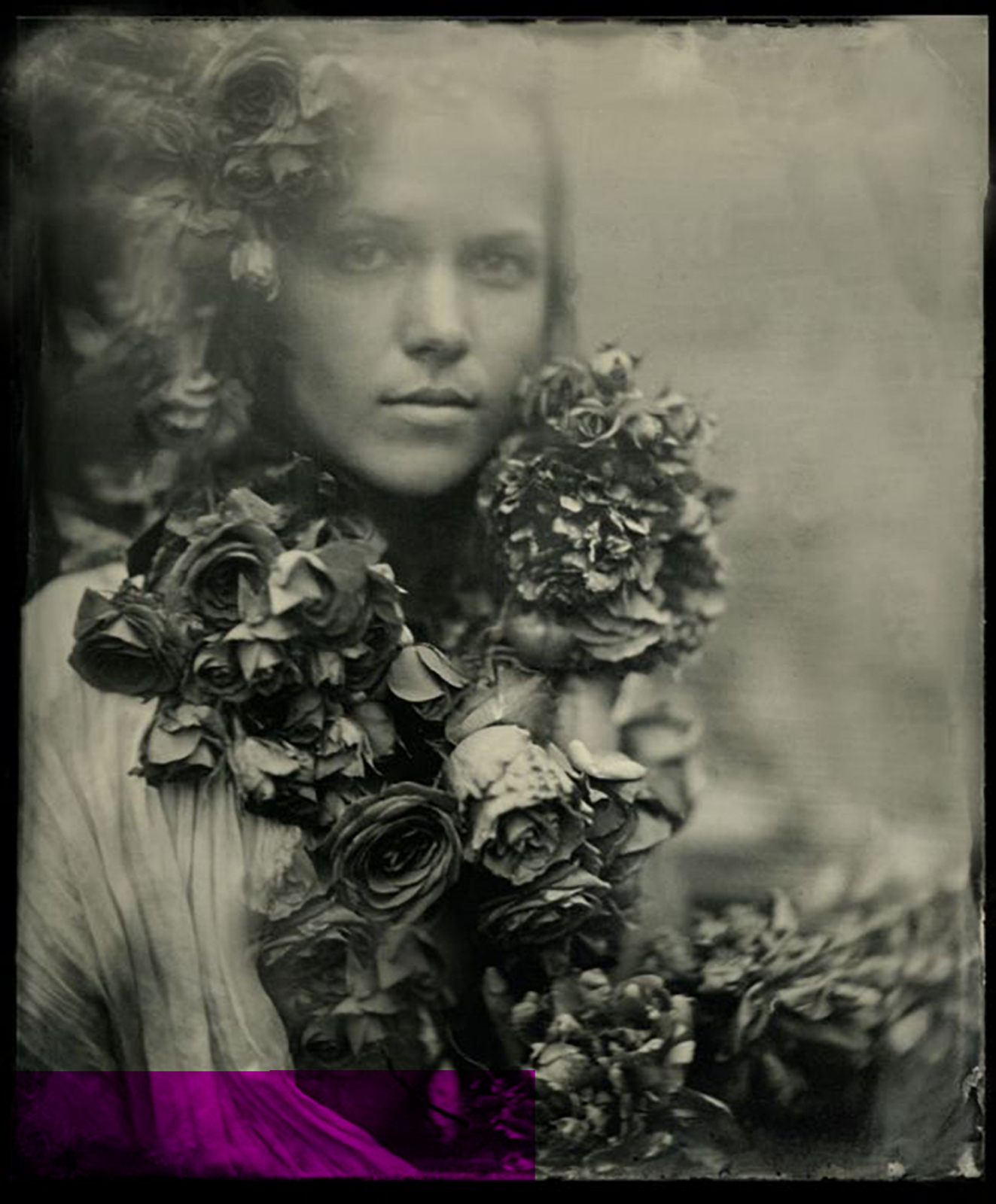

Portrait by Mark Sink, 2012.

With a portfolio that dates back to the late 1970s and an omnipresent energy, Mark Sink has made himself a steadfast pillar in the Rocky Mountain art community. He started his career in commercial photography in New York, canoodling with the likes of Andy Warhol and the rest of The Factory crew, and now lives and works as a fine art photographer and curator in his hometown of Denver, Colorado. Mark is fully dedicated to the medium, and prefers the traditional collodion process and aesthetic to the modern convenience of digital technology. His images, typically portraits and nudes ornamented by flowers, leaves, and water, are ethereal and haunting, and harken back to the work created by his great-grandfather James L. Breese who was an early twentieth-century photographer in New York. Right now Mark is working harder than ever to make this fair mountain city a known art destination on an international level, and he does so by showing endless support for artists and the venues that show their work. He was one of the original founding members of Denver’s Contemporary Art Museum, and curates dozens of gallery shows each year.

Mark’s most ambitious project to date, though, is the Month of Photography, a biennial citywide celebration of the photographic medium started in 2004, which is in full swing right now. This year he curated twelve exhibitions, all occurring during the months of March and April. Also during MoP is a weekly happening he organizes called The Big Picture, where artists submit their work to be shown in public as wheat paste posters. Of course he was generous enough to spend some time exchanging emails with me as he dashed around to meet deadlines and attend openings during what is undoubtedly his busiest time of year.

Interview by Hayley Richardson

In 2013, during the last Month of Photography, you did an interview with Gary Reed where you expressed that you were thrilled with how much the event has grown but cautious to not let it get so big that it becomes a struggle to manage. You said, “I like it the way it is right now it’s big enough!” In reference to that statement, how do you feel about the way things have taken shape for MoP in 2015?

I like the size it is now. We are at max capacity . . . I do MoP myself, my wife Kristen does the posters and fliers. We don’t have major funders. I like it moneyless. It has great potential and could be a cash cow of funding . . . but money ruins everything . . . it would ruin my MoP.

The show you curated at Redline, Playing with Beauty, is the signature exhibition of MoP and you’ve said it took two years to put together. Working with a broad theme, you must have come across an astonishing array of work. Did you encounter anything that challenged your perspective of beauty? What kinds of trends did you pick up on that might be surprising to others seeing this show, and what kind of work didn’t make the cut?

The title was first “On Beauty.” I changed it to “Playing with Beauty”. . . partly because I really opened Pandora’s box with the subject of beauty. My mission was to present my rather serendipitous encounters with the different interpretations of beauty with the human form and the western landscape.

Not making the cut . . . I was struggling with social documentarians and making them fit . . . I had a few in line like Kirk Crippen’s (love his work) and work from Africa . . . sometimes it was purely budget and or dealing with big Blue Chip Galleries that really look down on loaning work to little ole Denver. Borrowing work from one big east coast dealer was harder then assembling the whole show.

The Big Picture is another stand out event for MoP in Denver, and has spread all across the globe. How do you go about selecting which pieces become part of the The Big Picture? Also, why is The Big Picture a black and white project?

We have a standard submission link . . . the submission fee pays for the printing. I pick the work . . . I am the easiest judge in the world . . . if I don’t like the work submitted I often go to the artists website to pick something . . . often I find great work they didn’t think to submit . . . they go from the barely making it in to a top image . . . I also like picking from the website cause a I have more visual and curatorial control. People send the strangest things then their blogger site has amazing things.

It’s black and white because of the Kinkos plotter machine that makes the prints . . . it was made famous by Sheppard Feiry, JR, and others. Cheap fast easy and the thin paper absorbs the paste well.

The history of photography is quite fascinating because it has a rich variety of processes and styles. Now, with so many cross-disciplinary approaches developing in the art world, the qualities that define a photograph are continuously blurred. Galleries hosting MoP exhibitions are showing work that is sculptural, mixed media, etc. and placing it under the photography umbrella. Can you articulate what you see happening here? Is there a new movement taking shape that has no immediate connection to the photography process but somehow relies on it on some conceptual level?

Anything goes with art photography . . . Lots of searching is happening now.

I like the direction work is going that is true to the medium, not faking another medium.

