Figure and Landscape, 2024, oil on linen, 108 x 144 inches

Juan Eduardo Gomez is a New York artist, born in Bogotá, Colombia. A longtime assistant to legendary artist Alex Katz, Gomez is dedicated to the craft of painting with his own practice— working skillfully in watercolor, acrylic, oil, and charcoal to achieve exceptional works of art. Indebted to painting in the traditional sense, his work is distinctly contemporary, seeking a direct relationship between artist, canvas, and viewer. He’s had three curatorial projects in zingmagazine: “Share” (issue #10), “Rhythm” (issue #21), and “Blow Up: Paintings by Alex Katz” (issue #22). His work is held in institutional collections, including Dikeou Collection, Museum of Fine Arts Boston, High Museum of Art, and San Antonio Art Museum, and has been exhibited at Aldrich Contemporary Art Museum, High Museum of Art, American Academy of Arts and Letters, Art In General, and most recently at James Fuentes’s new space in Tribeca in a solo show titled “Dusky Rainy Sunny,” on view through September 7.

Interview by Brandon Johnson

While I was talking to you at the opening, someone pulled out their wallet with a badge of some type. Who was that?

Oh, that was Lee Quiñones. He came out of nowhere flashing a police badge and asked me to come with him. He scared the heck out of me. The whole evening was so exciting.

How do you know Lee?

We met a long time ago, mid-’90s. My ex-wife, she was friends with many graffiti artists, and he was one of them. I used to see his work all over the place. There was a great show of Lee Quiñones at James Fuentes, that one blew my mind. I spent a lot of time with his painting. There was one at my house, a Speed Racer. I admire him. Such a great guy, a great artist.

Did you ever write graffiti?

No, not at all. But I like the approach of graffiti making, which is like direct painting. You can do it with a roller. There are many people that do it with a brush or spray paint, but it’s just the immediacy. You approach a wall and just go for it. For me, it’s kind of related to skateboarding—you need to practice. It’s very much about the physical, the movement. It’s almost athletic in a way, and it has a lot of thought behind it. It’s subversive. Rebellious.

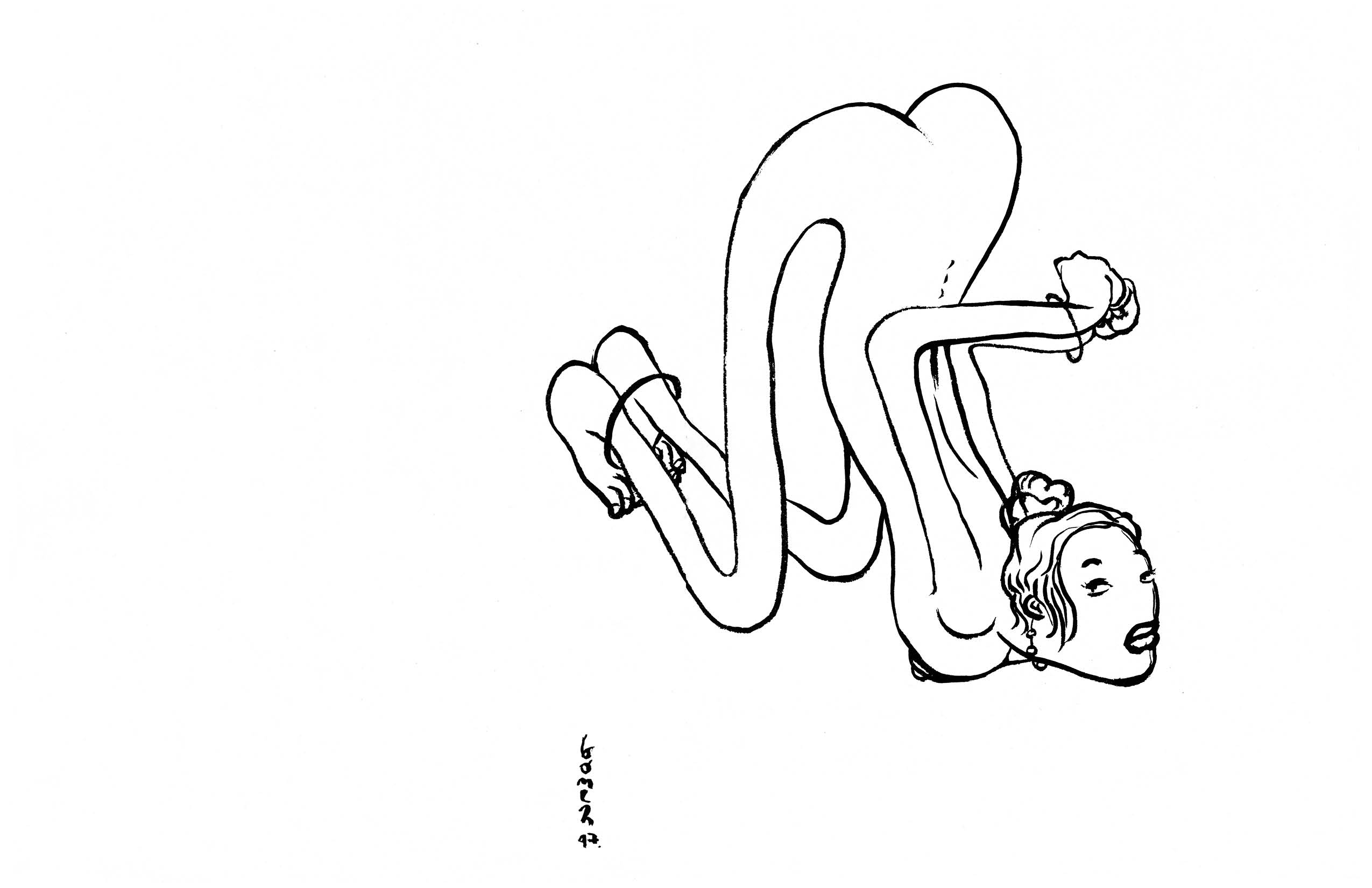

Charcoal study for Reclining Figure 1, 2024

Last time we saw you was at your studio in Navy Yard, maybe two years ago? You had a bunch of paintings, different sizes and styles on the wall, leaning against the wall, turned around facing the wall. When I walked into the show, at first the work felt very fresh and not immediately like something I’d seen during that visit. I remember the flower paintings most vividly, but then started thinking back and could see the new paintings coming out of things you’d done previously. Can you tell me from your perspective, how you arrived at these paintings?

