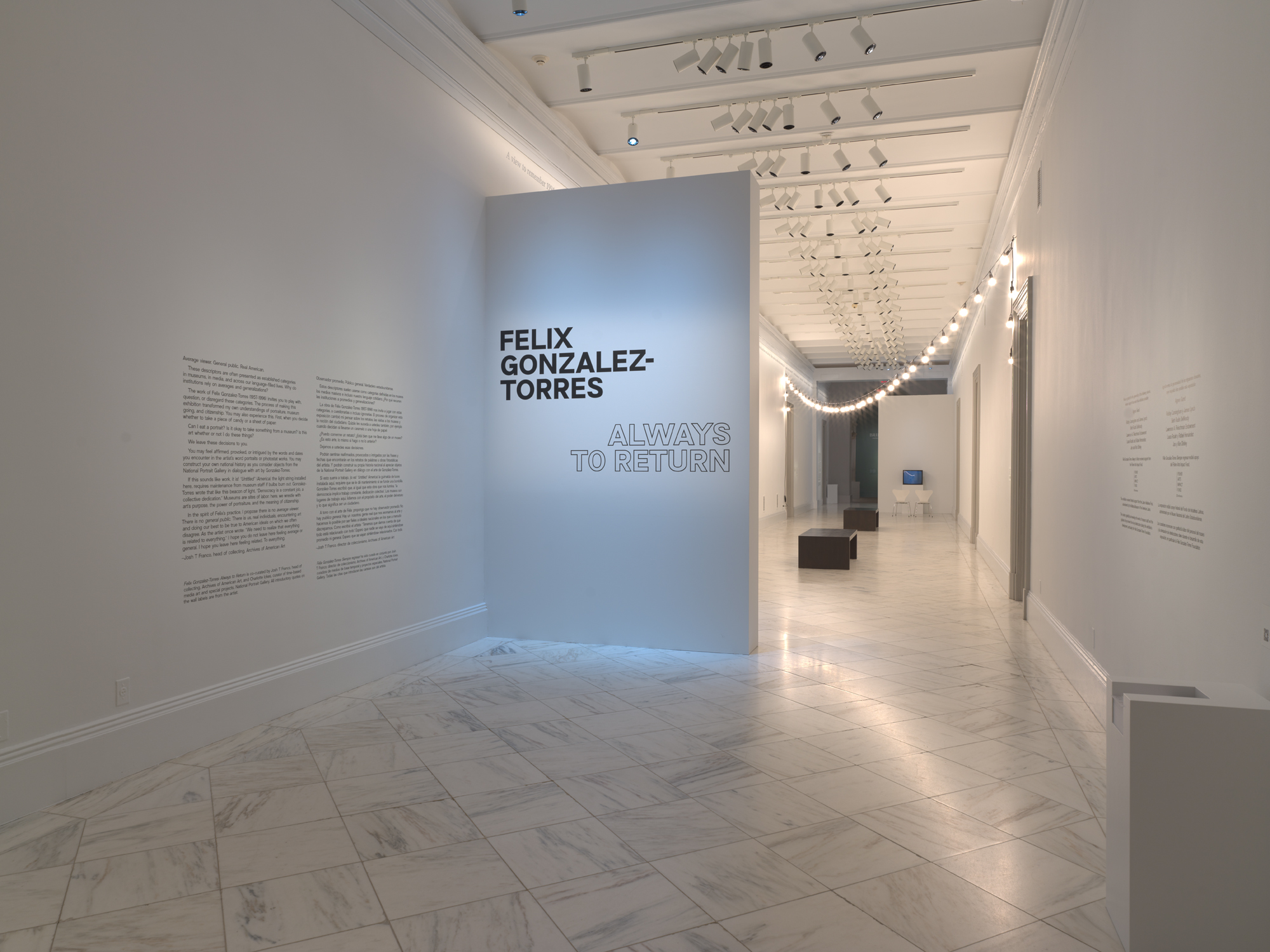

Installation view of “Felix Gonzalez-Torres: Always to Return”

Photo by Mark Gulezian/National Portrait Gallery

Art historian Charlotte Ickes is Curator of Time-Based Media Art and Special Projects at the National Portrait Gallery in Washington, D.C. Among her recent projects, she co-curated Isaac Julien: Lessons of the Hour—Frederick Douglass (2023–2026) and Viewfinder: Women’s Film and Video from the Smithsonian (2021). She also commissioned Birthright (2022), a performance by Maren Hassinger. Her latest exhibition, Felix Gonzalez-Torres: Always to Return, is co-curated with Josh T Franco, Collector at Large at the Archives of American Art.

Charlotte Ickes as Interviewed by Claire Dillon

I love it when people say: ‘But it is just paper. It is just two clocks next to each other. It is just light bulbs hanging.’ I love the idea of being an infiltrator. I always said that I wanted to be a spy. I want my artwork to look like something else, non-artistic yet beautifully simple.

– Felix Gonzalez-Torres in conversation with Tim Rollins, 1993

The exhibition Felix Gonzalez-Torres: Always to Return begins outdoors, beyond the walls of the National Portrait Gallery and Archives of American Art. Visitors first encounter strings of lights from “Untitled” (America) (1994) hanging from the venue’s façade, lining 8th Street NW, and shining through the windows of the Martin Luther King Jr. Memorial Library next door. When I saw the exhibition in December 2024, “Untitled” (America) was also intertwined with a second set of lights, which decorated the local holiday market. As they subtly swayed in the crisp air, the warm glow of the artwork’s frosted bulbs contrasted with the clear lights installed for the season’s festivities.

A label accompanying this installation can be found indoors and through QR codes pasted to the sidewalk. The text in the library explains the key components of the work, and continues with an interpretation:

When illuminated, “Untitled” (America) requires continued maintenance from library staff who must replace burned bulbs. ‘Democracy is a constant job, a collective dedication,’ Gonzalez-Torres wrote in a statement about “Untitled” (America). As a beacon hovering between promise and precarity, this work, like democracy, requires choice, maintenance, vigilance, and labor. During election season, the DCPL [District of Columbia Public Library] serves as a voting site. Without voting representatives in Congress, D.C. residents are only partially enfranchised. Exhibited in this context, what meanings about democracy does this work generate? As the artist said he hoped the work ‘will light some peoples’ spaces, at least for a short time.’ Hopefully, “Untitled” (America) ‘lights your space’ as you read, eat, and attend civic programs at the library, the museum across the street, and elsewhere.

This brief description of the installation raises several themes that permeate the work and this exhibition: by using everyday objects to create untitled artworks, most of Gonzalez-Torres’s pieces remain open to infinite interpretation. While his parenthetical titles suggest directions for contemplation, the responses of the audience and curators are just as important as the artist’s intentions. In this case, the title of the work and its installation by a museum of portraiture prompt consideration of the conventions of representation, not only of people, but also of concepts like America.

