A soft collision of ancient glam and sexy ruin marks the recent collaboration between Julia Rose Katz and Devon Dikeou—both recipients of the 2025 Rome Prize in their respective fields: Julia, winner of the Anthony M Clark Rome Prize for Renaissance and Early Modern Studies, and Devon, the Jules Guérin Rome Prize for Visual Arts.

While on fellowship at the American Academy in Rome (AAR), they were paired in a program called Shoptalks, a public forum for Rome Prize Fellows to share their current and ongoing work with each other. The result of their working in collaboration was an idiosyncratic limited-edition book of images sourced from Renaissance paintings, Ancient Roman sculpture, film stills, fashion, and photography as well as their own photographs and artwork. The only text that appears are statements from Julia and Devon, and chapter headings: Entrance, Break, Pop, Part, Joy, Rock, Exit.

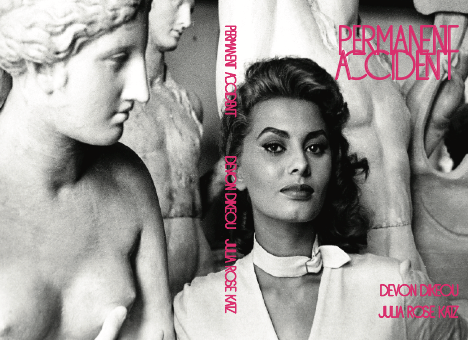

Permanent Accident—a seemingly enigmatic title that was taken from a glitter spill in the studio—is both artwork and book, and one look at the cover alone tells you everything you need to know about how to read it: a young Sophia Loren posed next to a Roman statue, looking with catlike self-possession directly into the camera as she sneaks one hand toward the statue’s breasts as if to make a grab at them.

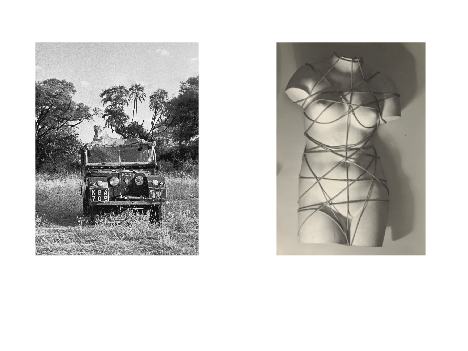

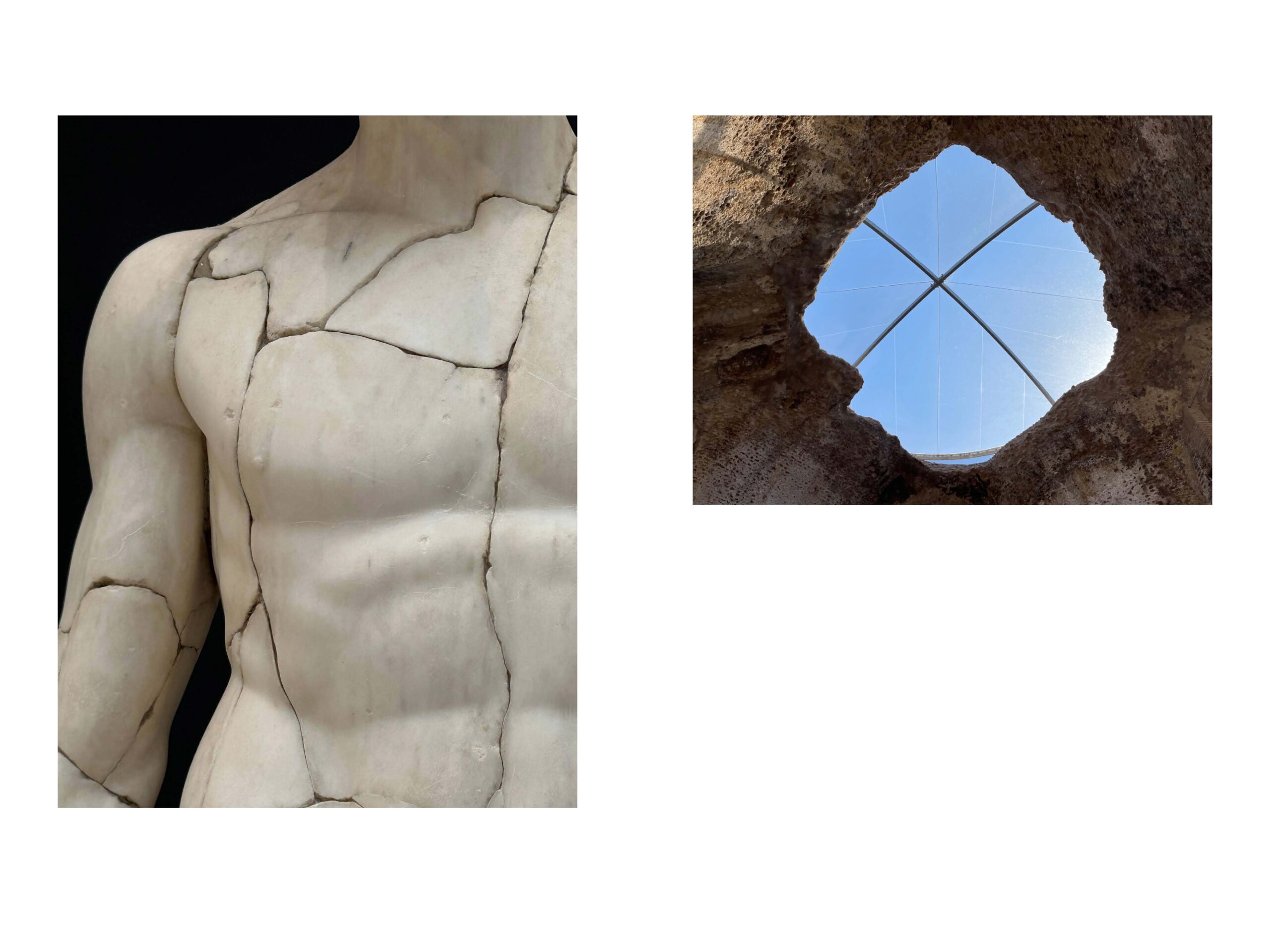

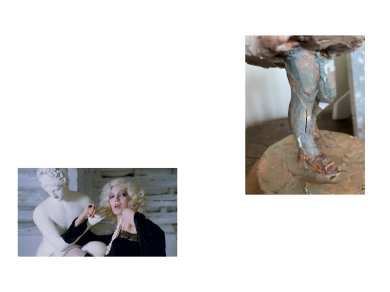

Which is to say, these images talk to each other—fractures appearing on the torsos of figures amidst ancient ruins, a Saul Leiter photograph of a woman examining cracks in the sidewalk, doorways and gates to devotional altars. It’s more poetry than narrative, more art than history, more history than narrative.

In conversations leading up to their Shoptalk, they realized that they shared a connection to artist Lizzi Bougatsos–Devon as the largest collector or her artwork, and Julia whose work is influenced by personal experiences that evoke themes of breakage and repair as well as the use of found objects, also characteristic of Bougatsos’ work. As part of their Shoptalk, Devon brought Self Portrait, a mold of Bougatsos’ leg in ice to the entrance hall of the Academy.

