Lucky DeBellevue is a Louisiana-born, New York-based artist most well known for his voluminous yet delicate, textured sculptures made of colored chenille stems (aka pipe-cleaners). Lucky has exhibited widely, including many one-person shows—most recently at John Tevis Gallery in Paris. Lately, Lucky has been focused on 2-D work, such as his collaboration with John Armleder for DISPATCH.

Interview by Brandon Johnson

We just published a project of yours titled Collaboration in the new issue of zing, #22. It’s one of the most printophilic projects of the bunch—xerox, collage, black-and-white, hand-cut, typewritten—all the qualities of a low-budget ‘zine. Do you have a history of ‘zine-making or is this your first go in the aesthetic?

I definitely wanted to reference zine making, but it was my first actual go at it. However, I have been planning to make a zine named “Choicez” for many, many years. I always had the cover mapped out in my mind, a sad hand-drawn font, a photo of a woman with a pitchfork I found in a book entitled “Weavings you can Wear”, but I never got around to actually making it. Now we live in a world of blogs, maybe I will finally make it that way, but I love zines, so maybe both? Probably never happen.

As you say in your curator’s note, the project involves a reinterpretation of documents from a scrapbook made by women prisoners convicted for murder in the South. You mix in images of your own work with newspaper articles letters, and forms to create a “forced collaboration.” Do you feel that there is a degree of affiliation with your work and the documents from the prisoners’ scrapbook or is it a more happenstance juxtaposition?

A little of both. I wanted it to be kind of absurd. After all, this was a record of these peoples’ lives in this amazing scrapbook, and I was being kind of a vampire, just plopping my work on top of it. So there is a bit of subtext about how one’s life can be used for someone else’s purposes, bringing attention to themselves by association. I also identify somewhat with their marginalized status. What could be more outsider than being a lesbian cop killer in the South in the 1970s? I still want to believe somewhat in the outdated romantic idea of the artist as outsider, so that is part of it too.

Your work, Otter, was recently installed at the Dikeou Collection in Denver. It is a large, teepee-esque sculpture made of your signature material, chenille stems. What first attracted you to this material and why have you continued to use it?

At first, I thought it was a kind of dumb joke. I was at a point when I wanted to clear my head and start from zero as far as my practice. I was thinking of the pop artists and how Lichtenstein drew from comic strips as a platform to explore other things. So I went with something that was very basic and memorable to me as a child, something I assume others had used in their arts and crafts classes as children or had some kind of experience with.

I don’t use chenille stems exclusively as a medium anymore. In the last few years my process has opened up to include other mediums. I still make some work with them, and use them in printing methods, but it isn’t quite as central to what I make as it once was.

You explained to us previously that otter was gay slang—something along the lines of bear. How does the title relate to the piece? Is sexual identity important to your work on the whole?

Originally this piece was in a show at the Whitney Philip Morris, and the titles of the works in the context of that show were important. But usually my work is untitled. I was interested in what goes on underneath the facade of appearances. The setting of the show was a public space attached to a corporate office, and I wanted the titles to reflect either the machinations of power through alluding to historical figures who grasped for it, or by using coded references that categorize interests within a particular community. So in this exhibition the titles functioned as objects kind of hiding in plain sight.

I was going for the trope of a sub-set within a set, and Otter refers to a kind of body type in the gay bear community, not the hairy/stocky/chubby/football player build that many of the bears fetishize, but a thinner body type that is either hairy and/or is self identified as being part of that community. Anyway, this sculpture entitled Otter is phallic-like, fuzzy, and becomes thinner as it rises in space. I wanted there to be some humor in the title, and the color gets hotter as it rises. While I think we should own what we are, I’m not so into being reductive about it. So usually I want titles to be more suggestive if there is one. I like that quote by Kierkegaard: “To define me is to negate me.”

In your artist statement, you say you consider Otter sort of as a drawing in 3-D due to its linear quality and gradations of color. Is this your approach to sculpture—through lines?

Mostly I was just thinking of using materials I hadn’t used before, just exploring. Initially I wanted to create a “thing” in the most economical way, so most of the earlier works were more minimalist, then became progressively more layered as my interests evolved. Part of it was a decision to make objects that were more porous and textured, not just flat massive surfaces that signified strength and stability.

What’s on your horizon?

In December I am in an exhibition entitled “December” curated by Howie Chen at Mitchell-Innes & Nash Gallery in New York. The artists in the exhibition runs the gamut from me, to Jean Dubuffet, to David Hammons, so I am looking forward to seeing what kind of dialogue is created with all of the different artists in the show.

