Lessons of New York is an unfinished collection of oral histories from the LES art scene of the 70s and 80s

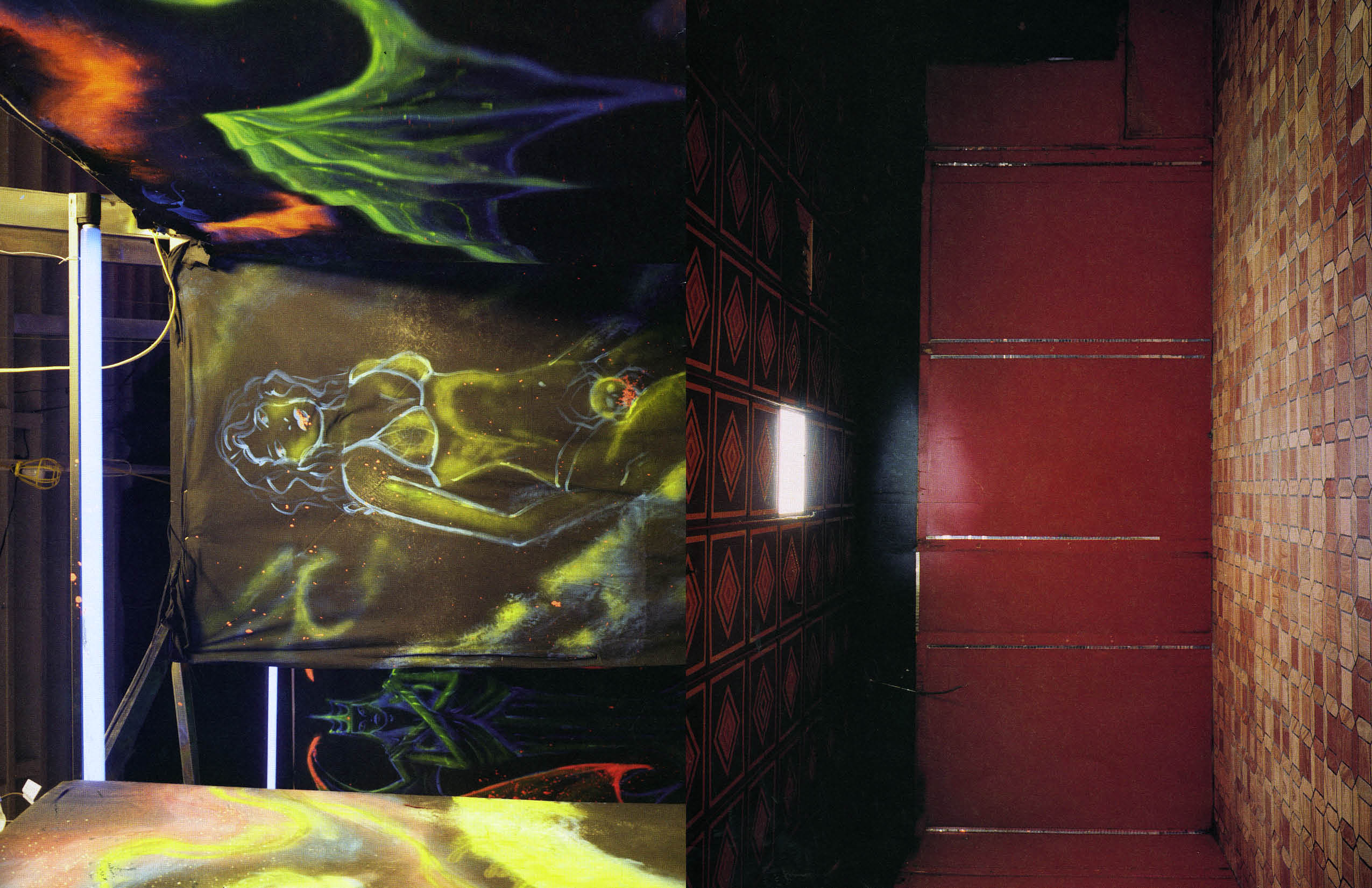

Walter at zing #22 release party in Miami, December 2011

I first met Walter in 2013 when I interviewed him at his LIC studio for zing, shortly after moving from Denver to NYC. I was a walking cliché of a cliché – a young writer in New York.

After the interview, Walter asked what I was doing in the city, and when I told him, he said, “Well, I don’t see you becoming the next Susan Sontag,” then invited me to wander over to some LIC exhibit openings with him.

When I began collecting stories about the LES in the ’70s and ’80s—a sprawling, unfinished oral history for which I interviewed Walter again in 2015—he was incredibly supportive.

“I’m far too lazy for a project like this,” he said.

And, “I’m too shy to call all these people up,” he said, quick to pull out his phone to share contacts for subjects I wanted to interview.

When I occasionally ran into Walter at exhibit openings, he’d give me a cranky pep talk that vaguely had the tenor of a coach trying to motivate a lazy athlete.

“You gotta dig, really dig, ” he said.

“Are you still doing that thing? Keep going,” he said.

I didn’t keep going after about 2016.

I stopped writing about art, and saved the many hours of audio files I’d collected to a hard disk drive that went into a box of files I didn’t know what to do with, where it would remain for nearly a decade of life’s great ups and downs.

American poet Gertrude Stein said, “We’re always the same age inside” – awkward wisdom on mortality that makes me think of this story of Walter – the kid inside the ‘old man’ – newly arrived in New York, catching glimpses of the city through his eyes, looking past the ‘hill’ of Columbia, imagining what awaited him downtown.

Interview and editing by Rachel Dalamangas

WALTER ROBINSON:

You know there’s this notion that we know what we’re doing and we’re in control of our lives, but actually of course we’re not. We don’t know what we’re doing and we’re not in control of our lives. And how I ended up in New York I would say is just an accident. But there must have been something, some psychological thing.

Here I was in Oklahoma. Eldest son of a completely middle-class family. Typical angry, repressive, hard-working father.

