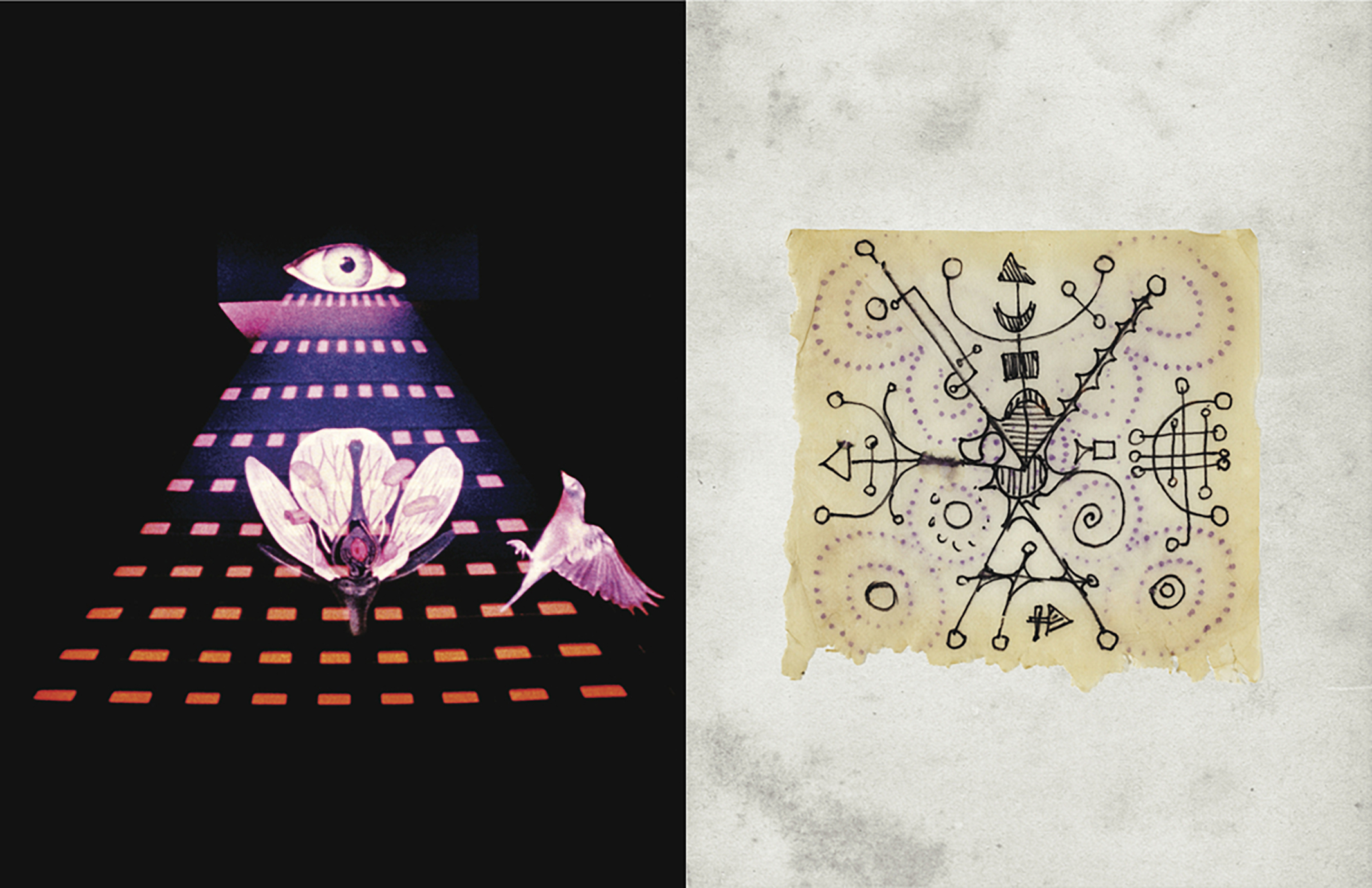

Spread from “A Strange Dream” with Still from Mirror Animations (1956-1957) on left and Untitled (c. 1977) on right

Art historian and newly appointed Dikeou Collection Director Hayley Richardson’s contribution to zing #24 “A Strange Dream” features the work of Harry Smith, a revered beat-era visual artist and experimental filmmaker, self-taught anthropologist, and explorer of esoteric knowledge. While Smith’s life’s work and interests were multi-faceted, from recording Kiowa peyote ceremonies to creating a Tarot deck for the Ordo Templi Orientis, to organizing an anthology of American folk music, his self-proclaimed primary role was that of a painter. Richardson’s past research on Smith has directed her toward this less explored (and less preserved) yet primary aspect of his work. Pulling from the collection of New York’s Anthology Film Archives, Richardson includes in her project four previously unpublished paintings and drawings among various stills from his more well-known films. “A Strange Dream” offers an entry point into the fascinating world of this cultural sage, while advocating for the primacy of his painting practice.

Interview by Brandon Johnson

You first discovered Harry Smith as an undergraduate student. Why has he stuck with you all this time, “making a racket in [your] brain ever since”?

It was a very formative time in my education, that last semester at University of New Mexico in particular. I was only taking three classes, one of which was a graduate seminar. I don’t recall how I even got into the class, but I was engrossed with the intimate, discussion-based format and how smart everyone was. At the end of the semester we presented our final projects and one girl did hers about occult and magical symbolism in the arts, and referenced this artist Harry Smith throughout her talk as a figure that was one of the last to truly understand, practice, and embed this knowledge in his work. She showed beautiful side-by-side images of alchemical Renaissance manuscripts with Harry’s abstract paintings and stills of his collage films and something just seemed to click for me, that this one artist was a conduit of sorts between the past and the future. As I progressed in my art history studies at University of Denver, I kept thinking about him and how everything he did was connected, his work in painting, drawing, film, music, spirituality, and anthropology, and it changed my way of thinking in a lot of ways. I started to see connections among the most seemingly unrelated things, which has had a tremendous impact on how I understand art and it makes many other things in my life so much more meaningful. I used the phrase “making a racket in my brain” because Harry had a bipolar personality and could be very manic/caustic, so I imagine him like this little gnome in my head getting into shit and stirring things up, reconfiguring my thought patterns.

This disparity in form is demonstrated in your project—works in different mediums stretch the boundaries of interconnectedness, but seem chosen for very specific reasons. Perhaps you could shed some light on the curatorial process—why did you choose the works that you did?

Harry had an incredible amount of artistic output, but sadly very little of it exists today. He destroyed or lost much of his art, and his landlords threw out most of it when he failed to pay rent while recording Kiowa peyote rituals in Anadarko, Oklahoma in 1964. This was an extremely distressful event in his life and marked a major downturn in his creative energy for about a decade. So part of the reason the images in my project seem disjointed is because so little is left of his artistic legacy. Some of his works exist in private collections; I am not sure how many. The rest of his paintings and drawings, of which there are about 50, as well as works on film, are housed at Anthology Film Archives in New York City. I was given a list of available digitized works from AFA and made my selections from there. I made a point of choosing works that had never been published, which are the four paintings. Although largely an “underground” figure, Harry was well known for his work as an experimental filmmaker, and the stills I chose are from his films that he was most recognized for, the main one being “Heaven and Earth Magic.” So it’s a mix of familiar imagery with some stuff that’s never been widely distributed before.

I’m particularly interested in the drawing on the torn fragment of paper. Can you speak more about how his work relates to esoteric sources? Is he working within a system of his own construction, or is the work more related on an aesthetic level?

I love that drawing as well. I saw it at AFA and I think it is drawn on a napkin, which is demonstrative of Harry’s compulsive urge to create utilizing whatever he had on hand. The drawing has a diagrammatic form, and diagrams played a major role in all of Harry’s work. When he was a young boy he would attend Native American ceremonies in the Pacific Northwest and create diagrams to correspond to the songs and dances, later he would have synesthetic experiences at jazz clubs and drew diagrams to illustrate the music, and he created elaborate diagrams while organizing and directing his films.