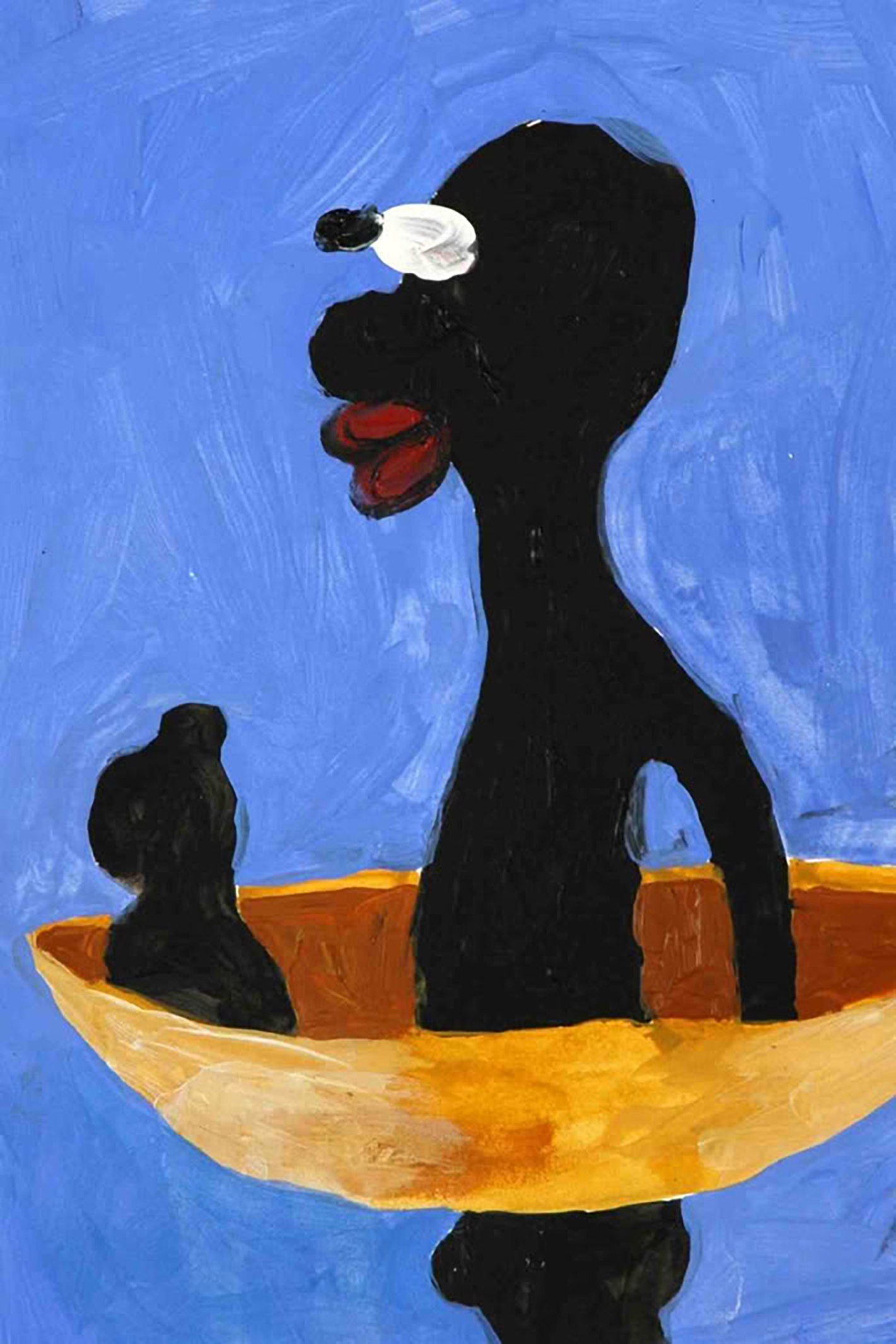

Nobody drops into the zing office out of the blue anymore. The late, great Dan Asher used to, but no one since. Except Jeffrey Hargrave. I first met Jeffrey when one day he randomly buzzed. Expecting the mailman or UPS, I must have looked disconcerted because as he walked up the stairs he announced he was just stopping by to pick up a couple copies of zing #21 (in which he has a project). Since then Jeffrey will stop by occasionally, when least expected, to grab some magazines. But isn’t that what a magazine office is supposed to be? People moving in and out, a center for thought, discussion, debate, and sharing? That’s beside the point. Jeffrey Hargrave is an African-American artist from Salisbury, North Carolina. Now based in New York, Hargave deals with representations of African-Americans, often putting them in the context of art history, remaking works by artists such as Matisse to include black figures, with stereotypical imagery. He currently has an exhibition, “Know Meaning,” up at The Phatory in the East Village.

Interview by Brandon Johnson

Hi Jeffrey. Good to see you earlier. We’re going to make this ZINGCHAT quick since your show closes on Saturday. The title of the show is Know Meaning and the work is pleasingly expressionistic yet deals in the imagery of racist stereotypes. What are you trying to say with these paintings?

That racism is alive and well, and although humorous, the paintings, drawings and video have an element of the macabre; which is interesting in itself because these Jim Crow-era images were used to degrade African-Americans, but there was a level of vaudeville comedy apparent in the illustrations.

Your first video piece is included. It’s of you singing a Lil Kim song. What song is this and what about it attracted you?

I love this rap because of its brazen use of sexuality and materialism. Kinda like a Warhol reinterpreted into a rap.

All of this work is concerned with representation—racist Jim Crow representations of African-Americans, Lil Kim representing herself as a powerful black female (which is then put in your context as a gay black male). Why is representation important to you?

That’s a very good question. Representation is very important to Lil Kim, African Americans, and myself as a gay black man. Society judges a person by what they represent and put out into the world. Lil Kim is a black woman talking about her sexual organs. She’s my hero. As a black gay man rapping the words of a black woman, I’m appealing to everyone: gay/straight, male/female. As a man having sex with another man, I’m both the husband and the wife. In all relationships gay/straight, male/female, one is dominate while the other submissive.

Your paintings are visually similar to examples of folk or naïve art. Is this a conscious choice or just your personal style?

Both. I am very inspired by naive and folk art. I also love children’s drawings and I’m influenced by them much the same way Debuffet and Twombly were. Drawing at its most simplistic and honest nature.

Paintings by your mentor, James Donaldson, are included in the show. How has he influenced your work?

He is constantly reminding me that the sky is the limit in regards to your life and artistic endeavors. He also showed me that nothing is impossible when it comes to art and following your heart.

Are there any other artists that have especially influenced you?

There are too many to name, but I will list a few: Gabriel Shuldiner, Noa Charuvi, Shirin Neshat, James Donaldson, Bruce Nauman, Robert Ryman, Cordy Ryman, Kiki Smith, Kara Walker, Bill Traylor, Cindy Sherman, Cy Twombly, and Walt Disney.

Interesting that you mention Walt Disney. At the gallery, you brought up the banned Disney cartoon, Little Black Sambo. What kind of influence did Disney have on you?

There weren’t too many characters of color in Disney movies and if there were they were usually singing songs with animated animals about how great life was or swinging from vines in the jungle. I was always glued to the TV whenever a Disney movie came on. My fav was The Sword in the Stone. The Disney charisma reached out to all. I have always been into the science of magic. Merlin was my own personal Houdini. But Walt was the greatest magician of all, and his magic was the ability to reach us all. That’s what I strive for in my own work.

What else are you interested in besides painting?

I love theater, modern dance, classical music, and hip-hop.

Cool! Thanks Jeffrey!