Devon Dikeou & Julia Rose Katz

as Interviewed by Rachel Dalamangas

During your AAR Shoptalk where the book-in-progress was presented, I noticed the concept and references of breakage and repair in the sense of (art) restoration, the body, and even the way that the images are presented breaks their original framing. How does the title Permanent Accident apply to your contributions to the book? How was the title decided?

JRK: We came up with the title together over a meeting in Devon’s studio. I mentioned loving the glitter that covered a book layout displayed on her table. Devon told me she had mistakenly spilled glitter all over the studio, and that it had become “the most beautiful permanent accident.” This was the genesis of the book’s title, but it does have a deeper meaning too. The idea when compiling the book was to convey a sense of randomness, so the selection of images appears almost accidental. Of course, it is not actually accidental at all, but we wanted it to feel that way. In reality, the images are carefully chosen, organized, and arranged, but we intended the rationale behind the selections to be invisible.

DD: Another title could be Invisible Accident. Invisible and Permanent are diametrically opposed. One must look, truly look, not just glance, to see. Sounds a little too phenomenological but it’s relevant. When Cezanne is looking at those oranges and realizes the next time he looks, they won’t be the same . . . It’s both a still life and a phenomenological realization that brings on Cubism. (Cezanne’s Doubt, Maurice Merleau-Ponty). We look at that glitter, hoping it stays permanent. “All that glitters is gold”, right . . . But that glitter from a second ago will float . . . As glitter does, and become slightly lost in the diaspora of life. Invisible, I know the invisible, the back door, the place uninhabited, the forgotten and yet treasured . . . The land of misfit toys . . . to which I most belong. And I would hope my compatriot and foil in glitter among all things to be there: Julia . . . Who knows the permanent.

It interests me that you both work across disciplines as creative thinkers: Julia as an art historian and artist; and Devon as an artist, curator, and editor. How did your backgrounds inform the creation of the book?

JRK: I don’t consider myself an artist. My interests are curatorial, so I treated the book as a curatorial project. I considered each image an object, situated in relation to what precedes and follows it. We each provided half of the images in the book, and my contributions comprise my own photographs, as well as found images that relate to the book’s themes and my personal interests as an art historian.

DD: I am an artist. But my practice encompasses both editing/publishing zingmagazine, a curatorial crossing, (est 1995 Ongoing) and collecting and assembling the Dikeou Collection (est 1998 Ongoing) . . . All three of which are very much curatorial by nature. And curating is a collaborative endeavor . . . In my mind, Julia and I set out on an adventure, initially on the platform of a book. But deeper than just the book, our collaboration took on another voice in the making of Shoptalks: and that was doing a real event, a real and literal presentation of our thought process. That was bringing in an ice sculpture by Lizzi Bougatsos from Dikeou Collection. It’s a leg, Lizzi’s leg, and the sculpture lasts about four hours. In the end, it can/needs to be broken. Inherent Vice. Its own medium is the cause of its destruction. So both the book and culminating moment of the performance were an exchange of ideas and images, thoughts, hopes disappointments and eventually . . . As that’s always what happens with books and performance, it’s finished, and once the exhilaration of the publication has been exhausted, there’s that . . . And performance is that friend dusts at the bar. Sometimes you may reunite . . . But books live on in their small capacity beyond the life of a show/exhibition/performance . . . Those sage words were spoken to me Kenny Goldsmith as I was delivering zingmagazine to Paula Cooper, which at the time, I knew will never get to her . . . Solice . . . Scott Joplin chimes in, with poetic and clear love of just trying to create, collaborate, and communicate . . .

It seems to me that there’s a kind of conversation taking place between images that I can partially understand just enough to follow a pattern although I am also unsure how much I’m projecting meaning (like being an American with very little Italian in Rome!) The images also cover a lot of art-historical-cross-disciplinary ground including ancient statues, fashion, black and white film stills, pop, and contemporary art (including your own). Can you share some insight on your choices of images and how the book was arranged?

JRK: If you’re projecting meaning, then you’re responding to the book exactly as you should! Sometimes our approach was more aesthetically driven, other times it was more playful. It was very important to us that the images in each spread converse with one another, but it’s your job as the reader to uncover the hidden significance. My work as an art historian focuses primarily on ideas of bricolage—the combination of ancient objects into new compositions—all of which directly inspires and informs the assembly of images in Permanent Accident.

DD: Sections: we divided the book into sections/chapters with input from both of us in terms of both image selection and placement under section titles, and then as a juxtaposition with each other. Those section titles we settled on are: Entrance, Break, Pop, Part, Rock, Joy, Exit. If a reader finds a clue here or there, by chance or projection, we might create a memory, a pretty important exchange between reader, curator, editor, artist, and audience.

Ok, very simple and yet very hard question: How does one “read” this book? It’s interesting because the images are all out of their original contexts (your studio art, reproductions of museum objects, and gallery pictures), and the book itself is a new original work of art. In a way, it only makes sense for it to exist as an actual object (and not an ebook) in a time where content is getting hoovered up by the great maw of the internet, which tells me physicality, especially regarding how the images are presented in a two-page spread, matters a great deal here.

JRK: Yes, this is absolutely correct. The book would not work the same way in a digital format. The tactile experience of holding the book, flipping through its pages, and engaging with it as a physical object is crucial to our conception. We live at a time when we are inundated with images, and our intention here was to bring value and focus to each page. Our hope is that the reader brings their own meaning to these visual compositions by montaging together disparate elements.

DD: Reading is subjective. Of course, Gertrude Stein and more recently, Calvino, Kundera, Cortazar, Auster among others teach us this. The reader in the postmodern world, much less the universe of magical realism, is an active reader, who participates with their interpretation of the published work and goes down whatever rabbit hole that may lead. I hope it’s a good as Alice’s, which is both real and unreal.

I LOVE the cover of Sophia Loren in Rome with the statues and of course it’s very clever the way the image wraps around the cover. It winks at the sense of humor and playfulness you both brought to this project. Even the decision to use “shocking pink” for the cover text teases out a little bit of scandalousness and sexiness, and no small amount of glam and feminine confidence. How did you arrive at the truly brilliant choice of using this particular image?

JRK: We were perusing photographs of old film stars and came across this shot of a young Sophia Loren surrounded by casts of ancient sculptures. The image relates to my academic work on the revival of antiquities in Italian cinema and our common interest in popular culture, specifically the women who defined that culture in the twentieth century. The use of the color “shocking pink” for the text draws on the history of the color by Elsa Schiaparelli, who adopted it for her brand and for the packaging for her perfume, designed with a then scandalously shaped bottle that recreated Mae West’s torso. “Shocking pink” became representative of female strength as well as the avant-garde in fashion, and this 1930s history inspired us as we developed the book, which aims to confuse or shock with its sometimes unclear juxtapositions.

DD: Sophia is there, present in all of Italy. Not like how you might see her in little Italy. She’s just there, permeating the air and telling you she is its ethos . . . Choosing the cover is perhaps the most important task of editors/curators . . . In the same way when I select a cover zingmagazine, where I go is to the NY Picture Library, and physically going to the building, and search specific topics, in folders, under the fluorescent lights for something in the long lost selection of images by some picture editor/librarian—nameless—I might find an image that might pertain to that which should be conveyed. But Rome itself is a library. A visual, architectural, filmic library and as you peep, revere, absorb . . . Sophia shines bright . . . Coddled in and next to the gods, drinking their nectar, how could you resist. Why shouldn’t she take Front, Back, and Spine.

