Photo by Tomas Soucek

Romana Drdova is a visual artist from Prague, Czech Republic and has traveled to Seoul, China, Paris, New York and beyond studying and perfecting her craft. Her work explores different modes of communication, expression, and transparency in a “data smog” filled modern world. Using her 2D and 3D art installations, photography, fashion design, assemblage and mixed media, Drdova questions what it means to live in this day and age, how we interact with our environment, and how our surroundings impact our personal experiences.

Interview by Mauricio Rocha

Your work in zing #25, “Mapo Tofu Masks: An Asian Love Story,” explores people’s relationship with technology, food, beauty, fashion, and more. How has your time in Korea and Prague influenced your work?

I went to Seoul as a student with a scholarship and spent an absolutely exceptional time there. I learned how Korean people take care of themselves in the terms of how they eat, how they care about their skin, how important is for them to spend time together, among other things. I couldn’t have imagined how much it would influence me to stay in Korea. When I came back to Prague, where I am based, I started to understand that my destiny is to cultivate my work through this fascination and emotions that I have from Asian culture. I would say that I work like a translator of these emotions to my own language or maybe a better explanation is that in my soul is a recorded hardware with information which matches with those Asian memories. Someone might call it karma.

I enjoy seeing the inspiration from your environment in your work. What are some of your favorite places to visit and work in around the world?

I like the contrast of places I’ve had an opportunity to visit. I have a special bond to China. I consider this place to be the beginning of our civilization and it will probably be associated with our demise . . . but perhaps it should be like the natural circulation of everything, life and death. In Asia I feel as my real self and calm. On the other hand, I love the hustle and bustle of New York and the openness in communicating with people, the freedom they show on the streets. This makes it extremely unique and inspiring to me.

Photo by Tomas Soucek

The face masks you designed are an extension of your work in the magazine, provide a 3D element, and can even be categorized as an art installation. Does your artwork usually feature a combination of art and fashion?

I had to find my own way of expressing myself as a necessity. The combination of art and wearable objects that are fashionable has certainly defined me since my childhood. I am not someone who speaks loudly and is confident in verbal expression. With pictures and text I can say what I can’t verbalize and if I can wear it as clothing, then it is easier to express who I am. This is self-confidence. I always get drawn to a more complicated approach to creation, using layered meanings, but I believe it’s very similar to learning a different language. You meet, fall in love and learn from each other. During my practice I have met so many interesting people and stimuli with similar feelings and I can give them a new insight into the matter. And that’s why I do it. I want people to wear my clothes, to see it in surplus value and to be happy with them. I don’t want to exhibit only in galleries where you feel a distance to objects. I want people to have a real experience when they buy my product.

Do you usually take the photos in your projects yourself or weave them together as a collage?

It depends on topic. Usually I spend days to find visual material that fits to my ideas. Actually I prefer both. My favorite discipline is assemblage; it is more combination 2D with 3D objects in the space or on fabric. After that I am able to sew clothes with clearly given motives or to cut fabrics freely and the result is intuitive improvisation. Now for example I collaborate with French performer Arianne Foks on a series of coats, we are writing texts and taking photos as daily memories. The topic of our work is current and alarming subjects such a global warming, women’s rights, breaking social values, false and true, transparency etc.

You mention a “data smog” in our recent climate, what do you mean by this?

“Data smog” is more metaphor than literal expression. I use this phrase as an explanation for an endless number of stimuli overloading our organs under the weight of everyday pressure that society creates. I first used this term in work from 2015 when I created protective shields against the bustle of city. They are made of plastic with headdress and you can decide if you tilt the shield down or allow people to see your face. It has a purpose: you can see people, but others can’t see you. I was confronted with controversial views from passerby. But I believe we all have the right to privacy and rest when we want it and no one can complain because I look differently than others.

Your work features several foods: sushi, rice cakes, popcorn, rice, gummy sharks, and marshmallows. How do you view food in this “love story” you’ve created?

Eating is very important for every culture regardless of which content it is. I used these fancy motives thanks to their easygoing narrative. There is an immediate link to Japan, infantile style or kind of perversity. I started with masks as my diploma work 2017 as a part of a bigger project with trash recycling. I spent a few months in Beijing before that, and my work was inspired by the inability to keep this incredible amount of newly made things and that which we throw away on this planet. I rented the space and opened “shop” with trash I collected for 5 months. This trash contained plastic bottles, polystyrene, all kinds of weird plastic materials . . . and I installed them at the shop. Customers could come in freely and buy it, take it, and discuss its problems. And of course, part of this project was cooking and preparing of sushi, because it’s easiest and effective. Now I am preparing my second collection of masks as a continuation of this “love story”.

Photo by Julie Hrncirova

What are some of your favorite foods?

I prefer Asian food preparation. My kitchen looks that way too. Haha. I like to discover new tastes, for example, I am currently fascinated by varieties of flavors from Laos, which I first tasted at the Lao Siam restaurant in Paris. They offer banana salads and such delicious tapioca desserts; it was an absolutely excellent experience for my taste buds.

I think a universality in your work is that we are all looking for love, and for food, as both are essential to our survival as humans. Would you say that fashion and art are just as essential for humans?

I would not say that fashion and art are essential for humans. I would say that they are surplus value that we can enrich our lives and minds with. It is a nourishment for our spirit and inner world that each of us can cultivate.

What projects are you currently working on and what can readers expect to see from you in the future?

I started new mask designs for 2020, now I’m preparing cuts for coats with a similar theme. In spring I have a big project based on the circulation of materials supported by the National Gallery in Prague. A great inspiration for this exhibition was staying in New York and my own work from materials that I had the opportunity to obtain at Materials for the Arts. I would like masks and clothing to be brought to the attention of as many people as possible and to make them happy and enjoyable.

Since 1989, Craig Dykers has established architectural offices in Norway, Egypt, England, and the United States. His interest in design as a promoter of social and physical well-being is supported by ongoing observation and development of an innovative and sustainable design process. As one of the Found Partners of Snøhetta, Craig has led many of Snøhetta’s prominent projects internationally, including the Alexandria Library in Egypt, the Norwegian National Opera and Ballet in Oslo, Norway, the National September 11 Memorial Museum Pavilion in New York City, the San Francisco Museum of Modern Art Expansion in California, and the Ryerson University Student Learning Centre in Toronto, Canada. Recently Craig has led the design of the new pedestrian plazas in Times Square and The French Laundry Kitchen Expansion and Garden Renovation in Yountville.

