Raphael Fonseca, photo by Randolpho Lamonier

“Who tells a tale adds a tail: Latin America and contemporary art” curated by Raphael Fonseca is on view at Denver Art Museum through March 5, 2023.

Interview by Brandon Johnson

The exhibition title is inspired by a Brazilian proverb “Quem conta um conto, aumenta um ponto” translating to “who tells a tale, adds a point,” which emphasizes the conversational nature of the work. There’s a pun happening in English with “tail” that echoes “tale,” a story that is embellished in nature. In what ways do the artists in this show craft their own narratives, and how do they communally craft the narrative of the exhibition? Is there any embellishment to be found among these narratives?

I feel that the artists craft their narratives in many, many ways. As a curator, I feel that this is the coolest part of working in a group exhibition with so many commissioned works: with an invitation, we can see and collaborate with many different narratives, medias, and points of view. In this sense, the show is no longer (or perhaps it never was, actually) “mine,” but has the authorship of this amazing group of creators. Some of them are interested in very personal narratives, oftentimes related to their biographies and even to their families, while other artists prefer to look at the boundaries between the notion of “story” and “History,” choosing specific episodes and creating very interesting tensions. I feel, now that the show is open, that most of it (and most of my other projects) is very based in this tension between the macro and the micro narratives.

Most of the artwork in the exhibition is commissioned, which is not always the case for museum shows. What was your process in working with the artists to develop the work? Did you already have in mind specific spaces for individual artists within the idiosyncratic spaces of DAM’s Hamilton Building?

The fourth floor of the Hamilton Building is very, very challenging; it is not easy to deal with all its sloped walls, angles, corners, and peculiar ambiances. When I started working on this project, it was clear: we cannot deal with that space like it was a white cube . . . and, in my opinion, it is difficult to simply hang different works by different artists on the same wall or even in the same perimeter. So, yes, I thought that it would be more interesting to “split” the space between the artists—including, of course, the hall close to the elevators and the new amphitheater at the Martin Building. This way each artist could feel freer in their proposals of occupation of these specific segments of the space. After months of discussions, little by little it became clear which artist should occupy which space. It was pretty organic.

I noticed that while the artists are originally from a variety of Latin American countries, that many of them are currently based in the United States or Europe. Do you believe this geographical and cultural distance gives further perspective to the artists in developing the narratives of their work than if they continued to work in their countries of origin?

Absolutely. I feel also that this is a common characteristic of this generation of artists—a generation I am also part of. Many of the artists, like Claudia Martínez Garay and Tessa Mars, studied abroad— they studied in Amsterdam, at the Rijksakademie—and there they stayed. We discussed a lot about this topic: how does the fact that you are not living in Latin America anymore influence your work? How do certain international communities look at your work? Does it make sense to still make works that quote and discuss explicitly “Latin American culture” if these artists have not been living there for years? The discussion is long and multilayered, but I feel that some of these artists avoid any approach to their work that could put them into a box, locking further interpretations of their research.

The 19 artists in the exhibition are all of the millennial generation. What significance does this age group hold for you in relation to the production of art? Is it an emphasis on technology and identity?

To work with this generation means to work with artists that were born before the internet was everywhere; even with the artists ranging in age from 26 to 41 years old in the exhibition, we all remember the day that someone told us about internet, social networks, mobile phones, and more. This common point certainly brings to the artist a certain approach of appropriating previously existent images, storytelling, and all the boundaries between that which can be considered “truth” and “lie.” All these aspects seem very clear in the show to me. More than that, I also think it is a great opportunity to gather artists that, in most of the cases, never had the opportunity to show their work in a museum in the United States. To some of them this is not only their first ever exhibition in the country, but also the first time they even travelled here.

When you first conceived of this exhibition, did you have it in mind to feature artists who had never shown in United States museums previously? If so, what did you hope to achieve in introducing these artists to an audience in Denver, and the United States more generally?

Yes, I had that in mind—it is something that I always try to do in all my projects. It doesn’t make sense to me, as a curator, to only work with artists that are very well known and full of recognition in a global perspective; I think it is part of my responsibilities as a curator to take the opportunity to always have a balance of artists in different institutional stages in their careers. Naturally, then, these reflections came to my mind during the investigation process that resulted in the show. I hope that the exhibition can contribute to a broader reflection on what the idea of “Latin American art” could mean nowadays—not only in Denver and in the United States, but also in a broader, international perspective. If people visit the show and felt that somehow the idea of “Latin America” can be read as a fiction full of contradictions and multilayered interpretation, I think I have reached some of my goals. If the artists in the show are, in the future, invited to do other projects in the United States—not only, I must say, projects dedicated to the region of Latin America, but also other exhibitions related to contemporary art in a wider perspective—I also will feel that I have reached my goals. Curating is all about sharing, and I really hope that “Who tells a tale adds a tail” can be seen as a starting point to other art professionals (curators, directors, professors, collectors, etc) share these artists’ research in different opportunities.

Borjana Ventzislavova, Meet me in the red room (behind the curtain), 2018, wallpaper print

Borjana Ventzislavova, Meet me in the red room (behind the curtain), 2018, wallpaper print

Water Walk With Us, by Borjana Ventzislavova, curated by Gregory Volk, is on view at Radiator Gallery, 10-61 Jackson Ave, Long Island City, Queens, New York, through July 8, 2022. Friday 3-6pm and Sunday 1-6pm.

Interview by Gregory Volk

Borjana, your exhibition includes references to early 1990s post-communist Bulgaria, the Canadian Rockies and…Twin Peaks. Twin Peaks???

Well, yes, exactly—the reality in my hometown Sofia, where I was living in the early 1990s, was not far away from Twin Peaks’ reality. It was just after the fall of the Iron Curtain when on Bulgarian National TV during prime time, and after the news, Mark Frost and David Lynch’s series Twin Peaks was broadcast. So you sit down with your family in front of the TV and watch these wonderful, really strange scenes, something you never saw before, something that for many was also a kind of first encounter with the West. And we all hoped back then that the West was going to be the best. And then I would go out on the streets with my friends and play a Twin Peaks-inspired game. We would take our shoes off and cross the street to the taxi stand, and say to the driver, “The owls are not what they seem”… and he probably would have known what we were talking about. Because back then we didn‘t yet have private TV stations. We had only Channel 1 and Channel 2, and that was it. So the whole nation was watching Twin Peaks, imagine that. And me personally—a teenager at the time, going through changes, growing up into some kind of adulthood—it seemed to me that the whole society and the world around me felt not much different than a confused teenager, in the throes of puberty, who finally would find what it was looking for throughout its childhood—a bright, democratic future. And then you enter the world of Twin Peaks.

Who killed Laura Palmer? But also, who killed whom on the streets of Sofia? The newly-formed mafia back then were killing each other, including political figures. on almost a daily basis. So even far away, somewhere in America, in the small town of Twin Peaks, mysteries were more easily revealed than was the case with what was going on in my own city and country.

Borjana Ventzislavova, Wonderful and really strange #2, 2018 (from the installation Ten Peaks or Water Walk with Us), mixed media, framed

Strangely enough, I got a flashback of that time while I was doing a residency at the Banff Centre for the Arts and Creativity in the Rocky Mountains a few years ago. Provoked by nature and the atmosphere of the small town of Banff, which made me feel as if I were in Twin Peaks (filmed not far from there, in Washington State), I teleported myself back into the ‘90s to understand better what exactly happened in this essential moment of change and transition. There were questions that always bothered me but for which I never took the opportunity to find answers and connect the dots. What were post-communist societies—Bulgaria in particular—going through, what exactly did the Iron Curtain mean and for whom, what direction were we following, where were we going and why? And did we arrive somewhere? If so, where? At the same time, I had to rethink how all this related to a teenager who was also just discovering the music, books, and films that played a really important role for me not only then, but for my whole life. And all of this merged through the prism of close friendships.

So you see, all this was very complex, and very personal too, but also revealed some crucial aspects of the narrative of collective history.

