Rainer Ganahl is a conceptual artist and lover of Marxist theory, who works in mediums ranging from film to political Manifesto. He often records and makes objects of events like educational seminars, Marxist fashion shows and imitation of the life of writer Alfred Jarry. Simultaneously student and teacher, his work portrays the intersections of politics, education, language, class, history and fashion. His artistic practice is never solitary, but rather relies on collaboration and group involvement to draw connections between audience and performer, brand and consumer. Ganahl has published numerous books including Reading Karl Marx, Ortssprache—Local Language, Educational Complex, and Please, Write Your Opinions of U.S. Politics. His work has been featured in zingmagazine five times including Basic Russian (Issue 2), seminars/lectures (s/l) (Issue 15), Iraq Dialogs (Issue 19), and FONTANAGANAHL—Concept of Rage: 1960s/2010s (Issue 23). I spoke with him about his project Hermes-Marx, which is featured in Issue 24 and resides at Dikeou Pop-Up: Colfax in Denver, Colorado. In our correspondence via email, Ganahl exclaimed “MY ENGLISH SUCKS”, which really isn’t true: Rainer Ganahl writes with an elegant fire.

Interview by Liana Woodward

How did you first become interested in the works of Karl Marx?

As a teenager I came across Karl Marx’s early writings published in German in a beautiful light blue hardcover volume that was handy and lovely. His thinking changed my life thought. His writing has little to do with what he [eventually] came to signify, but rather with historical materialism as a philosophical position in regard to religion, to society, and to work.

How can we understand the art world, and the creation of art objects, through a lens of historical materialism? Where does Marx’s political philosophy intersect with art?

The short and cynical, but truth-carrying answer would be a classical one: follow the money. A more melodic or pastoral one could be: go with the pleasures and anxieties of people. The drives and truth-techniques that they develop to domesticate, cultivate, or differentiate their senses and what-have-yous. People are creatures who create and depend on tools to handle their imaginings, ghosts, fire and fears, to fight off enemies, hunger and cold, to produce pleasure and excess, fun and abundance, to fill in the gaps between misery and disease, shortage and lack.

I tell my kids that stories are made by women and men, not by some god. Ghosts and gods are nothing but stories we use to deal with fears and desires of bad and good monsters, beauty and fairies, power and its opposite, gain and abundance. In the realm of storytelling and demonstrative silence (organized noise or haptic enjoyment for the ears and eyes) we approach what later will be commodified as art.

That is Marx for pre-K and kindergarten and can produce satisfaction and arguments until graduation with curators and wealth managers, portfolio geeks, and speculators. Hence, Marx for red points and red tapes, for high heels, private jets and Basel or Hong Kong free-port storage access. Marx is really the pre-inventor of the Swiss Army Knife for philosophy and polyglot money. Viva Marx.

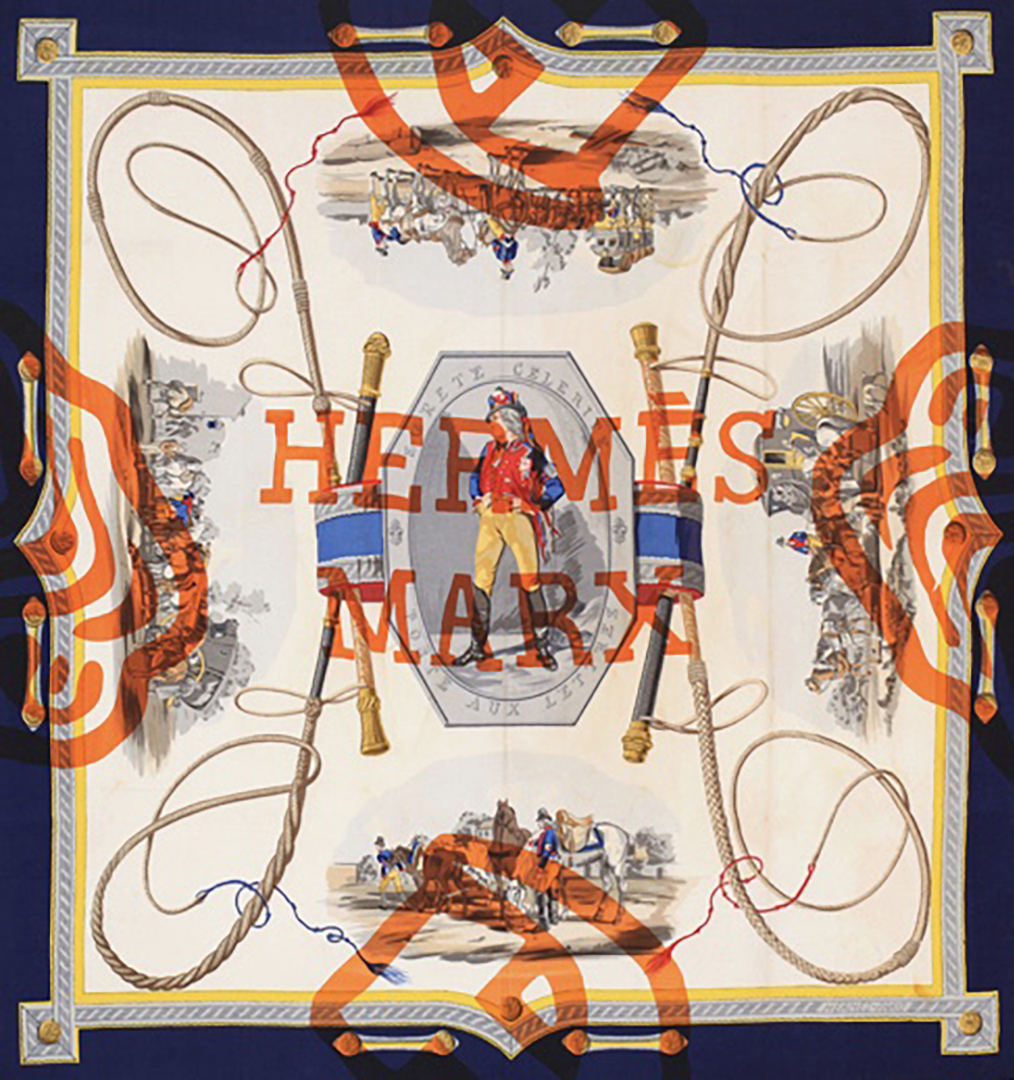

Speaking of money, can you talk a bit about how your project Hermes Marx? By silk-screening your own Marxist imagery onto the scarves you are in some way destroying their value as high-end exchange commodities. Is there some intrinsic or artistic value that you add to the scarves?

Well, as an artist I have to assign artistic value to my art works. If I don’t do it nobody else does. So yes, I do assign my ‘destruction’ or my ‘intervention’ a precondition to render a consumer object into my art. I acknowledge that the classical exchange value of the Hermes scarf is wasted with my design silk-screened over the original foulard but by doing so, I defend it as my proposed art work.

How do you think the magazine format changes how Hermes Marx is perceived by the viewer? Do you think the image of the object holds the same power or value that the actual object does?

No, it is not the same at all—but some art works photograph better than others and therefor what you see is not what you get—it’s either better or worse but both legitimate.

The scarves that you used for Hermes Marx have designs related to colonialism. How do the symbols and words you silk screened onto the scarves interact with that imagery?