Digital has remarkable new ways of seeing very low light with highly sensitive chips . . . and projectors are strong and can shoot on mountains and buildings, laser etching..great things are happening . . . why try and look like an old Silver Print or Platinum print . . . I hate that fakey instagram filter thing . . . that has swept the app world. Just awful, it’s a reflection of our fake-ness in society.

I see a movement with the gushy romantics in still life and portraits ..the master painters of light . . . the Vemeer light. People like Hendrik Kerstens, Bill Gekas, Paulette Tavormina.

A giant movement has taken off world wide with reverse technology. Pinhole, alternative processes, and conceptual of shadow and mirror. The early lost art crew is a huge quickly growing community I am close to. I personally am going reverse . . . I am at the 1850s with collodion tintypes and heading further back to camera-less and camera obscura.

Yes, your work has a strong connection to the past, both in the processes you utilize and with your aesthetic, which feels reminiscent of a ghostly, bygone era. You often cite your great-grandfather, photographer James L. Breese, as an influence and you feature his work on your website. You’ve done a lot of research about him. What has that process has been like, putting together the pieces of your family history, and how has it directed the course of your career/practice?

It has been slowly trickling in for several decades. Many times it’s another researcher looking for information on another character in his circle that will fire me up to put more pieces of the Breese puzzle together. All and all it’s very exciting to bring his story into the light. It has led me into researching that period in NYC in depth. History passed him right by . . . then I will get a book like ( Camera Notes by Christian A. Petterson ) the history of Camera Notes and the Camera Club of NY and there on the first page, “The primary inspiration of the Camera Club of NY was James L. Breese.” I find it interesting how much history passes over so many . . . including women.

I use his camera and lenses for some of my work so yes it has a pretty direct play in my work. And I love simple portraits of women. That is 90% of his work as well.

Throughout your career you have maintained a strong connection to the young, emerging artists of Denver and have undoubtedly become a great resource and mentor to some of these people. As an artist who honed his craft in the Mile High City in the 1970s and ’80s, how would you characterize this generation of local artists compared to those of previous decades?

It’s a new world . . . far more instantly connected and yet the community is somewhat a bit disconnected at the same time. Great unique ideas and talent always emerges and flies off on its own wings without much help. I enjoy watching this happen.

What I am most sad about is the new generation of young artists and how they are burdened by terrible debt from school. Crazy crazy amounts. Fanny Mae in co-hoots with the franchised for profit colleges and universities saddled on them . . . debts of 100k or more from a small local state school? Please. I have become very down on the higher education system for artists . . . it’s growing anger and sadness from many directions. I know many amazing educators but the system is driving a direction of under paid teaching staff, that then draws in really low level frustrated and angry educators, generally art world drop outs. I have personally visited many art classes in our regional colleges and left appalled and depressed. It’s a bad scene that nobody seems to notice or care about.

I agree. The higher education system is like a train running off the tracks when it comes to keeping costs manageable for students. I’ve reviewed artist submissions for galleries in the past, and directors often want to know what schools they graduated from before even looking at their work, so it can be very challenging for hardworking artists who can’t afford a degree to even get noticed. Do you have any advice for young artists struggling with this conundrum? What are some viable alternatives for an artist without a degree to be taken seriously?

I don’t have a degree so I am an example that it is possible to make it in the world without degrees. I wish I had an easy answer. If I had a magic wand I would trim a few nukes and put the billions into supporting art schools and students. History always looks back at the greatness of a culture by the art it produces.

Outside of the visual arts, what inspires you or has an impact on your work?

Walking my dog. Community gardens, getting to know your community through gardening, teaching kids . . . walking in nature.

You are a man who wears many hats: artist, curator, educator, community organizer…When you meet someone for the first time, and they ask “What do you do?” how do you typically respond?

Artist in general . . . During MoP curator . . . Asking a new muse to sit for me . . . a fine art photographer.

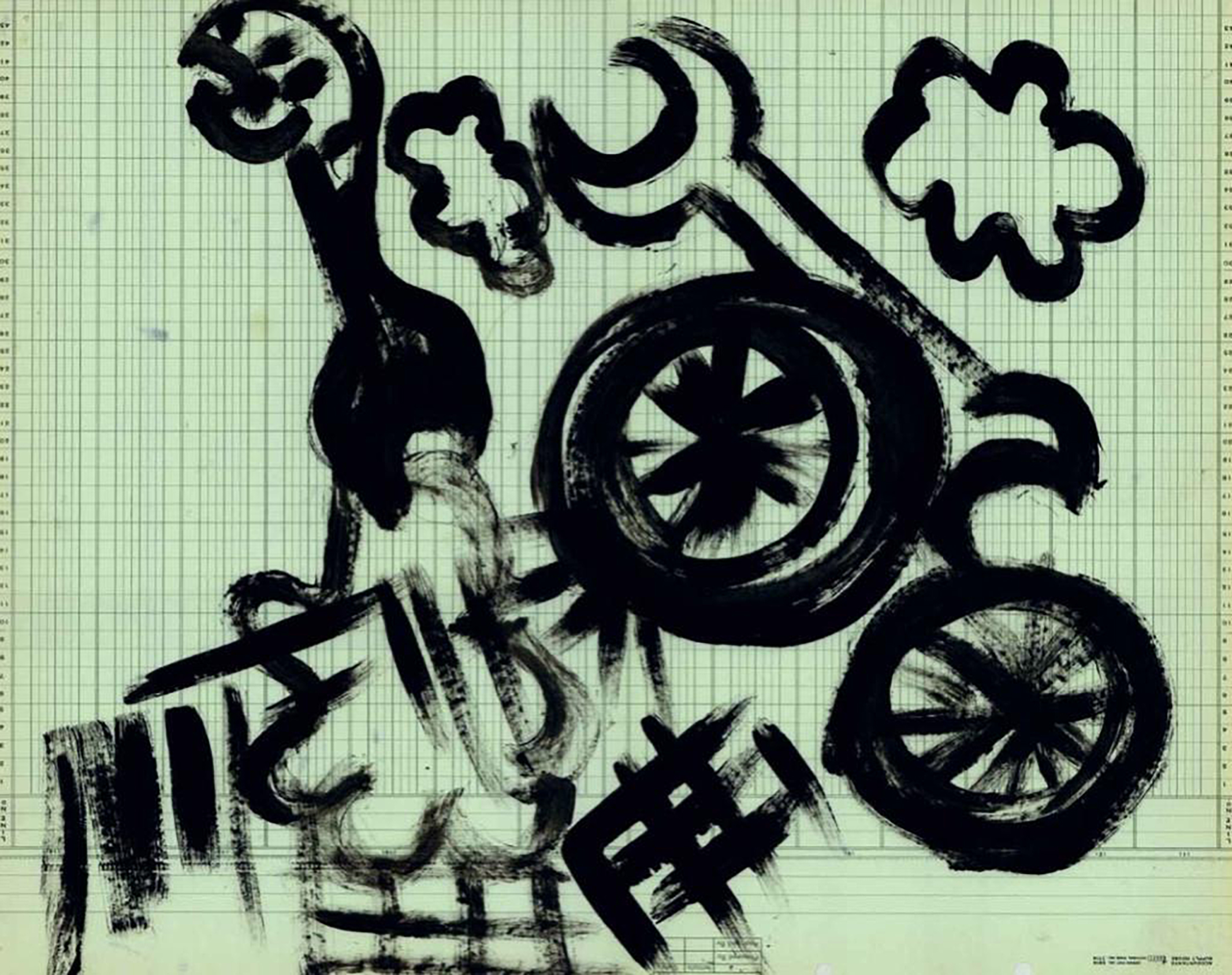

Illustration from Passenger Landscapes: Planes, Trains & Automobiles by Agathe Snow in zingmagazine #23

Agathe Snow’s artwork is driven by action, participation, and creating an experience. She has been synonymous with the downtown New York art scene for over a decade, but has been living in the country for the past five years. At one time it was difficult for her to be removed from the city, which is an integral component to her creative practice. She has since acclimated to her new surroundings and is inspired by the change in scenery. It has been nearly a year since Agathe participated in an exhibition, but she is currently preparing for a show that will reveal some gems that she has kept locked away for the past decade.

