Page from “The More I Know About Women” by Lisa Kereszi in zingmagazine 24

Lisa Kereszi’s upbringing in a family whose business was in junkyards and pleasure was in biker rallies seems like an unlikely lead into a world of art and academia at Bard and Yale, but this background is what enabled her to see the world through a cognizant and experienced set of eyes. Likely possessing an acute sense of self-awareness at an early age, Kereszi was able to understand the precarious but also the remarkable aspects of her environment, making her a determined photographer who has the confidence to work alone on projects that would make others feel leery. Her project in zingmagazine issue 24 is a conceptual reflection on this upbringing, utilizing photographs taken by her father during his biker heydays. This project comes directly out of her artist book of a similar name, The More I Learn About Women, published in 2014 by J and L Books. As a new mother, Kereszi is preparing to explore the realms of family life and childhood from a different perspective than she has in the past. Lisa and I exchanged emails, in which she shared the story behind her longstanding connection with zingmagazine, her interest in sideshow culture, and experiences in photography around the world.

Interview by Hayley Richardson

“The More I Know About Women” in issue 24 is your fourth zingmagazine project. While it features cropped images of women’s eyes, it also speaks about your relationship with your father. Your family has had a strong impact on your aesthetic. How has their influence grown with you over the course of your career?

I’m not sure I’d say it has “grown,” exactly, but receded, deepened and changed, as I have gotten further and further away from my formative years. It’s the “You can’t go home again” Thomas Wolfe thing in play. This book was collated and created when I was expecting my child, so that new role I was about to embark on had a lot to do with the impetus and my need for making this piece. There’s a section in the book that depicts children in the rough and tumble biker world I grew up in, dragged to keg parties and hillclimb motorcycle competitions, Bike Week in Daytona, camping out in the Chevy Nomad with it’s Harley stickers on the back, while my parents went out to see Joan Jett (my favorite!) perform at the Harley Rendezvous in Upstate NY. I would never raise a child like that, although I guess it did have positive effects, but it was strange and sort of painful to go through.

You have cited other influences like Nan Goldin, Brassai, and Robert Frank. What other artists, outside of photography, do you connect with or feel inspired by?

Although I just bemoaned my alternative lifestyle childhood, I love John Waters, and his sincere pushing of limits. I’m not a limit-pusher, but I appreciate it and sort of live vicariously when watching characters like Divine, Edith Massey, Mink Stole and David Lochary practice their filthy behaviors. I guess I also love how he pulled this real and true underbelly of poor Baltimore into the art world’s sights, something I can relate to, being born on the wrong side of the tracks outside Philly. Speaking of which, the imagery, mood and character-creating of Bruce Springsteen’s work has always hit me right in the gut. I love David Lynch’s pure weirdness, Louis C.K.’s brutally funny honesty. I grew up on SNL.

Lisa (right) with Erin Bardwell celebrating the release of her book, Fantasies, at the zing office in March 2008

Aside from having multiple projects in zing, you have photographed numerous zingmagazine parties and your “Facing Addiction” series is part of the Dikeou Collection. Could you talk about how you first became acquainted with Devon Dikeou and the zing milieu?

I think I was probably working for Nan Goldin at the time, and she got so many invites to so many cool parties that she would never have time to go to herself, so me being a 21 year old, I took a few of them as invites to go myself! A very early zing party was one of them. I was showing at Pierogi 2000 in Brooklyn, and I think Devon just connected with the work I sent her after I learned about zing at that party. I think it might have been at a bowling alley near Union Square. There were so many fun zingparties that I can’t remember each one well on their own.

Some of the projects featured on your website, like Fun n’ Games and Fantasies, span several years. Are the themes of these projects thought out ahead of time as something you’d like to explore long-term, or do the relationships between certain images taken years apart emerge later on?

I think I come at it both ways. But for the most part, I’ll be interested in one specific thing that is related to a bigger concept, movie theaters or strip clubs, for example, and then I’d go seek out permission to photograph a handful, or a whole bunch, of them. It isn’t until later that they combine with pictures of Coney Island or Times Square or Florida into something bigger, like the series you mentioned, even though my interest in each of them stemmed from the same unconscious (or semi-conscious) place.

Can you recall a time when you felt especially challenged by your subject matter or territory?

I suppose working with family and the failed family business was at the same time both easy and difficult. But you just put your blinders on and press forward. Also, I think finding permission for locations, such as strip clubs, has been particularly challenging, on a practical level. On top of it, sometimes you get the written or verbal permission, and show up to shoot, and the message has either been lost in translation, forgotten, or was never passed down the chain of command to the gatekeeper. It can be frustrating.

Have you ever worked collaboratively with another photographer or other artist?

Not really; I’m a bit of a loner. I don’t even like having assistants!

As a photography professor at Yale you must enjoy sharing your knowledge and experience with students. What has working in the collegiate atmosphere been like for you?

It’s been like getting a second degree all over again, between the re-learning and also the constant flow of interesting people and work going through the building. You have to teach yourself more than you knew before in order to teach the students anything. You need to have something to say, too, a position, a mission, in addition to knowing the technical stuff. It’s also about helping someone find oneself than really recounting experiences, although experiential anecdotes can certainly help someone to understand how things work in the real world.

You had an early interest in writing before photography became your main focus, correct? What kind of writing interested you, and is it something you still do at all?

Oh, I guess I thought I’d be a poet, which is sort a ridiculous career path—but so is visual art! I had an English Lit teacher in college tell me that I didn’t have the love of language necessary to be a poet. It stung, but he was right—at the time, at least. I write a little bit now, but no poetry, just statements about work and essays about things I am interested in, photography-wise.