Untitled (Drum Rug), 2010, archival pigment print, 62 x 39 inches, installation view

Harrison Haynes is a North Carolina-based visual artist, drummer for Les Savy Fav, and contributor to zing #19. Raised in the rural outskirts of North Carolina Piedmont, he grew up among “DIY redneck-hippies: welders and carpenters that listened to ZZ Top and burned big vanilla scented candles in their outhouses” who “hosted demolition derbies, volleyball parties, big oyster roasts every fall, and homemade fireworks displays on the Fourth of July.” After spending time in Providence and New York, Haynes returned to North Carolina and cofounded with his wife, Chloe Seymore, the now-closed Branch Gallery in Durham, NC. He is currently enrolled in the Bard College MFA program.

Interview by Brandon Johnson

My entry point for your work is your watercolor series in zingmagazine #19. These have a very homey, Southern feel. Vignettes of Southern life—trucks, woods, beards, wood paneling. I really enjoyed the TV piece—it creates that quintessential TV light in a memory of warm brown furniture. Where are these scenes from?

The watercolors are based on my own snapshots. Mostly pictures I took up until about high school. I started using a camera at an early age, like 5 or 6. My dad gave me one of those 110mm little black rectangles. Later he gave me an SX-70 Polaroid Land Camera. It was primarily a social activity for me. I documented the schoolyard, trips I went on and had friends pose. I enjoyed the social aspect of taking pictures. The product, the prints and the sharing or subsequent display of those images, was secondary or even non-existent for me until much later. I wasn’t sure what to do with all the shiny pieces of paper once they got picked up from the pharmacy*. (*Isn’t the drug-store/amateur photography connection a funny anachronism?) While I was always interested in art, I never identified as a Photographer. I carried the photos around in cardboard boxes and looked at them from time to time. Later on in art school I studied painting. It never occurred to me to use the pictures as subject matter. I drew some imaginary line between the kind of photos I had been taking and what I regarded as ‘Art’. But I still had the boxes sitting around and continued to take pictures in the same way, now with a point and shoot 35mm. After finishing at RISD I was living back in North Carolina. I was sharing a house with my best friend since childhood, living next to the exact expanse of woods that we used to run around in as kids. He was working at the Center for Documentary Studies/Doubletake Magazine. Through him and the resource of the CDS, I got exposed to a whole new set of artists, people that hadn’t been on my radar at RISD; photographers like William Eggleston, Walker Evans, Mitch Epstein, Thomas Roma and William Christenberry. Naturally, I started to reassess the snapshot, the everyday, banality and the validity of those notions in art, the role they played in my own artistic sensibility. At the time I was working for a married couple that were comic book artists. They had hired me as an assistant colorist. Their process back then (another anachronism) was to fill-in xeroxed copies of the inked pages using watercolor. Then a digital colorist would translate those mockups for print. I had to adapt to a very utilitarian technique with the watercolor and in that way I became quite good at it. I discovered the more nuanced procedures through mistakes. The subtlety that’s achievable with watercolor lends itself nicely to transitions of light and shadow, gradual chromatic shifts, a certain evenness of surface. Those were the characteristics that lead me to view it as an appropriate medium for translating the snapshots. There was also a connection in the substrate: paper to paper. The thing started as pretty simple way to carry the photographic images into another state, to see what they meant, to me, to others, having gone through that shift. I selected a dozen or so photos based on impulses not quite articulated at the time. In retrospect I think I gravitated toward pictures that had a certain openness where familiarity could be a point of departure into something more ambiguous. In executing the watercolors I set out to reproduce the images to the best of my ability. But there’s a push and pull between reproduction and materiality, the border between photo-realism and more direct applications. Like that blob of moisture on the edge of TV screen in the piece you referenced above. I might have said, ‘Ah Fuck!’ when my overloaded brush hit the paper there. But that blur contributes to autonomy in the piece. The Southernness wasn’t really something that I considered until I had moved to NYC. I realized that I was making something about where I was from, about North Carolina, about the post-hippie scene I had grown up in there. Perhaps the 500 miles allowed a productive kind of cerebral distance. I started thinking about my childhood and the kind of places and people I was around and again I was struck by this idea that there was a good amount of compelling subject matter sitting right under my nose. I wrote a short blurb for the bio section of that zingmagazine which indicates some of those ideas.

Lately it seems like you’re focusing more on collage and photography. In the Disruptive Patterns series you retain some of the Southern subject matter mentioned above, but frame them as clusters of photographed objects or in uncanny, borderline surrealistic, juxtaposition. Was there a point of transition from painting to this type of work, or have you always worked in multiple mediums?

The transition was the impulse to deal with those same photographs head-on. I had been skirting around the actual photos, working FROM them in a variety of ways. It felt like it was time to physically address them. The first time I cut into one of the prints there was a great relinquishment of preciousness. I just started hacking them all up with scissors, hundreds of photos, culling individual objects and areas from within each photo for later use. I made big piles of the bits and then sorted them according to size, theme, color, light source, etc. I have permanent callouses on my knuckles from all the scissor-use. It wasn’t an abandonment of painting, but it was the beginning of an acknowledgment that I can work in multiple mediums at the same time. I think this move also paralleled an impulse to eschew overtly personal subject matter, to move towards a more open or fragmented narrative. Also at this time, I started more actively engaging in photography as a tool for the gleaning of images that would later appear in the collages. I’m also a drummer in a band that travels a lot. For about 5 years I took a Canon Demi 35mm half-frame camera with me on countless tours and shot landscapes, found objects, highways, people, cars, incidental things, peripheral things. I so wasn’t interested in documenting the rock ‘n roll part of it.

In other series, you introduce more layers, complicating the idea of photography and collage further. One of my favorites is Featuring, where you create these text-based, geometric objects using a section of printed material and a mirrored corner, forming 3D situations from 2D objects. Where did the idea for this series come from?

