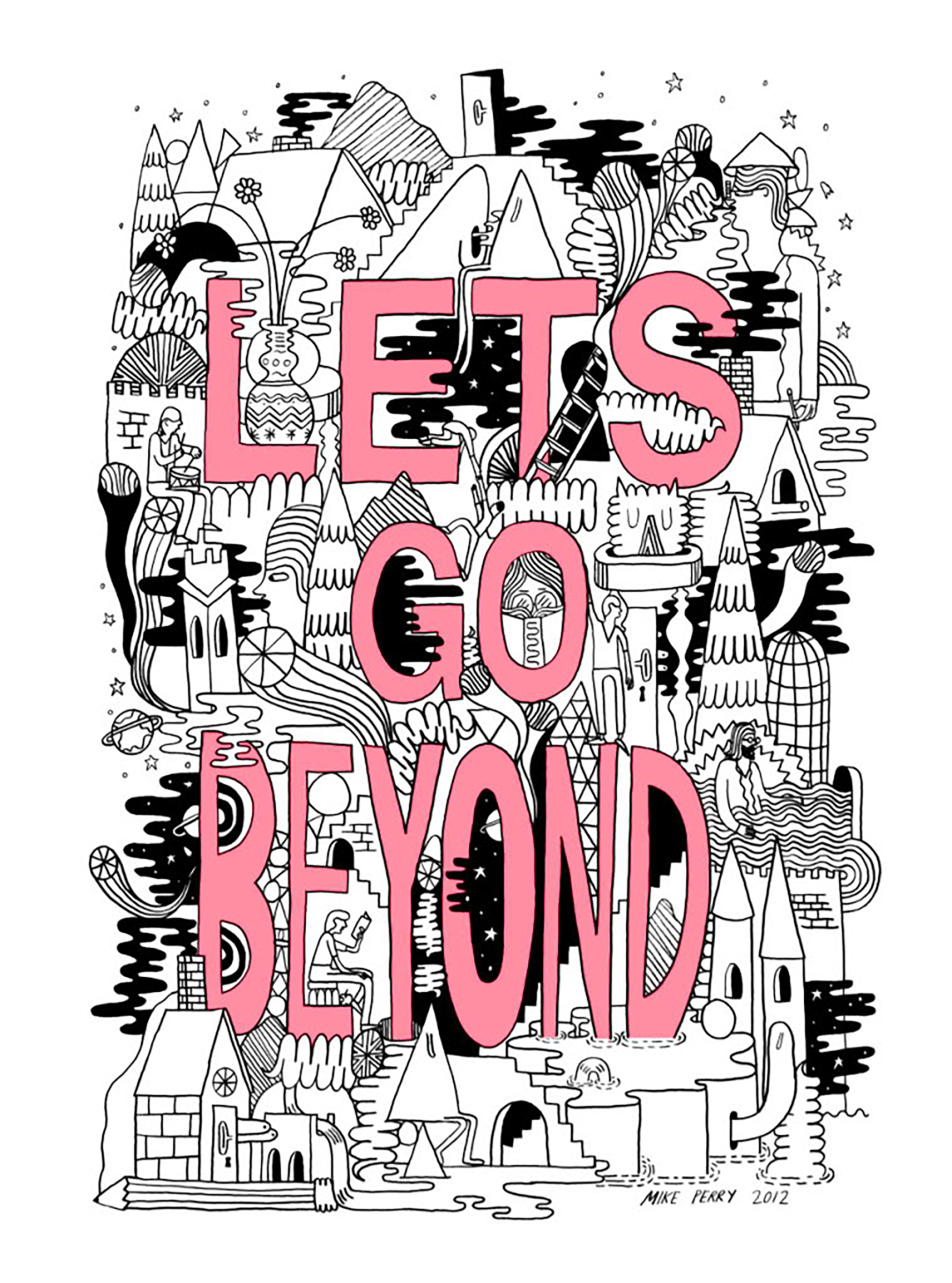

You may’ve seen Brooklyn-based designer and artist Mike Perry ’s work around. He has exhibited throughout the world and has worked for a variety of clients, including Urban Outfitters, The New York Times, Apple, Nike, Zoo York, and Target, to name a few. He has also published four different books on screen-printing, hand-drawn type and patterns, and—most recently—Wandering Around Wondering, a collection of his work so far. With an emphasis on hand-drawn and the “transformative power of making things,” Perry’s work is incredibly distinct and full of character. His work often deals with patterns, shapes, and anthropomorphic objects that join together to create a greater whole—and a glimpse into the mind of the man himself. Recently, I had the opportunity to check out Mike Perry’s studio and sit down to chat with him about everything from personal process to figuring out the universe (sort of). If you happen to be in Ohio, you can also check out the exhibit “Night and Day” at the Yes Gallery, featuring new work by Perry and artist Naomi Reis. It runs through July 20th, 2012.

Interview by Jessica Butler

Before getting into graphic design, you used to paint significantly in your teens. Does this background in painting have a role in your work now?

I would assume it does. The more I think about my work from the past, so much of it has been about getting these ideas out—an obsessive desire to create something all the time. So many of my hours are spent thinking of ideas or pulling a pencil across a sheet of paper. This always works well for me in a graphic design sense because deadlines are short and I would need to generate a lot of process before committing to a final outcome. The work I make now vs. the work then is so different. I was painting a lot of figures, a lot of portraits; things were very moody and my painting work now is getting more and more abstract. I was obsessed with John Singer Sargent then and now I find more comfort in someone like Alexander Calder.

It has been a great journey so far. This is my favorite part about being alive. Seeing what I used to make and how it turned into what I make now. Seeing the progress and the process. To me, some of the most exciting pushes in my work came from those stumbling accidents and my desire to look back at them and learn from them.

How did your time at Minneapolis College of Art and Design shape your trajectory?

My opinion about higher education has diminished over the years. That said, I got everything I needed to get and it was so brilliant. I was so lucky. Surrounded by so many amazing and inspiring people. Most of my education didn’t happen in the 9-5 of class time but in the hidden after hours in the studios talking shit, listening to music, and being surrounded by people in a place of ultimate creative freedom. As you get older it’s harder to be able to sit around and just make. I miss the sounds of someone running through the doors laughing. The screams of someone’s computer crashing and him or her not saving. The late night walks to the coffee shop before it closes to sneak in a little more caffeine. Within all of that was passionate, obsessive, powerful, abstract, fun, beautiful, creation.

Developing one’s own style can be a long, and sometimes difficult process for many artists. When do you think you reached the point where you felt you had “your own style?” What process goes into getting to this point?