Site-specific interpretation is a recurrent theme in this exhibition of Gonzalez-Torres’s art, and it is particularly significant because this is the first major presentation of his work in the nation’s capital in three decades. Collaborating between the National Portrait Gallery and Archives of American Art, Ickes and Franco staged original juxtapositions between the institutions’ permanent collections and Gonzalez-Torres’s work. In doing so, they interrogate the themes of portraiture, institutions, politics, and constructions of public, private, identity, and history. For example, the artist’s photographs of the American Museum of Natural History’s memorial to Theodore Roosevelt—documenting only the engraved words Historian, Scientist, Statesman, and Ranchman rather than the infamous equestrian statue—are displayed next to Roosevelt’s painted portrait in the Gallery’s permanent exhibition, America’s Presidents. Gonzalez-Torres’s nonrepresentational approach challenges expectations of what a portrait can be, and this exhibition created unique opportunities to compare his work with traditional definitions of this genre.

The extension of Gonzalez-Torres’s work into other exhibitions within the museum and into the city recalls an oft-quoted 1995 interview with Robert Storr, in which the artist stated:

There’s a great quote by the director of the Christian Coalition, who said that he wanted to be a spy. ‘I want to be invisible,’ he said, ‘I do guerilla warfare, I paint my face and travel at night. You don’t know until election night.’ This is good! This is brilliant! Here the Left we should stop wearing the fucked-up T-shirts that say ‘Vegetarian Now.’ No, go to a meeting and infiltrate and then once you are inside, try to have an effect. I want to be a spy, too. I do want to be the one who resembles something else. We should have been thinking about that long ago. We have to restructure our strategies and realize that the red banner with the red raised fist didn’t work in the sixties and it’s not going to work now. I don’t want to be the enemy anymore. The enemy is too easy to dismiss and to attack. The thing that I want to do sometimes with some of these pieces about homosexual desire is to be more inclusive. Every time they see a clock or a stack of paper or a curtain, I want them to think twice.

Today, his piles of candy and stacks of paper stand quietly, but powerfully, among works in the permanent collection. In my mind, the presence of Gonzalez-Torres’s work amidst both a holiday market and an exhibition of presidential portraits is a perfect demonstration of this strategy. In another example, pictured below, the artist’s paper stack “Untitled” (Death by Gun) (1990)—a record of 464 victims of gun violence in the first week of May 1989—sits beneath Christian Schussele’s painting Men of Progress (1862), which depicts American inventors, including firearms manufacturer Samuel Colt. The men are represented in a fictive meeting in the very building in which this exhibition is now held: the former U.S. Patent Office. This pairing attests to the artist’s ability to intervene in such institutions, and the curators’ careful consideration of the site in which they work.

Felix Gonzalez-Torres, “‘Untitled’ (Death by Gun)”

© Estate Felix Gonzalez-Torres

Courtesy Felix Gonzalez-Torres Foundation, Photo by Mark Gulezian/National Portrait Gallery

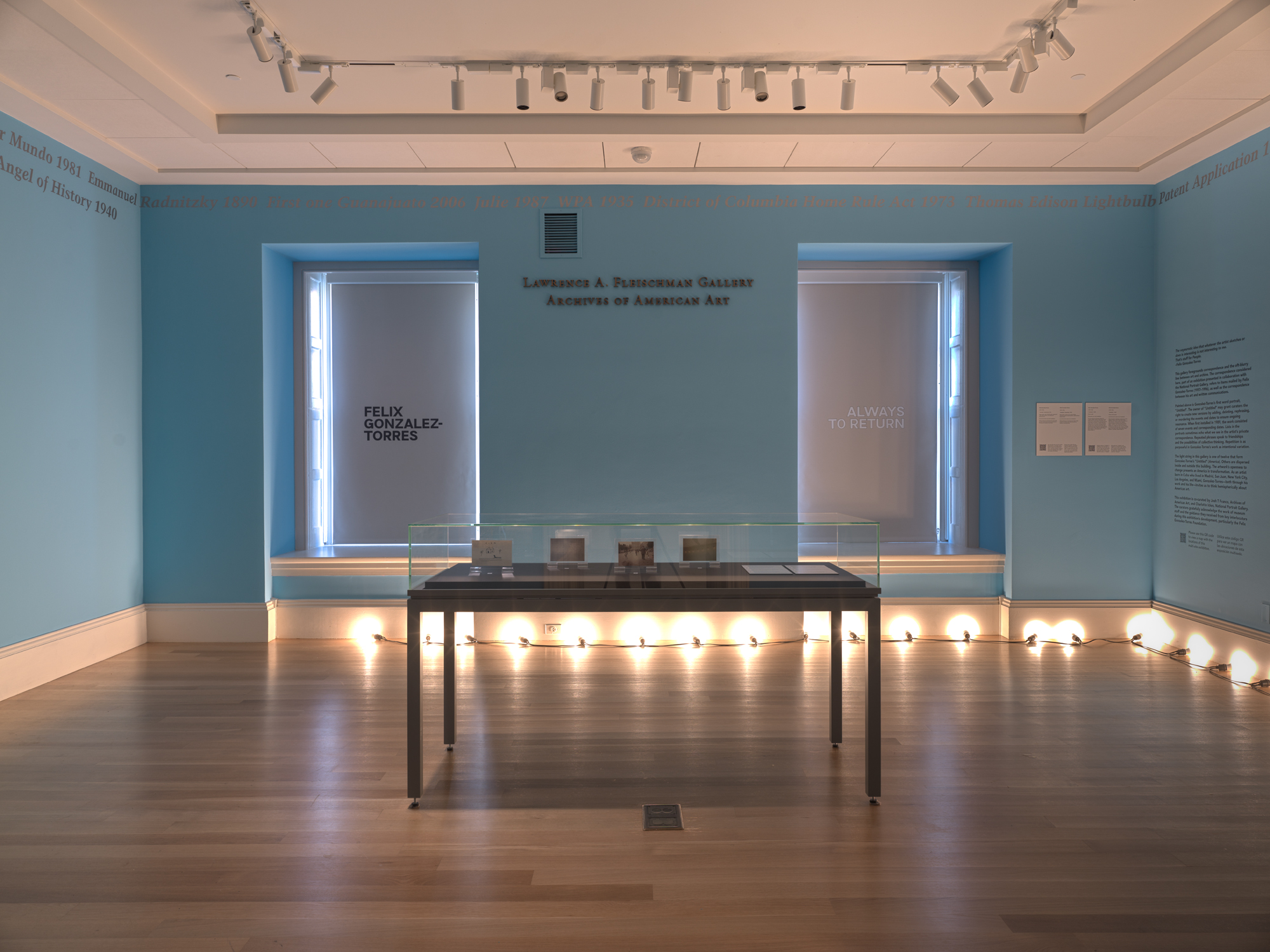

Gonzalez-Torres’s art also reaches into the present, which is most evident in his exhibited word portraits. These portraits, composed of formative events listed in silver paint around the perimeter of a room, were made with the input of their initial owners to create a timeline of personal and public moments that represented them. New versions of a portrait can be created with the owner’s permission, and in this exhibition, events such as “CDC 1981” are joined with “PrEP 2012” and “CDC 2020,” which occurred after the artist’s untimely death from AIDS-related complications on January 9, 1996. Other posthumous events include “January 6 2021” and “Equestrian Statue of Theodore Roosevelt 2022.” In this way, Gonzalez-Torres’s work, and particularly his conceptual portraits, represent not only specific people, times, or places, but also the broader contexts that surround their beholders and the institutions in which they are exhibited.