Interview by Hayley Richardson

You’ve often described New York City as serving as an extension of yourself. A few years ago you moved away from downtown to Mattituck on Long Island’s North Fork and have been raising your first child. Can you bring us up to speed on what life is like for you now?

[Laughs] It’s different, it’s very different. But I am still really close to New York City; it’s about an hour and twenty minutes so I come in and out all the time. I need my fix, obviously. It took me a while, though. My son is going to be five this summer. So the first year was really crazy and busy with shows and stuff. After about six months I would come home and feel so bad that I was not there taking care of him, so that’s when I started to get settled and got really serious about my artwork and where I was going, but still freaking out about not being in the city, not seeing people . . . so two years into it I’m freaking out. But now it’s been about a year that I feel really good about where I am, much stronger, things matter more. I’ve learned so much, I‘ve practiced, I have much more space to work out here. The people who owned this place before were car collectors, so I have this huge studio space, tools, new materials, new space, new thoughts . . . The world matters. It’s a new me, new world! I felt so guilty never ever thinking about the future, somehow. Everything was day-to-day in New York, so all that’s changed. So I live in the countryside, I have like four acres of land. I don’t see many people, but it’s good. It’s a good thing for me.

Have you exhibited since The Weird Show at CANADA Gallery last year?

That’s the last one I had. But basically, I’ve been working on this big show that’s opening at the Guggenheim this summer, where it’s works from the last ten years of my career and then there will be a screening of my 24-hour dance marathon [which took place] at Ground Zero. I always said I would put the footage of that away and do something with it in ten years because it was too fresh, too much video, too much everything, too many feelings. So I put it away in a safe. And now it’s ten years and the Guggenheim said they would love to premier the video. They asked if I be willing to show it as part of a big survey show where I would get my own space and show work from the last ten years and then premier the video. So that’s what I’ve been working on, basically, this whole year and now it’s almost ready. I have to work on a book about it that’s basically like a 24-hour movie that follows exactly the 24-hour dance marathon. It was shot with nine cameras in 2005 and so the movie screen is divided into seven blocks and you follow the action from seven different angles at all times for 24 hours. And that’s premiering this summer. So, yeah, I’ve been pretty busy with that! I am working on another show about illegal immigration that’s in September. So I got two projects so far.

Sounds like a really big year for you.

Yeah, I am so excited! I have so much energy, my kid is big now and goes to school. It’s a different time, and it’s nice to wrap it all up with this show, you know. Ten years, start something new. It’s good. It’s definitely a big year.

The imagery in your zingmagazine project for issue 23 was inspired by the blur of scenery one sees out the window of a moving vehicle, and in your curatorial statement you reveal that you had just gotten your first driver’s license at that time. Some of the images are scenic, with mountains, clouds and trees, while others appear more urban with bicycles and buildings. What areas/locations were you driving in at the time?

I think it was Colorado, actually. Yeah. We have family in Telluride so we go there a bit.

Do you enjoy driving, or do you prefer to be a passenger?

Yeah, a lot! I love it, I really do. It’s amazing, and I do it a lot to get to the city. I get a lot of thinking done. My road from here to the city is straight line going east and west. It’s so powerful, but it was so scary at first. I failed my diver’s test four times. Eventually I went to the city and passed it really easily, but out here they’re making it hard, you know, because people drive all the time everywhere. It was a real nerve wracking experience, but I love it now. I love it, it’s great. It gives me power and flexibility.

Your artwork is usually very colorful, so it is interesting that you worked with a monochromatic palette in this project. The accountant paper is also unique. What motivated you to portray landscapes in this manner?

I usually try do something with the stuff I find around me, so the people who had the house before, the guy was an accountant. So when we arrived to move into the house, they were still burning old files from their clients. He was in his pajamas over this big burning fire, and we told him we would take care of it, I’ll use it and paint all over it. We had to throw out tons of stuff from the house, but I kept the paper, though.

I’ve always been so afraid of painting, so I had to start really slowly. I used black, black is enough for now [laughs]. I was just working with basic lines and black. I was actually using the same exact lines for the backdrop on this wall piece I’ve been doing, but with a little bit more color in the lines. It’s just enamel paint, it’s just so easy to play with. I would love to learn how to paint one day, but I’m not there yet.

Well that ties in to my next question. Is there any media that you don’t have experience with that you would be interested in trying?

Definitely painting, but I’m terrified of it. I feel like I need to just throw myself in puddles of paint and just move about. I’m completely terrified of it, but it’s so beautiful.

Can you remember one of the first things you created that you or someone else identified as a “work of art”?

It was like a little mobile thing on a clothes hanger, and I just made this cut-out thing with fake fruits. It was really fun, I love doing those, just make things that were completely useless. Then someone at the time at Reena Spaulings was like, “No don’t throw it out. We can do something with this.” So that was my first “official” artwork.

I heard that you studied history in college. Is this correct? What historical periods or events interest you most?

When I was in college I studied northeastern European and Russian history because growing up in western Europe it was just the most fascinating place to me, especially with the spies. My mom and her friend, they went to Russia in 1984 I think, or ’82 or something, and I was so sure they were getting messages to bring back. And then my grandparents, they went on a tour and their tour guide had given them this little ceramic bunny rabbit. And then years later I found this paper inside of it. I pulled it out and there was nothing on it. No messages. But I have always been, like, completely obsessed with it, the mystery, you know. So that’s what I studied. I like it all. The 20th century, though, is just amazing. You can just dig and dig and dig. I went to McGill University in Canada, and I had really good professors and research. I learned how to study it, write about it, approach it. It was fascinating. I loved it, but you can’t do much with [laughs]. It really teaches you to ask questions rather than give answers. You have to constantly ask questions, and as an artist I feel it’s a good way to approach what you’re doing. You’re not really trying to teach anything, just question it.

Do you see your work as relating to any current movement or direction in visual art or culture?

I don’t know . . . I don’t think there’s been enough time or enough space. I did have a group of friends in the ‘90s and the 2000s and we’re all together and stuff, so obviously things bounce off each other and elements pop in and out of each others’ works, but I don’t know if it was really a movement. But at this point I feel pretty far away from anything that would be considered a decision as being part of a group.

Laurel Consuelo Broughton is the Creative Director of WELCOMEPROJECTS, a design practice that engages with everyday objects in a variety of scales and purpose. From architectural developments to couture accessories (created under WELCOMECOMPANIONS), she seeks out the underlying story that makes the ordinary come to life. She is also currently a lecturer at the University of Southern California’s School of Architecture. Laurel’s curated project in zingmagazine issue 23, THE VILLAGE, demonstrates how she sees beyond the normal functions and size of items we use on a daily basis and gives them a new narrative for us to explore. Prior to her work in architecture and design, Laurel worked as managing editor of zingmagazine.

Interview by Hayley Richardson

In the WELCOMEPROJECTS statement for zingmagazine issue 23, THE VILLAGE is described as “the place all WELCOMECOMPANIONS call home.” This home comes to life in the Retrospective City, “where common objects have been transformed into functional building types as suggested by their forms.” This work, in both its 2-dimensional and 3-dimensional forms, possesses a Duchampian spirit, especially with the chessboard layout and lobster telephone. How and why did the surrealist lens become so important in you?

What’s interesting about Surrealism to me is that in a number of different media it sought to create a jolt or distance from familiar things so that we could see those same things in a new way. In my work I’m interested in the same end particularly through playing with the shapes of familiar objects but creating alternate functions for them. The shapes then reappear at different scales sometimes building-sized, sometimes object-sized, and sometimes somewhere in between.

The illustrations for THEVILLAGE are like architectural blueprints. Do you create these types of preliminary designs for all your WELCOMECOMPANIONS items or WELCOMEPROJECTS? What’s your creative process like?