There are two words I don’t change: HERMES MARX in reference to the corporate reference of the French foulard Hermes Paris. I consider the name Marx to signify an attempt to envision, demand, claim, enact, and fight for a larger more even kind of justice that is not only defined and reserved for the powerful and privileged. So all I did was exchange PARIS, the capital of the 19th century and French-speaking colonialism, with the name of a German philosopher who presented the world with the most radical ideas of justice of his time. Let me also point out that Marxism came with the symbol of the overlay of a hammer and sickle and the fist which is a part of the design that I print over the original French silk scarves.

Is there something in particular about Hermes Paris as a company that made you want to use their products for this project? Why not some other well-known designer?

Hermes belongs to one of the most prestigious fashion and accessory houses. They are know for making everything themselves including the production of silk and the colors that enter the product. It is truly beautiful and not necessarily cheap which makes if more coveted and impermeable to sales and other price dumping. Somehow they seemed to anachronistic even in the way they run their family biz and I think the company is still largely controlled by the family. I myself collect these foulards and truly love them.

Lucie Fontaine is the type of person who will set up camp in your home and redecorate it with works collected from her very talented friends from every corner of the globe. She’s also the type of person that will use that residency as a jumping off point to pursue new projects and explore new possibilities, like the work she did for issue #24 of zingmagazine. She is, in other words, the best houseguest you could possibly ask for, the type that has something to offer and doesn’t offer it begrudgingly. In the excerpted interview included here, we discuss her work for zingmagazine, get a look at what makes her tick, and learn more about her process. She’s never asked to live with us, but if she did, we wouldn’t charge her rent. In fact, we would put her on an allowance, provide a daily turn-down service and source the finest fruits from around the world to put in a bowl on her dresser. Why, you ask. Because she deserves it. That’s why.

Interview by Oliver Nevin

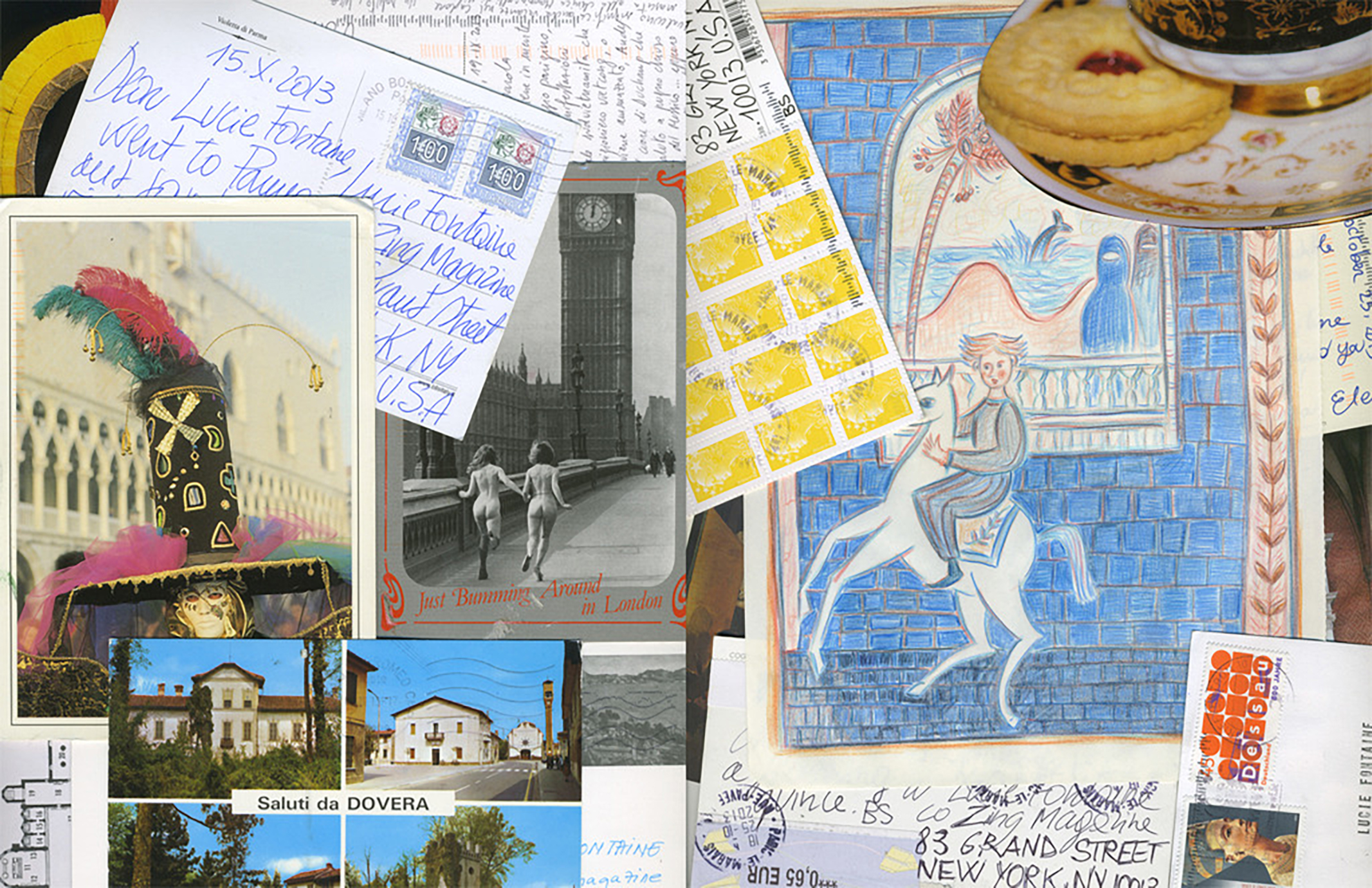

Can you tell me what got you interested in postcards? Not that a postcard can’t be beautiful and well designed, but they are often quite mundane and painfully ubiquitous.

The starting point of the project was a show that I did in Summer 2013, in Paris, at Galerie Perrotin. I wanted to ask, what is a souvenir? Imagine when you travel, and you want to buy an object that somehow represents your experience, but it’s never real and authentic. The New York gadget that a tourist buys is something that a real New Yorker would never actually use. Or you encounter the paradox where you go to Venice and you get the real, authentic, miniature gondola and then you discover it was made in China. It’s like the souvenir becomes the tourist. It’s all about the idea of what is authenticity and what is identity and how does a souvenir interact with all of those ideas.

But this project is obviously different the one that you did at Perrotin. Can you explain the leap from that original idea?

That show featured about 20 artists, and then I wanted to add a new chapter to the show by asking all the artists who participated in the project, plus a couple more people, to actually write postcards to me at the zingmagazine office.

You really wanted to dive deeper into that idea of giving life to an experience, and looking at all of the different things that make up that experience and how the many facets of our life are related to it?

The point of the souvenir is also that it’s not so important when you are there. But it becomes important the moment you get back home. And then of course it’s also associated with the idea of kitsch, but it’s part of the different meanings of what a souvenir is. All of a sudden, we were receiving postcards that were pictures of Paris, but they were sent from California, or they were anonymous, or they had been redesigned and altered by my friends, so we were able to add a layer of fictionality to this narrative of souvenir.

How many did you get?

I think around 40. I want to do a show with all of the postcards but I haven’t done that yet, because the postcard is something that you show in the house, and this idea of something intimate and domestic, especially domesticity, is very important for Lucie Fontaine.

