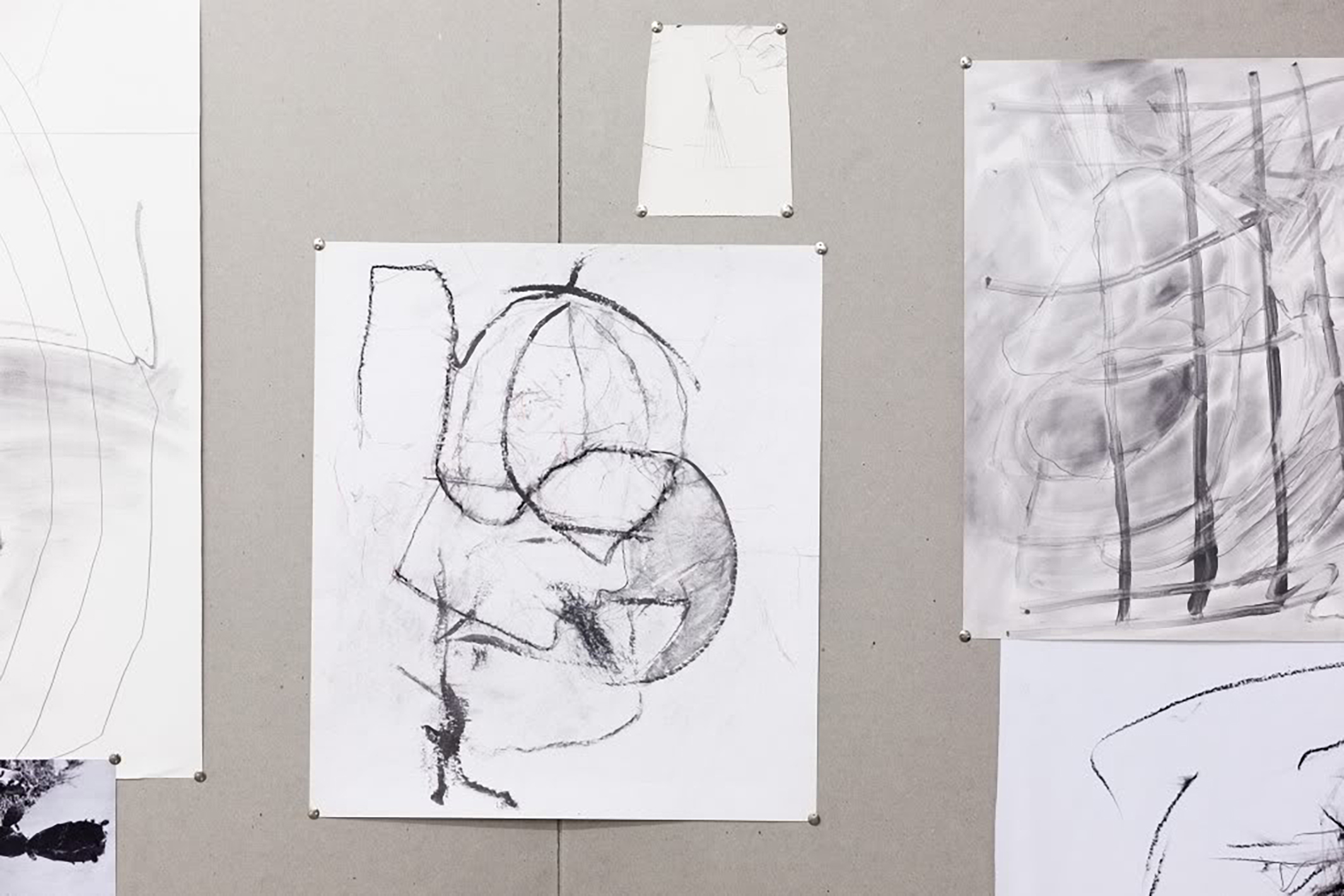

Untitled with Paperweights, 2011, mixed media, dimensions variable

J Parker Valentine’s work whispers: but her whispers exude cackles of thunder. Installations made of drawings negotiate a special place between the practices of both traditional works on paper and works of installation and object making. And in doing so they challenge the way these practices support and reinforce each other. The “drawings” are unrolled, cover one another, lean, are attached and weighed down, rest on other objects including tables—walls themselves are surfaces to be reckoned with, and drawings are even regenerated from other projects. These drawings in situ create assemblages of much larger presences that envelope, engross, charge, and frequent the space they inhabit—installing themselves in and around the viewer and the space. This flurry of quiet activity challenges gravity, loudly announcing a different language while demurely allowing for a different voice. We exchanged emails . . . Here is what transpired.

Interview by Devon Dikeou

Frank Stella’s On Painting makes a case that his “literal painting” is “pictorial”—that the physicality of the work has little to do with anything but the sum of its “pictorial” existence. Whether these aims are achieved in his work or not, I think it a useful way to approach your work. You make drawings that “literally” invade the realms of sculpture and installation, even performance. Will you speak about this . . .

I do see what he’s claiming as one way to perceive something. I’m also working in this intersection between physical form and image. For me it is often between drawn lines and the physical linear forms created by simple planar structures—for example the curve or bend in a piece of paper, or the angle of a panel. However, I’m trying to bring attention to the opposite of his case—that the physicality can’t be ignored, and a sculptural experience can and often does coincide with an image-based one. In my work, the three-dimensionality typically arises out of the process of making the drawings, more than as a point to be made.

Speaking of performance, one thing I find most interesting in your work is what you don’t show, the drawings that are hidden, the installations that seem interrupted, the gestures the viewer has to guess at, and those edited and not shown. How does this kind of performative improvisation process come about, studio to exhibition?

In the same way that frames are edited out of a film, some of my drawings are hidden. The difference is—you can see that I am hiding something from you—this is a sculptural property that creates a performative relationship between us. In the same way that I use erasure in my drawings to create an image, the blatant covering of an image with another creates yet another image. There is a recurrent push and pull of additive and subtractive processes.

The end product is often a palimpsest that reveals the evidence of time and action. Everything is improvised because the structure is based on discovery.

Untitled, 2010, metal, graphite, chalk, MDF

The materials themselves are often mined from previous works of yours and/or are recycled. This practice in turn creates a funny Nietzschian “eternal recurrence” in your work, each work exists as part of several works, both past and future. Will you speak about recurrence, eternal or otherwise, and the use of recycling as a strategy and a medium . . .