Diagrams are also widely used in hermetic imagery, and this particular image is like a fusion of those sources with patterns from his imagination. Similar markings also appear in the first untitled painting in the project. There is a book that came out in 1948 called The Mirror of Magic, which is a compendium of magical arts put together by Surrealist artist Kurt Seligmann. Harry was an avid book collector and I am pretty certain that he possessed this book because he seems to have pulled a lot of visual inspiration from it. In The Mirror of Magic is an illustration of celestial scripture from Athanasius Kircher’s “Oedipus Aegyptiacus” which is pretty much a hermetic alphabet composed of small circles connected with lines in various configurations. The connection between Harry’s drawing and the scripture shown in The Mirror of Magic is pretty direct, in my opinion, with Harry’s unique flourishes thrown in. Harry’s most important works have potent esoteric references, most notably his Tree of Life in the Four Worlds, which is based off the Kabbalah Tree of Life, and the album art for his Anthology of American Folk Music, which is full of that stuff, particularly Robert Fludd’s celestial monochord from 1616. His parents were Thelemites and his grandfather was a high-ranking member of the Knights Templar, and one of his earliest childhood memories was finding esoteric manuscripts in the attic of his house. He studied Kabbalah in New York under Rabbi Lionel Zirpin, was an ordained Gnostic bishop in the Ecclesia Gnostica Catholica, was a prominent figure in the New York branch of Ordo Templi Orientis, and his friends referred to him as the Paracelsus of the Chelsea Hotel. Harry’s engagement with the esoteric in his art goes beyond just aesthetics–he lived it.

Your title “A Strange Dream” is very apt for this selection. Does it derive from a specific source?

“A Strange Dream” is the name of Harry’s very first film, which he created by painting directly on the film circa 1946-1948. He started making these films when he was first introduced to jazz and wanted to illustrate the music. This particular film was originally intended to go with the music to Dizzy Gillespie’s “Manteca,” which he also made a painting after but no longer exists. If you play the song and video at the same time they synch really well. I think it’s a good title to introduce the project, as it is pretty strange and dreamy, and seems an appropriate description for Harry’s life in general.

Have you done any other work/projects involving Harry Smith?

I wrote my master’s thesis about Harry’s paintings. There is a lot of information out there about his work in film and music, and people would reference his paintings with admiration but no real academic research had been applied to them. He even said his “primary occupation” was as a painter, so it seemed like a necessary area to investigate further.

Interesting that he would say his primary occupation was painting, especially since he seemed to have destroyed many of his own paintings and was involved in so many other fields. Do you have any further insight onto why he would consider himself as such?

It was in a 1965 interview with film historian P. Adams Sitney when Harry said, “I was mainly a painter. The films are minor accessories to my paintings; it just happened that I had my films with me when everything else was destroyed. My paintings were infinitely better than my films because much more time was spent on them.” (http://www.ubu.com/sound/smith_h.html)

Yes, he did destroy, give away, or abandon some paintings, but it was in 1964 that his landlords trashed everything, except the films which he had with him or had already given to Jonas Mekas at Anthology or Allen Ginsberg for safe keeping. He went to the Fresh Kills landfill everyday to look for them. Harry started painting at a young age; he painted directly on film, and made paintings to map out the complex projection schemes for his films. Painting was the generative activity for his creative pursuits in other media.

Any plans for future Harry Smith curatorial projects?

I’d like to get my research published somewhere, just haven’t had the time to do that. It would also be a real treat to present a screening of his films with a live jazz band to provide the soundtrack. Perhaps someday at Dikeou Collection . . .

Speaking of which, you recently took over as Director of the Dikeou Collection. What can we expect there moving forward?

I started as an intern at Dikeou Collection in 2011 and am honored to be the new Director. I have learned so much and seen the collection grow immensely over the years. My main priority is maintaining the upward momentum with programming, community engagement, and exhibitions. Nothing has been formally announced yet so I won’t say too much, but there are some big projects in the works for 2016 and 2017. The collection has been open to the public for 13 years, and with the current projects we have on the table I see that we’re transitioning from a period of establishment and growth into building a real legacy, so I am hoping to introduce some new concepts that can be carried on long-term.

Simon Bill seated in front of his signature oval paintings. Image courtesy of the artist.

English painter Simon Bill has a reputation as an “artist’s artist.” His work, which consists almost exclusively of large oval paintings on MDF board, is collected by a loyal base of fellow British artists who see the depth of consciousness and humor embedded within their often grimy surfaces composed of corn kernels, leaves, and floor varnish. The ovals are like portals into the infinite curiosity and complexity of Bill’s mind in which he pushes himself to make each one completely unlike any other that he made before. These works spring from a psychological interest in visual perception, a field he has studied in depth academically.

In zingmagazine 24, Bill flexes his skills as a writer with a short-story titled “How a Man Schall Be Armyed” about an artist who invests a good deal of money on a custom suit of armor and wears for the first time to a private viewing at a gallery. Bill’s writing integrates such an illogical scenario with real life situations and outcomes so seamlessly that it seems like he wrote this story based off personal experience. I even had to double-check to confirm that it was fiction. Bill’s psychological understanding of perception comes through in his writing and visual art, giving him the ability to convince his reader/viewer of the veracity behind the most outlandish of his creations.

