reference, physical process or merging time and space as video can so often poignantly do.

Your pieces explore the relationship between time and distance—focusing both on the finite and infinite aspects of both. In from the end of the earth to bring you my love, distance is a tangible, measurable thing— ‘the end of the earth’ being a physical place on the map—whilst time seems to be on a constant loop, sunrise—sunset—sunrise—sunset, and so on, all over the world. In contrast, your more recent works seem to invert this; I Especially Love You When You Are Sleeping and A Fixed Space Reserved for the Haunting, for example, highlight the limited nature of our time, along with the immeasurable possibilities of space—metaphysically speaking. What influenced this inversion? Was there a change in perspective for you?

Absolutely, the work surely encompasses time and space in varied ways; concrete physical remoteness, emotional detachment, and the intangible metaphysical void. There was no change in perspective or specific inversion between the pieces—more specifically the methods used relate to the specific conceptual content and subjects tackled within each of the works. Both are about types of longing and intangibilities, loss vs. love, the dead vs. the living etc . . .

From an ongoing series entitled “The Geographic Fates”, the dual channel video work “From The End Of The Earth To Bring You My Love” is about communication, human relationships, love, desire and the enormity of what we know and experience. I wanted to take the conventionally beautiful symbol of the sunset/sunrise and find a kind of truth in it. Two people being in two precise points, as far away as achievable from one another on earth, would still be able to communicate by ways of our natural world without the interference of technology—a sort of grand, yet simple gesture if you will.

The works in “(Untitled) Portrait of Dad” also relate to time and distance but in this instance examining ideas of death, mourning and memory. The intangibility of death is often explained by means of religion in various cultures and death is often depicted in war films or in the media as remote and impersonal, in horror films as gloomy, morose or campy. I wanted to explore this without delving into the specificity of religion, or focusing on the cold, morbid or stereotypically “dark” depictions we are familiar with and I did not want to avoid the known reality of death, glazing it over to make myself or the viewer comfortable. Instead I utilized personal familiarity, cultural mores and taboos, with a dash of the supernatural and superstitious.

The sculpture “I Especially Love You When You Are Sleeping” relates to a phrase my father spoke to me on many occasions, however I chose the phrase for the work because in an ironic manner it speaks of our inability to speak ill of the dead due to cultural appropriateness. When you are “sleeping” (or dead) I especially love you—a life is glamorized, we speak only of the good times, obituaries and eulogies seldom contain a disapproving word. We often have a selective memory of those we lose.

I am interested in what encompasses our “known” time on earth. And with the understanding that I probably will not find out more than the average human, my work is counter-productively trying to attain this knowledge anyway.

I found 1664 Sundays very interesting; it highlights the relative shortness, and the limitations of our shared experiences. Considering the personal nature of the subject, how did you feel whilst constructing this work?

The title “1664 Sundays” refers to the amount of Sundays my father and I lived in common, from my date of birth to his death. When I calculated the days, it certainly seemed like an alarmingly short amount of time. So yes, by summing it up in a succinct figure, the lack of time we have alive and/or together with another person is relatively limited, are days literally numbered. Our experiences with people can be fleeting. The memory is all that can be sustained, although that can be fractured, selective or relatively hazy.

In “1664 Sundays” the viewers receiving of the recipe bag and taking of potatoes referenced González-Torres piles and stacks. With González-Torres it is like taking from the body itself, with “1664 Sundays” the potato pile references more of a burial mound, but of living things that keep growing and have the possibility of survival. The pile becomes a memorial to a story, a shared overlap of time and experience and a particular place in history. And if one so chooses they can take the potatoes home with them and cook my father’s recipe—again counter-productively reliving an experience in a secluded intangible way. The work always maintains this peculiar condition of longing.

1664 Sundays both reduces this shared experience of time to something mundane and everyday, and simultaneously invests this ordinary object (the potato) with a deeply personal significance. In a way, it is attempting to physically represent something that goes beyond human visualization—time spent with loved ones. What does the potato signify for you? Is it a purely personal symbol of your father’s potato recipe and potato-selling on the USSR black market, or is it a wider comment on Soviet culture and its own subsequent death?

Much of my work can have varied layered, cyclical, dualistic and serendipitous connotations. I love how one object can hold several meanings, some even contradictory, some seemingly non-connected but actually linked by way of an odd coincidence or fate if you will. In this case, the personal, the art historical and the politically and geographically historical.

