Through the patch-work of voices rasping from the most notorious era of American history, Laird Hunt’ s most recent novel, Kind One (Coffee House Press, 2012), depicts the ordinary, excruciating lives of three women in antebellum America. Though minimalist in approach compared to previous works by Hunt, Kind One operates via a series of trompe l’oeils, that is, if you are lulled by the steady round sung by Ginny, Zinnia, and Cleome as they embrace and beat, soothe and scar one another, you may not notice that slowly, slowly you have been saturated with countless other stories—an infant who drowned, a secret walk in the woods, a purple string extended between a shack and a well like an artery, an uncomfortable afternoon with one’s own stunned ruminations about the humiliation of American history. The exploration of power struggles fought at close range is the engine of the text, and characters no sooner become pliable and plain, a cozy surrogate from which a reader might comfortably take a seat, before they implicate themselves in a more difficult, bruising human dance of cruelty and friendship.

Interview by Rachel Cole Dalamangas

Of all your work I’ve read, Kind One operates the mostly closely to realism, although I would argue that if realism is the convincing illusion of reality, Kind One is the convincing creation of a work of realism. The intentional materiality of narrative and language both induces a dream and calls attention to the work as a creative act. Like other novels of yours, Kind One calls into question the nature—and reliability—of reality as a phenomenon itself. Can you tell me about this choice to write a novel that appears to be more realistic than your past works? Were there particular writers that influenced this choice?

I’ve been listening to Roscoe Holcomb sing today, in fact he is singing in my headphones as I type. I was trying to imagine parsing whether what he was doing was a kind of realism— in fact I can barely understand what he is singing most of the time and who knows what the sound of a banjo, his banjo means (both aspects of what he does certainly, of course, signify). It is certainly real. It’s coming through my headphones. But it seems to me real in much the way the coffee in my mug is real and not at all in the way a novel written in the realist manner is typically experienced as representing/counterfeiting the real. I’ve always aspired to something like Holcomb rather than something like Dickens, if that makes sense. This isn’t to say that some of my work doesn’t make use of realist devices and approaches. Kind One certainly does. But I like to think I will have lost whatever more or less serious game it is I’m playing if I ever begin, in a fundamental way, to imagine I’m working towards or away from a set of group think conventions (and group think happens across the aesthetic spectrum). In this context I could cite as influential work as diverse as Gourevitch’s We Wish to Inform You That Tomorrow We Will Be Killed with Our Families and Akhmatova’s Testimony and Yourcenar’s Memoirs of Hadrian.

Violence isn’t censored much in Kind One and that narrators are indeed quite frank in their recount of events. The use of language, however, tends to avoid clinical descriptions. Ginny says her husband “comes in at her morning and evening” to describe six years of a routine of incidents that includes both consensual sex and marital rape. Alcofibras is “fitted for drapes” when he is whipped to death. Rather than concealing the violence, I thought this understated diction was frustratingly distant and therefore powerful as a mode of description for the content. Why did you choose to depict violence primarily in these voices as opposed to an authorial voice?

It’s certainly the case today that you can sit on the bus or in a restaurant or almost anywhere you can conceive of and listen to someone speak in outrageous detail into a cellphone about the injuries suffered by someone’s cousin in a car accident or a fight over a parking spot or about the colonoscopy that someone has undergone as a result of the natural deleterious processes of aging, and that a whole array of television programs and movies exist seemingly with the single goal of laying out with great precision the results of trauma on the human body, actual or imagined. All of this is aided and abetted by the internet, which can serve up the specifics of horror suffered by those who cohabit our planet at the touch of a link. I’m not sure though that any of us speak to ourselves in this way, not to our deeper selves, not to the parts of us that are really listening to what we have to say. What is the shorthand of the soul? Kind One proposes itself as a kind of whispering, the voices pitched between speech and writing. A whisper can chill. A quiet remark can annihilate. And sometimes it is all that can be managed. All that we are up for saying. Frederick Douglass speaks of the “blood-stained gateway” that led into the institution of slavery. He meant the whip. He is far from being afraid of specifics but he also makes use of this kind of chilling, potent, experience-based metaphor. In Kind One, Zinnia “tells” Prosper what was done to her by Ginny by holding his hand up to her scar. Sometimes all we can do is point.

One way that Kind One produces an illusion of realism without actually utilizing the traditional techniques of realism to the letter is via a relapse of imagery—the baths, the key, the purple string, the well, the silent coupe, the daisies, the pigs. It’s rather songlike in that way and there’s a definite nod to poetry at work here and the patterning of motif is elaborate. Bizarrely, this is also the mechanism of propulsion taking precedence (I suspect) over plot. What is your process for conjuring a narrative with direction and energy?

One of the particular challenges of first person narration is that plotting finds itself doubled. First the person speaking needs to decide how he/she is going to tell the story, how it is going to be arranged, plotted, then the writer needs to do this. One could argue that this is of course all part of the same authorial gesture, but in the case of Kind One, which has multiple first-person narrators, I found it very much worked this way. Ginny needed to decide what she was going to say and see what she could say, as did Zinnia and the others, and when they had all finished I needed to go in and rearrange the narrative furniture, paying close attention to what was distinct in what they had to say and what overlapped. Patterning—and you’re right that there is a fairly complex system of reprise and echo at work throughout the book—is much more interesting to my mind than putting into play some sort of received mechanism used to create the illusion of a causal universe. The patterning has to be complex and unpredictable, or verge on the unpredictable, and it may well be the variety of pattern that is only fully apprehended afterward even if it is felt throughout. I think there is great propulsion to be gained by working with both blatant repetition (pigs, pigs, pigs!) and a subtler, much subtler system of reprise (kind, nice, gentle, demon, fury).

When Barthes calls literature a tissue of quotations he is also calling it a tissue of repetition and reprise. We don’t need Barthes to tune into the dominant that reprise represents in life on and off the page. All you have to do is live among others to hear yourself and them say the same or practically the same thing about some reasonably small number of things over and over and that is life. Far from finding this numbing, I hear (and see: our gestures repeat and reprise themselves too after all) great energy and power accruing in this mechanism of resaying that plays itself out over the course of our lives. Spells and chants and words of power are powerful exactly because they insist, they say again, they confirm: which we all do all the time without necessarily thinking of it in this way. In this context, withholding, delay, echo and return are powerful tools for exploring the potential as well as kinetic energy of a work and the language that manifests that work. To organize the constituent elements of books (which is another way of saying to “plot” them) with this in mind strikes me as completely reasonable.

The features of the inner human life that are examined most frequently in your work are madness and memory. Another crucial quality to the relapse of imagery—and I suspect, the propulsive energy it invokes and rides—is the exploration of the process of recollection. How does narrative relate to memory?

It is overlapping to the point of being identical. Still, there is that gap, that small difference between narrative and memory, that keeps them distinct. I remain powerfully drawn to the exploration of that gap. It feels to me like a planet or planetoid object that (like Pluto) that for so long was sensed but not seen.