Interview by Hayley Richardson

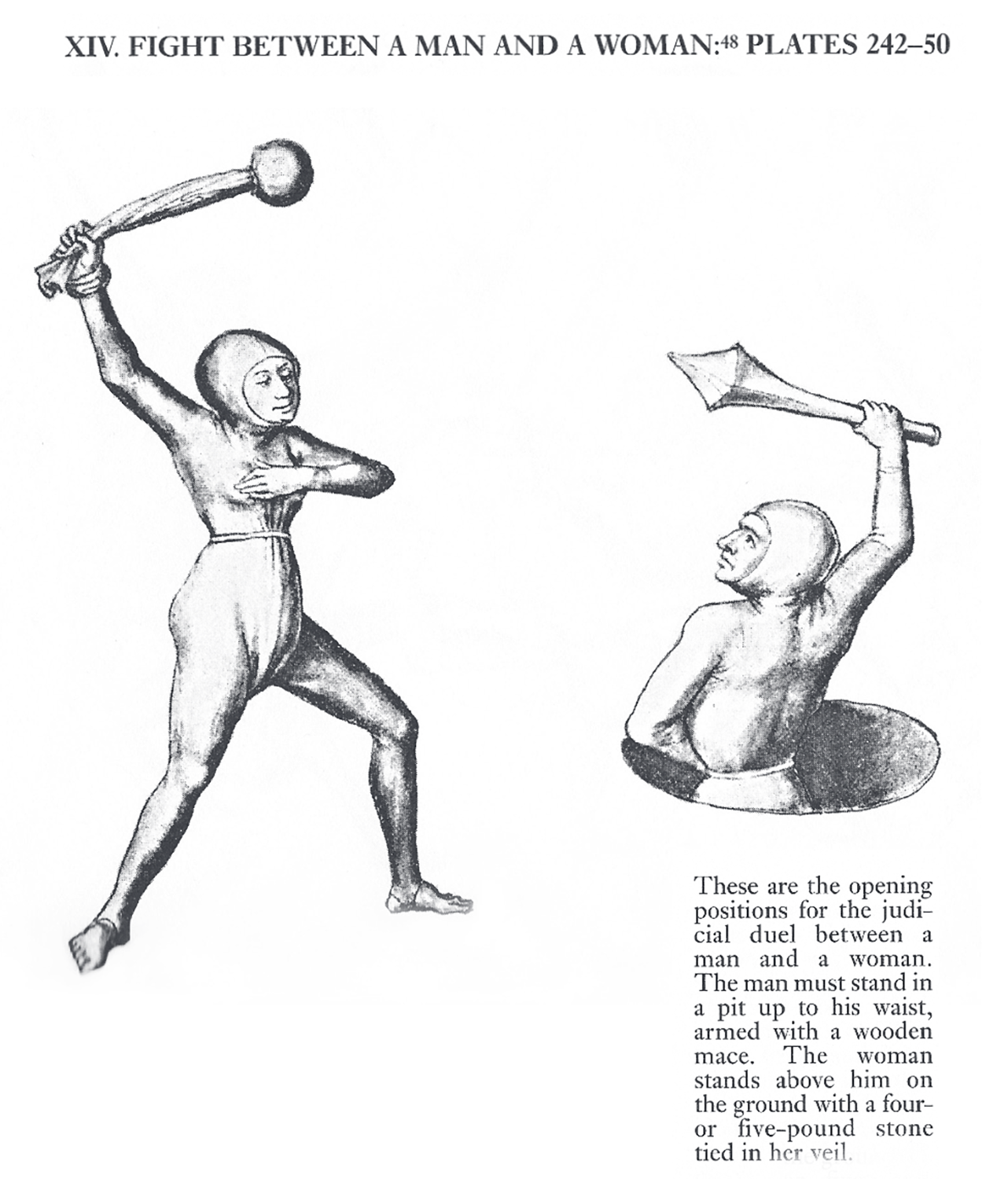

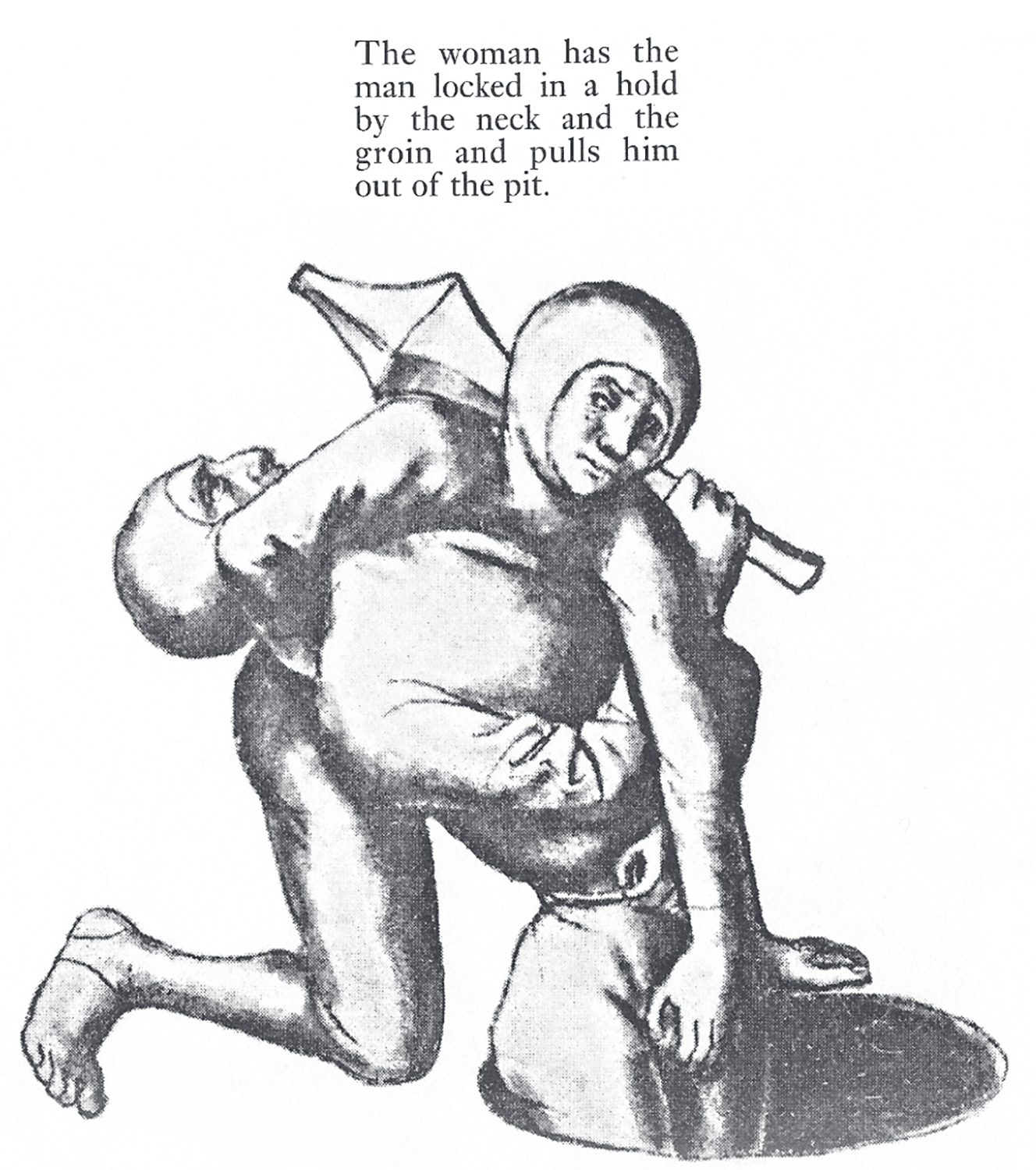

Your project in zingmagazine 24 is a fictional short story that is hilarious and absurd yet written in a very believable manner. The accompanying images are also funny in this context but relevant and interesting for their obscure historical value. Can you share some footnotes to this story and how you came up with it? Did the pictures inspire the text in some way?

I attached those pictures to the text especially for this ZING publication of it (it has been published once before, years ago, in an anthology called FROZEN TEARS 2003—pub. Article Press, ed. John Russell). But they are of course connected. The suit of armour described in the story is roughly contemporaneous with the pictures. They come from one of the German ‘fechtbucher’ (fight books) of the mid 15th century—basically martial arts manuals. And I chose them because they are so odd. They show a judicial duel between a man and a woman. The loser gets put to death, or they do if they haven’t been killed already in the fight.

This short story was my first real go at writing fiction. What gave me the idea was an event at which a battle from the Wars of the Roses was reenacted, and afterwards I saw a man in full armour coming out of one those portable toilets. That prompted, more or less naturally, some speculation about all the other contemporary things you could do whilst dressed like that. And since I am an artist, and have at times felt that I was doing almost nothing but go to private views, I wrote it about that.

The theme of the improbability of some actual things, like, for instance, the art world, is something that crops up regularly in my fiction. I am very interested in the strangeness of real things (and I find the weirdness of invented or fantastical worlds completely pointless). The terrific implausibility of these real things, which tends not to be evident to those of us who are involved in them, is made salient by having two such things in one context; one story—here it’s medieval reenacting as a hobby, and the contemporary art world.

A page from Simon Bill’s project, “How a Man Schall Be Armyed,” in zingmagazine issue 24. Drawings are reproductions from 15th century originals by an unknown artist commissioned by Hans Talhoffer.

A 2004 article from Modern Painters says that the first art show you ever saw was Arms & Armour at the Wallace Collection in 1964. I can’t help but wonder if that experience has any connection with How a Man Schall Be Armyed and your interest in medieval European combat. Were you always interested in art and history growing up?

I have been interested in a great many extremely diverse subjects over the years, and those have been two. Others include neuroscience, BIBA (the shop), philosophy, comedy (I used to collect records by e.g. Bob Newhart, Lenny Bruce, Monty Python), swords, music (Bach and the Butthole Surfers, and I’m very interested in the shoegazing revival), and cooking. And other things . . .

Like in How a Man Schall Be Armyed, your book Brains (2011) also features an anonymous artist as the narrator/main character. Is this individual, in either story, sort of an amalgamation of various personalities from the art world, or reflect aspects of your own personality?

I know some writers of fiction claim that their characters, once created, are self determining, so that the author magically loses control, but if that were true more characters in books would just sit around eating pistachio nuts.