I love painting, and I love painting big, especially. Charcoal and paper is awesome for me because I can keep producing quickly. When the pandemic hit, I was doing large charcoal drawings of human figures. Many things have happened since then, and now I’ve been noticing a sense of evolution while refining a theme. It just pops in and out, effortlessly. I picked up exactly where I left off some time ago. Even the first attempts continue to feel better than when I develop it more. And that’s great because I used to have a sense that you must do something for a long time to become good at it or to have a sense of accomplishment. But in reality, it’s like blinking, or opening a door, a window once, and going back and opening it again. It’s just there, fresh. And it’s not related to time and development. It’s more related to stepping back into it, and you’re on. Like riding a bicycle. The first time you start riding again, it feels great.

Paths that you’ve been developing over the years. For example, painting figures—it probably feels natural for you to just step back into that? You said these paintings were made over the last two months? That’s a quick turnaround.

The studio visit from James gave me a lot of energy. So, I set out to do one-to-one scale charcoal drawings of the paintings I wanted. Gardens, a lot of flowers and vegetation, from spending time upstate in nature.

I remember during our visit you were talking about gardens. You mentioned blooming morning glories in your yard or on the street in Brooklyn growing on a fence. And that your grandmother had a garden in Colombia when you were growing up?

Yeah, we were in the tropics and my grandmother was in tune with nature. My grandmother was influential. She had this thing of let’s lay down on the floor and look at the stars. Going to a flower and say, look at these flowers. Look how beautiful it was, when I was two, three years old. And she’s always pointing out things that maybe you don’t really take the time to observe. I’ll always remember her through flowers and gardens, and that feeling of looking at things and appreciating.

Reclining Figure 2, 2024, oil on linen, 132 x 84 inches

The press release from the gallery suggests you “set out to render a landscape or garden—but the human figure repeatedly appeared…” I was curious about this personification of the garden or landscape expressed as the human body. That’s very interesting, sort of a transfiguration…

Ah, you’re using my favorite word—transfiguration. Probably one of my favorite paintings is titled The Transfiguration by Raphael. I do observational work where I study things in a very academic way. I’m also sometimes thinking of something that I believe is important and try to bring it into the canvas or paper, but often I just let things happen on their own. And that’s when it gets most interesting, because I get to experience things that I didn’t know were there but they’re a main subject in my subconscious. They appear in front of me and it’s like looking at myself in a clearer way. It has a lot to do with the moment. And in these drawings the figure came and I just let it be. Then I made several drawings, and each time I increased the size of the paper, the figure expanded—the larger the paper, the larger the figure. I couldn’t fit the figure into the paper. That was the reason why they’re all cropped. That felt unique. I just thought, you know, it wants to be that way. And maybe it’s related to the landscape painting. The body becomes the landscape because it’s not synthesized or a concrete object on a background. It becomes the background and the object at the same time. At our studio visit James asked me how do I imagine a show of my work, the question lingered and helped me focus.

He asked you to consider how the work is experienced in the gallery rather than in the context of your studio?

That’s not something I always think about because I’m just focusing on each painting. I don’t care about the one before or what comes after. I’m not thinking about the paintings in space. Later James invited me to the gallery in Tribeca, which was still under construction. I stood there, and thought about large format paintings. Back at the studio I made large drawings using charcoal as if it was paint on a brush, just like an air guitar painting for me.

The paintings are very large with figures that are larger-than-life. What does it mean for these figures to be so big, taking up the entire canvas, and for somebody to be experiencing that in the gallery space?

It’s really about an immersive physical experience of inhabiting the body. It’s like you’re at a mountain experiencing the landscape and you say, I want to remember this forever. You ask someone to take a photo of you, and then you go back to the city, and realize the photo doesn’t convey the moment. It looks artificial. The scene could seem diminished, and the sense of the environment is not there.

Vertical Figure, 2024, oil on linen, 132 x 84 inches

Is the scale of the paintings tied in with the body as landscape? For example, the vertical painting of the male figure that is kind of contorted and upright. You can get lost in the different parts of this figure’s body…

The paintings are an in-person experience, it’s good to be in front of them to get the full effect. The sensation, the landscape of the body. I wanted to convey the feeling of the body, not the body in an anatomic or concrete way. Sometimes I aim to encapsulate the subject. This time I wanted the sensation. So, I allowed distortion to acknowledge feeling of the body. I wasn’t paying attention to the proper anatomical placement. Like you say, it’s much more related to the interpretation of a landscape that way. The hand, the muscle, and the experience—I’m trying to forget about the appearance and legibility.

There’s a sensuousness in these paintings that’s not necessarily erotic, but in that it’s involved with your senses, how you sense a body. Your projects in zing #10 and #21 were erotic, but I feel like there’s this line through your work of sensuousness, of a living body, a body in motion or in action, and how it can be experienced rather than like a corpse just there to be observed…

I didn’t want to glorify it or fetishize it nor denigrate it. I just wanted it to be how I was experiencing that journey through the body. The paint was helping me make that trip.