In The Village I was interested in thinking about how the shapes of certain everyday objects could if enlarged be similar in proportion to building types we are very familiar with—such as the high-rise apartment building, the office complex or corporate headquarters etc. The cordless phone becomes the high-rise apartment building and the button becomes the office complex or corporate headquarters.

As far as my process goes, drawing definitely plays a role in all sorts of different ways. In The Village the project literally is the drawings. For WELCOMECOMPANIONS drawing might be used in the beginning to explore an idea and then to convey the designs to the manufacturer and then often we use drawings in our promotional materials.

Storytelling is another central element in your work. Are there any particular stories that made a significant impact in your life that may have laid the foundations for how you work and conceptualize now?

I was a voracious reader as a child and I think that definitely had an affect, particularly the magical realism that you find in children’s and young adult books—like The Borrowers or even Madeleine L’Engle or The Phantom Tollbooth. In a certain way it’s that same kind of wonder that I try to instill in my work but though objects and our interactions with them.

Speaking of stories, what is the story behind the name of your company?

The name WELCOME came about because I didn’t want to use my own name and I also didn’t want a studio with a faux research-y sounding name. I wanted something that seemed familiar. The studio is called WELCOMEPROJECTS and so WELCOMECOMPANIONS seemed like a natural offshoot for a line of accessories.

You recently collaborated with director, artist, and writer Miranda July on a collection called “Classics” for WELCOMECOMPANIONS, which “takes the phenomenon of a named bag to its most extreme.” The bag, The Miranda, is simple and unassuming from the outside, but inside there are specialized compartments for eccentric things like a single almond and a tissue-sized security blanket. Who else do you think would be an interesting person to collaborate with on a super-custom namesake bag?

It’s interesting you can learn so much about someone via what they carry around in their handbag. The Miranda really evolved in the design process from being just a namesake bag to being the limited edition art piece that it is now. I’d love to know what Joan Didion or Sophie Calle carry around in their handbags.

What would one find inside a Laurel bag?

I don’t know that there is anything particularly unexpected in my handbag . . . up until recently I carried around a two-dollar bill that I got 15 years ago on a visit to Monticello, Thomas Jefferson’s home in Virginia. The house is full of all these customizations specifically to Jefferson’s day-to-day life- such as his bed existing in a the wall between his study and his bedroom—so that on one side of the bed he got up in his study and the on the other side he got up in the bedroom—this was in case he wanted to get up and just start working immediately.

You have an educational and professional background in architecture and teach at USC’s school of architecture. What new ideas or projects are you and your students currently exploring?

With my students I’m most interested in providing ways of seeing and thinking that pertain to design. Most of my studios are about getting the students think outside of pre-conceived notions or conventions.

Los Angeles has served as your base of operations for many years. What is it about the city that keeps you inspired, or helps facilitate your means of production?

I constantly find Los Angeles inspiring from the oddities of the built environment to the culture of narrative and make believe that originates here. It’s also still a center of production which means you can find nearby almost any material you can think of. It’s hard to imagine trying to make things in a place where every material has to be ordered and shipped in.

What’s on the horizon for WELCOMECOMPANIONS/WELCOMEPROJECTS in 2015?

WELCOMECOMPANIONS has a new collection launching in February called Wrong Side of the Bed, which I’m pretty excited about!

Put a rare book in the hands of author Bradford Morrow and he will tell you about it like a sommelier discussing fine wine and handle it like a newborn kitten. Morrow has devoted his life to literature, working since his 20s in a variety of facets of the industry. After attending grad school at Yale, Morrow ran a rare bookshop in Santa Barbara, California, which he later sold in order to launch the innovative literary journal, Conjunctions.

Morrow’s seventh novel, The Forgers (Mysterious Press/Grove Atlantic, November 2014) draws upon his area of expertise, telling the story of forgers in the rare book trade. Our narrator is Will, a semi-repentant and publicly shamed forger—erudite, perhaps a bit nerdy, and sly as an alley cat. His lover Meghan’s brother, a book collector named Adam Diehl, is discovered half-murdered and missing his hands. When Adam dies, his hands and killer are nowhere to be found. As Will tries to recover his reputation from his unsavory (if esoteric) past in order to build a stable home life with the grieving Meghan, he is stalked by another forger whose abilities rival his own.

Morrow is wily in his ability to tinker with genre. The reader who appreciates finer details is rewarded with a trail of narrative lacunae the size of a pinprick and an exquisite tone that is just barely, barely uneasy. Morrow knows how to lay canvas on a frame and stretch it just until the fabric is so thin, one cannot tell whether one is looking at reality or fabrication. The portrait of Will, as he tries to put his life back in order after being exposed as a highly skilled forger, is moving. Will is both an artist and an addict, and his disgrace saturates the page. The deeper thread that drives Will is the artistic urge to have a hand (ha) in beauty and history, and thus much of the novel can be read as a series of meditations on art itself.

I met with Morrow in his Greenwich Village apartment (stuffed floor to ceiling with books) to discuss The Forgers, the idiosyncratic book trade, and what a little imagination can do to alter history.

Interview by Rachel Cole Dalamangas

How did you get involved in the world of rare books, which inspired The Forgers?

Growing up as I did in a household where there were very few books, I suppose I’ve spent the rest of my life overcompensating by surrounding myself with all kinds of books, from beat-up paperbacks to rare first editions. I’ve done almost everything with a book you can do, from writing them to binding, selling, editing, publishing, translating, collecting, and teaching them. All of these are facets of my lifelong love affair with books.

My first job in a used bookshop had more to do with handling reading copies of classics from every field than with rare books, although I was always intrigued by the volumes the owner kept in a glass-fronted cabinet. They possessed a kind of magic that to this day I can’t quite explain. When I went to graduate school on a fellowship to Yale, I somehow got it in my head that rather than spending my money on typical necessities like groceries, I would acquire first editions of some of the 18th century books I was reading for class. I persuaded myself that reading them in original editions might bring me closer to the text somehow. There was a very dangerous and wonderful bookstore near campus at the time called C. A. Stonehill, and so I bought a mixed edition of Tristram Shandy in the original nine volumes, three of which were signed by Sterne for copyright purposes, as well as a set of Fielding’s Tom Jones in contemporary speckled calf, six volumes. Believe it or not, these were relatively inexpensive at the time, although I did wind up moonlighting in a pretty sketchy Italian restaurant in order to pay off my book debts. After I moved on from Yale, I got a job at a rare bookshop out in California that specialized in modern first editions and that was when I really got interested in rare books. I left the shop after a while and started my own business with some borrowed money. Before I knew it I was in my mid-20s and running a pretty substantial rare book trade of modern first editions in Santa Barbara, California. After putting a lot of effort into that business for four or five years, I sold off most of my inventory and moved to New York so I could start the literary journal Conjunctions.

Have you known any forgers in your dealings?

I hope not!

There is an element of fetishism of rare books suggested in The Forgers. Is that what the rare books community is really like?

No, not always. Scholarship is one of the leading reasons people and certainly institutions collect. Still, every book collector has his or her own reason for participating in what Nicholas Basbanes calls “the gentle madness” of collecting. The collectors I find most intriguing and even endearing are those who accumulate books—books they’ve read and cherished—because it somehow completes an essential part of their life. I have a friend whose rationale for buying signed first editions of his favorite books is to be a little closer to the author—a book that the author actually laid her hand on makes the experience more tactile or vital to him. Those who collect rare books as an investment may be involved in folly because writers go in and out of favor. Back in the early part of the last century, writers like John Galsworthy, for instance, who we rarely talk about anymore, were highly collected. So collecting books is a really tricky investment. But finally, book collecting, like collecting anything, involves a lot of personal imperative, the first and foremost of which is a visceral as well as intellectual love for what is being collected.

Meghan—the narrator’s lover—is the owner of a bookshop. Were characters in The Forgers inspired by personas you know from the book trades?