Like prior novels, Kind One is written in a series of fragments. A narrative arc is intact (or rather mostly, but broken in choice ways to create space for haunting absences) and the plot deals with time as linear. On the one hand, I’ve always read your use of the fragment as a form of subtle play with the fragmented nature of memory. On the other hand, I often wonder if writers who work in the fragment are responding intuitively or intentionally to the impact of technology on attention span. William S. Burroughs correctly predicted that the television would supersede the book as the most popular form of narrative art and new technology has irrevocably changed the publishing industry in the last five years alone. What is the future of written narrative, in your opinion? Do you think that the use of the fragment is a way to appeal to the preferred (and trained) modes of modern consciousness without losing artistic sophistication?

I’ve been very interested in and heartened by the explosion in very recent years of book arts, in some cases as a very conscious rebuttal to the shifts being enacted in the world of books by the cigarette-like spread of technology that shows all the signs of being produced not to empower but to ensnare. New Directions is among the higher profile places that have moved aggressively and with great success to celebrate the technology of the printed book. I’m thinking of work like Nox by Anne Carson or the Untouchables by B.S. Johnson, but also the lovely edition of Microscripts by Robert Walser and the very handsome, magenta-stamped edition of essays by Roberto Bolaño. The graphic novelist Chris Ware just published his own book in a box, which is essentially a collection of gorgeous fragments. He wanted to make and disseminate something that could not be reproduced digitally (his drawings often feature parents spacing out with iPads in their hands as children play nearby).

There are also projects like the magazine Birkensnake, co-edited by Brown and Denver graduate Joanna Ruocco, that exist to move from eye to hand to hand to eye and could never be experienced in all their wild papers and materials and unusual inks with an Android or iPhone. I don’t at all want to give the impression that I’m a Luddite. I’ve been interested since the short-lived early Rocket Readers in the possibilities of electronic reading experiences. And it is quite possible that I have been stitching shards all these years as a kind of response to and affirmation of the visual experience of reading little chunks at a time of Waiting for Godot on my Palm Pilot in 1997 or so. But my writerly sense of self is still dominated by the exigencies of post-scroll pre-smartphone reading technologies and I’ll likely keep principally attending to them, both consciously and not, as I continue to work on my central preoccupations: memory and narrative and fiction and prose.

The subject matter of Kind One explores race and gender in antebellum America and as far as I am aware, this is the only novel you’ve written that primarily takes the perspective of women. Additionally, the novel spends a significant amount of time in the perspective of a woman of color. The portrayal of the main characters is not objectifying, degrading, self-congratulatory, or facile—though there is a remarkable shared stoicism to their voices. As a white male author who began his career at the height of identity politics in America, what was the impetus to take the perspective of the other? What challenges did you face in your process in writing these voices and characters?

I recently found myself in conversation with the excellent writer and editor Kate Bernheimer, who made the comment, about Kind One, that it must have been really hard to write. Which it was. And how much harder, of course, infinitely harder, must it have been to live these things that the novel evokes. Peter Warshall, an early mentor, whom I served as a teaching assistant at the Kerouac School in Boulder, reserved the highest place in his vision of things literary for those novels that took on the most complicated quandaries and deepest moral dilemmas and most difficult situations. He spoke of Malcom Lowry’s Under the Volcano and Faulkner’s Absalom, Absalom among a good number of other books.

I think of this because for a number of years I felt like some of the greatest writing challenges that an American might usefully take up were cordoned off for me. It was the mid 1990s and I was expressly told by my peers in writing school that I must not, under any circumstances, write the other. That if I did this I would be perpetuating a violence that was very real and very much ongoing. Plus as a straight white male I could never convincingly enter the head of someone who was unlike me. It would be a joke. A violent one. I am nothing if not attentive to the concerns and feelings of others and for years I took this injunction as an opportunity to avoid a fearful trespass. Also, somewhere along the line, most probably upon the publication of Beloved by Toni Morrison, it came to seem as though slavery was something only writers of color could legitimately address, in the way that the Holocaust seemed a subject that only survivors and their descendants had the right to take up and wrestle with in all its awful, heart-wrecking depth.

No doubt the work of W.G. Sebald, who as a gentile and son of a Nazi soldier wrote at length and compellingly about the Holocaust and its after-effects in Germany, put into my mind the idea that I might take up or try to take up the subject of antebellum chattel slavery and its legacy, which after all still sits dead center in the national psyche, and with so much still to be considered. In that context, I remember a comment made in passing by Tony Horowitz, that there remained so many, many unexplored stories about the Civil War, its antecedents and aftermath, and that too had an energizing effect on me. More than anything else though it was the voice of Ginny Lancaster which came spilling one day off the tip of my pen, and the other voices it gave birth to, that called me to this work. And maybe, thank God, I had aged out of being afraid of offending the vocal members of my workshops who were still and are still (in my mind) telling me not to do this and that.

The novel is very aware of power in human relationships and moreover intimate power is unstable. There’s also a bit of a mockery of constructed power roles at work (for example, when the main character though barren must be referred to by the black slaves as ‘mother’ per the rules of her tyrannical husband). It occurred to me while reading Kind One that ceding or taking power is often an intellectual act—something that requires a certain amount of deliberation even in the face of coercion and pure force—as humans, as primates, we’re always very aware of power. I suspect that one of the great misunderstandings of oppression are the internal calculations of both the oppressor and the oppressed. Internal language, which is best accessed and portrayed via literature, is possibly the most effective way to portray the long-term, conscientious, internal processes of oppression artistically. How does one go about exploring and then depicting the inner lives and reckonings of an oppressor and of someone who is oppressed?

This is lovely in that it speaks its own answer even as it formulates its question. There is self and then there is awareness of self and we all have both even when we are shackled, even when we snuggled down by choice in a cold frame by an outhouse. An editor at a major publishing house who has now gone on to edit a famous literary magazine read the central narrative of Kind One (Ginny’s tale), which for a long time was the whole book, and commented that he could not believe in this poor, rural woman’s voice. It does quite a lot of work this poor, rural woman’s voice, and perhaps it seemed to him that it did too much. All the voices in the book are set to work and to speak complexity in their different ways. Attention to the shallow and deep parts of the pocket both, to borrow a bit from Ginny, seems crucial in this. I imagined Ginny as simpler and more complex than it was reasonable for her to be. I imagined all the characters in the novel in this way. Their voices are pushed past reasonableness, towards reticence, towards hyperbole. As the subject of slavery required that they be. There could be no easy middle ground. Just as there could be no clear conclusion. They were and are in a vortex.

In that vein, the image of masculinity in Kind One is complicated. The novel in fact begins with a short vignette from the perspective of a farmer who is digging a well. The portrayal of this character depicts a rich inner life including the expression of emotions and self-awareness about the delivery or withholding of violence (particularly in regards to his wife and child). This gentler depiction of masculinity is counterpoised to the brutality of other straight, white, male characters in the text and thus there is the implication that the qualities of violence, domination, and cruelty are not intrinsic to male identity. If depictions of the other, particularly when beheld by the gaze of privilege, must shift, must the image of privilege (in the example of Kind One, masculinity, whiteness), shift as well?

If writing, if literature, has work to do, and I believe it does, it is in this domain.