In 2009 I was accepted into the Bard College MFA program and I set out to tackle photography more deliberately. Featuring is a series I did in between my first and second year at Bard (I’ll finish up at Bard next summer, 2012). They’re at the intersection of a few things going on in my head at the time. I was thinking about collage, but looking for ways to execute it sculpturally, or as a still life, and then to make a photograph of that so that the photo would be the final work. I saw the Czech Photographic Avant-Garde exhibition at the Phillips Collection in DC that year and it really floored me. I got excited by the idea that a photo could be a document of another work, even something ephemeral, so that the photo becomes the thing, becomes autonomous. I’m getting another dose of this notion today (almost 80 years after the fact. Ha!) reading Walter Benjamin’s ‘Little History of Photography’. He’s describing the academy’s initial reluctance to accept photography as art at the exact same time that photography was beginning to supplant art-viewership through the universal acceptance of graphic reproduction: art-as-photography vs. photography-as-art. Anyway, at the time of this work, I was looking at a lot of records, LPs. Along with 6 other artists, I had been asked to curate a crate of 20 albums for the exhibition, ‘The Record: Contemporary Art and Vinyl’. I was digging through my own collection and spending lots of time online looking for specific albums whose cover art used mirror images, refraction or reflections. I had also used mirrors as still-life elements in an earlier series of photographs. The source material here are those little promotional emblems you’d see on album covers in the 60’s and 70’s indicating the hit songs included on that LP or some other message of advertisement. I photographed them and then manipulated the images by placing those photos at the intersection of two mirrors creating a cyclical pattern.

In your series Practice Space, you’re incorporating another major part of your creative output—music and its ephemera. Prints of these ephemera—rugs, cymbals, foam—are remade as trompe-l’oeil objects. This exposes a sculptural side of photography—prints acting as an installation of relics. Can you explain how you arrived here?

Practice Space deals with the objects that are found in a band’s rehearsal space. I started delving into the arbitrarily rigid dichotomy between music and art in my life, how divergently I regarded the two practices despite their obvious overlap and mutual influence. I had been in bands as long as I had been making visual art but I wore the hats separately, and seldom identified with one pursuit while in the midst of another. At Bard I was immersed in an interdisciplinary environment and so I began to think about ways to remove the divide. The cymbal occurred to me as an object that I had a very functional but in-depth relationship with. Taking a picture of it and then cutting it out removed it from its everyday context and I suddenly saw it in a very formal way and that was really exciting. Other objects followed: the rug that lies under the drum set, the convoluted foam that gets stapled to the wall to deaden sound. There’s an additional play with materiality and even sculpture in the cockeyed analog between the new cut out photo and its parent. The new ‘rug’, a 40″ x 50″ archival inkjet print, flopped around just as unwieldily as an actual carpet. For a long while, without a good place to store it, it was slumped over a chair in my studio and was regarded by visitors as an actual rug pending further scrutiny. Tromp-l’oeil was not my first intention although it was an inarguable result. I was more interested in an object that passed through many states of being and had returned as a cockeyed version of itself.

You are in an upcoming exhibition at Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts called Here based on the role of “place” in art that contests the idea of regionalism. What will you be showing? And in a broader sense, how does North Carolina influence your work?

For the PAFA show I’ll be focusing on a performance work called LRLL RLRR that I started doing in 2008 in which another drummer and I play the same drum beat in unison for 74 minutes. I’m also producing a two-channel video based on the performance which will exhibited for the first time. The performance grew out of the same impulse that lead to Practice Space, drawing on my experience as a musician as subject matter for visual art. But here it’s more direct. Each time I’ve staged the piece it’s in cooperation with another drummer, someone from whichever city we’re in. So for the PAFA show my collaborator will be a Philadelphian. The collaborative aspect is indicative of the communities that I’ve come to be a part of through touring. During the mid 1980’s, when I was first discovering underground music culture, regionalism was intrinsic. Every city had a scene and group of bands that sprung out of that. On show flyers, each band’s name was followed by a parenthetical indication of where they were from. Certain areas had certain sounds, aesthetics. By the time I was playing in a band and touring nationally, regionalism and categorization had begun to dissipate. Bands were bound less by aural similarity and more by an overall DIY methodology. Now of course it’s all upside-down.

What are you working on now? Anything to look forward to?

Right now I am really focusing on expanding the LRLL RLRR project for the PAFA show. I shot the video footage last week and now will begin the editing process. It’s a new medium for me. The considerations and procedures are related to photography but the chronology of the process is so different. I’m used to photographing inanimate objects and this was dealing with moving, human subjects, so there were all sorts of new imperatives. Time becomes crucial since you can’t expect people to sit in under the lights forever and ever. Plus I was dealing with sound recording, mic placement, etc. It’s all very energizing, actually.

Also, as an object accompaniment to the video, and to future performances of LRLL RLRR, I’m publishing the musical score: over 2000 measures of the same drum beat written out as notation along with a mirrored accompaniment to indicate the two drum sets. It’s a ridiculous kind of ‘drawing’ of the performance that people can take home with them.

Something to look forward to is this: my band, Les Savy Fav, along with the bands Battles and Caribou, are curating an entire weekend of programming at the All Tomorrow’s Parties festival in the UK in December. Each Band gets a full day/night to stock with music, DJs, films, whatever. It’s a pretty huge honor, to the point where we’ve sort of done like a Dungeons & Dragons-type fantasy game about in the past. But the selection process ended up being a lot harder than we thought. Not everyone we wanted was available, or alive. And we had some unexpected obstructions of consensus (turns out not all of us were into getting Kris Kross back together). One thing we were pretty quick to agree on was a desire to get Archers of Loaf to play. They had started playing shows again recently and so it ended up being possible. I’ve been delving back into all their LPs lately and I’m still entranced by their singular mannerism: odd chords, odd structures, odd lyrics that somehow coalesce to form rock music that is often very relatable. I saw them play last week here in NC and they were harnessing the same unselfconscious, ecstatic energy that the songs were first born out of. And they played the most obscure songs with as much fervor as the sing-alongs. Although with the show taking place in the bull’s eye of their first wave, every song was a sing-along, a somewhat distracting thing if you happened to be standing next to someone with a loud, bad singing voice.

Anyway, here’s the link that tells about ATP: http://www.atpfestival.com/events/nightmare2011/lineup.php

Other than that the future is revolving, counterclockwise, hurricane-like, around my last year at Bard MFA, next summer. I’ll be concentrating on my thesis, the actual work and the written part, over the next 9 months. LRLL RLRR along with other work happening now, and some nascent ideas, will funnel into the project, probably get puréed a few times, then congealed, sliced and served up. I have a show at UNC-Greensboro in January where I’ll be able to look at how some of these things can relate in one space.