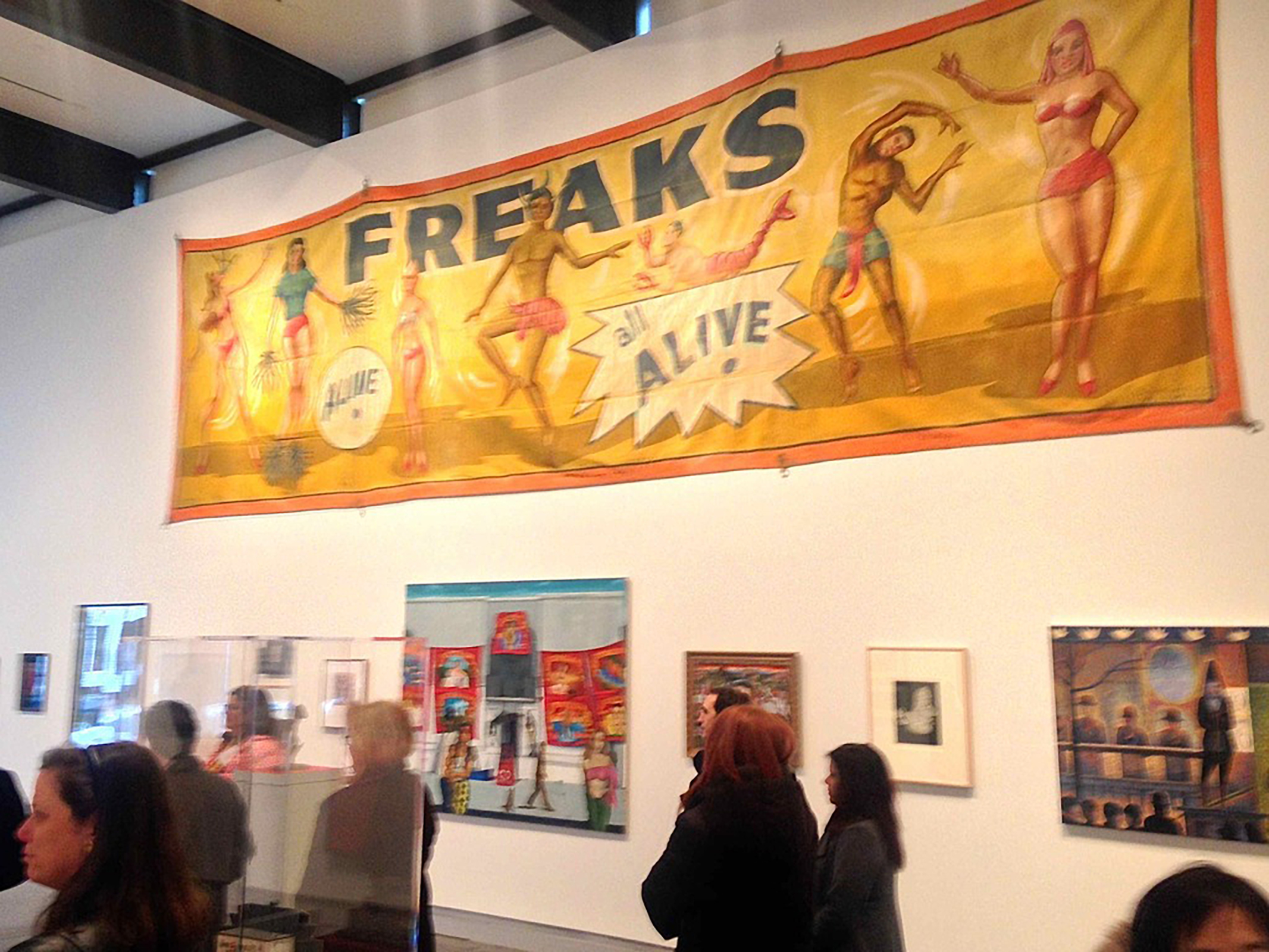

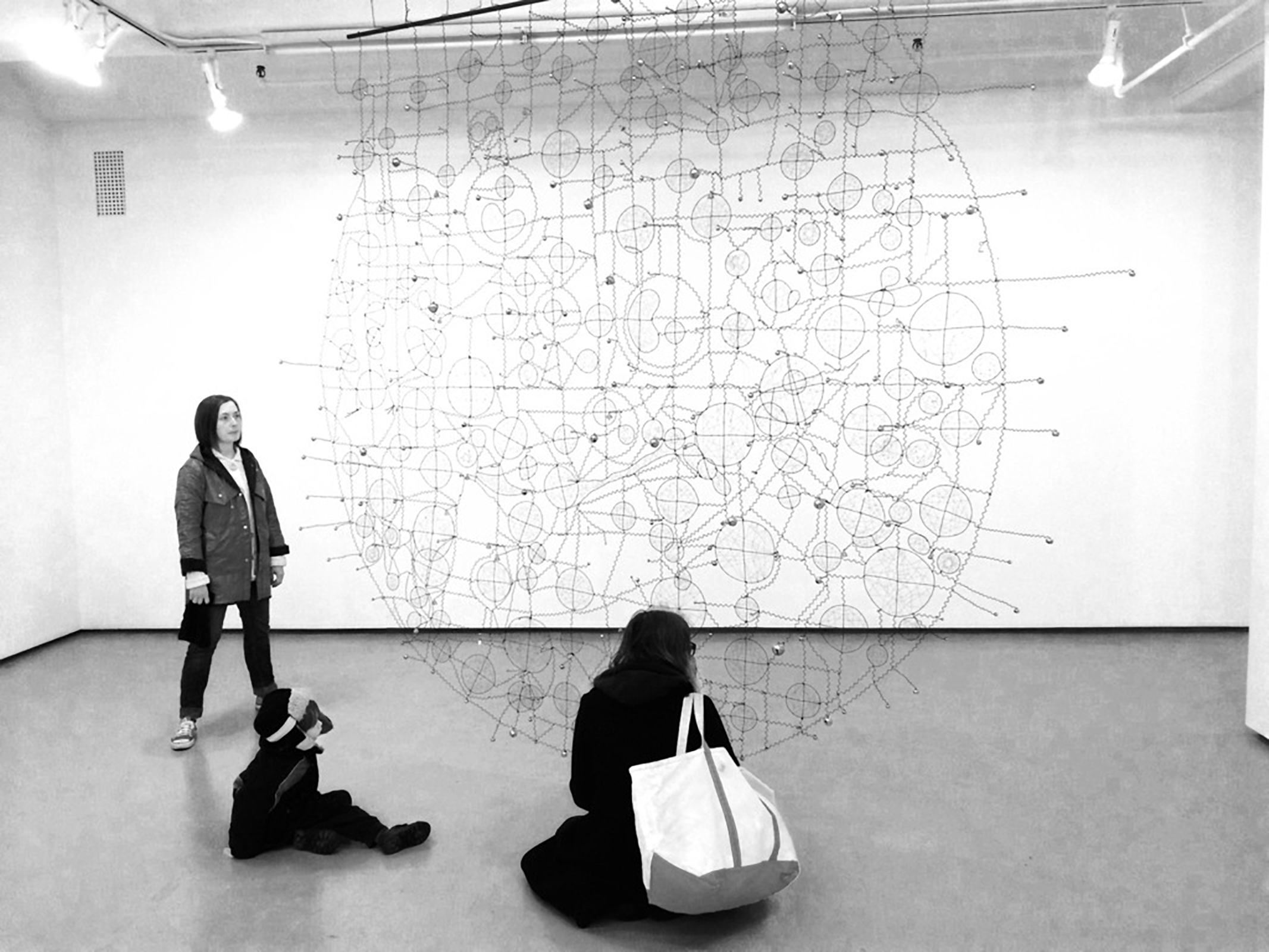

Installation shot of “Sideshow” exhibition curated by Lisa Kereszi at 32 Edgewood Gallery. Image courtesy of Yale Alumni Magazine.

You curated an exhibition, “Sideshow,” at Yale School of Art’s 32 Edgewood Avenue Gallery earlier this year. What was it like organizing this show? Did you learn anything new about sideshow history?

It was a great experience, a lot of work, and a long time in the making. I was inspired by the traveling show that curator Robin Jaffee Frank put together at the Wadsworth Atheneum in Hartford, which I unofficially consulted on and in which I have two pieces. “Coney Island: Visions of an American Dreamland 1861-2008” opens at the Brooklyn Museum this November. When it was at its home museum, in order to run a concurrent show, I was given the opportunity to use the freestanding contemporary gallery at the School of Art by our Dean, the artist and curator, Robert Storr, who is as interested in the low-brow richness of sideshow and carnival culture as I am. If anything, I only wish my “really big show” (over 70 works, and a massive list of programming that included people like Ricky Jay coming to speak) was a REALLY BIG SHOW, but Storr reminded me that this was not a museum show, but one at a one-room alternative space with a limited budget. I had tried showing him a salon-style hang with over 150 works borrowed from far and wide, and I quickly realized as we installed it in January 2015 that he was right—it needed to actually be curated.

I knew a fair amount about this world and who the players were before hand, but the depth of the knowledge of these people is really truly frightening (in a good way.) Performer Todd Robbins got a preview of the show being installed when he hand-delivered his Feegee Mermaid sculpture, and schooled me on details and anecdotes about the pieces in the exhibition and the characters depicted, including artworks that I own, but knew not enough about. In the upcoming catalog, I include my curator’s notes, which explain who the people are who are depicted, so that they are fully developed human beings in a viewer’s mind. It includes background information on people like Eddie Carmel, the Jewish Giant of Arbus fame, and Mat Fraser, actor, performance artist and disability activist.

“Visions of an American Dreamland” is currently at the San Diego Museum of Contemporary Art and I am always curious how traveling shows are received by audiences in different parts of the country, especially this one with a regional specificity. Do you have any thoughts on how people might respond to it differently on the west coast vs east coast?

Well, even in Hartford, where it opened, it must have been a bit removed-feeling. That said, I think the show deals with universal and very democratic things—like the human need for escape from reality. But the big moment, in my opinion, is this Fall when it opens at the Brooklyn Museum, just a subway ride away from the real thing. It’s going to be a big show, although it reminds me, in some ways, of the work and little show I did about Governors Island, which was at the Municipal Art Society in 2004, and then shown on the island later in an old commanding officer’s house. I think about that project, because it’s about a contained, specific place, and it’s also an island of New York, for sure, but I think about the throngs who will go to see this show who have personal, historical, deeply-felt experiences from the place. That was one of the interesting things about doing that Public Art Fund project—people who lived on the island saw the show, and had visceral, personal reactions to some of the depictions of place. For me, it was like my own private photographic ghost town, but to them, a few thousand people, it was once their home.

As an artist who has traveled, exhibited, taught, and photographed all over the world, have you noticed any major differences in how people engage with photographers (or art(ists) in general) in different countries?

The world is a very big place, and the more I teach and meet people from all over, the more I realize how small my place really is! Each culture forms a different kind of museum-goer, who has unique background and connections to make with new work. If anything, I am more aware of how people in public react to the presence of a photographer on the street. Some are very trusting, like in Shanghai, and some are quite the opposite, like in Paris. Some places fear photography, like here, but other cultures value it and understand its importance, like in Berlin or London, I think.

What are some areas of interest that you would like to investigate photographically that you have not done yet, or would like to revisit?

I’m not sure I’m ready to do more revisiting than the current zing project does. Not for a while, at least. I have some ideas up my sleeve, the most pressing of which is something to do with being a new mom. It’s already well-mined territory, but I will find something new to say, hopefully. I also have a pile of junk that I have been adding to all the time—sad, little discarded things I just want to make very basic still-lifes of with a 4×5 camera, when I get my act together and set up a little studio in my office.

What do you have coming up in the near future?

See above!

Olav Westphalen performing “Even Steven,” at Index, Stockholm, photo: Santiago Mostyn

Olav Westphalen describes himself as a “provincial artist without a province.” For some this may seem like a challenging position, but he maintains it just fine by having an open mind and a sense of humor. Using cartoons and comedy as his main vehicles for creative expression, he is able to transcend cultural barriers and address serious topics in thoughtful ways that will make you laugh. Inspiration is found within the intricate web that connects art and entertainment, creativity and industry, and people and places, which enables him to forge peculiar collaborations with professional dancers and experimental musicians or pull off stunts like burning tires in the Arctic. Westphalen’s project in zingmagazine 24 draws attention to the absurdity that lurks just beneath the surface of the ordinary, and serves as a handy tool for artists and non-artists alike to grasp the power of this absurdity. He and I chatted via email about his creative influences, the art market, polar research missions, and bad jokes.