Felix Gonzalez-Torres, ” ‘Untitled’ (Portrait of Dad)”

© Estate Felix Gonzalez-Torres

Courtesy Felix Gonzalez-Torres Foundation, Photo by Mark Gulezian/National Portrait Gallery

When I visited Felix Gonzalez-Torres: Always to Return, I was struck by the juxtaposition between the interpretive openness of Gonzalez-Torres’s work and the specificity of the National Portrait Gallery’s mission to “tell the story of America” through portrayals of the nation’s people. How did you formulate the ideas behind the exhibition?

I saw Felix’s word portraits at Andrea Rosen Gallery in 2016, in an exhibition curated by Julie Ault and Roni Horn. They blew me away with their complexity, as they told history differently through portraiture, and I wondered how that process could be modeled in an exhibition.

Felix’s work is exhibited all around the world, so I knew that place and context would be critical in order to bring something additional to the work. We got very specific about site: our site as a collection, our site at the Smithsonian, and our site in Washington, D.C. This involved placing art from the collection in conversation with Felix’s work, and then moving the exhibition out into our city.

When I started at the Portrait Gallery and learned that the Archives of American Art was home to the Andrea Rosen Gallery records, I approached Josh Franco about a potential collaboration between us and our two units, as we call them in the Smithsonian. I like collaborating, and more than that, I was trying to create a discursive conversational format that would make the sum greater than its parts.

Collaboration pervaded my experience curating the show and writing new versions of his word portraits. This approach complemented the doubling, twoness, and coupling that are present throughout Felix’s work. With the Archives’ footprint in the museum building, we had the opportunity to move beyond one single space, which highlighted the multifaceted nature of his portrait practice. Between his artwork and his correspondence, we see the logic of lists, the major and the minor, and other themes echoed across different materials. The Archives offered a great space to do that work.

I was originally thinking about a survey of his portrait works, but we moved away from that format through conversation and deeper thinking. That’s something I’ve learned from Felix: his work is about being open and humble enough to know that you might start with one idea, but you also have to learn and let your thinking change. This is now how I want to approach everything I do.

There are moments when the exhibition refers to the history of the institution, and I noticed that, in some ways, the galleries form a portrait of the National Portrait Gallery itself. Did you and Josh see your work in this light? In what other ways did the venue inform the exhibition?

As a curator, I think one of my responsibilities is to create a conversation between the context in which the work was made and the context in which it is exhibited now. Greg Allen articulated this so beautifully in a recent blog post about the show. It just so happens that, within this exhibition, some of that conversation includes the history of the building and the institution.

I hadn’t originally thought of the exhibition as a portrait of the institution until I was asked. I think that it could be. Felix made word portraits of institutions, which prompt a key question: who gets to represent the institution? A really beautiful takeaway from the institutional portraits—like “Untitled” (Portrait of MOCA), which we have on view—is that an institution is ultimately made of people. It’s a portrait of MOCA, but there always has to be a person to make the versions of the word portrait, or interact with lenders, and so on. That tension is really interesting to me. An institution is a mission statement, it’s a building, it’s a set of systems, but it’s also made of people, and it’s not static. That informed our decision to write and sign two different introductory statements to the exhibition. We wanted to destabilize the idea of an authoritative institutional voice. While the exhibition relates to the institution, it’s also a model of how we tell history, which I see Felix working through in these portraits.

I did fear that that displaying figural works from the Portrait Gallery collection alongside Felix’s pieces, speaking directly to some of his parenthetical titles, could close down the potential meanings of his work. I hope that this approach presented the art in unexpected and meaningful ways. In doing so, I could see his work with fresh eyes. Through that process of thinking about these connections, I strove to model the kind of history-writing that he proposes with his art.

What was the process of contributing to the word portraits? Did you think of these interventions as expanding a portrait of the subject, or of creating a portrait of you and Josh, or as something else?

When you borrow a word portrait, you don’t automatically have permission to create new versions, but we were granted that right with all three of the word portraits in the exhibition. The process for each portrait was different, and frankly, I didn’t know what to expect going into it.

Robert Vifian, the subject of one of the exhibited portraits, is amazing. I’m so thankful that Felix’s work allowed me to be introduced to him. Robert collected other works by Felix and commissioned this word portrait; he is a really visionary collector. He happens to be both the owner and the subject of this piece, and it was great to co-write this version with him.

This is the first time that his portrait has been shown in the U.S., and we took a pretty light touch with it. He told us which version he wanted to use, and most of what we added spoke to the context of the room in the exhibition. Then, as a result of our conversations, Robert added a few new events and dates. Josh had the opportunity to go out to Paris and saw a version of the word portrait installed in Robert’s home, ate at his restaurant, and went to visit the Gertrude Stein & Alice B. Toklas grave, which was the subject of two of Felix’s other works in the exhibition. It was Josh’s first time in Paris, and it was all kind of framed by Felix.

Bringing “Untitled” (Portrait of MOCA) to the East Coast, to a very different kind of institution, came with a very different kind of site specificity. When displayed in the Smithsonian, “MOCA” is not necessarily recognizable, as it’s not even spelled out in the title. It required a real balance between being a portrait of MOCA or the Portrait Gallery, and our thoughts of MOCA and L.A.

I would say that “Untitled” was the hardest one. I still think about it—and have my regrets! This was Felix’s first word portrait. When it was first shown at the Brooklyn Museum for VisualAIDS’s inaugural Day Without Art in 1989, it only consisted of seven events and dates. But now there are more than forty versions. It also grew during his lifetime. We wrote two versions of “Untitled” for the exhibition. One version is installed in the main corridor of the exhibition, and a different, shorter version is in the Archives of American Art gallery in the same building.

We couldn’t help but think about the fact that, at one point in time, Felix called it “Untitled” (Self-Portrait) for his show at the Hirshhorn in 1994. He ultimately landed on “Untitled.” It’s the only word portrait without a subject named in parentheses. That makes it hard: it’s totally expansive. At the same time, I couldn’t get out of my own head knowing that a lot of the work’s reception centered on the former title, “Untitled” (Self-Portrait). However, these interpretations are not mutually exclusive: biography is there, and so are other things. They inform each other.

The word portraits are supposed to include events and dates that were formative for the subject. But this one doesn’t name a subject: could the subject be us, our personal lives, our professional lives? Does that distinction even matter? It’s a really difficult process and a huge responsibility. There is a generosity to it, sure, but Felix makes you work hard, and in ways that you aren’t trained to work.