I don’t think I’ve ever heard a creative proclaim to strive for domesticity. Why domesticity?

It’s something that has been a part of me from the beginning. I wanted to show works in a way that was not the usual setting. The first location of the Lucie Fontaine project space in Milan was actually an old and crappy barber store, where I never changed the floor or the walls and the atmosphere of the space remained the same. I was showing the works of young artists in this outmoded atmosphere, but it felt very intimate and domestic. The other two locations in Milan were also domestic spaces. And the Lucie Fontaine Space in Tokyo was inside a traditional Japanese house. There are also plans for a domestic Lucie Fontaine space in Tel Aviv too.

So you have a real commitment to the domestic? To be simple and raw instead of polished?

Yes, but it’s also about playing with the rules of the game and blurring boundaries between different roles in the art world. Another time that domesticity played an important role was during the show Estate I did at Marianne Boesky’s gallery uptown in summer 2012. The space was a beautiful townhouse on the Upper East Side. My three employees were living inside the gallery and transformed it back into a proper home. I decorated each room with the things that you would normally find in a house there, including antique furniture. But they were also artworks and complied with the themes of the show. You would enter a bedroom and you could see the wallpaper and flowers. But the wallpaper was a work, and the flowers were a work and the chair was a work, but it was very subtle. And then I had friends sending pictures and postcards that were helping to build the narrative of fiction in the show. So that’s another way that the postcard was something familiar.

I suppose that was like reaching the pinnacle of domesticity. Your artwork was quite literally in the home?

Indeed, and it was great. The first month my employees were installing the show, so the gallery was closed. When the show opened, they decided to stay and live there while the show was open to the public. So for two months, and especially in the second month, they were waking up each morning to tidy up their rooms before 10am, because visitors were coming in to visit the exhibition.

I guess it’s interesting to me to get a look at how a project like this starts as this sort of inkling, or seed of an idea, and ends up growing into something real and tangible.

The first time I started handling postcards was while I was living in the Marianne Boesky gallery/home. It wasn’t really until after the show in Paris, which was about tourism and travel, that I realized I should do an entire project built around them, but the seed was planted while living in that gallery.

That’s quite fortuitous.

It was there that I first received some postcards from some friends, and my employees had them displayed in the entrance where there was a big mirror. Because they were all actually received at that address, I was keeping a part of the fiction of the space intact, which was fun.

But you didn’t have to fake domesticity. Domesticity quite literally refers to matters of and/or relating to the home. It doesn’t feel very fictional to me.

I didn’t have to fake it, just preserve it. I remember there was one artist friend, he came to visit the show one Saturday afternoon, and he said that when he first entered he thought he was in the wrong place. He said, “Oh shit, this is wrong, I just broke into someone’s home.” After he left and double-checked the address, he realized that was actually the right place. That’s exactly what I wanted.

Do you feel like you were able to stay true to your commitment to authenticity with the project in zingmagazine?

I do. I think it’s all about the idea of what is authenticity and what is identity and how does a souvenir play with and interact with those notions. So at the show in Paris, I wanted to install it as a bazaar. I didn’t want it to look standard, like a white cube installing, but more like overabundance, and to develop a much denser dialogue with the pieces. I think the way those postcards were assembled in the magazine really ended up staying true to that idea. When you turn the pages, you are in the postcards, surrounded by them, and I think that gives the reader a sense of being surrounded by the experience and significance of each postcard.

Well I’m glad you were able to achieve your vision for this project. Thanks so much for taking the time, I enjoyed the conversation.

You’re welcome, it was my pleasure.

Jeff Rian is a writer and musician, an associate editor of Purple Fashion magazine, and a professor at L’Ecole Nationale Superieur d’Arts Cergy-Paris. He has written numerous essays and exhibition catalogs as well as a regular contributor to Artforum, Purple Fashion and The Purple Journal. He is the author of The Buckshot Lexicon and Purple Years, and has written monographs on artists, Richard Prince, Lewis Baltz, Philip-Lorca di Corcia, and Stéphane Dafflon. His CDs include Everglade, with Jean-Jacques Palix, and Fanfares and 8 de pique for Alexandra Roos, and Battle Songs, with his group, Rowboat. Jeff’s most recent CD project, Météo, was released as part of zing #24. The project was curated by photographer and past zingmagazine contributor Giasco Bertoli, featuring three instrumentals and four songs written with Gérard Duguet Grasser, and recorded with Bob Coke. The music itself is minimal, with fingerpicked guitar that ranges from bluesy and percussive to wobbly and romantic, accompanied by crooning vocals, and the odd tambourine. Well-crafted atmospheric music that sticks with you. Here we shed light on Jeff’s “secret” life as a sideman.

Interview by Brandon Johnson

In contemporary art circles you are most widely known as a critic. Can you tell us how you originally got involved with music and the trajectory of that path since then?

At around age ten, guitarist James Burton, sideman in Ricky Nelson’s band on the long-running television show, “The Adventures of Ozzie and Harriet,” struck me as a model. I wanted to be a sideman. My father bought me a Silvertone acoustic guitar at Sears, for $17, and a book of folk songs. I discovered I could play many of the songs almost immediately. Within a month I was in a folk trio. I was 12. My voice hadn’t change. But the two other boys I played, their voices had changed. So I was the girl voice. We played at parties, at the pool we belonged to, at school, and wherever else we could. By the time I was 15 the band had gone electric. My interests were now the Stones, Hendrix, Led Zeppelin, Jeff Beck, Cream, and a group called The Band. By the time I was 18 or 19 I was the lead guitarist in a club band in Washington, D.C., a town with excellent guitarists. Playing nightly and hanging out with musicians was excellent on-the-job training. This was before disco, when live music paid real wages. Around then my worried parents sent me to take battery of aptitude tests. The tester told me to forget everything other than music, literature, and art. “Art?” I wondered. I’d flunked art classes. I knew nothing about art. I’d been to the Smithsonian Institute twice, once with my parents and once with a friend, when we were 14. He was actually interested in art. After taking those tests, it occurred to me that art would be something to study and to satisfy my parents, and might be easier and allow me to play at night and come to school late. I enrolled in the summer session at The Corcoran School of Art (which didn’t require a portfolio). In my first drawing class there were ten girls, a Marine Corps colonel, a kind of art stud named Angel, and the girliest guy I’d ever seen or met in my life—who was an excellent artist. We became friends, and I tried to copy his drawings, and not insult him when I didn’t want to hold hands. At the Corcoran I discovered an entire population I enjoyed being with. Nightclub musicians—whom I’ve played with off and on my entire life—can be insufferable if you’re interested in anything other than your ax and getting high. Artists connect to the world differently, materially and aesthetically. They too want to spend all of their time making and thinking about art. Musicians woodshed, which is what they call practicing their ax, which is very demanding. The materials and requirements of the two are very different.

I ended up at the University of Colorado, completely by accident—hitchhiking west with an old friend, with only a week off from my current playing. But ended up staying. I needed to get away, I guess. I spent several months working as the assistant to a pot dealer, got in-state tuition, and enrolled in the summer session at CU, majoring in art. In my first year there I auditioned for a band. That band transformed into a jazz group no sooner than I was hired. So I had to spend countless hours learning scales and modes and how to play them over complicated chord patterns. Through friends of the dealer, I got us gigs at a club that featured national acts—making me the bandleader. We opened for many acts, some of whom, like Weather Report, Chick Corea’s band Return to Forever, I was responsible for getting in that room. By now, studying painting, drawing, and art history, I took classes which required students to write papers—which, to my surprise, I discovered I could write the night before and get a good grade, whereas in any class in which the professor gave multiple-guess tests, I was not very good. One of my professors told me I could write. I didn’t believe him. But I was learning to think differently, and I think music helped me to understand art in the way that it is made.