All the characters in my book (with the exception of some very minor ones) are amalgams or composites with various sources. They are drawn from other people and myself, plus a great deal about them is, of course, made up—it’s fiction.

The central character of a book is the one least free to be, as it were, themselves, because they are the character most obliged to do what the book needs them to. The unnamed protagonist of BRAINS has a set of characteristics I find funny or interesting, and is seen bringing those characteristics to a series of situations which I also find funny or interesting. It’s not meant to be naturalistic in any stylistic way, but as it happens that is more or less the way actual characters, real people that is, are formed. We are dealt a hand, somehow, and then we play it.

Lucky Jim, installation view, BALTIC Centre for Contemporary Art, 2014. Image courtesy of the museum.

Last year your solo exhibition, Lucky Jim, at the Baltic Art Center featured more than thirty of your oval paintings from 1999 to 2014. Every piece is composed with different materials and in varying styles, the only consistency being the shape of the canvas. Is there an underlying subject matter or theme that unifies these works?

As soon as I spot a characteristic common to all my oval paintings I do one that doesn’t have it. The point is to do a potentially infinite series with no one thing in common, so, in the context of the whole body of work, what gives each work its identity is just the fact of it not being any of the others. The paintings are defined negatively. This means you can’t have a typical example of my work. And this may be why so few collectors ever buy them. I didn’t think that through very well, did I.

A lot of those paintings have suffered a weird fate. The dealer who represented me, a guy in LA called Patrick Painter, has gone insane, and has put about sixty of them in a storage place in Compton. He wouldn’t even release them for the BALTIC show. I’m expecting to see my work on Storage Wars any day.

I read that you are currently pursuing a PhD on art and the neuropsychology of visual perception. Has research in this field influenced your own art or changed the way you experience it?

It hasn’t changed my art or changed the way I experience it. But I want to better understand how I experience it. There has been a thread within art theory that brought the psychology of visual perception to bear upon the understanding of art. I’m thinking especially of Rudolf Arnheim. Art theorists have forgotten about this, because of their strong emphasis on ‘Critical Theory’ and a culture critical approach. I reckon they are really missing out. The neuropsychology of visual perception has come on in leaps and bounds since Arnheim, and art theory folk have just ignored it. Too sciencey I guess.

Art, writing, and neurological studies all tie together in your practice. Do you have a specific goal in combining all these pursuits? Does one area serve as the dominating or guiding force in this scheme?

I’m an old fashioned polymath.

These days images seem to be superseding words as our primary form of communication. In that same article from Modern Painters you state, “language is slow to adapt to developments in art,” that “writers are stuck for words.” Being both a writer and an artist, do you often find yourself faced with this conundrum? Does criticism of contemporary art have value if its language is supposedly inadequate?

I haven’t got a primary form of communication because they are each good at doing different things. This is why I have no time for those mock innovations in contemporary art that consist only of replacing an existing medium with another one that already existed elsewhere in our culture. So, for example, ‘text based’ art is no innovation because, surprise surprise, people were already writing things down anyhow before artists came along and decided it was a new art form.

And there’s ‘time based’ art isn’t there. A characteristic unique to visual art has been that, while the other creative media such as music, literature and theatre, were all time based, painting and sculpture were not. So making visual art ‘time based’ adds nothing we didn’t have plenty of already. It’s actually a net loss.

You are often associated with the Young British Artists. Do you still feel an affinity with this movement/group?

We have very little in common as artists, but I do know a lot of them. That’s the whole of the association with them really. We have been in the same rooms as each other, sometimes. Plus my daughter and Gavin Turk’s daughter are best friends.

A page from Simon Bill’s project, “How a Man Schall Be Armyed,” in zingmagazine issue 24. Drawings are reproductions from 15th century originals by an unknown artist commissioned by Hans Talhoffer.

What are some of your favorite galleries/museums/art venues? Any recent exhibitions that really caught your attention?

I love museums, although they have all been done up in recent years, so there aren’t many with that neglected, spooky, feel I used to enjoy. Most of the ones I know well are in London, but the Metropolitan in New York is amazing. You mentioned the Wallace Collection, and that’s still a favourite. The Imperial War Museum (I often think contemporary artists need to look at more things other than contemporary art). The Barbican, near where I live, has OK art shows and an amazing library. The V&A is great. In fact all the main ones in London, The British Museum, The Natural History Museum and the Science Museum, are all great. I would also recommend The Royal Armouries in Leeds, and the BALTIC centre for contemporary art in Gateshead. My friend Brian Griffiths has a good show on there now. The Museum of London has a display of knapped flints I really like.

Do you have any upcoming shows or projects you can share?

My novel ARTIST IN RESIDENCE comes out in May 2016 (published by Sort of Books and distributed by Faber). I’m planning a painting show to coincide with that. Not oval paintings. They will be miniatures, painted in oil, on copper plates the size of a credit card.

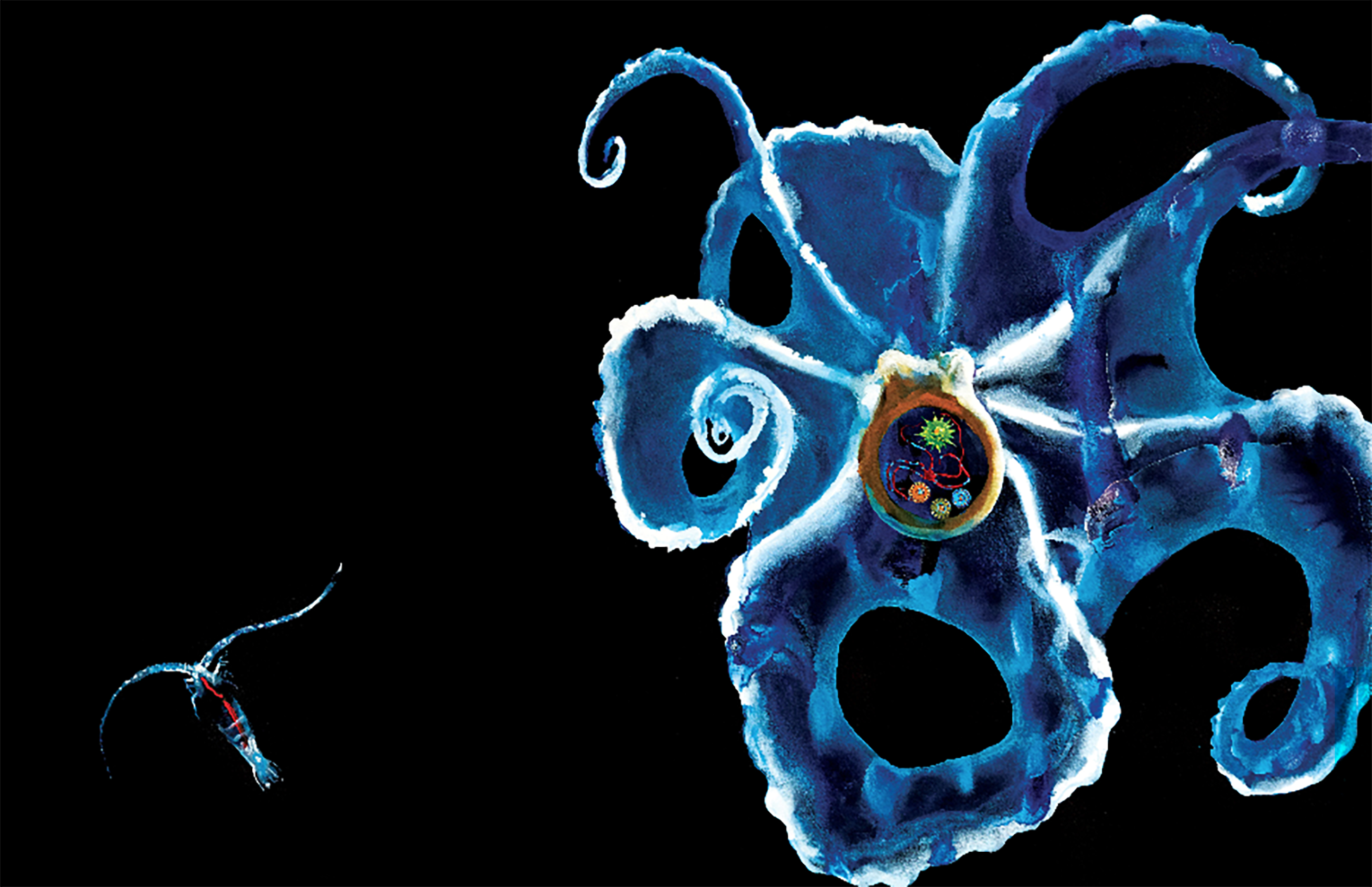

Pages from Alexis Rockman’s “Bioluminescence” project in zingmagazine issue 24, 2013, gouache on black paper, courtesy Baldwin Gallery, Aspen, CO