Rachel Dalamangas

New York, New York

September 2025

Image Credits:

Man Ray

Lina Mertmüller

Deborah Kass

Luigi Ghirri

Patricia Cronin

E.V. Day

Hiroshi Sugimoto

several photos taken by the authors

Devon Dikeou and Julia Rose Katz

Sophia Loren at a studio in Rome, 40.6 x 26.7 cm © Science History Images / Alamy Stock Photo.

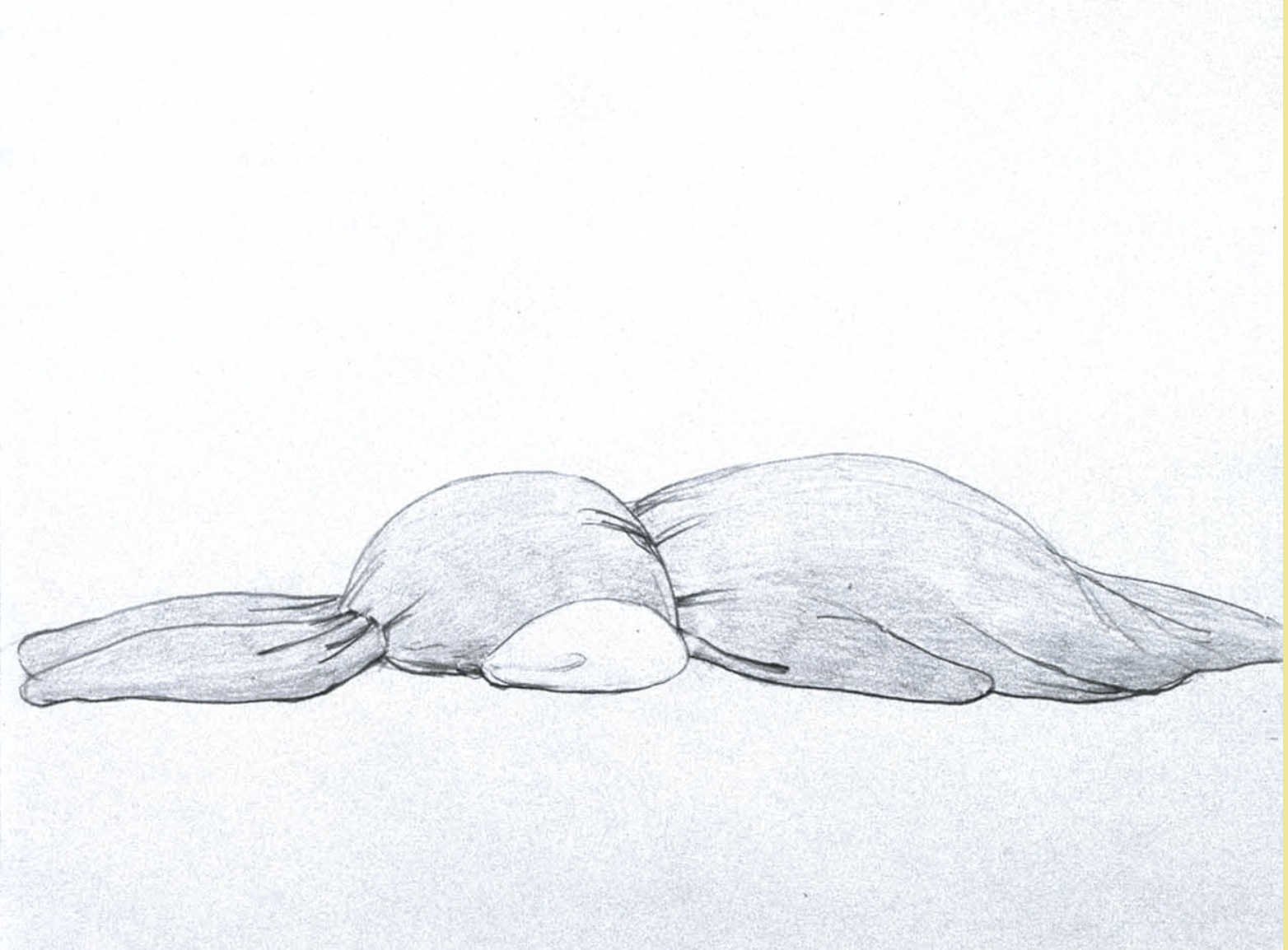

Elsa the lioness of Born Free fame lying on the roof of the Adamson’s Series 1 Landrover, Kenya. 26.5 x 34.5 cm, 2018 © Mark Boulton / Alamo Stock Photo.

Man Ray, Vénus Restaurée (Restored Venus), 1936. Gelatin silver print, 16.5 x 11.4 cm (6 1/2 x 4 1/2 in) © Man Ray Trust ARS-ADAGP.

Deborah Kass, Blue Barbras (The Jewish Jackie), 1992. Silkscreen ink on syntehtic polymer paint on canvas, 91.4 x 114.3 cm. Courtesy of the artist.

Luigi Ghirri, Amsterdam, 1980, from the series ‘Still life,’ 2011. Blue felt-tip pen on paper, 75 x 56 cm (20 x 24 in). © The Estate of Luigi Ghirri. Courtesy Thomas Dane Gallery, Matthew Marks Gallery, New York and Los Angeles, and Mai 36 Galerie, Zurich and Madrid.

Patricia Cronin, Shrine for Girls, Venice Saris, 2015. La Biennale di Venezia, 56th International Art Exhibition. Photography by Mark Blower. Courtesy of the artist.

Luigi Ghirri, Pantheon, 1982. Vintage chromogenic print, 32 x 47 cm (12 x 18 1/2 in). © The Estate of Luigi Ghirri. Courtesy Thomas Dane Gallery, Matthew Marks Gallery, New York and Los Angeles, and Mai 36 Galerie, Zurich and Madrid.

E.V. Day, Bombshell, 2000. Dress reproduction of Marilyn Monroe’s costume in the film “The Seven Year Itch,” 16 x 16 ft. Collection of the Whitney Museum of American Art. Courtesy of the artist.

Hiroshi Sugimoto, Teatro Carignano, Torino, 2016. Gelatin silver print, 1492.2 x 119.4 cm (58 3/4 x 47 in) © Hiroshi Sugimoto. Courtesy Fraenkel Gallery, San Francisco Lisson Gallery.