That being said, the potato is emblematic of a number of functions. The potato was a bonding symbol between my father and I, by way of his potato recipe he cooked for me both as a child and when I would visit him as an adult. It was the only thing I would eat that he prepared, and it was how we found common ground.

The potato also relates to my father’s story-telling (a dying act in itself) of the “old country” and of his trading fifteen tons of potatoes for his first car, a Soviet made Volga. The potato behaves as an icon of that time period of black market culture, my father used the potato akin to currency, the story indicative of a time and place far away, only directly familiar to a relative few left among the living.

And lastly, the potato had strong significance in not just Soviet times, but to this day in Russian (and much of Eastern European) culture. A diet staple often referred to as “second bread”, it has sustained many people during grain shortages in very difficult times.

Being born in a country under Soviet Rule, it was difficult to grasp the enormity of what that life was like then because of my young age. My family immigrated to the United States when I was about four years old so my memories are really based in my fathers story telling, family albums and old books we had around the home. The linkage of ideas goes through a type of hand me down translation. Again, it took me utilizing the potato recipe (a very personal ordinary thing) to get down to the inherent political significance in that common food source.

Could you explain the meaning of the chair in A Fixed Space Reserved for the Haunting? Does it have personal significance, or a wider symbolism?

I really consider my work to have both personal significance and a wider symbolism. Of course much of my work comes from deeply personal themes, but these themes are also very universal. I translate my experiences visually by finding formal elements and signifiers that may have more open ended and relatable content to others.

Regarding the personal, I am really interested in what we as a culture or society deem to be “personal” or even “too personal”. I always find it hard to really delve into a subject unless it becomes real and tangible for me. For example, I, as many, could easily glaze over and become numb to the convention within media, like the monotonous repetition of a newscast, a tragedy summed up in a CNN news crawl for example. Until a story is told in a personal empathetic way it is hard to grasp the reality of a situation.

Regarding the sculpture “A Fixed Space Reserved For The Haunting”, my father was a physician and would repair items around the home with the means of his profession—domestic objects like chairs, tables, lamps, rugs, walls and also trees in the garden.

This chair is left empty and with one leg broken signifying the lack of repair due a person’s loss. So the chair is not repaired or “fixed” as the title suggests, but rather “fixed” in space awaiting an implausible return. The chair no longer functions for the living – one would fall if they sat down and would be stained by the graphite pencil which is methodically hand coated over the entire surface. The use of graphite pencil in my work functions a bit like a ghost in itself, an impermanent medium, the prospect of erasure always evident.

Importantly, the sculpture and the title stem from one of many family superstitions of having a guest or loved one sit briefly in a chair before departing a home so they will surely return safely again. My father had me do this whenever I would visit his house. After doing some recent research I found the superstition has gone through many varied/morphed versions, but all are rooted in Eastern European culture from Pre-Christian times.

In A Fixed Space…, by blanking out the personal details from the obituaries you generalize death, which seems to contradict the rest of the exhibition, which is a very personal and specific exploration of grief. Was this your intention? Could you tell us a bit more about why you chose to do this?

Yes, underneath the chair sits a stack of New York Times obituaries with pertinent information methodically censored; -all names, dates, places etc. have been blacked out, the stack wrapped akin to a cast relating to my fathers methods in medicine. The stack although formally looks like it might be holding up the chair, is not upon closer inspection (another way of suggesting longing through the formal tension).

With the partial concealment of the obituaries, what you end up getting is this very generic, humdrum commemoration that can apply to almost anyone. Once more, yes the show is rooted in the personal, but it all speaks of the cultural ways we do or do not handle death. The chair in “A Fixed Space Reserved For The Haunting” was metaphorically made for my father, but it could certainly be related to anyone whom has passed.

Much like “I Especially Love You When You Are Sleeping”, another aspect of “A Fixed Space Reserved For The Haunting” is the notion of selective memory (or maybe just selective public sharing) when it comes to death and separation. It was worthy of noting that in all of the many hundreds if not thousands of obituaries I read, not a one had a negative word to say about any of the deceased. As a whole, I was not interested in presenting an all-out sentimental memorial of my father with this exhibition, rather simply using my experience with his death as the catalyst to getting a minute bit closer to understanding what it is that mortality and memory really is and how it functions.