As I approach an art object as a problem, there are often many potential solutions to resolve that problem. If the artist has anything, it is the authority to make a decision on the resolution/non-resolution of a work. I am very interested in the poignancy of this decision.

When something leaves my hands, it’s finished and it’s frozen in time in its determined orientation, but if it has not yet left, I can continue to look for alternative solutions. This can be by combining it with something else. This might give the work an unfinished character—an openness to resolve, hence my interest in abstraction, which by nature, is open.

As I work on drawings, I photograph them. I collect these images in a folder on my laptop whether the works are finished or not. There is no apparent organization to this—something might be photographed once or many times in it’s process and nothing is labeled. There is really no delineation between separate works, there is no “right way up,” and the hierarchy is obscured between “good” and “bad.” This is not to say that I don’t choose particular successful drawings out of many to exhibit, but looking back at these photos and seeing how they relate from one to the next helps me to learn what a successful drawing might be.

I’m A-OK with fate. There is nothing precious with how I treat my objects. If my cat bites into a sculpture, fantastic. I often travel with a tube of rolled drawings. The edges do not stay clean, they don’t lay flat, the drawings have rubbed off onto each other and this is usually how I display them.

The way Mondrian used black & white as color—because of the sharp juxtaposition to the primary colors in his compositions—or how Impressionist palette was based on the juxtaposition of one color playing off the presence of another—is useful to think about in relation to your use of color. You use the intrinsic materials’ colors and juxtapose slight differences and nuances between and among them to create and achieve similar color connections/juxtapositions. What is the role or how do they, materials and color assemble, create, and dance through your compositions/installations?

Limiting myself to the intrinsic colors of materials allows for less “work” and thus more immediacy.

In certain ways, I think about image and color along the same lines. For example a found image of, say, a sunset, is similar to found piece of yellow fabric in the way that I do not need to draw or recreate that sunset or paint the color yellow, because they already exist. For me, drawing is not about recreating something, it is about finding something. The use of a particular image or color would most likely be due to the fact that I found it (or photographed it myself), kept it around me for a while, re-looking at it over time, and finding an importance in it, and thus a juxtaposition most likely to something I have drawn.

I’m very attracted to color brown of the mdf panels I use and the richness of graphite against it. Graphite is reflective and depending on the light or from what angle you look at a panel, it can look black against the brown, or silver and hard to see. The dichotomy between image and material is one of many in my work—the archetype being that I constantly look for form, while at the same time avoiding it.

It is as if you undertake drawing, and its intrinsic limits, and screw with all the Big Wigs that began to screw with drawing in the first place. Serra, Twombly, Tuttle make drawings by way of their final product, be it sculpture, painting, or installation, and in doing so, dismantle our traditional notion of what drawing holds. You make drawing scenarios—sculptures, installations—that use the implicit practices that drawing encompasses. At the same time you negate the essential rules associated with drawing and in the process create a new definition of drawing by way of installation and sculpture. Please give us your thoughts about this . . .

Yes, I think I do make drawing scenarios. In art school, I had no real interest in any prescribed issues, so I decided to create my own. I found that I needed constraints to work off of, and I found these in the intrinsic limits of drawing and drawing materials. Also, I have a strong interest in time-based media but wasn’t content solely dealing with the consistent technical problems of film and video and looked for more basic materials that could allow me to explore a shifting image with more flexibility.

My drawings naturally moved into the realm of sculpture when I started drawing on MDF panels. The panels had to be constantly moved around, cut down, and stacked particularly for a lack of space. The activity was physical and so were the materials. There is a sculptural property to the way I make the drawings (adding and subtracting), to the drawn images themselves, and furthermore in the presentation of them.

Untitled, 2010, detail of installation view, Supportico Lopez, Berlin

The use of found objects, like the paper weights in your work (Untitled with Paperweights) at AMOA . . . they both function literally holding down drawings and visually becoming reflective mirror orbs, compounding the space and the visual and literal implications by their presence. Luis Barragan, the Mexican architect, used mirrored orbs in a similar way. What are the architectonics of your installations and especially the found objects, like the orbs?

My structures are set up to create intersections and associations between drawings. Their relation to the architecture of the room is primarily one of support, but also to create an active viewer that necessarily has to move to see things.

The reflective mirrored paperweights acted in the same way a body of water might act in a landscape, expanding and manipulating the visual space and drawn environment. But I also chose to use them for the contrast between the near perfect reflective forms and the povera-type materials.

You also use gravity to express the architectonics, in the way you lean an MDF Board against a wall (Untitled 2010) or balance drawings on work horses (Untitled with Paperweights 2011). Can you speak about the role of gravity in your work?

I use gravity as an intrinsic material, like others that you mention earlier. It always works perfectly, its symmetrical. It’s the glue of our world.

What’s on the horizon?

Right now I’m working on a book of drawings in collaboration with Peep-Hole Milan to be published by Mousse Publishing, and a solo show next spring at Lisa Cooley.

1664 Sundays, Diana Shpungin, 2011

photo: Etienne Frossard

Diana Shpungin was born in Riga, Latvia, in what was then the Soviet Union, but has since lived in Moscow, Vienna, Rome and New York City, her current location. I caught up with her about her latest exhibition, (Untitled) Portrait of Dad (Stephan Stoyanov Gallery, May 22 – July 3 2011)—a show that was simultaneously a memorial to her deceased father, and a wider, metaphysical exploration of death.

Interview by Ashitha Nagesh

The title of your recent exhibition, (Untitled) Portrait of Dad, refers unambiguously to the portraiture work of the late Félix González-Torres. How strong would you say his influence has been upon your work?

Yes indeed, the reference was a consciously direct one to one of my favorite works, Félix González-Torres’s “Untitled (Portrait of Dad)”. I changed the placement of the parenthesis, shifting the emphasis to read “(Untitled) Portrait of Dad”. The titles of the specific works in the exhibition are all so very particular that I wanted the overarching title of the show to be more general and open ended, but also making my admiration for González-Torres known. The title, as general as it is, encompassed everything I wanted to say and reference.

The show of course is influenced by the work, life, death and “after death” of my father, but I also look at it as a respectful nod to the life and work of González-Torres. While my father had a profound influence on me personally, González-Torres had a profound affect on how I look at and approach artmaking. In a way, this show was the first time I allowed myself to really explore that correlation so directly.