Technical skill and fantastic imagery make Alexis Rockman’s paintings immediately appealing to the appetites of the eye, but his nimble approach in applying scientific and historical anecdotes satisfies intellectual intrigue. The realms of the real and the surreal meet in a place where jellyfish and tabby cats live amongst sunken bridges and in abandoned buildings. These scenes, though imaginary, are informed by very real circumstances and quantitative evidence which tells us that our earth is changing in alarming yet preventable ways. Integrating with nature by traveling the globe, studying the species and environments he depicts, and sometimes using elements of the ecosystem to create his art are testaments to Rockman’s passions in conservation and environmental activism, but his work carries meaning that extends far beyond those ideals.

Rockman’s “Bioluminescence” project in zingmagazine 24, curated by the Drawing Center’s Brett Littman, depicts a dark, watery world where life generates its own light—a domain so opposite from the terrestrial sphere. These images are a continuation of his artistic contributions to the film Life of Pi, and is a series that he has expressed great joy in creating. A continuation of another series, Field Drawings, is currently on view at the Parrish Art Museum in Water Mill, New York through January 18, 2016.

Interview by Hayley Richardson

Your project in zingmagazine 24 features watercolor paintings of deep-sea bioluminescent creatures, as well as underwater entities of your own imagination. These images share a relationship with a previous project you did when you created concept artwork for director Ang Lee’s 2012 film Life of Pi. Can you summarize how the zing project developed from your experience working on the film?

The images in zing were done in the same language as Life of Pi, with the same materials, and about similar ideas. I had such a great experience working on Life of Pi, but the studio that made it, 20th Century Fox, owned that work. I felt it would be great to revisit that type of work several years later for a show at the Baldwin Gallery in Aspen in 2013.

The work I did for Life of Pi was constructing a narrative visually for a sequence called the Tiger Vision sequence which was when the tiger, Richard Parker, and Pi are in such dire straights both physically and psychologically and spiritually that they come together and voyage to the bottom of the ocean and it’s not clear who’s who. My role was to visualize that and create a cinematic experience. I ended up making about 50 drawings that I showed at the Drawing Center several years after I did the work in 2011. These drawings, in sequence, were used as reference by animators and that became a one minute and twenty-three second sequence. The project for zing was done two years later. There were four years between the time that I first met with Ang Lee in 2009 and when the movie was finished in fall of 2012. There was an earlier version that we worked on in development and preproduction for the movie that no one will ever see because the studio didn’t approve it—they thought it was too expensive. So the Tiger Vision sequence was kind of a condensed and stream lined version of what we wanted to do initially. Ironically, I think it turned out better than what we wanted to do the first time, but getting it to happen was a bit of rollercoaster ride. Ang is a master of the long ball. It turned out fantastic. It was wonderful to see the sequence be so close to the drawings—Buf, the company that did it, did a great job.

The paintings are gauche on black paper, and I read that you had never painted that way before.

I started out making drawings with black ink around the characters to sort of position them in the darkness of the deep sea with no sunlight whatsoever. Then I realized why not just do the damn things on black paper?

There is a style of drawing in India known as kolam, which is characterized by decorative, mandala-like designs, and I noticed that one of your Life of Pi underwater paintings exhibited at The Drawing Center has a white geometric pattern in it that looks very kolam-esque. This design also appears in the movie in the Tiger Vision sequence. I am curious if any visual traditions of India played a role in how you developed this project.

That’s exactly what it is and it was very intentional. That’s what Pi’s mother character does when she’s with Pi and she teaches the pattern and the meaning to him with sand. In our Tiger Vision sequence his mother ends up beheaded by a knife fish.

Did any other visual traditions of India play a role in how you developed this project?

The squid and the whale composites in the Tiger Vision sequence made out of other figures. There’s an Indian tradition of having an elephant made out of many other elephants or what have you. Like Acrimboldo, but Indian.

You grew up in Manhattan and your mother worked at the American Museum of Natural History, where you spent a lot of time during your youth and was great place of inspiration for your artwork. Were you able to spend much time in nature, outside from the museum and the city, as a child?

I went to camp, I went to the zoo. That’s not nature, but it gave me a sense of longing. I also went to Australia. I was very familiar with things out in the world looking at National Geographic or through watching Wild Kingdom on TV.

You have traveled the globe to become closer with the natural environments and wildlife you depict, and you recently spent time in Michigan studying the Great Lakes region for a show at the Grand Rapids Art Museum opening in 2018. Do you travel in preparation for all your major exhibitions, or only certain ones?

I’d say if I can it’s a good idea. I just spent the last couple of days traveling around New York City, throughout the five boroughs.

Was that in relation to your current exhibition, East End Field Drawings, at the Parrish Art Museum in Watermill?

No, it’s for a show I am doing at Salon 94 in April.

Can you talk more about the East End Field Drawings exhibit, like your process in creating the work and how it all came together?

The images are made out of material from the area directly and nothing else but acrylic polymer. They’re minimal, but also very maximal in terms of being pieces from the landscape or ecosystem. They’re made out of sand or soil or leaves. The image is actually made out of those materials. For instance there’s a place called Town Line Beach in East Hampton that had a beached Leatherback Turtle. It had been dead for a couple days and gulls were eating its head. It was an amazing scene. I collected sand from underneath it and made drawings from the sand of that turtle and some other marine life that are common to that particular beach. I’ve done this for the past twenty some-odd years in different places. Tasmania, the Amazon, Madagascar, the La Brea tar pits. They are all Field Drawings, but this is a separate body of work.

What are some places in the world you haven’t been to yet that you would like to visit, whether for research purposes or just for pleasure?

Borneo or New Guinea, or both, amongst many other places. Burundi, Tibet, The Congo, there are so many places I would love to go.

I watched a video of the lecture you gave at The Smithsonian American Art Museum in 2011 and in it you covered a great span of art historical references that have informed your work over the years. Did you begin to cultivate knowledge in this field early in your career?

I’ve always loved art history. Before I decided I wanted to be a painter—I really loved art history and copied many old master drawings when I first started.

Your Wikipedia page says that your work “has sometimes been associated with a new gothic art movement,” which is loosely defined as “a contemporary art movement that emphasizes darkness and horror.” Do you feel your work fits with this description, or is there another current movement or direction you resonate with?

(Laughs) Yes, I saw that and don’t know what that is! I didn’t do that page. I am not against it. I’m like, “alright, whatever you say.” I like Gothic and I like horror, so why not? I’ve always gone my own way so to speak. There are many artists that I admire that might be considered that, but it’s not something we discussed.

You are known as an environmental activist, yet seem hesitant to consider your paintings as “activist artwork.” Can you explain why that is?

First of all it’s art. I think anything anyone does is political, that’s the position I come from. But to label something as activist artwork it really ghettoizes it pretty fast. I’m trying to juggle many things and there’s a rainbow of meaning.