To begin drafting new versions of “Untitled” for the exhibition, we reserved the Archives of American Art conference room and covered long tables with butcher paper. We read aloud all of the past versions of the word portrait, wrote them down, and started moving things around and talking it out. You begin to notice patterns and repetitions across portraits. It’s an overwhelming amount of information. I asked an intern to research almost every single term. Of course, sometimes we just didn’t know what a term meant, and each one could have multiple possible meanings. We tinkered on our computers for months at a time, had another retreat, printed out the text to scale and arranged it around the rooms, and we only stopped when we had to get a quote from the sign painter. We also had to make decisions during the installation. For example, all three portraits call for metallic silver paint, but we had to decide what that meant. The Archives space is painted blue, so it was harder to read the paint color that we used upstairs on white walls. With our permission, Sean Danaher, the sign painter, added a little pewter to make it more legible.

Installation view of “Felix Gonzalez-Torres: Always to Return”

Photo by Mark Gulezian/National Portrait Gallery

I imagine all of these materials from the retreats are kept somewhere?

I think it’s all in Josh’s office. The paper has food stains on it from lunch and snacks; we were in that conference room all day. That’s the thing about this work—you can’t just put something on view and write a wall label.

The work really brings people together; I love picturing Josh in Paris with Robert.

The world Felix built was so amazing. Some of the people we’ve met… I treasure those conversations. In terms of this exhibition, I’m very cognizant that we curators come from a generation that is several generations removed from Felix’s life. Many of the great shows were done while he was alive, with people who knew him, or who had lived experience of his generation. I’m very aware of our distance, and I’m not saying that one is better than the other. It just is.

Did the nature of the art or of the exhibition create opportunities to work in new ways, either for you as a curator or for your colleagues? I’m struck by the amount of physical work involved: clearing debris from the candy piles, straightening up the paper stacks, and so on.

The caretaking is significant. Josh and I have done a lot of hands-on work, including during the installation. The maintenance of the show is a huge amount of effort—it’s way more than I expected and has been a real learning experience. We’ve done at least five roll calls with our security colleagues and are in continuous conversation. The work also entails care and tending in physical ways: replenishing piles and stacks, tidying things up. I’m always removing the scuff marks from “Untitled” (Death by Gun).

It’s so complex. This is only the tip of the iceberg, but I know that my experience with Felix’s work and keeping it on view will forever change the way that I approach my curatorial work. His art will always be with me in that way, long after the show closes.

Could you return to the title of the exhibition, and take us through how you chose it?

The title is from the video “Untitled” (A Portrait), which for me, is one of the most significant works in the exhibition. At one point, we thought of using “Angel of History” as the subtitle, from Walter Benjamin’s Theses on the Philosophy of History, which is important to our thinking, and Felix was a great reader of Benjamin. We have “Angel of History 1940” in the version of “Untitled” exhibited in the Archives space. We ended up choosing the title “Always to Return,” and the piece that it comes from still feels so resonant now, decades after it was made. It’s both of its time and of our time. The work says things like, “a new Supreme Court ruling,” or “a distant war.” It also includes “a shortness of breath,” and we worked on this during Covid. These histories are a series of returns.

I was also thinking about “returns” while you described maintaining the work. The art may be generous, but it also demands a lot of its caretakers; it requires that you physically return to the work in order to care for it.

Yeah, that’s funny—it’s also a physical return. In the most basic way, it underscores the root of our profession, cura, curating as a form of care.

Another way to think about returns involves the ways in which many of us keep returning to Felix’s work. I think it’s because of that beautiful tension in the art, which prompts us to think through the moment in which it was made and the world in which it is exhibited now. It underscores this idea that the past always returns to shape our present.

It’s interesting that people still refer to him by his first name, even those that didn’t know him personally.

Yes, it’s a phenomenon that Glenn Ligon and Joshua Chambers-Letson have written about. There’s also “FGT.” I can’t think of another artist like that. There’s something in the work.

We half-joke that Felix is the third curator, because his work is not only the subject of the show—it’s also the structure of the show.

Claire Dillon

Rome, Italy

April 2025

Claire would also like to thank Josh T Franco for meeting her in the galleries and for his contributions to this conversation.