I have always been an enthusiast of minimalism but González-Torres took it to a new place and fused it with the personal. He was able, with a small thoughtful gesture and with seemingly flawless decision-making, to key into a sublime something so powerful and significant. An artwork (an inanimate object) that is able to communicate a gesture that resonates with myself and so many others. His work is both personal and political, but it does not scream at you, it speaks softly, it can engage you deeply if you give it the time. It is in the subtlety of the poetic gesture where I think the strength in his work lies and brings out an empathetic quality in me that few works have before or since. It is that elusive feeling I am after with my works, that sensation, that intangible something . . .

This quote by Félix González-Torres has always resonated with me, and I often cite it when I asked why I am an artist, I especially like the “good purpose” part:

“Above all else, it is about leaving a mark that I existed: I was here. I was hungry. I was defeated. I was happy. I was sad. I was in love. I was afraid. I was hopeful. I had an idea and I had a good purpose and that’s why I made works of art.”

— Félix González-Torres

Your entire body of works, from your earlier video piece from the end of the earth to bring you my love to your most recent pieces in (Untitled), seem to be preoccupied with time and the inevitable limitations of it. González-Torres once said, “Time is something that scares me…”. How would you describe your own relationship with time? Is it something that scares or inspires you? Or both?

I am not absolutely sure if “time scares me.” Existence sometimes confuses me, but perhaps that is a comparable thing? Time is necessary, time is a given and time is enigmatic, that much I know.

But I also think time is relevant, sometimes events seem to go by so fast, other times they last what seems to be forever. I suppose when we fear something time creeps up on us more quickly. The notion of time being both so ambiguous and finite is definitely scary (especially if you think about it for too long). I think whenever you are surrounded by illness and the possibility of death; time is certainly at its scariest. This perhaps in varied ways González-Torres and I have in common.

The limitations of time stem in our great desire yet failed ability to pause and control it at our whim. I certainly have not found a way to pause time yet (other than in my work) so perhaps that is one reason why I make art and in that sense time inspires me. The work is the only place where I can at least metaphorically fuck with time. Whether that be by conceptual reference, physical process or merging time and space as video can so often poignantly do.

Your pieces explore the relationship between time and distance—focusing both on the finite and infinite aspects of both. In from the end of the earth to bring you my love, distance is a tangible, measurable thing— ‘the end of the earth’ being a physical place on the map—whilst time seems to be on a constant loop, sunrise—sunset—sunrise—sunset, and so on, all over the world. In contrast, your more recent works seem to invert this; I Especially Love You When You Are Sleeping and A Fixed Space Reserved for the Haunting, for example, highlight the limited nature of our time, along with the immeasurable possibilities of space—metaphysically speaking. What influenced this inversion? Was there a change in perspective for you?

Absolutely, the work surely encompasses time and space in varied ways; concrete physical remoteness, emotional detachment, and the intangible metaphysical void. There was no change in perspective or specific inversion between the pieces—more specifically the methods used relate to the specific conceptual content and subjects tackled within each of the works. Both are about types of longing and intangibilities, loss vs. love, the dead vs. the living etc . . .

From an ongoing series entitled “The Geographic Fates”, the dual channel video work “From The End Of The Earth To Bring You My Love” is about communication, human relationships, love, desire and the enormity of what we know and experience. I wanted to take the conventionally beautiful symbol of the sunset/sunrise and find a kind of truth in it. Two people being in two precise points, as far away as achievable from one another on earth, would still be able to communicate by ways of our natural world without the interference of technology—a sort of grand, yet simple gesture if you will.

The works in “(Untitled) Portrait of Dad” also relate to time and distance but in this instance examining ideas of death, mourning and memory. The intangibility of death is often explained by means of religion in various cultures and death is often depicted in war films or in the media as remote and impersonal, in horror films as gloomy, morose or campy. I wanted to explore this without delving into the specificity of religion, or focusing on the cold, morbid or stereotypically “dark” depictions we are familiar with and I did not want to avoid the known reality of death, glazing it over to make myself or the viewer comfortable. Instead I utilized personal familiarity, cultural mores and taboos, with a dash of the supernatural and superstitious.

The sculpture “I Especially Love You When You Are Sleeping” relates to a phrase my father spoke to me on many occasions, however I chose the phrase for the work because in an ironic manner it speaks of our inability to speak ill of the dead due to cultural appropriateness. When you are “sleeping” (or dead) I especially love you—a life is glamorized, we speak only of the good times, obituaries and eulogies seldom contain a disapproving word. We often have a selective memory of those we lose.

I am interested in what encompasses our “known” time on earth. And with the understanding that I probably will not find out more than the average human, my work is counter-productively trying to attain this knowledge anyway.

I found 1664 Sundays very interesting; it highlights the relative shortness, and the limitations of our shared experiences. Considering the personal nature of the subject, how did you feel whilst constructing this work?

The title “1664 Sundays” refers to the amount of Sundays my father and I lived in common, from my date of birth to his death. When I calculated the days, it certainly seemed like an alarmingly short amount of time. So yes, by summing it up in a succinct figure, the lack of time we have alive and/or together with another person is relatively limited, are days literally numbered. Our experiences with people can be fleeting. The memory is all that can be sustained, although that can be fractured, selective or relatively hazy.

In “1664 Sundays” the viewers receiving of the recipe bag and taking of potatoes referenced González-Torres piles and stacks. With González-Torres it is like taking from the body itself, with “1664 Sundays” the potato pile references more of a burial mound, but of living things that keep growing and have the possibility of survival. The pile becomes a memorial to a story, a shared overlap of time and experience and a particular place in history. And if one so chooses they can take the potatoes home with them and cook my father’s recipe—again counter-productively reliving an experience in a secluded intangible way. The work always maintains this peculiar condition of longing.

1664 Sundays both reduces this shared experience of time to something mundane and everyday, and simultaneously invests this ordinary object (the potato) with a deeply personal significance. In a way, it is attempting to physically represent something that goes beyond human visualization—time spent with loved ones. What does the potato signify for you? Is it a purely personal symbol of your father’s potato recipe and potato-selling on the USSR black market, or is it a wider comment on Soviet culture and its own subsequent death?

Much of my work can have varied layered, cyclical, dualistic and serendipitous connotations. I love how one object can hold several meanings, some even contradictory, some seemingly non-connected but actually linked by way of an odd coincidence or fate if you will. In this case, the personal, the art historical and the politically and geographically historical.