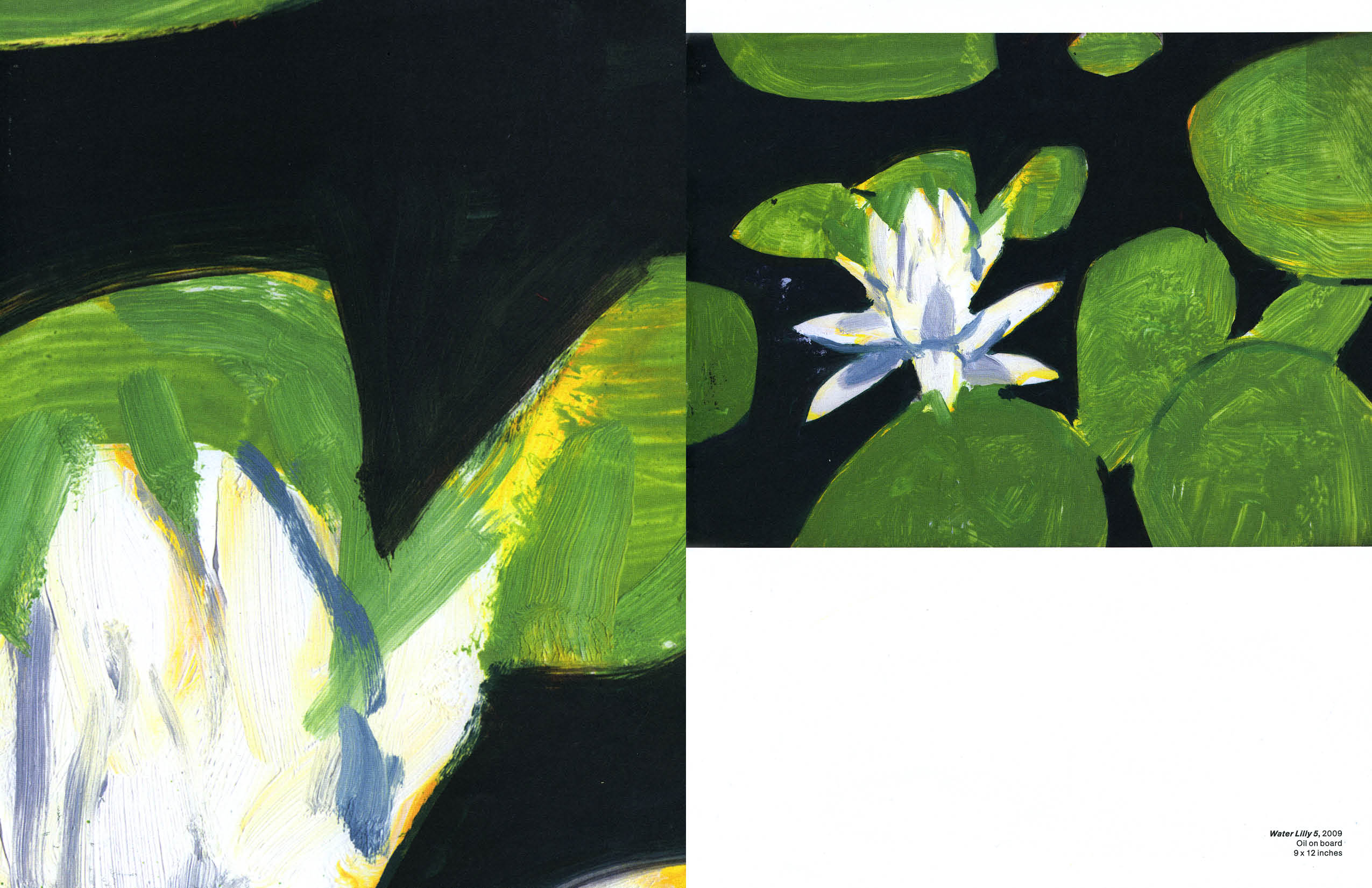

Painting from “Rhythm” zingmagazine #21

The garden is a symbol of innocence, purity, fertility, life. These characteristics are personified in your paintings with the same sensuousness of somebody like Michelangelo, often credited as an artist who understood and celebrated the body. I see some relationship there—his bodies are contorted, there are muscles, and vitality.

I think I agree with you. Michelangelo’s works are a celebration of the body. You can feel his sincere involvement with what he was doing. The David blew my mind.

When did you go there?

A long time ago. I saw The Slaves, the David. So great. There are other sculptures and paintings from the Renaissance with incredibly technical achievements, which are impressive, but they don’t have the sincerity I find in Michelangelo. His approach is personal. I feel the emotions attached to his carving. He’s completely immersed in the creation.

He was also working large. For example, the Sistine Chapel. He had to make those figures very large so people can see them from the ground. For him painting, the body’s larger than life.

Absolutely, that’s great to think about right now. How are people going to see it? How visible is it? Graffiti writers think about that too.

One detail I noticed in the show is that a flower made its way into one of the paintings. During our visit a couple years back, you showed us an amazing flower painting that was very delicate, expressive, colorful. In this show a hand holds a similar flower. Is this a nod to things that came before, things you were working on? Is this a little piece of history that made it into a painting?

Yes. Are you inside my head or what? It comes from many things coming together in one place, not one thing in particular. I never work from a single idea.

It happens on the surface?

It happens on the surface. And then I start seeing all the references, like, maybe that’s related to this occasion or that one. And that painting has many references. But someone who is special to me was having a birthday, and I forgot about it. I had a little remaining piece of linen, so I took a sharpie and I drew a hand with a flower, holding it, and I gave it to her for her birthday.

Hand and Flower, 2024, oil on linen, 96 x 72 inches

So, it came from that experience?

Not directly, but I see the reference. Another might be Tarkovsky’s film Nostalghia (1983). This guy has a candle, and he’s trying to walk a path without the candle going out. He tries to walk across with the lit candle to the end of the path he set for himself. The wind blows and he has to go back and light it up again, trying to get across. And the wind keeps blowing the candle out, like Sisyphus maybe. The flower in that painting, I’d say it has to do with the feeling of wanting to keep going. Fragility.

The flower is being held out to the viewer in a way, almost being passed to whoever’s beholding it, which I also hadn’t really thought about until now. That’s beautiful.

The painting is not necessarily about these things, but I’ll look at it like a mirror and see these references in it.

I feel like your work is criminally underrated. But James Fuentes is the perfect gallery for this show in a lot of ways, he works with serious painters who take the long view. You’re in the right company there.

James is important and Devon [Dikeou] also. So grateful.

I’m not sure I ever got the whole story on how you met Devon. Zing is down the block from Lucky Strike and she would go there all the time. That’s how you met?

I was working at Lucky Strike and she gave me an opportunity in zing. Imagine how cool that is, she looks at me as an artist. Big accent back then, even more than now. Less of a vocabulary. And just for her to say, let me see what you’re doing. That’s a huge deal.

Devon’s always done that with zing, giving opportunities to emerging artists. The drawings in issue #10 were simple, of bodies and figures.

I was mid-twenties. Those drawings were like handwriting and are actually very similar to process of making the charcoal drawings I’m doing now. I love that project.

Drawing from “Share” zingmagazine #10

One more thing I was interested in is that you studied at the Art Students League of New York, where I assume you were doing a lot with the figure?

I had a student visa. I had to be registered in school and show up full time. I was at the League, it was a very academic place. I had no stipend or anything. I was working, doing moving jobs at a trucking company. They had night classes and early classes so I could move my schedule around every week in a way that I would make the quota for my hours. And obviously, I was happy to draw and paint. And they helped me. I got a scholarship.

When did you start working for Alex Katz?