And I could have stayed in Oklahoma and lived in Oklahoma and been bored, but somehow, I felt enough out of place unconsciously that I came to New York.

I came to New York in 1968. It’s not the typical story when people come to New York. Most people, you know, they pack their bags, and everything, you know? For me, eh, I just came for college and never left.

I was afraid of the city. You’re cloistered on the hill at Columbia at school and they would tell us, “Don’t go downtown. You’ll get mugged.”

I was really slow on the uptake. I discovered the art world when I was in college and started going to museums and started to go to galleries in SoHo and got caught up in the art business that way.

Where the Twin Towers stood it used to be nothing. It used to be a landfill. There was nothing there. It was like a beach. They’d do performance art there. Martha Wilson would curate it. I saw Sun Ra there.

When I got out of college and moved downtown, my rent was $220, and I think I had a job typesetting. Somehow I got into the typesetting business. Maybe it was freelance for Sing Out magazine. Or maybe it was part-time for this newspaper called The Jewish Beat. I made $6/hour, and I had more money than I knew what to do with.

By the end of the 70s in SoHo, there was this SoHo style painting. Painting that didn’t know what it was doing. Say the dean of SoHo painters was Ron Gorchov. That kind of abstraction. Judy Pfaff for instance is another. People who are still carrying on in abstraction even though it’s been bypassed by newer aesthetic developments.

In the early 80s, I moved to Ludlow Street, and I was hanging out with all my friends from Colab. I had a job. I worked at Art in America, and I guess I was looking for another extracurricular activity. I had been president of Colab and decided to quit I think in 1982.

I had my own painting by then. Now if I had been smart, I would have pursued painting 100%. That’s what I recommend to young people. Don’t get a job. Pursue your art 100%.

I was looking around for another project and somehow, I got the job of being the art editor of the East Village Eye. I guess Leonard asked me if I wanted to do it, and I said yes.

Carlo McCormick was already writing for them and that’s when I met Carlo. He was already writing about the piers. There were a lot of artists that would go over to the piers and insert artworks. I never even went over there. There’s this famous David Wojnarowicz painting of like a giant cow’s head with a tongue sticking out painted on a wall at the piers. They’re all marked out by now of course.

Self-Portrait (after Matisse), 2024

At the East Village Eye, we had a lot of fun writing nonsense.

I wrote a little review of a guy’s show just by looking in the window. I didn’t go in and look at the art and he got mad at me about that.

I had the whole Waltergate thing. You may know about Waltergate. When I stitched together a bunch of press releases and ran it as a column as if somebody had written it. The funny thing was that poor Barbara Gladstone complained and then the art critic Joe Matsheck who was a player in those days wrote in to support me. Judd Tully complained because he’d been misquoted. It was funny because Judd blamed Carlo because Carlo had written the column next to it. It’s all very confusing.

That whole [1983] Whitney Biennial was harshly criticized as being the “East Village Biennial.”

That’s when it became clear to me the scapegoat that the East Village was becoming for all things that people thought was bad about art. “The New Art’s too stupid or too gaudy or somehow meretricious.” “The East Village is only about money.”

Conservative forces, whether it’s Robert Hewes or writers for October magazine would attack the East Village and attack the Biennial as the East Village Biennial even though in fact there were only a few artists associated with the East Village in it. Most of the artists from the East Village have never been recognized by the museum structure.

The East Village represented these upstarts, these upstarts who are bad.

But you can’t say the same thing was true about Keith and Kenny and Jean-Michel. They were the triumvirate.

Keith was a star before anybody even knew who he was because he was doing his Radiant Child barking dog graffities all over on plywood in construction sites and on the subway and people really liked those. Even though there was a big graffiti movement, his stuff is really not that vandalistic. Like a lot of the graffiti writers would write all over the trains. So he was already very popular with the people.

And then when Jean-Michel had his first show, there was this intense buzz. Everybody loved that. Really came out with his first show at Anina Nosei in SoHo. Tremendous buzz about it. That was the show where he was supposedly locked in the basement and kept painting. Everybody just loved that stuff.

So Kenny’s adaptation of a Hanna Barbera look fit totally in with whatever it was that was happening this 80s – the American 80s painting revival.

It’s also part of the Tony Shrafrazi aesthetic.

Tony had a bunch of other artists that are kind of forgotten now. Like Brett De Palma, Ronnie Cutrone. I think what happened to Ronnie was that he wasn’t focused enough on the art business because he was too much of a drug addict. The art world can be harsh on people who are drug addicts, people who get a reputation for being junkies.

There’s nobody like Tony. He’s a little bit insane now, I think. He’s really enthusiastic about art. He’s very meticulous. That’s why he loves Jeff Koons so much. Because they share almost obsessive-compulsive meticulousness. Tony’s the kind of guy who has to have an assistant to wait around for him because he doesn’t really know how to lock up.

In the art business, you want to be known as the go-to person for something. The art world is full of go-to people.

You have to have your eyes on the brass ring and you have to go for the brass ring. You can’t be satisfied with sitting in the back of the background.

I was talking to a writer that used to work for me the other day. I had been looking back at my blog on Artnet from 10, 12 years ago. It was kind of like a diary. It seemed kind of like a waste of time, but really it was an investment in the future.

And I was saying to this young writer, “Why don’t you have a blog where you write once a day and post about what you saw or what you’re thinking about.”

But of course, when I was young, if someone said that to me, I would have thought, ‘I can’t do that. I don’t know what I think. I don’t know what to say.’

Now I’m old and I know what I think and I know what I want to say.

What I liked about Walter Robinson was that he was good at being dark. He would say things like, “We live in a world filled with resentment, racism, stupidity and hate. The consumerist utopia sells us on the idea that a better world is possible. All you need is a little dishonesty,” with a casual matter-of-factness that dared you to argue with him. For someone whose head was almost certainly a great aquarium swimming with art and the strategies of artifice, he also had that quality of obdurate journalistic loyalty to facts, reality, and truth.