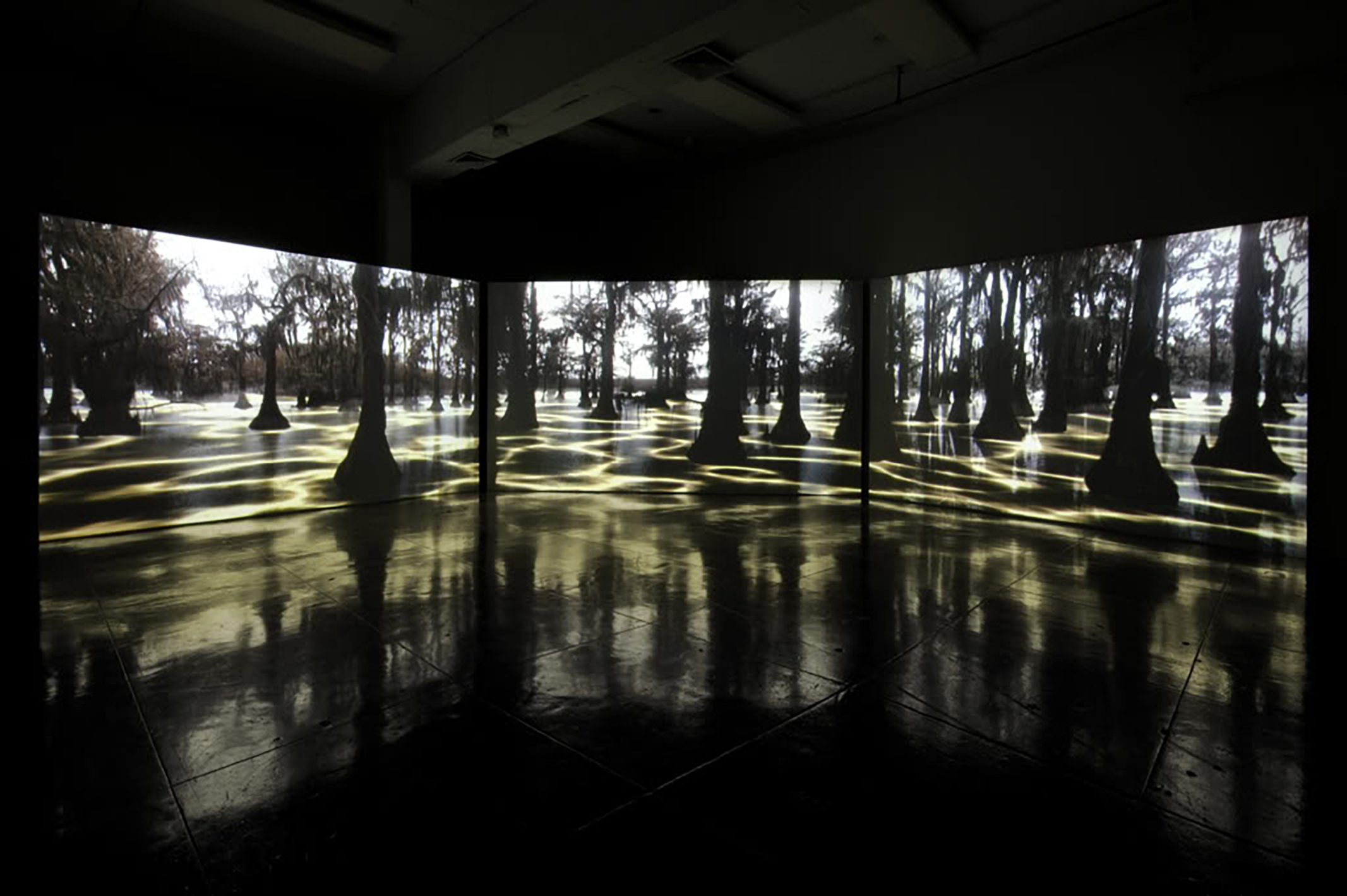

LEVIATHAN, 2011, three-channel high definition video, 20 minute loop.

Originally commissioned by Artpace, San Antonio

In the aftermath of a week with both a hurricane and an earthquake on the East Coast of US, and year in which, Japan has been devastated by an earthquake, a tsunami, and its Nuclear aftermath, and with a year of the most devastating oil spill in history, Kelly Richardson’s work has the relevancy and chilly methodology to wreak havoc on the otherwise still perceptions of her subject matter. She embraces a 19th century axiom—“The Apocalyptic Sublime”, with the precision that George Lucas first explored in his THX 1138 or the clever tautology of Ridley Scott’s Blade Runner. Her work captures fear, anxiety, resolution, beauty, mystery, omnipotence, awe, and desolation people feel in the presence of the unknown both in nature and in life. I had the pleasure of sharing a residency with Kelly Richardson at Artpace in San Antonio, curated by Heather Pesanti, and was initiated into the weird and luxurious sensation her video installations evoke. And now I have begun to look at the world through some different viewfinders, and like with all good art, wine, hallucinogens, or sex—after experiencing it—the world seems a little different, a little more fragile, and yet, a little more epic. What follows is our emailed Q&A, or “Come on Irene [sic]”.

Interview by Devon Dikeou

Terra Nullius, landscape work not touched by humans would seem to have a strange relationship to you and your work. You live in the UK—the ultimate non Terra Nullius landscape—it has been centuries being sullied, sculpted, terrorized, or tamed. And yet you try to find landscapes that might have any or all of these qualities in both hidden and obvious ways, and then you digitally create some effect—in effect a super Terra Nullius. Can you speak about this . . .

I’d say it’s increasingly true that the work focuses more and more on locations without signs of human interference. Occasionally, there are works which use manmade structures of some kind, but many of the ideas dictate using the Terra Nullius landscape. Most often, unplanned indicators of civilization inform the work in ways which don’t support what I’m after. If elements of sullied landscapes are present in anything I make, it’s deliberate; either it has been inserted digitally or selectively left in the shot to support the idea.

While majestic and beautiful, the work should also have an eerie, if not terrifying quality. If they function properly, the viewers feel consumed by the landscape, losing themselves in the work. If there are signs of a tamed landscape, the threat of the un-urbanised wild isn’t present which prevents fear of the potentially unknown.

Let’s talk about what Woody Allen calls, “Your early funny work”, and your early work is really funny, literally. Like the “Ferman Drive,” or “The Sequel,” much less the “Wagons Roll” . . . Humor, what are the advantages and disadvantages . . .