Style is or can be a funny thing. I hope that everyone comes to their own style on their own. There is a way that your mind works in relation to your hand. Which works in relation to the world you were born into. And in relation to when you where born and the things you have seen, experienced, the tragedies, the comedies . . . This is your style. When I put my pencil on a sheet of paper it has everything I have been through, making its way out. It is who I am. This is my style. This is how you develop a style. You live life. If I hurt my finger or wrist then my drawings are different, if I am in the country with nature, this affects my work. Take it all in and be yourself.

Do you ever feel a sense of “comfort” or security in what you’re creating because of this seemingly established and unique style?

I guess maybe style is like finding your self. Which if you look at it like that, finding a style as a journey makes sense. I would say I do feel comfort. I am at a place where I feel both comfortable with making things that are unpredicted and just flow out, but also the ability to make things exactly like I vision them. I spent a lot of time trying to figure out how to make the work I wanted to make. Seeing the disconnect between brain and hand. It has been a growth experience and an adaptation to my hand’s ability.

You’ve worked for a variety of different clients throughout your career and have acknowledged the importance of business. Does your artistic integrity ever feel at risk?

I hope not. It would be a bummer for people to decide my work is not artistically valid because I needed to make a living.

I guess what I mean is, since you have a lot of different clients asking for a variety of things specific to their brand/business, do you ever feel like you need to change your style slightly in order to satisfy the client? If so, how do you deal with this and manage to stay true to your personal style and work?

It kind of depends on what kind of hat I am wearing for that project. A lot of the time people hire me to make something that looks like my work. In that case I just do my thing and hope they like it. But when it’s a problem-solving environment I like to explore and make according to the brief. I love the exploration part of making. I often give myself briefs to follow because I love visual problem solving.

A lot of your work contains similar patterns, images, and symbols. When we spoke you called it something like a visual “vocabulary.” How do you think these occurred? Is this idea of repetition something you encounter elsewhere in your life?

I think this vocabulary has been there the whole time. It was just the process of putting the book together that really opened my eyes to how much it is a part of the work. My guess is that most creative people have a lot of repetition in their work. These are shapes, ideas, colors that make us feel good. There are shapes and colors that when I use them I just feel good. Feeling positive about something you’re making can cause you to want to make more.

In our studio visit you also mentioned you’re a bit of a science guy and showed me an incredible sketchbook full of pages attempting to solve a cosmic problem you had in your head. Would you say the universe is a theme you gravitate towards? What sort of significance does the universe and science have for you?

I love the science fiction of the universe—that anything is possible if you can imagine it. It feels freeing and comfortable. I often feel like I am building little universes and placing planets and stars in their cosmic formation. I love that it is a great unknown but we understand the elements that have formed this greatness. Like the color red is an atom in a drawing I am making.

Are there any other themes, ideas, or sources of inspiration that you are especially drawn to?

Heritage, the future’s relationship to the past, the difference between silence and chaos (I try to work with this a lot. How to make something filled with chaos feel silent.) Organic vs. Geometric.

What role do words play in your work?

Words are very important to me. A lot of my ideas start as words. A quick one liner jotted in my notebook that comes out as two men playing tug of war. But then the opposite happens where I will draw a little face that turns into a poem. I love writing poems. I am trying to feel better about sharing those poems but it’s hard. I often hid poems in the work.

What’s something that makes you laugh or smile?

I just watched the new 21 jump street movie. I laughed a lot.

Finally, what can we expect from you next?

Isn’t that the question? I have a lot of ideas. Not sure what will happen in what order. Some books, exhibitions, maybe a few years of silence. Who knows!

Courtesy of Eleni Sikelianos

Poet, Eleni Sikelianos was raised in California and currently teaches at the University of Denver and Naropa University. She is a descendent of the Nobel Prize in Literature nominee, Angelos Sikelianos, as well as the niece of distinguished “Outrider” poet and scholar, Anne Waldman. She is the author of The Book of Jon (City Lights Publishers, 2004), The California Poem (Coffee House Press, 2004), Earliest Worlds (2001), The Book of Tendons (1997), and To Speak While Dreaming (1993). She has received numerous awards and fellowships, including a Fulbright Fellowship and a National Endowment for the Arts Fellowship.

Her most recent collection, Body Clock (Coffee House Press, 2008), is a benevolent, reaching linguistic exploration of time as contained in the body. Taking the subject of pregnancy as a center from which to chart seconds, minutes, quantum fields, wars, New York, death, god, dreams, fictions, and cells—to name a handful from the multitude of objects and thoughts in the pages of Body Clock—the work both summons and welcomes Eva, Sikelianos’s child with novelist Laird Hunt, into the world. As gleeful as melancholic and as sharp as free-flowing, the poems of Body Clock assemble richly tangible spheres of little and large universes that encase the reader in vivid shapes and extremities of time.

Interview by Rachel Cole Dalamangas

Body Clock is a work that seeks to unfold a language of time as a sensual experience of both the flesh and the mind. Thus, these poems slip between and overlay planes of experience, histories of universes, and platforms of perception, operating on adapted techniques of the New York and Surrealist schools of poetry. Additionally, Ovid’s epic, Metamorphoses, appropriately seems to be referenced frequently as a record of transformation(s). I was dazed by this kaleidoscopic, expanding and contracting world of horizons within and beyond more horizons, a synchronicity of time that is centered only in the female body. Where does the poem (and / or a residue of language) itself exist in time?

Poems, many of them, exist outside of time, or so deeply embedded in a profound sense of time that they transcend it. Although some will claim that language (like music) unfolds in time, it also (like music) can double and triple time, folding it in on itself or abandoning it momentarily. When it’s good, a poem exists in the extratemporal as well as the temporal, even sometimes zigzagging between the two—which is what the line break does—holds us for a moment in suspension outside time or communication. We get that sensation of all times and worlds being contemporaneous— synchronicity—or mystery—welling in the ruptures of language a poem creates—but also of asynchronicity, another kind of deep time.

A compelling and recurrent energy of Body Clock is the stark interrogation of the qualities of—as well as riotous, lyrical reaching for—the radical possibilities of beauty as a form (or variety of forms). One of my favorite stanzas: “No more fooling around / Make a thing of such / extreme beauty it cracks / and cracks / the hand that makes it” (p. 59). There are many materials that can be utilized in the exploration of beauty. Why are you drawn to words? What are the particular, unique ways that language can access beauty?

In those lines, I was addressing a few things, one of which is our current fear and suspicion of beauty, as if beauty were a cliché, and the possibility that at its most potent it destroys. (I guess that’s an old idea! Think of Helen.) I suspect we’re afraid of beauty for more primal reasons than being worn out on the ideal. And we should not confuse beauty and the ideal anyway. (Must talk to Plato about that.)

Inspiration, too, can be fearsome. I have a few lines elsewhere in the book about that.

I have always found words to be beautiful and mysterious and confusing and frightening. Syntax to be so.

For me, it is the small cracks, the ruptures in syntax or language that flood with illumination. But of course, the music of language can be freighted with beauty and surprise, too.