Toward the end of my five years at CU, the rhythm section of my jazz band—me on guitar, plus the drummer and bass player—were hired for a little tour, playing covers. I’d played covers for years, so it was easy. We practiced for about an hour and a half, then winged it at the gigs. The first night in the hotel room, the keyboard player, Brad Morrow (also a very good guitarist; we switched on a few songs), opened his suitcase, and to my surprise it was full of books. In my musician talk—which I still can’t shake, to the point of calling my 12-year-old daughter, “Man”—I asked him: “Man, what’s in the bag?” “Ezra Pound,” he said, demurely. That was unexpected. I didn’t have any literary friends until I met Brad Morrow. We became friends then and there. (He’s now a novelist and was the founder and editor-in-chief of the literary magazine, Conjunctions.) But I’d also had it with musicians—the lifestyle and the drugs, well most of them. I took a job cleaning the engineering building at the CU (dirty floors, not bathroom, hours to read). I read in earnest. This was my last year. For years I’d been a fan of new journalist writer Tom Wolfe. Brad turned me on to literary critic Hugh Kenner. I liked their styles. My other close friend at CU Dike Blair, who’s now an excellent artist, was unquestionably the most convincing “art type” in the entire art department. Brad and Dike didn’t know each other and we all ended up in New York in the years to come. Those friendships shifted my interests toward art and writing, though I have continued to be a sideman.

For a number of years after graduation—eventually earning a Master’s degree in art history—I devoted my time to study and reading about art, though I would fit in time to practice, simply because music is my drug. It’s also a problem, which might not seem like one, because more than one interest divides you. Writing, which I came to very late, totally replaced the woodshedding needed to play at a higher level—though I’ve been lucky to have played with some very high-level players. Eventually I turned to songwriting, and working with female singers, first in New York and then in Paris, where I live now, where I’ve played on a number of records as guitarist and composer, also with some very good musicians, and improvised for films. So I continue to play, but I mostly record. And I still prefer the art world, where I’m known as a writer, which takes up a lot of my time. Yet I can’t stop playing.

There are musician-artists, but for the most part they are nothing like dedicated musicians. The worlds of music and visual art are very different in outlook, aesthetics, and way of life. I’m probably a better musician, but I’ve had a better life working in the art world.

Despite this fundamental difference you describe between the perspectives of music and visual arts, do you find visual art, or even specific works of art, have influenced the way you approach music on a stylistic or intellectual level? Or do you continue to consider them separately?

Interesting question. I can only offer a roundabout answer. The art world changed the way I started to think about playing music, and music influenced the way I think about art. But I didn’t realize that for quite a while.

In 1985, I was hired to work on an international exhibition in Vienna as a mitarbeiter, literally coworker, a kind of coordinator. It was the occasion of the newly renovated Vienna Secession. The show was called Wien Fluss: 1986, or Vienna Canal: 1986. The title referred to the Vienna canal, seen in the film The Third Man, so the show was about foreign connections and Viennese influence. There were no Austrian artists. I worked with Americans, Vito Acconci, Richard Tuttle, and Lawrence Weiner, and a French artist, Jean Luc Vilmouth, who recently died and is the person most responsible for my move to France. The artists in the show were supposed to do the work in Vienna. I asked the curator, Huber Winter, who has a gallery in Vienna, to invite Richard Prince to participate, which he did, happily. I felt the show needed a younger American. I’d first seen Richard’s works in maybe 1981—rephotographs of black and white ads, using Ektachrome slide film, so they had a slight tint. Maybe they were hands with watches or women looking in the same direction. I didn’t understand them at all. Dike knew Richard and gave me his number, so I visited him, and during that visit I discovered he collected first editions, mostly postwar American writers, in as good a condition as he could find. I too collected first editions, and he was the first non-literary-type book collector I’d ever met, my age, who had similar interests—though he had a pile of good copies of pulp fiction paperbacks. Richard had a mint copy of Flannery O’Connor’s Wise Blood. I had many books from the 1960s, including all of Walker Percy’s books—inscribed to me, including his first book, The Moviegoer, which Richard and I talked about. (I had to sell my books to survive when l started writing). I’d been collecting books since I met Brad Morrow, back in college, when I started reading more seriously and hanging out with literary types and going to second-hand bookshops, which were aplenty back then. I almost went into to business with Brad selling first editions. But he was better at that, and did that himself, before he started Conjunctions and writing novels. Anyway, all this related indirectly to music, which was most people’s background noise anyway. Brad also played classical guitar. Richard had been in a rock band. I’d played folk, rock, and jazz. During Richard’s visits to Vienna he and I constructed an interview—it was his idea. I came back to New York in December of 1986. Richard had given the interview to Hal Foster, then a senior editor at Art in America. They featured Richard on the cover of March 1987 issue. Our interview was the first article to feature Richard’s work in a major art magazine. Why me—an unknown—instead of a known critic? I don’t know. Ask Richard. But that’s when I started writing—first reviewing shows for Art in America, then moving on to other magazines. In the interview with Richard I brought up Marshall McLuhan and the role of electronics on sound and space and images. My idea, from the beginning, was to write about art from the perspective of touch, which I still do: how things are put together; what might influence choices of images or materials; how aesthetic issues echo the social or political environment; and how instinct and perception rule the process.

I’d given up on what was called theory in the early ’80s. Not my cup of tea. Through non-art-world friends in New York City I discovered Gregory Bateson, specifically his ideas about “patterns that connect” and logical types (the meal is a lower level of abstraction than the menu that describes it; the farther up the ladder of abstraction you go, from language and words into categories or logical types, the further away you are from the “meat” of experience). I was reading McLuhan and Walter Ong’s investigations into preliterate and print cultures and what Ong called the “secondary orality” of electronic culture—radio, cinema, and television; how advertising was contemporary folk art; and how touch and acoustics are proximity senses, a lower order of abstraction than seeing. We build a world on touch, cobbling things together, which sight, which is a distance sense, cleans up and labels in literary categories, which are very high levels of abstraction. Being a musician, and always trying to get inside music, I related to how things are built from touch. The electronic environment’s secondary orality reverts to forms of sound and touch in technologies that require the highest level of literacy bringing them to life. This, to me, was the origin of pop art—a process built from middle-class folk arts—cars, rock music, ads, etc.—from the ground up. I spent ages trying to write about art in terms that ran against literary models. It wasn’t easy. But I felt, and still do, that art is calibrated (Bateson’s word) from primary instincts. Music is very much like that, but so are things like cuisine, surfing, rock music, customizing cars. (I grew up around people who customized cars, which are extremely aesthetic, if kitschy art forms; I spent a year working as a parts man in a store called Big Ed’s Speed Shop—Robert Irwin tried to explain how hot rod cars are American folk art to an art critic from NYC, who wouldn’t have it.). Collecting is equally instinctive. Anyway, I took classes at the New School with Edmund Carpenter, who, with McLuhan, Eric Havelock, Northrop Frye, was instrumental in creating the Toronto theory of communications. McLuhan was Hugh Kenner and Walter Ong’s dissertation advisor. These were my influences. None of them, except McLuhan, were spoken about in the art world, and McLuhan wasn’t exactly an author many critics cited. They thought he was too flakey, not serious enough.