He counterbalanced his grim outlook with a breezily playful and relentlessly deadpan sense of humor, so it was sometimes hard to tell when he was kidding or not—as when he “claimed as a figurative painter to have debuted in 1984 the first-ever painting of a nude flossing her teeth.” (Seriously, is this true? Where is it?)

His commitment to seeing things as he saw them and then saying out loud what he saw was inspirational, driven by sensitivity to the world rather than callousness. He seemed to recognize the necessity of seeing and thinking about the things that are hard to think about and see – and not just the things that are fun, sexy, and delicious (though much of all that made it into his repertoire too).

At zing, we join the art world in remembering Walter for his sense of humor, his insight, art, and words:

The Wallyburger

two-page spread from “Big & Beautiful”

In zing #23, curator Charlie Finch explained Walter’s paintings of fast food hamburgers, which he dubbed the Wallyburger, as so:

The Wallyburger becomes more excessive the more you examine its contents: drip equivalence achieves statis in the paint Robinson meticulously applies, the tomatoes rolling into cheese in the imagery and the automatic Pavlovian drool which ensues. Never underestimate the power of a burger, even a painted one. . .

The Fertility Painting

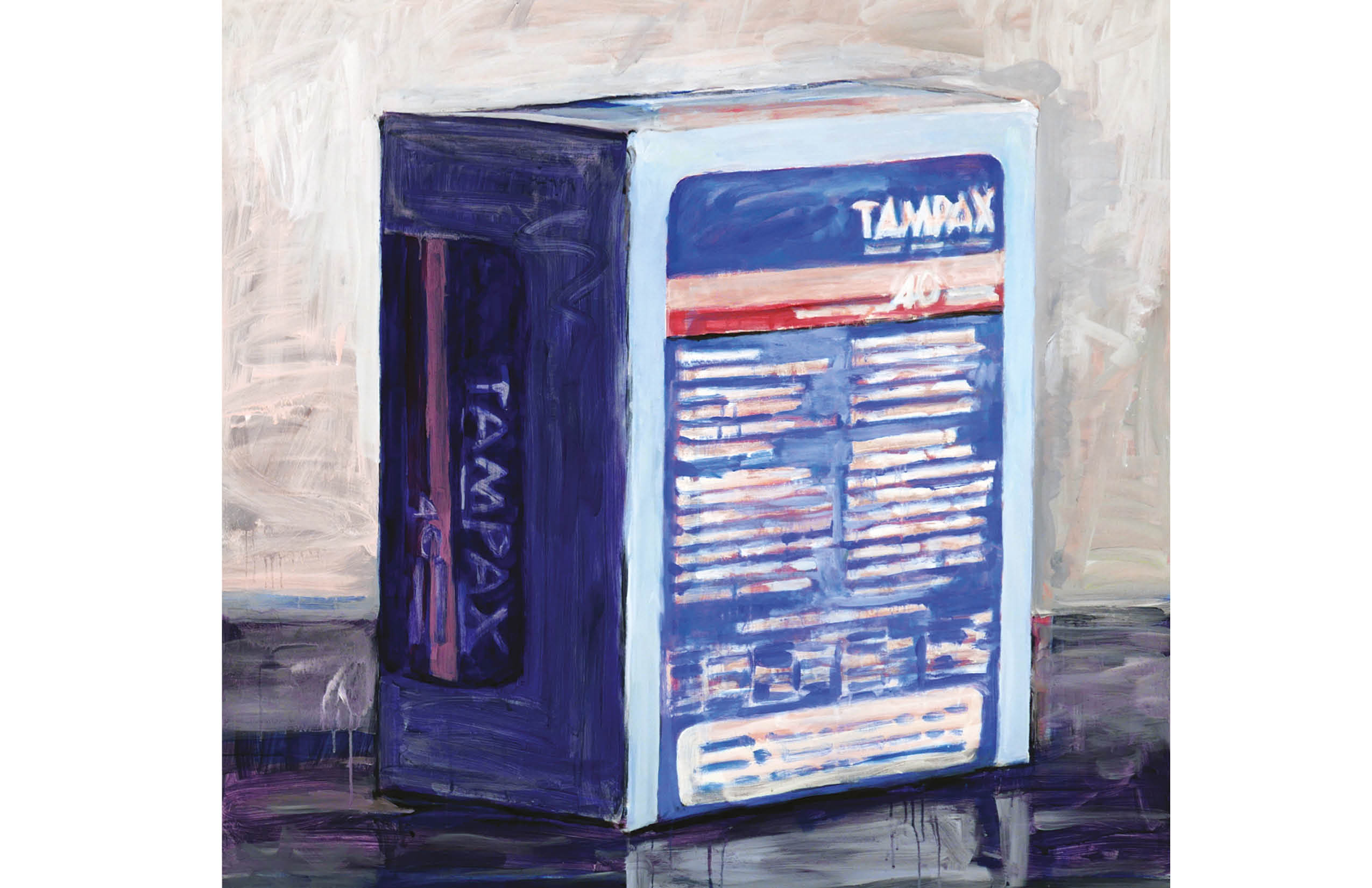

from Pharmaceuticals

Naturally, when Walter wrote his own curator’s note for a project of paintings he contributed to zing #25, it was a work of art unto itself, ending on this note:

The other works from that [Pharmaceuticals] show have found homes in important collections, thanks to Jeffrey Deitch, who included them in the survey of my work that he hosted at his gallery in October 2016. All save for the four-foot-square painting of a box of Tampax, that is. My ‘fertility painting’ I’m keeping for myself.

The Male Paintings

Oxford Dress Shirt Lands End, 2016, acrylic on paper, 12 x 9 in

When, in an interview for zingchat, Devon Dikeou asked Walter why he was painting so many shirts, he gave this as an explanation:

I paint a lot of sexy girls, in the studio I’m surrounded by images of women—you know, no one is really interested in men as a subject, not men OR women. But I felt bad, I don’t want to seem a complete dog, so I needed a masculine line, for balance.