Early 2000s. I work with him where he produces paintings. I was tired of doing restaurant work and I quit. I was walking down the street in Soho and ran into Lyle Starr, a painter I know. He said that he got offered this job with Alex Katz, but he couldn’t do it. But if I was into it, I could go meet Alex and maybe I could get some work.

Spread from “Blow Up: paintings by Alex Katz” curated by Juan Eduardo Gomez, zingmagazine #22

I’m sure you’ve learned a lot from him?

A lot. Alex is an interesting guy. He’s complex. It’s been great. He’s a New York artist, the influence he’s had in the scene and the influences he had from the scene are all alive in him. And it’s been good to be around him. His approach to painting, living a life as an artist, how to be professional, production, what to prioritize, and all that has been extremely helpful. He’s been a great support. I learned about myself as an artist.

Anything else you’d like to say?

That’s all. Thank you.

Liz Hirsch and Joshua Smith at 839, Los Angeles, courtesy Jonas Hirsch

839 is a newcomer to the Los Angeles gallery scene, co-founded by writer and educator Liz Hirsch and artist Joshua Smith in their Hollywood home. Liz Hirsch is an Assistant Professor of Contemporary Art/Media Studies at Otis College of Art and Design and was the Andrew W Mellon Curatorial Fellow at Dia Art Foundation for 2016-17. Joshua Smith is an artist known for both his serial monochrome paintings and his political activism—including advocating for Frieze New York to use union labor and proposing a gun violence amendment to repeal the Second Amendment. Smith’s Untitled (Speakers), a set of stacked speakers playing a continuous loop of Roy Orbison’s “Only the Lonely” is part of Dikeou Collection. 839 will kick off its program with a group show “Summer 24” opening June 29.

Interview by Brandon Johnson

Your gallery will be joining an expanding scene of commercial spaces in Los Angeles over the last few years, including locations for many bluechip galleries from other cities around the world. Can you comment on the current Los Angeles gallery scene and how yours fits in?

LH: Well, we want to acknowledge that we’ve only lived in Los Angeles for seven years, but it feels like home to us now. It’s funny because when we moved to LA from New York we ended up renting in a corner of Hollywood that already had a few established galleries like Tanya Bonakdar, Regen Projects, and Various Small Fires. That wasn’t really intentional, but it’s been a nice aspect of the community to date and it makes our home, where we’re opening the gallery, a convenient location for people who are going out to see shows. You’re right though about the explosion of blue-chip galleries in the area recently. While it is a nice thing for the public to have more opportunities to see art and ostensibly for artists to have increased opportunities to show, it’s tragic how high baseline rents have gotten in the city and how the region is simultaneously losing working-class institutions like the 99 Cent stores, of which the Hollywood location was so famously photographed by Andreas Gursky in the 1990s.

Installation view, Summer 24, 839, Los Angeles, courtesy 839

839 will be in your home—a practice with its own lineage. Are there any home galleries past or present you’ve looked to for inspiration? And what are the idiosyncrasies and/or challenges to such an approach?

LH: There is a fascinating tradition of home galleries that have informed our approach: Alfred Steiglitz and 291, Betty Parsons, and Leo Castelli. The intimacy of the experience of seeing artwork in a home is I think so crucial. When I first met Joshua he started organizing Apartment Show with Denise Kupferschmidt, which hosted about a dozen projects, sited directly within people’s homes, mostly in Brooklyn. It was always a thrill to get to peer inside another person’s habitat and see the way a work could activate an ordinary space. Joshua had also run a gallery out of a historic duplex in the Woodbridge neighborhood of Detroit, called Commonwealth. There’s also the townhouse gallery that has been so formative. I remember going to see a David Hammons exhibition at L&M Arts uptown in Manhattan and just being blown away by both the paintings and the setting. We’ve also loved that about a place like Brussels, for example, where so many of the galleries are situated in what once would have been single family homes. Today there are exciting examples of this approach. Adam Marnie is running F out of his home in Houston. I think the biggest challenge involves the balance of the public and the private. We want to welcome visitors into our world while also maintaining a degree of privacy.

JS: And the process of converting domestic spaces into gallery spaces, let alone ones that can exist simultaneously, is a really substantial undertaking. I keep saying it’s like making French press coffee, but with your house.

Your first exhibition is a group show featuring artists mostly based in Los Angeles and New York, many of whom the gallery will represent. Is this meant to be a taste of the program? How did you find these artists?

JS: Totally. The first show will include all the gallery’s artists that we’ll be representing initially alongside a handful of others we really admire. The artists are largely culled from old friends of ours from our time in New York, where we both lived for over ten years, and from our time in LA since 2017. Two of the artists who will be in the show, Abdolreza Aminlari and Kyle Knodell (who recently moved to Berlin) went to the same art school that I did in Detroit and so I’ve been friendly with both of them for over twenty years. Nichelle Dailey is an amazing photographer based in Los Angeles who we met through her work with Lux magazine. Liz worked with another of the artists, Andrés Janacua, for a few years at Los Angeles City College, where he is a beloved studio instructor. One hope with the space and with the group show is to impress upon people that you can make your own communities or your own little worlds.

Joshua Smith, Untitled, 2021, acrylic on canvas, 45.5″ x 21.5″, courtesy the artist and 839

Joshua, we first came to know you as an artist. How does that role influence the perspective of this gallery project?

JS: My experience as an artist makes me think we’ll feel a stronger-than-usual responsibility to uplift and support 839’s artists. We feel strongly about providing our represented artists with the opportunity for repeat exhibitions, opportunities, etc. We won’t tolerate political conservatism at 839 and will maintain a safe space for outwardly progressive and left-wing artists to express themselves, which we feel is of utmost importance to the field and the wider world in this time of genocide, rising fascism, and the attendant censorship of intellectuals that accompanies both.

Clearly art of a political nature will be featured in the space. Are there any other themes to be found across the roster of artists you will be showing?

LH: The artists we’re working with are all exploring form in interesting ways. There’s a lot of abstract work among our artists. Natalie Lerner, Andrés Janacua, Olivia Gibian, Joshua, and to a certain extent the estate of Joshua Caleb Weibley, all make work that uses flat-grounded devices. We probably tend toward minimal and abstract painting and drawing. The photographers we’re working with, Nichelle Dailey and Kyle Knodell, are both kind of classic photographers in a Magnum sense. Both are concerned with people and both make work that is particularly grounded in the places they are made. The estate of Joshua Caleb Weibley represents probably our most overt conceptualist on the roster, but the brainy, humorous spirit behind the work feels a little to us like the heart and soul of the gallery. I often think our artists are artist’s artists. They all have groups of passionate followers especially among other artists.