Interview by Brandon Johnson

Your work as an architect is well-known. But your project “Observationalist” in zingmagazine #25 features your photography. What sparked your interest in this medium?

Photography in and of itself is not a standalone technology for observation. I use multiple methods of observing people, activity, and things. Sometimes I sketch, sometimes I commit things to memory, I might be listening to sounds around me so I have recorded audio in the past. And the way I use photography is to capture a very quick snapshot of something. If I need to move quickly, the camera can capture something that I see and allows me to continue moving. Whereas sketching and other types of technology take up more time. I would say that it’s more about capturing moments in very quick succession. It’s a form of note-taking. I don’t see these photographs as a form of artwork or a representation of the photographic medium. It’s the content that is driving it. I am not much of a photographer otherwise. It’s very important to have the right kind of camera. So as cameras became digitalized, to a certain extent it became easier to take these types of photographs. You can be walking and a take a photograph in a different direction, so you never need to hold the camera to your eyes. It’s just more relaxing. Not only for me, but also for people on the street. As soon as you put a camera to your eye it changes the context. I’m trying to capture things as much as possible exactly as they are in that moment in time without preconceptions. Free of the distraction of the camera to the subject or my own artistic intent. When you’re walking with a camera at your waist, it’s very hard to control. You’re not thinking about how to frame the photo. You just snap it. With a couple of those photographs it does amaze me sometimes when you look back at them after you’ve taken them that you’re able to capture an image that seems well-balanced or seems to be as if it were posed or at least framed in some way. I think that’s an interesting point. You can use a quick response technique to create something aesthetically appealing. There’s something about intuition, and not just of the mind but of the body.

“Observationalist” gathers your conceptual yet casual photos of people and things, organized in loose, and often humorous or absurd, association. Had these associations crossed your mind previously, or did it materialize more as you organized this project?

I would say more intriguing to me is not one image in itself, but the comparison of the images to each other. Many of the photographs are of humans. And many of the photographs are of objects that humans make or acquire. The artificial world and the human world being compared to one another. There are invisible strings of meanings between them. Sometimes I try to make those connections more obvious. It tells us something about intimacy, which is a challenging subject. For those of us that live in cities, intimacy is a luxury. That’s part of the thinking for those images being next to each other. Again, I don’t see these entirely as works of art or photograph. I see them as fictional narratives. I don’t very often show them. The last time I did that, by framing them and sticking them on the wall, would make it seem like a photograph, which isn’t necessarily what they are meant to be. So I printed them very, very small, about the size of a thumbnail, and in a strip, like a ribbon. From a distance it just looked like a thin colored line, but when you got closer could see they were photographs. In order to actually view them I gave people prescription glasses that I found at a junk sale. The prescriptions would different, so you would need to stand closer or further accordingly. Then you could go along and see these images magnified. There were a couple different kinds of frames. Some were horn-rimmed, and others 19th-century wire-framed. You could test out a couple different pairs. In any case, you had to get very close to see the pictures. But the point was that it was a different experience than seeing them in a gallery on a wall.

I can see why this would work given their sequential nature. And I can see why it worked so well for our format as a magazine, which is also sequential in nature. Each photo has its own story as well.