That being said, the potato is emblematic of a number of functions. The potato was a bonding symbol between my father and I, by way of his potato recipe he cooked for me both as a child and when I would visit him as an adult. It was the only thing I would eat that he prepared, and it was how we found common ground.

The potato also relates to my father’s story-telling (a dying act in itself) of the “old country” and of his trading fifteen tons of potatoes for his first car, a Soviet made Volga. The potato behaves as an icon of that time period of black market culture, my father used the potato akin to currency, the story indicative of a time and place far away, only directly familiar to a relative few left among the living.

And lastly, the potato had strong significance in not just Soviet times, but to this day in Russian (and much of Eastern European) culture. A diet staple often referred to as “second bread”, it has sustained many people during grain shortages in very difficult times.

Being born in a country under Soviet Rule, it was difficult to grasp the enormity of what that life was like then because of my young age. My family immigrated to the United States when I was about four years old so my memories are really based in my fathers story telling, family albums and old books we had around the home. The linkage of ideas goes through a type of hand me down translation. Again, it took me utilizing the potato recipe (a very personal ordinary thing) to get down to the inherent political significance in that common food source.

Could you explain the meaning of the chair in A Fixed Space Reserved for the Haunting? Does it have personal significance, or a wider symbolism?

I really consider my work to have both personal significance and a wider symbolism. Of course much of my work comes from deeply personal themes, but these themes are also very universal. I translate my experiences visually by finding formal elements and signifiers that may have more open ended and relatable content to others.

Regarding the personal, I am really interested in what we as a culture or society deem to be “personal” or even “too personal”. I always find it hard to really delve into a subject unless it becomes real and tangible for me. For example, I, as many, could easily glaze over and become numb to the convention within media, like the monotonous repetition of a newscast, a tragedy summed up in a CNN news crawl for example. Until a story is told in a personal empathetic way it is hard to grasp the reality of a situation.

Regarding the sculpture “A Fixed Space Reserved For The Haunting”, my father was a physician and would repair items around the home with the means of his profession—domestic objects like chairs, tables, lamps, rugs, walls and also trees in the garden.

This chair is left empty and with one leg broken signifying the lack of repair due a person’s loss. So the chair is not repaired or “fixed” as the title suggests, but rather “fixed” in space awaiting an implausible return. The chair no longer functions for the living – one would fall if they sat down and would be stained by the graphite pencil which is methodically hand coated over the entire surface. The use of graphite pencil in my work functions a bit like a ghost in itself, an impermanent medium, the prospect of erasure always evident.

Importantly, the sculpture and the title stem from one of many family superstitions of having a guest or loved one sit briefly in a chair before departing a home so they will surely return safely again. My father had me do this whenever I would visit his house. After doing some recent research I found the superstition has gone through many varied/morphed versions, but all are rooted in Eastern European culture from Pre-Christian times.

In A Fixed Space…, by blanking out the personal details from the obituaries you generalize death, which seems to contradict the rest of the exhibition, which is a very personal and specific exploration of grief. Was this your intention? Could you tell us a bit more about why you chose to do this?

Yes, underneath the chair sits a stack of New York Times obituaries with pertinent information methodically censored; -all names, dates, places etc. have been blacked out, the stack wrapped akin to a cast relating to my fathers methods in medicine. The stack although formally looks like it might be holding up the chair, is not upon closer inspection (another way of suggesting longing through the formal tension).

With the partial concealment of the obituaries, what you end up getting is this very generic, humdrum commemoration that can apply to almost anyone. Once more, yes the show is rooted in the personal, but it all speaks of the cultural ways we do or do not handle death. The chair in “A Fixed Space Reserved For The Haunting” was metaphorically made for my father, but it could certainly be related to anyone whom has passed.

Much like “I Especially Love You When You Are Sleeping”, another aspect of “A Fixed Space Reserved For The Haunting” is the notion of selective memory (or maybe just selective public sharing) when it comes to death and separation. It was worthy of noting that in all of the many hundreds if not thousands of obituaries I read, not a one had a negative word to say about any of the deceased. As a whole, I was not interested in presenting an all-out sentimental memorial of my father with this exhibition, rather simply using my experience with his death as the catalyst to getting a minute bit closer to understanding what it is that mortality and memory really is and how it functions.

Sara Veglahn is the author of Another Random Heart (Letter Machine Editions, 2009), Closed Histories (Noemi Press, 2008), and Falling Forward (Braincase, 2003). She has taught creative writing and literature at the University of Massachusetts-Amherst, the University of Denver, and Naropa University, and currently lives in Denver, Colorado.

Interview by Rachel Cole Dalamangas

In a couple of your works, I’ve noticed the recurrent theme of drowning and I think when I saw you read at Burnt Toast in Boulder a couple years ago, you mentioned something about the narrator of a prose you were working on being obsessed with “deep water.” It seems water is frequently mesmerizing, but dangerous when it appears in your proses. Given the ghostly selves that haunt the words, I can’t help but think of Narcissus. But the narrators also aren’t self-obsessive; if anything they’re masochistic, absenting, breathy—sort of like if Narcissus and Echo had had water obsessed phantom children together. How does water relate to subjectivity as this tension occurs in your work? Why the obsession with drowning?

My obsession with drowning and deep water and rivers is borne directly out of my experience growing up near the upper Mississippi River—a dangerous, swirling, mysterious, muddy place that was always claiming people. The frequency of people falling into the river and drowning, and the rather nonplussed attitude of everyone about it (“oh, someone drowned…well, anyway…”) was always so strange and troubling to me. Plus, there was the added element of my own lack of swimming skills and a very early experience in a swimming pool where I had to be rescued by the lifeguard. And I am obsessed with rivers—that river in particular, but all rivers, too. They move, They have a place to go, they don’t have a choice, they’re traversed. You have to know how to read a river in order to stay out of trouble on a boat. Currents and the way the weeds flow and wing dams and so much that’s hidden. There are people who know that part of the river as well as they know their own family—and they do use the term “read” but I suspect they may not think of it as analogus to language or fiction. It’s all very real. Especially if you end up stuck on a sandbar in a storm. On a more metaphorical and psychological level, I suppose the obsession with water, and the element of danger that is inherent in a deep, muddy river, is related to the unknown, uncertainty, all that’s hidden, and how we make sense of the unknown.