Though primarily realistic, there are flights of surrealism, which are frequently in response to trauma. Zinnia and Cleome teach Ginny about the escape of the mind, which she is already very amenable to from her love of books. Alcofibras is called upon to deliver oral stories. And when Ginny is imprisoned and near death, she experiences flights of the mind. Thus, imagination is held in direct contrast to trauma in Kind One. What is the role of imagination in the contemporary mind (a mind inundated with technologies and mass marketing, a mind frequently confronted by the trauma of war and poverty warped by the often false sense of distance)?

Even as I make reference above to the challenges facing American writers, I do not fool myself even for a minute that the corporate advertising-driven gadget nightmare we are building for ourselves is any more urgent, or rather anywhere near as urgent, as the nightmares of illness and poverty and environmental devastation and war that so many people on the planet are facing. The endless cavalcade of apocalypse books and shows remind us here in the west that we are always only a meteor or virus or nuclear weapon away from a return to the “old ways”, to lives that are “nasty, brutish and short” to borrow a bit from Leviathan. Too many people are already and still living with seemingly incommensurable challenges, like how to find a drink of water that hasn’t been polluted beyond hope of recovery, and while I would never presume to suggest what would be most helpful or useful in these contexts (which also play out here, daily, in the richest nation in history), I do know that every one of us can and does imagine, and that it is the imagination and the closely related faculty of dreaming, whether controlled by fear or joy or desperation or tech-enabled passivity, that can and does still allow us to be both here and elsewhere simultaneously. And that is something.

Similarly, the role of parable is crucial to Kind One, though unlike traditional parables, the lessons of Kind One are often ambiguous in their final statements and more seemingly invested in creating an emotional or psychological texture. Most striking of these is the parable of the skulls with flames who hunt all the other animals out of jealousy, as told by Cleome. This story doesn’t offer a lesson in the sense of prescriptive advice and rather endows the real world with both magic and evil. What is your interest in parable? I can’t help but think about how children’s stories are often allegorical, so—were you told parables as a child that have perhaps influenced your sense of narrative?

If you have read the Palm-Wine Drinkard by the late Nigerian writer Amos Tutuola you will recognize the skulls, though his are up to different things than Cleome’s. Almost since I started writing I have been interested exactly in the textures as you describe them on offer in fables and folk tales. As often as not the ones I have been exposed to are non-Western in origin and they move in different ways and with different rhythms than we are accustomed to encountering in the works, say, of the Grimm brothers or Hans Christian Anderson. The stories my characters tend to tell or that exercise their imaginations are like parables or fairy tales with their moralizing ends broken off. Tutuola’s stories within stories tend to function this way. I was never much interested as a kid in the moral conclusions in Aesop’s or LaFontaine’s fables, but the worlds they evoked burned new pathways in my brain. Those new pathways had the curious virtue of leading me straight into spaces that felt very, very old.

What forthcoming works do we have to look forward to?

I am working on a collection of autobiographical essay-stories that admit fiction to varying degrees. I’m thinking of borrowing and adapting the subtitle of the short novel I just co-translated from the French. The book, by Arno Bertina, is called Brando, My Solitude, a biographical hypothesis. So I might call this book, Runner, a hypothetical memoir. I’m working on other books too, at least one of which is a novel, told from a woman’s perspective, set in the 19th century.

Getting free books and drinks rocks especially if you’re a creative type hauling 16 tons getting another day older and deeper in debt, but what about free art?

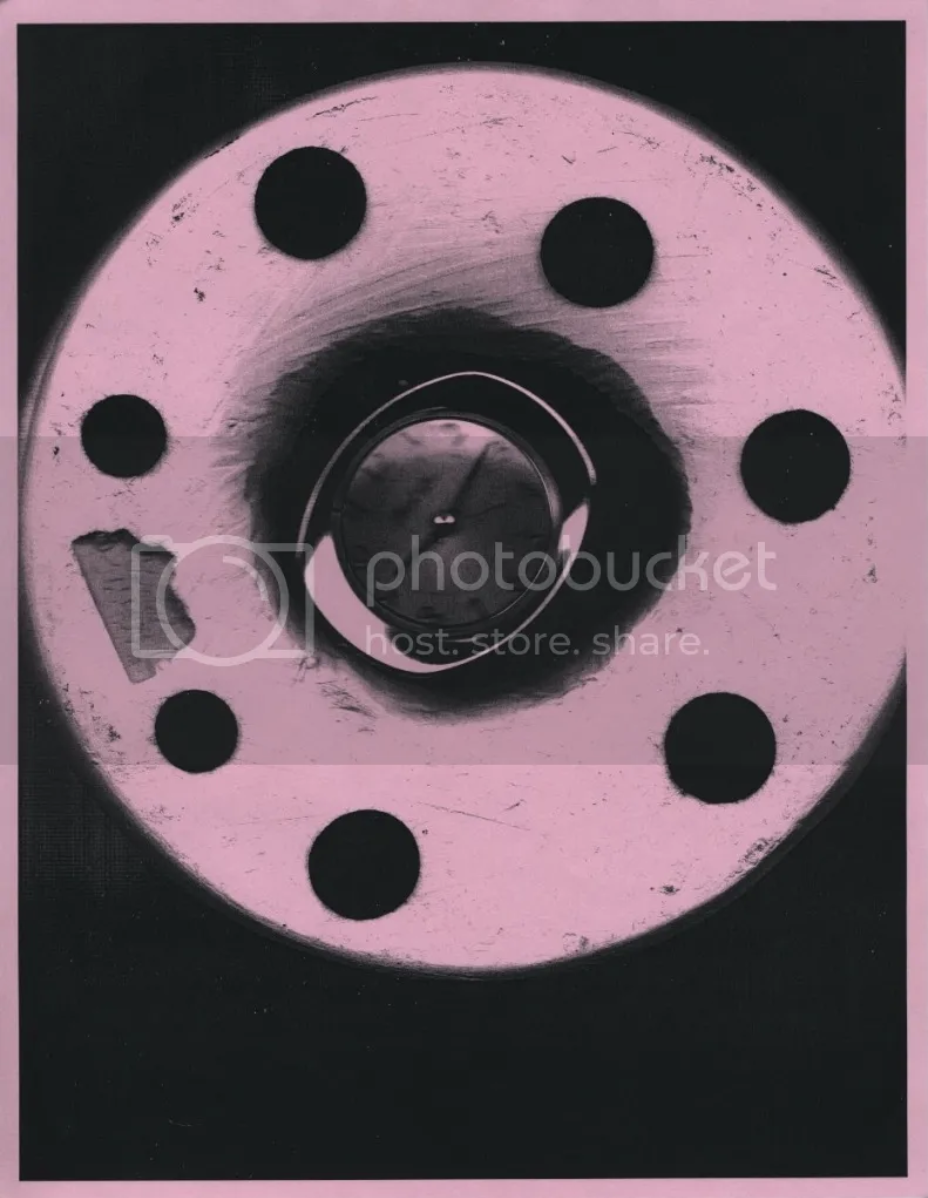

Last weekend, Heliopolis in Greenpoint opened a new exhibit, “Witness My Hand,” by Paul Ramírez Jonas where one can take a photocopy home for the effort only of pushing a button. The photocopier that replicates/creates reams of the work is the pedestal in the installation and Ramírez Jonas refers to the items on the photocopier as a “sculpture” calling into question what exactly among artist, viewer, photocopier, original and photocopy is the actual objet d’art.