This is the book I had to research the least because in a way I spent my whole adult life researching it without even knowing it. In retrospect, it seems strange that it never occurred to me before to write about this milieu. So no, none of the characters in the book are drawn from a single individual in the bookselling world, but there are definitely some composites. In Meghan, I wanted to recreate a little bit of my experience with a man I knew when I was going to college in Boulder, Colorado. Dick Schwartz, proprietor of Stage House II, was a real mentor to me. Back then I didn’t have much money, so I would just take books, carefully chosen, and pay him on time when I could. One day he said to me, “Hey Brad, do you know how much money you owe me?” And I said, “Yeah, I do.” He said, “How would you like to work some of it off? Here’s a broom, go upstairs, and do some sweeping and you’ll see there’s shelving and alphabetizing to do up there.” It was as if Dick read an invisible sign hung around my neck, Will Work for Books. I can’t tell you how happy I was to sweep and shelve and pack books for shipment. That said, I tend not to base many characters on specific people. I find it a confining rather than useful approach to character creation.

Landscape is important in your work, and many of your stories take place in bucolic settings, but much of The Forgers takes place in New York City, where you’ve lived for decades.

I’ve lived in downtown New York now since 1981, so I didn’t have to do any particular research on the East Village or Gramercy Park. Every year I attend the New York Antiquarian Book Fair at the Armory, so, again, walking around in my mind through that show with my narrator and a nemesis of his, I didn’t even have to close my eyes to imagine it. I know what it smells like. I know the lighting. I know the dealers there. I didn’t have to give it a lot of thought. It came very naturally.

Bucolic settings are more characteristic of your narratives, and some of how you handle landscape reminds me of Willa Cather’s writing. You’ve written a bit about her, and like Cather, you’re familiar with and affected by both the American Midwest and NYC.

Willa Cather and I share a love of landscape. Landscape to each of us is a kind of character. Nature is interactive and often willful in our books. To me, My Ántonia is as much about the Nebraska prairielands as the pioneers who populate it. My own novels such as The Diviner’s Tale, Ariel’s Crossing, and Trinity Fields are much more landscape-oriented than The Forgers, in part because much of the action occurs in natural environments. In The Forgers, the nature-based scenes in Ireland are invested with a quality of interactivity between people and the natural world. For instance, images of the night sky with its wheeling stars and constellations offer the narrator a kind of magisterial, eternal counterpoint to the transient, nasty machinations of those running around in the darkness terrifying him. Though some of the most violent acts in the novel occur in Ireland, there remains for me a kind of quasi-mythological aspect to the landscape there. Whereas New York scenes and those in Montauk are very tactile and “real” and have a dimensionality, scenes in Ireland verge on nightmare. Ironic, since Ireland is meant to be a safe haven where Meghan and Will are hoping to find peace.

Something that interested me about the parts of The Forgers that take place in New York is the foreboding sense of being watched or followed. I thought about how cameras are now all over lower Manhattan and how the city has been a Petri dish in a way for the privacy wars. Did this mindset impact your portrayal of the city?

I heard recently that you can walk from Battery Park to Harlem and be caught on surveillance video the entire time. It’s my understanding that more and more building owners are compelled to install cameras in foyers, elevators, and front doors for fear of lawsuits if the property isn’t outfitted with surveillance.

The Forgers begins with the line, “They never found his hands,” which is prelude, of course, to a murder. I was thinking, If you wanted to deprive a forger from pursuing his questionable art, what would hurt him the most? Taking away his pens, inks, papers? He could find more of those. No, the answer is his hands. Like a concert pianist, it requires years of practice and great skill to be a master forger. So when accounting for that murder (about which I wouldn’t want to go into details for obvious reasons) I had to think about those nosy cameras, too. There weren’t quite as many of them in New York around the time The Forgers is set as there are now, but the murderer still had to find a way to get around being seen. Comes with the territory, if you want to avoid capture.

The characters in the book who are forging are also sort of classic examples of New York paranoids. But we’re living in a world now in which everyone is paranoid.

The forgers in the book, Henry Slader and Will, and perhaps Adam as well, have all earned their paranoia. They would be crazy not to be paranoid. What’s that line by Delmore Schwartz? “Even paranoiacs have real enemies”? Even though Will’s past has caught up with him, so to say, and he makes an effort to reform, he must look over his shoulder, as the past is a hard thing to shake. A phrase by another author, William Faulkner, comes to mind—“The past is never dead. It’s not even past.” In The Forgers, that concept is very much in play in a host of different ways. For one, the whole notion of forgery involves messing with the integrity of the past, changing the past by creating ideas and objects that are supposedly a part of the past but in fact didn’t exist before. And in a world where the reliability of the so-called objective past is put in question, paranoia about what’s real and what isn’t becomes central to how life and “reality” is viewed. So, yes. Paranoia and the terror of not being in control of one’s fate are very much a part of this narrative. There’s even a section that opens with the line “Dying is a dangerous business,” followed by a brief meditation on how, when you are dead, you lose control of how people perceive who you were and what you did. Death is open season on you, in other words. That’s classic paranoia at full throttle, I think.

You are sometimes labeled a mystery writer, but what especially delights me in the revelation of a mystery in your works is that you are a writer who will reward the detail-oriented reader. For example, you only name your narrator once.

I don’t really think of myself as a mystery writer, as such, and tend not to play by the traditional rules of mystery or crime fiction. I’ve always been considered a literary writer, whatever that means, but have in recent years gotten very interested in working with genre, which I consider a profoundly rich form of literature. Having said that, I do very much adore detail, and it’s just in my nature to bring my narratives to life with as much nuance and meaningful detail as I possibly can.

As for Will, he does not like his name. I was halfway through writing the book before realizing he hadn’t given his name. It didn’t take much deliberation to figure out why he didn’t, but I wanted him to offer it up, if grudgingly, just once. I thought Will was appropriate because he’s willful. Also, there’s a famous 19th-century forger named William Ireland—one of my all-time favorite forgers—who created Shakespeare (another Will) letters to give to his father. Ireland’s father was a Shakespeare scholar and collector, and since there are only a handful of bona fide Shakespeare signatures, young Will Ireland saw an opening to create some ersatz manuscripts to enhance his dad’s collection and thus please his father. He got away with it for quite a while. Some great forgers such as Ireland and Thomas Chatterton are actually collected in their own right.

Will, the narrator, is reliable, but as the novel progresses, the tension that develops is a did-he-or-didn’t-he-do-it thing. Of course, he’s also among other forgers who are just as suspect.

Well, the reliability or unreliability of the narrator is very similar to forging. It all has to do with imagination and making things up. If you’re good at it, you can get away with it. There’s a line in another of my books, “It takes a lot of truth to tell a lie.” If you stop and think about it, for a lie to work, it has to be mostly truth because if it’s just a pure fabrication, nobody’s going to believe that lie. But if you frame the lie in truth, people will be inclined to believe. So when people in this novel are forging, masters that they are, they know it’s imperative that their forgeries are grounded in truth. For example, to properly forge Conan Doyle papers, as we see in the novel, the forger would have to have done extensive biographical research and have an empathic knowledge of how the author’s mind worked. He would have to really know the period, work with materials that are as close as possible to the period. Nibs, ink mixtures, everything has to sing authenticity.

Forgery is also in a way an act of betrayal, and betrayal is also a theme of this book.

I think that when my characters, and especially in Will’s case, are making forgeries, they honestly believe they’re bettering the world. We on the outside may consider this a rather insane thought, but if you can forge an interesting document well enough, add something intriguing to the history of literature, for instance, can make something great out of the ether, then it’s not impossible to delude yourself into thinking this is a good thing. It is, I guess, an elaborate form of self-betrayal to think like that.

But betrayal has a role in almost all novels. Betrayal—in politics, in love, in business, you name it—is one of those things that humans unfortunately do. It’s an activity that sparks a crisis, which in turn can often be central to an interesting narrative. I think in The Forgers, Will in particular has the capacity to believe that he’s not doing it for the money and that he’s just doing it because he needs to. Much as I am fond of him, I’m fully aware he’s a deceiver. He’s also a writer who creates narratives that didn’t exist before. He loves going back in time and mucking with it. He adores laying claim to literary history, to biography, and bending it to his will. And if you can bend history perfectly enough, the original historical fact becomes wrinkled, complicated.