In 1988 I was asked to write an essay for Richard’s first retrospective at the Magasin, in Grenoble, and tried to write about his work in the context of electronic orality. I felt that Richard pieced together his art instinctively, based on pop art, and included his book collecting—which was a gathering of intellectual property. It was the mint dust jacket that raised the value of those first editions. Dust jackets were like album covers—artistic advertisement, very much like pop art. Richard has a masterful instinct for such connections. He played in bands, before the 1980s—when, in the art world, playing in a band was kind of taboo. But Richard could never have played in the bands I’d played in or that Brad had played in. I found that out in Vienna. Richard played me an incredible song, on my guitar—a blond Gibson 335 dot-marker, which I still have. I was very impressed. He had style but no developed skill.

Art and music were separate environments with different kinds of “sensory profiles,” to use a McLuhan/Carpenter term. They began to cross over when inexpensive home recording technology came along. Nevertheless, literary people, music people, and art people operated in different aesthetic universes, and still do. Rock music was easier for people to play and, for a while people like me who could play all the songs on the radio, made a living at it. But that was only the first step in learning to play an instrument. Folk musicians, before the sixties, were poorer than poets. Jazz musicians weren’t much better off. The success of rock music and rock festivals altered everyone’s aesthetic and sensory environment, because everyone was engaged in it. A poet like Ginsberg became visible because of his connections to Dylan and the Beatles. But writers and artists and musicians were different species. Artists didn’t suit up like drag queens or fey bikers or pirates to play on stages; they didn’t talk like musicians. Art isn’t noisy. Rock was naked. Art was nude. Musicians can’t make contemporary art. Literary types can’t either. Those differences began to blur, but only slightly with computers and home recording—and only in the 1990s with the computer technology.

I didn’t play in bands for maybe a dozen years, until the maybe the early 1990s, when my girlfriend’s coworker’s band’s guitar player got sick. I replaced him. Then we got a better band. Then I replaced the entire band. I started composing music for the singer’s lyrics—sometimes there were two female singers, which was amazing. I applied everything I learned from jazz and folk-style finger picking, separating bottom and top strings to get more dynamics. I didn’t know how to use pedals, and still don’t, so I let my fingers do that talking. It was really fun. We played the clubs.

By then I’d been writing for Flash Art and Purple. They didn’t have professional copyeditors, which allowed me to publish more and faster, but was probably a mistake because, I mean, writing is really easy for me, but I make incredible messes that need structure. Editing and rewriting are difficult in the extreme, making me wonder why I do it at all. Then, in 1995, I moved to Paris. I was working at Purple, where I had no choice but to listen to indie rock—Sonic Youth, Palace Brothers, Ween, Daniel Johnston, Cat Power, a band called Fuck, Nirvana—bands I would never have listened to earlier as I didn’t consider any of them good and all of it pop music, about style and attitude, which I didn’t care about. As a musician I wanted to listen to a good instrumentalist. But as a writer I listened differently. And after several months of immersion, I began to let go of the technique prejudice. At about that time a guy named Gerard Duguet Grasser called the magazine looking for a bass player. Elein Fleiss suggested me. I told him, and the singer he was writing lyrics for, Alexandra Roos, that I was a guitar player. That didn’t bother them. My audition consisted of playing the guitar and then being presented with some of his lyrics—my French wasn’t good at all, but I had music for two songs almost instantly. It was easy. It’s always been easy to write music for his lyrics. I don’t know why. (I worked on four albums with Alexandra on major labels.) Working at Purple and with Alexandra Roos songs started popping into my head, many of which have been recorded. I was also rehearsing with Sonny Simmons—a world-class saxophone player, and a true artist from that other world of musicians—though we never managed to form a working group.

Songwriting gave me added insight into art. I think it was Arlo Guthrie who said songs are like fishing, you just don’t want to fish downstream from Bob Dylan. Songs are like perceptions set into melodies with words. Songs write you; you don’t write them—or something like that. Songs arrive unannounced like stray animals already formed but needing care. I’ve made songs from melodies I dreamed, and from picking up the guitar and something unexpected happens with my fingers. Words follow because I’m always playing with words, idiotically for the most part. Melodies give shape to word sounds that can make sense or not. It’s a gathering of perceptions. They aren’t related to concepts—at least for me.

I don’t think I’d have had any of these thoughts had I not been a musician first. Music isn’t about material things; it’s about filling time and space. I have no materialist ambitions, except for my two kids—luckily I have a teaching job and get paid to write. The standard musician joke: What’s a musician who just lost his girlfriend? Homeless. Maybe I’d have been a more successful writer had I been able to stop playing. I couldn’t—and can’t. I’m still playing, and would like to play a lot more if the opportunity came up. I’m a divided person: writer of words, improviser of music, and songwriter.

That’s some heady stuff. Well, seems to make perfect sense that your album Météo found a home among artists (by way of photographer Giasco Bertoli) as part of zingmagazine. I’d like to speak more about Météo. If I’m not mistaken, météo is French for “weather”. Can you give insight to this title and how this album came together?

I was having dinner with Giasco Bertoli back in June of 2014. He’s my close friend, and I’ve made music for his short movies. I was talking about recording songs in French that I’d written with lyricist Gerard Duguet Grasser, for other albums. We’ve made many together. Giasco suggested Zing, so he contacted you. And y’all produced it, for which I thank you very much. That same June, 2014, I visited my friend, Bob Coke, a musician and sound and recording engineer, to ask him to do the recording. I played some pieces on his Martin acoustic guitar, which he recorded. Bob is a very busy guy. He was about to go on tour with the Black Crowes, I think, and would be gone for the summer and most of the next year. So I didn’t see him again until September. And as it seemed that you guys were in a hurry, and as Bob was very busy, we did two short sessions. We winged it. I recorded electric guitar and vocals—no click track, one piece after another. As a kind of atmosphere, I talked about the weather. Bob came up with the title Météo—which does mean weather—and the titles “Ionosphere,” a single track with a glitch from in his computer that we liked, and “Averse,” which means “downpour.” He spliced together bits of the acoustic guitars I’d recorded in June with September session, and mixed everything. A couple tracks—“Centre Commercial” and “Zone,” I think—are panned, with vocal on one side and guitar on the other, so it can be listened to differently, more vocal or more guitar. I pounded on the strings for the rhythm sound in “Centre Commercial.” Bob whacked a tambourine a couple times and sang the falsetto track on “Zone.” We had fun. Bob was my collaborator. Giasco was the curator, the organizer, and shot the cover photograph of the word Oui written on a window, and the goose standing on the pond at Versailles. Giasco always liked a CD I made in 2000 with sound engineer, Jean-Jacques Palix, called “Everglade”: 14 tracks, only guitar. He wanted to repeat that. For “Everglade” I had several themes, and Palix made loops I’d improvise over. Météo was originally going to be French songs. That changed as I played and time was tight. Had we had more time it would have been longer than seven pieces—three instrumentals and four songs.

As a non French speaker, I’m intrigued by the lyrics. Can you tell us what these songs are about?