You are an urban woman, having grown up in Sofia, Bulgaria, and you’ve lived for many years in Vienna, yet nature is crucial in your exhibition, including your video Wahkohtowin. Can you address this? What happened in Banff?

To be honest, I don’t know exactly what happened. My explanation is that the power of nature and the attempt to overcome a state of anxiety was what conquered me. I think there were a few moments which somehow intersected, but the major aspect throughout the whole process of creating this body of work was that I decided from the very beginning to follow only my intuition. My work is usually based on both theoretical and empirical research. Here, my approach was different from the very beginning. I didn’t want to necessarily produce new works while in Banff. But I had this very personal story where someone very important to me was very sick and was going through treatment back in my second hometown of Vienna. I felt very bad that I was not around and had to leave for my residencies (Athens, and then Banff). Upon arriving in Banff, I recalled this work that we had made together a long time ago: “Wishes for Fishes” (2002), in which a woman in a red dress navigates the city in a very clumsy way (frame by frame), accompanied by underwater sounds, and then this feeling of being breathless and in a vacuum is broken by scenes where she is jumping rope and singing. I don’t know why this particular work came back to me, but I was sure I should do something with the jump rope scene and I decided to present it more as a collective ritual, so I invited a few people to perform that and jump rope outside in nature, dressed in red. While I was looking for red clothes in the theater department of the Banff Centre I discovered this very beautiful traditional dress, which I didn’t know what and where exactly it was coming from, as it was also for me the first time I got closer to indigenous history and traditions, but somehow it reminded me a lot of a Bulgarian traditional costume. So I went back to my studio and looked it up, and I found that this dress was of course an indigenous regalia called “jingle dress.” The whole history behind it (and there were a few different versions of the story told by different First Nation and Native American communities) was that jingle dresses, also known as prayer dresses, are believed to heal the sick, and the dance is perceived as a healing dance. In the context of how, why, and for whom I started this project, this aspect made complete sense, and the work became absolutely important to realize. So I invited five colleagues/residents at the Banff Centre at the time—artists, performers and musicians—to take part in the video by jumping rope until they were completely exhausted. All performers were dressed in red. I was able to get in touch with people from the indigenous community outside the national park and to collaborate with Shaunna, an indigenous dress dancer who at the end of the video is dancing the jingle dress dance in her own regalia and performing the dance for the person who was going through this painful treatment and illness at the time.

Borjana Ventzislavova, WAHKOHTOWIN, 2018, HD Video, 13 minutes, color

Borjana Ventzislavova, WAHKOHTOWIN, 2018, HD Video, 13 minutes, color

For many years in my work, water has played an essential role. All locations where this video was shot are next to or above water sources (e.g., the Banff reservoir, which is underground, so sometimes water is not visually present). This was the criterion for selecting the landscapes for the video. Water has many meanings and symbolizes many different aspects of human existence and life on earth in all different cultures and communities, and for me it is an element I ended up using unconsciously at the beginning of my art praxis, until at some point I realised that in every other work I play somehow with the element of water, whether visually, acoustically, or as a philosophical metaphor. The title of my video Wahkohtowin is borrowed from Cree language and Cree law, and it literally means “kinship” or the interconnected nature of relationships and natural systems. This is a concept I then discovered to be part of many other works of mine, but that’s a different subject. So yes, the water somehow here too has this connective role, an element that unites us, that connects us, that is us.

But going back to your question, since I had to deal with wild nature (and—you’re right, I am an urban person), in order to cross the woods every day to get to my studio I had to look around to avoid confrontations with a grizzly bear, an elk or at least a Bambi family. So I had to go through a lot of anxiety, but this also helped me somehow to overcome my fear of danger. After I had a really strange and scary confrontation with an elk, then a few wonderful ones with deer, I started developing a very interesting approach to nature, maybe a very naive one, it’s worked for me since then. We are part of nature, and if we respect its rules it works for its members. So I stick to this rule and try to be respectful of my surroundings, to feel them and to act in the most adequate way possible. And here again, I never realized before that the mythology of art and culture can play such an important role for or against self-identification, recognition, and appreciation.

Objects, including red curtains and silver stones, have pronounced power in your work, but also seem like enigmatic evidence collected at a crime scene.

Silver, red—yes! As I mentioned earlier, there was no plan to follow. And that was on purpose. So I wasn‘t looking for anything.

But, of course, there is so much going on inside you, and then you have some kind of sixth sense and start to follow signs, like Agent Dale Cooper in Twin Peaks, who collects evidence to reveal who killed Laura Palmer. In my case, objects are just appearing without my even knowing their exact stories, but something tells me: here I am.

I used to work a lot with the color silver in the years before this project. Sometimes this would relate to the Iron Curtain and the illusions and fantasies we had of what was hiding behind it, or sometimes I would color objects of the past in silver, and another time my intervention involved wrapping the whole facade of my gallery in Vienna at the time with mirrored silver foil, a work called “Hey you, it‘s us!“ and so on…so I had many works that used silver. And then you walk in the woods of Banff Centre to get to your studio and something is shining in the high green grass…a big silver stone. Is the color natural, did someone paint it over? It doesn’t matter, it’s a silver stone.

Then again in the theatre department, while I was looking for red clothes, I found two rolls of red velvet fabric wrapped in plastic, almost like a dead body lying on the floor. And you remember in your childhood you used to see this red velvet frequently, the color of the Communist Party, the color of your red pioneer scarf, the color of all curtains, whether in movie theaters, cultural centres, or just the Lynchian curtains from the red room. The red room, known also as the “waiting room,” this anomalous extradimensional space, which connected to a grove in Twin Peaks’ Ghostwood National Forest, was believed by many to be the Black Lodge of local Native American legend. Anyhow, many spirits and spectres appeared to “live” in the red room…or behind the red curtains. And so, after the appearance of the silver stone and the red curtains you see the blond lady sitting there in the corner, with two pins pinned to her head. You are shocked. Straight away, you think: is she dead or alive? Then you think of Laura Palmer or remember your best friend from home who has the same hair color. You take two more steps and you discover it is just a blonde wig on a model head. Then you go over the props in the theater department and you find Agent Cooper’s original tape recorder, an amputated ear from Blue Velvet, or a severed finger of a lady who got robbed in an elevator back in Sofia; the robbers couldn’t remove the golden ring from her swollen finger, so they had to cut it off.

Borjana Ventzislavova, Who killed my butterfly, 2018, inkjet print on photo rag, framed, 120 x 80 cm

The next morning, when going down to the basement to do your laundry, you pass by a sign that reads “black lodge,” then another day you walk to town and you find a small shop in Banff which sells the two-heart “best friends” necklace. And while you are having this interview, ten meters away from you a lady with a costume in a zigzag pattern, the same pattern of the red room floor, is lying on the lawn…And so on and so on. In my Evidence series, I photographed a selection of all these objects, which seemed important to me during the process of following my intuition, again mostly in silver. I tried to create an index of all signs—as evidence of my reality-fiction scenarios, which are based on Twin Peaks and real stories and people.

Borjana Ventzislavova, Evidence #4, 2018, inkjet print on cotton paper, framed, 20 x 30 cm

Throughout the exhibition all sorts of correspondences and connections develop between different works, at times in different mediums, including visual and material correspondences.

Wahkohtowin. Yes, I truly believe things are related. And my works participate in these narratives of relations. Nothing is accidental, and this is always what my intuition tells me. Most of the time, my goal is to dive deeper into these relations, to reveal and understand them, and maybe sometimes to discover different perspectives on how things may relate beneath the surface.

While you address important cultural matters, your exhibition is also seeded with personal memories and experiences, for instance the neon “Als das Kind Kind war,” as well as with other references, including Leonard Cohen and Boris Buden’s writings on post-communism.