What do you think is the best vehicle to spread the message of environmentalism to a mass audience?

Probably advertising. The skillful way they can sell alcohol to children is probably the best way to get people to care about conservation. If you can sell cigarettes to kids why can’t you get them to care about the environment? I would suggest putting an attractive person in it and there you have it.

Besides the exhibitions we discussed, do you want to talk about any other shows, events, or news that you have upcoming?

I have some things going on but I can’t really talk about it now. “A Natural History of New York City” at Salon 94 in April, 2016. It includes plants and animals from the history of New York City- from dinosaurs from the Cretaceous in Staten Island (145-66 million years ago) to the squirrel in our back yard in the west Village in Manhattan and in between.

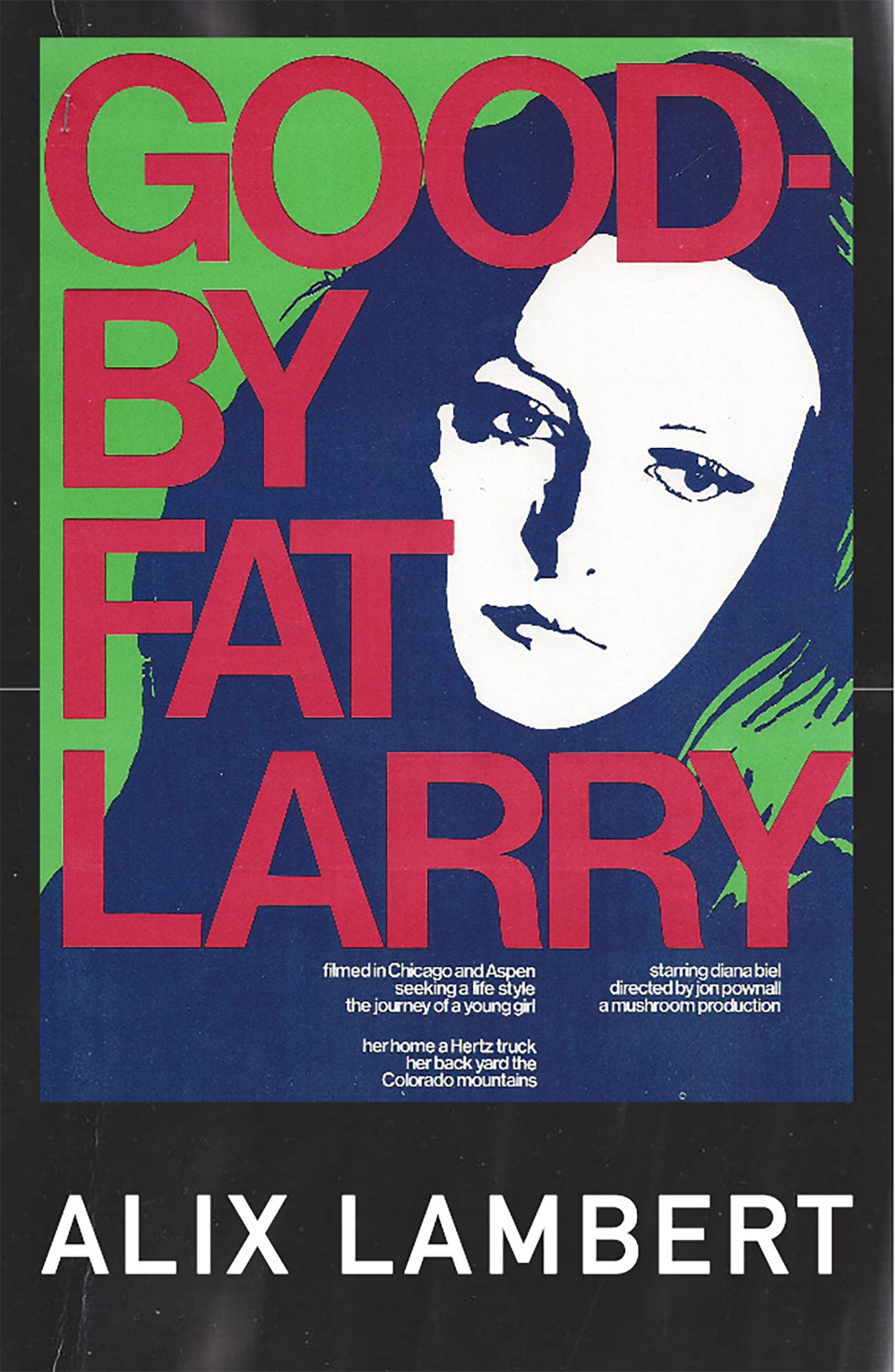

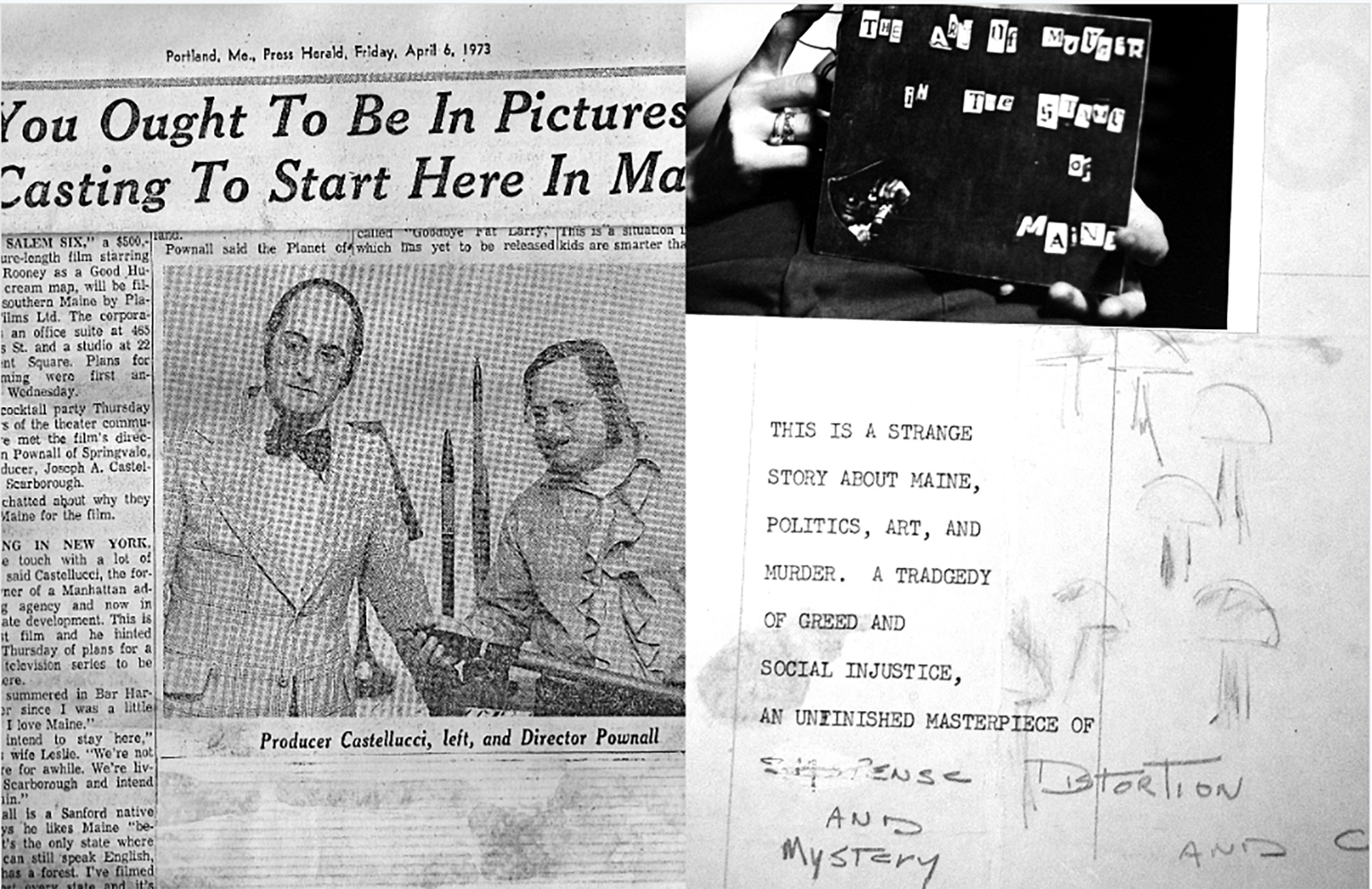

Alix Lambert at London Film Festival

Alix Lambert is an artist, author, documentary filmmaker, and television writer who seeks out and tells the stories of people whose experiences are swept under the rug, often because they contain truths that many choose to ignore. Crime has been a consistent thread in her work for many years and has taken shape in writing, on stage, in prints and photographs, and on film. Some of her notable documentaries include The Mark of Cain (2000) where she integrated herself within the Russian prison system and delved into its forbidden tattoo culture, Bayou Blue (2011) about one of America’s most dangerous yet unknown serial killers from the South, and Mentor (2014), her most recent film focusing on the brutal systemic bullying in an Ohio high school that resulted in an alarming number of teen suicides. While she deals with serious subject-matter, Crime: The Animated Series featured on MoCATV, creatively imbues humor into difficult scenarios and showcases Lambert’s superb ability to collaborate with her subjects and as well as other artists. Her project in zingmagazine issue 24 provides a glimpse at another documentary on which she is currently working about Jon Pownall, who was murdered by one of his associates. The murder is what initially drew Lambert to the subject, but she is more interested in telling the audience about his life and work and how they come together to tell the larger story about that time and generation in American history.

Interview by Hayley Richardson

Page from Alix Lambert’s project in zingmagazine issue 24

Your project in zing 24, “Goodbye, Fat Larry,” displays a collection of images and other ephemera from the archives of deceased director and photographer, Jon Pownall. You are currently working on a documentary about Pownall, and I was wondering if you could talk more about this project and what you’ve learned about him through your research.

I met Lynda, Jon’s daughter five years ago. Working with her over the years and delving ever deeper into this story has been an experience. The story has gotten bigger and bigger, both literally—each individual character has a story line of their own, and metaphorically—the arc really does mirror that of what was happening in America. As a story expands as this one has, I have to also think about the different ways in which it can be told—as a documentary, as a narrative film, as a book, with an app . . . that has been exciting from the perspective of a storyteller.

I read about the app, where users could interact with episodes from the story and respond to it based on the believability of a character or relevance of information. Do you see yourself using technology like this again in the future, and perhaps becoming a trend in film development and marketing strategy?

Yes, absolutely. The app allows me to tell the story in a different way that I find to be valuable and that is different from but related to the other manifestations of the story.

You have said, “crime is a lens through which to look at the world.” This trajectory has taken you on some incredible journeys in achieving your creative goals, from the prisons of Russia to the heart of Middle America. Would you say there was a particular project or moment that solidified your desire to explore within this framework long-term?

I don’t know that I can pinpoint one single moment. I do think my projects kind of overlap each other—hopefully in a good way—I’ll still be thinking about aspects of my last project as I move into something new and those thoughts will manifest in the new work without my even realizing it at first. I don’t think there is much premeditation on my part in terms of what I explore on a long-term basis—I always feel like the work tells me what to do next.

Page from Lambert’s project in zingmagazine issue 24

What do you want audiences to take away from these stories?

It depends on the story—I think my work asks questions more than it has answers—so I am always interested to find out what a person has taken from it.

How do you know when a project/story is finished?