On the other hand, this is also a work that presences loss, war, bombs, grief, shrapnel. Walmart, Waterworld, and other items of mainstream and pop-cultural kitsch also make into these pages, which cover a number of planes—the pre-temporal, the living temporal, after-death, underworld, dreams, deep sleep, internet, the planetary, the minuscule, the mythological, etc. So there is the seduction of beauty counterpoised to the un-beautiful and suffering. Both extremes are rendered with intense sensuality. What are the ethical concerns of presencing such extremes of experience in art?

In this particular book, which began to gather as such around the pregnant body and the intensely private experience of that, I found it necessary to also indicate the daily world going on around outside the body, but which penetrates the skull. This seemed especially necessary in the period I was working on those poems, because we were at war in two nations, and living under a president who was enacting, in some forms, a reign of terror. The opening section of the book contains a poem I wrote while living in New York, in response to the bombing of the Twin Towers. We were breathing the ash of burnt buildings and burnt bodies. Then we were bombing distant countries. None of it made sense. I wrote the poem to try to make sense, and wasn’t sure I’d ever publish it. As the rest of the book took shape, it made its way there, holding a kind of extremity in place.

That poem focuses, to quite a degree, on the minuscule, on detail: eyelashes, the ball of a thumb, school buses lined up in holding yards in Brooklyn, because in the face of human disaster detail is what holds us to sanity. It probably leads us to neurosis, too, but for me, in this case, it helped me find focus and sense.

The phenomena of beauty, of reality, of possible existences, of absences, of infinite unknowns, of quantum fields, of nightmares, of pleasure spheres further seems to frequently find a palpable position in your words in bizarre expressions of synesthesia. One effect that challenging art and literature has on me is that I am re-awoken to a world that I have become numb to through constant exposure to new and representational technologies. In your process, how do you stay keen to basic and more complex operations of perception?

That is a constant struggle. World dust settles on the perceiving soul. A sense of altertness and humor helps, but we all numb out (I know a few people who don’t much—it can be very hard to live that way). I think you have to train your mind toward alertness, and then you have to train and retrain. Ginsberg liked to say, “Notice what you notice,” but for me it’s not only a cognitive waking-up. Sometimes other forces beyond our control move through to wake us up in minor or major ways.

For a long time, rituals of writing practice helped me. Certainly reading exciting poems or philosophy or fiction, engaging with visual work or music, help wake us up.

Your poems spill across the pages, some of them shapeless or perhaps more accurately compared to the nebular, shifting shape of jellyfish. My instinct is to take this use of the page as cues in regards to how to musically hear these poems (though my tendency to read in this way may not align with your intentions). As books trundle onto digital platforms, how do you anticipate free-form poetry will respond? Is projective verse (poetry written by the breath) possible on digital media?

I do hear the page musically, of course—so we can say we hear space. Line breaks allow that too. Synesthesia is suggested again, in a visual hearing.

Some poets have already been working in digital forms for a while now. Brian Kim Stephens has created some smart and instinctive electronic poetry, but a lot of it has a long way to go. There are also e-reader programs that are working on versions that can handle the page complexities of poetry (I know Coffee House used some of The California Poem as a prototype for that).

We have to think of the totality of what Olson meant by “projective,” and then also take it further. There is the breath and body of the poet involved, but there is also the whole energy field of language and the field of the page, and the interaction between the two, and the energetic relationship not just between the poem and the body of the poet, but between the poem and the world from which it was got (the body is one figure in that world)—it’s a transference of energy, as Olson says, from world to words. We can think of the page as a kind of installation site, moving blocks and forms of energy around. That can happen on the page or in digital forms, yes. I’ve imagined a few possibilities, but would need to work with someone who knows how to create the platforms. I’ve also seen a few interesting French e-books, that are really rich visually.

The collection opens with two epigraphs attributed to Scottish biologist, D’arcy Wentworth Thompson. In Thompson’s book, On Growth and Form, he discusses allometry, or how bodies are shaped in response to anatomy, physiology, and behavior, and gives such examples as the comparable shape of jellyfish and raindrops. I notice that these poems seem to take an allometric position in the process of discovering the shapes and physical properties of time (a drawing of an hour that looks like a flower, for example). How intentional was this poetic allometry in the making of these works?

I wasn’t thinking specifically of Thompson’s allometry, but I was certainly reading Thompson, and I find that theory (and many of his ideas) really pleasing aesthetically, instinctively and intellectually. I experience the world this way. I think it’s why I first loved studying organisms, and why biology seems a natural mate for poetry.

Another recurrent technique of the poems in Body Clock (as well as, The California Poem, as I recall) is the use of footnotes, which tend to interrupt my reading (whether in poem collections or science textbooks) and I grapple with what knowledge I should retrieve first: the whole paragraph or the footnote. In the “Notes on Minutes and Hours” at the end of the collection, you elaborate that the ‘poem drawings’ were the actual experiment of searching for time, and the typed language below is a residue of language. How do language residues differ from footnotes? How does a poem differ from residual language?

Hopefully the reader reads a text more than once, and different things happen each time, but it can be annoying to be deferred mid poem like that.

We could probably argue that all language is residue or remnants, but specifically in Body Clock the language addenda are to illustrate the poem—to allow the reader to be able to read the language that was written into the poem-drawing. The typed version is not the poem itself, but another representation of it. In The California Poem the footnotes sometimes offer information about source, sometimes add more information, and sometimes add more poem (they hypertext the poem, we could say). It’s like you stick your finger on a little part of the poem and another little poem opens up.

You were taught and mentored by a handful of the 20th- and early 21st-century’s most prolific female poets, notably your aunt, Anne Waldman, and New York School poets, Alice Notley and Barbara Guest. In February 2011, VIDA released statistics demonstrating that in the U.S., women are still significantly under-published and under-reviewed compared to male authors (to say nothing of the publication and prominence of transgender, third gender, and genderqueer authors). What advice would you give to the young, passionate, non-male poet?

“Work your ass off to change the language,” said Bernadette Mayer some years ago. We still need to do that. And that means not just in the writing, but in the structures, which is easy to say, hard to do. Will we see a woman president in my life time? I wonder. We have fallen asleep at the (secondary) wheel, lured by the lull of capital and product, which promotes surface and surface thinking. It all looks okay, because we’re trying to look okay. Some have tried looking really ugly (in art-making) to see if that could shake up a brain or two. I’m not sure of the approach, but it’s going to take persistence and hard work, and that work has to be done on the interior and exterior structures. The women you mention worked their asses off and paved the way for me and the next generations. In the avant-garde and small press community (where these particular women and others were working), I think there’s more parity, but when you look at more socially and economically powerful literary communities (which have and distribute more money, and can work to attract more readers), they are still dominated by men. It’s a worldwide capital problem—women are still making something like 70 cents to the dollar, the UN reports will tell you. How long can that go on without a soft revolution coming up?