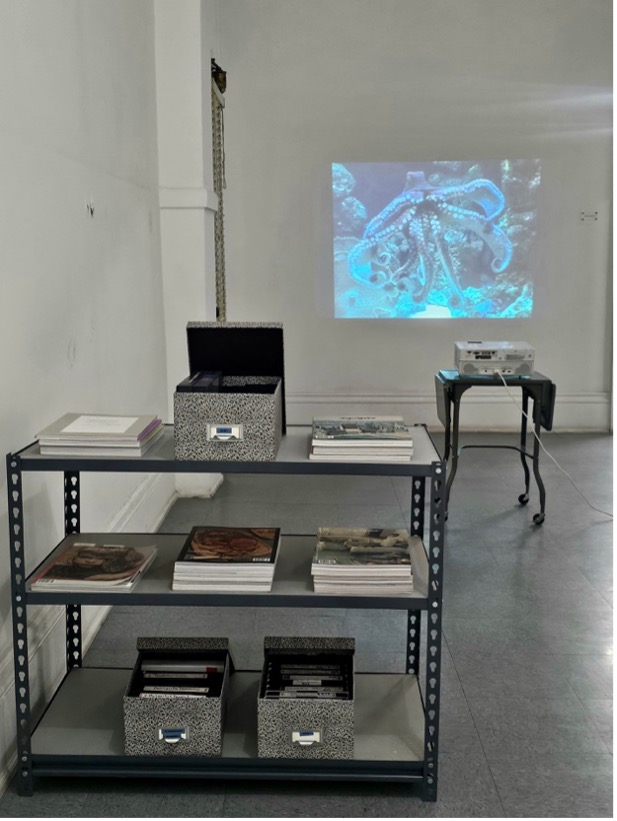

This July, Denver’s Month of Video (.MOV) returned with its second citywide iteration, transforming nontraditional spaces into screens for experimental film and video art. Among the standout contributions was “Moving Still: Video Art Highlights from the Dikeou Collection,” a layered exhibition embedded within Devon Dikeou’s sprawling “Mid-Career Smear” retrospective. Curated with intention and wit, “Moving Still” explores how video inhabits—and disrupts—space, stillness, and perception. Featuring works by Momoyo Torimitsu, Serge Onnen, Dan Asher, and Dikeou herself, the exhibition examines themes of capitalist spectacle, ambient media noise, and ecological elegy, all while mining the slippery terrain between fiction and reality. Here, we talk with the Dikeou Collection director and curator of “Moving Still”, Hayley Richardson, about the selection process, the political charge of background visuals, and the surprising archival discoveries that deepen the show’s resonance within both the Dikeou Collection and the broader .MOV program.

Hayley Richardson as interviewed by Rachel Dalamangas

Serge Onnen, Break, Cell Animation DVD with Sound, 2:11 minutes, edition 1/5; Serge Onnen, Silence Fence, Wallpaper Designed by Artist

Devon Dikeou, Entertaining is Fun—Dorothy Draper, 156 Scott Toilet Paper Rolls, Unrolled to a Diameter and Stacked to Attain the Height of the Artist

How did you decide on which video works to include from the Dikeou Collection’s roster, particularly those by Devon Dikeou, Momoyo Torimitsu, Dan Asher, and Serge Onnen?

“Moving Still: Video Art Highlights from the Dikeou Collection” exists as an exhibition within an exhibition, as it comingles with Devon Dikeou’s “Mid-Career Smear” (MCS) retrospective. When asked to participate in Denver Month of Video (.MOV) by organizers Jenna Maurice and Adán de la Garza, the plan was to highlight as much video art represented in Dikeou Collection as possible while maintaining a flow and cohesiveness within MCS.

Most of the video artworks in the Dikeou Collection are part of multifaceted installations with various media, and it was crucial to have these installations exhibited in their entirety. This was not viable for certain artworks, but I was able to achieve it successfully for Serge and Momoyo. Serge’s video Break is accompanied by wallpaper of his own design, which is permanently installed in the Women’s bathroom, so it was easy to incorporate his video within its preexisting context. Momoyo’s Miya Jiro combines video, sculpture, and photography, and is installed in the same room as Devon’s We’d Like to Get to Know You where the entire room is covered wall-to-wall, floor-to-ceiling in business cards. Considering Miyata Jiro is about business and has a businessman crawling on the floor, it was a perfect match and one that will likely remain permanent. Dan Asher’s Creature and Devon’s The News Too are standalone pieces, so their inclusion and placements were more straightforward within the context of MCS.

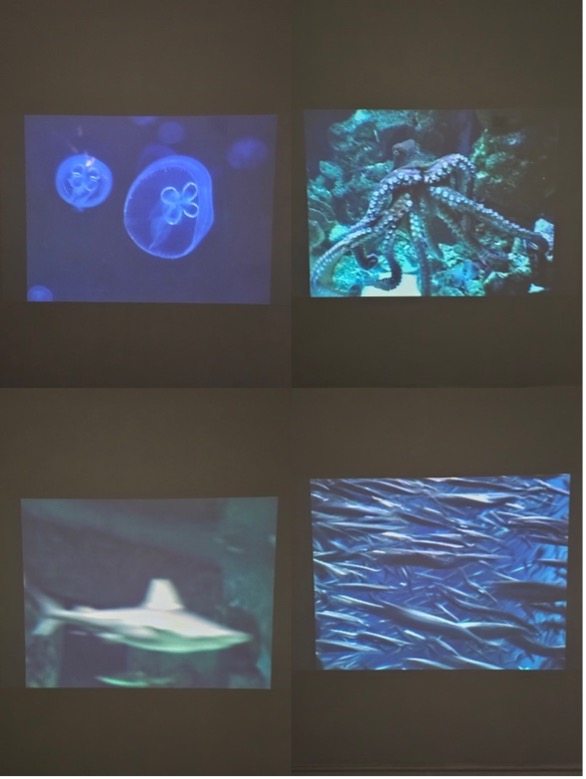

Dan Asher, Creature, Stills Showing Jellyfish, Octopus, Shark, and Sardines, DVD Projection, Variable Dimensions

With works spanning from the mid 1990s to recent pieces, are there overarching themes or threads—such as stillness, media critique, or sensory perception—that unify the works in this exhibition?

Serge’s video is about animation’s power to make the most impossible situations become real, and the ubiquitous yet ephemeral nature of drawing. Momoyo’s work explores the tension of reality and authenticity in a capitalist society, and her videos are documents of an unsuspecting audience experiencing that tension in real time. Devon’s video removes the bias and the blabbering of cable TV news and allows the repetitive stillness of the background to create harmony in a fractured, media-obsessed nation. And Dan’s projection of sharks, fish, octopus, and jellyfish floating in water transports the viewer to a peaceful, meditative underwater world . . . but the reality is these animals are in captivity at the London Aquarium as their natural habitats grow more dire and scarce by the day.

So, a unifying thread is suspension of reality. Our fixed perceptions become malleable when experiencing these works—fiction becomes fact and vice versa.

Devon Dikeou, The News, Series of Fully Operational New York City Newspaper Dispensers, Available for Viewers to Use for the Duration of the Exhibition, Papers Updated on Daily/Weekly Basis by Appropriate News Agencies

Devon Dikeou, The News Too, Background Graphics of 9 Popular American Cable News Broadcasts, Looped After 5-Minute Duration, Variable Dimensions

Could you speak to Devon Dikeou’s piece The News Too—how it distills network news into ambient visual noise—and its significance within the show?

In order to talk about The News Too (2019 Ongoing), I need to talk about its sibling, The News (1992 Ongoing). Nearly all of Devon’s artwork is dated Ongoing due to each piece’s nature to grow, expand, and take on new meaning within every new context and interaction, but this is one of the few works in her practice in which an “updated” version is born from a pre-existing artwork.

The News is comprised of eight NYC newspaper machines. When originally shown in an exhibition called “Certain Uncertainty” curated by Kenny Schachter at Deutsche Bank, each machine received its regular daily or weekly delivery of newspapers. The exhibition title was apt for this installation, as the news is a type of certain uncertainty.