I used humor in the past as a way of inviting people into the work. From there I was hoping they would unpack it and end up feeling all sorts of other, often conflicting sensations. At some point though, I guess it was 2006, I decided that humor was far too specific. I’ve always tried to make ambiguous works where the viewer is unsure how to feel about it; it may be beautiful but at the same time unnerving (as above) and while humor is a great entry point, it ran of the risk of overshadowing what I was really after, the conflation of numerous ideas and interests which inspire a kind of contemporary sublime.

The Erudition, 2010, three-channel high definition video, 20 minute loop

This movement that you introduced me to, the “Apocalyptic Sublime,” pretty much sums up Edmund Burke’s idea of the sublime, “fearful joy.” But it really has some fascinating history and amazing relation to your work. Will you say something in relation to this.

The manifestation of apocalyptic art and its popularity came about during a period of domestic unrest, foreign wars and quite significantly–as it pertains to its relation to my work–anxieties towards major societal and environmental upheaval caused by the birth of the Industrial Revolution, which came to fruition around the same time. During the 18th century, interest in the Apocalyptic Sublime was expressed through what would have been ‘popular culture’ for the time: writing, poetry and art. Similarly, with widespread predictions of impending environmental meltdown as a direct result of the Industrial Revolution, during the last decade we’ve witnessed a return to imagery and stories depicting the Apocalypse with the film industry producing an unprecedented 50+ films illustrating various apocalyptic themes, many of which contain scenes which use similar techniques used by the painters in the 18th century to inspire the sublime.

Artists who were associated with the Apocalyptic Sublime envisioned catastrophic outcomes of this era, looking forward to what may be a result of the Industrial Revolution. We’re now sitting on the other side, facing its effect on the planet and ourselves. By way of the film industry, the Apocalyptic Sublime, or at least the popularity for consuming imagery depicting a catastrophe-ravaged planet has returned, almost certainly reflecting a like, collective anxiety towards a very uncertain future. My work plays into this, along with a number of other ideas and influences.

Ok the Creature From the Black Lagoon . . . it looooms in “Leviathan.” What is your worst nightmare?

I’ll share two actual nightmares that I’ve had which were equally terrifying. The first depicted the end of the world by way of an electrical storm. I was on a space station of some description, with the perfect vantage point to witness our planet being zapped with a wild web of blue electrical currents. The second, along a similar vein, involved the sun which ‘didn’t rise’. It was surprisingly peaceful and calm for a world which understood that it had hours left to live.

The Group of Seven. This is a hugely influential Canadian art group from the 1920s created what I imagine is a pretty hard body of work to deal with for a Contemporary Canadian artist working in what is seemingly the “landscape” genre. But you reference them quite naturally, or as a juxtaposition, unnaturally. Give us a clue into your thoughts on this . . .

As a Canadian artist it’s impossible to make work using landscapes without being part of that history. One of the interesting objectives of the Group of Seven was to showcase the beauty of the rugged, untamed Canadian landscape. I feel like I’m approaching things from the other side, after landscape–where I’m fabricating the wild, in a sense, to create a sensation of the sublime, which from my perspective has largely disappeared from the natural world. While I’m representing beautiful vistas like the Group of Seven, I’m also incorporating ideas about our experience and understanding of our highly mediated world where fact and fiction are barely decipherable and how we can no longer view landscape without being aware of how much we’ve drastically altered it, both physically and digitally.

Exiles of the Shattered Star, 2006, single channel high definition video, 30 minute loop

As a youngster from Colorado, of course I was privy to some of the most absolutely exquisite views in nature. In fact, one of those views, that of the Maroon Bells is perhaps one of the most downloaded screen savers in the world. So in fact, most people’s view of the famed mountain landscape is not a natural experience of the mountains, but a virtual one, that appears onscreen when activity on a computer has ceased. And according to Baudrillard “Simulacra” in a way means that the virtual experience at least equals, maybe excels, and perhaps exceeds the actual human experience. Do you think of your work as a critique of this or do you embrace it as a way of creating landscape terroristically, with our only tool left, digital manipulation?

I embrace digital manipulation as a tool to allude to the multiple, hybridized and seemingly un-navigable “realities” we now exist in. It’s not so much of a critique as it is acceptance. This is the world we live in; now what?

Which brings me to my last question. Often times when you make a piece, there is some type of Pilgrimage involved, like the Pilgrimage described in Michael Kimmelman’s Accidental Masterpiece chapter, “The Art of the Pilgrimage” in which the meaning of the Pilgrimage from Colmar to Marfa is elucidated upon. For you, traveling to places like Uncertain, Texas is just the beginning. You share the Pilgrimage with the viewer—a generous move as opposed artists whose work a viewer must/need to physically travel to, to see/view—like Smithson’s “Spiral Jetty,” Di Maria’s “Lighting Field,” or Judd’s “100 Aluminum Boxes.” How do you feel about bringing the Pilgrimage to the viewer as opposed to requiring the viewers’ dedication of time and effort in order to see the artwork/landscape in actuality . . .

That’s an interesting question. Most of the time I seem to be messing with pristine views which physically, I would never want to mess with. Working digitally also means that I can create impossible or improbable scenarios. I couldn’t transform the Lake District in England with raining meteorites, I don’t have the means of installing a vast field of holographic trees and with the most recent piece commissioned by Artpace, Leviathan, the phosphorescent life form in the water doesn’t exist.

Also, by removing location and all of the information associated with it which grounds perspective and understanding means that I can bring viewers into unfamiliar territory. I can transport people to another time, into possible futures or the distant past. In contrast to these strange, alternate spaces, I can ultimately make visible our current environment with some measure of hindsight.

Kelly Richardson’s work is currently on view in ‘The Cinema Effect: Illusion, Reality and the Moving Image’, Part 1: Dreams at Caixaforum, Barcelona, curated and organised by the Hirshhorn Museum and Sculpture Garden (through September 4, 2011) and ‘Videosphere: A New Generation’ at the Albright-Knox Art Gallery (through October 9, 2011). Please visit her website at www.kellyrichardson.net for further information on her work and upcoming exhibitions.