Absolutely! I used to forget a lot, especially names and titles, but if I remember something—fragments of texts, lyrics, quotes, whatever—then I know it has something very important to remind me of. I read Boris Buden’s The Zone of Transition maybe 7-8 years ago, and this one aspect of the child-parent relationship during the transition period of the so called post-communist countries and the Western world stuck in my mind. This moment of merging of these two worlds on both sides of the Iron Curtain back then, which still don’t always appear to be a genuine union, has somehow so much to do with the behavior of the parent telling the child how and what to do in order to become an adult, and the child who’s trying to fulfil the parent’s expectations without asking if this is the right way to go. The division of the world in two blocs felt like past history for a long time, but unfortunately with the war in Ukraine we see how absurdly and quickly things can regress. We don’t want to go back in time, but you see “Als das Kind Kind war” (which is a verse from Peter Handke‘s poem “Song of the Child” in Wim Wenders’s movie Wings of Desire) is a work dating from much earlier and which then found its exact place in this installation because of Buden’s text and thoughts on political and social transformation. And not only because of personal memories from watching the movie in the late 1980s and repeating incessantly “When the child was a child, it didn’t know it was a child…” but perhaps also because the child is sometimes more excited and doesn’t lose so easily the sense that everything is related.

And yes, such crossovers from assembled cultural references, personal memories, stories, and histories, play a most important role in creating these works for the show, and then again, here they come together in a flow to keep some balance and hint at my spell: “Water walk with us,” not Fire.

Your exhibition is animated by all sorts of ideas, yet it is also multisensory and acutely visual. To me, it feels very immersive and also like a voyage.

Thank you, this is what I try to do with my works, to travel with them while creating them and to travel means for me learning, experiencing, and enjoying, and when they are done to let the viewer to go on that voyage.

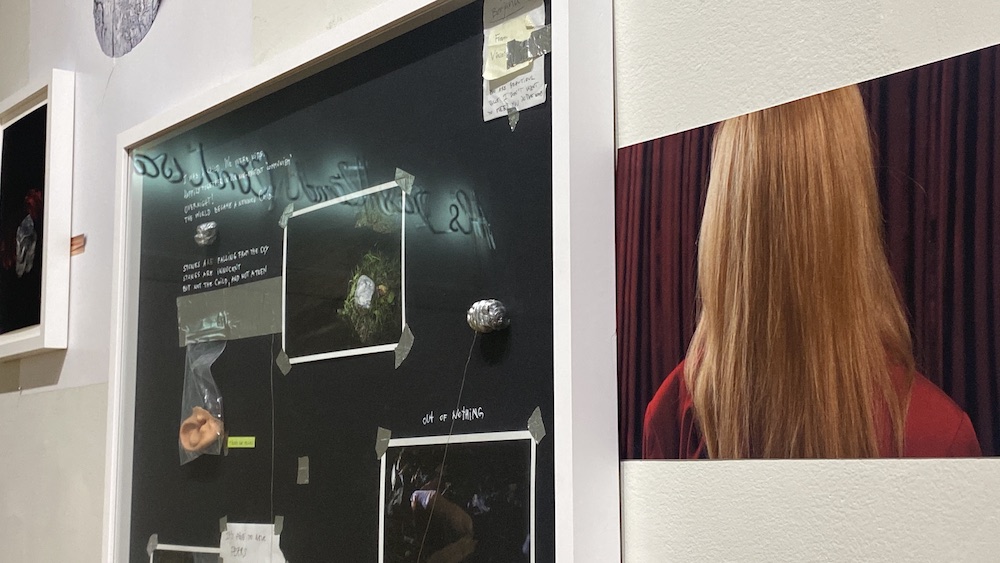

Borjana Ventzislavova, Ten Peaks or Water Walk with Us (installation view Radiator Gallery, detail 2022)

Walter Robinson in his studio, photo by Marina Tychinina

Interview by Devon Dikeou

Let’s start with your show at Air de Paris, “C’est le destin bébé” . . . It is like a great “best of” album . . . It had pulp romances, a Vietnam scene, a burger, cash and a salad painting . . . And a series of button-down, folded shirts . . . How did you edit the selection . . .

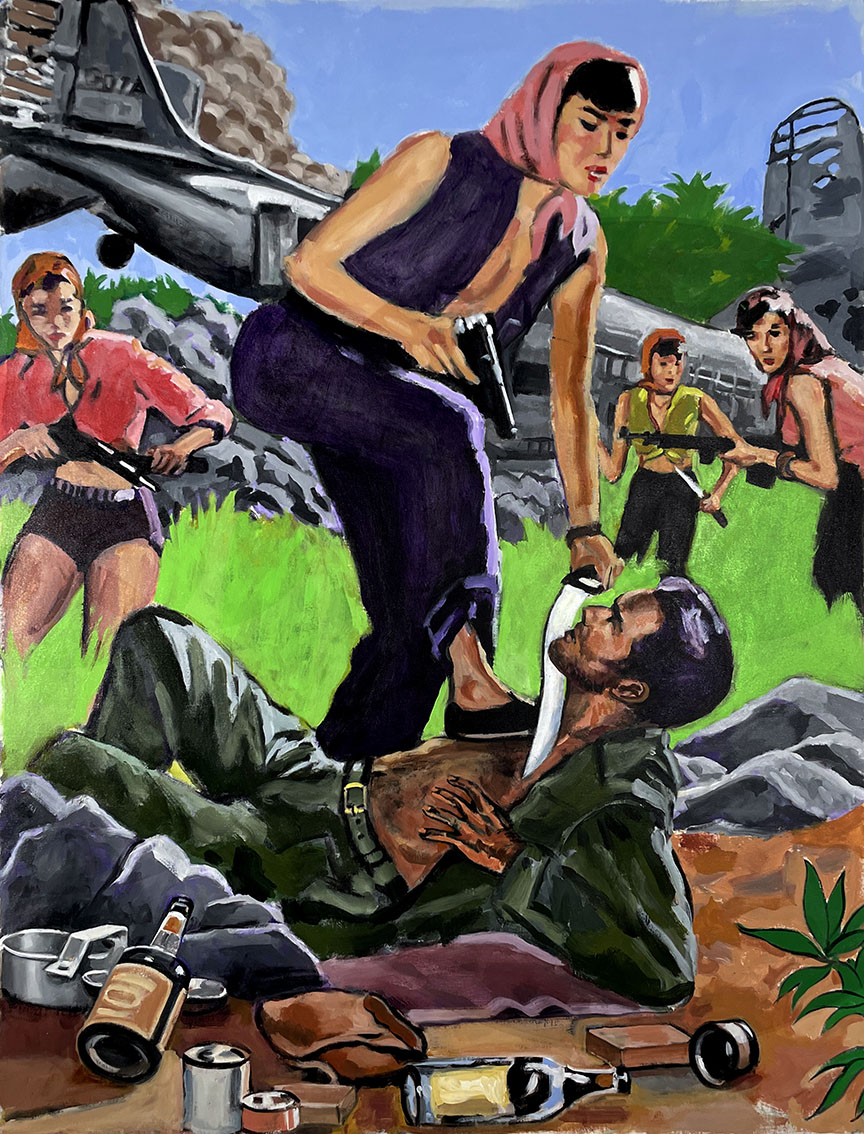

The dealers at Air de Paris, the legendary Edouard Merino and his partner Florence Bonnefous, made the selection from inventory. They’re awesome. They took some works on paper too. The new gallery space, in a development in the Romainville suburb, is beautiful, and their installation was sublime. They took my first colonialist painting—it’s a new series—which is six feet tall and shows a female Vietcong soldier holding a bayonet to the throat of a downed US flier, to FIAC and sold it. Art fairs sell art!

Vietnam, 2021, acrylic on canvas, 80 x 60 in, courtesy Air De Paris

Why shirts . . .