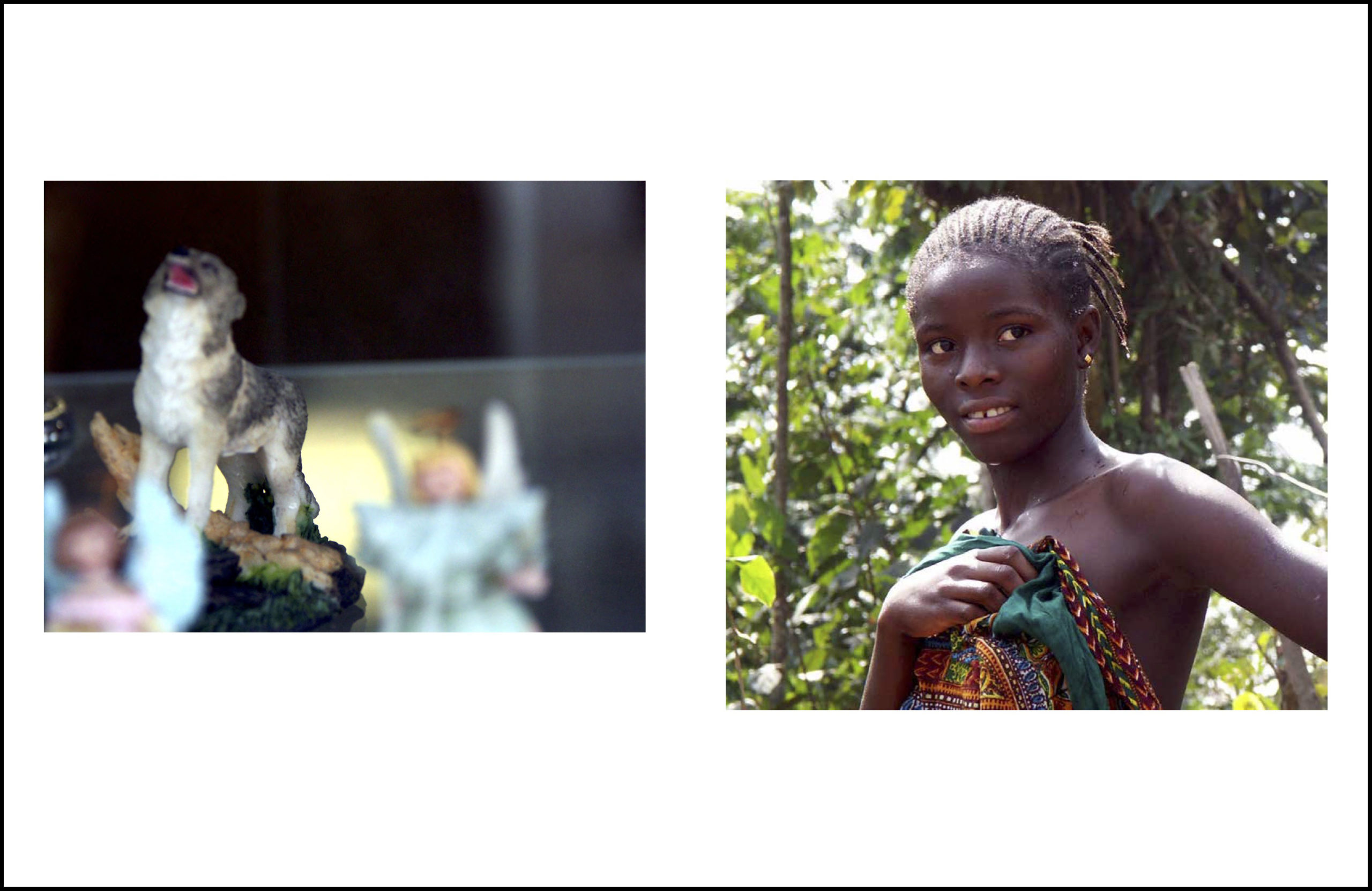

I love that fact that you flip through the project one after the other, and there isn’t a clear description telling you what each one is. The size of the magazine is very nice as it allowed us to use white space in the layout, which I thought was important. There’s a lot of air. And the photos obviously have stories for me. Each is quite special. One photo is of a young woman I met in Guinea, West Africa. I had been traveling through in the countryside, and part of the reason I was there was to understand better what drove people in countries like Guinea and around the world to leave the countryside for cities. We like to talk about how the majority of people of the world live in cities, over 50 percent, but I was trying to understand that statistic, because many people say it with great pride, but I thought there was something strange about that. I went out into the countryside of this place that was just stunningly beautiful, and yet so many people were leaving their villages for the capital Conakry. I was interviewing people and talked to her and she said most of the young men had moved away due to the idea of economic improvement. When I asked what this meant, she didn’t really have an answer. They go to the city looking for money, and in fact don’t find it. It is a complex situation. And all of this beauty and contradiction I read when I look at this image. These stories in my mind are not anywhere in text form, but I feel is embedded in the images somehow.

Your account from Guinea brings me to how the act of observation is integral to your design process, social interactions and how people live. As busy as you might be overseeing a big architectural office, and with other distractions vying for attention, do you make a point to set aside time for observation?

I try to as much as possible. It gets harder and harder as time goes by, but I do. And I’ve even done very unusual things. For example, I’ll fly into a place and instead of taking ground transportation of any kind from the airport to where I have to go, and I have a lot of time, I’ll walk instead. You sense a place in a very different way walking through parking lots, the leftover spaces in between parking lots, through loading docks of some strange big box building to get to another street. Crossing into some forgotten about residential district near the airport, and continuing to walk along larger roads trying to avoid dangerous situations with cars, along the side of the freeway. I’ve spent sometimes five hours walking. I’ve never had a rolling suitcase, only a shoulder bag. It allows me to be pretty mobile when I need to be. So that also allows me to observe things in a very different way. The problem these days is like many I held off on using my phone as a camera for so long, and unfortunately now am using it more and more. I liked holding a camera in my hand. It was heavier and you could feel its purpose. The phone has so many purposes, it’s just watering everything down. Furthermore, the reason you take pictures is so broad now—some for yourself, some for your friends, some for social media, some to record something you need to give someone. It’s now harder to remove the images from your phone/camera. I haven’t been carrying my camera as much as I used to and am a little sad about that.

An object with a single purpose infers more intention?

I want to get a typewriter too. I’m a really good typist. I learned at school at a very young age. And I learned on a typewriter. But that’s another example of an object with a single purpose. You can only write things. You can’t stop, push a key, and then browse the internet, like a computer does. So I’m thinking about reintroducing that to my life. A typewriter and getting my camera back out. This, by the way, doesn’t mean I don’t like computers and other technology, I just find that balance is important. And some of the photographs are talking about that—the difference between a handmade or authentic situation versus an artificial one.

During our initial meeting for this project, you told us about your collections of tchotchkes. In your essay, you say that “looking at man-made objects reveals our deeply seated motivations.” I’m curious as to how these two things might relate—collections of small, decorative objects as manifesting something deeper, and how might this relate to the photos in the project?