One thing that I find extremely pleasurable about reading your work is how nice the paragraphs always look on the page. They’re given all this breathing room. They’re like slices of charm cake. They contain these constellations of disparate things: peacocks, zoos, swimming pools, maps, ladies. How do paragraphs operate for you? I would say your prose feels like it goes sentence to sentence, but it’s the field of the paragraph I always remember afterward.

My unit of composition is definitely the sentence, but I’m glad to know my paragraphs offer a completeness.

You’ve done some collaborations with poets and I may be mistaken, but I believe your focus was poetry at Amherst, where you did your MFA. Why the switch to prose at DU? It’s always sort of a silly question, but one I am forever intrigued by because it doesn’t really have an answer that can be universally applied. What’s the difference, for you, between poetry and prose?

Yes, I did focus on poetry at UMass—and though I did make my attempts with lineation, the majority of the poetry I wrote during that time was prose poetry. So I was always working with and interested in the sentence. Studying and writing poetry gave me a good training in the use of juxtaposition and understatement and image and musicality, something I may have been reluctant to try in fiction had I not had the experience of working with all of those elements when making poems. For a long time I avoided prose and narrative because I thought I couldn’t do it. I only realized I could when it became clear that it didn’t have to resemble something else, and it could (and probably should) look different than, say, a New Yorker story.

Because of my background in the poetic realm, my work tends to often be classified as poetry, although I don’t think of it as such. I’m often asked to defend why what I write is fiction (‘what makes this fiction?’ many have asked me, often with a tone of ire). And while there are certainly fundamental differences between poetry and prose, I think the focus on genre tends to limit one’s reading of a work. It can be dangerous, too, to declare something fiction or nonfiction or poetry—if it doesn’t adhere to the traditional tenets of the genres, then readers tend to dismiss it as weird or difficult. And then, of course, there’s the “experimental” label, which can also be a limiting description—especially as “experiment” implies something unfinished or tossed off, something that certainly can’t or shouldn’t be taken seriously. Yet, it’s the most convenient and encompassing term—a sort of short hand—so I understand why it’s used. But it does ghettoize the work, diminishes it in way. It seems odd to me that a lot of readers resist the idea that a text arrives at the form it needs. I suppose it’s the fear of the unfamiliar. I’m not sure the other arts have this conundrum or difficulty. Perhaps it’s because the material is language as opposed to paint or notes or light. I suppose language is hard to separate as a material because we also use it to survive in the world.

There’s a lot of musicality to the prose. It’s not eccentric rhythmically; but the words echo against each other, the placement of syllables seems deliberate. The thoughts don’t always transition in content, but almost always flow euphonically. Do you have any background in music? What sort of music do you listen to and does it impact how you play with language?

I do have a background in music, albeit a limited one. Even though I studied classical music throughout my early schooling and also briefly in college, I never felt I could become good at it. But it did give me a technical background into rhythm and, I think, maybe, how one might approach simultaneity via language (an impossible task, but one I keep trying to accomplish anyway). I think I may always be subconsciously trying to evoke the kind of fleeting emotion that only music can provide—it’s so fleeting, but it’s also so imbedded (for example, I almost always wake up with a song or melody in my head). And I love all kinds of music—classical and punk and opera and old country and and strange sound collages. I tend to listen to a lot of different things, but I also can be obsessive and will listen to a particular album or song over and over. But I need complete silence to write. I am too easily distracted by melody and lyrics.

There’s a razor-sharp clarity to your work. I notice that the texture in your proses seem to do some things that are very much major aspects of realism genre and just as often, things that are the total inverse of realism. For example, like realism, there’s this extreme precision at work; and unlike realism, there’s no attempt to be naturalistic or fulfill expectations about representation. Where do these worlds you write come from? Are they dreamt? Meditated? Whispered? Listened into? Do you know them before you write them?

I never know the world before it arrives. Some are dreamed, I know, but they get transformed in the telling and in the combining, so I can’t say I lift them directly from something known, so to speak. That said, dream logic is very important and I privilege the way a remarkable event in a dream is experienced as commonplace—every thing makes sense in a dream while we’re dreaming it—it’s only upon thinking about it or telling someone else where it becomes strange, unreal, and, also, it’s when we begin to forget it. I think I’m always trying to work with that element of fleetingness and the many versions of reality we all create, dreamed or not.

So much of your work is about dreaming or dying or dreaming after dying and about a state of consciousness that is transfixed, absorbent, mid-reverie. But the prose does the opposite to me when I read: it keeps me aware that I am reading. Every word is so important. The gaps between the sentences are like precipices between thoughts. My consciousness has to stay focused. So there’s this exciting tension there of watching a dream unfold while having to keep one’s mind en pointe. Where would you place the state of consciousness that is reading? It’s not really like watching a movie, though prose narrative and film are frequently compared. Do you think of reading as being hypnotized? As dreaming?

To me, reading and writing are so similar—there’s a level of action and agency involved with both. But reading, of course, is more something that one takes in, where writing, I think, is something that one gives out. The pulling together of ideas and images, though seems quite similar on both sides.

The temporality of your works is always very strange. It’s atemporal work, I think. Or rather, there is temporality, but it’s over and gone in a fragment of a sentence. Whole histories happen in a few words. Things disappear. There’s vanishing points and things following a longing into the distance. Then it takes whole stretches of a paragraph to look through a window, to follow the flight of a wreaking ball. But there’s always a voice that is leftover that keeps interrogating, describing, cataloguing. There’s both this posture of repose and yet, when I really follow things, there is the suggestion of a terrifying idea of how the universe is arranged. What is your fascination with disappearance?

I suppose this fascination with disappearance is related, again, to the river and deep water, but also to the way in which everyone’s existence is so tenuous. The cataloguing and interrogative elements are a way to keep track, to claim space, to say, “I was here.” And time is just strange! An hour can seem like a minute or like an entire day, depending. All of this is quite terrifying to me, and I think, again, the element of organizing and keeping a space for small things that might not seem important helps to assuage the horror of the chaos of life (which I realize sounds a bit dramatic…).

What other work from you do we have to look forward to?

I recently finished a novel, The Mayflies, which has had the privilege of being excerpted in some wonderful journals. And I’m currently working on a new novel, The Ladies. While not a sequel per se, it is a related book as The Ladies were characters in the previous novel. There have also been some excerpts of this work in progress published in some wonderful places as well.