What forthcoming works do we have to look forward to?

The Loving Details of the Living and the Dead is coming out in the spring of 2013. I’ve almost finished another hybrid memoir/fiction, so that should be coming to the table soon.

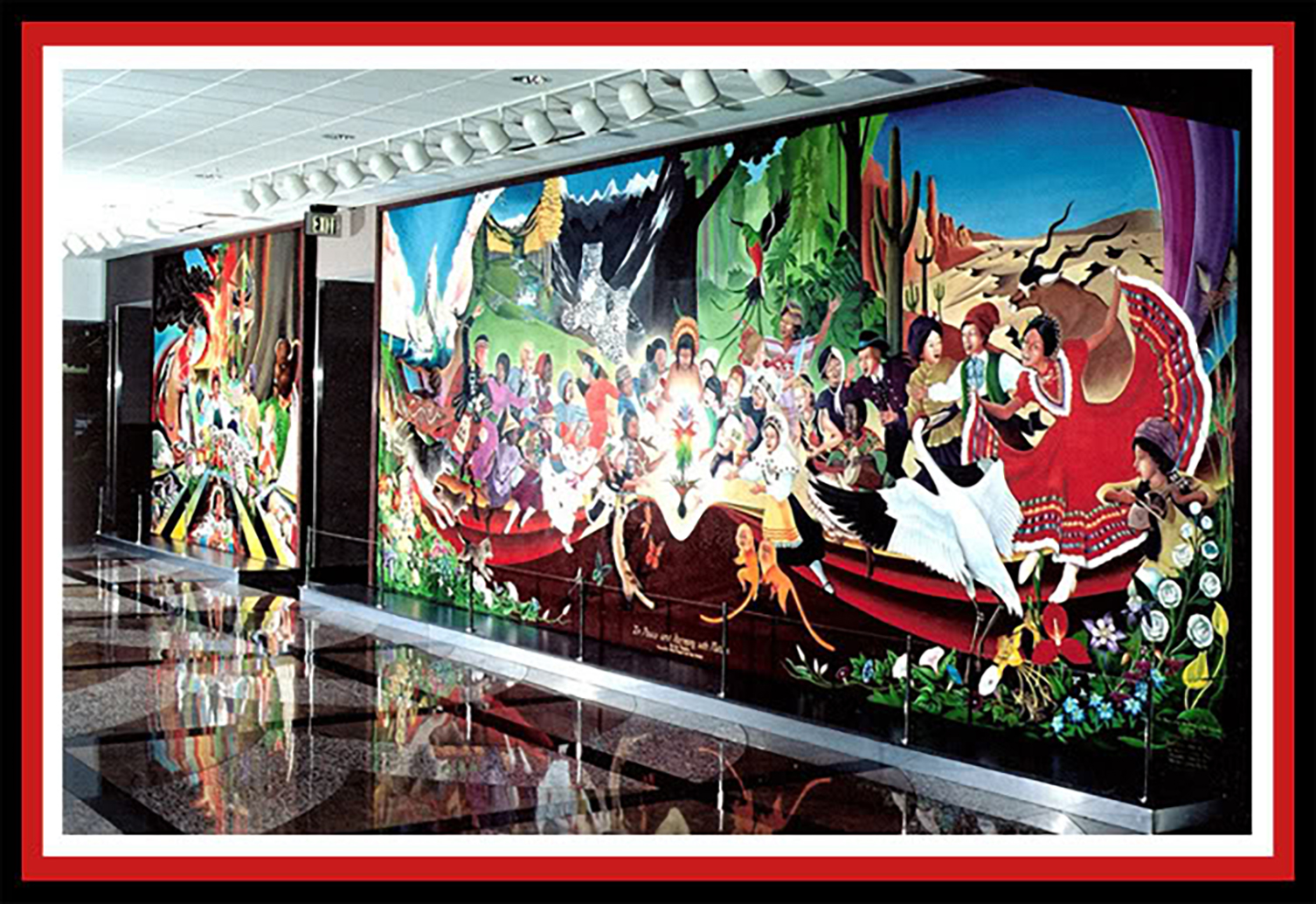

Leo Tanguma, the Chicano muralist perhaps best known by Colorado travelers and the subcultural blogosphere of paranoid doomsday theorists for his dramatic murals at Denver International Airport, creates his complicated pieces through an organic, multi-step process that weaves Mexican heritage, world history, spirituality, progressive social ideals, and personal anecdotes. He made his first mural on a chalkboard in fifth grade, depicting children lynching the town’s corrupt sheriff, for which he was severely punished, and this experience stoked a rebellious verve in his artistic practice that would be played out during the coming decades. Much like Los Tres Grandes—Diego Rivera, José Clemente Orozco, and David Alfaro Siqueiros—from whom Tanguma draws his artistic heritage, he has a keen interest in politics and cultural theory, of which his views swing decidedly left. His sprawling, complicated, large-scale public artworks do contain a number of secrets: portraits of real people lost to street violence, unsung heroes from the margins of history books, and the reexamined Chicano myth of a weeping woman, for example. “Children of the World Dream of Peace” and “In Peace and Harmony with Nature,” the murals that Tanguma created for Level 5 of the Jeppesen Terminal at DIA, were almost never to be: Tanguma barely made the proposal submission deadline. As of this year, he has completed dozens of murals at various public venues across six states, painting themes of childhood courage and idealism, environmentalism, multiculturalism, and Tanguma’s uncanny signature of socially-conscientious spirituality. His most recent work in progress is inspired by the Occupy movement, the pencil drafting of which, sits on a modest, clean desk in his home studio.

Interview by Rachel Cole Dalamangas

Can you walk me through some of the imagery of your murals? Who are the people in the background?

Many of them are real people. This is an anonymous community and an anonymous community can be anybody. In this here, there are the symbols of oppression that our [Chicano] community has overcome. Are you familiar with that figure?

points to a stylized figure with three faces on drafting work for his mural, “The Torch of Quetzalcoatl,” commissioned by the Denver Art Museum

No.

Well it means the fusion of the Spanish and the English when the Spanish came and brought women and began to rape and marry the indigenous women and introduced a new breed called, mestizo. And so that’s the essence of our identity.

And this figure, this is La Llorona, the weeping woman who destroyed her own children after having married a Spaniard, a conquistador. The Spaniard at one point decides to go back to Spain and to take the children with him. Well, that drives the woman mad because to them Spain was like Mars to us or someplace really distant and remote. The legend says that she drowned her children so that the husband wouldn’t take them to Spain, away from the New World. In my mural, I make La Llorona find her children because we get these stories from the Spanish historians and they had a very prejudicial view of the native peoples, that they were less than human, and we get a lot of our folklore from the Spanish males. In my mural she is shown reuniting with her children and it is a very happy occasion.