Gerard basically writes little movies. His lyrics are very visual, like imagist poems, with a kind of dark beauty. “Pescara” and “Centre Commercial” are like traveling shots. “Pescara” is about the town in Italy. The song follows a guy on a gray night, through the town where it’s rained for a week, passing stores, weeds, trees, snails, workers, seeing the unimaginable sea between buildings, feeling in every rain drop unimaginable power, where the color becomes uniform like a marching army; his eyes fixate on a boat as he walks toward the beach when suddenly the sea appears before his eyes, the sea is there. “Centre commercial” is another traveling shot entering a town, something like in the opening of Citizen Kane, seeing signs, old plaster walls, three electric wires lining the sky, billboards, and a woman—a personage—a cashier in the shopping center, she crosses her legs as two cans crash together on the counter. In the parking lot two cops get out of the car, slamming their doors simultaneously. They walk toward the store and the cashier re-crosses her legs. That’s it. “Zone” is about a guy, a dreamer, doing nothing, watching an old film in at five in the afternoon. It’s very ironic—French ironic. Gerard doesn’t name the film (The Specialist), only the actors, Stallone, Sharon Stone, Eric Roberts. He hears a siren and sees a yellow moped. In the song’s bridge the dreamer imagines buying an old Buick, polishing the chrome, taking a break every once in a while. The refrain repeats the phrase I zone in front of the TV and count every second of my life. It’s a character type that the French imagine from American movies. “Y fait encore un peu somber “means it’s still a bit dark—a baby cries, his linen jacket itches, it’s late. The cleaning lady crosses the courtyard. He does the same. He sees what she sees, the cracks in the cement, paper wrappers, dog shit. The baby cries beautifully but the sky is menacing. The old lady stops at a door to breathe. It’s still a bit dark. Gerard and I have made many others.

Can you give us recommendations for other recordings of yours to investigate? And do you have any plans currently for new projects?

Since living in Paris, I’ve worked on four albums with a French singer, Alexandra Roos; Gerard was the lyricist. I’ve recorded a number of times with David Coulter (formerly with the Pogues and was recently Marianne Faithfull’s musical director) and also with sound-engineer/dance music composer, Jean Jacques Palix with whom I made Everglade, including a television documentary on William Styron, where I played solo guitar, as well as recordings I can’t remember. I played on the soundtrack for a movie about saxophonist Sonny Simmons. I made a CD of songs, called Battle Songs, produced by Richard Prince and Dike Blair, now available at tunecore.com., but originally included in a box of artists’ multiples, ten artists in all, called “The Rowboat Box,” produced by Galerie de Multiples, here in Paris. I’m currently working on a new project with a French singer/songwriter, Pierre Genre, of songs, with a lot of improvisation, which we hope to start recording in June.

Photo: Ada Yu

Geraldine Postel is a purveyor of ideas. Through her company Outcasts Incorporated, Geraldine has operated in the realms of media direction for top art and fashion titles, independent book publishing, and installation production, including a series of “Ideal Offices” as envisioned by artists, writers, and interior designers. Recently, she has initiated a more traditional gallery program under the Outcasts Incorporated aegis at her space in Le Marais, with exhibitions by Paul Mouginot, Devon Dikeou, Thomas Lelu, Les Kebadian, Larry Clark & Eugene Ricconeaus, and Laurent Saksik, among others. On top of all this, Geraldine is at work on a novel that digs into her past to fetch memories of accidents of youth—both those that are happenstance, and those we provoke. Fortunately, she found the time to conceive a cerebral yet tactile and pointedly personal project for zing #24, “The Intimidation of a Blank Page”.

Interview by Brandon Johnson

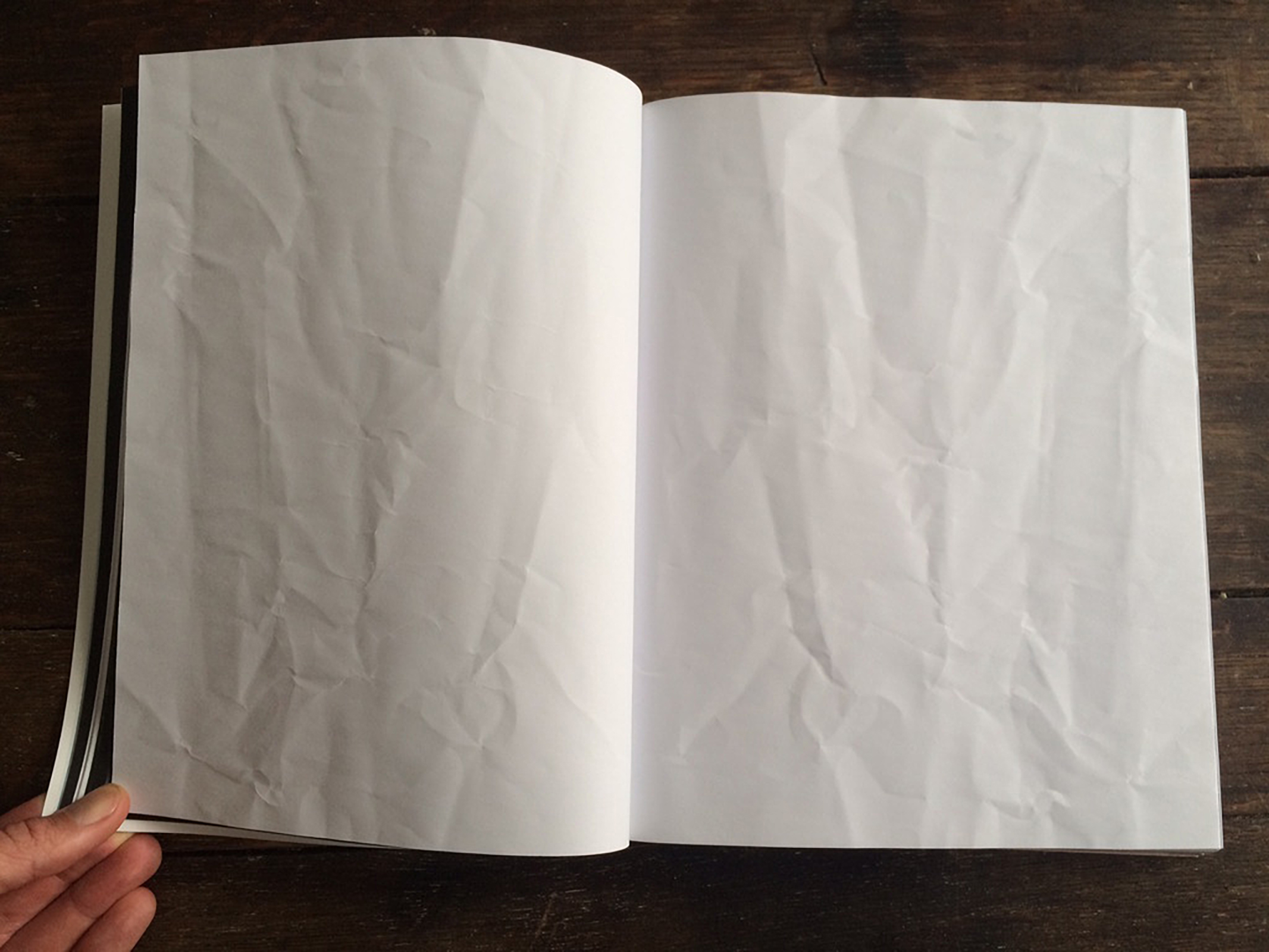

Your project is probably the most conceptual of all in this issue. How did you conceive of the idea?