Sara Veglahn is the author of Another Random Heart (Letter Machine Editions, 2009), Closed Histories (Noemi Press, 2008), and Falling Forward (Braincase, 2003). She has taught creative writing and literature at the University of Massachusetts-Amherst, the University of Denver, and Naropa University, and currently lives in Denver, Colorado.

Interview by Rachel Cole Dalamangas

In a couple of your works, I’ve noticed the recurrent theme of drowning and I think when I saw you read at Burnt Toast in Boulder a couple years ago, you mentioned something about the narrator of a prose you were working on being obsessed with “deep water.” It seems water is frequently mesmerizing, but dangerous when it appears in your proses. Given the ghostly selves that haunt the words, I can’t help but think of Narcissus. But the narrators also aren’t self-obsessive; if anything they’re masochistic, absenting, breathy—sort of like if Narcissus and Echo had had water obsessed phantom children together. How does water relate to subjectivity as this tension occurs in your work? Why the obsession with drowning?

My obsession with drowning and deep water and rivers is borne directly out of my experience growing up near the upper Mississippi River—a dangerous, swirling, mysterious, muddy place that was always claiming people. The frequency of people falling into the river and drowning, and the rather nonplussed attitude of everyone about it (“oh, someone drowned…well, anyway…”) was always so strange and troubling to me. Plus, there was the added element of my own lack of swimming skills and a very early experience in a swimming pool where I had to be rescued by the lifeguard. And I am obsessed with rivers—that river in particular, but all rivers, too. They move, They have a place to go, they don’t have a choice, they’re traversed. You have to know how to read a river in order to stay out of trouble on a boat. Currents and the way the weeds flow and wing dams and so much that’s hidden. There are people who know that part of the river as well as they know their own family—and they do use the term “read” but I suspect they may not think of it as analogus to language or fiction. It’s all very real. Especially if you end up stuck on a sandbar in a storm. On a more metaphorical and psychological level, I suppose the obsession with water, and the element of danger that is inherent in a deep, muddy river, is related to the unknown, uncertainty, all that’s hidden, and how we make sense of the unknown.

One thing that I find extremely pleasurable about reading your work is how nice the paragraphs always look on the page. They’re given all this breathing room. They’re like slices of charm cake. They contain these constellations of disparate things: peacocks, zoos, swimming pools, maps, ladies. How do paragraphs operate for you? I would say your prose feels like it goes sentence to sentence, but it’s the field of the paragraph I always remember afterward.

My unit of composition is definitely the sentence, but I’m glad to know my paragraphs offer a completeness.

You’ve done some collaborations with poets and I may be mistaken, but I believe your focus was poetry at Amherst, where you did your MFA. Why the switch to prose at DU? It’s always sort of a silly question, but one I am forever intrigued by because it doesn’t really have an answer that can be universally applied. What’s the difference, for you, between poetry and prose?

Yes, I did focus on poetry at UMass—and though I did make my attempts with lineation, the majority of the poetry I wrote during that time was prose poetry. So I was always working with and interested in the sentence. Studying and writing poetry gave me a good training in the use of juxtaposition and understatement and image and musicality, something I may have been reluctant to try in fiction had I not had the experience of working with all of those elements when making poems. For a long time I avoided prose and narrative because I thought I couldn’t do it. I only realized I could when it became clear that it didn’t have to resemble something else, and it could (and probably should) look different than, say, a New Yorker story.

Because of my background in the poetic realm, my work tends to often be classified as poetry, although I don’t think of it as such. I’m often asked to defend why what I write is fiction (‘what makes this fiction?’ many have asked me, often with a tone of ire). And while there are certainly fundamental differences between poetry and prose, I think the focus on genre tends to limit one’s reading of a work. It can be dangerous, too, to declare something fiction or nonfiction or poetry—if it doesn’t adhere to the traditional tenets of the genres, then readers tend to dismiss it as weird or difficult. And then, of course, there’s the “experimental” label, which can also be a limiting description—especially as “experiment” implies something unfinished or tossed off, something that certainly can’t or shouldn’t be taken seriously. Yet, it’s the most convenient and encompassing term—a sort of short hand—so I understand why it’s used. But it does ghettoize the work, diminishes it in way. It seems odd to me that a lot of readers resist the idea that a text arrives at the form it needs. I suppose it’s the fear of the unfamiliar. I’m not sure the other arts have this conundrum or difficulty. Perhaps it’s because the material is language as opposed to paint or notes or light. I suppose language is hard to separate as a material because we also use it to survive in the world.