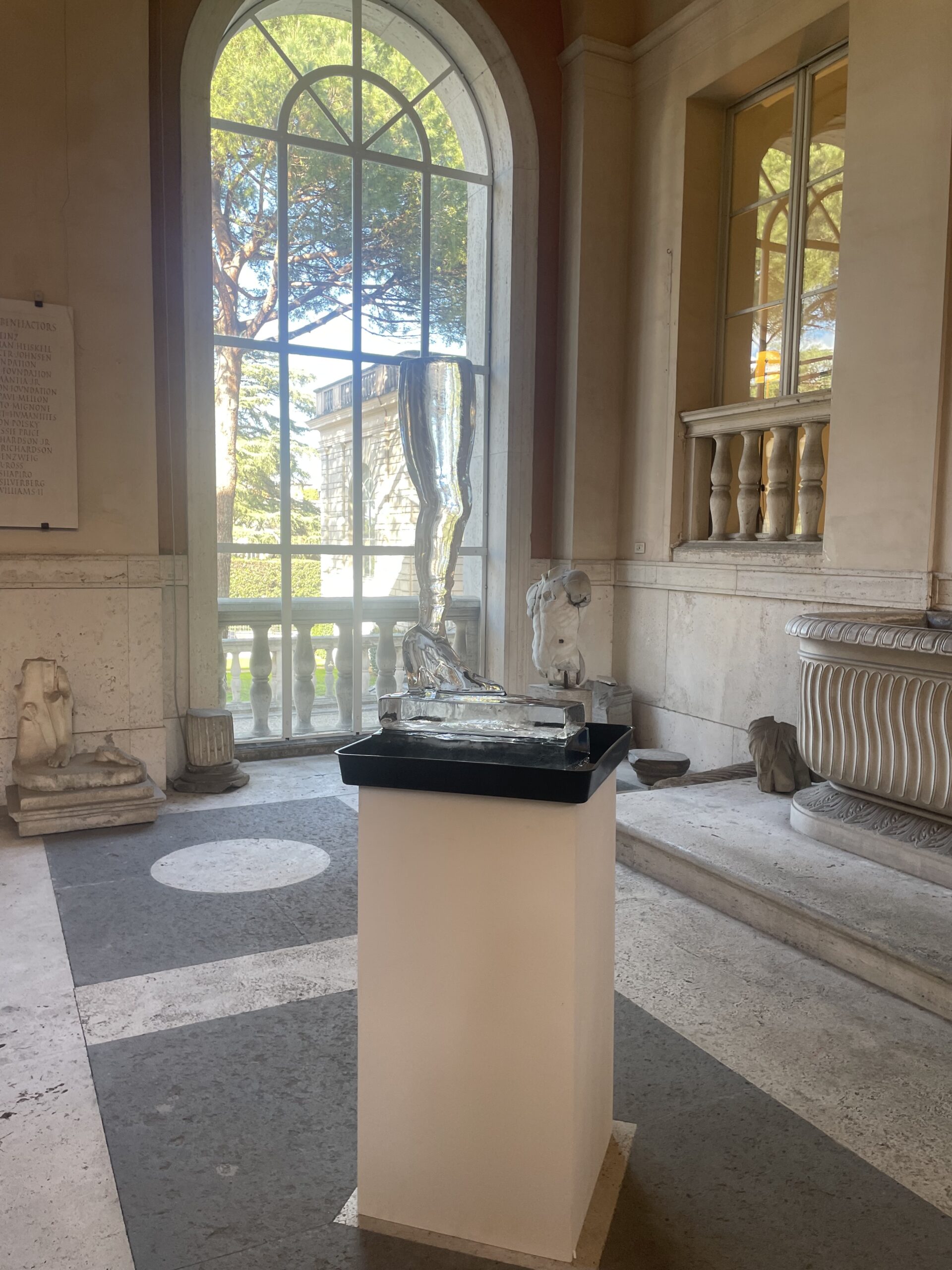

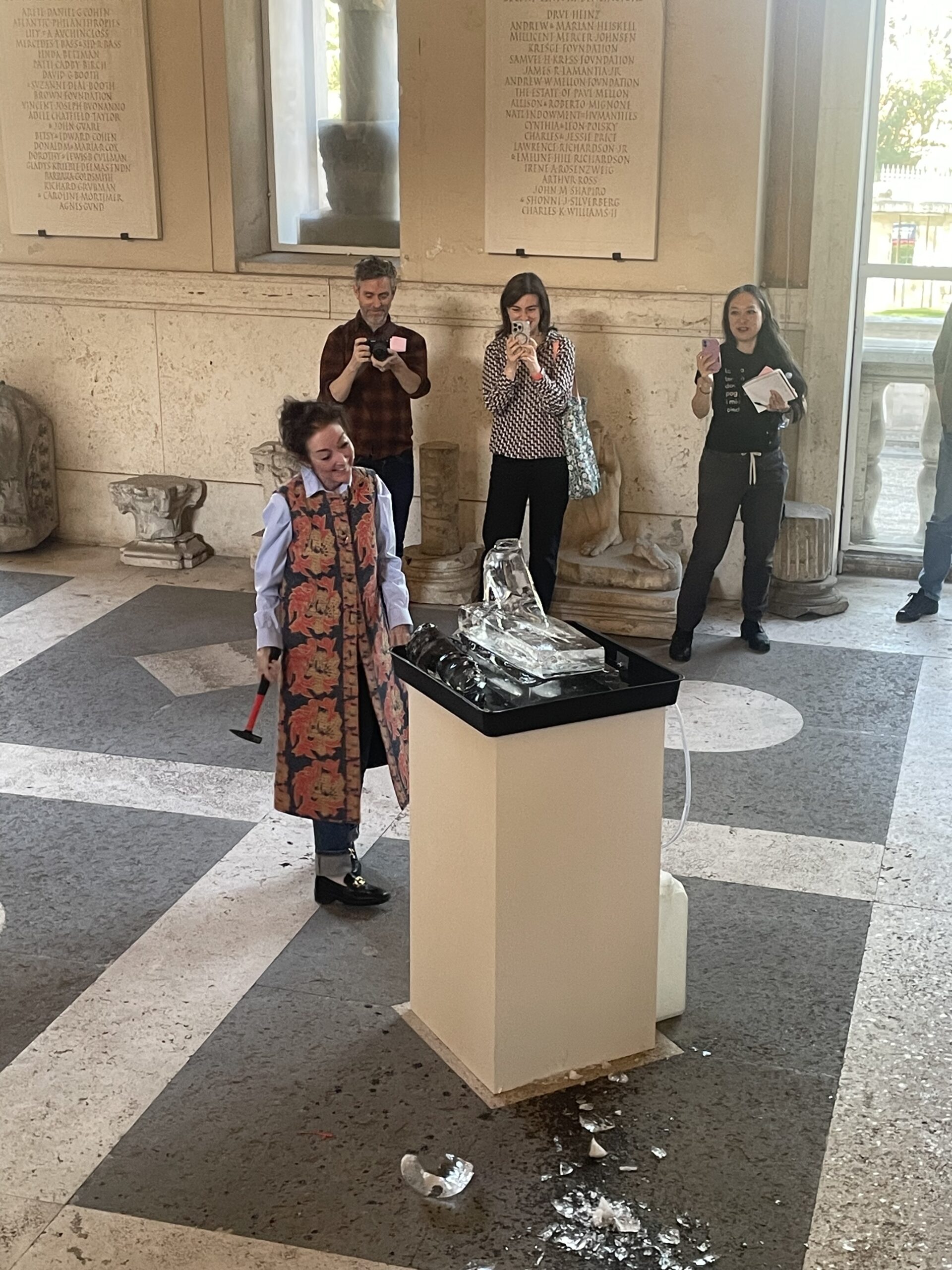

Lizzi Bougatsos, Self Portrait, at the American Academy in Rome

On March 31st, Devon Dikeou brought Lizzi Bougatsos’ Self Portrait to the American Academy in Rome, as part of a presentation with art historian Julia Rose Katz, after they realized that they both shared a connection to Bougatsos – Dikeou as the largest collector or her artwork, and Katz whose work is influenced by her personal experiences that evoke themes of breakage and repair as well as the use of found objects, also characteristic of Bougatsos’ work. Self Portrait, a mold of the artist’s leg in ice, posed a playful (and temporary) addition to the collection of fragments from Roman statues in the lobby of the Academy.

In an art market where money is the medium, Bougatsos’ sensibilities remain refreshingly punk. In an interview with zing she once explained that she considered art to be, “basically a gluttonous production of waste and more garbage and more things that we’re going to have to bury,” when asked why she’d turned to working with ephemera like garbage, living plants, and of course–ice.

Because of her concerns with medium, Bougatsos’ work often feels like it’s mid-process, like a force of nature, something that is always becoming something else. She refers to this ecstatic dance of creation and destruction, writing in a contributor’s statement for zing #24, as if a priestess invoking primal forces:

Aloe dripping from their tongues as they chant the sounds of God, ancestors, jungle flora, and spit. Money is flying. No one gives a shit but they want it all and the rum on the top of the pole, greased with lard.

The project for which this statement was written, Looking for M.J., presents a kind of visual poem that operates on an instinctive logic rather than an intellectual one. Right away, reality is suspicious. The title, which alludes to the conspiracy theory that Michael Jackson faked his death (as Elvis and JFK before him), is paired with an image of a man in a Bigfoot-like mask. Later, a blurry image of a woman awkwardly wrapped in a blanket channels Warhol’s Suicide (Fallen Body). There’s a sense of the mythical, but also a sense of the absurd.

two-page spread from Looking for M.J., zing #24

Across 14 pages, images continuously talk to each other in a way that is only partially comprehensible: a photo of a dance party across a table of toppled wine glasses; a few pages on, a single wine glass casts its ghostly outline onto a wall—across from a gnarled, split tree root, which resurfaces in the background of an image of a Virgin and Savior headstone in a cemetery, thematically echoing the ghostly outline of the glass.