The experience of the exhibit is a bit like going on a vacation: you arrive at the compact, bright gallery space, realize that the rules are a bit different because omfg you get to touch stuff, anxiously watch other visitors make photocopies first and then perhaps as the adventurous type choose to play along and make your own photocopy. You study your acquisition a bit over your glass of wine in a plastic cup before folding it away into your coat. It’s only later at a bar when you reach for your wallet or perhaps when you’re rifling through your pockets looking for your cell phone that your fingers stumble upon the paper again, and you remember there is art on your person. You have this memento and by virtue of where/how you acquired it, you’re not exactly sure what to do with it. Does one frame it? Tuck it in a box of miscellanea? Hide it in a jewelry chest among earrings and other trinkets? Throw it away (gah)?

This disorientation of where art is located, in which art is neither literally out of reach, nor truly owned by the audience, teases out anxious questions around the art economy. What is the real value of an art object (and in the damaged world economy what is the value of any object)? Who determines the worth of a work of art? Who owns art? Perhaps least asked, but most crucially, how is art distributed?

Along those lines, the title of the exhibit refers to the occupation of notary (one who bears witness to originality). It would be a reach to interpret “Witness My Hand” as a direct statement on the increasing controversy (and yet dubious legality) of copyright violations from illegal online file sharing. Yet a packed opening reception surrounding a photocopier—nearly a beast of an antique—that visitors use to self-serve pieces of art as from a candy dispenser, does imply the freedom of information/technology activism’s take on the Bacchanalian spirit.

Ramírez Jonas’s particular iteration on the subject of art business and art spaces, of which, it should be noted, much has been said that ranges from the impressive to the foolish since Warhol, is successful significantly because the work is sincere, playful and thoughtful rather than cynical, snarky or final. Most of all, “Witness My Hand” comments on art without being exclusively about art economy, nodding just as heartily at the basic joy of engaging with whatever happens to be on the pedestal. Can this variety of joy be commodified? At “Witness My Hand” art isn’t actually free, but it is a sly gift, that is, should you choose to reach out and take one.

“Witness My Hand” is on view at Heliopolis through March 24th.

Interview by Rachel Cole Dalamangas

Is part of your interest in creating paper copies of a sculpture about comparing 3-D and 2-D compositions?

Not at all. My interests is not so much in me making copies as the viewer making copies. How is the art of looking different or similar to making copies, in fact to making. I am not claiming that they are the same or different, I am merely trying to create a situation where the viewer becomes an engaged part of the public. The choice to make, or not to make, a copy is what I hope will establish a relationship between the public and the sculpture. In fact I am interested in conjugating the word public: to make public, to publish. That is what both a pedestal and a copier do for the original, they publish it, they make it public.

In the conceptualization of this piece, how important is audience reaction and how do you anticipate audience reaction?

In the 90s and into the 00s I made worked that kept flip flopping between works that were predicated on participating and looking. When I achieved participation I always feared I had only accomplished some form of entertainment; and when I relied on the more Apollonian mode of viewership, the work seemed too distant. For the past few years I have settled for a kind of potential participation. In these situations the public can participate; but the artworks can function with you or without you. I want the choice to be important, to be felt. I want a threshold, however small, to be crossed by the viewer—and always—I want the option for the public to rescind their participation.

I believe that was your daughter at the opening with you? From what I know of you work, it occurred to me that there’s a playfulness that possibly engages the perspective of a child. How does your daughter react to your work?

She is very critical. Most kids are. If I see my daughter’s eyes, or her friends, glaze over and loose interest in what I am working on . . . I know I am in trouble.

The title “Witness My Hand” suggests that neither the pedestal (copier), sculpture (book), or photocopies are the artwork, but rather it is the audience observing the interactions of these elements. In some ways, the art object of your piece at the Dikeou Collection, “His Truth Goes Marching On” is in actuality the song that can be played and the different ways it’s played by different viewers, rather than the (quite beautiful) chandelier of glass bottles itself. What, to your mind, is an art object?

That’s an easy one! I would have to place myself squarely in the camp that the art is in the relation between you, me, and the object between us. Borges said it best:

The fact is that poetry is not the books in the library, not the books in Emerson’s magic chamber. Poetry is the encounter of the reader with the book, the discovery of the book.[i]

[i] Jorge Luis Borges, Seven Nights (New York: New Directions Books, 1984), 80.

How was the content for the sculpture that would be photocopied chosen? What is its significance?

The bust of Psyche was selected in a rather straightforward way. I simply looked at what was available. I thought that supply and demand would reveal what busts and what statues remain aesthetically and culturally significant to us as a culture. I hoped that whatever high quality reproductions are for sale will actually reveal this. So while I would have loved a bust of Piero Manzoni or Che Guevara, I instead had to choose between Psyche, Freud, Mozart, The head of Pericles, Michael Jackson, Ronald Reagan, Obama, etc. I inserted a clock in the concealed hollowness of the bust so the copy would not only show you the only part of the “sculpture-in-the-round” that we never get to see, but also the present time.

The second object is a statue of an open upside down book. In some ways it is very simple: it is what it is. It is also an inversion of one of my favorite kind of headstones at the cemetery: the open book.

A photocopier seems almost archaic with the technological revolution of the last five years alone. The reference to the origin of “notary” and the mention of copy centers in the press release suggests that you are, as an artist, observing an arc of technology especially in regards to how we relate to art. How do technology and art interact?

I seem to have a strange ability to become attracted to technology just as it is about to die. I am working with admission tickets just as they are becoming hard to find. However, the way we interact with technology is such that even the most up to date gadget will be nostalgic and outmoded within a few years. With the copier I had the initial instinct to use a 1963 Xerox, the first desktop plain-paper copier, I have no idea how many hundreds of thousands were made . . . I could not find a single one for sale. In fact I only found a handful in museums. My apologies, I am totally nerding out on you! I don’t really have an answer to your question. Art and technology are part of our culture and they are inseparable from each other. I just like to note that we take great care in preserving our art history, but our technological history is almost disposable . . . the first web page ever online, for example, was lost years ago. Someone should have made a copy.