I’ve always been interested in memory and how memory is a function of an original perception that has been shaded by desire—the desire to reshape the moment that was just lived into something more palatable and fulfilling. I don’t want to play his analyst, but I do think a lot of the forgeries Will makes are, in a way, in (admittedly twisted) honor of his mother because she was a great calligrapher, his teacher and inspiration.

Will says at one point, “History is subjective. History is alterable. History is finally little more than modeling clay in a very warm room.” We know that Will’s character is morally shaky, but I found this train of thought about history insightful.

The Western world’s very first historian, Herodotus, is called The Father of Lies. Why? Because he was really a writer of historical fictions as much as anything. Where he couldn’t verify, or if he needed to fill in lacunae in an account of some war, say, in North Africa, he simply made things up and approximated. Objective, verifiable fact is, in the everyday world, as rare as hen’s teeth (maybe rarer, since there might be a genetically altered hen out there somewhere with incisors and molars, who knows?). Once people armed with imagination and predisposition witness anything, it morphs. I’m not saying we’re all delusional, by the way, but we are to some degree creatures of approximation, certainly when it comes to emotions. So yeah, to be sure, one of the themes of this book is to look at the idea of what is real and what is illusion, what is authentic and what is a fabrication meant to trick the eye into believing it is authentic.

Which implies something intrepid about art. The Forgers is asking, in a way, what is the role of imagination in the world?

Imagination is what we use to get through the day. It funds and nourishes us. Even when we’re asleep, imagination is firing up our dreams. Imagination is the prime mover of any individual’s life. You can imagine that there is a god you will worship that is your main reason for living and breathing. You can imagine that there is no god and you’re not going to have anything to do with such a crazy idea, and you’re going to imagine a way to be ethical without having to follow an ancient rulebook. And what I find fascinating is that you can imagine yourself as being very, very innocent and a very good person, and you’re not. There are a multitude of things that shape an individual life, but imagination has to be at that top of that chain.

Protagonists in your books tend to behave badly in order to protect something beautiful or special or good. Will, for example, rationalizes making forgeries in a variety of ways, one of which is convincing himself that he does it in order to create a good life with Meghan—and their life together is indeed kind of lovely. I thought in a weird way that might be what art does—keeps things that are beautiful and precious and strange, and protects them for us, but sometimes at a price.

And enlivens them, because most artists I know, not just writers, work in order to share with others, the ultimate purpose being to offer a gift to someone else, probably someone you won’t ever meet, so they can share in your experience, dreams, ideas, vision, life. I’m not the kind of writer who is particularly interested in drawing the reader into embracing any philosophy or worldview but I do like the simple idea of building something as best I can, and sharing it with those who might want to commune.

If you’re a fiction writer, you’re making things up, but it’s also important to be absolutely truthful, as honest as you can be, sentence by sentence, and every word has to be the truthful word. You have to create a mathematics of truth that constitutes a book and it has to answer to itself or else it’s not going to add up. I don’t like fiction that smells like fiction. There’s a certain stench. I love fiction that makes me feel I’m truly experiencing a fact. Obviously, I’m not wedded to only realist fiction or historical fiction. I love Naked Lunch by William Burroughs, but that book is just golden in terms of the truth page by page.

Does this relate to your more recent tendency to write in the mystery genre?

When you think about it, everything is steeped in mystery. Many novels are crime novels in the sense that they explore the human capacity for subversive behavior, harmful behavior that goes full-bore against the grain of societal mores. A lot of fiction investigates subtle criminalities that occur in everyday life. Not necessarily robbing a bank or shooting a bodega clerk, but the moral equivalent of such rotten, even evil behavior, is often at play in the narrative arc of much fiction. Nursery rhymes, fables, and fairy tales often portray some of the most diabolical, violent, and deplorable acts humanity is capable of. London Bridge is forever falling down and don’t try to put Humpty Dumpty back together again, for he’s a lost cause!

As for your own process, it sounds as if you tend to write quickly?

Sometimes I write very slowly. But The Forgers was white heat fast, written in a matter of months. Otto Penzler, my editor, runs Mysterious Press, and he has a wonderful series called Bibliomysteries, for which he asked me to write a short story. That’s when I got that opening line about the hands, and I asked Otto if I could write about forgers. He said, “Absolutely, just so long as there are books and there’s a murder.” Those two elements are the premise. I started with a short story last year in the spring, some pages and notes. It shot way past the 50 pages. When I finally gave it to him, I gave him 86 pages, but I had already moved on past 120 pages. I said, “This isn’t all,” and I showed him the rest, and he asked me if I could get all of it to him by the end of the year. Every day I got up and couldn’t wait to get back into the forger world, so it was done ahead of schedule. When I handed in the novel, I turned around the next day and wrote another bibliomystery called The Nature of My Inheritance, as a way of fulfilling my original promise to Otto. That one came out this past summer.

What are you working on now?

I’ve been working on a book for many years now that I am finally finishing. It’s called The Prague Sonata, and is a novel in which the holograph manuscript of the second movement of an unattributed, magnificent piano sonata from the late eighteenth century surfaces in New York. Its owner, Irena, is a Czech immigrant dying of cancer who passes it into the care of a young musicologist, Meta Taverner, after telling the hair-raising story of how it came to be in her hands. In 1939, when the Nazis came to Prague to establish “the protectorate,” this manuscript, which had been inherited by a woman named Otylie after World War I, was deliberately broken up in three parts to save it from Reich confiscation. Oytlie gave one movement to her husband, who perished into the underground, another to her best friend Irena, and she kept one part for herself. In short, Meta’s quest to locate the missing movements of the sonata takes her to Prague, London, and elsewhere. It’s a novel that has involved doing research in places as far apart geographically and culturally as the Czech Republic and the hinterlands of Nebraska, not to mention endless reading and consultation with experts about Beethoven and other composers from Mozart and Haydn forward. I hope to have it completed by year’s end.

Cover art by Gary Taxali; Blab World #2

Monte Beauchamp is the award-winning, Chicago-based founder, editor, art director, and designer of BLAB! magazine, a comics anthology first published in 1986 as a self-published fanzine, with book projects including The Life & Times of R. Crumb (St Martin’s Press), Striking Images: Vintage Matchbook Cover Art (Chronicle Books), The Devil in Design (Fantagraphics), among others. BLAB!, in its current form of Blab World, is now a highly-regarded venue for contemporary artists working in sequential and comic art, graphic design, illustration, painting, and printmaking—a love song to these underground worlds often placed on the periphery of the visual arts. Monte teamed up with photographer Paul Elledge to produce BLAB! magazine: Inside Out, a project in zingmagazine #21 in which the artwork within BLAB! finds its way out into the cold, cruel streets of Chicago. I met Monte for the first time in 2010 at the opening of the outstanding BLAB! exhibition he organized at the prestigious Society of Illustrators in New York. I’m now fortunate to once again get to opportunity to speak to Monte about BLAB!, his project in zingmagazine, the world of print, and his newest book, Masterful Marks: Cartoonists Who Changed the World, published by Simon & Schuster, which features top illustrators telling the stories of sixteen monumental figures in the world of comic art and pop culture, including Walt Disney, Dr. Seuss, Charles Schulz, The creators of Superman, R. Crumb, Jack Kirby, Winsor McCay, Herge, Osamu Tezuka, Harvey Kurtzman, Al Hirschfeld, Edward Gorey, Chas Addams, Rodolphe Topffer, Lynd Ward, and Hugh Hefner.

Interview by Brandon Johnson

What did you set out to achieve in founding BLAB! magazine?

There were no grand plans whatsoever. How BLAB! came about was a total fluke. One evening after work back in the mid-’80s, I began bellyaching about shenanigans taking place at work where I was employed as an art director. To help take my mind off it, my wife at the time suggested I draw a comic book, which I didn’t have the desire to do, but several days later the idea of creating a fanzine about comics flashed in my head.