Of course it would be easy to tinker with something forever—but then you’d never get to work on the next thing. I guess intuition? The “story” is never really finished, but with projects I just decide—not a great answer maybe, but an accurate one, I think.

You work in film, photography, printmaking, performance, writing . . . the list goes on. Is there any medium that you don’t have much experience with but would like to explore?

I wish I could sing, or had some kind of musical talent.

I saw that you did put together an album, Running After Deer, in 2008 with musician/producer Travis Dickerson, in which you provided samples from your boxing coach. Would you like to do more musical projects that tie in with your work in other media?

Definitely. I’ve been trying to find the time to collaborate with Travis again, and hope to do that sometime soon.

Collaboration is an important part of your practice. What makes an ideal collaborative dynamic for you?

I love collaborating. I get to work with so many people who I respect, admire and learn from. I enjoy when everyone is bringing different strengths to a project.

Last year you were an artist-in-residence at the McColl Center for Art and Innovation in North Carolina and it seems like you accomplished a lot during your time there. What did you take from that experience?

Speaking of collaborating, I met and worked with the amazingly talented Tim Grant to make a piece I had been wanting to do for a long time. That was exciting.

Page from Lambert’s project in zingmagazine issue 24

Do you see your work as relating to any current movement or direction in visual art or culture?

I am pleased that people seem to be more accepting of interdisciplinary work than they used to be.

How do you navigate between the worlds of fine art and film and television? What advice would you give to other artists who have an interest in interdisciplinary practices?

It has its challenges, but I think people are accepting interdisciplinary artists more than they used to. I hope it continues in that direction.

What artists, filmmakers, writers, etc. have been the most inspiring and influential to you and why?

The list is so so long, I don’t know that I can narrow it down—it so depends on what I am working on and what aspect of the thing I am working on that I am trying to learn about. I watch movies and read and look at art all the time and am humbled.

I am curious about the name of your company, Pink Ghetto Productions.

It was a slang term for women being marginalized in the work force. “Living in the pink ghetto” or “living in the pink collared ghetto.”

What do you like to do in your free time?

I’m pretty boring. I watch a lot of movies and I read books. I take long walks and long baths. I like food.

Besides “Goodbye, Fat Larry,” do you have any other projects or events lined up that you can share?

I am working to complete my book RESCUE. I’m working on it with the support of Jenn Joy and Kelly Kivland who run the new artist collective: Collective Address.

Dike Blair, photo by Aubrey Mayer

As an artist who started his journey in the 1970s by initially dropping out of college, later earning an MFA from the School of the Art Institute of Chicago, and who became an arts professor at the Rhode Island School of Design and an accomplished writer, Dike Blair has had an opportune view of the contemporary creative landscape for several decades. He has exhibited his paintings and sculptures since the 1980s, and a comprehensive showing of his gouache paintings at Karma Gallery this past spring gave not only the public but also himself a panoramic perspective of how much this one area of his practice developed from 1984 until now. In zingmagazine issue 24, Blair brings together the work of four artists and hones in on their harmonious yet distinguished use of color and form in the arc of abstraction. With his range of experience I was interested in his thoughts about the past, present, and future of art and how he blends together his work in writing, painting, sculpture, and education.

Interview by Hayley Richardson

Your project in zingmagazine issue 24, “Ash Ferlito, Steve Keister, Bobbie Oliver, Arlene Shechet,” represents a gathering of four artists whose work you admire and “would look great together.” These are also artists you have worked/exhibited with before, but this is the first time everyone has been involved in a single project together. Any plans to take this from the magazine to the gallery?

I’ve known Steve and Bobbie since the ’70s. Arlene is a prominent artist, but I only got familiar with her work and met her in the last 5 years. Ash was in residence at Skowhegan when I was faculty in 2012. I “curated” this group for Zing (almost 2 years ago) thinking the pages are the show, but it would certainly transpose to an excellent (if I do say so myself) bricks and mortar show.

A page from “Ash Ferlito, Steve Keister, Bobbie Oliver, Arlene Shechet” in zingmagazine issue 24. Top left: Ash Ferlito, “Jacket,” 2013, paper mache, oil paint, wire hanger, 30 x 24 in.; bottom left: Ash Ferlito, “Big Movie Star Mouths,” 2011, oil on canvas, 78 x 66 in; Right: Steve Keister, “Tripod Plate,” 2013, glazed terra cotta, 2 1/4 x 9 3/4 x 9 3/4 in.