Interview by Hayley Richardson

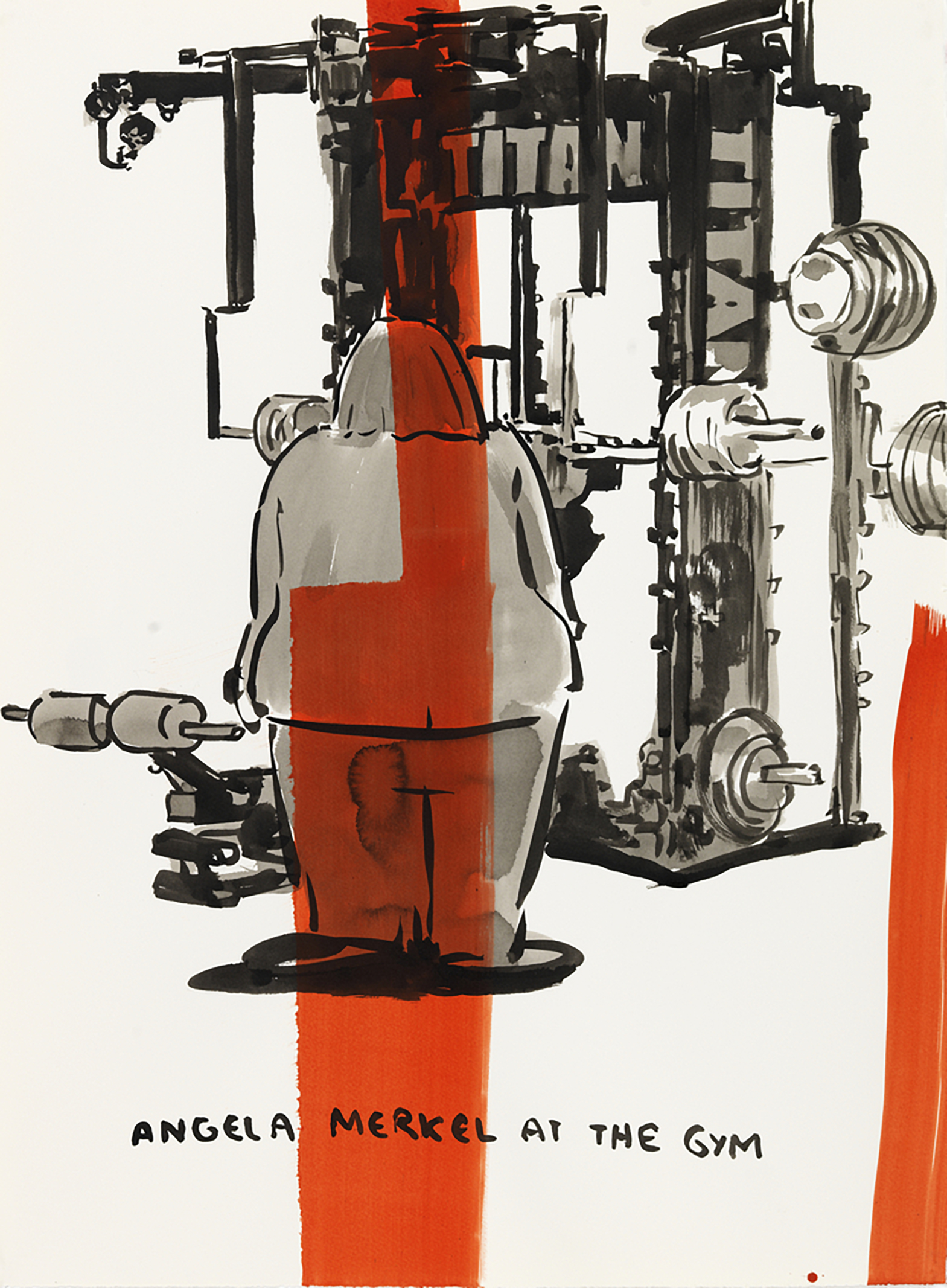

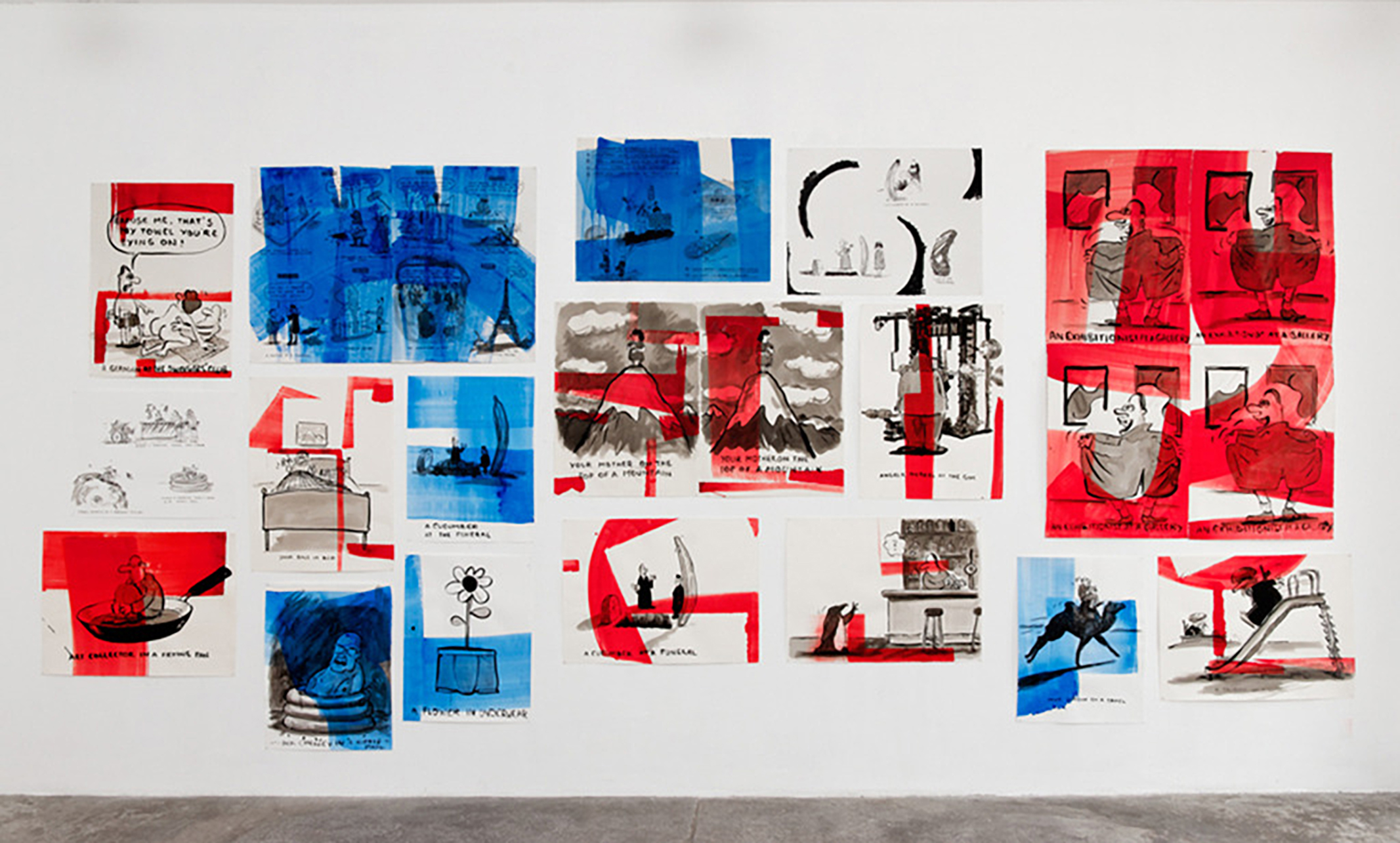

Your project in zing, “A junkie in the forest doing things the hard way,” was initially an exhibition of the same title at Galerie Georges-Philippe & Nathalie Vallois. It is interesting to compare the images on a page-by-page basis in the magazine to that of installation photos from the gallery. Can you talk about how your work fluctuates/relates to the presentation context?

I made this group of drawings, combining a super-standardized cartoon language with—equally standardized—big, gestural brushstrokes in bright colours. They had a very graphic appearance. When we showed the series at the gallery it made sense to arrange them on the wall in a kind of layout. The reference material comes from print media, so it wasn’t surprising that they suggested the printed page. That’s also why I thought this specific series was going to work well in zingmagazine.

Generally, I love printed drawings. It’s something about the tension between the accidents of the hand and the precision of the technical reproduction. What can get lost in print, though, with this specific group of drawings, is the painterly aspect of the large swaths of color you mentioned. They do affect you in a different way when seen on the wall, simply because of their size and saturation. The brush strokes are pretty silly design elements, but they are also just a square meter of cadmium red, which you will, at least for a moment, perceive as a sizeable stained surface with all the accompanying painterly connotations. This slightly perverse experience may be harder to get from the printed drawings.

The overall project (“A junkie in the forest doing things the hard way”) was a way to think about inspiration, wit, creativity, those rarefied instants in an artist’s experience, as mechanical processes, as industry. I often felt that creativity was a type of mechanism. Certain elements, relationships and criteria are brought into play. It could be a given form, like the limerick or High Modernist painting. It could be a given content, material, or several of these elements. And then, in quick succession, random data is run through this arrangement. I think the difference between the formalized brainstorm at a creative agency and a poet waking up in the middle of the night, her heart aching with a deeply felt new image, may not be a categorical difference, even if the results differ a lot.