So the thing about the shirt paintings, is that they’re MEN’S shirts, so they’re male paintings. What’s more, the images come right from the catalogues, or more typically from advertising emails, and the shirts are all flattened, folded and squared off. They’re pinned down, baby, can’t move at all. They’re just torsos, figurally castrated!

Not some kind of visionary

When I interviewed Walter in 2013, I foolishly prodded him, trying to get him to take a stance on real art vs commercialism or something silly along those lines, and instead he gave me this:

Early on I was interested in the idea of being straightforward and not pretending you’re some kind of visionary or something. It’s stupid. That’s my story and I’m sticking to it.

Lessons of New York is a collection of oral histories from the LES art scene of the 70s and 80s. This never before published interview was conducted November 2014 in NY, NY.

Diagram: “tag”, “throw-up”, and “piece” by Al Diaz

Amidst the dirty-glamour of the downtown art scene of the 70s and 80s, artist Al Diaz (b. 1959) formed the pen name SAMO with his classmate Jean-Michel Basquiat. Then a couple of unknown kids at City-As-School High School, the duo tagged the dilapidated streets with smart-ass poetry such as, “SAMO© 4 THE SO-CALLED AVANT-GARDE” and “SAMO© AS AN END TO BOOSH-WAH.” Their friendship would prove, like so many of Basquiat’s relationships, to be fiery and generative, driven by both fraternity and competition.

Interview and editing by Rachel Dalamangas

We were real cynical and rebellious kind of kids. Fuck everything kind of thing. Jean [-Michel Basquiat] felt that way. I felt that way. We were dissatisfied.

The 60s didn’t seem to accomplish anything. The sexual revolution. We were jaded. It was pre-AIDS so everyone was screwing around. We were just kind of a bored bunch. We rolled our eyes a lot. We didn’t have faith in much. The city was dilapidated. It was a time of mild hopelessness. And you’re at the age where you think grownups are a bunch of liars and everything is a lie.

We didn’t really believe in anything. Our lack of belief in anything was an alternative to belief in anything else.

We didn’t make “street art”. It was graffiti. The “street art” thing is a little more academic. You go out there with the intention of making art. Graffiti, in my generation, we weren’t trying to make art. I was trying to get my name around. I wanted to be famous.

Some people will do anything to get themselves noticed. Jean was like that. One time, when we were in high school, maybe the summer after, he painted his face silver and stood on the Brooklyn Bridge so people would look at him. He would take his overalls and cut a piece off so that you could see his crotch, exposing himself. Anything he could do to get someone to look at him.

When we started doing SAMO, it was almost competitive but a collaborative kind of thing. We wanted to keep the same handwriting. We had rules about it. We would practice it. We would look at stuff and write stuff together and try to keep the best stuff. We were editing ourselves. Both of us were lovers of language so we’d try to out-clever each other.

Yeah, we wanted SAMO to look slick and cool if that was so much high art but it was all about style and ego. Driven by that. The bottom line. Then it developed into making it look prettier and this and that. That was a gradual process. It didn’t start out as, “Hey, we’re making art here.” Nobody ever said that. Nobody ever said it was going to be a global phenomenon.

We also didn’t say it like, “We’re going out tagging.” We were paintin’. We were bombin’. And we’d tag something. The i-n-g of it didn’t come until later, if that make sense.

SAMO was only me and Jean though. People would try to copy it, but it was only us. We were a little bit Nazi about it. We were possessive.

It was crazy. It was a fun time. It was a hedonistic lifestyle.

I remember one time, I was at Tier 3 and they had just changed the policy. They had just started hiring some bouncer type door people because before everyone would just walk right in. And Klaus Nomi was standing in front of me waiting to get in.

When he gets up there, the guy says, “Alright, $10.” Like a big gnarly dude. Probably a Hell’s Angel.

And Klaus goes, “You don’t know who I am?”

The bouncer goes, “I couldn’t give a fuck who you are. Give me $10.”

It was so fucking hilarious because he was so incensed and the guy couldn’t give a fuck.

I didn’t really know Klaus at all though. He was just around with all those other people.

I was very salt of the earth. I didn’t have crazy hair. I wasn’t trying to be fabulous. People like that kind of intimidated me. Jean was very good at that, looking like completely insane. But I was from the Lower East Side, working class kid. I really wasn’t trying to do any kind of like expression with my clothing.

I screwed around with some of the girls that were all costumed out and stuff like that, but I was kind of very street. That kind of set me a little bit apart.

I knew Keith [Haring]. I thought he was a very smart guy. Very ambitious and very focused on what he was doing, but he could be a little catty. I remember one time he said, “Al Diaz is a dabbler” and he didn’t even know my history.

He just said some bullshit. Because I was no longer doing SAMO? Because Jean was saying something about me to him? Jean was saying some nasty stuff about me for a while until somehow we became friends again.

After ’78 until at least 1980 we went our separate ways.

When he took the SAMO, because it got some media attention, he was using it as a springboard for his career. It was no longer SAMO. It was Jean.

We had gotten that article in the Voice recognizing us so he just rode that but I had nothing to with that. I had been as much a creator of it as him so I had some resentment about it.

After the SAMO article in Voice we dropped off. It was over some stupid shit. We had this place where we worked for this guy. A white metal casting shop on Spring Street. He would work there anytime he ever needed a few dollars.

So one day we were in the shop and we found this figure of a Buck Rogers. Remember those little green plastic soldiers? It was kind of like that, but it was Buck Rogers holding a ray gun with a helmet.

He said, “Wouldn’t this make a cool pin.” Kind of a brooch.

So I was like, “Yeah, yeah, that’d be cool.”

Then he vanished for a while and I ended up making the pin because I was making pins and selling them. I had my little industry going.