Devon Dikeou showing how it’s done at the American Academy in Rome

There’s something about the vibrant and gritty energy of Bougatsos’ work that feels like you’re at a house party at the end of the world – ancient statues reduced mostly to kind-of-cool rocks, mourning dressed up as nightlife. Ice melts and mountains crumble. All civilizations end up as ruins. It’s strangely comforting in 2025 in a world that feels like it’s perpetually collapsing to go on anyway, dancing on the edge, waiting for the bass drop.

-Rachel Dalamangas

Correction: An earlier version of this post mistakenly referred to Katz as Rose Katz. Additionally, language was adjusted to better describe her relationship to Bougatsos’ work.

Lessons of New York is an unfinished collection of oral histories from the LES art scene of the 70s and 80s

Walter at zing #22 release party in Miami, December 2011

I first met Walter in 2013 when I interviewed him at his LIC studio for zing, shortly after moving from Denver to NYC. I was a walking cliché of a cliché – a young writer in New York.

After the interview, Walter asked what I was doing in the city, and when I told him, he said, “Well, I don’t see you becoming the next Susan Sontag,” then invited me to wander over to some LIC exhibit openings with him.

When I began collecting stories about the LES in the ’70s and ’80s—a sprawling, unfinished oral history for which I interviewed Walter again in 2015—he was incredibly supportive.

“I’m far too lazy for a project like this,” he said.

And, “I’m too shy to call all these people up,” he said, quick to pull out his phone to share contacts for subjects I wanted to interview.

When I occasionally ran into Walter at exhibit openings, he’d give me a cranky pep talk that vaguely had the tenor of a coach trying to motivate a lazy athlete.

“You gotta dig, really dig, ” he said.

“Are you still doing that thing? Keep going,” he said.

I didn’t keep going after about 2016.

I stopped writing about art, and saved the many hours of audio files I’d collected to a hard disk drive that went into a box of files I didn’t know what to do with, where it would remain for nearly a decade of life’s great ups and downs.

American poet Gertrude Stein said, “We’re always the same age inside” – awkward wisdom on mortality that makes me think of this story of Walter – the kid inside the ‘old man’ – newly arrived in New York, catching glimpses of the city through his eyes, looking past the ‘hill’ of Columbia, imagining what awaited him downtown.

Interview and editing by Rachel Dalamangas

WALTER ROBINSON:

You know there’s this notion that we know what we’re doing and we’re in control of our lives, but actually of course we’re not. We don’t know what we’re doing and we’re not in control of our lives. And how I ended up in New York I would say is just an accident. But there must have been something, some psychological thing.

Here I was in Oklahoma. Eldest son of a completely middle-class family. Typical angry, repressive, hard-working father.

And I could have stayed in Oklahoma and lived in Oklahoma and been bored, but somehow, I felt enough out of place unconsciously that I came to New York.

I came to New York in 1968. It’s not the typical story when people come to New York. Most people, you know, they pack their bags, and everything, you know? For me, eh, I just came for college and never left.

I was afraid of the city. You’re cloistered on the hill at Columbia at school and they would tell us, “Don’t go downtown. You’ll get mugged.”

I was really slow on the uptake. I discovered the art world when I was in college and started going to museums and started to go to galleries in SoHo and got caught up in the art business that way.

Where the Twin Towers stood it used to be nothing. It used to be a landfill. There was nothing there. It was like a beach. They’d do performance art there. Martha Wilson would curate it. I saw Sun Ra there.

When I got out of college and moved downtown, my rent was $220, and I think I had a job typesetting. Somehow I got into the typesetting business. Maybe it was freelance for Sing Out magazine. Or maybe it was part-time for this newspaper called The Jewish Beat. I made $6/hour, and I had more money than I knew what to do with.

By the end of the 70s in SoHo, there was this SoHo style painting. Painting that didn’t know what it was doing. Say the dean of SoHo painters was Ron Gorchov. That kind of abstraction. Judy Pfaff for instance is another. People who are still carrying on in abstraction even though it’s been bypassed by newer aesthetic developments.

In the early 80s, I moved to Ludlow Street, and I was hanging out with all my friends from Colab. I had a job. I worked at Art in America, and I guess I was looking for another extracurricular activity. I had been president of Colab and decided to quit I think in 1982.

I had my own painting by then. Now if I had been smart, I would have pursued painting 100%. That’s what I recommend to young people. Don’t get a job. Pursue your art 100%.

I was looking around for another project and somehow, I got the job of being the art editor of the East Village Eye. I guess Leonard asked me if I wanted to do it, and I said yes.

Carlo McCormick was already writing for them and that’s when I met Carlo. He was already writing about the piers. There were a lot of artists that would go over to the piers and insert artworks. I never even went over there. There’s this famous David Wojnarowicz painting of like a giant cow’s head with a tongue sticking out painted on a wall at the piers. They’re all marked out by now of course.

Self-Portrait (after Matisse), 2024

At the East Village Eye, we had a lot of fun writing nonsense.

I wrote a little review of a guy’s show just by looking in the window. I didn’t go in and look at the art and he got mad at me about that.

I had the whole Waltergate thing. You may know about Waltergate. When I stitched together a bunch of press releases and ran it as a column as if somebody had written it. The funny thing was that poor Barbara Gladstone complained and then the art critic Joe Matsheck who was a player in those days wrote in to support me. Judd Tully complained because he’d been misquoted. It was funny because Judd blamed Carlo because Carlo had written the column next to it. It’s all very confusing.

That whole [1983] Whitney Biennial was harshly criticized as being the “East Village Biennial.”

That’s when it became clear to me the scapegoat that the East Village was becoming for all things that people thought was bad about art. “The New Art’s too stupid or too gaudy or somehow meretricious.” “The East Village is only about money.”

Conservative forces, whether it’s Robert Hewes or writers for October magazine would attack the East Village and attack the Biennial as the East Village Biennial even though in fact there were only a few artists associated with the East Village in it. Most of the artists from the East Village have never been recognized by the museum structure.

The East Village represented these upstarts, these upstarts who are bad.

But you can’t say the same thing was true about Keith and Kenny and Jean-Michel. They were the triumvirate.

Keith was a star before anybody even knew who he was because he was doing his Radiant Child barking dog graffities all over on plywood in construction sites and on the subway and people really liked those. Even though there was a big graffiti movement, his stuff is really not that vandalistic. Like a lot of the graffiti writers would write all over the trains. So he was already very popular with the people.

And then when Jean-Michel had his first show, there was this intense buzz. Everybody loved that. Really came out with his first show at Anina Nosei in SoHo. Tremendous buzz about it. That was the show where he was supposedly locked in the basement and kept painting. Everybody just loved that stuff.

So Kenny’s adaptation of a Hanna Barbera look fit totally in with whatever it was that was happening this 80s – the American 80s painting revival.

It’s also part of the Tony Shrafrazi aesthetic.

Tony had a bunch of other artists that are kind of forgotten now. Like Brett De Palma, Ronnie Cutrone. I think what happened to Ronnie was that he wasn’t focused enough on the art business because he was too much of a drug addict. The art world can be harsh on people who are drug addicts, people who get a reputation for being junkies.