The News Too exists as a video installation where the backgrounds of nine American cable news shows are arranged in a grid à la The Brady Bunch. Some backgrounds are animated with waving flags or swirling stars; some are still graphics of grids and panels. Some display the name of the show and/or host, some are anonymous. The backgrounds play for 5 minutes before the final frame appears displaying the name of each show and then loops and plays again. This presents an interesting contrast with The News, in that it does not share any news at all. There is no certain uncertainty. No Left vs Right. The diabolical squawk box that is cable news is now patriotic ambience, swathed in stars and stripes, and red, white, and blue.

As for its significance in the show, it is worth noting that The News Too has been on view at Dikeou Pop-Up: Colfax since 2020 as part of MCS. Devon’s art practice has always been embedded within the curation of the Dikeou Collection, and since “Moving Still” exists in tandem with her retrospective, it made sense to include this particular video in the show.

How do you see “Moving Still” fitting into the broader scope of the Month of Video festival programming across non-traditional spaces and public screens?

.MOV is a true DIY endeavor. It was founded by artists with the goal to boost the visibility of video art through public art activations and artist-run gallery / programming spaces, all of which are free and open to the public. “Moving Still” is exhibited in Dikeou Collection, which is an artist-founded, free & publicly accessible non-traditional space. What sets this exhibition apart from other .MOV programs is that it highlights video artwork that is part of a private collection. While video has certainly gained traction among art collectors over the last 20 years or so, it still represents uncharted territory when compared to highly collected mediums like painting, photography, and sculpture.

Christian Schumann, Evel Machine, Painted Wood Kiosk Displaying a Still of “No. 2” by Sweden from zingmagazine Curatorial Video Crossing, vol. 2;

Devon Dikeou, City Gates, Room Installation of Security/Insecure, Security Secure, and Security/Kisosk, Variable Dimensions

The exhibition features compilations from zingmagazine’s Curatorial Video Crossing and early Zapp Magazine. What role do these curatorial projects play in dialogue with the individual artists’ pieces?

Like The News Too, the zingmagazine Curatorial Video Crossing videos were installed at Dikeou-Pop: Colfax as part of MCS. The videos are presented within a kiosk painted by Christian Schumann, which was part of another collaborative art project called Evel Machines Devon helped organize in collaboration with Mike Brown in NYC in the 90s. Artists Rachel Harrison, Ricci Albenda, Kenny Schachter, Lee Stoetzel, Rainer Ganahl, and Schumann were commissioned to customize these kiosks and have them placed in NYC businesses like Naked Lunch, SoHo Grand, Family of God, and The Void where they served as informational booths with local recommendations for bars, restaurants, hotels, galleries, museums, clubs, and other cool spots in the neighborhood. For “Moving Still” I decided to place the kiosk in proximity to Devon’s City Gates to give it that New York on-the-street feel as part of its original conception.

Considering the potent overlap between Devon’s art practice, art collecting & curating, and editing & publishing zingmagazine, it was impossible to ignore the relevance of the zing Curatorial Video Crossing project she initiated in the early 2000s for this exhibition. There’s a total of 42 videos across all three compilation volumes, and several of the participating artists are represented in Dikeou Collection, such as Dan Asher, Marcel Dzama, Sebastiaan Bremer, Lisa Kereszi, and Rainer Ganahl. The zing videos allow for more Dikeou Collection artist representation in the exhibition which was important for me.

Zapp Magazine, Issue #01, March 1994

Devon Dikeou, “Out, Out, Damn Spot” – Macbeth, Shakespeare, Happening Professional Waiter Serving 300 Warm Towels to Viewers, Who Enjoyed, Used, and Discarded the Towels, Variable Dimensions

Zapp Magazine was a surprise discovery when digging through the collection’s archives in search of more video treasures. I spent about a week watching all the artist tapes and DVDs I could find. I saw a lot of weird, wonderful stuff, but the decision to include Zapp Magazine was immediate because it shows Devon’s Out, Out, Damn Spot – Macbeth, Shakespeare performance installation when it was exhibited in “Bodyguard” at Hohenthal und Bergen Cologne in 1994. Out, Out, Damn Spot is currently on view in MCS, and the video is placed within that installation. For context, Zapp Magazine was an international videozine distributed on VHS from 1993-1999 that presented “exciting developments in contemporary art through registrations of shows, performances, artists’ video’s, interviews etc.” While the presence of Devon’s artwork on this particular tape was the main reason I decided to include it in the exhibition, Zapp Magazine really was on the cutting edge of collecting and compiling video art, interviews, and exhibition documentation in a cohesive and serialized format. These tapes are rarely shown in public and are not digitized, so I am grateful to share this work.

As far as the dialogue between the compilations and the individual artist videos, I’d say it’s about camaraderie, variety, and providing a different viewing experience for the audience. As previously mentioned, there are Dikeou Collection artists represented in the zing compilations, and, additionally, there are several artists in the Zapp videos who have affiliations with zingmagazine like Vito Acconci, Janine Antoni, Karen Kilimnik, Richard Agerbeek, Simon Bill (also a Dikeou artist), Sarah Morris, and Raymond Pettibon, among others. The overlap between all the artists among different projects and platforms is boundless. I love discovering these connections and I hope that resonates with audience as well.

Momoyo Torimitsu, Miyata Jiro, Mixed Media Robotic Man, Six Performance DVD Videos, Variable Dimensions

Devon Dikeou, We’d Like to Get to Know You, Business Cards, Variable Dimensions

Dikeou Collection is right at home in this neighborhood of cross-pollination between media, platform, content, etc. Can you share some of the cross-conversational elements of the video art exhibited at Dikeou Collection and corresponding zing projects and archival items?

Yes! The videos by Serge Onnen and Momoyo Torimitsu are part of expansive installations that represent other aspects of their artistic output. This is a central tenet to Dikeou Collection’s approach to collecting—to collect an artist’s work in breadth and in depth so we can exhibit the full range of their practice. Momoyo’s Miyata Jiro is, in my opinion, one of the strongest examples of this approach in the collection. The nexus of the artwork is a performance in which Momoyo took the Miyata Jiro robot to six major tourist and financial districts around the world and had him crawl through the streets while she, dressed as a nurse, tended to him along the way. The six videos in the installation serve as performance documentation, as does the photograph from the New York performance. Then, of course, there is the robot itself on the floor . . . all of which is now set in relation to Devon’s We’d Like to Get to Know You. So much cross-pollination happening in just that one room!