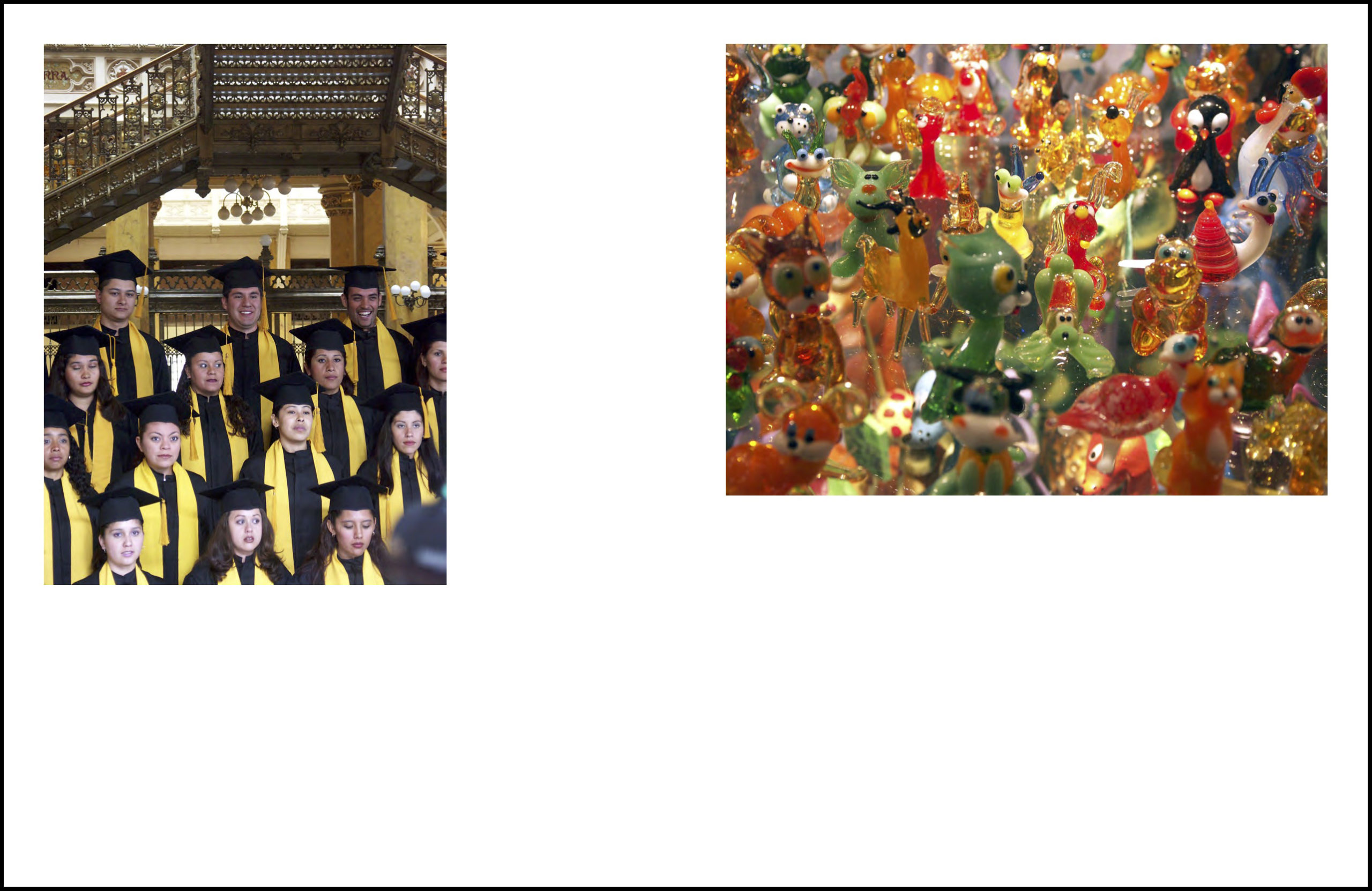

Well I think one of the reasons that we occupy our minds with art on all of its levels is that we want to learn something about ourselves and the people around us somehow. We want to dig deeper into our minds. Some people have dug into their mind for a long time, so they have to dig deeper. And that type of art can be more conceptual, and harder to envision what it is. But many people don’t have the luxury of digging into their minds every day, trying to understand their existence. They have to work like hell to put dinner on the table. Those people see art as something that is just letting them understand who they are and that they have some kind of significance. They don’t like to be alienated. It’s not art the way most of us would think of it, but to them it’s a form of art. An object, something that was made by someone or something else, and it tells them a little story that they can imagine. A lot of these things that I photograph, the kitsch objects that a large percentage of the world buys. And I say that, because everywhere I go, anywhere in the world, there are these things. Not just in Philadelphia, or Hamburg, or Venice. They’re in the most remote places. Clearly, they have significance for us. They tell stories of fantasy and romanticism, how we project our own desires, our own view of ourselves, into the objects that that fill our spaces. These are very inauthentic things that still are authentic, in a way. The trolls kissing on the bench are only objects, but similarly, all of us want to have that moment to have that kiss and not care if anyone is staring at us. Or it’s the ceramic dancers next to the women with similar make-up. They have the same eyes. Or the pictures of the graduates in Mexico City next to the glass figures from Krakow, Poland. The people are dressed the same, but each feels very different and special, just like all the glass animals. There’s something they are desiring, and if that doesn’t happen then maybe they will go out and buy these glass animals and fill their shelf.

Ultimately the meaning of these objects only comes in relation to people and the meaning these people impart on them?

That’s correct. And then the question is whether this is true for anything—conceptual art, vernacular architecture, contemporary architecture. It’s true for everything. But we just pretend there’s a civilized way of seeing things and a less civilized way of seeing things, but that’s in my opinion an artificial distinction.

Photo: Michael Grimm

In other publishing news, Snøhetta has just released a new monograph with Phaidon, covering 24 projects from the last decade and their evolution over time. Can you tell us more about that?

These are all built projects and furthermore all documented in their final forms, more so than the design process. As much as possible we try to capture images of our work with people involved. And this happens after building is completed and in operation. The emphasis is with trying to connect people with the building. And you need to think about all the levels of being, the way we exist in the world, in order to create the right environment. That is partially why I take all these pictures of ordinary people; there is value in observing ourselves doing seemingly simple things.

The projects in our book are from throughout our history and are divided into three themes to give further insight. The reason for this is that if we tried to unpack every project and all of its themes it would be hard to read. So we singled out some of the themes, for example politics in the space of society and civilization and how you negotiate that. Another is about generosity, and how if we are to socialize as creatures in larger civilization, there has to be generosity in order to survive. We try to create places that allow for that and collective ownership. The last has to do with our transdisciplinary process and how having multiple groups working together in a studio, as a collective, impacts the work. Many architects think they can do everything themselves and only need other people to tell them they’re right. We don’t do that. For instance, we have landscape architects working alongside architects, informing each other, arguing with each other, pushing the limits of what we do. We have branding and graphic design, we have product design and interior architects, all working together in a collective manner.

How important is publishing to Snøhetta’s practice? And did the office learn anything from the process of putting together this book that might benefit current or future architectural projects?

We have a history of not publishing. For a long time, we said, why should we publish? We design buildings. Other people can publish if they want. We didn’t want to self-author it. This was part of our feeling that we didn’t need a manifesto, but that was at the very beginning when we were younger. As we got older we realized that publishing was an important part of the process, not only for sharing our work with others, but also learning it ourselves. Because in making a book, when you are forced to put the work into words, and choose images to accompany these words, it allows you to look deeper into your motivations and the consequences of what you do. So we have started to publish more books recently. For example, two years ago we did a book on our work on the new San Francisco Museum of Modern Art. That book is different from our monograph because it focuses on only one type of project and our thinking behind making a museum. So we publish in part because there’s been greater demand, and the practical matter of more people wanting to understand our work. The books allow us to give them a certain degree of information. But the real value in publishing is about writing and words. Getting used to an editor, having a collaborative engagement with someone outside of the studio or our life, that pushes our thinking in many ways.

Sarah Staton is an artist working with the social potentials for sculpture, and balances public commissions with studio work and occasional iterations of her ongoing SupaStore project. Her project in zingmagazine “Mycology and Dendrology” celebrates the newly identified wondrous hidden underground communication networks that researchers such as Suzanne Simard are identifying through careful study in recent years. Sarah Staton lives and works in London, and is Senior Tutor in Sculpture at the Royal College of Art.