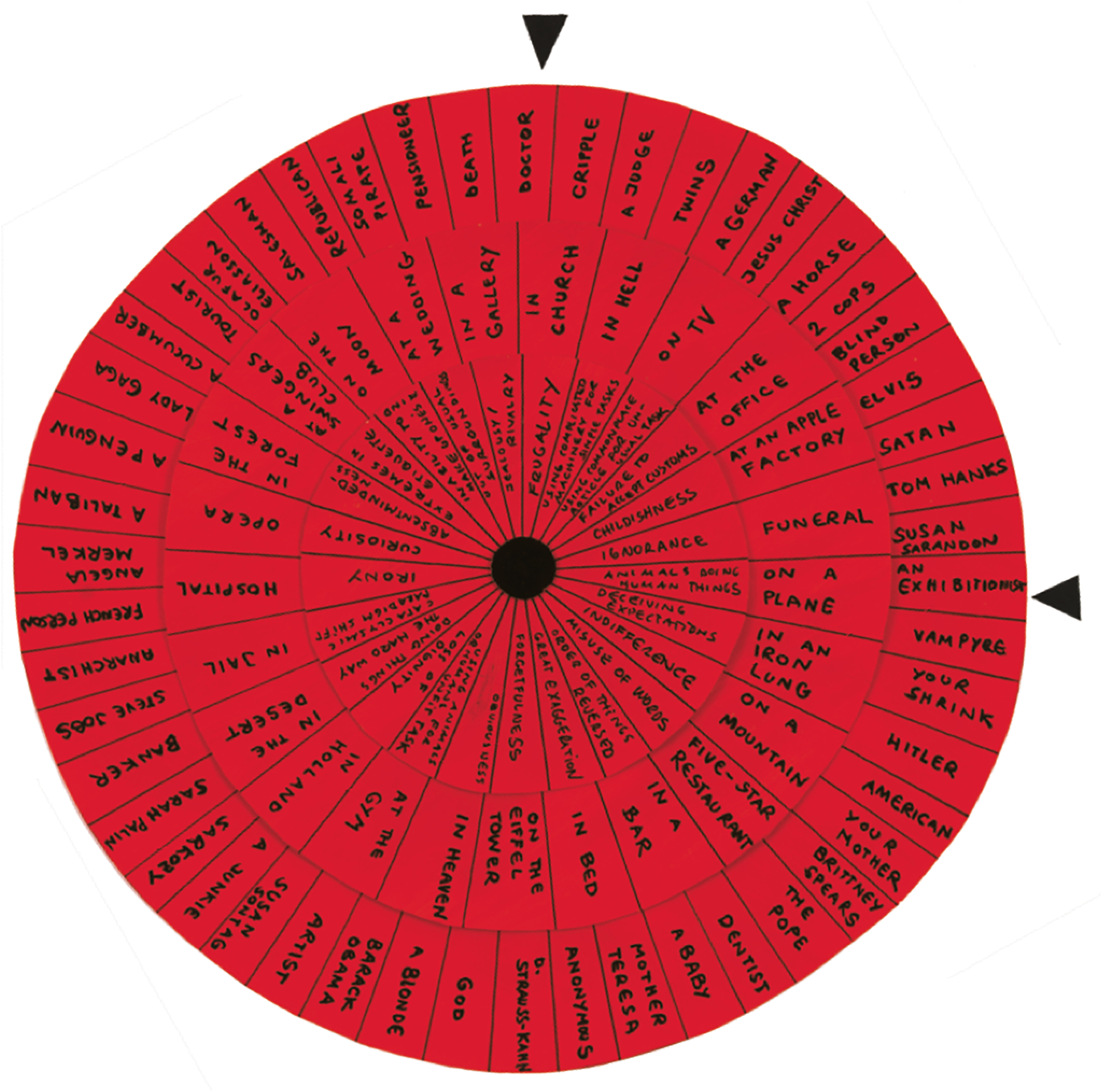

Glenn O’Brien wrote a great text, “The Joke of the New,” in the catalogue for Richard Prince’s show at the Whitney (in 1992). In it he mentions the cartoonist’s gag wheel, an aide for newspaper cartoonists invented in the 1930s. It’s made up of three concentric discs, which you can spin to line up randomly. The innermost wheel lists 25 types of comical situations. The center wheel lists 25 standard settings and the outer wheel 50 characters. This generates over 30.000 unique gag-premises. I loved that, and I made a whole set of wheels with different types of content for myself. I’ve used them in a cartooning workshop. They worked wonders for inexperienced cartoonists. For the ones that are already doing good work on their own, the difference was less dramatic. I think they had already internalized these mechanisms and could run them below the threshold of awareness. They were probably running them all the time. You know, we’ve all met some incurable punsters. There’s one in every extended family. It’s like Tourette’s. They scan every bit of conversation for a possible double meaning. For those people every good pun comes at the cost of many embarrassing moments. I guess the difference between the tedious uncle constantly issuing awkward remarks and the professional comedian may just be selectivity, having the restraint to not blurt out all the bad ones.

I have used the gag-wheel with performance artists and it worked even better. It made a shocking difference to some peoples’ work, maybe because some performance artists overrate authenticity. They can have a bit of a rigid notion of what they are truly about. And that gets redundant. So, the cartoon elements of these drawings are all entirely generated by a set of customized gag-wheels. And they are not censored. In that way, I am totally the embarrassing relative. There are some excellent jokes hidden in the series, there are some really lame ones and there are a lot of premises that never made it to the punch line.

Page from “A junkie in the forest doing things the hard way” by Olav Westphalen in zingmagazine issue 24

The swath of solid color across each image is another interesting element. Can you describe the purpose of the color?

The gestural over- and under-painting was meant as a parallel operation only in a formalist vernacular: a totally mechanical, repetitive way of producing these sweeping, expressive marks. I wanted them to be a caricature of abstraction. I think a lot of contemporary, neo-formalist work, knowingly or not, has that type of relationship to its historical models. I guess there was also an intended nod to an idea Mike Kelley once laid out—I think it was in “Notes on Caricature”—namely, that modernism was characterized by two opposing movements towards abstraction: a movement towards the idealized, heroic abstraction of modernist painting and a movement towards the abject, grotesque abstraction of caricature.

Installation view “A Junkie in the forest: doing things the hard way” at Galerie Georges-Philippe & Nathalie Vallois, Paris, 2012. Image courtesy of the gallery.

You are frequently associated with artists like Paul McCarthy and Mike Kelley. Which artists working today do you feel a strong connection with?

I like Mike Bouchet and his work a lot. I think Jessica Hutchins is great and in some weird way I think of her as a moral authority, even though I haven’t spoken to her in over a year. I love Alex Kwartler’s paintings. Peter Rostovsky is great and we have been friends and regular interlocutors for many years. I have learned a lot from that. I think Roe Rosen is amazing, as are Joanna Rytel and Mike Smith. I think Lisi Raskin is great. She just allowed me to borrow/develop on an idea of hers (“A rocket a day”). Lately, I have been doing music performances together with Lars Arrhenius, which has been so much fun. And of course cartoonist Marcus Weimer with whom I’ve published comics and cartoons for decades now (under the name Rattelschneck) is a real influence. But these are all people I have in some way worked with, or with whom I have at least a tenuous personal connection. I could name some household names and historical influences, like Cage and Kaprow. But also Fischli and Weiss, Rosemarie Trockel, Georg Herold (Herold much more than Polke or Kippenberger). Andy Kaufman, Nicole Eisenman, Allan Sekula (weirdly), Christopher Williams (I think he’s quite funny). But the personal connections are more important. I have realized about myself that I am basically a provincial artist without a province. I am always most intensely involved with the stuff that happens right around me, wherever that is. Even if, as was the case with Stockholm, there wasn’t a huge group of artists who shared my interests to begin with. A lot of the people I work with in Stockholm aren’t in the art world. They are comedians and film-makers etc. I convinced the philosopher Lars-Erik Hjärtstrom-Lappalainen to perform with me. You develop some type of loosely affiliated scene.

Your music project sounds interesting. Are you a musician? Can you talk more about this?

Ha! I am probably the least musically inclined person you will ever meet. But I like writing and I like using my voice on stage. So, my contribution to “Lars & Olav” is mostly the written and spoken word. I am pretty serious about the texts. Lars is musically very good and writes both music and texts. When we perform the sound is mostly pre-programmed, with us singing, speaking, shouting out texts live while we stand around awkwardly. It has all the quaint stiffness of a fluxus performance, but some of the beats are so well-written that people kind of start to dance against their will, or at least bob around.

With your history of moving around so much throughout Europe and the United States, what location would you say gave you the most inspiration, creative energy, meaningful involvement, etc.?

I guess that would still be Southern California. I had met and worked with an artist from California back in Germany, and that basically got me interested in contemporary art as opposed to comics and cartoons and perhaps writing. Because of that connection I went to San Diego for graduate school, which was probably the most formative period for me as an artist. People had an attitude towards art, very serious AND very open at the same time, which I still find really important.

You draw cartoons in English and German, and exhibit and perform your Art around the world. Deconstructing the barrier between artist and viewer/participant is an important element in your practice. How does having such a diverse global audience, which you engage with directly, influence your ideas and process?

I am not interested in getting rid of the artist/audience divide. I am OK with that division of labor as long as it is explicit and precisely articulated. I have done a lot of pieces in which the audience becomes actively engaged, makes a lot of the decisions and may even take the work away from me, but it was always a matter of ethics for me to make it very clear, that I was playing the role of the initiator, host, game-master etc.

When it comes to different audiences, I think one of the reasons I have been so attracted to entertainment as material and form, is that it transcends a lot of cultural specificity. But, still, sometimes you connect and sometimes you don’t. That’s where art is different from entertainment. It can be really interesting to be completely misinterpreted. Bad entertainment can be good art and vice versa.

There’s a video of your “Even Steven” performance at Art Brussels. And in that video you say how much you love art fairs and the market because they help artists evaluate their own work and provide the financial means to foster their ambitions. Have you always felt this way?

Well, there was irony involved. I don’t know any artist who doesn’t find art fairs at least somewhat problematic. That doesn’t mean they don’t serve an important function. You know the expression: An artist visiting an art fair is like a cow taking a tour of the slaughterhouse?

“Even Steven” starts out as a location-specific stand up comedy. So, as I was invited to perform the piece at Art Brussels at that time, I did a stand up routine about art fairs. It kind of meandered between acerbic criticism and a naïve embrace of the phenomenon. At some point in the performance I confessed that I was tired of being smart and critical all the time and that I really wanted to do something beautiful. I asked a professional dancer on stage and he danced a modern piece. It was about that contrast. Very touching. Only I couldn’t just let him dance but asked him to let me to dance together with him and then I became kind of competitive, even though I really am not a good dancer at all, which devolved into awkwardness. Still touching, but differently so.

What’s your opinion on the recent record-breaking auction sale of Picasso’s “Women of Algiers”?

Is it ok if I don’t have an opinion on that? I mean, it’s been quite some time now that the top end of the market has lost pretty much all connection with about 99% of living artists producing art, thinking about art, developing art, having amazing and important ideas and conversations. So, every new price record is a little bit like reading that the universe is made up of 500 more galaxies than we thought. You know, to me it seemed really, really big already. Who really cares? We read a lot about the market. But if you think about how much it is about social and monetary criteria and how little it actually deals with important questions, what a relatively small group of people we are talking about, you realize that it is quite provincial in its own right.

You are currently teaching at the Royal Institute of Art in Stockholm, correct? What kinds of courses do you teach?