In 2014 I was at the height of a serious illness. I was poisoned by pharmaceutical treatment. It was impossible to concentrate or to get anything done, or even to just accept my condition. It was unbearable. This is when I got the idea for “The Intimidation of the Blank Page”. It initially came from the frustration of this state of being, the feelings of numbness I endured along with memory failure, a long period of disenchantment and depression. It was early August in Paris, and I had been struggling with the writing of my novel for five years. The wrinkled signature project went through several phases, but then I decided to run it all white, as the title indicates “The Intimidation of a Blank Page”. I remember that Devon [Dikeou] preferred that as well.

The project engages very closely with the material and production aspects of the magazine. Can we attribute this to your background working in publishing industry?

Evidently, I’ve had a relationship with magazines since birth. My great-grandfather had published an almanac each year during the 1920s. I suppose that my heritage in print and love for books comes from this part of my family. To arrive at this idea of blank pages and to give them a wrinkled aspect was a really fun challenge. It suddenly became my goal to make a 3-D project in a 2-D publication. How feasible it would be to do as an insert, and so on. Yes, it must be intrinsic to my relationship with magazines, my quest for the new, the creative, and the different in publishing—similar to what I have always done with Outcasts Incorporated. I love and also hate this project for the same reasons—the freedom, the message (or non-message), the consumerism, the waste of paper, the circulation, the way people can rely on pages and spreads (or not). From laughter to boredom, rage, surprise, and even disgust sometimes, you have the chance to find something in a publication that blows your mind or triggers something positive in you. If that happens, you’ll close it and say, “Hey! That’s a great magazine!” But that’s rare. Not to be flattering, as I have been involved with this project [zingmagazine] of Devon’s since 1995, but that is still the way I feel about zingmagazine. It’s always a great surprise to receive it, and there’s always great stuff that will reinforce my idea that it stands as the best pure art magazine of the last two decades.

The “intimidation of a blank page” seems to imply that there’s anxiety present in the act of creation. Do you feel this is true?

Hell yes. I am so full of images after all these years of constantly studying visual references. I was trying to propose something different and personal, something daring that plays on notions of the relationship to inspiration, creativity, the predisposition to do things or not. All our psycho moods relentlessly transporting us through the spectrum of emotions, along with everything else that interferes with our creative needs. Another big part is ego. I was really frustrated and wanted to do something creative.

It’s a daring act to present a project of blank pages! Does this at all speak to how the reader/viewer tends to project their own inner concerns or ideas upon a work of art?

I consider all new encounters—readers, passersby, and viewers—to be like a blank canvas in the first process of receiving images. The reader receives it, then processes it, and their emotions, experience, and knowledge will eventually give them an intuitive or conceptual answer as to whether they like it or not. It might also seem a bit humorous. In fact, that’s part of the intent—a sense of humor that should be taken seriously. I think that humor has a lot of truth in it. One should laugh at oneself more often to counterpoint our certainties and self-entitlement. With this curatorial section in zingmagazine that was generously offered to me, I acted upon that feeling. It became, “Oh yes! Let me communicate this feeling of searching for oneself in a cluttered world of images and words, when confusion takes over.” On the other hand, I hope people find pages on which to meditate upon the beauty of the random creases and whiteness of the landscapes, the feel of the volume of the paper, the ephemeral, the subtle hurricanes passing by. Yet, I have to add that in spite of how beautiful and proud I am of this section, I need to say that I also feel bad. I have a moral conflict about the use of trees—paper waste—because that matters to me. So many useless, ugly, and odious magazines are distributed in the world! What a waste of paper! What I do know is that I am not selling anything here with that piece. I am only communicating ideas. So looking at the project now, with your questions in mind, I also have these mixed feelings about myself—like facing a mirror of my own vanity, denunciations, and failures! Yet the project still stands out because it says many things without using words. That’s another dichotomy very intrinsic to my personality, which relates to this title. I need a bit more wisdom and self control. Let’s hope that will come with age and more of this kind of experience . . .

Despite the ambivalence you’re expressing, I’ve been witness to many positive responses to your project in particular. The moral dilemma of creating something worthy when using a material like paper is understandable as we become more conscious of our use of natural resources, but perhaps that’s the very reason why you have created a project that can only really exist in this medium?

If I had the proper time, support, and space (along with many other “ifs”) I could attempt to realize creative concepts in many other different mediums, and it would never be the same. Indeed, this section is dedicated to zingmagazine. I had a great time, it took my mind out of burden for a little while, it looks great, and I am just as glad to be able to discuss this with you today. My projects usually start with many wrinkled papers, so let’s call it a new beginning!

Francis Cape, Utopian Benches, 2013 (photo by Aaron Igler)

Nestled in upstate New York, Francis Cape reflects upon the local histories of Utopian Societies and their shared objects. With his project “Utopian Benches” in zing #24, Cape samples a much larger path that includes 25+ carefully measured and carved benches, a comprehensive book, and a now global dialogue about communal societies and their unique benches. Trained as a woodcarver and holding an MFA from Goldsmiths College, Cape creates various furniture installations that reference both historical and contemporary societies and their politics. Bringing these historical benches into contemporary relevancy, spaces, and dialogues, Cape makes us think about the histories of alternative, intentional communities. These benches that once lived outside of mainstream culture are brought into art spaces to remind us of idealism, orientation, and non-hierarchical conversations that can still exist in a very materialistic, hierarchical art world. Leveling us to an even playing field, Cape’s work brings forward a much forgotten history in the US and a much needed reminder that we are all after all, equals.

Interview by Madeliene Kattman

How did you become interested in benches from utopian communities in the first place?

It came out of what I had been doing previously, and that work started when Bush was re-elected in 2004. I decided I couldn’t continue with what I had been doing and needed to make work that somehow addressed the current situation in our country. It took a while. Initially there was work that dealt with post-Katrina New Orleans, which wasn’t just about New Orleans and the storm but also about class and poverty in America. From this, I was able to move the conversation to where I live in upstate NY. This more local body of work is called Home Front, and used something called the Utility Furniture Scheme, which was a wartime British furniture design scheme. I used it to talk about idealism, dreams for society and the relationship between idealism and material culture.

When I talked about that work to peers and students, I started getting some pushback particularly about Home Front because I was using a British model to talk about American society. So I decided I to research social idealism in America, and ended up with these Utopian Communities (the correct term is actually intentional communities). I then discovered the benches, which are the perfect symbol for communalism, in that a bench is something you sit on together, you share, it is non-hierarchical—you sit at the same level. Initially there was one Shaker bench here in the studio and it was the best thing I made in a year, so I just started making more benches.

Are a lot of these Utopian Communities abandoned?

The historic ones are, with the one exception of the Hutterites up in Canada who are still very active. They have been in existence since the late Middle Ages. But the historic ones in the United States, the ones we all think about—with exception of the Shakers—such as the Harmony Society, or the Separatists of Zoar, they lasted for about a hundred years. These are mostly now museum villages, so the material culture is preserved. You can travel to them—you can go to Old Economy village in Pennsylvania, you can go to Zoar village, or Amana in Iowa—and take tours. I had the privilege to go behind the scenes, jump over the braided ropes and measure the benches. The benches are now preserved by curators who are in charge of the collections, and who were very welcoming. They were happy for me to work with their collections and bring them to relevance in the contemporary world. The contemporary communities were also very welcoming and I had great visits with them. I actually continue to have relationships with two of them. Particularly with Camphill Village in Kimberton Hills. My guide who’s the art therapist has become a good friend. I stop in and see them and she stops in here when she goes to see her in-laws up in Albany.