You know the shirt paintings? I first showed a few with Kai Matsumiya on Stanton Street, then did a solo show of 28-inch-square versions at Charlie James in L.A. Beth Rudin DeWoody bought one; she single-handedly supports the art market. I was psyched when Air de Paris wanted a bunch of them—the French have a thing about fabric and art— Supports/Surfaces, you know? I have long raps about all of my series, you really want to hear it? OK, try this: I paint a lot of sexy girls, in the studio I’m surrounded by images of women—you know, no one is really interested in men as a subject, not men OR women. But I felt bad, I don’t want to seem a complete dog, so I needed a masculine line, for balance.

So the thing about the shirt paintings, is that they’re MEN’S shirts, so they’re male paintings. What’s more, the images come right from the catalogues, or more typically from advertising emails, and the shirts are all flattened, folded and squared off. They’re pinned down, baby, can’t move at all. They’re just torsos, figurally castrated! Funny, no? Oddly enough, these days the clothing merchants have stopped advertising shirts that way, all folded and pressed. Now they picture them loose, as if worn by an invisible man, or even on a model.

Want more? Here’s a partially coherent text about the series that I wrote a while back:

The shirt paintings are about abstraction, the kind that Marcia Tucker featured in “The Structure of Color” at the Whitney in 1971, a show that included artists ranging from Rothko and Newman to Noland and Stella. It was an exciting exhibition, just about the first and last to survey structural abstraction. My shirt paintings are a way of joining that club, taking part in that spiritual quest, joining the ineffable world of magical color and structural form, while at the same time making a little joke about what is after all a bit pretentious.

So, the shirt paintings are poised on the threshold between the spiritual and material worlds. If you think of it, it’s nutty, dressing in abstract patterns, checks and dots and plaids, so popular and so commonplace, geometrical patterns that in addition to serving a mundane decorative function also signal some kind of cosmological order. Polka dots imitate the heavenly cosmos. A plaid may not reach to a heavenly gyre but it certainly can indicate an ancient genealogy. It’s an atavistic anthropology of dress.

The shirt paintings are an extension of my “normcore” series, which are paintings based on images taken from department store ads and mail-order catalogues—models and such, posed to sell the clothes they’re wearing. My models smile at you. Who does that? This kind of material comes already designed for visual appeal, and already calculated to sell. I don’t have to do it! What a relief.

Typically normcore works partake in various ways in what I like to think of as the consumerist utopia. We live in a world filled with resentment, racism, stupidity and hate. The consumerist utopia sells us on the idea that a better world is possible. All you need is a little dishonesty.

That’s such a long answer. I have much more. You know Lands’ End has a “Friends and Family” ad that shows a lineup of four women, two men and four kids. It’s secretly polyamorous! All white and blonde, my people.

Oxford Dress Shirt Lands End, 2016, acrylic on paper, 12 x 9 in

For that matter why any of the series . . . Is it always sex and death with you . . .

Not so much death. Though I have a great artist portrait taken by Marina Tychinina of me lying flat on my back on my studio floor, clutching my heart like I had an attack.

There’s a famous story of you getting a six pack of beer going to the studio and maybe having a few, and painting it, similarly buying a Whopper and taking it to the studio and enjoying, then painting it . . . Both the beer and the burgers became series or parts of series . . . talk about series and serial.

Not famous just a little joke, from the ‘80s, when I was still drinking. I’d buy two six packs as still-life setups, and start drinking and painting at the same time, so the pictures would end up depicting only four or seven bottles or cans. It was a literal search for the spiritual in art.

It was a color exercise as well—burnt sienna (Guinness), cadmium yellow light (Miller), permanent green (Heineken), and red, white and blue (Budweiser). And once again, the object’s appearance had already been maximized for market appeal. Big beer clientele, I figured. Painted them on chipboard and sold a ton at $50 each.

Two Six-Packs (Heineken), 1983, acrylic on chipboard, 20 x 30 in

And that’s before I read your recent catalogue, “Works on Paper 2008-2020”. . . A groovy catalogue aptly titled just that . . . Are the works on paper studies or independent works . . .

I put that together myself, in a burst of initiative during the pandemic. It’s a sampler of all my series, of which there seem to be many. A kid named Erin Knutson did the design and handles the printing; she’s brilliant, Elle Decor just hired her. Richard Prince let me put Fulton Ryder as publisher. And Sarah Nicole Prickett wrote an awesome fiction to serve as the text, about a male artist who has a visit from a critic writing a review, but the artist murders the critic and writes and files the review in her name. Didn’t really happen. The mag is officially distributed by Printed Matter. I have to bike over 15 copies tomorrow.

And these series are painted from real life, in plein air . . . The pinup girls or harlequin covers those would have to be painted from source material . . . No? Please talk about the differences . . . Both in the physical sense of painting and constructing a painting . . . And what then the painting evokes.

No no no it’s all faked, I paint from projected photographs, in the dark. Painting in the dark gives the best art effects. It’s all from media sources, or photos I take. Basically, I have no imagination or skill, don’t tell anyone. I just pass things along, things that want to be fine art.

Kill for Me, 2021, acrylic on canvas, 24 x 24 in

Now the candles, does the candle expire before the paint is dry, or the other way around . . .

Candles are supposed to be mystical, otherworldly, spiritual, you light them to god in church, they mark religious devotions, ceremonies of life and death. Richter paints that kind of candle. All my work is about desire. My candles are carnal, not spiritual. They’re stock images that Asian massage parlors use to set the tone in their ads. They’re about the senses, about touch.

Speaking of burning candles, as your work came of age in what we like to call the Pictures Generation . . . Place yourself and your work within that context then and now . . .

I’m an ‘80s artist and proud of it. I started painting copies of pulp paperback covers in 1979, and had my first show at Metro Pictures in 1982. The brilliant Helene Winer just called me up and asked if I had anything to show. I knew her from the ‘70s, when she directed Artists Space, one of our hangouts. It was next door to our loft on Wooster Street.

Spa Candles, 2018, acrylic on canvas, 36 x 36 in

And since we’re interviewing you within the context of zingmagazine . . . Let’s visit your history beyond the canvas, in the role of the art critic, writer, editor, publisher, raconteur . . . As a prolific writer critic at Artnet years you were trailblazer of how art is reviewed, disseminated, and consumed in the then new realm of internet publishing . . . How if at all, did that effect your art practice . . . And of course, your writing practice . . . Your viewing practice . . . Your critical practice . . .

The art world loves writings by artists, but great artists who are good, practicing critics, that’s fairly rare. Fairfield Porter is perhaps the most famous. I usually joke that a critic’s job is to be an expert on everything, while an artist’s is an expert on one person, themself.