Yes, I am a professor in fine arts with a focus on performative practices. The school is still largely in the tradition of the European Beaux Arts model. That means I don’t teach regular courses, but I work individually with students. I have a group of 15-20 students whom I follow pretty closely in crits, group crits, study trips, exhibition projects. I do can arrange arrange seminars and workshops, but that’s usually based on my own and the students’ interests. I am finishing up a one-and-a-half-year research project on Dysfunctional Comedy, basically a series of public events and experiments on joke strategies in contemporary art. Like I said, bad entertainment making good art. We’ll publish a book about this together with Baltic Art Center. That’s one advantage of the academy, that some projects which might have been funded through that system. What else? Together with the painter Sigrid Sandström I have been doing a recurring journey, where we take students to the Swedish Polar Research Station. They meet the scientists up there. And end up making work under pretty extreme conditions. We’ll go back there this coming winter. I think the best teaching is if it’s an extension of what you would be doing as an artist or an individual anyway.

Have you made any work at the research station, or another place with extreme conditions? What has the response been like from students participating on these journeys?

I haven’t produced any finished work at the research station. But on another trip to the arctic, to Kirkenes on the Barents Sea, I did make a piece that kind of flopped. I had had this image in my head, before the trip, of a completely white landscape, almost like a blank canvas. And I thought wouldn’t it be great to burn a stack of tires there, so you would get this column of smoke rising up vertically, a black line dissecting the plane. When I got there the landscape was white, but with so much variation in it that this cartoon-formalist idea of the arctic didn’t really apply. I got some tires anyway and found someone with a van to drive us out to some frozen lake. When we burned the tires it got really messy and even though the smoke was nice and sooty and black, it never really rose up as high as I imagined. So, the video we shot made it just look like a really far-fetched and lonely act of vandalism. Afterwards we had to clean up all that scorched and melted rubber. I am not sure it was worth it.

With your practice involving different media and collaborations, I am curious what your usual working environment is like. Do you have a dedicated studio space, or do you have a more variable/flexible kind of arrangement?

I have an office and next to it a modestly-sized studio. Both are very close to where I live. That’s important, that I can go there whenever and not spend time in transportation. I use the studio a lot when I actually produce something, but then there are times, sometimes weeks, when I don’t really go there and just read or write or sketch and do work on the computer. Which can also happen at home or wherever. I am not a post-studio artist, but an intermittent studio artist.

Is there any medium that you have yet to experiment with that you would like to try, or become more acquainted with?

I just now produced a digital animation for the Thessaloniki Biennial. It is based on a series of drawings I made. I really like that malleability, that the drawings already suggest their manifestation as virtual 3D-objects in a film. I would like to use 3D-printing to translate some of the objects from that film into physical sculpture. That’s a plan.

Gag-wheel in issue 24

Being a humorist, do you have a favorite joke?

Comedy is highly contextual. It doesn’t easily survive being transferred to another situation. That’s when you shrug and say: “I guess you had to be there.” Jokes on the other hand are supposed to be portable comedy. They are like the easel-painting of comedy. They carry their context with them, or rather, they rely on such commonplace contexts that they become, relatively, context-independent. I am terrible at remembering jokes. But I once worked for a German TV-show as a gag writer and the head writer asked me the same question, what’s your favorite joke? And then proceeded to tell me his. And that joke I remember till today.

What was the joke?

His favorite joke went like this: There’s a guy walking out about town and suddenly he sees a penguin in the middle of the city. He takes the penguin to the nearest police station and says: Look, I found this penguin walking around on its own, what should I do with it? And the policeman says, “You have to take it to the zoo.” The next day that same policeman is out on patrol and runs into the guy who’s walking down the street with the penguin. He walks goes up to him and says goes: “Hey, what’s going on? I told you to take that penguin to the zoo.” And the guy goes: “I did that was yesterday, now we’re going to the movies.”

What do you have coming up in the near future?

I am working on two book projects and we’re expanding the repertoire of “Lars & Olav.” We are preparing for a performance at a club in Athens in September and decided to produce a new piece, a love story between a woman from Kreuzberg and a tour guide on Crete, titled “Eurolove.” It’ll be danceable Greek-German techno.

From Joshua Abelow’s project “Fourteen Paintings” in zingmagazine issue 24

Creative energy and instinct runs in Joshua Abelow’s family, passed down through the generations from his grandmother, his mother, and then to him and his sister. Growing up in Maryland, detached from the contemporary art world, this instinctual need to create art allowed him to develop a personal style based on the purity of form, the complexity of color, inferential reasoning, and a sense of humor. Abelow’s formal entrance into the New York art scene began just as organically, when gallerist James Fuentes discovered his work on Art Blog Art Blog, which Abelow started in 2010 as a means to get his art into the world. The blog not only allowed him to showcase his artwork alongside other creative figures he admired, but also served as an extension of his practice and as an artistic exercise with a distinct beginning and end. The blog inspired Abelow’s interest in curating, a role that is still very much tied to his work as an artist. Now with a project featured in the newest issue of zingmagazine, a series of paintings recently installed at Dikeou Collection, a gallery space in Baltimore, and an upcoming show at James Fuentes Gallery, 2015 seems to be the year when all his creative endeavors will coalesce more potently than ever.

Interview by Hayley Richardson

Where are you right now?

I’m in a gigantic hay barn that I rented to make large paintings for the summer in Maryland, where I grew up.

When did you move into the barn? When did you start doing this?

I started doing it last summer. I found this barn on Craig’s List sort of by chance. I was home visiting family and was just messing around on Craig’s List to see what might be available in terms of studio space and I got lucky. Last summer was great and I couldn’t stop thinking about it so I decided do it again.

How big are the paintings you’re working on right now?

I’m working on a series of paintings that are 98 inches by 78 inches. Last summer I made 80-inch by 60-inch paintings and then a few other ones that were a little bit smaller than that. You know in New York, everything is so . . . you know there is a different energy out here which is kind of great because there’s obviously the space and the head space, but then there’s also, you know, there’s like ducks and chickens running around. It’s the complete opposite of working in New York.

Are you still working in a similar style, with your geometric backgrounds and color patterning?

That kind of geometric work is ongoing. It’s like a daily ritual and keeps me busy no matter what. But also this past winter I focused on a lot of drawing, and now some of these larger paintings are based on the drawings.

In your curatorial statement for the latest issue of zing you wrote a poem, and I am curious how you would characterize the interplay between your poetry and your visual artwork.

I think there’s definitely a relationship, and maybe sometimes it’s more obvious and sometimes it’s not as obvious but everything I do is connected. The poems are diaristic. I used to keep handwritten journals, but then the blog replaced that and the poems are a way for me to continue messing around with words. There was a time a few years ago that I was only painting words. The relationship between text and image continues to interest me quite a lot.

In the poem you say that the pictures were inspired by dancing figures in a movie. Is this a literal statement, and if so what movie was it?

It’s not really literal, it’s more metaphorical.

What’s the story behind the “Famous Artist” paintings in your zing project?

There’s a Bruce Nauman quote that’s been stuck in my mind for years—referring to one of his neon signs he says, “It was a kind of test—like when you say something out loud to see if you believe it. Once written down, I could see that the statement was on the one hand a totally silly idea and yet, on the other hand, I believed it. It’s true and not true at the same time. It depends on how you interpret it and how seriously you take yourself.” I did a show called “Famous Artist” in Brussels in 2012. I had never done a show in Europe and I thought the title might get people’s attention, which it did

We recently installed “Call Me Abstract” at Dikeou Collection, a series of 36 paintings with your cell phone number. Visitors have called this number and left voice messages for you. Have you listened to them?

Yes, I have. I’ve gotten a number of phone calls and some text messages. If I don’t pick up the phone I always listen to the message and sometimes I might respond with a text. I started developing the “Call Me” idea in early 2007. The first paintings just said “Call Me” and then I wanted to literalize that idea by painting my phone number. One time, actually more than once, a professor called me up and put me on speakerphone with his class while I was eating lunch. And you know that’s kind of the idea—to create an unexpected situation with painting.

“Call Me Abstract” is painted on burlap, as well as a few other of your paintings. Why did you choose to start working with this material?

I paint on burlap, I paint on linen, I paint on canvas. I’ve experimented a lot with all kinds of different materials. My work is often systematic and pre-planned, and so the burlap, because there’s a great texture to it, it butts up against the paint in interesting ways and there’s always room for the paint to do something unpredictable like bleed. I buy the stuff at Jo-Ann Fabrics and I can tell that the people who work there wonder who this guy is showing up to buy burlap all the time.

I was looking at some of your new work on your website where you have reproductions of modernist works by artists like Magritte, Kirchner, and Pollock with the Mr. Peanut character inserted into it. Could you discuss what these are about?

That’s a specific body of work that I produced for a show that I did with two artists in Brooklyn recently at this gallery called 247365. The show was called “Situational Comedy” and it featured work by me alongside Brad Phillips who is based in Toronto and a guy named R Lyon who lives in New York. The whole idea was to put together a show of work that might not look like other work we’ve made, or at least that’s how I was thinking about it. One of the things that was funny and interesting was that at the opening people would come up to me and say, “Hey, we know you’re in the show, where’s your work?,” and I would be standing next to one of the pieces. There’s a performative element to a lot of what I do and the conversations at the opening seemed to embody the spirit of what I was trying to do. Mr. Peanut is basically a stand in for me. I wanted to take out my hand all together and just make something from appropriated imagery. I was thinking a lot about Kenneth Goldsmith’s “uncreative writing” ideas. Eliminating my hand changed the decision-making process and put more emphasis on placement and scale. Those works are really small—a little larger than postcards.

I’ve read that Magritte in particular is very influential on you, so I understand why you would use one of his pieces. Could you talk about the other artists that you included?

All six images that you’re talking about were taken from art books that I’ve collected over the years and those are some of the images that I keep around the studio and look at all the time. When I make drawings I often lift material from these art books. Another thing I like about the Mr. Peanut works is that they are reproductions of reproductions of reproductions so the content of the work is layered and not as straightforward as it might appear. This interest in reproduction was something I explored in my blog for five years and those Mr. Peanut pieces are strongly related to the blog, and in a way, the end of the blog because I stopped running the blog around the time of the opening.