There’s nobody like Tony. He’s a little bit insane now, I think. He’s really enthusiastic about art. He’s very meticulous. That’s why he loves Jeff Koons so much. Because they share almost obsessive-compulsive meticulousness. Tony’s the kind of guy who has to have an assistant to wait around for him because he doesn’t really know how to lock up.

In the art business, you want to be known as the go-to person for something. The art world is full of go-to people.

You have to have your eyes on the brass ring and you have to go for the brass ring. You can’t be satisfied with sitting in the back of the background.

I was talking to a writer that used to work for me the other day. I had been looking back at my blog on Artnet from 10, 12 years ago. It was kind of like a diary. It seemed kind of like a waste of time, but really it was an investment in the future.

And I was saying to this young writer, “Why don’t you have a blog where you write once a day and post about what you saw or what you’re thinking about.”

But of course, when I was young, if someone said that to me, I would have thought, ‘I can’t do that. I don’t know what I think. I don’t know what to say.’

Now I’m old and I know what I think and I know what I want to say.

What I liked about Walter Robinson was that he was good at being dark. He would say things like, “We live in a world filled with resentment, racism, stupidity and hate. The consumerist utopia sells us on the idea that a better world is possible. All you need is a little dishonesty,” with a casual matter-of-factness that dared you to argue with him. For someone whose head was almost certainly a great aquarium swimming with art and the strategies of artifice, he also had that quality of obdurate journalistic loyalty to facts, reality, and truth.

He counterbalanced his grim outlook with a breezily playful and relentlessly deadpan sense of humor, so it was sometimes hard to tell when he was kidding or not—as when he “claimed as a figurative painter to have debuted in 1984 the first-ever painting of a nude flossing her teeth.” (Seriously, is this true? Where is it?)

His commitment to seeing things as he saw them and then saying out loud what he saw was inspirational, driven by sensitivity to the world rather than callousness. He seemed to recognize the necessity of seeing and thinking about the things that are hard to think about and see – and not just the things that are fun, sexy, and delicious (though much of all that made it into his repertoire too).

At zing, we join the art world in remembering Walter for his sense of humor, his insight, art, and words:

The Wallyburger

two-page spread from “Big & Beautiful”

In zing #23, curator Charlie Finch explained Walter’s paintings of fast food hamburgers, which he dubbed the Wallyburger, as so:

The Wallyburger becomes more excessive the more you examine its contents: drip equivalence achieves statis in the paint Robinson meticulously applies, the tomatoes rolling into cheese in the imagery and the automatic Pavlovian drool which ensues. Never underestimate the power of a burger, even a painted one. . .

The Fertility Painting

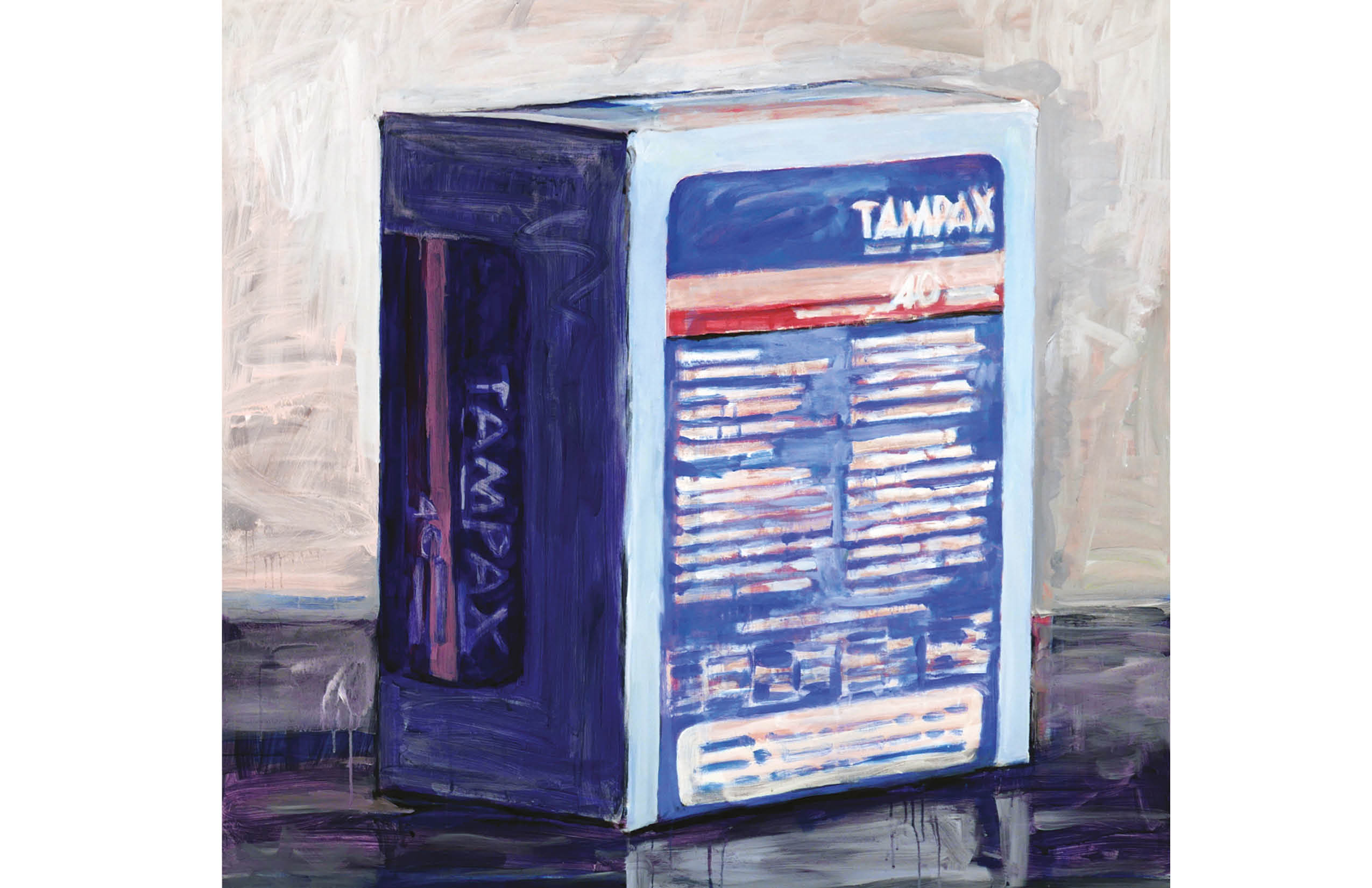

from Pharmaceuticals

Naturally, when Walter wrote his own curator’s note for a project of paintings he contributed to zing #25, it was a work of art unto itself, ending on this note:

The other works from that [Pharmaceuticals] show have found homes in important collections, thanks to Jeffrey Deitch, who included them in the survey of my work that he hosted at his gallery in October 2016. All save for the four-foot-square painting of a box of Tampax, that is. My ‘fertility painting’ I’m keeping for myself.