Olivia Gibian, Untitled, 2018, watercolor, gouche, and pastel on paper, 30″ x 22″, courtesy the artist and 839

Your first solo show in September will be Olivia Gibian. I’m not finding a lot about her online. Can you tell us about her work?

JS: I think the artist Ada Friedman introduced us to Olivia and her work something like ten years ago in New York, when we all lived there. Since then, Olivia moved to LA and we did too. She makes beautiful, largely abstract paintings on paper and occasionally canvas that summon imagery of ponds, flowers, and rocks. Many of the works are made at a very intimate scale, like 5 x 7 inches. The effect is ethereal and transporting. The piece that we’re including in the first group show is a larger framed painting on paper evoking plants and water in rich tones of black, blue, and white. We had imagined that we’d predominantly be showing Olivia’s smaller paintings on paper in September, but she told us the other day that she might be crafting up something new for this show in particular. So maybe we’ll see a little combination of the two. Olivia’s also an accomplished floral designer and we’re all into the idea of uplifting this wing of her practice as well. And she’s a budding surfer! Last, we’re also in a band together called Never Work with her and her husband, Nick Earhart. Olivia plays keys and does vocals. I think people, especially artists, are going to be really excited to see Olivia’s show in September.

Darrin Alfred, photo by Eric Stephenson, courtesy of the Denver Art Museum

As Curator of Architecture and Design at Denver Art Museum, Darrin Alfred has the esteemed position of overseeing one of the largest design collections in the United States. From exquisite 18th-century French furniture to Mid-Century American classics, to rock posters of the psychedelic ‘60s and architectural drawings drafted with pinpoint precision, to say the collection is “vast and varied” would be an understatement. Alfred’s curation eloquently siphons specific points of interest from this incredible collection to create exhibitions that educate visitors about the histories and the people that designed the objects and spaces we live with and use every day. His most recent exhibition at the museum, “Biophilia: Nature Reimagined,” is a stunning example of his ability to present the diverse beauty and wonderment embodied within the design realm, and how it all stems from Mother Nature, the greatest designer of them all. “Biophilia” is on view through August 11, 2024.

Interview by Hayley Richardson

Installation view of renovated Architecture & Design Galleries, photo by James Florio Photography, courtesy of the Denver Art Museum

You became Curator of Architecture and Design at the DAM in 2007 and the department/collection has grown immensely since then, especially with the newly renovated and expanded design galleries in the museum’s Martin Building. How has your vision for the collection and curatorial approach in the galleries changed with this new space?

My vision for the Architecture and Design collection has evolved significantly since I joined the DAM in 2007. The newly renovated and significantly expanded design galleries in the Gio Ponti-designed Martin Building have been a transformative milestone for the department, allowing us to reimagine how we present and engage with design. These spaces offer a dynamic platform to showcase the breadth and diversity of our collection, emphasizing the interconnectedness of design with contemporary life and culture.

Our approach embraces a more thematic and narrative-driven format. The inaugural display, “By Design: Stories and Ideas Behind Objects,” exemplifies this shift by illustrating the abundance and versatility of design approaches across the globe. This evolving exhibition explores fundamental questions such as how design comes into being, who creates it, and for what purpose, highlighting the diverse motivations and inspirations behind objects. By showcasing works that range from handcrafted to digitally fabricated and emphasizing the social, functional, and experimental aspects of design, we aim to spark a deeper understanding and appreciation of how design shapes our lives.

Furthermore, the expanded galleries provide an opportunity to collaborate more extensively with contemporary designers, bringing their innovative works and perspectives into the museum. This allows us to present a living, evolving collection that reflects current trends and challenges in the design field. Ultimately, my vision is to make the Architecture and Design collection a vital, thought-provoking, and accessible resource that inspires and educates visitors about the transformative power of design.

DRIFT, “Meadow,” 2017, site-specific kinetic sculpture, variable dimensions, photo by James Florio Photography, courtesy of the Denver Art Museum

Your current exhibition “Biophilia: Nature Reimagined” opened last month in the museum’s Hamilton Building and it incorporates an array of work centered on creative design—from interior design and architecture, to high fashion, fine art, and smart technology. You’ve said that it’s been ten years in the making. The world is very different than it was ten years ago, as is the museum, so I am curious how the concepts and your ideas may have evolved over the last few years considering the fast-paced development inherent within the fields represented in the show.

“Biophilia: Nature Reimagined” has indeed been a project many years in the making. When I first conceived the idea ten years ago, the concept of biophilia—popularized by Edward O. Wilson—served as the foundation. Wilson’s theory posits that humans have evolved to be deeply intertwined with the natural world, and the exhibition aims to explore and celebrate that connection through the lens of contemporary architecture, art, and design.

The COVID-19 pandemic underscored the urgent need to reconnect with nature, prompting a reevaluation of the exhibition’s concepts. It was during this time that the exhibition’s three themes—Natural Analogs: Form and Pattern, Natural Systems: Processes and Phenomena, and Topophilia: People and Place—came into sharper focus, emphasizing the profound impact of nature on our well-being. Through the wisdom and beauty of the natural world, artists, designers, and architects reveal the path to reconnection, inspiring us to engage with nature for ourselves and future generations.

teamLab, “Flowers and People – A Whole Year per Hour,” 2020, Six channels, interactive digital installation, endless sound by Hideaki Takahashi, photo by James Florio Photography, courtesy of the Denver Art Museum

Living in Colorado we have the great fortune of being surrounded by spectacular natural beauty. What is your personal relationship with nature like?

My personal relationship with nature is deeply rooted in my upbringing. My parents nurtured my appreciation of the natural world from a very young age, instilling in me a deep respect for its beauty and complexity. This connection to nature has been a constant throughout my life, evolving as I moved to different places. Living in San Francisco, with its close proximity to nature’s wonders, further deepened my appreciation for the outdoors. Since relocating to Denver in 2007, I’ve found solace and inspiration in the breathtaking landscapes of Colorado and the Intermountain West. Whether hiking in the mountains or simply enjoying the local parks, I try to spend as much time as possible outdoors. Nature is not only a source of inspiration for me but also a place of solace and rejuvenation.