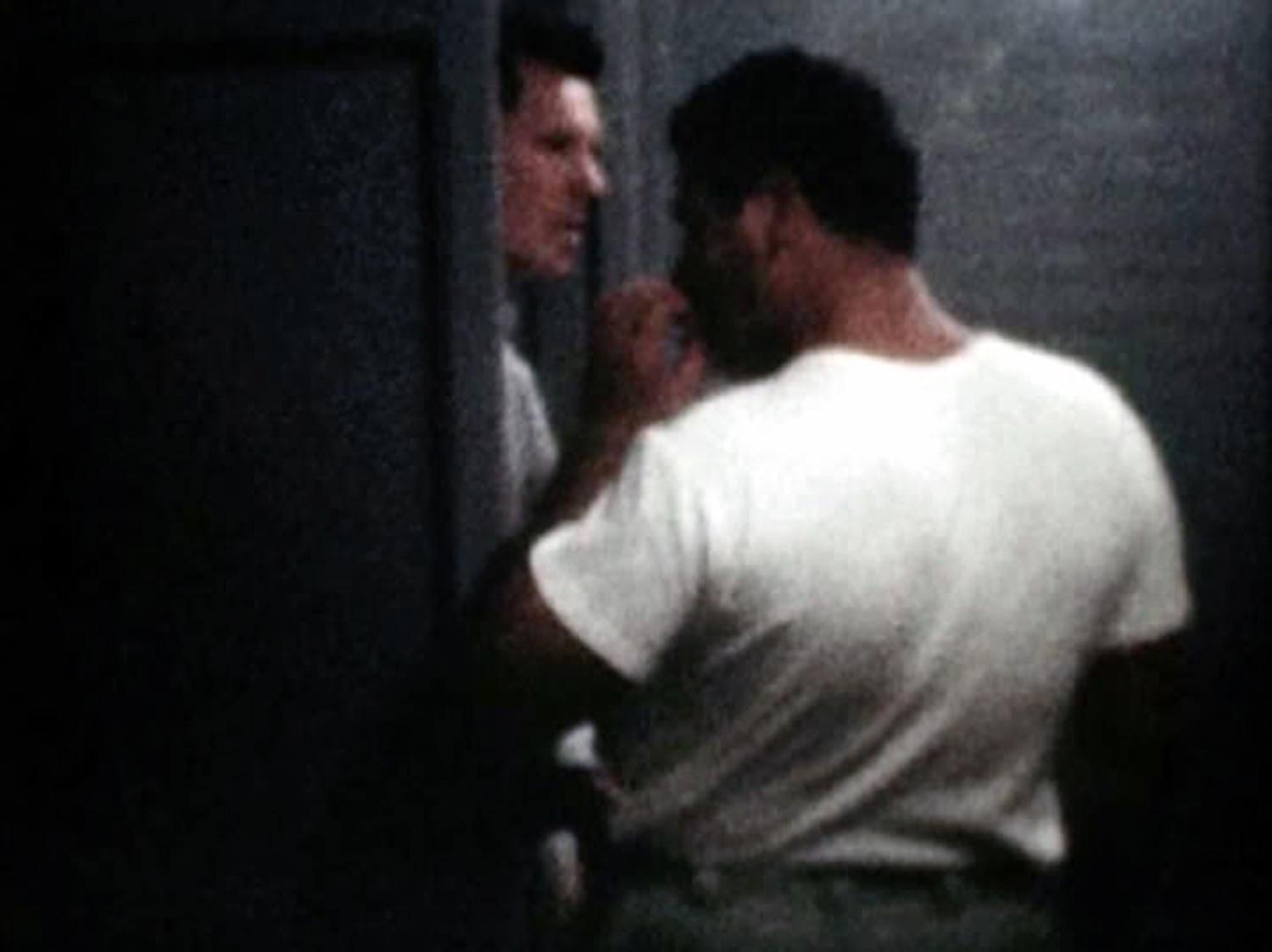

Still from Tearoom, 16 mm film transferred to video, color, silent, 56 minutes, 1962/2007

William E Jones was born and raised in Ohio, but is now one of LA’s leading independent filmmakers. I recently caught up with him about his highly emotive body of work, which predominantly deals with the deconstruction of artifice and façade in found footage; this has included gay pornography from post-Soviet states (The Fall of Communism as Seen in Gay Pornography), homophobic police training footage (Tearoom), and Cold War propaganda (Berlin Flash Frames). He recently exhibited in The Sculpture Center in Queens, and his work has otherwise been shown at museums and film festivals worldwide—including the Musée de Louvre, MoMA, the International Film Festival Rotterdam, Sundance Film Festival, and was the subject of a retrospective at Tate Modern.

Interview by Ashitha Nagesh

Just to begin, I’d like to say that I really love your work; it’s striking, without being explicit. Could you tell us a bit about your influences? What is your particular attraction to old war footage and gay pornography, two things that wouldn’t necessarily usually go together?

In the present era, war and pornography have more in common than may at first appear to be the case. US military personnel in the current theaters of war spend enormous amounts of time in isolated places where fraternization is very unlikely. Watching porn is a major pastime, and as the notorious photographs from Abu Ghraib revealed, there is some production of porn going on, too.

Since 1973, the US armed forces have not resorted to conscription, which, while scary for individual men during the Vietnam War, had the virtue of bringing together a range of classes in one social unit. Now the military is perceived as a vehicle of upward mobility for working class people, a perception that often proves to be illusory, or at best, immensely risky. This bitter reality seems to trouble those governing the United States (or at least their most hawkish elements) very little. They behave as though American working people are expendable, though perhaps not as expendable as the foreigners they are sent to bomb.

I suppose there was a time when pornography offered the promise of becoming a star, which is its own peculiar type of upward mobility. With the recent rise of bareback and amateur porn, and the virtual collapse of profitability of the adult video industry, pornography has become the realm of disposable people. Their bodies entertain us fleetingly; their fates generally do not concern us.

The act of repetition simultaneously fetishises and desensitizes the material for the viewer, and this can be seen in Film Montages (for Peter Roehr), and in Industry. What drew you to repetition? Do you feel that the act of repetition makes the non-explicit footage somehow explicit, in the Freudian sense of uncanny?