I had always felt that if it weren’t for MAD magazine, the sixties counterculture may never have happened. MAD ingrained in its readers the ruse of advertising and the distrust of corporate authority. MAD‘s publisher, William M. Gaines, also issued a very fascinating line of comic books known as E.C.’s, featuring incredible page-turners such as Tales from the Crypt, Weird Science, and Two-Fisted Tales, which were discontinued during the great comic book witch hunt of the mid-1950s.

So I decided to contact the counterculture cartoonists themselves to see if they’d write essays about what influence, if any, MAD and the rest of the EC line had on their work. And much to my surprise nearly all of them gave the project a thumbs up; they agreed to blab about it—which in turn gave way to the title BLAB!

So I self-published a one-shot limited edition of 1500 hand-numbered copies which I schlepped around to independent record, book, and comic book stores and placed on consignment. I also placed a few ads in several comic book publications.

Not long after, I went to the post office box on a Saturday morning and it was jam packed with orders; it was like this for a good solid month and then came a lull in orders—and then four to six weeks later, the post office box again became jam packed with letters, this time with letters from fans raving about BLAB! and inquiring when the next issue would be out, which in turn inspired me to attempt a second issue.

The same week that BLAB! #2 was printed happened to coincide with Chicago’s big summer comic book convention, so I brought a handful of copies to show around hoping to drum up sales. Kitchen Sink Press—which published the work of several of my heroes: R. Crumb of Zap Comix fame; Harvey Kurtzman, the creator of MAD; and Will Eisner, considered by many to be the father of the graphic novel—was exhibiting there so I gave a complimentary copy to its founder Denis Kitchen, who flips through it, and immediately offered me a publishing deal—which blew my mind. Right then and there we sealed the deal with a handshake.

Denis tripled BLAB!‘s press run, expanded its page count, and we also reformatted it as a square-bound, digest-sized paperback. I began adding more comic book stories by the incredible Joe Coleman, Zap artist Spain Rodriguez, and a talented newcomer—Richard Sala. I also assembled a compendium on the influence R. Crumb had on popular culture (which 10 years later was expanded into a trade paperback published by St. Martin’s Press—The Life and Times of R. Crumb). That same issue also sported a magnificent cover by RAW magazine artist—Charles Burns. Partnering with Kitchen Sink Press put BLAB! on the map; from the incredibly brisk sales, I knew we were on to something. Four years later, issue #7 of BLAB! won a Harvey Award (the comics industry’s equivalent of a Grammy) for Best New Anthology of the year.

So that’s how BLAB! got rolling; it was never something I set out to do—it was just a matter of being in the right place at the right time. I had no inkling whatsoever that BLAB! would take on a life of its own and evolve into the full-color, hardback compendium of comics, illustration, found graphics, and articles that it is today.

The Rapture, Ryan Heska; Blab World #1

How does a typical issue of BLAB! come together? Do you always have specific artists in mind for each issue?

Nowadays the process is very nonlinear, intuitive, one that starts with a single inspirational idea and builds from there. For example, I was walking around downtown Chicago one afternoon when a humongous storm hit. Massive gusts of wind were whipping all sorts of objects about and as I ducked for cover, off in the distance I saw a funnel of garbage swirling about in the air being sucked skyward. It was an eerie yet awe-inspiring sight, which set me thinking about The Rapture—and then a scene of people rising skyward interpreted by BLAB! artist Ryan Heshka flashed in my head. So I ran the concept by Ryan who dug the idea, and created a masterpiece. Ryan’s painting was so inspiring I began asking other artists to create “end-of-the world” scenarios that I compiled in a feature titled “Artpocalypse” for the first issue of BLAB!‘s sister publication BLAB WORLD, which in turn set the tone for the comic strips and feature that appeared in that of volume.

You curated a project in zingmagazine #21 called “BLAB! magazine: Inside Out” which features various works that appeared in issues of BLAB! in different formats and mediums and photographed these in outdoor environs around Chicago. It’s sort of a magazine within a magazine—a peek into the world of BLAB! What inspired you to present BLAB! in this way?

Actually zingmagazine did. One aspect of zingmagazine that I always admired was it’s offbeat curatorial nature, which inspired photographer Paul Elledge and myself to present BLAB! in a similar fashion. Rather than shoot the artwork in a hoity-toity setting—such as a gallery—we took a less precious approach and photographed the artwork itself sticking out of garbage dumpsters, in alleys, and on the streets of Chicago.

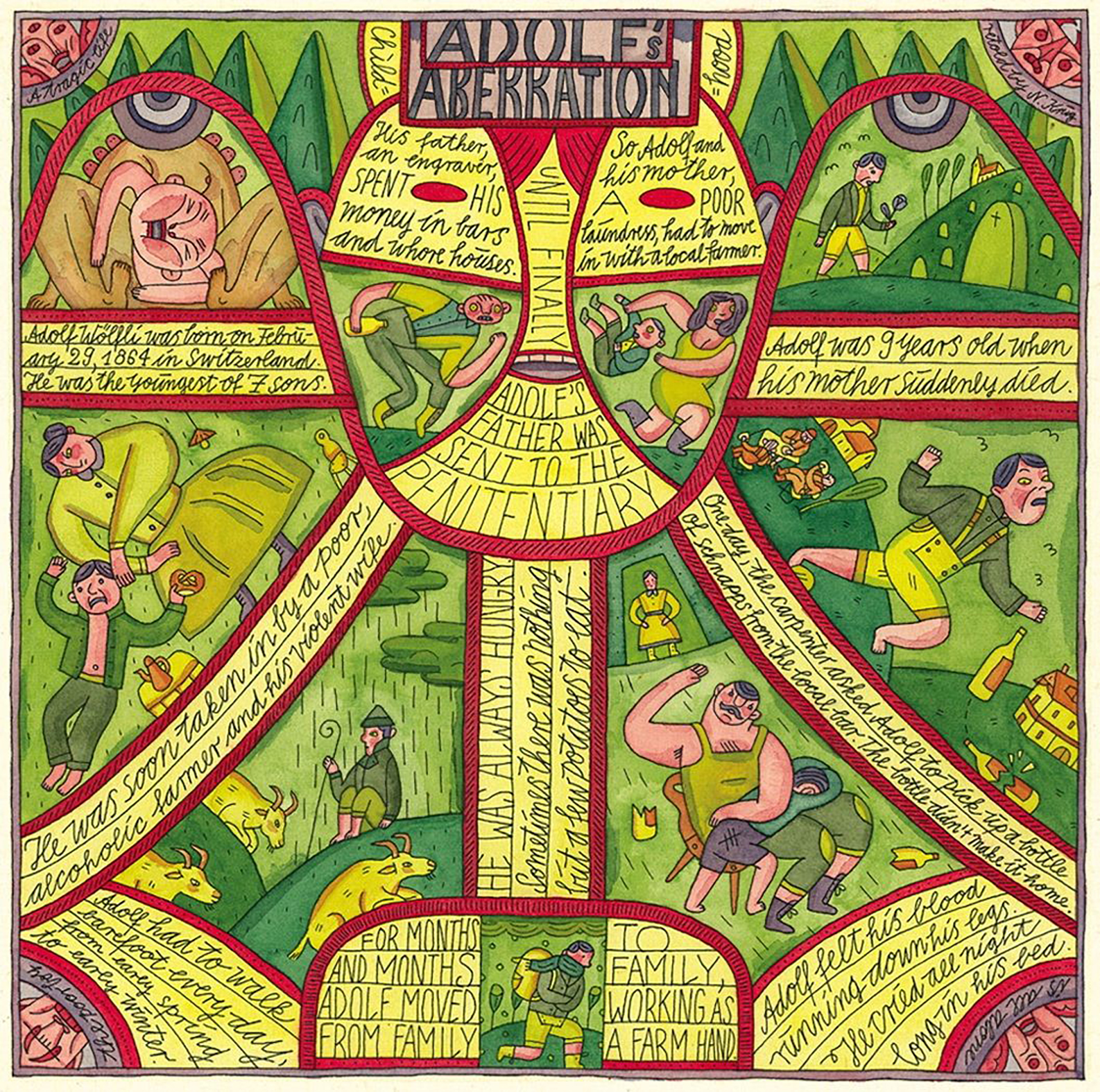

Adolf’s Aberration; four-page story by Nora Krug; Blab World #2

Adolf’s Aberration; four-page story by Nora Krug; Blab World #2

Your new book Masterful Marks: Cartoonists Who Changed the World is a collection of biographies of 16 legendary cartoonists presented through an equally graphic medium as created by other illustrators. There’s a double curation here—first the subjects, and then their corresponding artists. How did you conceive of this idea, and how did you select each group?