At the Denver Art Museum, a lot of kids come from the schools, the projects, from schools that have a lot of Mexican-American kids. When I tell the kids about her and say, “Do you know what La Llorona means?” they say, “Yes, we even know where she lives, there under the bridge.” She’s a really intense figure in our memory I guess. But then I tell them, “Don’t you see, somebody said that she killed her own children, but I don’t believe she did it.” Maybe she did, maybe she didn’t, but I don’t want to project that story anymore. So I tell the kids, “I have La Llorona find her children and she’ll stop crying and stop searching for them through eternity, which is what God condemned her to do.” Then I tell the kids, “They lived happily ever after. Don’t you want to live happy ever after.” And some of those kids had tears in their eyes.

Do your murals exist as wholes in your mind or do they develop as you start to draft them?

They develop. I search for ideas. I think it starts with something in my memory. For example, we were Baptists all my years growing up, even though the Baptists are really really conservative and there were ways that some of us weren’t in agreement with the general things. We’d hear from the pulpit, “Hispanic boys will not be found with those protesting,” you know, with those in the youth protest movements, and of course, some of us thought, that’s where we should be instead of sitting at the church.

points to pencil drafts for “Children of the World Dream of Peace.”

This is a lesson from the prophet Isaiah and Micah, that some day the nations of the world will stop war and so on and will beat their swords into ploughshares and their spears into pruning forks. That’s taken from how I was brought up. My parents were really religious when I was growing up, but innocent in their beliefs. I was the one who always questioned everything and I got worse as I got older. So you can see this comes from my religious ideas. As you can see, the people of the world are bringing their swords wrapped in their flags to be beaten into ploughshares.

Then here I have children sleeping amid the debris of war and this warmonger is killing the dove of peace, but the kids are dreaming of something better in the future and their little dream goes behind the general and continues behind this group of people, and the kids are dreaming that [peace] will happen someday. See how the little dream becomes something really beautiful, that someday the nations of the world will abandon war and come together.

What happened up on top here, when we were painting the mural at our studio at a shopping mall, some people who had their kids killed by gang violence came and said, “What are you going to paint up there?” I said, “Well, I have to look at the drawings.” They said, “Could you put my boy or my girl up there? She was killed.” And then they told us her name, Jennifer. This girl, Jennifer, was killed by a young man. She went to help her friend who was hiding with her baby from a man in a motel someplace, and they didn’t have anything to eat or diapers. So Jennifer took her some money and the boyfriend followed her. When Jennifer got to the motel room, the man followed her in and shot her right there dead and then dragged her friend and the child out. So her parents wanted her portrait put up there. They must have told other folks, because before I knew it other people came and said, “I know you, you painted [Jennifer] up there. Could you paint my son, Troy.” So now it’s got like ten kids here, all killed by gang violence in Denver. So the mural took on a new meaning that we hadn’t anticipated. Almost all these kids in here are real people. I put in my granddaughters and their little friends from elementary school. Like more than twenty-five kids from around the schools are in that mural.

The conspiracy theorists have interpreted it in the most naive way, I could say, like they think I advocate war and all these horrible stories.

Have the conspiracy theorists ever harassed you?

Just a couple of phone calls. They were not mean though. They’d say, “Are you the one who painted that?” And some came to my studio and wanted an explanation, which I gave it to them.

Even an explanation didn’t placate them?

Well, the airport never posted a complete explanation. They just put the title, the artist, the materials.

So how did you learn so much about history?

I just was interested in reading.

What happened I think was that something happened when I was growing up in Beeville, Texas, a little town fifty miles north of Corpus Christi. Like many little towns in Texas we had very racist sheriffs and police that liked to keep Mexicans in our place. In our town it was a sheriff named, Vail Eniss. One time the sheriff went to see about some minor thing between a Mexican husband and his wife about their children. The young man was not there, but the father was there. The sheriff arrived there with a semi-automatic rifle – now why if you’re only concerned about a minor incident? So he gets into an argument with the father and shoots him and as he shoots him, there’s other people that were in the yard that came around and he shoots them also. He killed three people in a few seconds. The man at the front was my mother’s uncle, Mr. Rodriguez. So in our family that was talked about. And in other families also. For example, my brother-in-law was put in jail and the sheriff personally beat him with a hose. I don’t know for how long, but severely. It was really really bad. He was just drunk, that’s why he was in jail. So we had a kind of a hate for the system because those things kept happening and the sheriff kept being exonerated over and over and over until he retired with honors.

So you see, we already had a disposition, some of us, that there was something wrong here. Why were treated like this.

When I was in the fifth grade, one day our teacher didn’t show up, so a lady from the office came and said we were going to have a substitute and later she would arrive and for us to stay at our seats and behave. And when the lady left everyone began to play and talk and stuff. Some kids went up to the blackboard. I was more reserved than most folks. We were a little odd. Some of us were Baptists in a community that was almost totally Catholic. So we were a little more reserved. I was sitting down for a long time and some kids were drawing already and after a little while I said, “Okay I’ll go draw too.” So I went up to the blackboard. I didn’t know what I was going to draw, but before I could draw, somebody said, “Pollo, draw me killing the sheriff.” Also all the kids began to say, “Draw me too! Draw me too!” So I started to draw the sheriff hanging or being stabbed. Then the substitute walked in. She was outraged at what she saw. Of course, when I saw her, I ran and sat down, but she had seen me already. She looked at the drawings and she said, “You, come here and erase this garbage.” I began to erase it and she got a ruler and began to hit me across the back. She was in a rage. And I began to cry. I guess I couldn’t see too well because I thought I was done erasing so I ran back to my seat and she said, “Come back here, you’re not done yet.” Because I hadn’t finished it completely. So I erased it completely. She hit me a few more times on the back. I don’t remember too much about what happened after that. Whether I went to sit back down or just stood there. For a while I stood there.

Many people have asked me when was your first mural, thinking I’m gonna say something like when I was in the boy scouts or something like that.

That I think started something in me.

Tell me about some of your artistic influences.

I met the professor in the art department, Dr. John Biggers, at the Southern University in Houston, Texas. He was a radical and he admired the Mexican muralists and he taught about them in a class I was in with him. Then I told him about the murals I was painting. And we became friends. So I was so influenced by Dr. Biggers. And he said go see the muralists in Mexico City.

What happened in my case was there were people, Los Mascarones, – masks – and they did a performance and so after the performance a lot of those kids [in Los Mascarones] stayed in my home. I had an enormous living room. After the performance they were at my house and the kids were sleeping already and I was having coffee with the director of the group and I asked the man, “Do you know anybody who could get me introduced to Siqueiros.” I was asking this guy – Mario was his name – and he said, “That’s his grandson sleeping right there.” I wanted to go wake that kid up. In the morning, I said, “Could you introduce me to your grandpa?” And he said, “Sure, just come on over.” So that’s how I met Siqueiros.