Strict repetition is a strategy almost alien to the cinema. It is absolutely fundamental to music (without it, there would be no rhythm) and rather common in modern art (as in Warhol, minimalism), yet seeing exactly the same thing over and over would never happen in a narrative film, which, we must acknowledge, is the dominant form of cinema. Peter Roehr appeals to me because he took up repetition with complete consistency, and applied it to his movies without moderating it or “cheating.” This bracing disregard for the rules of how to make a movie, at the risk of engaging in a kind of sadism, suggests one of the ways that film and art are still distinct as media. Filmmakers care that their works are watchable, because if spectators don’t stay in the theater for their movies, they won’t get to make any more of them. Artists tend to take a position of indifference on this question. Few have seen Empire in its entirety, but this hasn’t harmed Warhol’s status as an artist; it may actually have enhanced it.

This idea is especially poignant in your work The Fall of Communism as Seen in Gay Pornography—given that it seems to be about something far more personal than new capitalism and the commodification of sex. In fact, what I took from The Fall… was that it was particularly haunting, not only because of its recent cultural relevance, but because it evokes that feeling of strangeness, of finding one’s way in a completely new environment, navigating the unknown and being taken advantage of—which I think are feelings that most people can, at least partially, relate to. So, I found it interesting how this work was so personal, whilst also speaking of a wider political context. What was your thought process whilst working on this film?

From my own personal point of view, one poignant aspect of The Fall of Communism as Seen in Gay Pornography was that I had no money when I made it. I consider the collapse of state socialism in Eastern Europe the most important political event of our lifetimes. At the time it happened, I was living thousands of miles away and was not capable of recording anything directly. Yet the transformation of the way people lived was so profound that evidence was everywhere (as it still is, I would argue). It was just a matter of me finding this evidence and placing it in the proper context. Fortunately, I had the presence of mind to realize that I needed to look no further than the neighborhood video store.

Despite the efforts of a century of narrative cinema to make us believe otherwise, individuals rarely make history. We generally experience historical change as dislocation and confusion. This is the pathos of modernity: no matter how smart or secure we feel ourselves to be, our consciousness has trouble reckoning with new forms of domination and the latest crimes committed by managers of capital. At certain moments, the rules of the game are laid bare. I think The Fall of Communism as Seen in Gay Pornography contains a few of them.

In your recent work, Eyelines, you present found film footage of advertisements from the 60s and 70s and compile them, in order to distort and confuse the original intention of the images. The footage has naturally faded to various shades of red, and your contribution to this is mostly in the act of compilation. Similarly, when discussing Tearoom you have said that you ‘didn’t want to obscure the actions of the police by imposing your own decisions on the material’; how do you explain this move towards less-appropriated and more found footage?

Eyelines dismantles one of the fundamental figures of narrative filmmaking (a holdover from figurative painting), the eyeline, by looping very brief shots and alternating them in intervals so quick that the effect is stroboscopic. The work is reminiscent of the “structural” avant-garde films that analyzed the formal aspects of cinema, often at a microscopic level. Eyelines also has a mathematical, or perhaps musical, structure, as many of my works do, though this is rarely obvious. Every single permutation, that is to say every combination of individual frames, is exhausted over the course of Eyelines’ 1 hour and 51 minute length. Though the frames are not altered at all, I wouldn’t exactly call Eyelines a “found footage film.” For one thing, the total length of the source material is only approximately 30 seconds. The visual effects are achieved through montage, and as the piece plays out, the multitude of combinations invite spectators’ eyes to play tricks on them.

I had the pleasure of seeing Berlin Flash Frames at The Sculpture Center’s (NYC) recent exhibition ‘Time Again’. At the beginning of the film, the images are fast and obscure, before eventually slowing down to show more clearly the collapse of the actors’ and civilians’ assumed ‘camera face’ identities. What interests you about this? Why did you choose a slow revelation over an immediate one?

Immediate revelations are better suited to billboards and abstract paintings than to moving image works, which must unfold in time and have the possibility of justifying their duration.

There’s also a theme of disguise and acting, and the undoing of this, in your works that is prominent in The Fall…, Berlin Flash Frames, and even Tearoom. You seem to be fascinated by this idea of letting one’s guard down, captured in accidental footage of people caught in deeply intimate, unstaged and personal moments—it was therefore fitting to see you refer to Tearoom as ‘an historical artifact.’ So, in light of this and of your work with old wartime footage, such as with Berlin Flash Frames and War Planes, is the preservation and, perhaps, redefinition of history important to you? How do you view the relationship between documentary and propaganda—what in particular draws you to working with, and the deconstructing of, docustyle propaganda film footage, such as Berlin Flash Frames or Tearoom?

Propaganda films exploit the rhetoric of traditional documentary forms in order to commit a fraud. Documentary is not a style, but an ethical position the person representing takes toward the represented. In propaganda, ethics are of little concern.

The original material of Berlin Flash Frames interests me because it exhibits a diversity of approaches to filmmaking. Outright falsification employing actors on sets exists side by side with surveillance footage of the construction of the Berlin Wall, and there are other sequences that appear to be documentary footage, though they are not exactly that. An actor from the fictional scenes circulates among crowds of people waiting in line at government offices in West Berlin. Most of them were aware that they were being filmed, but there wasn’t much they could do about it, besides looking away (which preserved their anonymity) or looking directly into the camera (which ruined the take). I can extrapolate from this footage that every resident of West Berlin was a (willing or unwilling) extra in one giant Cold War movie.

Tearoom presents a different range of contradictions. The police force of Mansfield, Ohio (and the vigilantes that supported them) deemed it necessary to record surveillance footage of men having sex in the center of their city. The film was not shot automatically by a machine alone. A police officer had to stand for hours in a closet behind a two-way mirror watching men go in and out of a public toilet. He chose what to shoot: he turned the camera on and off, and within certain physical restrictions, he moved the camera. What was intended as an “objective” document of deviant sexual activity has come to seem transparently subjective. When an attractive young man enters the space, the camera moves frenetically, as though it cannot get enough of him. In the early 1960s, public opinion held the men in the film to be perverts and those who commissioned, shot, and used the film as evidence in court to be fine, upstanding citizens. Today, spectators are likely to form another opinion. Tearoom allows an audience to reflect upon this historical transformation.