In late 2007, I was fishing around for an idea for a graphic novel to produce and the media blitz surrounding the release of the final Harry Potter novel earlier that year set me thinking about the far-reaching effects fictional characters can have on the world. I began thinking of popular literature equivalents from generations before. Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein came to mind as did Sir Arthur Conan Doyle’s Sherlock Holmes, followed by Edgar Rice Burroughs’ Tarzan—whose successful spin-off as a newspaper comic strip set me thinking about cartoon characters of equal iconic stature. Disney’s Mickey Mouse flashed in my head, followed by Dr. Seuss’ Cat in the Hat, followed by Siegel and Shuster’s Superman—the archetype for all superheroes. And then it dawned on me—had it not been for iconic comic characters such as these, the entire cartoon industry as we know it today wouldn’t exist. So I pitched my New York City agent on a collection of short-story biographies told in the very medium the industry itself had spawned—the comic strip—about the monumental creators who pioneered the entire cartoon medium—from syndicated newspaper comic strips to comic books, manga, graphic novels, caricatures, gag cartoons, children’s books, and animation. She loved the idea and that’s how Masterful Marks: Cartoonists Who Changed the World came about.

Any particularly difficult editorial decisions in this process?

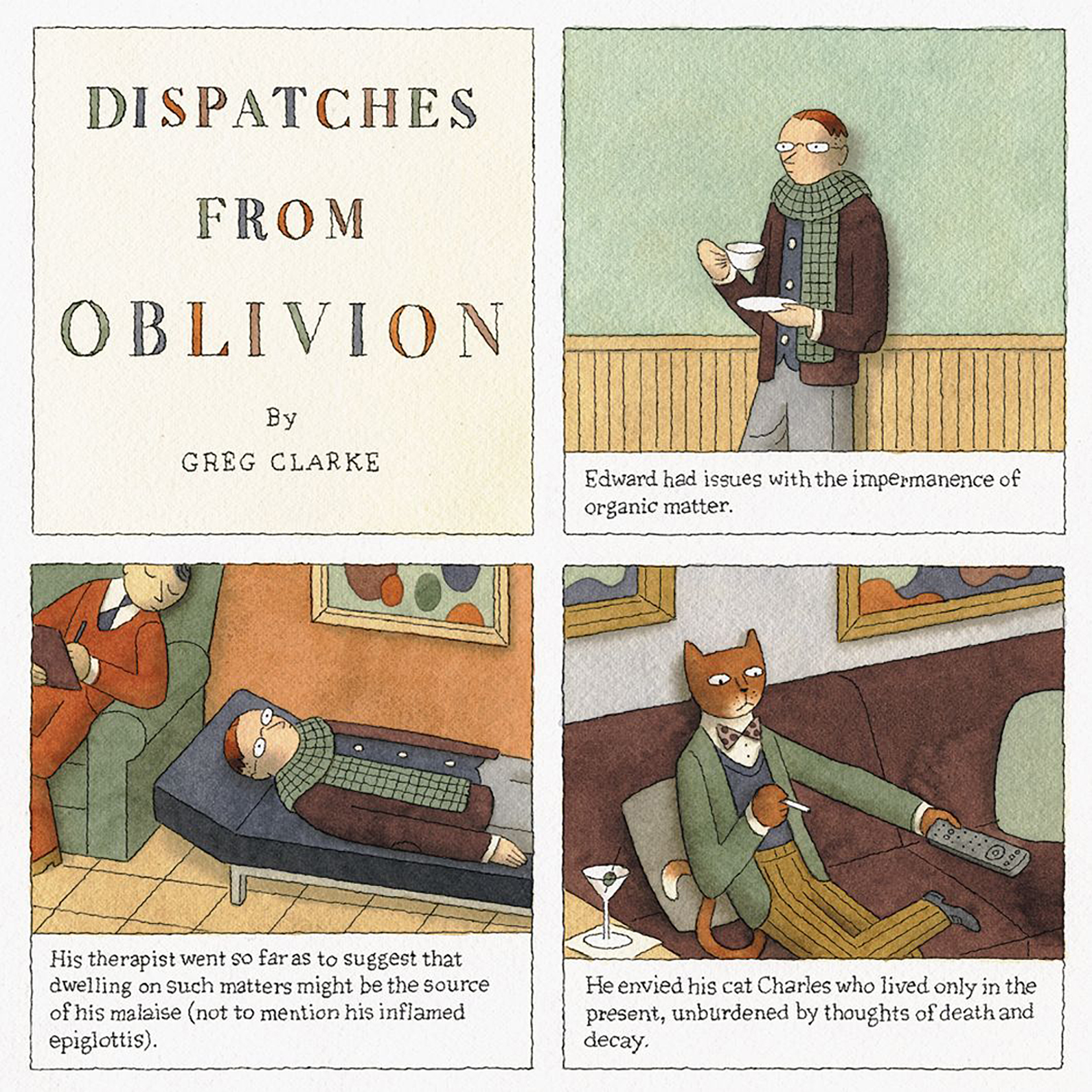

Such a grandiose undertaking is an obstacle course, there are always editorial hurdles to get over, roadblocks to maneuver around. Fortunately my agent sealed a deal with a wonderful, seasoned editor at Simon & Schuster—Anjali Singh. Anjali, what can I say except that she is an incredibly insightful, intuitive, and brilliant senior editor who has a knack for signing fresh and original projects. For example, she brought the graphic novel Persepolis to America, which became a hit and was turned into a feature length film. Anjali turned out to be a dream editor to partner with; we really worked well together and she backed me 100% on the team of illustrators and cartoonists I assembled—fabulous seasoned talents by the likes of Drew Friedman, Peter Kuper, Sergio Ruzzier, Nora Krug, Arnold Roth, Greg Clarke, Nicolas Debon, and so forth. As Masterful Marks was nearing completion disaster struck—Anjali, along with several dozen other Simon & Schuster employees, were laid off. When the news arrived that we wouldn’t be ushering Masterful Marks into the world together, I was devastated. Completely. The very person championing my book was gone and all sorts of turmoil can happen when a book is orphaned. Fortunately, the project landed in the lap of a junior editor who got the project back on track. And then as we were completing the book, what happens? He takes a position with another publisher, and Masterful Marks landed in the lap of yet another junior editor, Brit Hvide, who did an admirable job ushering the book into print. After seven years, Masterful Marks was released this past September and received incredible accolades and reviews from the press. For example, it was included in Entertainment Weekly’s “The Must List,” plugged in USA Today, The Huffington Post, and Library Journal. A most wonderful and totally unexpected perk was receiving a letter from Hugh Hefner (also featured in the book) stating that Masterful Marks was “… a grand compilation.”

Dispatches From Oblivion; four-page story by Greg Clarke; Blab World #2

Dispatches From Oblivion; four-page story by Greg Clarke; Blab World #2

Why do you continue to make print books in this dematerializing world of media?

Well, there’s a caveat to all of this. As long as I’m allowed to edit, design, and package visually content-driven books that I have an intense passion for, that I believe in one-thousand percent, I will continue to create books. It was a long, arduous road to get here. Looking back on the unexpected twists and turns my professional career has taken, I sometimes ponder that had I remained in advertising, I’d have a house all paid off, a hefty savings account, and my dream car—a light green ’56 Chevy with a 3 speed column shift to tool around in. Yet, on the other hand, a rewarding career isn’t always about money, it’s about the love of the game.