It was real funny. Siqueiros talked about some of the other guys, like, “Those guys can’t paint,” talking about Rivera. It was funny because Rivera is a Great. A great, great master. And then Siqueiros said, “Tamayo was okay, but one time we had a fight at the Palacio de Bellas Artes in Mexico City.” Siqueiros said that one time he and Tamayo got in a fight at the top of the stairs and rolled down the stairs.

Do you know much about the great muralists from Mexico?

A little bit . . .

Well Siqueiros was the most outspoken of them. Before the revolution began, like 1911, he was a student at the Academy of San Carlos in Mexico City. He and the other guys, he must have been 14, 15, and they were meeting already about political issues that were being discussed in Mexico before the revolution. And Siqueiros talked about this when I interviewed him. It was another awakening for me. Siqueros was so dynamic and a little reckless also. Do you remember Trotsky? Trotsky separated himself from Stalin and the rest, and Trotsky was a little more progressive I think. But Stalinists thought that he was dividing the worldwide communist movement and so they wanted him killed. Siquerios was a Stalinist in those days when he was young. When he was older he didn’t want to talk about it. He’d say, “We were young then.” He tried to assassinate Trotsky himself before Trotsky was finally assassinated. And that’s the way he was, kind of crazy and reckless and so on.

But to meet him when he was, I think, 72, it was quite an experience for a young person like myself. So I came back thinking, “Wow, I met a master, a real master.” Because there were many of us painting murals, but we didn’t know what we were saying or what we believed in or what our purpose was in painting the murals. I came back with a little more beliefs.

How many murals have you painted in Colorado?

I don’t know. But I’ve got some in schools, the high schools.

And some in prisons, too, right?

Did I do one in a prison? Yes, that’s right. In Greeley, there’s a youth facility. We did two murals there. When we were working in the prison the kids there were 10 years to 20 years of age. They didn’t call them inmates, they called them students. They were there for different offenses. 37 kids volunteered to paint murals with [my assistants and I]. We told them the way we were going to do the murals was each of them was going to sit down and draw from their own experience how they got in trouble, how they got their lives messed up at this early stage, and they were going to draw that and then they were going to draw another drawing about how they were going to improve their lives. So many kids didn’t like the idea so they quit coming in. We only had 15 kids. But some of them couldn’t see a way out. This one girl, her name was Alicia, she drew some big bottles like alcohol drinks and there was a little girl at the bottom lost in alcohol. And I said, “Okay, now what’s the other one, how are you going to get yourself out of this?” And she wouldn’t do it.

Everybody painted a portion of the mural, about two and a half feet wide by twenty inches high, and they would paint how they had gotten in trouble, the life they had, and how they were freeing themselves from that. And Alicia left hers just like that. She said, “Once an alcoholic, always an alcoholic.” So I could never make her go beyond that. Another kid named John, he drew himself in a big rat trap, and I said, “Well, what are you going to do when you’re on the other side?” And he said, “Once you get in drugs and messed up, that’s the way you’ll be forever.” And I said, “No.” And we were kind of preachy the three of us, my two assistants and I, we were trying to tell the kids there’s something better out there, like, “Paint yourself some other way.” And John did change his drawing. He’s got the kid trapped and then in the other one there’s a trap with the wire back and the kid’s standing next to it, because he’s gotten himself out of that situation. And that’s how it’s painted on the mural today. It was therapeutic, what I was doing with the kids.

I’ve told my students, “We have to have a higher purpose with our art here, not just to sell it so people can take it and just decorate their homes, but do something more positive.”

Can you expand on that? What is art’s role in cultural and political conversations?

Well, the Mexican muralists after the Mexican revolution proceeded to paint the people because many of them had been with the revolution and had seen the struggle of the people and they saw firsthand how art could return to the people a sense of their own dignity.

Just to give you an example of how the elites in Mexico saw their own people, Mexico celebrated its 100th anniversary in 1910 and to celebrate the 100th year they invited an enormous exhibit of art from Europe, from Spain especially. Now how did those guys see the Mexican people, the Mexican artists especially. Why couldn’t they have an exhibit of Mexican artists celebrating Mexican independence. So that could give you an idea of how the rulers saw their own people.

My activism was in painting murals and working with kids and so on, but in my case, I already had the experience of being back in Beeville with the sheriff, and drawing him on the blackboard. The young people see themselves in the murals.

And in my background I had never gotten away from my beliefs. Because my parents were so beautiful. Memories that you could never forget. Like before going to bed, my little brother and myself and my older sister, and everybody’s going to bed, my mother takes a little time to sit in her rocking chair to sing or just hum hymns, and I grew up seeing that. Or hearing my mother or my father at the dinner table saying, “Remember the poor.” A list of things that they repeated almost in every prayer. So that was the kind of innocent background that I had in my case.

Some other artists did it because the Mexican painters were revolutionary in the Marxist way. Being not very easy with words, I tried to read Marx, but it was just too complex and boring. On the other hand, the Bible was easy for me and to see it in my family and going to visit my brother in prison and seeing all those things, they were impacting me.

So as I began to read history, Mexican history and then the history of us here in the U.S., and I saw how I could contribute.

For example I painted a mural about black and white. It was four or five feet off the ground, 18 feet higher up, and I painted many bodies, brown bodies, because we had been made to feel inferior to the whites. I remember seeing also in the 7th grade for the first time the black kids, the Mexican kids, and the white kids were all together, and I remember the black kids, when they went to speak to the teacher, and the teacher spoke to them, they lowered their heads. We were pretty bad, us, the Mexican kids. But we didn’t do that I don’t believe. We didn’t look the teachers in the eyes very much, but we didn’t lower our heads I don’t think. And I thought that was out of some humiliation and as I studied more about blacks and other oppressed peoples, I could see that what I had was an instrument in my hands that I could use to return to the people a sense of their history and their beauty and their human dignity. And people responded to that. They like those kinds of explanations.

Tell me about what you’re working on now.

I’m thinking about this mural for the Occupy movement. I don’t have funding yet. I think it’s very important and very interesting, what the young people are trying to do with that.

Anicka Yi, Sister, 2011. Tempura-fried flowers, cotton turtleneck, dimension variable.

We were introduced to Anicka Yi’s work at 47 Canal, an LES Gallery operated by Margaret Lee and Oliver Newton, who played host to Anicka’s first solo show, Sous-Vide, last September. We met the artist for a studio visit in the space earlier this year. Anicka’s materials are unexpected and her process is unpredictable. Works like “Sister” demand a complete sentient analysis from the viewer, placing them in unfamiliar territory beyond the purely visual and inspire a multiplicity of ideas and emotions.