When he found out I was making the Buck Rogers pin he flipped out. He was so incensed and that was it. It was over some stupid shit like that.

It broke my heart. He had like zero skills for dealing with conflict.

He was an amazing human being because his head was in all these places. You’d never see him reading so it’d be like, “Where’s he getting all this information?”

Nobody really thought we were gonna be famous. Well, Jean did. Jean knew he was going to be famous. I’m sure Keith did too.

The night we hooked up again, he told me that. I hadn’t seen him in like two years and he told me he was working on that film Downtown 81 and then we tripped that night.

We tripped that night and walked around the West Village and we kept finding joints, like four joints, like someone had dropped them like one by one. We were spouting, babbling, and one point, we were sitting in Sheridan Square, and he turns to me and he says, “Al, I know I’m going to be real famous and I’m going to die young.”

What do you say to that, right?

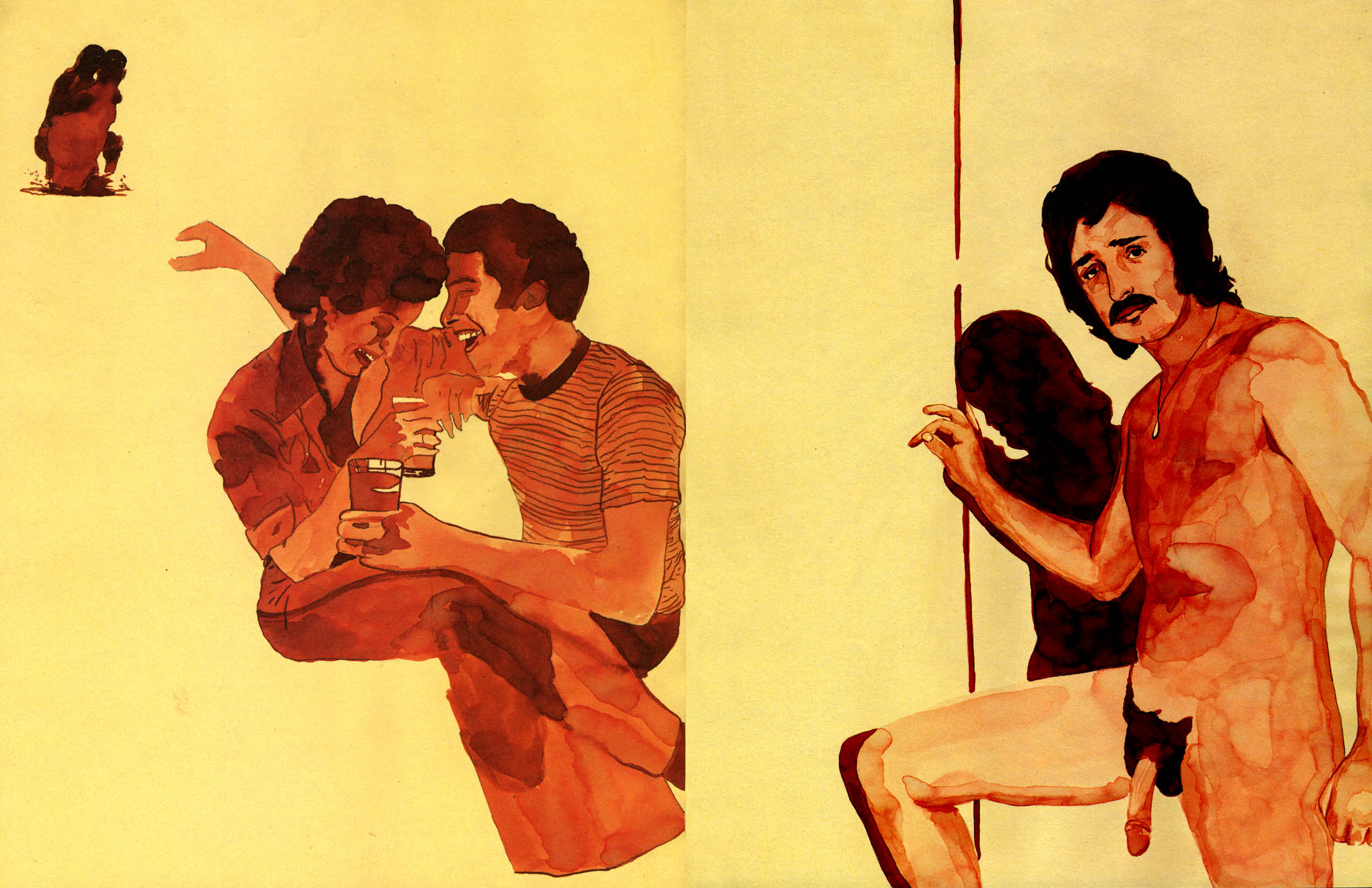

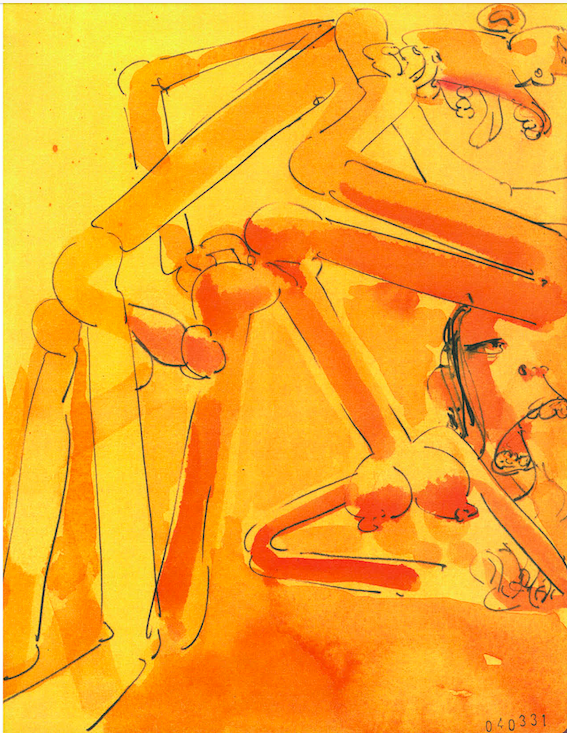

One of the first things I judge about sexually explicit art is whether it is at all gross. Maybe only a little. But maybe a lot! Good art about sex requires bodily fluids, subverted gender roles, kink, something weird and/or icky.