Read an excerpt from Sara’s The Ladies here: http://www.zingmagazine.com/VeglahnTheLadiesExcerpt.pdf

Joanna Howard is the author of On the Winding Stair (Boa editions, 2009) and In the Colorless Round, a chapbook with artwork by Rikki Ducornet (Noemi Press). Her work has appeared in Conjunctions, Chicago Review, Unsaid, Quarterly West, American Letters & Commentary, Fourteen Hills, Western Humanities Review, Salt Hill, Tarpaulin Sky and elsewhere. Her stories have been anthologized in PP/FF: An Anthology, Writing Online, and New Standards: The First Decade of Fiction at Fourteen Hills. She has also co-translated, with Brian Evenson, Walls by Marcel Cohen (Black Square, 2009) and, with Nick Bredie, also co-translated Cows by Frederic Boyer (Noemi, forthcoming 2011). She lives in Providence and teaches at Brown University.

Interview by Rachel Cole Dalamangas

A fair amount of your book, On the Winding Stair, is absorbed by a world of ghosts that overlays and is not-totally-invisible to the living world. Like a transparency placed on a picture. First things first: do you actually believe in ghosts and have you ever had experiences with specters and haunted houses?

I do believe in ghosts, but they fail to appear to me. I am seeking the ones I know, but they just won’t give me the time of day. Much like how the person you like the most ignores you to the bitter end. I’m much more likely to haunt than be haunted, and to wonder if I’m being seen. Also, I believe in ghosts in the way someone who is out of your life returns in another guise, or how someone who is literally dead seems to be replicated in another person who is living, in their mannerisms and gestures, even sometimes in their way of dress. These are the most powerful encounters I’ve had with ghosts, especially since the living individual does not know he is being inhabited. So it is like a private secret.

I try to avoid what gets said on the backs of books, no matter how exciting because I want an unadulterated experience of a book. In this case, I failed because I very much like the three authors who had nice things to say on the back of your book. Gary Lutz comments on your tendency toward ghosts and says something about how your characters sort themselves between “the haunters and the haunted.” I think this is keen for a number of reasons, one of which, is that “the haunters and the haunted” describes a border, or ravine separating realities in many of the stories. What or where is the border for you between a reader’s imagination and the text?

Because narrative clarity is so tenuous in my work, the reader’s imagination is pretty vital to sort out things like progression, movement, even things that probably should be pretty straight-forward such as character or location. I often think that my characters are wandering in a shifting landscape, one that is recognizable if the reader is familiar with it, but which is also dissolving in a mist. I spend a lot of time thinking about projection, how much of our lives we spend trying to make some meaningful narrative of connection out of the very few details the people around us are willing to give up. I can create an elaborate fantasy out of very little information, so it is perhaps not surprising that my fiction ends up asking the same of a reader.

A big part of the pleasure of On the Winding Stair for me is how object-heavy these stories are and how unusual (and often outdated as technologies) objects that appear are. There’s a hurdy-gurdy, a tartan blanket, an Irish mail handcar, a caravan, doubloons, a mussel trestle, a cloissonne earring in the shape of a fish, vaudeville stage acts, pyracantha, epaulets, a poster bed veil, scrims, olive linen, a cider ruin, a pink mutt, a gourd helmet and something spectacularly called a, “misery salad.” In these rich worlds, there’s a stark relation to absence and poverty—evoked in addition to ghosts—captives, bastards and “pale, hungry girls.” There’s also a damagedness, ruined beaches, suicidal Spanish gypsies. The combined imagery makes me contemplate the beauty of decay and disintegration. Are these tensions a comment or meditation on beauty for you?

I think I am often obsessed with an object which I see as distinct in its genre, much as I like a character who is both a type and an absolute aberration of said type. In the absence of an understanding of what constitutes identity, one substitutes the material details of identity: we are marked by our material trappings in so many ways. To instill objects (or even locations) with this much burden is begging for disappointment, as objects are inevitably lost, damaged or ruined, and so these objects invoke a kind of anxiety. To fixate on a type, a boxer for instance—as in the piece I am currently working on—creates a similar problem for inevitably he can’t remain totally as such (injuries are inevitable, boxers retire young), and because I am romantic, I like to dwell as much on the former thing, the former boxer. His damage is his aberration and distinction, in this case, and it calls so much critical attention to his origins.

In addition to the beauty of ruin and decadence, I can’t ignore the possibility of a social commentary that particularly reminds me of Virginia Woolf’s association in A Room of One’s Own with poverty and nourishment to the imagination (or lack thereof). In a world and an economy where most of us have to spend most of our time working (and one’s attention in what time for entertainment is leftover is often drawn to TV or the web), what time is there for reading? I admit, that’s bit dramatic of me. But, there have been periods of my life in which I didn’t have time to read or if I did, I was too exhausted to focus my attention. To ask the question more broadly: this collection seems concerned with how imagination survives in impoverishment, so how does imagination survive in a world that doesn’t value imagination for imagination’s sake (and instead prefers imagination applied to productivity, technological ingenuity, etc…)?

This issue is of genuine concern to me, and I think it comes literally from growing up poor and filling in for material lack with imagination of material decadence, hence the obsession in my work with baroque décor and artisanal niceties. I think imagination is rarely valued for anyone other than children because it is seen as impractical or naïve, but I don’t feel this way. Perhaps because I tend toward cynicism and misanthropy, I use imagination to combat these things and to draw myself back into positive contact with individuals. These days if someone tells me I have a great imagination, I assume that they are raising one eyebrow. Imagination is connected with magical thinking and psychological projection, two things that breed awkwardness in a cocktail conversation. Beyond this, imagination is attached to enthusiasm, which is doubly awkward. For all that we dismiss things that don’t earn us money, at this cultural moment, I think the fear of having an awkward moment is much more damaging.

Just as this collection is fascinated by the object world, it is also fascinated by technology (though old technology, rather than new), I think. I think too of, “The Dynamo and the Virgin,” and the world’s fascination with technology at the World Exhibition in Paris, 1900. Our (real) world is one that is perpetually fascinated by technology. And while I would most definitely not classify this work “steampunk” because it’s not (exactly) science fiction, I would suggest it grapples with a fascination with the old/vintage/antiqued and the development of technologies. How do you think the material object of “the book” will or will not change in response to technology? Is the book soon to be antiquated?