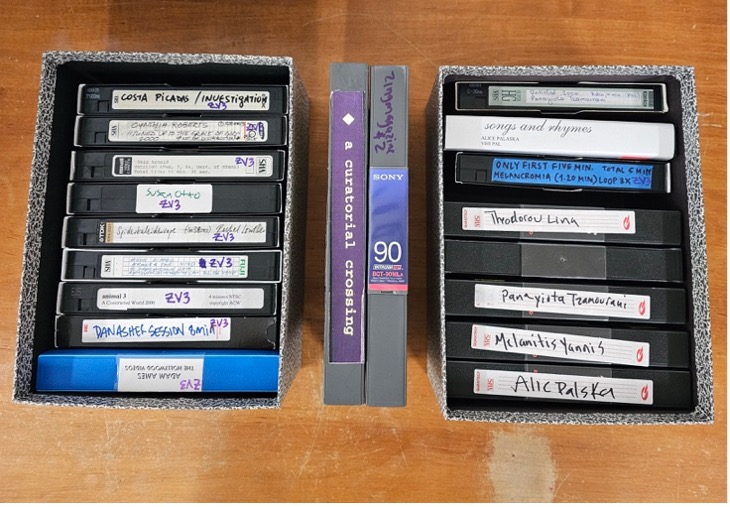

Various Artists, VHS Tape Submissions for zingmagazine Curatorial Video Crossing and final master tapes on Betamax

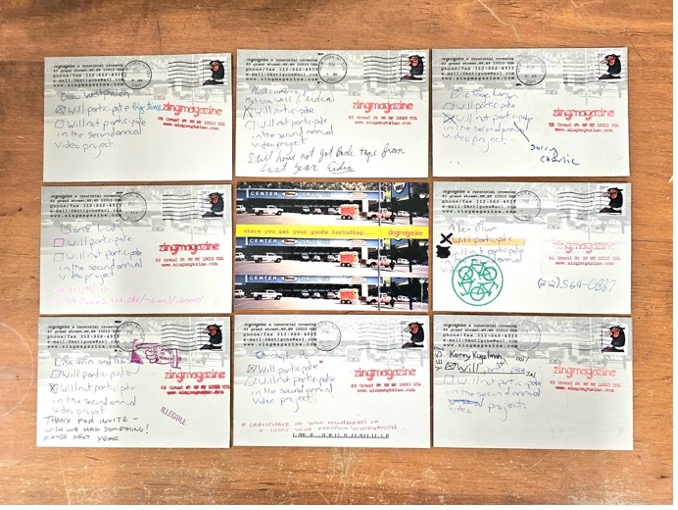

Select Postcard Requests for Submission for zingmagazine Curatorial Video Crossing

Another unique feature of the “Moving Still” exhibition is the inclusion of archival elements of the zingmagazine Curatorial Video Crossing videos. The extensive archives at Dikeou Collection open the doors to a deeper understanding of the magic that happens behind the scenes in the studio, at the collection, and at zing HQ. During my archival deep-dives I found the original VHS tapes submitted by the artists for inclusion in Curatorial Video Crossing. These individual tapes were compiled into master tapes on Betamax, which are displayed in the exhibition. One of my favorite discoveries in the archives was a batch of self-addressed & stamped postcards sent from zing HQ to dozens of artists requesting their participation in the Video Crossing project, with two handwritten checkboxes for “Will Participate” or “Will not Participate.” The cards reveal the DIY-ness of it all, and the intimate relationships between artists. Each one is personal and delightful.

zingmagazine Curatorial Video Crossing archival display with VHS and Betamax tapes, postcards, and zingmagazines; Dan Asher, Creature, DVD Projection

The zingmagazine Curatorial Video Crossing videos emphasize the magazine’s ability to extend beyond the printed publication, but the magazine itself has featured numerous projects that pertain to video, film, cinema, moving images, or images viewed on a screen or some kind of projection. I went through every zing project, bookmarked the ones that fell into those categories, and included them in the archival display. Some of the strongest examples of these projects include Susan Robinson in issue 1, Tamas Banovich and Brendan Quick in issue 2, Jonathan Horowitz in issue 3, Rachel Harrison in issue 4, Neil Goldberg in issue 6, Jane Hart in issue 15, Drazen Bosnjak in issue 18, Alix Lambert’s project in issue 24 as well as mine on Harry Smith, and Maria Antleman’s project in issue 25.

Researching and incorporating archival ephemera and artwork that addresses video in a printed format was my favorite part in organizing this exhibition, and, I think, a distinguishing characteristic of “Moving Still” within the .MOV landscape.

Rachel Dalamangas

New York, New York

August 2025

from zing #15, Momoyo Tormitsu “somehow i don’t feel comfortable”

What could artistic commentary on the Japanese commercialization of cuteness at the turn of the millennium predict about the state of the world in 2025? In some respects, quite a lot.

Momoyo Torimitsu debuted the iconic installation somehow i don’t feel comfortable, two inflatable pink bunnies scaled so that they appear cramped and uncomfortable in a gallery exhibition space, in Paris in 2000. It was a year when the texture of reality had already begun to feel slightly fake – often, if not always – in a fun way, so long as you didn’t look closely enough to notice the brewing problems that would only become more complex and dire in the coming quarter century.

Some other interesting things that happened the same year:

You could wait for your grandmother’s flight at the gate instead of beyond a ticketed obstacle course.

Cellphones and wi-fi were still rare and quasi-futuristic.

Social media didn’t exist (though AOL chatrooms did).

4chan didn’t exist yet.

Incels did, but in their gentler, mostly feminine, original form.

Jeff Bezos founded a private spaceflight start-up; Katy Perry released a debut album of unremarkable Christian music.

Peter Thiel was spinning Roth IRA straw into gold.

Donald Trump soft-launched his political career.

Vladimir Putin became president of Russia, then cautiously projected to be on a path of democracy.

Al Gore, winning the popular vote on an environmental platform, conceded the presidency to George W. Bush, who expanded foreign oil investment—widely seen as a sign of democratic stability in the U.S.

Britney Spears and Justin Timberlake graduated from high school, and publicly announced they were bf/gf.

See more from ‘somehow I don’t feel comfortable’ in zing #15 here.

No Poem Animation

Elegiac as well as strangely hopeful, director Catherine Gund’s docu-poem, MEANWHILE, which premiered last year, has been one of the only things in recent memory that I have found soothing about the nature of humanity and the future of the world.

In close collaboration with Jacqueline Woodson (text), Meshell Ndegeocello (soundscape), Erika Dilday (support), and M Trevino (structure), Gund made a living – breathing – film that captures quiet, reflective moments from six artists in NYC as they continue with their lives and work throughout the many crises faced worldwide 2020-2021.

The themes evoked in MEANWHILE – survival, life, empathy, resilience, identity – feel even more relevant and urgent in 2025. By the time I saw the film this spring, the first planes of kidnapped immigrants had landed in El Salvador, a good friend at the Institute of Peace had called me to tearfully recount being physically removed from her workplace, and the United States seemed then as it does now to be marching with horrific determination toward authoritarianism.

Where do art and artists fit in during times of crisis? The conviction that art should or even can make meaning from and has potential to impact minor and major events, essentially that art matters – evident in the making of MEANWHILE – is as instinctual and vital as breath itself. “I believe there’s no way to survive without art,” Gund says, and what’s so moving in MEANWHILE is that without preaching or platitudes or predictions based in false hope or the end of the world, are messages about what art has to do with living and staying alive, and creates a humanistic portrait of how to face struggle with both softness and grit.

Catherine Gund as Interviewed by Rachel Dalamangas

The title MEANWHILE is evocative of time both on the scale of history as well as human life, and even the fleetingly momentary. The word is also suggestive of simultaneous action, and at various times throughout the film is associated with poetic themes of respite, freedom, and breath. When and over what period of time was this film shot? How did the word ‘meanwhile’ shape your approach to storytelling?