Interview by Brandon Johnson

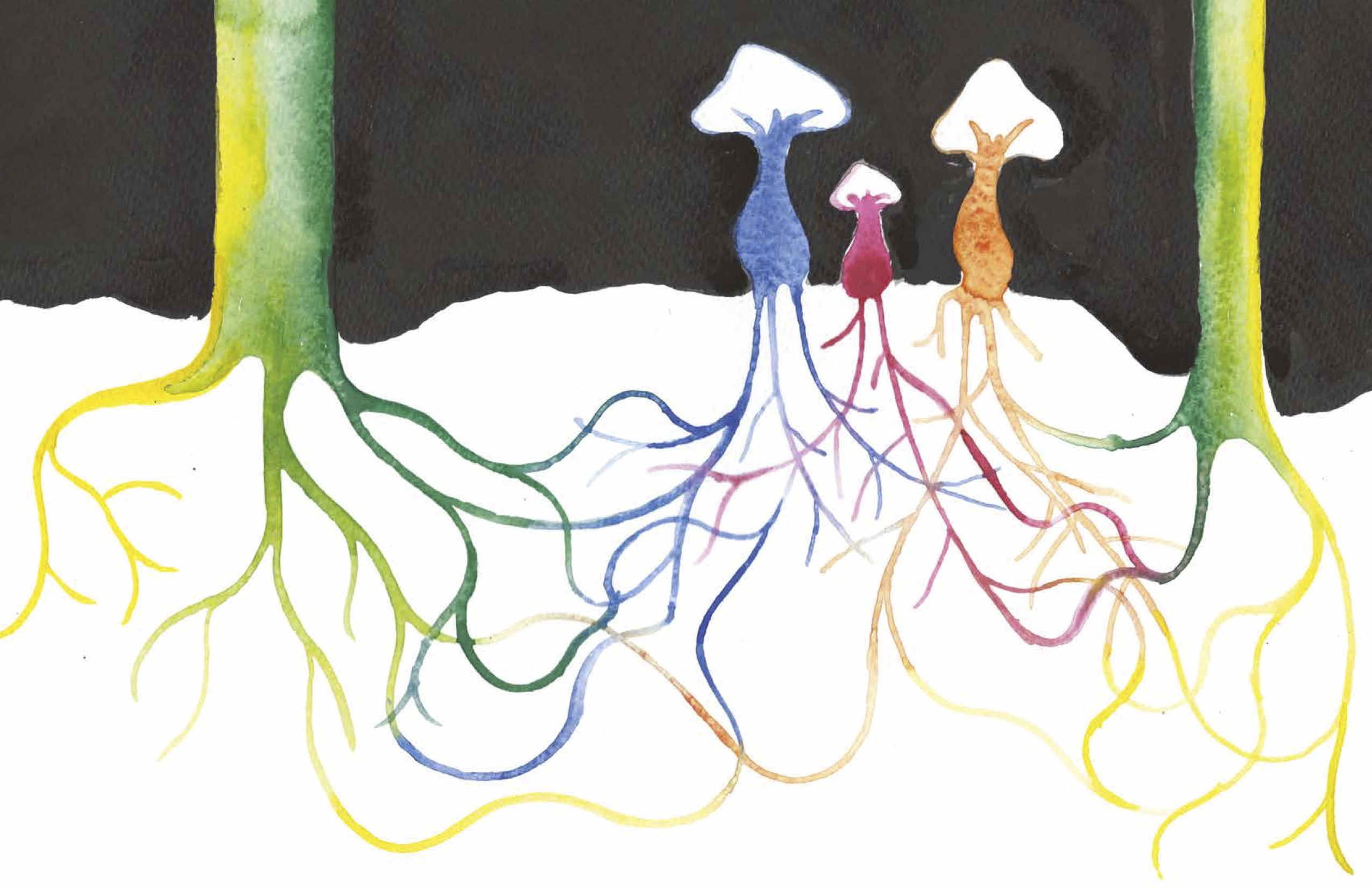

How did you first learn about mycorrhizal networks, and what about them sparked your interest as a subject for art?

Around four or five years ago I came across a text that talked about the ways trees send nutrients and water to each other through their root networks and via the nets that fungi make under the forest. This fascinated me. I looked for more information and found the work of the ecologist Suzanne Simard who has been mapping and researching this area for 30 years—her Ted Talk is excellent. As for taking this knowledge as the subject for watercolor and ink drawings, I have enjoyed the visual correspondence between the forms of mycorrhizal networks and the diagrammatic networks that I doodle in academic meetings, which also correspond to the nets that spiders make when they have been fed various drugs. These “Spiders on Drugs” nets provided subject matter for an early set of watercolor and ink drawings. Mycorrhizal networks are a vehicle for me to go forward while go backwards as it were to revisit a visual form that resonates with me, and to do it in a slightly new way.

So would you say your recent drawing practice is about representing interconnection?

I would describe these drawings as pictorial representations, and a vehicle with which to enjoy the play of color and line on paper. In this particular set of drawings interconnectedness is represented, and they are a visual note for speculations on non-sapiens sentience.

How does this fit in with your other work?

Drawing as a way of thinking—I use drawing in a number of ways, sometimes to develop ideas and methods for making sculpture, sometimes as a kind of pictorial diary/note-making, and sometimes in small series to explore ideas. The mycorrhizal networks drawings are one such small series. I see a link with the notion of interconnection with the series “Spiders on Drugs” from 2001. The mycorrhizal network drawings also connect to an exhibition that I made in 2007, “In Situ Ex Situ,” at Mount Stuart, Isle of Bute, in which I thought about the journey living wood takes from forest to home. For this exhibition, I created sculpture from pine furniture, manipulated with digital cutting (CNC), alongside Alpine style furniture that is essentially wood dust held together with resin, tracing a kind of timeline from majestic living wood to abject reject domestic furniture.

It’s interesting to think of something as simultaneously a living thing and material. A transformation takes place where organism becomes commodity, not only in name from tree to wood, but also a separation in the mind where these somehow are two distinct things where origin is lost. The essay in your project expands upon this subject. Are you advocating here for sustainability or at least a consciousness surrounding the consumption of natural resources?

To take your last point first, one might say that we the humans suffer from exponential entitlement issues: our destructive domination of the animal kingdom and our planet’s resources is taking us to the point of no return. How might we step back from the brink? Considering these nascent understandings of communication networks that clearly exist between living organic matter and between living creatures whose languages we don’t understand and sometimes can’t even hear, is helping me rethink consciousness in terms of consumption of natural resources. I find these areas of discovery incredibly exciting in terms of their potential for us to change our behaviors going forward.

In terms of considering the relation between organism and commodity, I am very interested in Peter Linebaugh’s writings in which he studies historic processing of natural resources, along with the labor issues involved in these processes. His writing reveals in some detail the specifics of working with material and in the main he looks at the time before oil transformed our range of material options so exponentially. The pernicious effect of adding oil, petrol, and their by-products to our material register has been and continues to be corrosive on a devastating scale.

Your project in zing uses a rainbow spectrum of color that bring to mind a utopian visual aesthetic associated with the hippie culture of the 1960s. Was this in any way an influence here?