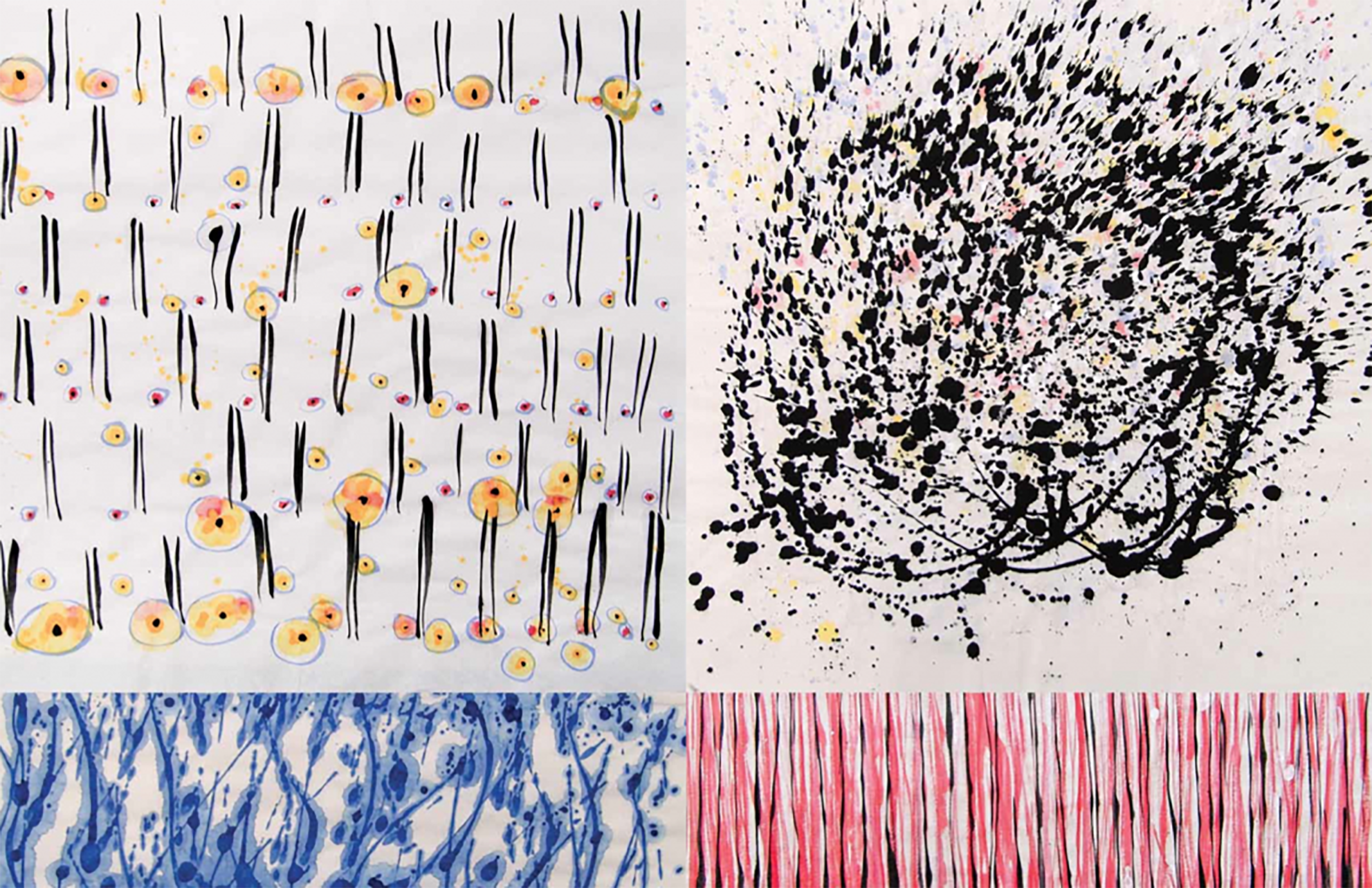

“Mix & Match: Watercolors from Cape Breton” spread from zing #23

From primordial human-scale concrete and cast sculpture made in various abandoned buildings in 1970s downtown New York, to Japanese brushes and watercolor on a remote coastal island, Jene Highstein‘s career has spanned decades, locations, and mediums. Most recently, the Cape Breton Drawings, which introduced color to his notoriously black palette. Moving from the terrestrial to the atmospheric, these works bring the viewer to the “magical landscapes” of Cape Breton, Nova Scotia. The Cape Breton Drawings are currently hanging in a solo exhibition at ArtHelix in Bushwick, Brooklyn. The drawings will also be featured in “Mix & Match: Watercolors from Cape Breton” in zing #23. In person, the man is a witty visionary, sharp of thought and full of personality—first hand experience of what this generation was about: achieving greatness, and having a great time doing so.

Interview by Brandon Johnson

What is the significance of Cape Breton to you personally?

My mother’s family is from Wilmington, NC and I spent my childhood summers on a beautiful white sand beach on the Atlantic. That experience was very moving. We would go to the beach early in the morning and spend all day in the sun swimming in the ocean and fishing off of a long wooden, and later, steel pier, which jutted far out into the Atlantic. We caught a myriad of fishy creatures, which we brought home for supper.

Meanwhile many of my friends had bought property in Cape Breton in the late 1960s, but I had never visited. Among them are my cousin, Philip Glass, and friends Bob Moskowitz and Hermine Ford, Joan Jonas, Rudy Wirlitzer, and Lynn Davis along with many others.

In 2002, on a lark, I took my son Jesse with me to have a look and fell in love with the place. It is very much like the NC experience in that the beaches are quiet, family-type places with few people, but the main difference is the remoteness and wildness of the landscape. The weather is relentlessly changeable, coming from one of four directions in turn so that in one hour the light changes dramatically. The color of the sky, sea, clouds; the fog rolling in and out, the rain coming and going all make for an amazing display of light and color and intensity of sun.

The Black Splash Drawings from 2007 (especially “Gesture (Nature)” and “Atmosphere”) seem to be precursors to the Cape Breton drawings. What initiated the Black Splash Drawings?

I have mixed my own black watercolors for many years but used them on traditional etching and other fine art papers. In about 2004 I began to experiment with what we call rice paper and the Chinese call Yuan paper. These are very different materials with extremely different reactions to the water element in the watercolors. Being in Cape Breton, so divorced from the NY art world and its taboos AND being a sculptor with no real inhibitions as to style and the history of painting, I was freed from all those constraints. I had used Chinese brushes for many years and am comfortable with their extreme sensitivity and ability to convey complex emotional charges. I began to use a kind of splash technique and was intrigued by it. That’s how it began to dawn on me that that technique could work. Over time I was able to become freer and freer with it and continue to do so.

What brought you to watercolor?

In the 1970s I used dry pastels for my black. In the 1980s I switched to black chalks, but by the 1990s I began to mix my own watercolors from bone black pigment which gave me the most dense velvety black that has become the basis of all my two dimensional works.

You have described your earlier sculptural work as not being based on natural forms but evolving in relation to nature, carrying natural associations. Can this also be said about the watercolors?

Yes, I suppose so. The watercolors came about from the intense saturation of my visual world when I went on long walks with friends in the remote areas of Cape Breton. These experiences were also reinforced by exploring the local beaches and bogs, which turn up equally unexpected encounters. The resulting watercolors are not so much impressions of these experiences but perhaps meditations on them.

Many of the pairings have horizontal lines dividing them—are these horizons?

The works are evolving. The more recent ones have a more defined reference to sea, sky, land and water but it’s a fluid transition because one’s experience of these areas is very fluid since they are constantly shifting, making it difficult to say which color or atmosphere would be associated with which . . .

What role does perception play in this series?

That’s an interesting question. In traditional Chinese landscape painting, as I understand it, the artist goes to the site and spends time there but doesn’t make any work. They return to their studios and indirectly interpret what that have experienced. Also, there may be elements of poetry or other language-based parts of the story, not to mention all the seals and comments of the subsequent viewers of the works.