The second thing that goes a long way with me in love and art is a good joke. A sense of humor is highly rated by both men and women as a seductive quality, and moreover, making someone laugh is arguably more difficult to do than making someone cry – and is just as revealing as what turns someone on.

Finally, what I like about the aesthetic of these projects in particular is their distinctly Gen X flavor of grungy, too-cool, low-key ragey femininity – both in gaze and object – that is celebrated as sexy.

One time when I was giving a tour at the Dikeou Collection to a college class, a young woman burst out laughing when we got to the Tracy Nakayama exhibit and pointed at the flaccid penis of a naked man on foot leading an enormous horse. Nakayama’s paintings sourced from vintage porn often provoked this kind of delighted, giggly reaction from young women who visited the Dikeou Collection, and that is one of the best things there is about the work of Tracy Nakayama.

One time when I was giving a tour at the Dikeou Collection to a college class, a young woman burst out laughing when we got to the Tracy Nakayama exhibit and pointed at the flaccid penis of a naked man on foot leading an enormous horse. Nakayama’s paintings sourced from vintage porn often provoked this kind of delighted, giggly reaction from young women who visited the Dikeou Collection, and that is one of the best things there is about the work of Tracy Nakayama.

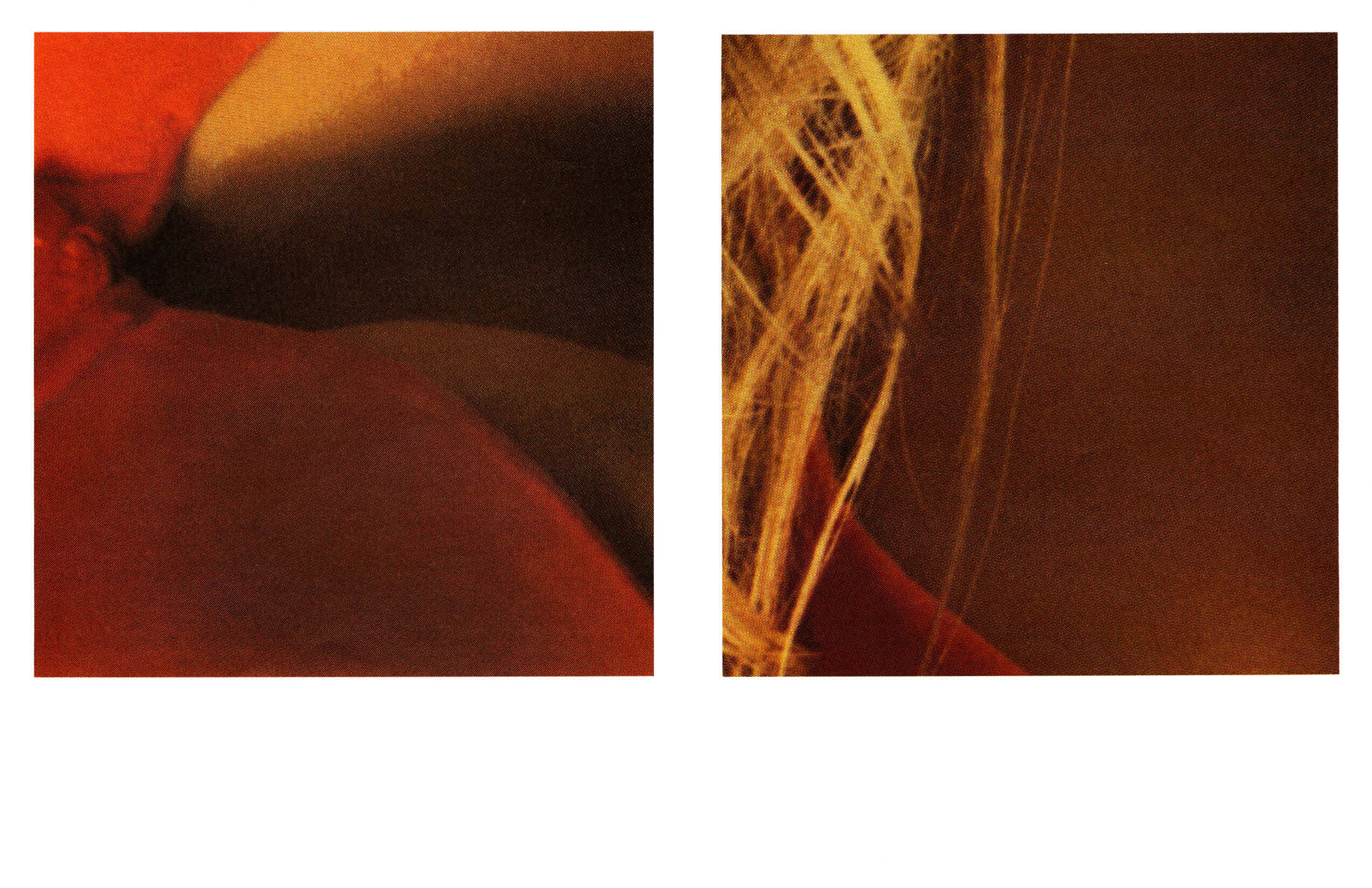

No stranger to the subject of erotica, gallerist Mark Sink curated this series of close-cropped detail images from a Victoria’s Secret ad by artist David Brady. Instead of an entire woman in her underwear, there’s an eyebrow, the divot of a throat, silky blonde hair, fruit-like cleavage in a bright pink bra. The hyper-close framing makes the images feel more intimate and even erotic though less explicitly sexual than the source material.