Interview by Kriti Upadhyay

In your artist statement, you say you are drawn to perishable materials because of their affect, their aesthetic qualities, and their resistance to archive, permanence, and monumentality. How have you counteracted the challenge this presents to the creation and exhibition of your work?

I don’t know that I’ve counteracted the challenge of making and exhibiting perishable materials. The syntax of the work continues to develop and hopefully becomes more fulfilled. I’m developing sensory assets in order to explore the way language, media, and economy mediate technologies of the self and ways in which art making can be pushed towards an expanded notion of the sensorial. I’m interested in connections between materials and materialism, states of perishability and their relationship to meaning and value, consumerist digestion and cultural metabolism.

What first drew you to combining these materials with aggressive techniques such as deep-frying and sous-vide? Do you have any culinary training?

I don’t have any culinary training but possess an affinity for radical technique. Deep-frying is such a base form of achieving flavor incorporating so many fascinating formal attributes—texture, sense of touch, smell, sound, sensations of temperature and pain, fragility. I love the violence of the process. It’s high drama. So is the process of vacuum sealing food to slowly parboil it for 72 hours. These are all techniques of desire that [circumscribe] Taste. Taste is about thresholds. We’re all implicated in the politics of taste which are problematic. I’m interested in liminal, dangling spaces between a fully realized “biological” experience of taste and what is often at odds with this as conceptualizing taste. How the transglobal contemporary consumer apparatus appraises taste. I think some of the most radical art that has been developing in the last 10 years has been in the culinary arena, El Bulli, Noma, Subway sandwich franchises by example, but especially the dominance of the flavor industry on our reality. I’m drawn to the totalizing experience of the art of “taste”: the performative, the formal, the theatrical, the sensorial, the metabolic, the irreducible unique moment. This arena calls into play the concept of taste and value through biological/chemical sciences, economics, emotional and sensory triggers (receptors).

The deep fried flowers bouquet installations are an aggressive treatment of tactility—surface textures, simultaneously inviting and repelling touch. Each flower stem was individually coated with tempera batter and panko crumbs then deep fried in a deep fryer. I wanted to impose violent techniques on delicate, fragile materials to expose vulnerability, stages of metamorphosis, delineate different strains of matter and perishability. To exaggerate the weight of the batter and crust onto the light, ethereal quality of a flower. Flowers are enjoyed for their “natural” beauty and purity. They needed to be “messed” with to bring out other qualities, to address questions of purity, beauty, perishability, decay.

One of your works, Convex Double Dialer of a Shining Path, heats together “recalled powdered milk, abolished math, antidepressants, palm tree essence, shaved sea lice, ground Teva rubber dust, Korean thermal clay, and a steeped Swatch watch” on an electric burner. What leads you to such specific combinations of materials?

I’m drawn to speed and vectors from different economies and timelines. The elements in Convox Double Dialer collide, co-mingle well together as language as syntax. I like the sensorial/cognitive scramble. It’s earthy and cosmic. My work is language building. It’s word building, by what certain elements, say, the recalled milk, abolished math, antidepressants, palm tree essence, etc. mean. Whereby Signifier, exchange and use value are all entangled. They’re like poems. For instance, in one of my sculptures there is MSG (a flavor enhancer) a big metal bowl. [You Should Hire Me Because My Kiss Is On Your List] I get asked Why MSG? MSG could always just be the right grain of powder but it could also be something else. It’s neither nor. It depends on the syntax. There’s no right answer for why MSG? It’s equivalent to asking why De Kooning used red in Woman Painting. It could be that MSG was used because it happened to be in a shop downstairs from the studio where the sculpture was composed. It could also be that MSG is very commonly used in Asian foods. The materiality is about the triangulations between the thing itself as aesthetic qualities—the language and the social/visual implications of the things. I applied Shining Path to the title because I was thinking of timescapes, like when Wipe out the past and let the future take care of itself.

How much experimentation usually occurs before you think you’ve achieved a work in its final state?

A lot. They rarely ever feel final.

Following up that question, what have previous failed experiences taught you to avoid?

Avoid a trip to the Emergency Room.

What have been your favorite ingredients (if I may call them that) and processes? What’s something you would like an opportunity to experiment with?

I’d like to explore more bio-technologies. Cryogenics, grafting, impregnating materials.

You force the observer to confront barriers such as scent and edible medium. Should they consider this taboo? If not, how should someone approach viewing your work?

Nothing is really taboo. One could approach my work with a presentness of biological and intellectual receptors. Be prepared to crank up the memory machine.

You explained to us previously that you’ve attempted to visually represent the metaphor of art as a metabolism in previous shows. Do you plan to translate this idea into any other mediums?

Mostly through writing and performance.

Your exhibitions and works have memorable titles such as “Excuse Me, Your Necklace is Leaking” and “Yes, It’s Made for That.” What goes into these names?

Poetry, humor.

Finally, we discovered you’re really into post-apocalyptic sci-fi novels during our studio visit at 47 Canal. Can you see your curiosity in a concept like the “Apocalyptic Sublime” ever intersecting with your process as an artist?

The work feels, looks pretty sci-fi already, doesn’t it?

Detail from Becoming the Spectacle: The Virgen de Guadalupe, Aztec Goddess, the Mariachi, and the Donkey Lady, 2011. Photo: Chad Gomez, SA.

The San Antonio based Más Rudas Collective [MRC] is Ruth Leonela Buentello, Sarah Castillo, Kristin Gamez, and Mari Hernandez. “Más rudas” resists English translation. Instead, a demonstration: the four artists were recently kicked out of the Alamo by security—the strong arm of the Daughters of the Republic (of Texas)—for showing up there in costumes including a mariachi, an Aztec princess, the Virgen de Guadalupe, and the Donkey Lady of San Antonio (a local urban legend). Another act implied in their name is the simultaneous ancestor-honoring maintenance and radical revision of what it is to be Chicana/o. They refuse to relinquish identity to the altar of contemporary art. This tenacity has been rewarded in their short, rocketing career with a residency at Slanguage in Wilmington, L.A., installations and solo shows at the Mexican American Cultural Center in Austin and the Guadalupe Cultural Arts Center in San Antonio, the cover of Chicana/Latina Studies: The Journal of Mujeres Activas en Letras y Cambio Social, and in Fall 2012, the Window at Artpace San Antonio, to name a few.

C/S

Interview by Josh T Franco

I have been following Mas Rudas Collective since the “Quinceanera” show a couple of years ago now. I have questions I’m eager to ask about that show and the really rad projects that have happened since, but first, can you tell me how you all decided to come together as a collective in the first place? Do any of you still maintain studio practices on your own, or is this an all-in kind of deal?