“Biophilia” installation view, works by Mathieu Lehanneur, photo by James Florio Photography, courtesy of the Denver Art Museum

It was recently announced that the Denver Art Museum is set to merge with the neighboring Kirkland Museum of Fine & Decorative Art, which is sure to bring a plethora of new opportunities for both museums and their patrons. What does this merger look like for your department in the future?

The Kirkland Institute at the Denver Art Museum is envisioned as a distinct department, closely linked to the existing Architecture and Design department, and poised to create synergies with other departments and collections within the museum. The Denver Art Museum now boasts one of the largest collections of design in the country, comprising something like 50,000 pieces in our joint holdings.

Each institute at DAM has its own unique character, and the Kirkland Institute brings to the table a physical facility, an established program, and an enthusiastic audience. As we continue to merge operations and integrate both museums, we look forward to sharing more detailed plans with our community. This is an exciting opportunity for growth and collaboration, and we are eager to explore the possibilities ahead.

Biophilia installation view, works by David Wiseman, photo by James Florio Photography, courtesy of the Denver Art Museum

What is coming up next for the Architecture & Design department? Do you have any projects or events you can share or allude to for 2024 or beyond?

In terms of what’s coming up next for the Architecture and Design department, we have several exciting projects planned for the remainder of 2024.

One of the highlights is an upcoming display titled Contemporary Furniture Design from Africa and Across the African Diaspora, which will be part of By Design: Stories and Ideas Behind Objects in the Martin Building’s Amanda J. Precourt Galleries on Level 2. This series of ongoing thematic installations is drawn primarily from our architecture and design collection. Africa is a vast and varied continent, and its diaspora spans the globe. Design from these various communities defies a singular narrative or aesthetic. Beyond mere functional furniture, these objects convey the richness and diversity of designers in highly individual ways. Each of these works tells an evocative story, that transcends its physical form.

We’re also working on a new display showcasing a selection of work to be gifted to the Denver Art Museum by Denver-based glass art collectors Judy and Stuart Heller. It will be located adjacent to the Reiman Bridge on the 2nd floor of the Sie Welcome Center. Glass has been used as a form of artistic expression since ancient times. The materiality of glass has been continuously transformed by artists from around the world, from the expulsion of glassmaking from Venice to the island of Murano at the beginning of the Renaissance, to the Studio Art movement which began in the United States during the 1960s. Today, contemporary glass art is an expansive field that blends historical techniques with current interests, resulting in stunning and diverse artworks.

Michael Ashkin “Here, in the desert” installation at FOYER-LA (photo: Jeff McLane)

FOYER-LA’s current project, “Here, in the desert,” unites photographs, sculptures/models, and writing by Michael Ashkin. The work grew out of Ashkin’s lifelong fascination with the New Jersey Meadowlands. Between 1993 and 2000, Ashkin wandered the area and began thinking of the Meadowlands as a site of “found gardens” where hidden struggles within our landscape revealed themselves. With this in mind, he photographed the Meadowlands and built sculptural landscape models using this source material.

Interview by Connie Walsh

I am curious about your choice to often not include humans in your images—how do you see our role as individuals or as a society with the production and transformation of space and how do we distinguish between nature and not-nature/man-made? Is that a distinction that matters to your work?

I generally don’t include humans for a number of reasons. I tend to see landscapes as themselves personified or extensions of us; even if we don’t see people, the traces of all their present and future sufferings and dreams are layered into the landscape. I have sometimes thought of this as a broader extension of Marx’s expression “dead labor.” I also don’t trust myself to photograph people properly, especially close up; I am never sure what is being expressed in the photograph and who is doing the expressing.

I don’t believe the nature/not-nature dichotomy applies. On a perceptual and epistemological level, everything is and has always been anthropomorphized—nothing natural can be represented or known in an unmediated manner. Furthermore, the human has insinuated itself into every relationship between objects on this planet; even objects that appear to be natural (say a rock) cannot exist outside the framework of human intervention. Real estate, the nation state, the park system, the threat of nuclear holocaust, pervasive post-WWII atmospheric radiation are just obvious examples. Nature exists for me but in an unknowable sense—it exists beyond our formulations and is ultimately connected to some divine logic that encompasses absolutely everything. I see my photographs and sculptures as being a place where the relationships between our provisional formulations of natural law and historical human behavior play out. These are places where we can re-envision and re-intuit based on the best of our partial knowledge.

I am also thinking about others’ descriptions of your work—“depicting marginalized, desolate landscapes.”

Everyplace is desolated (or marginalized), the question is in what way. By that I mean that there are unknowable corners and outskirts to every object.

Michael Ashkin-“Here, in the desert” installation at FOYER-LA (photo: Jeff McLane)

What makes the space seem marginalized—is it forgotten-frozen in an in-between state or moment, neither depicting an ever-changing natural state nor depicting a built state in its glory?

I agree, that it is say: forgotten, but by whom and for how long. I believe that on a deeper level, we know everything; we just need to be reminded of it.

I want to go back and look at your images from your time exploring Berlin. Somehow, I feel a sense of nostalgia, but I am not even sure what I mean by that. What do you see when looking at these images: do they represent/explore an in-between moment?

In Berlin perhaps the nostalgia you sense is, if I am lucky, the sense of history buried within the present. Of ruins no longer visible exerting their presence. At least that is what I felt when I took the pictures. The rubble, the barriers, hardened building facades, fences, and obscuring trees gave me the impression of a landscape in which forces were still struggling in seeming stillness and silence. I say seeming because the seismic forces of subterranean history persist and their coincidence can produce events that, for us, will be unexpected.

untitled images from the book There will be two of you (Fw:Books 2023)

You speak of violence—violent acts—and the idea of a haunting feeling; can you talk about this more? Who is being haunted and by what? Is it a feeling/tension you are trying to capture? Do you feel the photographs you construct expose violence/or violent acts and if so between what or whom? Is there some responsibility or evasion of and by whom?

If something is haunted, it seems to me, that means that something is being repressed. Perhaps every human decision involves some repression. Every choice involves violence to the extent that one route was taken over another. Entropy brings on a healing or scarring by means of a repressive forgetfulness. But that entropy, at least in the human world, is the result of a choice, political in nature, that is inherently violent. So the humans, their objects, and their landscapes are haunted by all past decisions.

For me, your images contain a representation of some sort of juxtaposition/struggle between nature and industrialization, but it feels almost poetic—like the two aspects/forces are trying to have a copacetic existence. Nature is reclaiming, growing out of the destruction—the industrial wasteland, trying to find a balance or a place to cohabitate.