Last year you contributed to Ferlito’s Time Capsule 2014 project at the Marjorie Barrick Museum at the University of Las Vegas, in which all contributors agreed to reconvene in 2044 to open the capsule. It’s a long way off from now, but is there anything you see happening now in the creative world that could have a lasting effect on the future of art’s place in society? What do you anticipate it to be like to open that capsule?

I rather doubt I’ll be alive for the opening of the capsule, but Ash probably will, and I imagine it will be an emotionally rich experience.

As to what’s happening now, culturally, that might shape the world, it would certainly have more to do with technology than things like painting and sculpture. One of the nice things about those latter activities is that they are part of a continuum that evolves, and like evolution, there are periods of accelerated change. I don’t think we’re currently in one of those periods.

Art and technology seems a somewhat different story. In general, since more people have tools and venues to express themselves, it does seem that the web of cultural expression has gotten richer and more complex—more and more domains are created. I’m not certain about the quantity to quality issue . . . bad art can be made in any medium. And it worries me a bit that because of technology we can no longer forget. If one personifies culture, the inability to forget may not be a healthy thing.

That’s interesting you bring up evolution because critic Christian Viveros-Faune made a comment earlier this year saying that the art world is now in the Jurassic period, where teeth and claws are necessary for survival in the financial jungle. He suggests that development in contemporary painting has stalled, though, because artists and the venues that show their work are trying too hard to mimic what was successful in the past to please collectors. Do you think this is partly why painting and sculpture are in a “slow” period? What might be some other potential reasons?

Despite having just done so, I’m hesitant about negative judgments about the state of the art world. It’s so age appropriate for the old guy to grumble about how things were once better. Certainly more artists, particularly young ones, have the opportunity to sustain a practice. I remember other bull market periods when the art world attracted clever, lesser talents who enjoyed success and why not? There will most likely be some kind of correction, but I’m not necessarily wishing for that.

Dike Blair, “Untitled,” 2015, gouache and pencil on paper, 20” x 15”

Earlier this year Karma exhibited Gouaches 1984–2015, and, from what I understand, the paintings were exhibited chronologically. What was it like seeing 31 years worth of just your painted work at once?

Yes, chronologically, and I have say, the whole experience was edifying. We organized the show and book in a very few weeks, so almost all of the work was from my studio, including stuff from the mid-80s that had sat on a shelf, untouched for 30 years. Those were covered in dust and because I made the very primitive frames with hot glue, they literally fell apart when I picked them up. Showing those first gouaches was a little difficult for me. I didn’t really know how to paint when I did them; but Brendan Dugan of Karma and Dan Colen, who brought Brendan over to my studio, were so enthusiastic about them I decided to include them. I was a little surprised that people responded so well to them.

Your apprehension showing the early paintings . . . does this relate to your worry about the inability to forget?

Not directly. I think most artists like to think the work they’re currently engaged in is their best. Of course that’s not always true, so one needs to delude oneself.

Your paintings are mostly untitled, except for a few that note a person’s name or a location in parentheses, whereas your sculptures have enigmatic titles like “a seagull suddenly submerges.” How do you name an artwork?

I think the representational don’t need titles. It’s a cocktail, or a sunset, or something. The sculpture is more enigmatic and something suggestive can encourage poetic readings.

How do you balance your time between making paintings and making sculptures? Do you work in the two media simultaneously or focus more on one and then switch after a while?

I have two studios. A small one in the City that is only appropriate for the small paintings on paper, and a larger one upstate where I can work on sculpture and other large projects. So I tend to work on sculpture in the summer, and paintings during the school year.

Dike Blair, “129,” 2014; painted wooden crates, framed mixed media. H 72” W 105” D 99”

What are some of your favorite galleries/museums/art venues? Any recent exhibitions that really caught your eye?

The Noguchi Museum in Queens is probably my favorite museum. He’s one of my favorite 20th century artists, and the space is serene. I saw an exhibition in LA of Archibald Motley’s paintings that blew my mind. Somehow I was ignorant of his work and it’s amazing. That same show, I think, will travel to the Whitney this fall.

You attended a number of different art schools in the 1970s and are currently a painting professor and Senior Critic at the Rhode Island School of Design. How would you compare what art school is like now to when you were a student?

Schools and the art world were obviously very different back then. Of course the scale of everything was smaller, and theory wasn’t so predominant. Professors were generally less demanding, and some (and I emphasize, only some) of them considered teaching as something like a professional grant rather than a job. I demand so much more of my students, namely attendance, than was demanded of me. I’d also note that I would hate to have had me as a student. I would have to slap me down.

I attended a talk earlier this year with a group of artists who founded some of the first DIY art spaces in Denver in the ‘70s, and they discussed how today’s young artists are trying to make art as a career rather than creating out of passion. Any thoughts on this statement and it how might relate to the shift in how schools/the art world operates?

Well, I wanted an art career when I was in school in the early ’70s, also in Colorado. I think one’s approach to making art constantly changes over a lifetime. In my case my sense of accomplishment, or lack of it, was probably more of an external thing when I was young, and now it’s more internal.

You’ve conducted and been the subject of many interviews. What do you think necessitates a good interview, from both the interviewer and the interviewee?

One of the things I most liked about interviewing people was the preparatory homework. Of course 95% of that homework doesn’t get touched in the interview, but it’s great to get outside of oneself and really think about the subject. I think in my early interviews I wanted to demonstrate to the interviewee, almost always a person I admired, that I was smart. Well, I’m not that smart and I realized the interviews were often better when I didn’t try to be.

When interviewed, I try to be somewhat honest.

How do your practices in art and writing inform one another?

Well, when an artist writes, inevitably there’s a two-way bleed. However, in the mid-’90s I made a very conscious effort to segregate the studio work from the writing. I didn’t want the art to explain itself and I eschewed starting a work with a concept. I think the art I made might be difficult to write about. I’m certainly not prescribing that approach and it seems a great deal of successful contemporary stuff starts with a concept that’s relatively easy to translate into words.

Christopher K. Ho was asked which art critics have been influential to him, and which artists who write or engage in some form of criticism he respects. He named you, among others, in his response, and I’d like to redirect that question back to you.

Thanks for that link. Chris is a friend and colleague and I’m embarrassed I didn’t even know about Hirsch E.P. Rothko. Chris is brilliant but not one to hoist his own petard. I just ordered it.

I really don’t read much art criticism and mostly read fiction. Actually, I don’t even read much anymore and mostly listen to audio books. I would like to echo Chris in my admiration for Roger White, I loved his book, The Contemporaries, and with Dushko Petrovich, he creates Paper Monument, one of the only art magazines I read. Like Chris, I admire Rosalind Krauss, however I prefer journalistic art writing to more critical stuff. Dave Hickey’s books always grab me, and I just finished Greil Marcus’s, The History of Rock ‘n’ Roll in Ten Songs…really great. (Actually, listened to that, and Henry Rollins’s read it really well.)

A page from “Ash Ferlito, Steve Keister, Bobbie Oliver, Arlene Shechet” in zingmagazine issue 24. Left: Arlene Shechet, “Night Out,” 2011, glazed ceramic, painted hardwood, 45 x 13 x 17 in. Right: Bobbie Oliver, “Laguna 2,” 2013, acrylic on canvas, 36 x 40 in.

What else are you listening to, looking at, or reading to fuel (or perhaps escape from) your work?

The NFL season has just started. That’s an escape. I just heard the music on Jeff Rian’s CD that’s included in this issue of Zing. He’s an old friend and the music is really beautiful.

Do you have projects, exhibitions, or anything else coming up on the horizon you’d like to share?

I’m really excited to be doing a show at the Vienna Secession early in 2016. It will be paintings and sculpture about windows, walls, floors and doors.