Absolutely this is a direct associative reference, the aesthetics of hippie culture, that point toward content, to name a few examples—in the UK, Oz Magazine, IT and Spare Rib, in the US Bijoux Funnies, the Whole Earth Catalog—this explosive moment post-WW2 for western counter-culture. For Millennials and Gen X-Z, the rainbow spectrum may have a different reference, signifying LGBTQIA+, the double-edged sword of identity politics?

What projects are you engaged with currently?

I’ve been thinking recently about the Bauhaus education model which taught through material knowledge. As we all slip behind screens, how can retain the value of this way of thinking, in education and in the wider world too? In terms of art making, I am primarily creating commissioned public artwork, which I see as a form of applied art that I approach through the filter of material in relation to site. My tendency is to create useful sculpture for the public realm, useful places for doing nothing, that can be enjoyed bodily, structures that can be sat on, or walked on or under. I am particularly interested in inherent material attributes and how they can add enjoyment, bring pleasure, for example I am working with heat retaining terra-cotta on sculpture—making spaces that can be enjoyed into the evening, when the retained heat releases back into the bodies of those who linger and languish late in the evening.

Installation view: Elmgreen & Dragset, It’s Never Too Late to Say Sorry, Aspen Museum, 2018. Photo: Tony Prikyl

Here we speak with two contributors to zing #25 who currently share an additional curatorial crossing—Elmgreen & Dragset’s installation It’s Never Too Late to Say Sorry at Aspen Art Museum (on view through May 19th, 2019), where Heidi Zuckerman serves as CEO and Director. The work itself is a display case containing a polished aluminum megaphone on a granite pedestal, which is used daily at noon by a man to shout the phrase: “It’s never too late to say sorry!” This installation and their zing project “Variations of Blue” exemplify the combination of sculpture, installation, and performance characterizing the practice of Michael Elmgreen & Ingar Dragset, who have worked together under the name Elmgreen & Dragset since 1995. Heidi Zuckerman joined Aspen Art Museum as Nancy and Bob Magoon CEO and Director in 2005 and as Aspen Art Museum celebrates its 5th anniversary in the current Shigeru Ban building, the Crown Commons have become an architectural platform for public engagement—a context in which Elmgreen & Dragset thrive. With her zing project “…some fragment of a dream” we gain insight into what may be the beginnings of Zuckerman’s curatorial impetus, or at the least, an activation and step along the way.

Interview by Brandon Johnson

It’s Never Too Late to Say Sorry is a simple yet powerful relational gesture occurring in a public forum. How do you—both the artists and curator—feel that this work relates to its current context of Aspen, Colorado?

HZ: I am interested in Ho‘oponopono, a Hawaiian practice of forgiveness and reconciliation. There is nothing more powerful than accepting an apology that you have not, and likely will not, receive. The placement and performance of this work in front of the Aspen Art Museum, as we approach the fifth anniversary of our building, is connected to this notion.

E&D: Guilt is global—everyone has something to say sorry for. We’ve previously shown this work in cities ranging from Rotterdam to New York to Munich, and now, Aspen. A lot of influential people visit Aspen, and we hope the work prompts everyone to reflect on the potential power of an apology, whether it be related to civic issues, personal relationships, or something else entirely.

A megaphone is a very analog method of amplifying one’s voice. There are not many town criers these days. Why choose this method of communication in our contemporary context?

E&D: Today, we are bombarded by a constant stream of disembodied messages that appear on various screens in the form of tweets, text messages, news reports, emails, notifications, comments, etc. The megaphone allows the physicality of an actual human body and the sound of an actual human voice to come together and be amplified in this real-time performative action, asserting the body in space and underlining the significance of the phrase that is shouted. As you mentioned, the town crier is an extremely outdated method of communication; it starkly contrasts with all the instantaneous options we now have at our fingertips. The work harkens back to this old way of transmitting information and suggests that even though certain methods have been eclipsed by new ones, there are still some messages that endure. As an object, the megaphone is closely associated with concepts like protest, authority, disruption, and control—using it in this context hopefully brings these layered associations to the artwork as well.

HZ: I am really interested in punctuation, and the megaphone is an incredibly elegant exclamation point!!

Heidi, when did you first encounter the work of Elmgreen & Dragset, and what appealed about their practice as a curator?

HZ: While I can’t recall the first time I came across their work, two significant experiences were my visits to Prada Marfa (2005) in Texas and their Danish Pavilion installation, The Collectors, at the Venice Biennale in 2009. I am drawn to work that feels timely and relevant, and both of these installations took familiar things and offered new, surprising perspectives.

Elmgreen & Dragset’s project in zingmagazine #25 “Variations of Blue,” curated by Maureen Sullivan, focuses on the motif of a swimming pool in as documented in various installations of your work going back to 1997. What is it about pools that has kept you engaging with this subject over the years?

E&D: We’re fascinated by both the aesthetics and the social significance of pools. The idea of a private pool has in our post-war Western culture been a symbol of social status for those living in the suburbs. We first challenged this narrative at the Venice Biennale in 2009 with our work Death of a Collector, which depicted a wealthy art collector floating face-down in his pool in front of the Nordic Pavilion. More recently, our exhibition This Is How We Bite Our Tongue at the Whitechapel Gallery (2018–19) marked the first time we used a public pool in our work. That installation, entitled The Whitechapel Pool, dealt with the loss of civic space and shared values through the portrayal of an abandoned pool. We created a fictional history to accompany the pool, detailing its rise as a famed public amenity that later lost government funding and then got sold off to a private developer, who was about to turn it into a membership spa. Through our research for that show, we learned more about how the decline of public pools in the UK mirrors other cultural shifts in the past decade.

Back in 1997, one of our first sculptural works, Powerless Structures, Fig. 11, was a diving board that penetrated a panoramic windowpane at the Louisiana Museum, which is located by the sea north of Copenhagen. Inspired by David Hockney’s famous painting A Bigger Splash, the work also addressed the discourses of the late 1990s around the inclusion and exclusion of queer identities and minorities within established (art) institutions—the diving board being stuck midway between the inside and the outside of the museum. Nearly two decades later, in 2016, we began making a series of diving boards that are presented vertically and engage with the tradition of Minimal sculpture and stripe paintings. That same year, Public Art Fund presented Van Gogh’s Ear, our public sculpture of a garden pool—also displayed vertically—at Rockefeller Center in New York. It looked like the pool had been taken out of the showroom and put in this unfamiliar, urban context. The pool theme appeared again in Zero, our work for the 2018 Bangkok Art Biennale, which is a schematic interpretation of a pool reduced to its essential components, a hollow oval outline of the pool shape with a diving board and a ladder. We keep working with pools because we find them to be endlessly interesting subjects to consider on many different levels.