My approach is also indirect in that I set up a studio in the dinning room of our house and began to work there with no particular plan. The work evolved every day on its own without too much intention on my part. It has become increasingly complex and dense in color, but I don’t think it has become more specific in reference to nature. My friend Hermine Ford looked at them and said, “I see, these are looking down, these are looking straight ahead and these are looking up.”

Your project in zing #23 features sections of the Cape Breton drawings paired with one another—4/5 one drawing and 1/5 the other—”mixed & matched” so to speak. Can you explain the thought behind this format?

“Mix and Match” seemed a good way to present a complex subject in a simple way. There is now a large body of the Cape Breton Watercolors, which span the simplest to the most complex ideas so I thought that I would scan through a lot of the images and see if somehow they could be paired into two sets of 4/5-1/5 images on facing pages, which would make sense. I’m happy with the results.

Photo by Dieter Hartwig

Fabian Barba was born in Quito in 1982. He began studying modern dance at the age of 12 in Ecuador. From 2004 to 2008 he studied at PARTS school for Professional Training in Contemporary Dance in Brussels, where he works and resides today. Recently, he was invited to perform his solo work A Mary Wigman Dance at MoMA in conjunction with the exhibition Inventing Abstraction, 1910 – 1925.

Interview by Josh T. Franco

We met in the context of the collective Modernity / Coloniality / Decoloniality (MCD). The particular occasion was a two-week Summer course convened by Walter Mignolo in Middelburg, Netherlands. You were searching for company in thinking about particular questions you had of your discipline, dance, that you had not yet found. Did you find what you were looking for in Middelburg?

During the last three or four years I’ve been trying to make sense of my experience as a dancer who first trained in Quito (Ecuador) and then continued studying dance and working as a dancer in Brussels (Belgium.) In a way I see myself as someone who, through training, came to belong to two different dance traditions, two dance traditions that are not completely foreign to each other but that have established very complex and puzzling relations or non-relations.

During the summer course special attention was dedicated to the question of “decolonizing aesthetics,” a conversation that put into my horizon questions I had not even considered and that I could suddenly discuss with artists coming from different disciplinary and cultural backgrounds. To be immersed in that dialogue was an extremely exciting experience that I haven’t finished assimilating; a very disturbing experience as well, because it further upset the already shaken ground I was and am standing on.

And yet, it was not only finding a common interpretive frame for thinking about different though related experiences that produced my disturbing excitement. It was also the sensation that my personal experience and the personal experiences of the people I met were placed first. We were talking theory, but only because in different ways we need that theory to make sense of our disparate yet related stories.

When I met María Lugones, I met a person first, a person whose voice was present later that summer when I read her Pilgrimages/Peregrinajes, a book that I’m sure won’t leave my thinking untouched. When I met you and you told me the story of Marfita, I was just amazed because even though our life experiences are quite distinct, I could somehow recognize in your story something like my dislocation working in Brussels, trying to make sense of two different and seemingly unrelated worlds. Then I also remember talking with Rolando Vazquez in María’s hotel room, telling him about my struggles to establish a relation with past and history that wouldn’t deny my former experience as a dancer in Quito, and he saying with his kind smile “so funny, I’ve been writing about it for a while now and here you come with this,” then of course I got to read what he was writing and that brought into my practice a perspective I haven’t been managed to articulate, a perspective that carries the kindness of his smile, a kindness that dissolves the discomfort that often accompanies the word “colonialism” when it appears in conversation with my colleagues in Brussels. Then there’s also the sensation of understanding something of the political commitment of Walter and his project of decolonizing epistemology, a political project that involves him fully as a person. So yes, I think I found the company I was looking for. A very warm company. And yet a very disturbing company for the questions it raised. For example, what does it imply to “decolonize aesthetics”? We certainly didn’t have the time to get to the bottom of that.

On February 1 of this year, you performed your work A Mary Wigman Dance Evening as part of MoMA’s ongoing series, Performing Histories: Live Artworks Examining the Past. You were invited to perform in conjunction with the exhibition Inventing Abstraction: 1910 – 1925. Can you describe this piece, and give some history of Mary Wigman herself?

Mary Wigman is an important figure in the history of dance. She is recognized as a main character in the development and consolidation of Ausdruckstanz or “dance of expression.” She started to create her dances in the mid 1910’s and continued working all the way into the early 1960s, passing through the Weimar period, WWI, the interwar period, the rise of Nazism, WWII and the years after 1945.

I will just briefly point out that at the beginning of her career she engaged in an artistic practice that sought to strongly challenge the predominant values of the bourgeois society from where she came. In many aspects what she did must have been shocking: an adult woman (she was almost thirty at the time of her first public performance), single (maybe engaged in a love relationship with another woman), seeking a career of her own, doing dances that lacked gracefulness and that sometimes were performed even without musical accompaniment… She didn’t have it easy the first years. However, from the early 1920s on, she gained recognition and an important place within the dance field in Germany. In 1930 she made the first of her three tours through the United States, where she was received as “The Goddess of Dance,” a real diva whose work seemed revolutionary while enjoying wide popular acclaim. From 1933 she continued working in Germany under the bureaucratic and ideological machinery of the National Socialist party. Her personal stand in relation to nazi policy is a heated subject of discussion. For now, I will only note that a clear change in her artistic production can be noticed—how much of it meant resistance or accomodation to the regime is to be analyzed calmly. You can find a very exhaustive and compelling study of Wigman’s work in Susan Manning’s book Ecstasy and the Demon: The Dances of Mary Wigman. For my work I focused on the first tour of Mary Wigman in the United States. Her performances resembled a music concert, something like an MTV unplugged. The evening was composed of about nine solo dances, each of them had a length ranging from three to seven minutes. Each dance had a different costume, there were two live musicians accompanying the dance. Some audience members would know Wigman’s dances as we might know a pop song, and they would ask to the theatre to include this or that dance into the program, which they did.

A Mary Wigman Dance Evening is a theatrical proposition to imagine how one of those evenings might have been like. I learned three of her solos from video . . .) I also studied principles of movement developed by Wigman with three of her former students who worked with her in Berlin in the ’60’s.

I am thinking about your performance in the context of the exhibition Inventing Abstraction, 1910-1925. Based on our conversations this summer and since, the history of abstraction seems like only half of the story in your thinking about A Mary Wigman Dance Evening. Your other, primary concerns have to do with your particular appropriation of her work in the 21st century, as a male-identified body from Quito, Ecuador, who has lived in Brussels for significant portion of his adult life as a dancer. And all this specificity is perhaps at odds with the premise of the exhibition. How do you see your concerns in relation with the history of abstraction?

Reading texts on decoloniality and post-colonial theory, I became familiar with the critique of un-embodied, abstract Reason and Knowledge. That is, the detachment or abstraction of the thinking subject from the situation s/he studies, as if s/he was placed in a privileged a-temporal, out-of-space point of view.