The title MEANWHILE was the beginning — it came before the film itself. That word held space for what we couldn’t yet articulate. We were living in a moment where the future had no language. In the face of the pandemic, the uprisings, the collapsing of systems that were never built for everyone, we were suspended in a kind of breath. MEANWHILE gave us a way to speak, poetically, politically. It holds multiplicity: the passing moment, the lifetime, the historic scale. It reminds us that while one story is unfolding, another is too — parallel lives, joys, violences, resistances, all breathing side by side. And never all joy or all violence.

If we’re always in a state of tension and chaos, and that energy is always moving, maybe the problem is that I’ve tried to stay still inside of it.

Is there a way to do things differently or to imagine

differently or practice living differently?

I don’t know that the natural condition of life is a state ofrelief.

Natalie Diaz

The film was shot over the course of 2020 and 2021 — those ruptured, reshaped years — but it wasn’t a linear shoot. It moved like breath, in and out, across time and tone. That rhythm shaped the structure: six verses, each a different facet of how we live, how we resist, how we care for each other. Some days were cinema verité, some days were poetry. Some moments were built on rage, others on care. We weren’t documenting a crisis — we were existing through it and creating from within it.

The word meanwhile grounded us. It reminded us that every image, every voice, is in conversation with something larger — with the past that made this present, and the future we’re still fighting to imagine. This isn’t escapism. It’s simultaneity — a way of being present to contradiction, to multiplicity, to all that breathes at once. Even in grief, there’s beauty. Even in stillness, there’s movement. MEANWHILE is a refusal to flatten the moment into one narrative. It’s a way to hold complexity — to breathe inside it.

Shamel Pitts and Tushrik Fredericks

The film is formatted as a docu-poem in six parts. Did the author Jacqueline Woodson write the poem first and then the film was made, or was the film in progress and she responded to the footage?

Like the meanwhile, our film reveals synchronicity and simultaneity. We breathe to remember. We breathe to forget. The film began with Meshell Ndegeocello and me wanting to work together — to meld our associative, emotional, presence practices. Her sounds didn’t score the film; they scored the silence, the urge, the becoming. They created a space I could move inside. From those early pulses — breath and distortion, longing and loop — the film began to shape itself. Not in outline. In feeling. In time.

There was no sequence to our making. It wasn’t image, then music, then words. We were all inside the same storm. Meshell would send a sound, and I’d hold it up to the light of the footage. Jacqueline would listen, then speak a line:

“Like the newborn baby

who hasn’t yet heard the sound of her own cry,

we know, without the tears, that we’re alive.

We know long before we feel the pain of the outside world

that we are whole.

The fight already in our breath,

the fight in our hearts.”

Those words would ripple back to the edit, bend the image, slow the cut. We are born into interruption. Everything was responsive. We weren’t documenting — we were composing a present tense. Existing alongside.

The film unfolds in six verses. Not chapters. Not acts. Verses — because poetry was the only structure that could hold us, could breathe with us. Jacqueline didn’t write about the film; she wrote inside it. Her words were not commentary. They were blood and breath. Sometimes I would send her images pulled from her language. Other times, in the middle of this breath, this heartbeat, this fire, I would cut a scene just to leave space for a line to land:

“Even in the fire, we can’t extricate ourselves.

We’re all connected. Ancestors, aunts, uncles, children.

The blood that moves through our veins sings the same song —

a song we can pretend we don’t hear,

a song an inch away from our ears,

a song being sung always in the meanwhile.”

Everyone who appears in the film also creates from their own fire, their own heart, in an exchange that reverberates. We were finding a place where everyone’s path touches another — or doesn’t pass at all, but lingers nearby. In rehearsal, dancer Shamel Pitts says:

“There’s still this heat between us,

the sense of touch without touching,

and the heat that comes between this, from this —

and that we keep that alive.”

We weren’t illustrating a thesis. We were living a practice — of listening, of responding, of being changed by the work and each other. Nothing was finished until everything was. And even now, I don’t think of the film as complete. It’s still pulsing. Still saying:

“And we keep on keeping on

in all the ways, in always,

in all the spaces of time —

including in the meanwhile.

Meanwhile, we live.”

Juli Vanderhoop baking

The theme of breath is relevant both in the form of projective verse poetry as well as politically to the BLM movement, which adopted the last words of Eric Garner as slogan. Was this an intentional motif or one that arose organically through the process of making the film?

Breath was never a motif. It is the medium. Breathing is the pulse of the film, the rhythm that sustains and connects every frame.

This understanding didn’t begin as an intellectual choice — it emerged as a force, moving through us, through the footage, through the sound, through the words. Breath is political. It always has been. It’s the first act of life and the last. It’s the rhythm of survival — the breath that sustains, that resists, that says: I am still here, even in the face of forces that would seek to silence us.

In MEANWHILE, breath is the connective tissue — between image, sound, and word. It was the anchor of the time we were living in: the pandemic, where breathing became dangerous, measured, protected by machines; and the uprisings, where breath was denied. When Eric Garner said “I can’t breathe”, those words became a collective reckoning. We didn’t set out to make a film about breath, but breath insisted on being seen, heard, and felt. It rose up in Meshell’s looping, gasping, panting soundscapes; in Jacqueline’s verses, which returned, again and again, to one essential instruction: Breathe.

Breath is intimate. It’s ancestral. It’s violent. It’s liberating. We hear panting, inhaling, gasping, exhaling. We hear people breathing throughout the film. And the film breathes – expands and contracts, grips and releases – following the tension of our lives. Then quiet. This is the rhythm of the film’s structure – our fight to move through grief, through rage, through hope.

The film is about living in that tension. We breathe to remember. We breathe to forget. Breath is not just metaphor — it’s a condition of resistance and resilience. A refusal to be erased. A way of holding space for the past and the possible. It is the heartbeat of MEANWHILE, beating in rhythm with the ongoing fight for racial justice, for lasting freedom.

When Jacqueline says, “The fight already in our breath, the fight in our hearts,” she isn’t just talking about survival. She’s invoking the right to live fully, audaciously. To breathe freely and unapologetically is a radical act and I think of how breath moves invisibly, but always between us. How it connects us across time and struggle. How it carries memory. How it carries forward.

It’s the unspoken and shared, the invisible force that connects us across time, space, and struggle. It’s the space where our histories converge, where we hold each other in the weight of what we carry. Meanwhile, in the fire, in the heat, in the breath — we keep going.

Fire Dancers Animation

Questions about identity begin with the individual, and move outward into race and its constructs, questions about masculinity and about who gets to be American, and through the interconnectedness of New Yorkers going about the quotidian and quiet labor of an artist’s work, a portrait of humanity emerges. What was your approach to capturing that spectrum when choosing participants and how did you think about balancing the political with the deeply personal?

Identity is not a static form, a fixed shape; it’s a dynamic condition we inhabit. It evolves, stretches, contradicts, and becomes through our interactions, our memories, our exposure, and our familiarity. It’s not something we craft from a distance. It works on us, over time, through relation. And the questions it raises — about belonging, about freedom, about who we are allowed to be — are not theoretical. They live in our bodies, in our practices, in how we move through the world.

MEANWHILE was made with people I love, people I’ve been in conversation with for years — sometimes decades. Meshell. Jacquelin. Daniel Alexander Jones. Juli Vanderhoop. Dana Davis.

The film didn’t begin by assembling a cast. It began in community.