The Male Paintings

Oxford Dress Shirt Lands End, 2016, acrylic on paper, 12 x 9 in

When, in an interview for zingchat, Devon Dikeou asked Walter why he was painting so many shirts, he gave this as an explanation:

I paint a lot of sexy girls, in the studio I’m surrounded by images of women—you know, no one is really interested in men as a subject, not men OR women. But I felt bad, I don’t want to seem a complete dog, so I needed a masculine line, for balance.

So the thing about the shirt paintings, is that they’re MEN’S shirts, so they’re male paintings. What’s more, the images come right from the catalogues, or more typically from advertising emails, and the shirts are all flattened, folded and squared off. They’re pinned down, baby, can’t move at all. They’re just torsos, figurally castrated!

Not some kind of visionary

When I interviewed Walter in 2013, I foolishly prodded him, trying to get him to take a stance on real art vs commercialism or something silly along those lines, and instead he gave me this:

Early on I was interested in the idea of being straightforward and not pretending you’re some kind of visionary or something. It’s stupid. That’s my story and I’m sticking to it.

Lessons of New York is a collection of oral histories from the LES art scene of the 70s and 80s. This never before published interview was conducted November 2014 in NY, NY.

Diagram: “tag”, “throw-up”, and “piece” by Al Diaz

Amidst the dirty-glamour of the downtown art scene of the 70s and 80s, artist Al Diaz (b. 1959) formed the pen name SAMO with his classmate Jean-Michel Basquiat. Then a couple of unknown kids at City-As-School High School, the duo tagged the dilapidated streets with smart-ass poetry such as, “SAMO© 4 THE SO-CALLED AVANT-GARDE” and “SAMO© AS AN END TO BOOSH-WAH.” Their friendship would prove, like so many of Basquiat’s relationships, to be fiery and generative, driven by both fraternity and competition.

Interview and editing by Rachel Dalamangas

We were real cynical and rebellious kind of kids. Fuck everything kind of thing. Jean [-Michel Basquiat] felt that way. I felt that way. We were dissatisfied.

The 60s didn’t seem to accomplish anything. The sexual revolution. We were jaded. It was pre-AIDS so everyone was screwing around. We were just kind of a bored bunch. We rolled our eyes a lot. We didn’t have faith in much. The city was dilapidated. It was a time of mild hopelessness. And you’re at the age where you think grownups are a bunch of liars and everything is a lie.

We didn’t really believe in anything. Our lack of belief in anything was an alternative to belief in anything else.

We didn’t make “street art”. It was graffiti. The “street art” thing is a little more academic. You go out there with the intention of making art. Graffiti, in my generation, we weren’t trying to make art. I was trying to get my name around. I wanted to be famous.

Some people will do anything to get themselves noticed. Jean was like that. One time, when we were in high school, maybe the summer after, he painted his face silver and stood on the Brooklyn Bridge so people would look at him. He would take his overalls and cut a piece off so that you could see his crotch, exposing himself. Anything he could do to get someone to look at him.

When we started doing SAMO, it was almost competitive but a collaborative kind of thing. We wanted to keep the same handwriting. We had rules about it. We would practice it. We would look at stuff and write stuff together and try to keep the best stuff. We were editing ourselves. Both of us were lovers of language so we’d try to out-clever each other.

Yeah, we wanted SAMO to look slick and cool if that was so much high art but it was all about style and ego. Driven by that. The bottom line. Then it developed into making it look prettier and this and that. That was a gradual process. It didn’t start out as, “Hey, we’re making art here.” Nobody ever said that. Nobody ever said it was going to be a global phenomenon.

We also didn’t say it like, “We’re going out tagging.” We were paintin’. We were bombin’. And we’d tag something. The i-n-g of it didn’t come until later, if that make sense.

SAMO was only me and Jean though. People would try to copy it, but it was only us. We were a little bit Nazi about it. We were possessive.

It was crazy. It was a fun time. It was a hedonistic lifestyle.

I remember one time, I was at Tier 3 and they had just changed the policy. They had just started hiring some bouncer type door people because before everyone would just walk right in. And Klaus Nomi was standing in front of me waiting to get in.

When he gets up there, the guy says, “Alright, $10.” Like a big gnarly dude. Probably a Hell’s Angel.

And Klaus goes, “You don’t know who I am?”

The bouncer goes, “I couldn’t give a fuck who you are. Give me $10.”

It was so fucking hilarious because he was so incensed and the guy couldn’t give a fuck.

I didn’t really know Klaus at all though. He was just around with all those other people.

I was very salt of the earth. I didn’t have crazy hair. I wasn’t trying to be fabulous. People like that kind of intimidated me. Jean was very good at that, looking like completely insane. But I was from the Lower East Side, working class kid. I really wasn’t trying to do any kind of like expression with my clothing.

I screwed around with some of the girls that were all costumed out and stuff like that, but I was kind of very street. That kind of set me a little bit apart.

I knew Keith [Haring]. I thought he was a very smart guy. Very ambitious and very focused on what he was doing, but he could be a little catty. I remember one time he said, “Al Diaz is a dabbler” and he didn’t even know my history.

He just said some bullshit. Because I was no longer doing SAMO? Because Jean was saying something about me to him? Jean was saying some nasty stuff about me for a while until somehow we became friends again.

After ’78 until at least 1980 we went our separate ways.

When he took the SAMO, because it got some media attention, he was using it as a springboard for his career. It was no longer SAMO. It was Jean.

We had gotten that article in the Voice recognizing us so he just rode that but I had nothing to with that. I had been as much a creator of it as him so I had some resentment about it.

After the SAMO article in Voice we dropped off. It was over some stupid shit. We had this place where we worked for this guy. A white metal casting shop on Spring Street. He would work there anytime he ever needed a few dollars.

So one day we were in the shop and we found this figure of a Buck Rogers. Remember those little green plastic soldiers? It was kind of like that, but it was Buck Rogers holding a ray gun with a helmet.

He said, “Wouldn’t this make a cool pin.” Kind of a brooch.

So I was like, “Yeah, yeah, that’d be cool.”

Then he vanished for a while and I ended up making the pin because I was making pins and selling them. I had my little industry going.

When he found out I was making the Buck Rogers pin he flipped out. He was so incensed and that was it. It was over some stupid shit like that.

It broke my heart. He had like zero skills for dealing with conflict.

He was an amazing human being because his head was in all these places. You’d never see him reading so it’d be like, “Where’s he getting all this information?”

Nobody really thought we were gonna be famous. Well, Jean did. Jean knew he was going to be famous. I’m sure Keith did too.

The night we hooked up again, he told me that. I hadn’t seen him in like two years and he told me he was working on that film Downtown 81 and then we tripped that night.

We tripped that night and walked around the West Village and we kept finding joints, like four joints, like someone had dropped them like one by one. We were spouting, babbling, and one point, we were sitting in Sheridan Square, and he turns to me and he says, “Al, I know I’m going to be real famous and I’m going to die young.”

What do you say to that, right?