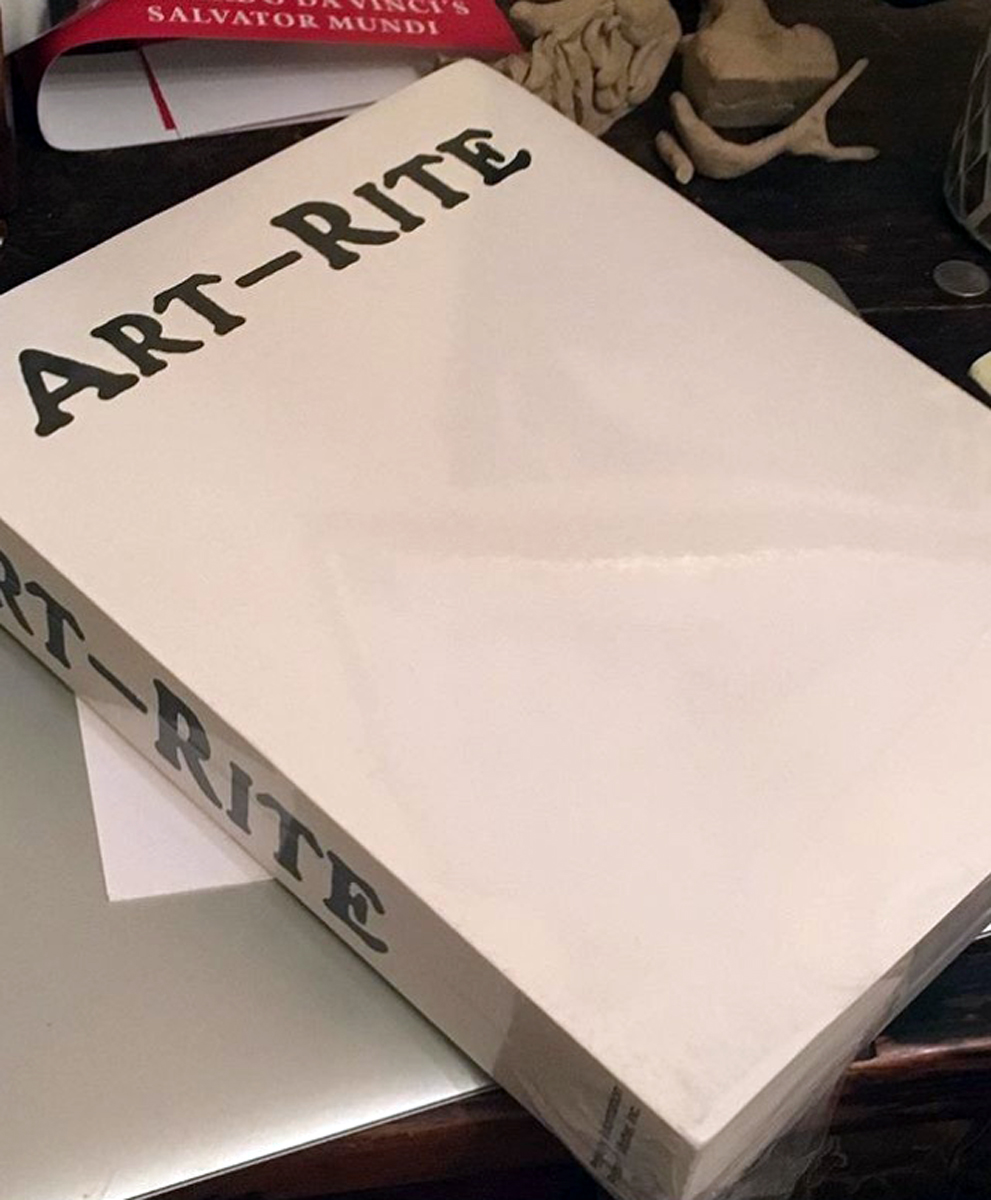

And you’re a founder of Art-Rite, ‘73-‘78, the name sounds so ‘70s , like Diet-Rite . . . speak about founding/publishing that . . . What are some of the memories both fond and otherwise that fuel your recollections of an incredible time capsule . . . As all defunct or sleeping magazines eventually become . . .

Art-Rite we did in the ‘70s. Kids in their twenties can do anything. We were populist, whereas most art mags—not yours!—are snobby. David Frankl wrote an astonishingly friendly report on the mag in Artforum years ago. Now Art-Rite been collected into one huge tome by Primary Information, the publisher that specializes in such exhumations. It has no index, so you can’t simply look up your name, you have to read the whole book.

When the East Village art scene blew up in the early ‘80s, I got a job as art editor at the East Village Eye. We had a scandal, Waltergate, the details of which I will spare you; a hack artist yelled at me for reviewing his show merely by looking in through the gallery plate glass window; and I wrote the only contemporaneous review of Richard Prince’s Spiritual America show on Rivington Street. And I met so many great artists, Mike Bidlo, Keiko Bonk, Luis Frangella, Steven Lack…and Carlo McCormick, the lowbrow art expert and nightclub celebrity. I was his driver.

At the same time I had for years a part-time job compiling art news for Art in America. I wasn’t a reporter—in fact I hated phoning people up and asking embarrassing questions—and knew nothing about the art world or anyone in it. A typical art mag hire: if the kid is dumb enough to want the job, it’s his!

My big break as an art critic and editor came in 1996, when I was hired to run my own show—Artnet Magazine. The digital revolution changed my life. I wrote so much. It’s insane. And it’s all still online, if a little difficult to find. I unleashed the great Charlie Finch like a loose cannonball onto the rolling decks of the art world. I think today Mary Boone still thinks I’m him. And I published Kenny Schachter’s first episodes of his Art Dealer’s Diary. He’s gotten so much better at it.

I did that for 16 years, then Artnet shut the mag down. What a boon for me! Why had I been sitting in front of a computer all that time, an easel is so much more fun. Now my art career is on fire. But I don’t regret my white-collar days at all, especially when it comes to Social Security. Thanks to those taxes they took out of my paycheck, no matter what, I get a fat direct deposit from Uncle Sam every month, enough to live on if push comes to shove. Don’t touch my Social Security!

Even though the awards season has passed, one last question . . . House of Gucci or Spencer . . .

Jeez, I dunno. Lisa makes me watch “Grace & Frankie” endlessly. For octogenarians, they sure drink, drug and hook up a lot. Something to look forward to.

proximity detail at FOYER-LA photo by Josh Schaedel

FOYER-LA is headed into its third year of small-scale but provocative exhibitions—ranging from the first Los Angeles show for James Rose to new perspectives on Maya Deren. The current show, “Proximity,” an installation by founder Connie Walsh, explores the possibility of intimacy and community in our fragile post pandemic world.

Interview by Jane McFadden

Foyer LA has been open since 2019. Tell me a bit about the space and its goals.

I see it as an experimental exhibition space that expands the work that is happening in the studio into the community. I began by inviting in friends and colleagues from my life in the art world; the first show was quite big with eight people—artists that took a leap of faith about the space and went for it. There has been one other group show, but mostly the projects are one or two artists around a fairly abstract theme. I am interested in solo projects that activate or responds to the architecture, or that haven’t been seen prior, in something that can’t exist in a studio, and maybe needs the space. I like to think about how I might layer one project onto the next, having an artist respond to a possible residue left by another. I’ve invited outside curators, as well as writers. I often invite the artists to speak about their projects in casual discussions. I want the space to keep growing and keep shifting in its possibilities—the pandemic certainly demanded that. I also try to use the space for other kinds of activities and events—usually generated from the artist— a botanical ink dye workshop, an Ikebana workshop, a clairvoyant tarot and sound odyssey.

When I was back in Maine this past summer I visited the South Solon Meeting House built in 1842 and I was fascinated by its continual existence and that it is still being used openly and without the exchange of commerce. I want to see FOYER-LA as this kind of ‘free’ space—open to possibility and allowing for the development of a thread of thought.

So how has this project space informed your sense of community?

That’s an ongoing challenge. The issue of what constitutes a community and how it is formulated and how it is generative is of interest to me in general. Recently I was fortunate enough to be able to go back to Skowhegan a second time and I was aware of that question for myself; I was fascinated by practical and tactical mechanisms of how that community works, like how they gave us breakfast so we had to be on the same time schedule despite whatever jetlag, and so we had to start our day in proximity. We all know that collective meals encourage relationships to form, but it’s so true. I also give credit to the teachers for their incredible generosity; they exemplified such an inspiring humanity in such a challenging time (summer 2021) that you wanted to rise to the occasion and do the same; but community is definitely harder to build in a large city outside such an environment. I’ve been making art for a while, and artists often complain about the system. Many artists are trying to offer different ways to interface with art and I am interested in that as well.

Certainly, the intensity of Skowhegan partially comes from the commonality of the chosen path as artists. To me so much of that experience was about the gift of time—to commit, to slow down, to open up, to share, and to exchange. Yet it isn’t isolated unencumbered time; it is the people (artists) bumping up against one another—each engaged, each finding their way. I keep thinking about the word potentiality. Somehow my time there, both last summer and 25 years ago, allowed me to feel a part of something larger than myself. I think this drives my interest in the space and in my work.

Fire pit preparation, Skowhegan, Maine

In the current show, you make a specific architectural intervention into the space. Could you please describe it, and does it function as you expected it would?