As far as I know, Wigman and her contemporaries referred to the work they did as pure, abstract dances. At first, that sounded as nonsense to me. To my understanding and sensibility, those dances were anything but abstract. Through my education I had come to recognize abstraction in Merce Cunningham or in Yvonne Rainer’s Trio A. Wigman dances had too much emotion, too much of a pretense for transcendental meaning for me to grant them the status of abstract dances. However, later I came to understand that abstraction for Wigman meant that her dances, or most of them, tried to do without recourse to narrative: there was no story-telling, no pantomime, no identifiable characters. This is how I now understand Wigman’s understanding of abstraction.

At the same time, Wigman was doing a new German dance (Ausdruckstanz). However abstract she claimed her dances to be, they were supposed to express a way of feeling of the German Folk, a Teutonic German Soul, a belonging to a German Soil. There was a strong nationalism in Wigman’s work from the ’20s on that I think doesn’t give much room for the kind of abstraction of the detached, disembodied ‘thinker.’ (This kind of nationalism of Wigman’s early work shouldn’t be immediately conflated with the nationalism of the nazi regime. A great majority of modern dance practiced in different European countries and in the United States was unmistakably nationalistic, including Martha Graham’s work who later forcefully participated in a boycott of a dance festival sponsored by Goebbel’s ministry.)

Certainly, my work focuses strongly in the relation between a dance practice and the cultural context in which it is produced. In a way, contemporary dance could be understood to be a very abstract artistic practice, detached from any specific location. Even if it tells a story or depicts characters, contemporary dance might be understood as a “universal language” as if thanks to its independency from spoken language, everyone could access it. If contemporary dance would be indeed a universal language, it wouldn’t be attached to a region nor to a community of practitioners nor to a specific history; everyone could do it, everybody could join either as a dancer or as a spectator. And this is not false: anyone can join, but at the price of inscribing oneself into a specific dance tradition. A dance tradition that is historically and geographically specific. Contemporary dance is not a universal practice, though it might pretend it is.

Or, there are several traditions of contemporary dance. When I was in Quito, I was doing something we used to call contemporary dance and then I decided to go to Brussels to improve my contemporary dance technique; I thought I would learn to kick my legs higher, that kind of thing. However, through my technical education in Brussels, I noticed later, I inscribed myself into a different dance tradition than the one of which I was a part in Quito. Through learning to use my body differently, I also learned to think of my body differently, and also to think differently about the role of the dancer and of the definition of dance itself. I didn’t improve my contemporary dance technique in the abstract; I became part of a different dance tradition, a very concrete one.

It’s the relation between these different dance traditions that interest me, dance traditions that are practiced in very specific cultural contexts. They’re not artistic practices that dance freely in the air, nor that are despotically rooted to a nationalistic soil.

You have spoken repeatedly about the relationship of time and place playing out in the fields of Modern and contemporary dance; how work from non-European, non-metropolitan companies is often relegated to an elsewhere time. You have been struck by comments like “that’s so 80’s” from prominent dance critics in regard to some of this work. Johannes Fabian called this the “denial of coevalness,” when geo-politics are articulated temporally, relegating a group or activity to a primitive status. It’s a way of maintaining legacies of coloniality to the benefit of those in old power centers. But you have argued that if we look to the specificity of experience and production in these sites instead of reading them through the terms of these centers—so that they appear merely dated—we might arrive at very different conclusions and possibilities. What might we achieve through such an examination, specifically?

I want to make something clear. When I talk about contemporary dance I refer to a specific kind of dance: artistic dance that is created for the theater (as institution and/or physical space). Thus, the epithet contemporary (which I write in italics) names a kind of dance which has to be differentiated from the adjective “contemporary” when this refers to the belonging or occurring of something in the present situation. So contemporary dance (without italics) could be any kind of dance practiced in the present situation: ballroom dances, street dances, etc. The curious thing is that contemporary dance, at least nominally, claims the present for itself excluding from it other kinds of dances. To my understanding, contemporary dance not only says that it belongs to the present, but that the present belongs to it; contemporary dance places itself in the ‘now,’ it colonizes the ‘now.’ Nominally, modern dance wouldn’t be contemporary, and it risks being placed as part of an overcome past.

Modern dance in Quito is not the same as contemporary dance in Brussels. The kind of modern dance I practiced in Quito could be accurately described as modern dance in that its technical, aesthetic and ideological premises filiate it to other modern dance traditions as they have emerged in different parts of the planet. To say that the dance I practiced in Quito is modern is not a problem by itself. The problem is when the contemporaneity of modern dance is denied. The main problem with this, is that if modern dance in Quito is an anachronism, then the only thing left for it to do is to “catch up” to the present exemplified in the work created in the centers. This thinking parallels this sentence by Marx quoted in Chakrabarty’s Provincializing Europe: “[the] country that is more developed industrially only shows, to the less developed, the image of its own future.” This would annihilate the capacity of dancers in Quito to define their own artistic project, subjugating their practice to the assimilation of a project designed elsewhere: coloniality at its purest!

Something important I haven’t made clear this far: I became interested in Wigman’s work when I was in Brussels because in a way it referred me to the kind of dance I used to practice in Quito (mainly due to the central place given to emotion and intensity in both dance traditions: Ausdruckstanz and modern dance in Quito). The problem that appeared from the start is that I set an equivalence between a dance tradition that belonged to the past (the 30’s in Germany) with a dance tradition that belonged to a place outside the boundaries of Europe and the United States (Ecuador in 2000). It was as if traveling outside of those metropolitan centers meant traveling back in time!

The master narrative of dance—before it starts to be critically rewritten in the early 80s by dance historians—said that in the beginning there was ballet. Then early in the 20th century early modern dance appeared in opposition to ballet, with dancers like Ruth St Denis, Laban, Wigman and Graham. Then starting in the early 60’s, Cunnhingham and the dancers of the Judson Church in New York propulsed the post-modern dance (in clear opposition to modern dance) that gave place to the effusion of contemporary dance.

Although this almost caricatural presentation of the master narrative of dance history can easily make me target of harsh criticism, I think that that master narrative, however contested, remains operative in a surreptitious manner. It is this historicist, stagist account of dance history that creates the conditions of possibility to say that modern dance is not contemporary, an anachronism because modern dance came before contemporary dance, and in historicist thinking we’re faced with a sequential logic instead of an additive one: contemporary dance has to displace modern dance, they cannot exist at the same time—thus the denial of coevalness operating in the fight for the ‘true present’ in dance history.

When I started working on A Mary Wigman Dance Evening, I related the kind of modern dance I used to practice in Quito to a tradition that was not recognized as a living dance tradition in 2000—as far as I know, there’s no one actually practicing Ausdruckstanz in the way it was practiced from the mid 10’s until circa 1965. In that sense, the shortcoming of my thinking was that I related modern dance in Quito not only to a past dance tradition (exemplified in the work of Wigman in the 30’s in Germany), but also to a dance tradition that lacked vitality. However, even if Ausdruckstanz couldn’t be considered a living dance tradition in 2000, it did influence enormously the development of different traditions of modern dance, which maintain a living practice that is not relegated to the past even if they are very aware of their genealogy. Thus, when I was considering the filiation between Ausdruckstanz and modern dance in Quito, I could have focused not only on this genealogy, but also in the relations that modern dance in Quito could establish with other contemporaneous modern dance traditions as they’re practiced in different parts of the planet. Examining the specificity of modern dance in Quito doesn’t mean to deny its filiation to Ausdruckstanz nor to isolate it as if it has come out of a vacuum, it can allow instead to recognize its autonomy and capacity for agency in relation to different living modern dance traditions as places that are presently inhabited by dance practitioners that need not, should not, be relegated to an archaic, objectified, detached past.