I am so tremendously flattered to have anything in my book labeled steampunk, I can barely focus on the question. I love obsolete technologies, for the same reason that I like former objects, and former character types. The book to me is always already antique, in the way that commercials are as well, because the marketing is worked into the design as artifact. Often, it seeks to trigger a past moment, and sell through nostalgia. I become nostalgic for the Old Spice commercials from the 70’s, and lo and behold, someone is already producing new retro versions of these before I even recognize the desire. Right now, there are so many book presses using retro comic or cartoon imagery, nostalgic photography, and antiqued fonts; these books are designed to look antique because it triggers our desire to own the object that is like the object from our past. It’s hard for me to imagine a movement entirely away from the book object, because there will always be those among us, no matter how reliant we become on the current technologies, who will still fetishize objects and want to possess them as such.

It seems to me too that your worlds are only possible because they’re literary—could only exist as fictions constructed of bizarre and beautiful vocabularies, although they don’t physically and logically operate too far from the margins of what we might identify as reality. There are creatures of dubious existence like mermaids and ghosts, and paradoxical, ethereal events occur. But none of these details are “absurd” in the sense that these fictional worlds are unstable. To the contrary, they seem to develop an immediate internal logic and are rather disciplined in staying true to whatever that internal logic may be. There’s a dream at work, but I am continually made aware that it is language and not experience. How important to you is it that the reader is made aware of the fact that he or she is reading, or made aware of the materiality of language?

Again, this is quite a conscious desire for me. I do believe that as writers we have chosen our medium, which is language, and should get to know it in its fluidity, its elasticity. The idea that I would try to create something in language that could be done better in film or in a visual artwork is nutz to me, although I have so many students that are going for that sort of thing. “I’m trying to write this like Frank Miller’s Sin City” they say, and they may get the flavor of the text of that work, but they fail to realize that the images of the model text were vital. I think it is fine to say I want to make something that has the effect of a graphic novel, but in language, especially if you intend to see just how to make the language do the work of image in its own right, but even that it is strange to me. I’ve just always been interested in the texture of the medium I’ve chosen.

I can never predict where a story in On the Winding Stair will end up and after reading the entire collection the stories are couched in my mind kaleidoscopically: I can’t keep them distinct, they form and reform in different patterns in my memory and I can’t locate their beginnings and endings, only their twists and tangibilities, because these stories of yours wind. Some of them seem to be able to keep going infinitely and others stop abruptly. In your writing process, how do you know when to “stop,” that is, how do you know when a story has arrived at an “ending”? What, exactly, for you, is an “ending”?

Finding an ending is the most difficult part of the writing process. For me, at this point, two things dictate endings: culmination of image, or dissipation of obsessive thought. It’s intuitive and always comes from the language. Bottom line, if I have been working with an image across a piece and it starts to feel sufficiently layered or labored, I feel I am coming to the end of something. Or, if I have had an obsessive idea or thought across the text, and it is starting to ease up, I feel I am coming to the end of something. For instance, I have an end line in which is a girl is described as “severed and refitted.” When I thought of this language, I was obsessed with it, and I wanted to find a narrative that explained to me why a girl would seem first severed, then refitted. When I had the story in mind, I worked toward the end line. Often, these obsessions of language recur later when I’m working on a new piece, and I might realize that I needed to go further in something that I’d already completed, but I am not one to go back and rework old love affairs.

Not unlike the overarching story structures, your sentences wind in a disturbing way. From the first story, “Light Carried on Air Moves Less,”: “In the center of that plain, where parched pasture grass muled, low and reedy, and sucked the humid thickness from the air till it was pinched and light and porous, a loose-ended portion of train track sat on its chalky rock pile, plank ribbed, veined with dark steel rails.” Like the warped dichotomy haunter / haunted, it seems the relationship between subject and object is mostly intact, but disturbed some. Passive objects are active (and even a bit aggressive, even if beautiful—the grass that sucks the air until it pinches), and subjects are sort of fragile, as if the train tracks are dependent and subservient to the rock pile that holds them up. What is your interest in the form of sentences?

Again, this is as much intuitive as anything. I spend a lot of time thinking about how to say something without really saying it, like trying to phrase a request to someone in which their acceptance is inevitable because it is worked into the assumptions of the language of the request, and because ultimately, I really want them to do what I want them to do. Manipulation through the medium of language. In a story like the one described above, I just wanted to overemphasize how languid and still everything was, and yet how much desire was present even in the inanimate objects, the desire to possess.

There’s a romance as well as a sense of nostalgia or grief (and even danger?) to the epigraph that gives the name to the collection: “On the winding stair / your dress rustles. / Candle burning quietly / In the dark room — / A silver hand / snuffs it out” (Georg Trakl, translated by Keith Waldrop). Trakl himself—disturbed, Bohemian, tragic, youthful—would not be out of place in the work. Did you write the collection with the Trakl poem in mind, or did you discover it later as a possible title? Given that your sentences seem to slip into the edges of poetry, how influenced or not were you by working with Trakl’s (or Keith’s?) structures?

I was hugely influenced by Trakl, especially the way a single line of his poems would often contain an entire narrative, with rich gothic elements, asylumns and castles, and these poems inevitably lead to despair and grief. I am a hopeless romantic. I was seeking a title for the collection, and kept striking out. At the time, fortunately, Keith Waldrop gave me some of his Trakl translations knowing I was a fan (of his and of Trakl). I had read an earlier version of this epigraph poem which had been translated to say “on the spiral staircase”. Of course, when I saw what Keith had done with it, I realized there was something so sophisticated and yet clear, the stair becomes active rather than the passive recipient of a common descriptor, and suddenly it said everything I wanted to say in the book.

What forthcoming works do we have to look forward to?

I’m working with an artist called Chemlawn to do something for the Kidney Press, an artist’s book in limited edition. Chemlawn does the artwork for Birkensnake magazine, and she is phenomenal, very, very strange, so I am excited to be working with her. That text is about my fixation with boxing and/or a visit to a refuge for exotic birds. I’m also trying to finish a novel, about a female filmmaker and her stable of strange actors.

Read Joanna’s Assemblage here: http://www.zingmagazine.com/joannahoward.pdf

Some time back photographer Jeronimus van Pelt contacted us about a project he was doing with welfare artist Daan Samson featuring women working in the artworld framed within a sexualized context. The photographic series features eight female curators, theorists, artists, critics, museum directors, and others who agreed to participate, working with stylist Margreeth Olsthoorn to stage the scenes. “Art Babes” debuts today as part of Torch Gallery’s booth at Art Rotterdam 2011.