Your drawings generally have a more fluid and varied appearance than your paintings, and have a distinct lack of color. To me they are reminiscent of drawings by people like Warhol, Jean Cocteau, and Picasso. The drawings and paintings share certain aesthetic tropes like the stick figure, running witch, and use of text, but they seem to be coming from a very different place in your mind than the paintings. I’ve even noticed that the paintings and drawings are exhibited separately from one other in galleries. Can you talk about the relationship, or even the dividing factors, these two mediums have for you?

Yeah, I think a lot of what you just said is totally true. In simple formal terms, with drawing, I’ve always been interested in line and gesture, and with painting I’ve always been more interested in form and color and shape. Most of the solo shows I’ve done have featured drawings and paintings but not side by side. My first show in New York was at James [Fuentes Gallery] in January of 2011 and I, very intentionally, set up a situation where I had small paintings on the left side of the room and on the right side of the room I had my drawings. The idea was to create a situation where the drawings on the right side of the room would essentially undermine or argue with the logic of the paintings on the left side and vice versa. In the drawings I was satirizing the idea of the “painter” in the spirit of Paul McCarthy’s piece “PAINTER.” I wanted the entire exhibition to function on a satirical level. It was sort of up to the viewer to come in and determine what was going on and to try to make sense of it. I’m always thinking about that kind of thing in my work – I’m always thinking about the relationship between things – the relationship between paintings and drawings, or the relationship between, say, a geometric painting next to a painting that has my phone number on it or a face or some other figurative reference. And I am interested essentially in storytelling, but a kind of abstract storytelling where the viewer really has to do legwork and get mentally involved.

So you’re bringing them together more? Would they be exhibited in an integrated way like that too?

Well, like the running witch that you brought up before, I don’t know if you’ve seen too many of those paintings because it’s a relatively new image that I started developing last summer and that came directly out of drawing. And even the stick man with the top hat and the funny dancing shoes, that came out of drawing, too. So there are moments when the paintings and the drawings gel and then there are moments when they dissipate and don’t look anything alike. I like that fluidity, I want there to be that kind of openness. I think of it like experimental music – rhythms going in and out.

You come from a family of artists. Your sister, Tisch, is a painter, curator, and blogger. I’ve noticed that her paintings have a similar emphasis on geometric formality and color interaction as yours do. Can you talk about what kind of influence you two have on each other’s work, or life in general?

Yeah. I think my sister and I were both influenced by our grandmother who is a really wonderful painter. She’s 92 years old and lives and works in West Virginia. She studied at Cooper Union back in the late ‘40s, but she never pursued a career as an artist, and I don’t think that was even an idea that would have been remotely possible for her at the time. But we grew up with some of her paintings and drawings in the house and she had her work up at her place, and I would say her work is reductive . . . it’s based on observation but it’s definitely reductive—shape, color, line. So, I would say that my sister and I are both indebted to her. My sister originally wanted to be a writer (like our mom). She went to Sarah Lawrence to study creative writing and didn’t make her way into painting until later. In fact, I think she actively avoided painting for a long time because that’s what her older brother was doing and she wanted to do her own thing. When she was a senior she took a painting class and started painting at that time and has really kept it up since then.

Yeah, I’m almost thinking of like this genetic thing that’s embedded in you guys, that you sort of share this aesthetic between you all that just grows through the generations. Like if one of you two had kids one day you could see it manifest again in some other way.

Absolutely. In 2013 I published a monograph called Art Fiction with reproductions of my work alongside some images by my sister and images by my grandmother. My sister and I showed our work together at a small artist run space in Philly back in 2010, and my grandmother and I exhibited together at the Prague Biennial a few years ago, and that opportunity led to a small solo presentation of her work at a gallery in Milan called Lucie Fontaine. My sister and I went over there for the opening. My grandmother couldn’t go but she was excited about it anyway.

In 2010 you started your Art Blog Art Blog where you posted your poems, as well as excerpts from books, information and images about other galleries, shows, and artists you were interested in. It was updated constantly; averaging 2500 posts a year and had a sizeable following. Why did you decide to stop updating the blog this past March?

You know there’s another interesting Bruce Nauman quote that I wanted to get into this interview. This one is taken from an interview he did in 1978, and he says, “Art is a means to acquiring an investigative activity.” And that kind of thinking is what got me started with the blog. Unlike other blogs, I was thinking of my blog as a form of artistic activity, and so in other words it was always intended to be an art project in and of itself so therefore it would have a start and it would have a finish. When I started it I wasn’t sure how long I would keep it up but when I hit the five year mark it felt like a good time to stop because otherwise I think I would have wanted to do an entire decade and it was too much. I felt like I made the point after five years. It didn’t really seem necessary anymore.

It seems like with how much you interacted with it, it seemed like something that was really part of your routine. Was it strange when you stopped doing it? Did you have to remind yourself, “No, I’m not blogging anymore. I’m not doing that today.”

That’s a great question. The thing that’s really strange about it all is that there was a lot of nervousness on my end leading up to the end, but after I finished it I felt uncomfortable for about an hour or two. I look back and I can’t even believe I spent that much time doing it. I don’t even think about it now. It’s weird.

Yeah, that’s kind of surprising to me actually. I figured it would have been something that you would have been more attached to as far as seeing something and being like, “Oh, that’s cool I’ll put it on my blog. No wait, I can’t.”

Well you know what saved me was Instagram.

Yeah, that’s what I assumed. And that leads into my next question: Looking back at an old interview in a 2012 with Frank Exposito for James Fuentes Gallery, you mention a self-portrait you made in 2003 with a television on your head, and related the artist and the television as transmitters and receivers of information. As an artist who uses the internet heavily, especially with Instagram now, do you think the computer is now the more dominant force in this exchange, or does the television still maintain the same power you attributed to it 12 years ago?

Hmmm, I definitely think it’s all about the computer. I think in that interview I said “television” and I meant television basically because at that time when I made that work, it wasn’t immediately following 9/11 I guess but it was in the wake of that, and I was living in New York not far from where that happened. And I think every artist and every person in New York and elsewhere was trying to grapple with what happened, and it’s like how do you make something, how do you make a painting or a meaningful artwork when an event of that magnitude has happened. So basically for a long time I was leaving my television on watching the news nonstop and I started making work again with the TV on and I was watching TV all the time while I was in the studio. But with the TV, when I said it, I meant it more metaphorically like the way we connect to technological devices to get information and having this connectivity has changed the world and continues to change the world.

Yeah, and I saw that when we posted “Call Me Abstract” on Instagram you were instantly engaged with it and put it on your blog right before it ended, so I thought it was kind of cool that connection was made at a somewhat crucial time because it was just really days before you ended the blog so it was kind of cool that it made it up there at that time.

It’s also, I mean, the phone number piece at Dikeou is coming right out of the same kind of logic as the painting you’re describing with the television on my head. It’s this idea, with the phone number, it’s a self-portrait in the technological age—like these numbers signify me. Even beyond that they signify New York…anybody who’s lived in New York knows that it’s the 917 number, it’s a New York phone number, there’s this relationship to the idea of “the New York artist” which is really intentional because if I didn’t have a 917 number I don’t know if I would have even…I might have made something else. I wanted those numbers to signify a bunch of different things but in the most basic abstract way.

Yeah, I can relate to that because living in Denver I don’t have a Denver area code on my phone number and so when I share my phone number with people it immediately brings questions like, “Oh, where’s that from? How long have you lived here,” that kind of stuff. So it is definitely tied with your identity.

Definitely. And you know I think that’s also young artists, or artists of any age I guess, who are moving . . . I mean I always say New York and I don’t know if it’s old fashioned or not but I still feel like New York is where (L.A. too) artists still want to go. You know young artists are moving there out of art school to go make an identity for themselves, you know, so this idea of a 917 number, a New York number, it’s something so many people can identify with. It’s like that same thing if you’re from Maryland or wherever and you move to New York and get a New York state driver’s license, it’s like the birth of a new identity.

In another 2012 interview with Matthew Schnipper for The Fader, you made a comment about there being a growing number of people who make art as a career whereas you make art out of necessity. You’ve been quite fortunate, though, to make a living doing what you love. Do you feel like the “career artists” make things more challenging for the ones working out of pure passion? How do these two types of artists interact with each other, or how do you see the differences in how they navigate the art world?

Hmm…well, I think of myself as a late bloomer. I didn’t have my first show in New York until I was thirty-four, which by today’s standards is on the late side. Many of my peers started showing way before I did and I just plugged along. Now I feel much more connected to younger artists—a lot of the artists I talk to the most are a decade younger than I am and I like that actually. If I’d grown up in New York City with parents who were in the art world and taking me to all the art openings and if I had been exposed to the world of contemporary art at a young age, then I’m sure I might not have felt that pursuing art was going to be like climbing down into a dark tunnel for the rest of my life. But in Maryland where I grew up that just wasn’t the way it was—when I told people I wanted to be an artist they just looked at me blankly and I could tell they felt sorry for me. I didn’t know anything about contemporary art or that you could make a living as an artist, really. I wasn’t thinking about it from a practical stance—I just knew that I was an artist and that I would do whatever I could to keep the world from robbing me of what I felt compelled to do.

Would you say that you’re surprised at all by your own success, or expect it to grow into what it’s become now?

I think being an artist is a gamble. I think what happened with me is that a real shift in my thinking occurred when I was in graduate school I stopped thinking of myself as a “painter” and started to think of myself as a person involved with art as an activity in a broader sense. I got interested in Peter Halley’s writing and I became more aware of the role that art can have on a social level. And that really opened up a lot of doors. I’m happy that I have been able to carve out a space as an artist and I want to continue to push the work forward and work hard.

Can you talk about your background/experience as a curator?