I am frequently struck by your use of the phrase “embody dance” in regard to dancers you hold in high regard. To the untrained, it seems redundant. Is dance not always embodied?

I usually talk about the embodiment of images, ideas and ideals when referring to the kind of dancing exemplified in the body and practice of a dancer I appreciate. I like to stress the embodiment of ideas and ideals to make clear that these do not exist only in abstract thinking and language, but that they have an existence and a way of transmission that passes through the body.

The dances of Wigman were at first foreign to my body; they existed in videos, photos, textual accounts and exercises I had never practiced. Much of their work is done through verbal language. My approach was the bodily re-enactment of those dances that didn’t exist in the traditional archives. To embody those dances meant to inscribe them in my body, to host them, to give them a bodily existence.

Alison Kuo is a Texas native. She received her BA from Southwestern University in Georgetown, Texas. Her blog Accidental Chinese Hipsters has been featured in Vice Magazine. Currently, she is in her first year of the MFA program at the School of Visual Arts in New York City. We talked in early January, following her solo show Colorful Food at Eleven Seventeen in Austin, Texas.

Interview by Josh T Franco

I am back in New York, just a few days after Colorful Food. I am thinking back to the night; there’s a room with four walls bearing your large format photographs. Some are of food, some are of food abstracted beyond recognition, and some are arbitrary shots, in which the shapes, colors, dimensions echo those of other photographs. These photographs are the only For Sale items, according to the price list at the door. Your food-cart inspired offerings and performance are free. (If we can get free food, why would we pay for photos of it? Oh yes, because this is the art world.)

I’m writing you from my studio back home where I’m surrounded by half-reconfigured snack machines, bags of gummy candies, chips and chili peppers, illustrated cook books, and an overflowing unpacked suitcase filled with plastic fruit serving dishes and shiny vinyl letters. There’s a lot to think about after these two public showings of my new work, and in the runaway train that is a two year MFA program I’ve got to try to fix my eyes on the moving landscape to see where I’ve been, guess at where I am now, and also look to the future without getting too dizzy. Having you as a fellow traveler, one that I often encounter here (New York) or there (Texas), helps me to orient myself, and for that I am grateful. That you’ve responded to my deepest, perhaps concealed, intentions for this rather silly performance is wonderful.

The scene: We are in Austin, at Eleven Seventeen, the home/gallery of our friend Joshua Saunders (the space is his goodbye love letter to Austin before he imminently departs). I saw an earlier version of Colorful Food at your studio in New York a few weeks before. This is certainly leveled up; the colors of the specially painted floor and the incisively hung and glued plastic fruit replicas define the space as a space more successfully. The now wooden (formerly foam core) center-piece demonstrates a solid craftsmanship. The choice to rest it on the unobtrusive and equally well-built rusty, rectilinear base made by Ben Brandt makes formal sense as well as radiating a warm send-up to our Austin-Brooklyn back and forth network. The center structure itself is no longer white, but peach. The labels glitter precisely in gold, begging to be spoken, or sung. The holes they name may well be microphones. Front and center, “You & Me” dominates. Appropriate. Then the performance, or the activation, as I prefer.

Performative artwork is activated when it is shown to an audience, as in the thing/idea becomes alive. I think with good art—a painting, a performance or anything—that stimulation, that electric activity, happens in the mind of the audience. In this project I’m harvesting as many of those new associations as I can by having a conversation integrated into the process. At the same time, this isn’t a laboratory or a focus group. Establishing myself as considerate of every aesthetic experience my audience has plays a big role in the trust I’m trying to create, the feeling that makes it okay to let go of control a little bit and eat the squid cracker with mayo, honey, wasabi peas and pop rocks.

I realized something during too many delayed flights back North. Visually, the space of Colorful Food was fine and striking. And the photographs would do well even alone. Yet, watching others partake, calling their menu selections to you through the according hole, the potential spectacularity was mostly lost on me. The space disappeared, and we were at just another East Side party, not a terrible thing. But when I was the transmitter to your receiver and vice versa, I felt deeply the distortion this work produces. Felt it do what art does. I didn’t feel that power as Colorful Food’s demonstration of a relational aesthetic, no doubt how many are discussing it in these following weeks. I felt its action in the disruption of information.

You are right: the installation and other art-looking things, the party, the fun, is almost an act of misdirection. My interest is in how our personal word choices and mental associations shape our daily transactions (commercial and personal), and in turn how much you or I are really engaging with the people we transact with. I often find myself almost unconsciously thinking: Can I get what I want? Is there something that I don’t know that I want that this person could give me? How do I ask? How can I reciprocate? Is there something I can give back that they want that I don’t know they want? Or that they don’t know they want yet but I can provide? What I’m finding is that the smallest act of willfully sidestepping the familiar way things go in an interaction is liberating. The brain says, hey, you’ve gone off the script, and both sides become present in constructing new language for what’s happening. That opens up possibilities for un-preconceived things to manifest.

Like at a food cart, I could place an order. But unlike a food cart, the feedback you built into the work through a seemingly arbitrary menu of signifiers and the “small talk” you require to round out a customized snack was, as feedback is, utterly distorted. Thus, I discovered the excellence of tangy cotton candy wrapped in purple cabbage. Colorful Food then, surprisingly, was about information, how it traverses through our everyday exchanges—morning coffee orders, buying over-the-counter meds, all (commercial) exchanges—and what distorting it might reveal and produce.

One thing that threw me off about the Austin show: it was loud in there! I didn’t expect that the new snack machine box I built from plywood would be so much more sound insulating than foam core (duh), and also (duh) forgot how bouncy noise gets at openings when lots of people are standing around in one room all talking at the same time. So I had to yell a lot and steal looks at people’s faces through the holes, which made for a different, more visceral feeling for the performance. I’m going to think about your use of the word “distortion” as I go forward. Distortion of language read or heard, of sound itself, of taste, of desire, of appearance, of expectation. Dialing up one type of distortion, isolating and accentuating it, could produce more extreme results. I fear not knowing at what level of dissonance I would lose the trust of my audience, but that’s where I need to challenge myself. Certainly at the Eleven Seventeen closing party in February there will be opportunities to test this out, as I’ll be skyping into my performance.

Again, part of what Colorful Food produced was a great party and novel moments of relating, sure. But what I took away was not about the larger networks of sociality, or feeling like I had participated in a “new” way of producing space. What I took away was the power of the small gesture to focus our attention on the massive flow of (mis)information charging throughout our waking and sleeping lives. What I took away was the ways in which art can recharge how we undertake the daily projects of “You & Me”.

In parting, I hope you eat a kumquat soon. It’s a small citrus fruit that looks like a miniature orange, and you can find them in Asian markets this time of year. First shock – you eat the peel. Then it defies you again by being sweet on the outside and pucker-inducingly sour on the inside. Eat one, and then give one to your friend.