Why is that rabbit performing oral sex on that woman?

Why is the other rabbit watching?

Why are they smoking?

I don’t know! I don’t care!

Because it’s so effortlessly cool – bizarrely sexy, even – and would look great on a t-shirt or a tote.

In this project, the female form appears in strip clubs and abandoned places as a broken doll or partially completed graffiti, proving that even the creepiest alley can instantly become creepier – but also sexier – with the addition of the naked female form. In her curator’s note, Kereszi writes, “I noticed all the abused, tortured and mutilated, sexy female mannequins in the various haunts I visited. I’m not sure what I’m trying to say here about sex and violence and horror and voyeurism.”

In Cronin’s art historical resurrection of the sculptor Harriet Hosmer, I learned many things. For example, one dead guy whose name doesn’t matter that much criticized Hosmer for “casts of the entire female model made and exhibited in a shockingly indecent manner” – which sounds pretty hot. And he wasn’t wrong of Hosmer, given the undeniable sensuality of the subject at hand, her masterpiece of female-on-female gaze, Zenobia in Chains.

When I think about defining the difference between pornography and art, two quotes come to mind:

When the Honorable Supreme Court Justice Stewart Potter famously said of pornography, “I know it when I see it.”

And when 2010s YouTube personality Hennessy Youngman said that the litmus test of any work of contemporary art is if it, “doesn’t serve an actual function in society.”

Obscene for the sake of considering the obscene, Gomez’s paintings are lyrical and crude, somehow satisfying the conditions of both.

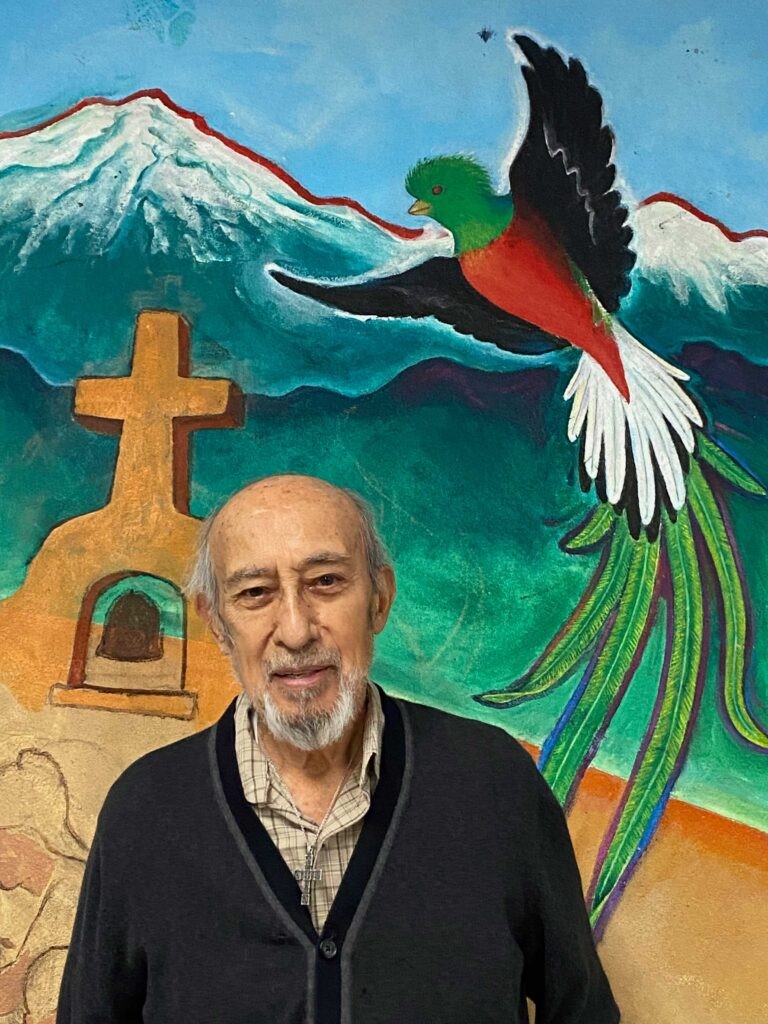

Leo Tanguma (b. 1941) is a Chicano muralist known for his works that integrate Mexican American heritage, spirituality, social justice and autobiographical elements. Born in Beeville, Texas, he began his career in Houston with ambitious murals that advocated for social change. In the 1980s, he moved to Denver, where his public works made waves in the Denver International Airport, and he continues to create murals throughout the Denver community, most recently at Ricardo Flores Magon Academy. This is the second interview with Leo Tanguma to appear on zingmagazine.com, the first was conducted by Rachel Dalamangas and can be read here. Leo will be featured on the ARTiculated: Dispatches from the Archives of American Art podcast, produced by Archives of American Art | Smithsonian Institute oral historian Ben Gillespie.

Interview by Ben Gillespie and Josh T. Franco

You’re coming up on nearly 40 years in Denver—how has your understanding of the Denver community changed in that time? What excites you now in Colorado?

When I moved to Denver in late 1983, the Denver community, especially the Chicano community, was experiencing a severe problem of gang violence. After attending meetings which sought to address the problem, I observed the actions already taking place in dealing with the gangs I was deeply impressed with what I saw. I immediately added my contribution to those efforts by constructing a movable, sculptural mural on gang violence. I designed this mural to be shown in one area, dismantled, and then taken to be shown at another site in order to reach as many viewers as possible. My understanding of the issue developed into an admiration for the city and for the Chicano community in particular.

During the past 40 years, Denver has only increased its kindness towards me. This situation has remained constant as I have seen my work welcomed despite its frequent political or radical content. For example, the following are some of my most political murals:

Beyond This Cross (1986): This was a sculptural mural in the shape of a cross, 33 feet in height by 45 feet at the base, and was exhibited for an extended period at the Denver Center for the Performing Arts in downtown Denver. The painted imagery on the cross was a condemnation of the United States Government’s support for Central American dictators who oppressed and murdered many people using the military as well as death squads.