Curating came out of Art Blog Art Blog and Art Blog Art Blog came out of my studio-work so I think of curating as an extension of my studio. I think that’s really why I started the blog—thinking a lot about arrangements of things. The other thing about the blog is that when I first started it I was not showing my work much, I didn’t have gallery representation, I wasn’t even living in New York at the time, and so it was a way for me to contextualize my own work alongside the work of other artists and whatever else in any way that I wanted. If you go back into the archive, the first year or so of the blog is primarily images and a lot more of my own work and my own poems in there because I was trying to get some visibility for myself. It was surprisingly effective. Less than a year after starting the blog I started working with James and suddenly there were a lot of eyes on what I was doing, and so I kind of backed off a little bit on featuring my own work on the blog and became more interested in showing work by other emerging artists. It was an exciting time in NYC because the market had crashed and there was a lot of DIY energy in the air and I think ABAB captured that energy and harnessed it to an extent. I started showing work by famous artists, both living and dead, alongside someone like a 23 year old that I met in Brooklyn and did a studio visit and thought their work was interesting and it might have some kind of obvious or not so obvious relationship to, let’s say Magritte or whoever. And then I would put it online and allow the viewer to make these visual and conceptual connections. It was so amazing to feature certain artists—you know I would promote certain people on the blog and the next thing you know they’d be showing all over the place. I had a strong hand in it that, although I didn’t really expect the blog to have that much influence. That happened organically. But yeah, that’s how I got into curating.

Is curating something you would like to continue to do?

I’m running a semi-anonymous space in Baltimore. Right now we’re on the tenth show. It’s been interesting, it’s been a way for me to sort of crystallize a lot of the thinking that went into Art Blog Art Blog—a more focused version because the gallery is named after Freddy Kruger, and all the shows are sort of dealing with . . . there’s a kind of dark humor vibe to the shows that we’re doing.

What are you currently reading, listening to, or looking at to fuel your work?

Keith Mayerson sent me Eric Fischl’s memoir, Bad Boy, which I have been enjoying. I’m half way through it. And the chickens and ducks, those guys are the true inspiration.

What else do you have coming up in the near future?

I’m working on a show for Fuentes, which I think is going to be in January. I don’t want to say too much about it because I want it to be a surprise but I will say that it’s going to be a multifaceted show with an Internet component.

Last fall I did a two-man show with Gene Beery, and I interviewed him when I did my first Art Blog newspaper. Gene is a text-based painter who also messes around a little with video and photography. Gene has been a huge part of my blog—an active contributor for at least two years, and when I knew the blog would end Gene and I did a countdown—everyday he’d send me a new image that said something like “14 days remaining” or whatever with a design. Anyway, Gene is an under-recognized artist who is one of my heroes and so it’s been amazing to have this ongoing web-based collaboration with him. And last fall our collaboration was translated into a two-man show at this artist-run spot called Bodega in New York and at Freddy in Baltimore. Now we’re working on collaborative silkscreens. I don’t know where the silkscreens will end up yet but I just wanted to talk about it for a minute because I’m pretty excited about it.

Bowery Nation, Installation View, The Aldrich Contemporary Art Museum, 2012

Brad Kahlhamer walks the line between worlds. Or better yet is continually creating a path of his own—a “third place” where imagination and identity are joined at the hip in a patchwork of Native icons, punk vibes, pop reference, all dripping with the language of expressionist gesture. Born in Tucson, Arizona, Kahlhamer has been in New York working across mediums since the 1980s—first as a design director at Topps Chewing Gum and soon an artist in his own right navigating the energies of Lower East Side, a mythic territory since woven into his evolving visual narrative. Today we find Kahlhamer coming off high-profile exhibitions at Chelsea’s Jack Shainman Gallery and a residency at the Rauschenberg Foundation in Captiva Island, now immersed in the role of Brooklyn’s flaneur and on the verge of a trip to Alaska. Most recently, Kahlhamer contributed an essay to the catalog for Fritz Scholder’s Super Indian exhibition, opening at Denver Art Museum in October. I met Brad at his studio in Bushwick to discuss underground cartoonists, hardcore bands, the art world, Native culture, sketching, and the one dream-catcher to rule them all.

Interview by Brandon Johnson

You’re about to depart for Alaska?

Next week. I’m doing this thing called First Light Alaska Initiative. I’m one of six people who are going up to conduct workshops on two weekends. Then we are going to hold over in Anchorage. I hope to get some fishing in if it’s not too cold or iced up.

What are the workshops?

It’s a woman named Anna Hoover who’s taken it upon herself to create a workshop and eventually a brick-and-mortar space. She’s bringing up a number of people. One, a “gut-skin sewer,” which is the old way of making clothes out of seal intestines. There’s also a chef coming up, and a musician, all from upper Alaska and Canada. We are traveling together as a Native entourage.

How long are you there for?

Eleven days. That’s a pretty good amount of time. I’m going to bring sketchbooks, do a lot of thinking. Just take it all in since I’ve never been up there.

Now let’s return to the beginning. How did you get involved with art making?

I came to New York in the ‘80s and worked at Topps Chewing Gum for about nine years as a design director. I was working with a lot of underground cartoonists like Art Spiegelman, who created Maus which became a really big deal. Others included Mark Newgarden, Kaz and Steve Cerio—it was a full immersion in the downtown creative world of that time. But I was also making watercolors at lunchtime and scavenging for sculpture materials on the Brooklyn waterfront where Topps was located. I finally quit Topps in ’98 to go full on with my own art and it seemed like the next day I was asked to be in a show in Amsterdam.

You were making your own work during your time at Topps?

On and off—I was cobbling together pieces as much as I could. I was putting together these giant sculptures out of rubber tires, these kind of impossible, belligerent things—dark, bleak, and black that summed up the Lower East Side at the time. I was also playing in a band. I recall we played with the Cro-Mags and people were throwing beer cans at us. It was all part of the experience.

You were in a hardcore band?

Well, we were in a hardcore show at Danceteria. At the time we had a rehearsal studio on Ludlow next to Bad Brains’ space and our lead singer knew a couple people around that band. Anyways, Ludlow Street had a lot of that history. So that was exciting. In ‘96/97 I started showing with Bronwyn Keenan and her start-up gallery downtown. In ’99 I was introduced to Jeffrey Deitch who had this idea to dedicate part of his gallery to the expressionist painting that was going on at the time.

And you were part of this grouping?

Yes. I was seeing myself as a next generation New York painter. I had been painting brushy expressionistic oils, not a popular direction at the time. The canvasses were smallish, probably due to finances and limitations of studio space. But Jeffrey had this idea. He was seeing yet another resurgence of this type of painting and brought me into the fold. There were to be four of us—one of which was Cecily Brown (who later went on to Gagosian). I stayed with Jeffrey and did three shows. The first was in ’99, “Friendly Frontier,” which was just a great experience and made me realize a broader context of the New York art world. Jeffrey was really looking for artists who were able to conjure up and present an entire universe and there were a number of us who were doing that at the time.

First Blast, 67″ x 64″, oil on canvas, 1999

Is creating your own universe something you sought to do as an artist?

No. I’m fairly natural in my production. I try not to over-think things. The idea of mating Western, Native American mythology and history with downtown New York created a world necessary for me to exist—a world I call the Third Place. The First Place being the life I would have lived had I not been adopted and the Second Place being the life I actually do live. The Third Place was the intersection of all my passions, the artwork, and the reality I created and was living. Jeffrey recognized that a number of people had similar visions at that time and picked up on that. Really exciting time to be showing. First of all to be living and working in downtown post-’80s and second to be part of the Deitch experience. I don’t know if that sort of thing can even happen anymore—the amount of experimentation was pretty remarkable on the scale that he offered.

Do you feel that post-Deitch you’ve had to seek a new direction?

It was such a moment unto its own. When that all ended there was a regrouping that had to happen. The outside world was also changing in New York with the economic collapse. It wasn’t just me, it was everyone. Everyone was scrambling, It was a time of changing and shifting. Yeah, it seems like 2008 was the year referred to over and over.

What was your situation in 2008?

I had always been hardwired to make art since I was a kid. You can retrench but it’s not like I’m not going to be an artist. I learned a lot during that period and became more self-sufficient. It’s all worked out. Jack Shainman approached me and we’ve taken it to the next level—in Chelsea now as opposed to downtown.

When I was in your studio last to put together the zingmagazine project, you showed me images from Bowery Nation, which I think eventually ended up being shown at Shainman?

Jack showed that piece in October 2013 just after I joined the gallery. It had already been acquired by Francesca Von Habsberg and TBA21. Jack borrowed it for the show, “A Fist Full Of Feathers.” Super generous of him to bring it to 24th street where the New York Times and a number of others reviewed it.

I remember you had it shown at the Aldridge Museum prior?

Yes, I completed Bowery Nation in 2012, capping it at a hundred figures and twenty-two birds. Richard Klein brought it to the Aldridge Museum and then it immediately went on to the Nelson-Atkins and their beautiful building, and soon after to Jack Shainman’s 24th Street space in New York, and finally ending up in Guadalajara at the MAZ (Museo de Arte de Zapopan) where it’s currently awaiting transportation to Bogota. Bowery Nation is going to be on the road for a while, which is thrilling. Guadalajara in so many ways reminds me of the Southside of Tucson, which is where I grew up. So it was cool to see those figures in an environment similar to where I came from. Growing up in Tucson, I was aware of the Heard Museum in Phoenix, Arizona. Around 1975 or so, I was visiting the Heard and for some reason the Barry Goldwater collection of kachina dolls made a huge impact on me in sheer number and quality. That’s a whole cosmology unto itself. Later, in the mid-90’s, I saw a Pow Wow Parade at Crow Nation in Montana, and subsequently created this conceptual Pow Wow float, which is why Bowery Nation looks like it does. I basically assembled my studio furniture and built an improvised platform. My idea was that anyone could do this and take part in the parade. These were the intercessors and ambassadors of this creative universe. It had a noise level that I really liked.