I like that. Perhaps there are no stable objects, only forces at play, and all forces—at least how we see them—are both natural and human cultural/industrial.

Michael Ashkin-“Here, in the desert” installation at FOYER-LA (photo: Jeff McLane)

I have been thinking about Susan Stewart—the miniature and the gigantic—in terms of seeing your sculptural work adjacent to your photographic work. Somehow the models seem to feel to me as a representation of infinity/endless vast landscapes—expansive. The photographs feel intimate—even when printed large—at times claustrophobic. Which all feels a bit off kilter—thoughts on scale and your usage?

Very good question, I had never thought to compare them this way. And you are right. I know that I considered both the models and the photos to be contemporary “found gardens.” For me gardens, particularly the formal gardens of the Renaissance and the Enlightenment, tried to reveal some image of truth about the relationship between man and nature. I was consciously trying to do something similar in both bodies of work, incorporating the ghost forms (and their negations) of those historical and idealized gardens.

On the one hand, the models were constructed “found gardens” and perhaps, to achieve their truth value, the need existed to show that they were representative extracts from a much larger space. For this the miniaturization of a vast space from which a small piece was cut proved useful. The border, which I placed exactingly for the sake of proper garden proportions, still needed to feel somewhat arbitrary in a landscape of sublime extension.

On the other hand, the photographs, as enframed “found gardens,” responded to a real topography, and the sublime proliferation of their internal logic required maintaining an internal claustrophobia that I could relentlessly repeat in variation from one photograph to the next, either in the form of a very large grid (as at Documenta) or in a long “walking” sequence (as in There will be two of you). The hope was that here truth value could be obtained by the repetition of photographic extracts which appeared to be, but actually were not, arbitrary.

It’s funny you’re mentioning that the larger photos seem claustrophobic. Oddly, they do seem simultaneously both more claustrophobic and infinitely extending than when they are small. Perhaps that is because when they get larger their logic appears to expand internally as more and more details, not discernable in the smaller prints, emerge.

Are you alone? How is the experience different when it is shared? What is the “unspeakable” in your writing? Did something/someone impose an end that you write of in the book or was it a natural ending—the walking with another. I am thinking about presence and absence—both literally with a lack of human representation in your photographs and sculptures and this feeling as a viewer that I feel a part of the represented morphing—the images feel still and yet they feel almost like a film still of a larger act—development/change/deterioration/evolution.

“Am I alone?” I guess the answer would be “yes and no,” or “yes or no.” Whether one or two enter the hanger is beside the point. The sense of feeling alone stretches over my whole Meadowlands experience, but, in actuality, through a series of irretrievable and alien selves. I began walking the Meadowlands to understand them and my relationship to them. But a unity of self and experience eluded me. All I have are the fragments: the images, language, memories, and memories of memories. In the story, “There will be two of you,” which ends the book, there is the momentary promise of unity, even as it dissolves.

Michael Ashkin-“Here, in the desert” installation at FOYER-LA (photo: Jeff McLane)

You could also here talk about time—the passing of time—and your choice of how to capture it and hold it expose both your experience of time accumulating through your repetitive journeys in this landscape and the environmental effect caused by time passing. Also, the treatment or understanding of time represented in the photographic work vs. the sculptures. For me, I feel like there is a passage/movement in the photographs where the sculptures feel static—like there is a frozen event.

This is an excellent point, but so difficult to answer. If I understand you, I can answer that I am striving to escape from linear time into something approaching a more eternal awareness. And by eternity, I mean a state where the past, present, and future co-exist. Do the sculptures do this because we, the observers, move bodily and temporally in the present around a frozen moment? And maybe the photographs do that because we continue, relentlessly, to pass through a landscape of “difference within similarity” for what seems like an unending day? Relentlessness and implied infinity have always seemed integral for the truth value of my work.

Since the early 1990s, Kerri Scharlin has examined her position as both the creator and the participant of her artistic practice. Whether placing herself as the subject (and commissioner) of bodies of work like “Interview” and “Kerri’s Coloring Book” which straddle the line between fine and commercial art, or painting surreal portraits of young girls and women with seemingly prominent yet vague societal roles, Scharlin maintains a strong connection to the rich and diverse concept of the feminine. “In Her Studio,” an ongoing series since 2014 and the nexus of her project in zingmagazine issue 25, distills Scharlin’s interests in the artistic process and the ever-evolving social dynamics of the art world.

Interview by Hayley Richardson

“In Her Studio” in zing issue 25 features 16 paintings of prominent female artists in, as the title suggests, their respective studios. Is there a common thread between these artists that drew you to them?

I remember when I was a kid growing up in Miami, never feeling like what was in my general vicinity was all there was. I always needed to avail myself of ideas from books to broaden my world. I never felt like I had access to everything, I needed to feed my mind and surround myself with prompts in hopes of elevating my game.

Now, whatever happens to cross my path, if I’m drawn to it, I mark by including it in my ongoing project. There’s nothing systematic about it except that I’ve narrowed my scope to female identifying artists. It’s kind of like having a committee of good examples to remind me of qualities that I want to include in my work. Whether it’s Amy Sillman’s making and unmaking of her visible decision-making processes, Molly Zuckerman-Hartung’s wrestling her multi-directional desires into paintings, or Jessica Stockholder’s coherent forms that emerge out of the layering of divergent kinds of information, I employ their images and so many more to remind me of what not to forget.

Top: Kerri Scharlin, Jessica Stockholder in Her Studio, ink and gouache on paper, 6 in x 9 in, 2017; Bottom: Kerri Scharlin, Molly Zuckerman-Hartung, ink and gouache on paper, 6 in x 9 in, 2016

Your project statement indicates that you made these paintings out of a desire to be known and connect with these artists. Has that manifested in any way?

Since I’ve started the project, I’ve gotten to know some of the artists that I’ve included. Many I haven’t. When I had a show in 2019, a good number of the artists portrayed came either to the opening or the closing where we met. Having a public opportunity to connect with the work and those artists was wonderful, as the in-person experience is so powerful. Understandably, it can be a little awkward to introduce the project to people over social media.

Kerri Scharlin, Wangechi Mutu, oil on paper mounted onto canvas, 16 in x 20 in, 2018. Dikeou Collection

You have an appearance in another zing 25 project, “The Women’s Group: Early 1990s, New York City,” curated by Natalie Rivera. The project profiles 18 artists who engaged, socialized, and networked within The Women’s Group and how it impacted their practices during that time. It is interesting that both projects address female relationships in the arts and appear in the same issue. How has your approach to networking evolved during your career and what form does it take now?