There’s a lot of musicality to the prose. It’s not eccentric rhythmically; but the words echo against each other, the placement of syllables seems deliberate. The thoughts don’t always transition in content, but almost always flow euphonically. Do you have any background in music? What sort of music do you listen to and does it impact how you play with language?

I do have a background in music, albeit a limited one. Even though I studied classical music throughout my early schooling and also briefly in college, I never felt I could become good at it. But it did give me a technical background into rhythm and, I think, maybe, how one might approach simultaneity via language (an impossible task, but one I keep trying to accomplish anyway). I think I may always be subconsciously trying to evoke the kind of fleeting emotion that only music can provide—it’s so fleeting, but it’s also so imbedded (for example, I almost always wake up with a song or melody in my head). And I love all kinds of music—classical and punk and opera and old country and and strange sound collages. I tend to listen to a lot of different things, but I also can be obsessive and will listen to a particular album or song over and over. But I need complete silence to write. I am too easily distracted by melody and lyrics.

There’s a razor-sharp clarity to your work. I notice that the texture in your proses seem to do some things that are very much major aspects of realism genre and just as often, things that are the total inverse of realism. For example, like realism, there’s this extreme precision at work; and unlike realism, there’s no attempt to be naturalistic or fulfill expectations about representation. Where do these worlds you write come from? Are they dreamt? Meditated? Whispered? Listened into? Do you know them before you write them?

I never know the world before it arrives. Some are dreamed, I know, but they get transformed in the telling and in the combining, so I can’t say I lift them directly from something known, so to speak. That said, dream logic is very important and I privilege the way a remarkable event in a dream is experienced as commonplace—every thing makes sense in a dream while we’re dreaming it—it’s only upon thinking about it or telling someone else where it becomes strange, unreal, and, also, it’s when we begin to forget it. I think I’m always trying to work with that element of fleetingness and the many versions of reality we all create, dreamed or not.

So much of your work is about dreaming or dying or dreaming after dying and about a state of consciousness that is transfixed, absorbent, mid-reverie. But the prose does the opposite to me when I read: it keeps me aware that I am reading. Every word is so important. The gaps between the sentences are like precipices between thoughts. My consciousness has to stay focused. So there’s this exciting tension there of watching a dream unfold while having to keep one’s mind en pointe. Where would you place the state of consciousness that is reading? It’s not really like watching a movie, though prose narrative and film are frequently compared. Do you think of reading as being hypnotized? As dreaming?

To me, reading and writing are so similar—there’s a level of action and agency involved with both. But reading, of course, is more something that one takes in, where writing, I think, is something that one gives out. The pulling together of ideas and images, though seems quite similar on both sides.

The temporality of your works is always very strange. It’s atemporal work, I think. Or rather, there is temporality, but it’s over and gone in a fragment of a sentence. Whole histories happen in a few words. Things disappear. There’s vanishing points and things following a longing into the distance. Then it takes whole stretches of a paragraph to look through a window, to follow the flight of a wreaking ball. But there’s always a voice that is leftover that keeps interrogating, describing, cataloguing. There’s both this posture of repose and yet, when I really follow things, there is the suggestion of a terrifying idea of how the universe is arranged. What is your fascination with disappearance?

I suppose this fascination with disappearance is related, again, to the river and deep water, but also to the way in which everyone’s existence is so tenuous. The cataloguing and interrogative elements are a way to keep track, to claim space, to say, “I was here.” And time is just strange! An hour can seem like a minute or like an entire day, depending. All of this is quite terrifying to me, and I think, again, the element of organizing and keeping a space for small things that might not seem important helps to assuage the horror of the chaos of life (which I realize sounds a bit dramatic…).

What other work from you do we have to look forward to?

I recently finished a novel, The Mayflies, which has had the privilege of being excerpted in some wonderful journals. And I’m currently working on a new novel, The Ladies. While not a sequel per se, it is a related book as The Ladies were characters in the previous novel. There have also been some excerpts of this work in progress published in some wonderful places as well.

Read an excerpt from Sara’s The Ladies here: http://www.zingmagazine.com/VeglahnTheLadiesExcerpt.pdf