The Torch of Quetzalcoatl (1989-1990): A sculptural mural 72 feet along a curved base by 12 feet in height tapering down on its ends to 2 feet. This mural was commissioned by the Denver Art Museum in 1989-1990. Its subject was the Chicano Movement and Movement for Civil Rights in the United States.

In Peace and Harmony with Nature and The Children of the World Dream of Peace at Denver International Airport (1993–1995). I painted two sets of large murals with a total square footage of 692 square feet: I was assisted by my daughter Leticia Tanguma as well as a few other Denver artists.

Given Denver’s openness to progressive artwork, I wonder why more Denver artists, especially mural painters, in the Denver area have not seen fit to examine social and cultural issues in paintings and offer them up for the public to enjoy or scrutinize? I call Denver’s stature one of down-to-earth sophistication with tough demands but with high rewards for those who try.

Leo Tanguma, The Torch of Quetzalcoatl, 1989-1990

You’ve described human dignity as a foundational impulse for your work, how would you define it? How have collaborators defined it or changed your definition of it?

My sense of human dignity comes from religious Christian ideals instilled in me by my farmworker parents during my youth. The murder by the Sheriff of my mother’s two cousins at their ranchito in my hometown south of San Antonio, Texas inspired my rebellion against authority. I realized that the social order and its authority over us demeaned, and it often destroyed, our human dignity. What the Sheriff did that day was to attack our self-respect, that is our human dignity, especially since we could do nothing about it. The Sheriff was exonerated in this case as he was in other cases that involved his killing of other Mexican-Americans.

Following the murder of my mother’s cousins, our local community resumed its life, and we were soon back “normal” again: Happy in our homes and our barrio. Later I saw this return to normalcy as our reclaiming our human dignity.

As I matured, I painted mural depicting the struggles of all oppressed people fighting for a better life and thereby for their human dignity. I became aware of the Christian philosophy of Liberation Theology that stressed that Christians must have a preference for the poor and the oppressed. In essence I have been doing this all my life as a mural painter. I am not sure that my example has inspired other artists. Although I have spoken and advocated for an art reflecting not only our community’s culture but also its political struggle.

Leo Tanguma, Beyond The Cross (Detail), 1986

How do nature and the natural world factor into your murals?

I have shown nature in some of my murals. I equate beauty and fragility of nature as something spiritual, something that touches our senses with awe at the spectacular beauty of this mystical creation all around us.

Leo Tanguma, Leticia Tanguma, Cheryl Detwiler, In Peace and Harmony with Nature, 1993-1995, Denver International Airport

David Alfaro Siqueiros and Dr. John Biggers were major influences for your approach to mural making and meaning—how do you hope to influence artists today and tomorrow?

Dr. John Biggers, Professor of Art at Texas Southern University, stated that the greatest experience we can conceive of is the human struggle through the ages. He said, “Our struggle for Civil Rights is part of that monumental struggle for human dignity of which we are a part of.”

David Alfaro Siqueiros told me in an interview with him in his Cuernavaca studio that we Chicanos should not only paint the folkloric and cultural identity of our community, but also the political and social struggle. Siqueiros also referred to leaders and revolutionaries of whom we were aware. He also pointed out unknown and forgotten martyrs and heroes in the human struggles of the past.

At my age I can only say that hopefully my example alone could be of some value.

Looking back on your long career in art and activism, what does “Chicano Art” mean to you today?

Chicano Art means to me the representation of my community’s aspirations for liberation through the mediums of artistic creation. However, the artform which most lends itself to that expression is mural painting.

I have often said that mural painting is our Mexican heritage going back two thousand years B.C. in ancient Mesoamerica. I am not sure about the following being applicable to our Chicano Art, but I suggest that the cave paintings of Altamira, Spain, should be incorporated into our Chicano sense of history.

Leo Tanguma, Leticia Tanguma, Cheryl Detwiler, The Children of the World Dream of Peace (Detail), 1993-1995, Denver International Airport

You often collaborate with young people. What do you hope they take from the experience of creating murals with you?

In most, if not all, of my painting with youth, I use the symbolism or figures which we may be painting in a mural as messages about their intrinsic worth. Often in developing a mural topic to be painted with youth, I point out the importance of what we are about to do. Instilling this mindset at the beginning, our planning inspires those youths to more meaningful ideas for a mural. I suggest that while painting a mural is a fun experience, it can also tell a story or message with their pictures in a mural.

On more than one occasion, I have been approached by middle-aged persons who have said to me “Do you remember me? I painted with you in Arvada Middle School?” Or many other locations where I painted with youth. A particularly memorable experience was when someone said, “Remember me? I painted with you at Platte Valley!” (Platte Valley Youth Services Center, a youth correctional facility). He added “And you talked to me!”

Everyday heroes from many cultures come together in your murals—who or what is a symbol of heroism for you today?

I am inspired by many revolutionaries of the past. But my heroes are my parents, a friend in our barrios of many years ago, and the following very special people:

My sister Enedina who was raped and had a child but continued to work in the fields to help support our family.

My Uncle, Pedro Jarro, who fought in battle in France in World War I.

Dr. John Biggers, my African-American professor at Texas Southern University, who advised me and encouraged me to continue painting murals on the street.

But most of all my wife Jean, who endured more than ten years of domestic abuse from her partner before she met me. She, nonetheless, fought for social justice for others starting in college and has continued in the struggle to the present day. Since I met her over 40 years ago, she guides and inspires my work. Her progressive ideas have greatly influenced me. Beyond that is the person who she is: her ability to love deeply and never expect anything in return. Her love for the oppressed, especially those in our American society who struggle daily for a better life. Her patience and smile always move me, and I thank God for such a love in my life.