Spread from Heidi Zuckerman’s “. . . some fragment of a dream,” zingmagazine #25

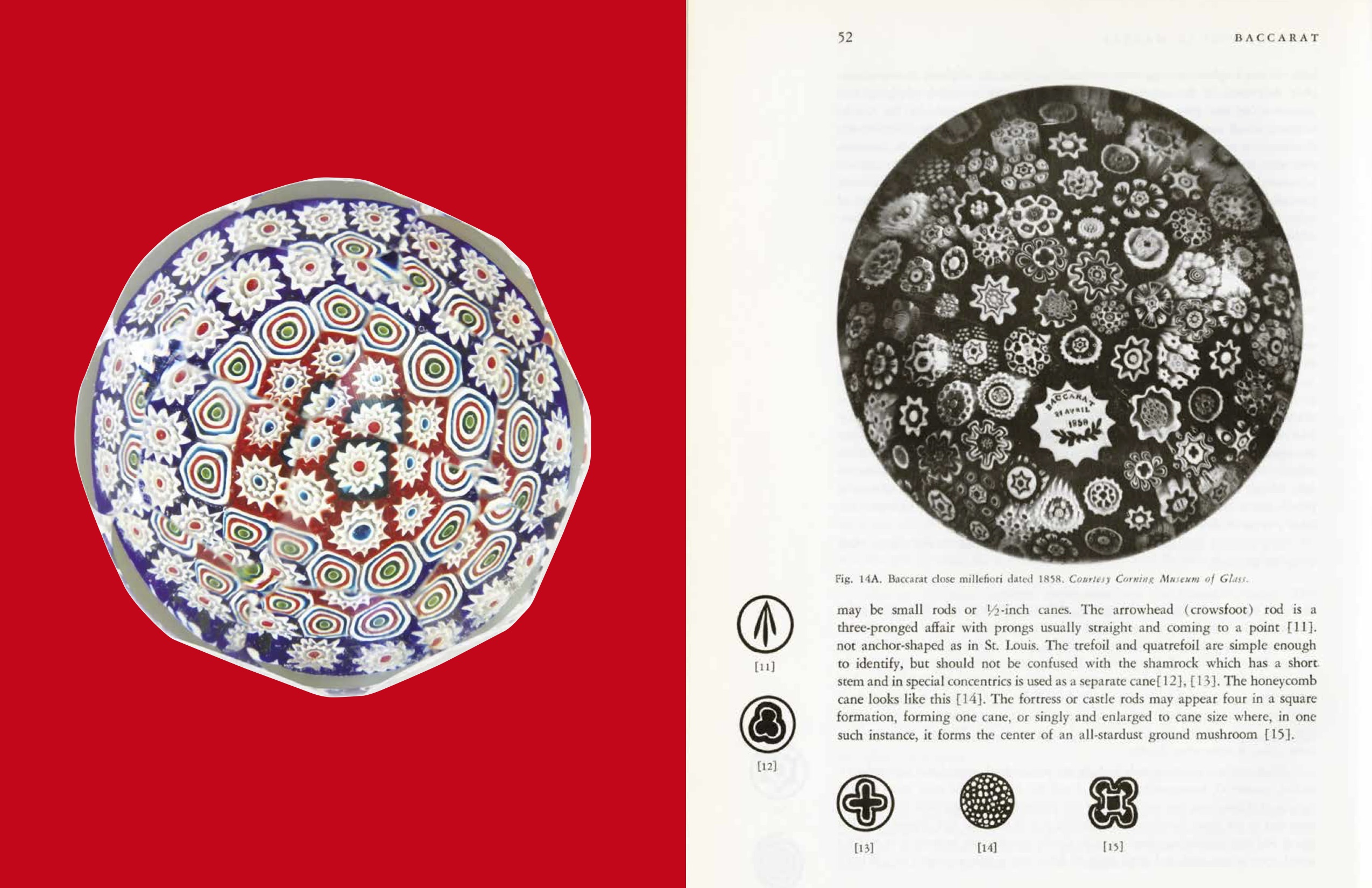

Heidi your project in zingmagazine #25 “. . . some fragment of a dream” is centered around a collection of paperweights your grandmother gifted to you. This collection became more significant after a visit to the Art Institute of Chicago, where objects like these were presented in the context of fine art. Can you further describe this satori at the Art Institute? And how have your views on collections and collecting evolved over the years (if at all)? Finally, do you still collect paperweights?

HZ: The event you are referencing happened when I was a senior in college and visiting Chicago for the first time. The satori there were linked to a much broader awakening tied to my realization that I wanted to pursue a career in art. A conversation ensued soon thereafter with my parents when I informed them of my new path. Using Joseph Campbell’s Hero’s Journey terminology, I now understand that time as my “burning of the boats” moment.

Once one catches the collecting bug, it’s virtually impossible to shake. So, yes, I still collect paperweights and, interestingly, in the last few years, people have started to gift me them as well. I also collect chairs, blue-and-white ceramics, books, shells, and, not surprisingly, contemporary art.

Finally, any forthcoming projects in the works you are particularly excited about?

HZ: The next installation on the Aspen Art Museum Commons (where Elmgreen & Dragset’s work is currently installed) is by Erika Verzutti. Verzutti will create a large-scale bronze Venus—an extension of her recent smaller sculptures incorporating organic forms that depict the Roman goddess of love, sex, beauty, and fertility. Her Venus will be inverted in a headstand. As an almost daily practitioner of yoga and a committed headstander, I am particularly excited about this upcoming project!

E&D: We have several exhibitions opening in March in Asia: two gallery solo shows and a project at Art Basel Hong Kong. We’re having our first-ever show at Kukje Gallery in Seoul, entitled Adaptations, and we’ll be presenting new works in two sections of the gallery. One section will house works that incorporate familiar elements from the public sphere, while the other will display works that focus on the human body, from abstract to semi-abstract to figurative representations of the body and some of its intimate spheres. At Massimo De Carlo Gallery in Hong Kong, our exhibition Overheated will transform the gallery into an abandoned, underground boiler room with industrial tubes of various colors and sizes crisscrossing throughout the space, along with a number of sculptural works within this basement-like environment. And at Art Basel Hong Kong, we’ll be presenting City in the Sky in the Encounters sector. It’s an imaginary city in a scaled model, installed upside-down.