I built a raised plywood floor that is fifteen inches above the existing floor; so as soon as you step into the space you are on this construction grade subflooring. In doing so, I wanted to immediately activate the viewer and make them aware of their own presence in the space as a participant. The choice to raise the floor was based on my wanting the ceramic pieces to be in dialog with the photographs without isolating them on pedestals. So really in the show you are standing on a kind of platform pedestal, with the sculptures.

proximity at FOYER-LA, photo by Josh Schaedel

I found the pairing of the ceramics and photographs (and the triangulation with the raised floor) brought out a different sense of each medium and its material potential. Was that the dialog you wanted to produce? What was the experience of working across these media in preparing for the show?

These photographs were collected over a few years, then selected, worked on, and printed; whereas the spheres are made on a potter’s wheel. When I’m working on those, I’m looking down; I’m pulling clay into an open cylinder and then I’m closing the cylinder on the wheel; so what I look at, what I see in the process, I then obscure. I often weirdly wanted to get inside the spheres when I was making them. In fact, not until the end of the process, until I installed the show was I okay with being outside them. They are very private, intimate, enclosed, like a hidden secret in a physical form. They have this presence—like children. But the photographs are of another time and space. And the floor brings it all together. The floor creaks; there is a give; it is hollow underneath (a trapped space which in some ways mirrors the sculptures). There is a question of access in the photographs as well. What happened in the spaces around the image, or in the time prior or after the image—these are hidden secrets too.

The color of the vessels is similar to that of the floor and at times they seem to float. I also chose to hang the photographs low, more towards the height of the actual floor, so it shifts a response, maybe to your gut rather than your head. Their position on the walls has this intuitive weight for me. Similarly, the orbs were originally hand-held and then I wanted to make them larger so it was almost like you had to hold them in your arms.

Just a few of the orbs are black, and this seems to represent a slightly different process.

Yes, these are a bit of a tribute to Skowhegan where a few of us got together and did a pit firing. Used banana peels, coffee grinds, used tea bags, sodium, copper and silver coins were all wrapped around the sculptures in tinfoil and we then threw them into the fire in the pit. It was interesting in terms of community. We had to dig a hole almost like a grave; it took a few of us (some of whom were just digging to help for a bit). Then we built a fire and we placed our work in the fire and we would have had to tend to it and watch it all night, but we ended up covering the hole with a steel plate, which probably caused the excessive blackening, because we got the fire really hot and it didn’t have a slow build up or cool off. For me it was helpful to have to let go of any expectation. I’ve learned in general as an amateur ceramicist to let go of any attachment, to let go of the preciousness that comes out of object making. And last summer I was also letting go, as so many of us had to do on so many levels in the past few years. Some vessels broke in the fire; some broke being shipped back to LA. I felt they really needed to be present for the show. They bring that fire into the show.

proximity—detail at FOYER-LA

The photographs in the series cover a lot of geographic ground, which was so poignant on the heels of our shared global lockdown. First please tell me your thoughts about travel in your practice; and then in turn, how did the pandemic affect your conception of the show?

I intentionally chose not to title the works to give any sense of where the images are from. They are also cropped tightly and don’t give much of an indication in the image either. It was not to be vague and abstract, or to try to disassociate the viewer’s desire to locate or know. I think it’s just about a moment; they feel to me to be about a spatial moment. On the long wall I played with the possibility of a larger implied narrative between the images—reinforcing the tension or support in the images through the placement of the images in relation to each other horizontally and vertically; so that the weight of a vertical stone wall is metaphorically the tension within a stormy sky.

I never know if the moments I photograph are going to lead to a piece. Initially I didn’t see the photographs and the sculpture together but then I realized I was doing the same thing in both of them. I also thought the series was going to be more ongoing; but the pandemic and Skowhegan helped me come to the formulation of this project; the isolation of the pandemic and the isolated time at Skowhegan away from daily life brought the show together.

You said that the photographs are about a spatial moment—is that moment one of proximity from the title of the show?

Yes. I have been thinking about proximity and how little we all have experienced beyond our immediate family or friends these past two years. I am interested in both a physical proximity and an emotional proximity and how it involves a certain present-ness.

proximity—untitled 13 at FOYER-LA

Do we want to hold these moments in our hands like the spheres? Because I really want to hold those spheres.

I think you want to access the moment; I think you want to get in there, to locate oneself. Maybe the scale and presence of the sculptures—and sharing the space with them—helps slow things down a bit. I see them kind of settling us all a bit, and then you “sit” with the images.

Can I ask you about parenting? There are these vessels which you briefly related to children; you mentioned a daughter reading poetry in FOYER-LA; there is a boy in one of the works who I happen to know is your son, next to your daughter. I know you traveled with your children. You obviously aren’t hiding this content, but it’s not foregrounded either: how does it figure in your sense of your practice now?

Most of the photographs were taken when I was traveling with my children; but I think the preciousness of that documentation is only evident to me in hindsight now. It wasn’t that I was trying to capture an experience with them—they usually aren’t visible in the images except the one you mention. I chose to include that image (my daughter with her back to the camera and my son in the background in soft focus on the flooded streets of Venice) hesitantly. Maybe it was private—maybe a kind of tribute to them and to the weird phenomenon of the streets of Venice being flooded. But I think it clearly depicted what these other more abstract, more formally considered images are doing: my daughter is moving forward yet away; the two figures are separate but connected through the viscosity of the water; the corridor is tight; and I guess for me it feels like interconnectedness across distance no matter what. It is a metaphor for their relationship as well as what is happening in the show.

Well that in of itself is a bit different than what we might expect from highly produced postwar photography that often seems to organize world into a series of untouchable spectacles and typographies. How do you relate to that history?

The images are not for me a representation of a specific place. They are material for the possibility of connection. Often in the images it feels like some sort of intimacy just happened or maybe is about to take place. There is the residue of a possible exchange—a disoriented cushion, flowers to be appreciated, a couch to lie on.

I agree, some of the photographs are sculptural; and the floor, framing, and hanging insists upon that even more. Why do you think you turn to photography in your sculptural practice?

While in the studio at Skowhegan I listened to a lot of recordings of past artists’ lectures. In one of them Roni Horn spoke of presence being more than what you see. Does presence involve the suspension of time? I think about how time sometimes feels like it has stopped when you are with a good friend, or experiencing nature, or whatever it may be. I think I’m trying to create a site for connection, for momentary presence.

That reminds me of the way you described FOYER-LA at the beginning of our conversation.

Yes—a space to move through, a place where you transition. It is an experiment to share with an audience that hopefully becomes a community.