So you’ve developed a relationship with the people who work there now?

Yeah, I actually had an existing relationship with the Camphill Villages, not in the United States but in Britain. My brother lived on one for a while and a couple girlfriends moved to them. So I was already familiar with them before I began making the benches.

Are you originally from Portugal?

You know, I was actually born in Portugal but my father is a British diplomat. So I am British, although I spent many years in places around the world.

How do you choose to display the benches in various art spaces?

The benches are always displayed in the same way, gathered in the center of the room in a rectangle. The reason doing that, for arranging them in the center of the room, is that in museums and churches benches are used as objects to sit on and look at other things. I specifically didn’t want that to happen with these benches because they are about themselves and so they face towards each other. So far as any of the benches have a front and a back, the front is always facing towards the center of the group and then they are aligned longitudinally in the space. Within a church they would be facing the altar at the one end, instead of which I arrange the rectangle long ways.

Within the exhibition space the benches are used to hold conversations, meetings, and discussions. The dialogue is set up so that whoever is leading the conversation sits on the benches with everybody else. It’s not like there is a panel discussion or somebody leading a lecture who is outside the group. This isn’t audience seating, this is participatory seating. While the benches were in San Francisco they wanted to mic me and the gallery director, with whom I was leading the conversation. I said you can only mic us if you mic everyone else. Ultimately, this project is about sharing and everyone being on the same level. I am very insistent upon the placement of the benches but I am less firm on the format of the conversation, as the work is about sharing. When it is shown I send out guidelines, but it’s up to each venue to do what they will as they organize the conversation during the exhibition. However, some places have used the benches as what I call uncomfortable audience seating, which is not my intention. But that’s just the same as sharing and living in a community—you accommodate other people and their views.

The benches then also exist in an exhibition booklet that is printed for each occasion. The first version of the exhibition booklet from Arcadia can be found on my website with a link from the Utopian Benches page. The booklet describes the communities that are represented by the benches in the “gathering” as I call it. The other part of the booklet is research conducted by each venue about the communal societies that are close to the exhibition site. They decide what this locality means, so the societies can be in a 100 or 200 mile radius. The purpose of this is to bring these alternative ways of living close to the audience. I want to emphasize the fact that this way of living is not something unusual that some weird people did in the past, in some other state, but that it has actually existed or does exist all over this country.

What are some of the conversations or programs that have taken place on top of these benches?

They have been very wide ranging. Each venue plans and executes their programs and conversations. At the beginning, I started to collect a list of the conversations but it very quickly fell apart. I encourage discussions on utopia, idealism, communal living, shared values or non-materialism, a dialogue that relates directly to the benches. There is now a European group of benches that I’ve done in collaboration with students in Lyon, exhibited for the first time last Fall. There were two conversations, with the first one about the anarchist Pierre Joseph Proudhon, who was born in the city where the exhibition took place. The other was led by the director of the second venue, which is a Fourierist communal site, and was about Charles Fourier who was a utopian, socialist philosopher who was also born in the same city.

Were the students a part of the conversation or did they facilitate it more towards audience members?

This was different. So the Utopian Benches that I showed in zingmagazine are the original, American benches. The original grouping was 20 benches, which grew to 24 then began to splinter off. Now there is one collection of 17 permanently in San Francisco and a smaller group of eight that is still touring. Meanwhile, I was approached by someone who teaches in Lyon to do a workshop with their students. I proposed that the workshop would be about European communal societies with the purpose of making a European collection of benches. So the workshop that I did with the students in Lyon included research parameters, process and discussion. The students then went and found the communities, measured the benches, and raised some financing for the benches to be made in a professional workshop. The students also participated in the construction process, which we wanted as these were design students rather than sculpture or woodworking students. They saw the project the whole way through. By the time we showed the benches for the first time, they were onto their next project, and since the exhibition was in a city about two hours away from Lyon only two of them came to the opening; but they were not a part of the conversation. The students handed it off, they shared it with the museum. I shared it with them and then they shared it with FRAC Besançon.

That seems really cool.

I think so too. I love the way this thing has just sort of taken off on its own. You’ve seen the book that was published by Princeton Architectural Press?

I was about to ask you about it. How do you feel the benches function differently from their exhibition spaces like at Murray Guy versus publication spaces like your book entitled We Sit Together: Utopian Benches from the Shakers to the Separatists of Zoar or even zingmagazine?

Well they’re all very related but the experience of walking into an exhibition of the benches is of course radically different from picking up a book or a magazine. There’s no way that seeing a photograph is the same as experiencing the artwork in itself. The book is a different but related work. It’s not a catalogue of the benches, it’s its own thing. It came out of the exhibition booklet, which is what the publisher approached me about developing. Through the book, I took it into this realm of describing the various communities through their benches. I describe the communities, their beliefs, ideology through the design, the form, and the use of their benches. The other thing that it did, because we published measured drawings of the benches, was provide information where people could actually make the benches, and use it as a teaching tool. It ultimately had the potential of establishing this community outside the gallery walls. Applying the whole Marcusian notion of what happens within the gallery walls makes no difference outside of them.

What is your favorite shared space and what kind of architecture and furniture does it have?

I am not a religious person, but I did grow up a Catholic and I do really respond to Gothic Churches. In England, Gothic Churches now are not Catholic, so I don’t have the experience of really using them for religious purposes myself but they are incredible. The best way to experience them is to go for evensong. When the choirs are singing, the acoustics of the church are absolutely incredible. Just purely architecturally speaking, they are amazing spaces.

But Camphill Villages also have an incredible feeling to them. It has something to do with the architecture because there is an anthroposophical sense of design or architecture that comes from Steiner that they use. If you go to these newly built communities, the buildings are unusual by our rectilinear standards. They use organic, soft shapes instead. Because of what goes on there, they attain this atmosphere that is really lovely. In terms of the material culture, like the furniture, it’s not utilitarian in the sense of having hard, Formica surfaces but it does have to be easily cleanable. Because half or more of the people that live there have special needs, it has to be simultaneously soft, organic, natural, warm feeling, while maintaining this utilitarian function. There’s a particular kind of look that comes with this special use. My first sculpture teacher had a handicapped child and they designed and built a lot of the spaces for their daughter and came up with a very similar kind of look. There would be the use of wood, but then it would be heavily varnished so it can be wiped down easily. The edges would then be softened so if somebody falls against it, it doesn’t hurt them. There’s a kind of functionality but it’s not just material function it’s a more human function.

What artists or woodworkers do you look to for inspiration?

Well my work is very different from others, but there are of course people who I greatly admire and in the field of furniture sculpture Doris Salcedo is huge as far as I am concerned. I additionally look to artists, Rachel Whiteread, and Andrea Zittel.

What is next for you and your work? Any planned exhibitions or projects for 2016?

Some of my time is still taken up with the ongoing tour of the benches in Europe. I am collaborating with the Lyon students on drawings to be shown with the benches at the next exhibition that opens in April. Then I’d like to expand this European gathering of benches by collaborating with another community of students or others to research and fabricate additional benches. And meanwhile I’m developing new work in the studio. That is still in the development stage, so too early to talk about.