What I’ve learned as I’ve gotten older is how necessary a connection to a community is for me. When I was younger, I felt competitive and now I rarely do. Friendships and the feeling of making this journey alongside others is a salve and in fact the thing that makes this chosen life worthwhile for me. If I hadn’t learned it already, Covid drove the point home.

Always having had the facility to make representational work that looks somewhat “accurate”, I knew that I was part of a club, I was an artist. But the question soon became what do I do with that facility and how do I shape it? What do I decide to make and what do I decide not to make? How do I narrow and organize all my impulses into a particular thing that is my mark, my signature, my contribution to the world? Only then will I potentially be part of a more exclusive Club. Or perhaps a club that I could create myself.

I didn’t just want to narrow down to a signature style but to concurrently express how it feels when the world presents so many options and the challenge of putting myself forward in a unique way. I want to show my difficulties with that exact thing and to interrogate that difficulty, that inherent vulnerability. Some people are lucky enough not to have broken parts inside of them but I’m not one of them. I want to use that uncertainty as my lens to express my perceptions, the part that is looking for certainty and for identity and for, dare I say, acceptance.

Last year you did a residency at Yaddo in Saratoga Springs and Mass MoCA. How was your experience?

Residencies are another way of broadening my circle. Last year at Yaddo and Mass MOCA, having these small temporary communities, while not always the easiest thing for the introvert in me, expanded my boundaries in ways for which I’m eternally grateful. I have seen that it can be important and even feel intimate at times.

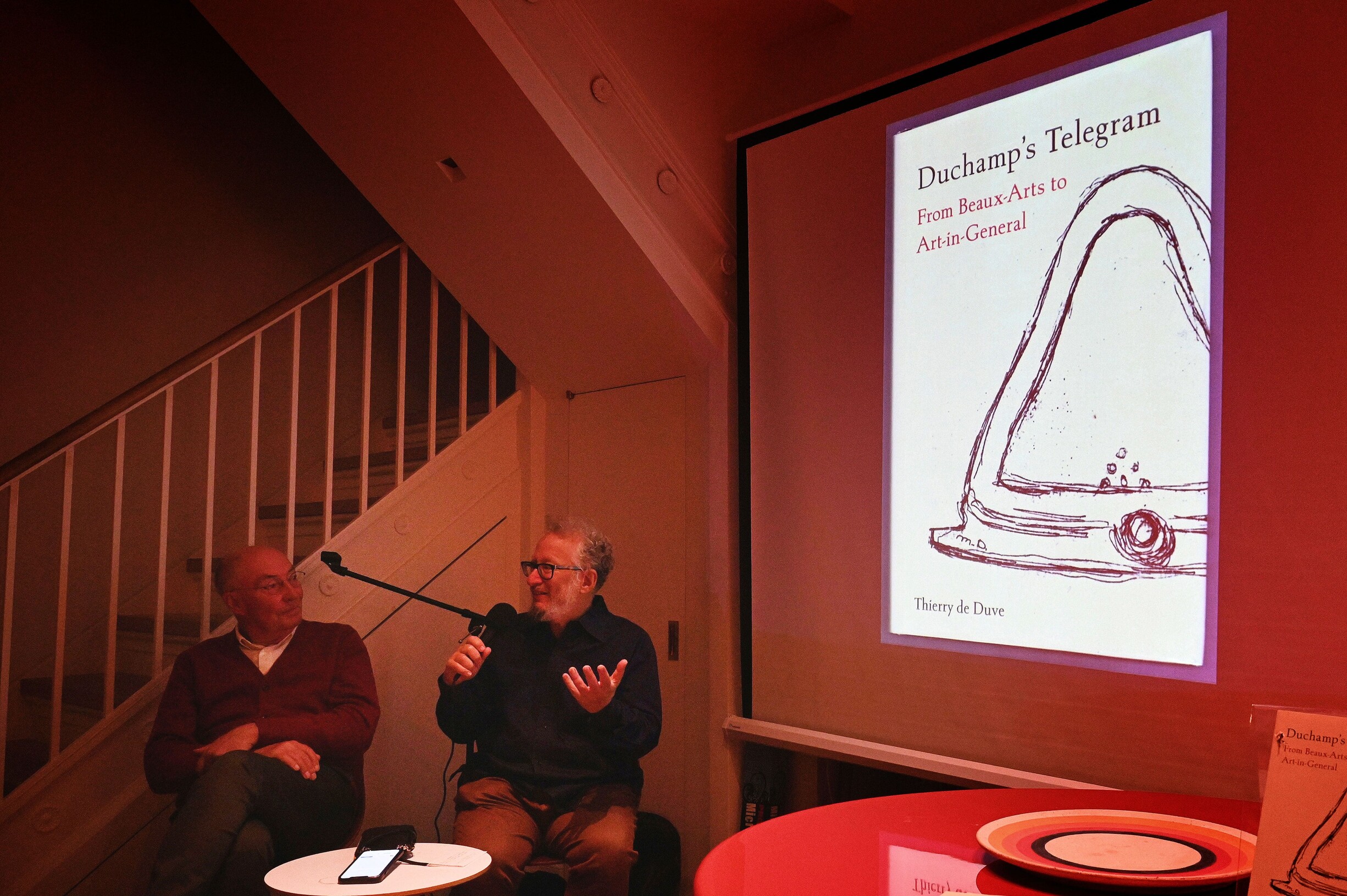

Thierry de Duve and Barry Schwabsky at Scharlin’s home salon

Salon audience

In November 2023 you hosted a conversation between Thierry de Duve and Barry Schwabsky which was published in a recent issue of Artforum. You’ve hosted such salons at your home/studio since 2016. What is the impetus/backstory of these events?

The Salons have been a way for me to surround myself in an intimate environment with friends, a sharing of goodwill with no strings attached, inviting people into my home and studio and to showcase projects in the community beyond objects: musical performances, poetry readings, book launches and discussions, performance art. I would like for them to become more frequent.

What are you working on currently? Do you have any projects or events

you’d like to plug?

Currently I’m revisiting my own images of artists to extend and complicate my compositional vocabulary. I’m using layering to find surprises that interest me. I’m also making sculptures that complement the paintings. I hope to show the work soon.