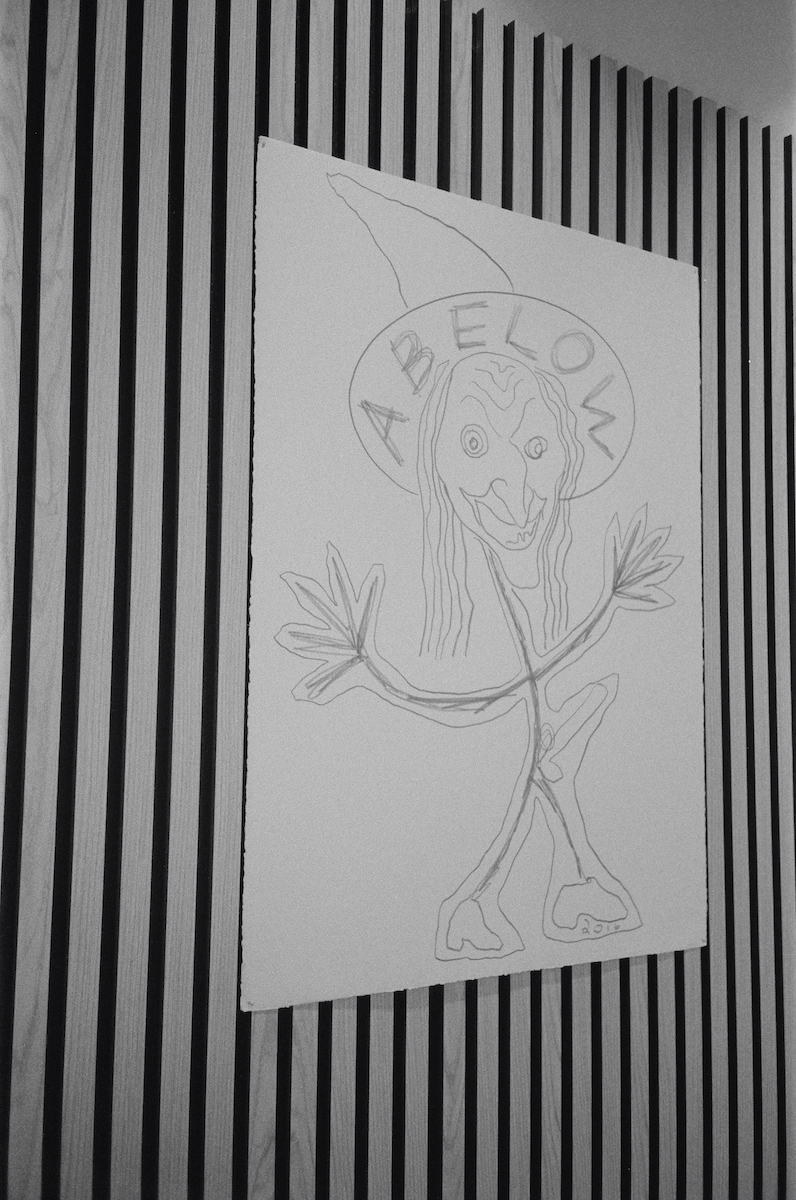

“Zoom” at Jir Sandel, Copenhagen, Denmark

Joshua Abelow’s output has been multifarious—from writing poetry and prose to blogging, along with running a gallery called Freddy, first in Baltimore, then upstate New York. But at heart he’s a painter. Abelow’s paintings can be both satirically autobiographical while engaging both with the history of painting and the materials themselves. His practice also includes drawing, which can also be diaristic in nature. His work has been showed widely and is most recently manifested by a roughly simultaneous five gallery presentation of his work, spanning from his childhood beginning in 1982 to the present, all now on view in locations from Omaha, Nebraska to Copenhagen, Denmark, along with the more usual suspects of New York and San Francisco, and last but not least Providence, Rhode Island, where he received his BFA in Painting from Rhode Island School of Design in 1998. His project “14 Paintings” appeared issue #24 of zingmagazine. And his series “Call Me Abstract (Self-Portrait at Age 36)” is part of the Dikeou Collection.

Interview by Devon Dikeou

In the ‘80s I must have read in a Koons interview something like all his works were editions of three with one artist’s proof . . . He said he learned this system from Stella . . . Someone whose knowledge and example Koons might have been eager to follow (Stella was just closing his second MoMA retrospective and Koons had just opened his “Banality” show). The idea being that he’d make one for New York, one for Chicago (LA wasn’t on his radar yet), one for Köln, plus one artist’s proof . . . Essentially, the same show in three places . . . I’d say you’ve got a world-wide Abelow-palooza art style tour going on . . . Talk about the differences between your five shows . . . ‘Cause I’m guessing the playlist isn’t the same in all five venues . . .

One thing that was unexpected (to me, and I think everyone else involved) is the way it all just came together without too much forethought or effort. I don’t remember which opportunity came first—Jir Sandel or Baader-Meinhof—but they happened around the same time. I think that energy then overflowed into the exhibitions at Apartment 13, A.D. NYC, and Et al. There’s so much artwork involved in these exhibitions that it’s sort of hard to talk about.

The show in Copenhagen—the gallery, Jir Sandel, which is a great name . . . And the title of your show there . . . “Zoom” infers the opposite of transitory, rather it’s a word that conjures isolating, whether it’s in reference to a camera technique or the app for communication, now so much a part of our pandemic vernacular . . . Please speak about the show in Copenhagen . . .

Jir Sandel is an artist-run gallery without a fixed location. The name and logo design refers to Jil Sander, the German clothing design company. The Zoom show consists of three witch pencil drawings—one made in 2013 and two made in 2016. The main focus is a group of 12 x 9 inch oil paintings that I made in 2020 just as the pandemic was hitting. All of the paintings are abstract with gestural marks and layered paint application. These paintings came just before the work I made for Leaky Abstractions at Magenta Plains (2021), a computer science themed two-part exhibition. Zoom is not presented in a typical white cube—it’s happening in the office space of an electrical company and is open by appointment only. The show is documented with black and white 35 film using a “very old Olympus model” and this too is a specific choice. We used an excerpt from an essay by Boris Groys to frame the show, “The standard white cube is a thing of the past. And that means that the curator has to find a specific form—a specific installation or configuration of the exhibition space for the presentation of digital, informational material. The question of form becomes central once again. However, it shifts from the individual artworks to the organization of the space in which these artworks are presented. In other words, the responsibility of giving form is transferred from the artists to the curators who use the artworks as content—this time as content inside the space created by the curators. Of course, artists can reclaim their traditional form-giving function, but only if they begin to function as curators of their own work.”

“Joshua Abelow featuring Joshua Boulos” at A.D. NYC, New York, New York

“Joshua Abelow featuring Joshua Boulos, A.D. NYC” . . . Could you elaborate on this relationship . . . You were JB’s mentor in a way . . . at RISD right . . . True collaboration or two-person exhibition . . .

I met Josh Boulos in Brooklyn at the opening of a show I curated called Freddy’s World back in 2019. At that time, Boulos was a RISD student doing his undergraduate work in Painting. We stayed in touch and in 2020 I did the Weird Science show at the gallery he founded in his apartment with his partner, Baijun Chen. I was really happy with the way that turned out and we’ve all just stayed in touch, etc. I’m showing four E.T. Paintings that were made right at the end of 2021 and one drawing that also features E.T.. Each painting is 35 x 70 inches and the drawing is 30 x 22 inches just like every drawing I’ve made since 2004. The image of E.T. is based on a drawing I made of E.T. in 1982 (when I was five), the year the movie came out. In getting things ready for the show at Baader-Meinhof, which includes a number of my works from childhood, I found the E.T. drawing in an old sketchbook and I got inspired. I often recycle motifs and images in my work and the idea of breathing life into an image I made as a little kid was weird in a good way. Boulos has two small sound-based sculptures that use Deadmau5 as subject matter and inspiration.

“Joshua Abelow: 2022” at Apartment 13, Providence, Rhode Island

Speaking of RISD, the Providence gig at Apt 13 . . . you first showed there during the pandemic, and Apt 13 is the brain child of aforementioned JB . . . The show is titled, “Joshua Abelow: 2022” so I’m thinking this will be new work . . .

Josh and Baijun moved to a sizable apartment with multiple rooms. My show is happening in what is normally their bedroom, but they gave it up for me to do this little presentation. The show consists of six small paintings hanging on a pink wall with a green rug on the floor. All of the paintings are abstract and all are from 2022. They relate to the paintings at Jir Sandel, but are also a bit different . . .

At Et al, in San Francisco, the show is titled, “Anti-Magic” and you share the stage with Dani Arnica . . . Speak about this . . .

Dani Arnica is a young artist based in NYC. We met upstate at my church a few years ago and have been friends ever since. She’s also my studio assistant and is helping me run Freddy this year. At the very beginning of 2021, Dani had a show in the bell tower of Freddy called Evil Moon at Freddy’s Bell Tower. Anyway, we are close friends and artist comrades so this opportunity is very meaningful to both of us. The concept of the show is based on an excerpt from a book by Jaron Lanier called Ten Arguments For Deleting Your Social Media Accounts Right Now. Lanier writes, “You can make your own consciousness go poof. You can disbelieve in yourself and make yourself disappear. I call it anti-magic.” Dani takes center stage in this exhibition with a handful of medium-sized “chalkboard” paintings. My contribution is a selected group of 12 x 9 inch “dot” paintings and one self-portrait drawing.