It began in trust. These aren’t interviews. These are continuations — of friendships, of artistic dialogues, of shared wondering, shaped over time. The people in the film are artists, yes, but they’re also thinkers, caregivers, visionaries. They’re in the middle of making something — not just a piece of work, but a way of living, of imagining beyond what’s already here.

We filmed across many places — Ohio, California, Massachusetts, New York — and what emerged wasn’t a portrait of place, but a portrait of relation. Of people listening to one another. Showing up. Risking being seen. The political and the personal were never separate — they’re part of the same breath. They shaped each other.

“We’re not always legible to one another… this idea

that something’s sort of hiding in plain sight, or that we can see

one another in lots of different ways — or not see

one another. I’m really interested

in that idea of degrees of not seeing.”

Teresita Fernández

That idea — of degrees of seeing, of allowing space for what can’t be named yet — became central. The film invites a kind of seeing that is slower, more generous, more curious. A seeing that doesn’t close down with certainty, but opens toward connection.

MEANWHILE doesn’t claim to define identity. It holds it in motion. It asks: What can we be, together, when we listen beyond the obvious? When we allow each other to be in process? The film became a kind of shared language — not to simplify who we are, but to stretch what we think is possible.

Artist, Ella Mahoney

In the first couple minutes of the film, a participant makes an appeal to empathy (“I see what you see”). It’s interesting because I believe that that is the reach that quite a bit of art makes – the gap between what I see and what you see. After making the film, what do you think art can do in the face of injustice, cruelty, and greed?

I believe there’s no way to survive without art. It shapes how we live inside the world, how we metabolize what it does to us. Art heals, it educates, it dignifies, it can be glorious despite the unbearable, it transforms us. It gives us somewhere to place the weight. The film doesn’t offer answers, it offers presence, a shared space where questions can breathe.

I think of that moment you mention — “I see what you see” — not as a claim to sameness, but a reaching across, through, towards. An opening. In MEANWHILE, that reach is what binds everything – between strangers, collaborators, neighbors, generations. Not agreement, but proximity. Not clarity, but care. That’s what art can do: make space for what doesn’t fit anywhere else or what has been systematically erased, sidelined, omitted. Hidden in plain sight. Art keeps watch. Art will make time for what has been refused. Make beauty without asking permission.

And in the meantime — in the meanwhile — art becomes a site of resistance. But also of tenderness. Of imagination. When the systems we live inside are built on extraction, on forgetting, on violence, art says: still, we breathe. Still, we make. Still, we sing and speak and move. Even here. Especially here.

Art doesn’t end injustice, but it refuses to normalize it. It offers a space

to metabolize, to feel, and to grieve

the violence more deeply. It keeps injustice from calcifying

into silence. It’s not decoration. It’s declaration. A refusal

to disappear. A way of holding on — to memory, to vision, to

each other.

In MEANWHILE, the act of making was a way to stay alive inside a brutal moment. Not to escape it, but to be fully awake to it — and still imagine. Still dream. Still build. Still create something big enough. Something tender, spacious, honest enough to carry us. I think of the dancers in rehearsal, the breathwork, the slowness of Jacqueline’s line landing, “Even in the fire, we can’t extricate ourselves… the blood that moves through our veins sings the same song…” That’s what art can do. It doesn’t look away. It sings in the fire.

I believe art is a space where grief doesn’t collapse

us. Where beauty isn’t naive. Where the imagined is as real

as the inherited. Where we can

say — we are still here. And we are still dreaming.

Rachel Dalamangas

New York, New York

May 2025

Image credits: Abramorama

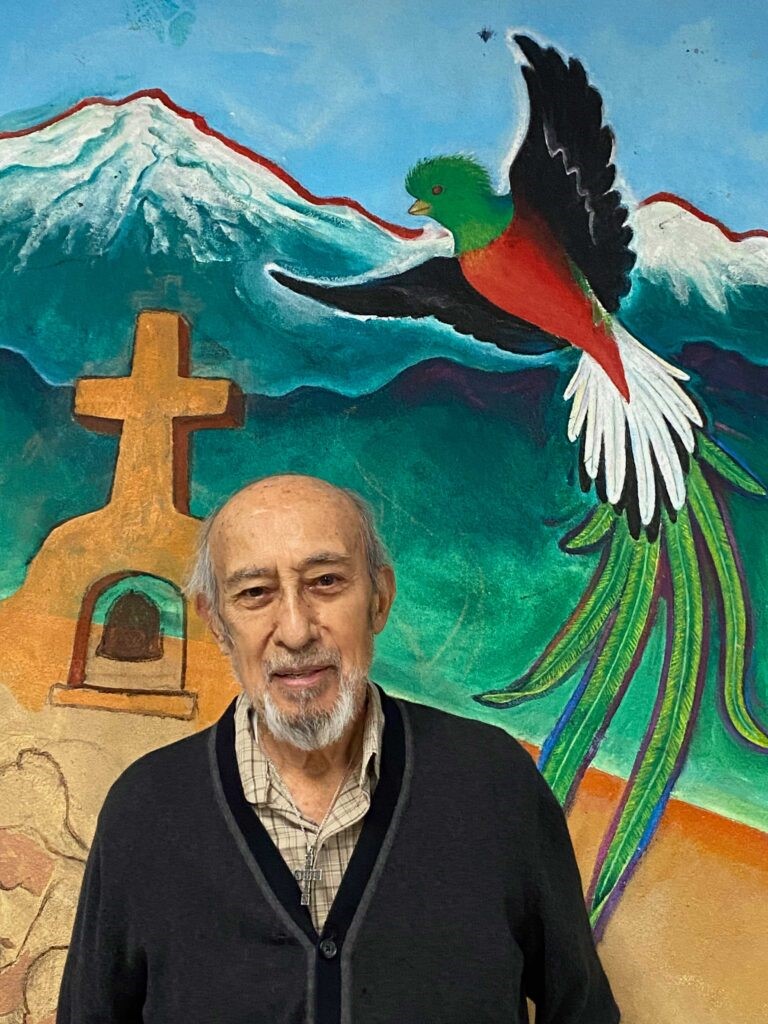

Although his work hasn’t thus appeared in a print edition of zing, Leo Tanguma has twice appeared in interviews for this blog – first in 2012 when I profiled him and years later when he was interviewed by scholars Ben Gillespie and Josh T Franco from the Smithsonian’s Archives of American Art.

Originally from Texas – and claiming that his first mural was a chalk drawing of the town’s corrupt sheriff who terrorized the Chicano community – Tanguma’s presence for over 40 years in Denver and contributions to contemporary art and public arts projects have been meaningful to establishing Chicano art and muralism as integral to American history and modern culture.

His murals, in the same legacy as Siqueiros, are often political, telling stories of overcoming oppression, violence, and greed. His public profile was raised later when two major works on permanent view at DIA: In Peace and Harmony with Nature and The Children of the World Dream of Peace caught the attention of online conspiracy theorists who were determined to prove DIA had an apocalypse bunker for the wealthy and powerful. (My own late father was the superintendent of labor for the West Terminal and said there’s a tornado shelter, but no luxury bunker).

When I took a bus out to the foothills and visited Tanguma for that first interview in 2012, I was struck by how sincere and eager he was to do good with art – that he fiercely believed it was art’s job to address hardship.

For Cinco de Mayo (especially if you’re in Denver), read about Tanguma in zing here and here.

-Rachel Dalamangas