After that, we’re curating a group show inspired by our favorite painter of domestic interiors, Wilhelm Hammershøi, opening at the National Gallery of Denmark in Copenhagen in April. We’re also planning a big show at the Nasher Sculpture Center in Dallas that will focus on our sculptural works, and that opens in September.

Video Still from “Disassembler”, 2018 HD video with sound

Video co-commissioned by Pioneer Works and the National Museum of Contemporary Art in Athens (EMST)

Maria Antelman is a New York-based Greek video artist and photographer. Her work focuses primarily on the relationship between humans and technology. Her project “The Spacesaver,” curated by Melanie Flood, appears in zing #25. Antelman’s solo show “Disassembler” is on view at Pioneer Works in Brooklyn until February 10th.

Interview by Natasha Przedborski

Your project “The Spacesaver” in zingmagazine uses similar imagery of eyes and hands as your current show “Disassembler” on view at Pioneer Works. What is the significance of using eyes and hands in your work?

“Spacesaver” is a series of photomontages, showing hands moving in and out of screens, touching information, specifically microfilm which is what big data used to be. In the video Disassembler, hands become one with a central system that controls them, like puppet hands. Here, rural workers hands are guided by the technical specifications of a wristband that Amazon patented for their warehouse pickers. I am thinking of hands as body parts but also as tools and as extensions of our technology How do the functions of the hand change, based on the technological evolutions? One example is how digital technology requires touching a lot of screens but at the same time touching becomes a less tactile experience as all media is digital. One touches to command rather than hold a physical object or medium like film, vinyl, printed books, etc.

In terms of the eye, we live in a panopticon economy. Surveillance and data collection are the hottest industry. At the same time, our eyes have become cameras, and we desire to capture and “share” everything we see (our social personas are the accumulation of what we have captured and shared). In my eyes, the “I” is an eye and how timeless the slicing of the eye scene from Buñuel’s film Un Chien Andalou! Our eyes or cameras produce and transmit images while at the same time these functions are recorded and analyzed by other, technical cameras and eyes. Technical vision creates this new awareness. Things and objects become smart and intelligent and their gaze is upon us. We create our technology in our image and in our likeness, and then it feels uncanny when we discover ourselves in it.

The title “Disassembler” stems from the name of the software used to transform code into a language that humans can understand. There seems to be a similar transformation that occurs when verbalizing visuals. As a non-American artist, do you feel that describing your work or translating it into English is also part of a process similar to “disassembler”?

I grew up in Athens and at the age of 18 I went to study in Madrid where nobody spoke English or any Greek. I was fully immersed and after a few years my thinking process was in Spanish, which at that moment felt like an incredible realization. Now, I have been living and working in the US for 18 years and I think of my work only in English. English is easy to work with because it has an administrative simplicity while Spanish is emotional and Greek is complex, wise, and sculptural. I am trying to maintain a multilingual situation, switching between the three languages and their different glossological idiosyncrasies.

Disassembling a language is understanding its syntax. To understand the syntax, one has to learn the grammar. When we were taught ancient Greek in school, we were given a text which we had to translate by conveying its sense (sense for sense). The syntax of ancient Greek is very dense and precise. The grammar has many rules and more exceptions, anomalous tenses, intense archaic roots and crazy compound words. Interpreting a small phrase was like deciphering a code and then magically it’s meaning made perfect sense. That process was similar to a “disassembler.” Future projects always include taking lessons of ancient Greek again.

“Disassembler” also raises important questions about how far technology can go in controlling and automating our behaviors. How do you consolidate this wish for a more organic world with the use of more technologically advanced animation methods?

Technology interprets and learns to predict our behaviors, functions and ideas. The word “organic” refers to something that has an organ (tool) that supports a living system but since synthetic organs are becoming available from biological materials, the traditional organic concept is challenged. The technological is the new nature and we are adapting organically. One of my video works in the show, The Wild West, talks about rewilding the American West by reintroducing extinct species from the distant past. It shows interiors of futuristic tech and scientific laboratories. The screen is sometimes superimposed by computer vision programming graphs, guiding the viewer’s vision and referencing machine-learning algorithms. The question is how something can be wild and designed, and how something can be controlled and become wild.

This duality between wild and controlled is eternally present in the art world. It poses the question of how something can be genuine if it is curated. As an artist, how does it feel to be making a piece with a specific audience in mind such as “Disassembler” which was commissioned by Pioneer Works?

I made my first video work (New Horizons) in 2002, without knowing what I was doing. It was wild and it still is the best video I have ever made. Ever since, I am fighting with myself not to control my process, but instead to recreate the feeling, the power and the result of the first creation. It was a genuine instinctive moment, almost mythological. With my practice, I am trying to get out of my comfort zone and take myself somewhere I have never been before. It is also a health exercise or mental workout with interesting ideas against existential anxiety and boredom. Then the work finds its audience, or the audience finds the work.

For your two pieces Darth Vader and I/Eye, what made you chose to use vintage monitors to display your work?

I think of myself as a sculptor who works with film photography and who makes electronic art works. The vintage square monitors have a body or depth as three-dimensional objects; they create a different viewing experience from the high definition flat screens with their liquid surfaces; they use an analogue aspect ratio (4/3), squarer and less widescreen. In the I/Eye, the monitor becomes the organ which supports the eye, while Darth Vader is a monolith with a head and a body. I am interested in anthropomorphic structures and representations and analogue technology is more humanoid.

Your work brings us to a different time. One that is part of the past but also deeply rooted in the future. Archives and memory are the foundation for teaching us the history of the past. In what ways do you feel like memory comes into play with your work?

During my childhood in Greece, I was only exposed to antiquities. My mother was a teacher of ancient Greek and Latin and we often visited archaeological sites. I was conceived in Delphoi. Sometimes we travelled to European cities and saw Renaissance and Baroque art and architecture. The first time I saw contemporary art was as a History and Art History student in Madrid at the Reina Sofia Museum. Years later, I landed in Silicon Valley which is a science fiction experience. I was in a new planet without any old history, or reference to the past as I understood it. It was marble versus circuits and chips. Always interested in technical things, I discovered techno archeology in an old space exploration center (AMES) and the history of Silicon Valley’s first companies with their early information systems along with other local cultural oddities. The technological memory is still exciting for me, in all forms and mediums, conceptually, historically, as digital information or analogue data and becomes a point of reference. My work is the result of all these experiences, along with the memory of my grandmother’s smell, a Greek refugee from Asia Minor.