Interview by Brandon Johnson

How did your collaboration come about?

Jeronimus van Pelt: A few years ago, I visited Daan Samson’s exhibition entitled “Showing One’s Colours” in TENT, the Rotterdam art centre. Almost excusing my enthusiasm, I mailed him that his work made me feel cheerful. I felt a kind of ‘direction’ in his otherwise unsettling art projects. The self-proclaimed art celebrity turned out to be surprisingly simple to approach. Almost immediately he was prepared to make an appointment in a museum in my hometown of The Hague. In the museum restaurant we ate cheese croquets with toast.

Daan Samson: There, in that restaurant, I met a photographer with an artist’s soul. Jeronimus showed me portraits of top civil servants, patricians, close friends and ministers. His shots were all characterized by splendid, sophisticated lighting. He talked comprehensively about the way in which, during his shoots, he establishes contact with the personalities in front of his camera. His stories and photos do indeed show that he manages to ‘disarm’ people.

Jeronimus: After a while, Daan raised the concept of the Art Babes. He invited me to collaborate on a photographic series within which we would give professional artistic women the opportunity to immortalize themselves as ‘sexy creatures’.

How exactly did you select your subjects?

Daan: What followed was an extensive search through the realms of emancipated art fields. We approached attractive artistic women at vernissages and art receptions. We sought models in all layers of our domain. I looked not only for artists and influential exhibition-makers, but also for vital art restorers, reviewers, and even cloakroom girls in museums. Websites such as Facebook are also very suitable channels to check photos and backgrounds. Correspondence with the potential Babes was often followed by a meeting with the artistic women in question. We spoke about sexuality, liberation, looks and lingerie.

Jeronimus: Daan regularly sent me profiles of artistic women who had agreed to give a glimpse of their most sexy side. After that I, too, sought contact with the Art Babes. Within this kind of photo project, it is important that the model and the photographer manage to get on the same wavelength before the photo shoot. I wanted to hear the voices of all the participants, in order to gauge the way in which they approached the theme.

Daan: Jeronimus is a person who relies on emotions. During the project I observed that he wished to reach some sort of communal trance. For example, in the preparatory discussions he tests the degree to which a kind of energy could be released during the shoots. During those discussions, he promotes a situation that structures this eventual trance.

Did you have to approach many women to find participants, or were your candidates generally open to the idea?

Daan: We live in confusing times. Concepts such as ‘conservative’ and ‘progressive’ seem to have become unstuck. As a result, the self-image that women have has also undergone a paradigm shift. Therefore it was not very difficult to find participants. To the Art Babes, our request probably just came at the right moment. Often the artistic girls had to admit, albeit coyly, that they found it quite flattering to be seen purely and simply as a sexy chick. Other women indicated that they were furious after reading the very first e-mail. Nevertheless, they too wished to participate, even if it was only to come to terms, once and for all, with the feminism of their youth.

Jeronimus: The Art Babe concept gives provocative commentary on our times. To me personally, it was not a goal to supply a specific male view of the concepts of sexuality and beauty. I often spoke with the models about a kind of softness that we could reveal. This softness has little to do with eroticism, it is more about a sort of energy—the softness of female energy. Recently I read an interview with the singer Antony Hegarty and I was rather impressed. I would like to explore with him, in a photographic context, what he calls the ‘softness of the cross-gender principle’. It is not clear whether Leonardo da Vinci painted the Mona Lisa with the aid of a male or female model. I experience a deep source of inspiration in this idea.

Daan: Nevertheless, the Art Babe photo series has a certain macho character. We show influential artistic women within the context of sexist role models. And it is fine that present-day women apparently have the spirit to display some of those traits now and again.

Jeronimus: Sexual clichés versus ‘lipstick feminism’ . . . it is a curious and interesting mix of impossibilities.

Is this a reaction to what can sometimes be a dogmatic intellectual insistence on political correctness, especially in the world of contemporary art?

Daan: Yes, I believe so. The masks can be dropped now, even within the world of the arts. The concept of ‘shame’ is now only for those who are actually ashamed.

Jeronimus: Both Daan and I are post-hippie children. Perhaps the Art Babe project is also a personal means of reflecting upon the feminism with which we were raised in the seventies.

Daan: And our fathers and mothers can be proud of us. We have created, with love, an attractive environment in which the Art Babes could break out of their culture-driven straitjacket. Stripped of intellectually representative expectations, the girls could emerge as seductive sex kittens.

Jeronimus: Women liberators . . . that is what we are.

Daan: Hahaha. Princess Máxima Zorreguieta will be delighted to hear that. Didn’t you make a portrait of her recently?

I’m enjoying the settings of the portraits—particularly those that suggest the artworld—Jantine surrounded by cocktails littered about at an opening, Anne sitting on crates presumably containing works of art, Eva among foam and bubble wrap in a storage setting. It’s disconcerting to see these banal work scenes become sexualized. How were these scenes selected?

Jeronimus: After pioneering work with the first two photos, we reached the conclusion that we did not want to offer true anecdotes. The energy that I like to experience in a photo is released when you offer a model the comfort of leaning upon both the fictional and the real.

Daan: With our photos we expose the true ambitions within the art scene. We allow dreamed aspirations to run wild in front of the camera. In the choice of locations and ambiences, we occasionally pounded hard on the loud pedal. And the women showed themselves to be seemingly at their ease within our décor of top hotels, smooth vodka and tasteful lofts. Fashion guru Margreeth Olsthoorn dressed all the Art Babes in creations of international fashion designers, such as Martin Margiela, Hussein Chalayan and Veronique Branquinho.

Jeronimus: Whereas I seek the power of a photo in a kind of immaterial intensity, Daan is more initiated into the world of luxury and comfort. Within his artistic calling, he pleads for a revaluation of the material. In contrast to many other artists he will not sneer at earthly possessions.

These photographs are like pin-ups to art dealers—a fantasy specific to the industry. Who is the audience for this work?

Daan: First of all, photo-lovers will be delighted by such marvelous images. Jeronimus has shot amazingly refined pictures. And the more general art collectors will also be astonished, not only by the scintillating photos but also by the Art Babes we have liberated. And finally, the less involved citizen is also welcome. We realize that there is a gap between the artworld and society. However, with this photo series we offer a hand of friendship. The most seductive Art Babes are presented on a platter.

On view at Art Rotterdam February 10-13, 2011