“Anti-Magic with Dani Arnica” at Et al., San Francisco, California

The big kahuna is in Omaha at Baader-Meinhof . . . The checklist alone is something like 144 pages . . . How did you prepare for this, your Mid-Career Retrospective . . .

I became aware of the gallery about a year ago because Eric Schmid curated a show that included a drawing that I made in collaboration with Joshua Boulos. Shortly after, Kyle asked me if I’d like to do a solo show. He said he wanted the exhibition to be “truly unique” and he encouraged “experimental ideas.” I suggested the idea of a retrospective that would include childhood works and he liked that idea so we rolled with it. The planning that went into this exhibition was about ten months in the making. It basically started with me sharing a vast amount of digital images with Kyle and we just started shooting ideas back and forth for months. In the end, I drove a 15-foot Uhaul out to Omaha with about 160 works. Once in Omaha, I edited down the works to a total of 60 paintings (not including the stuff from childhood). 36 of the 60 paintings are 12 x 9 inch paintings hanging in a grid on the second floor. All of this is to say that the preparation for the show was both strategic and intuitive.

Are you showing only paintings . . . You sometimes have other performative elements like songs, poems, even drawings . . . How do they figure in the mix . . .

The exhibition features adult paintings from 1995–2022 and childhood paintings and drawings from 1982–1994. I think of the show as a performance in and of itself—nothing additional is called for. I was born in 1976 so there is obviously some humor in featuring works from the eighties.

The gallery’s name, Baader-Meinhof, implies constant exposure . . . And omnipresence . . . Funny it’s in Omaha . . . The middle of the country . . . Not exactly corner of main and main in terms of many things including the microcosm of the art world . . . Although some would argue Omaha, home of Warren Buffet, is the center of something. . . Speak about “centers,” middle, and the specter of influences . . .

This is what’s on the gallery website:

No, the gallery bears no personal or professional affiliation with the Red Army Faction.

The name is a reference is to the Baader-Meinhof phenomenon, a term which refers to frequency illusion, a cognitive bias in which, after noticing something for the first time, there is a tendency to notice it more often, leading someone to believe that it has a high frequency of occurrence. When we discover something new, we begin to imprint the significance of our revelation upon the world around us.

I see a relationship between this phenomenon and the ways in which culture is produced and reproduced, coded and canonized. Cultural discourse is often dominated by the fetish of the new and undiscovered. In this context, Baader-Meinhof phenomenon feels like the harbinger of the subsequent process of cultural sublimation and recuperation.

Running a space “off-center” demands a decentralized approach to sharing and community building. Most of our audience finds and experiences the work we do through social media or online. As word trickles out, spreads among friends and colleagues, Baader-Meinhof, the art gallery, manifests the phenomena it is inspired by.

“Joshua Abelow: 1982-2022” at Baader-Meinhof, Omaha, Nebraska

A lot these shows are in artist-run spaces . . . It’s an interesting choice in that I feel the organic nature of artist’s projects fosters a commingling of practices, platforms, mediums . . . An open mic so to speak . . . And mentoring . . . And Freddy . . . in a way these kinds of spaces are the “influencers,” rather than spaces imbued with the aura of establishment . . . But both are good and important . . . Thoughts . . .

Couldn’t agree more. I’ve always been a huge advocate of artists’ advocating for themselves. There is so much potential for the role of the contemporary artist to go far beyond creating or taking objects and placing them in rooms. I’m very interested in Relational Aesthetics and, for me, working with artist-run spaces is generative because they understand that curation is a form of artistic practice (as opposed to a way of generating capital).

I met you in Ross Bleckner’s studio in Chelsea during the “spring fair season” . . . You were having an open studio, a lovely consequence of working for Bleckner . . . But at that time you were working on your own stuff, a series that eventually made its way to the Dikeou Collection . . . It’s called “Call Me”, which featured some 30-odd paintings, your age at the time, with your phone number emblazoned on each one . . . All the same, but different and repeated over and over and over . . . Please expound on repetition . . . Did you screen, do you still screen . . .

Yes, yes—I remember meeting you! I worked for Ross from 1999–2006. In 2011 and 2013 he let me borrow his Chelsea studio for the summer. In 2011, I used the space to present a series of Art Blog Art Blog exhibitions that were primarily curated by artists and DIY spaces. In 2013, I used the space to make the work for my Abelow on Delancey show at James Fuentes. I believe we met at that time. The piece is called Call Me Abstract (Self-Portrait at age 36) and it consists of thirty-six 12 x 9 inch yellow geometric paintings with my New York cell phone number painted in black on top. Each one is individually painted— no screening or stenciling, etc. When I was in graduate school (2006–2008), I became influenced by Bruce Nauman—his humor, pathos, and exploration of repetitive tasks, particularly in the early works, was extremely impactful to me. I wanted to bring some of those ideas to painting. His 1968 piece, My Name as Though Written on the Surface of the Moon, opened up my thinking about self-portraiture and what it can look like.

And at that time you had a blog “Art Blog Art Blog” that in a way predated the omnipresence of the blog now. “Art Blog Art Blog” lasted five years, and was, some would argue, a definitive chronicle of that period in the art world . . . A “scene and heard” from the perspective of . . . You and the many roles of you; you represent the artist, the curator, the critic, the lover of music, the poet, the vociferous manic man of drawings, the fan, the influencer . . . You cite Nauman as impactful on your thinking . . . For me Kenny Goldsmith . . . Even Sean Landers . . . Also come to mind . . . Maybe because of the unrelenting ongoing nature of the project . . . Is that why you made it, the blog, “Art Blog Art Blog” have a finite ending . . . And as result the monster/blog becomes a caged physical sculpture . . . Talk about the history of the blog and transition from the digital platform to literal object . . . And then downloadable for free . . .

In 2006 (the year I got to Cranbrook) I was so frustrated with the limitations of a traditional painting practice. Nauman was the perfect artist to lead me out of that closed loop. The blog, which I started March of 2010, was directly influenced by Bruce Nauman and the idea of an expanded painting practice in general—Michael Krebber was also very much of interest to me at the time. My interest in Kenneth came a bit later, but yes you are very much on the money. Kenneth organized a show at Freddy back in 2015 titled, One and Three Tweets, citing Joseph Kosuth’s seminal 1965 work, One and Three Chairs. Very few people probably “got it,” but for me it was a big deal. Kenny and Cheryl (Donegan) came down to Baltimore for the opening and we had a great time. In terms of the blog—I just got tired of doing it and the rise of Instagram made it seem antiquated. I also didn’t like that people would refer to me as “artist and blogger”—the point of the blog was to be an artwork. Exhibiting the blog as a sculpture alongside large paintings in my 2016 Fuentes show titled Freddy was a victory in that regard, even if people didn’t really “get it” at the time. When I ended the blog in 2015, I replaced every single image with a Running Witch painting. The idea was that the blog would appear infected with a virus. The original version of the blog is accessible at the Los Angeles Contemporary Archive (LACA). They are working to web record the entire thing, to make it accessible on their site for viewing. It exists as a sculptural object in an edition of 3 along with one artist proof. Ideally, I’d like to have the blog accessible in other educational contexts for students or researchers.

The place/platform of words has an equal presence . . . In your art vocabulary . . . From Painter’s Journal to more recent publications such as, Relax, Contemporary Abelow Daily, You Make Me Happy . . . what kind of documentation/publication/catalogue/archive/platform can we expect from this flurry of activity culminating in your mid-career retrospective . . .

I think Jir Sandel is planning some kind of publication for the exhibition in Copenhagen. Not sure about Baader-Meinhof. It would be amazing to find funding to do one publication that features all five of these shows. We also want to find an appropriate venue in NYC or LA for the retrospective exhibition to travel. All five exhibitions are happening outside of the major commercial system, which I like as an artistic gesture, but funding is obviously an issue. If anyone is interested, Call Me.