Our efforts towards establishing an all female collective was sparked by Mari Hernandez. We started collaborating in efforts of having an all female DIY art show, “Our Debut,” in December 2009 in a friend’s living room. We all welcomed the opportunity since we felt the SA arts community overlooked Mexican-American artististas and because we didn’t connect to the majority of art being shown in San Antonio. Through our collaborative efforts in discussing, creating and organizing “Our Debut,” we decided to continue collaborating as a Chicana collective, which we solidified under the name, Más Rudas.

Individual studio practices are still kept while the collective works together on our collective exhibitions. Each form of practice, individually and collectively, ignites a flame in the other.

It is saying much to say that Mexican American artists are overlooked in San Antonio. I’m definitely intrigued. Can you specify what you all mean when you say “the SA arts community”? I am pushing this because many San Antonio institutions claim to do precisely just that: represent Mexican American artists. I’m thinking here at some radically different registers as well. The Smithsonian associated Alameda Art Museum and the grassroots San Anto Cultural Arts, to name just two out of perhaps a dozen, are obviously very different, but they do share that claim. But you are saying something was still missing. And I wonder if the crux is generational: our generation has such a tense insider-outsider relationship to the notions of El Movimiento and La Causa for instance (moments some institutions attempt to capture as their acts of “representation”, e.g., the Alameda’s Protestarte show of decades old protest posters). We weren’t there in the 60s and 70s, but the living legacies of those times are always very present in our daily lives, especially when living in a city like San Antonio. Or perhaps it’s a mix of that and gender. I’m thinking of the fact that some key pieces in “Our Debut” were premised on the recognition of an absence; that though the artists, some of you, are Chicanas, you had never had a traditional quinceanera. Each generation seems to undergo major shifts in how or whether Mexican traditions live in our US/Aztlan lives. We can think back to Pachucos and Pachucas for instance. What was not being represented before Mas Rudas began working in San Anto? And how is that absence addressed in your projects? It may or may not have anything to do with the issues I have raised here.

For us, to be Chican@ is to be Mexican American. From our experience, to be a Mexican American artist and refer to ourselves as Chicana is something, we’ve realized, is not readily acceptable in the art world. Identifying as Chicana has lead to some criticism. We’ve been told that we are pigeon holing ourselves as artists and limiting our opportunities. We’ve also been told in order to be successful we would have to make art that represents things outside of our culture and community. If our voice as Chicanas was represented than the fear of the label wouldn’t be as common. Because of this fear we feel as if we are overlooked.

While San Antonio has a large, diverse, and vibrant art scene it is rare that we are able to go out and see art that reflects our experiences. There are a handful of cultural art institutions that cater to Chican@ artists and we are thankful for that. The major art institutions in the city are predictable in the artists they show and represent. Rarely will you see a woman of color as a feature.

We realize that we owe much to the Chican@ artists and leaders that came before us. These individuals have paved our way and are a source of inspiration. Time and place set our views apart. We have different ideas and we were born into a different world, therefore the art we produce is different.

We know many artistas, many Chicanas who deserve as much, if not more, recognition than we have gotten. We are adding to the underrepresented Chicana voice in our community, not creating it.

How does the name Mas Rudas reflect this position?

Mas Rudas is a name that we created, embraced, and defined (because we can). With our name we take an unapologetic stance. It is the pride we take in who we are, where we come from, and the work we produce.

As an adoptive parent to a West Side San Anto dog,—shoutout to Gobo—I really appreciated operation canis familiaris. What was especially striking was the range of representations of dogs; the hagiographic portraits and altares, the crime-scene-esque floor piece, and the immersive, narrative environments, just to give some idea. It also made me look again at works like Francis Alys’ El Gringo and Helena Maria Viramontes’ novel Their Dogs Came With Them. There are some interesting conversations to be had there. What was it about dogs that enticed you all as artists? Did you get to know any dogs particularly well doing the project?

The city of San Antonio has a major problem with stray animals. While in recent years the city has created programs that raise awareness regarding the issue, it’s a problem that won’t go away unless the community becomes involved and takes action and responsibility. Sometimes we see dogs that are more like accessories, representing a level of machismo or affluence. Some are chained in a yard all day, acting like an alarm system, warding off possible intruders. Others are running around in our neighborhoods, neglected, hungry, dieing in the streets, and reproducing at alarming rates. We want to bring awareness and promote dialogue about the issue. Sometimes you have to be creative in your presentation in order to grab attention. There is a growing community of stray animal supporters in San Antonio.

These are people who have taken initiative and dedicate their lives to saving neglected, hungry, abused, and uncared for animals in our streets. They selflessly give their money, time, and energy to fixing a huge problem in our city.

Most of the dogs presented in the installation were strays. Mari Hernandez’s dog portraits concentrated on family pets that were rescued.

What was it like working on “Homegirls” in LA? Did any ongoing relationships or collaborations come out of that show?

“Homegirls” was based on work featured and inspired by another member of our collective. This gave us the opportunity to explore our relationships. Developing our relationships is essential in our collective process. It adds depth and cohesion to our work. Spending a week with each other and driving to and from LA was a great bonding experience. We even got a Más Rudas tattoo to mark that important moment in our lives. We are a family.

Homegirls has been our first and only out of state exhibition so far. During our time in L.A. we were able to meet and speak with likeminded artists. We feel as if the Slanguage community truly embraced us. It was a very welcoming environment. In retrospect we see many similarities between San Antonio and Wilmington. The warm people, the culturally thick environment, and the sense of pride and responsibility the people shine with reminds us of our own city. Karla and Mario (Slanguage) were excellent hosts and really provided us with an opportunity that has helped us grow as a collective as well as individuals.

Does the concept of rasquachismo figure into your conversations as you create together? I am wondering how, if, this idea has currency for young Chicana/o artists today.

It definitely does. We concentrate on producing in practical ways because we have to. We are just like any other individual trying to hold down multiple jobs, juggle work and school and pay the bills. Rasquache means to make the most from the least. It’s embedded in our culture and our way of thinking. It’s also something we are very aware of because we want to show that you don’t have to be rolling in cash in order to be an artist or to be creative. It’s nice and a definite privilege to have the financial means to support your creative dreams but it’s not necessary. There are ways to work around a lack of funds, that’s rasquache.

I am really excited to see what y’all will do at Artpace, where Mas Rudas will be in the Window Works artists starting in September. What was it like to receive that invitation? Can we get some ideas of what we might see?

Artpace is a leader in contemporary art and their invitation to us was a great compliment to us as artists. This opportunity will expose us to new audiences around the world. We hope that our (a small group of Chicanas whose first show was out of the living room of a friend’s house) invitation to Artpace encourages fellow artists in our community to reach far and wide.

In true Mas Rudas fashion our upcoming installation at Artpace will transform and activate the space provided. We promise our theme to be thought provoking y puro Mas Ruda.