Was there any specific inspiration for the individual figures?

Again, going back to the Topps Chewing Gum experience, there was the anthropomorphic nature and characterization within the comic worlds. Combining that with things I had seen in the Heard Museum—the overall human idea that the doll or figure is translating myth and history to a younger generation is a universal concept. It seems to be a natural from time immemorial. The next level of figures I showed at Jack’s gallery in “Fort Gotham Girls + Boys Club” are more involved in articulation with their own dream-catchers. Recently, I was at this incredible residency in Captiva Island, Florida at the Robert Rauschenberg Foundation. There was a kiln and so I started picking up clay and building forms. That seems to be a huge new direction in translating my painterly impulses into my need to build objects.

How do you feel your work relates to Native culture? You are clearly interested and purposefully seek it out. But there also seems to be a rift.

That’s an excellent question. I’m currently in this show called “Plains Indians: Artists of the Earth and Sky” at the Met. It’s hugely important—spanning two thousand years of Native cultural history to evolving contemporary Native work. I feel great about being in it, but it’s also making clearer my position in relation to Native culture—this kind of inside, outside thing. I’ve created this bubble for myself and the show is bringing that more into focus. It was a very direct and conscious decision that I occupy a unique position in relation to both the Native and the contemporary art worlds.

And it makes sense because Native culture has been so interrupted historically. You’re not trying to preserve traditional culture but instead representing this position you’ve sort of found yourself in.

In my talk at the Met, I refer to it as a “collision of cultures.” When you see the show it is fairly clear from the late 1800s on. My work is more like you’re driving along and come upon the immediacy or suddenness of a car wreck that hasn’t quite been cleared off the highway. That’s not the most typical narrative.

That segues nicely into your zing project in issue #23, “Community Board”—a montage of images from photos to drawings, found pieces, and video stills.

Yeah, it’s beautifully designed. I love the way it turned out. There’s an incongruity or uneasiness from image to image, much like how the Plains ledger drawings work. Spatially, in the ledger drawings, multiple events occur within one page. When you think about it, some of them are more progressive than comics today. Ledger drawings were America’s first graphic novels.

What are you working on now?

The sketchbooks started last summer, reconnecting to a tradition I’ve always followed. It was this idea of drawing the new orbits of creative activity around Bushwick and Williamsburg. It’s based on the older tradition of the flaneur—the Parisian artist roaming the streets and recording. I think it’s just extending the studio practice out and beyond. Having a glass of wine with dinner at night and sketching. Keeping it going. It’s really that simple. That’s the beauty and brilliance of the sketchbook.

Does this feed into other work, like your paintings?

Well, traditionally, that would have been the case but now I’m posting them on Instagram (@bradkahlhamer ), which led to a show at the Wythe Hotel of selected spreads in three of the penthouse rooms. Suddenly the sketchbooks have their own life. I like the public/private nature of this exhibition because it goes back to the intimacy of the sketchbook as well. It’s the grand tradition of observational drawing. I’ve always drawn the figure. The reason I sketch is to drive up the intensity of the experience and make it more known to me. It’s natural for me to not make one but 248 drawings of, let’s say, skulls for my Skull Project (2004). It comes out of music because I play by ear and it was always the idea of repetition of learning that was ground into me as a teenager.

SuperCatcher, 11.5′ x 11.5′ x 12″, wire and bells, 2014

Tell me about your latest work, SuperCatcher.

The idea was to take every dream-catcher in the United States, whether it’s on a pickup truck or in a single-wide trailer, somebody’s bicycle or baby crib, and weave them all together in a cosmos, a universe of industrial wire. The spiritual rebar for an enriched dream reactor. I’m very pleased this particular work will be hung at the 2016 grand re-opening of SFMOMA.

Find more about Brad Kahlhamer on his website www.bradkahlhamer.net. View his new music video “Bowery Nation” here and follow him on Instagram: @bradkahlhamer .

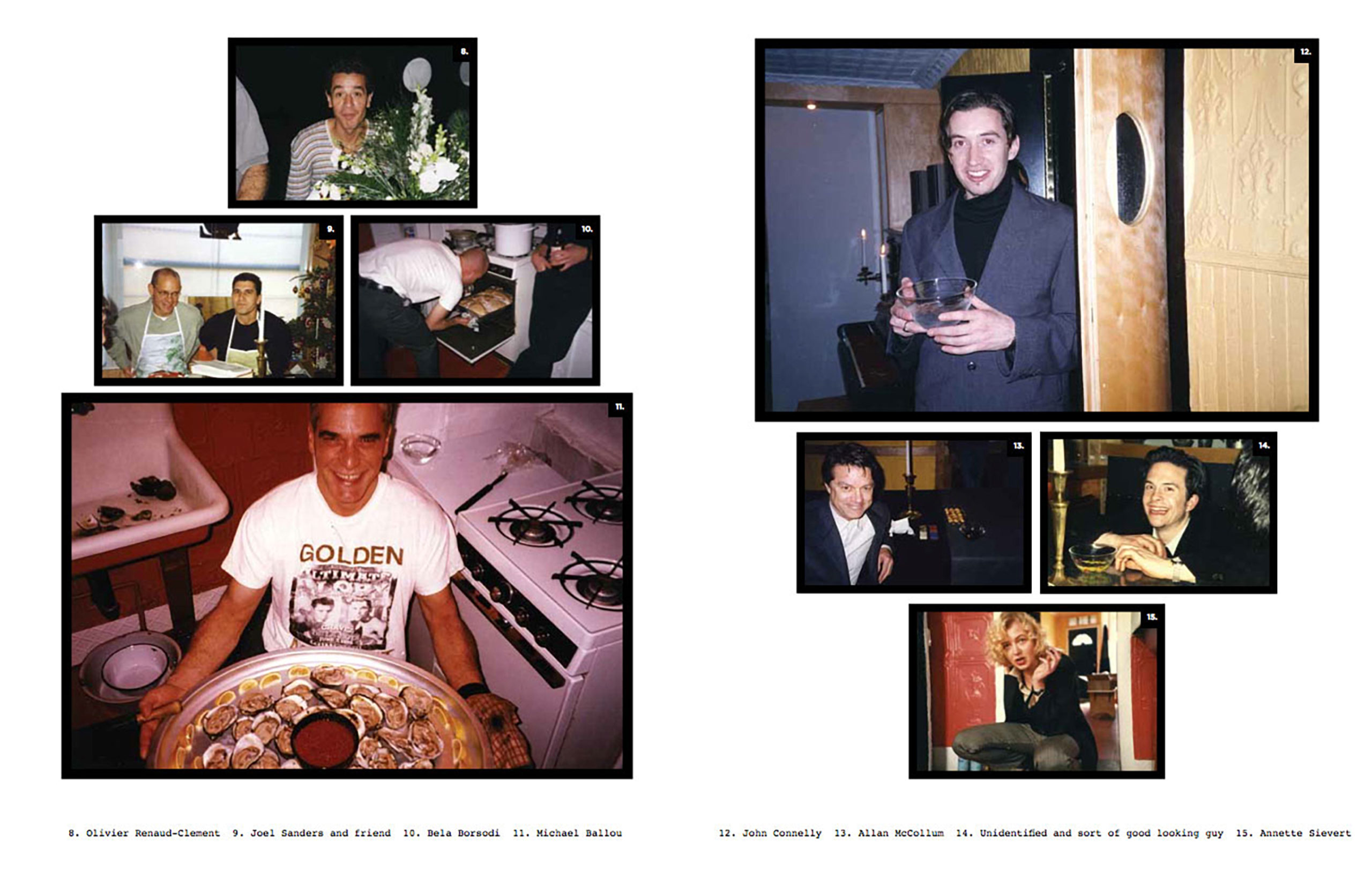

A page from Cocktail Hours at The A-Z Brooklyn NY 1996-1998, curated by Andrea Zittel for zingmagazine 23

Andrea Zittel casts a critical yet sensitive eye upon society and its constructs. She questions the value and implementation of social design, both the psychological and physical, and aims to provide insight and solutions to these questions through her artwork. Her investigations have culminated into an incredible range of artistic output, from modular living units, egg incubators, and functional textiles, to the creation of floating islands, desert communes, and interactive public art installations. The nature of Zittel’s artwork calls for utility and interaction, but simultaneously values aesthetic autonomy and personal solitude. This dichotomous relationship between form and function, public and private, is indicative of how her work effortlessly straddles the lines between art, architecture, and design. Her project in zingmagazine issue 23 documents the usage of some her early prototypes, and provides a glimpse into her social circle of the time. Rachel Harrison, Wade Guyton, Maurizio Cattelan, Gregory Volk, Roberta Smith—these are just a few of the people who could be found in Zittel’s three-story row house on Brooklyn’s Wythe Avenue on Thursday evenings, in a time before the borough became the creative hub that it is today.

Andrea and I began to exchange emails back in March, when she was in the midst of organizing and installing an exhibition of her “Aggregated Stacks” at the Palm Springs Art Museum. In April she welcomed the first of two groups of people to her A-Z West outpost for open season in Joshua Tree, California to facilitate their personal explorations in art, life, and self. She is currently preparing for another solo exhibition, The Flat Field Works, at the Middleheim Museum in Antwerp. Her ability to maximize efficiency and productivity is something we all strive to achieve, but her capacity to do so creatively and philosophically is beyond exceptional.

Interview by Hayley Richardson

Your A-Z enterprise began in a small row house in Brooklyn in the 90’s, known as “The A-Z.” This was the site for the popular Thursday cocktail hours in which local artists and people from the neighborhood would gather socially and test out your new living systems. Your project in zingmagazine 23 features candid photographs from these congregations, and these photos can be seen affixed to the walls of the apartment. Your work calls into question the usefulness or function of space and day-to-day objects, so I am curious if these photographs, these memories, serve(d) an important purpose in your routine.

I know my work has often been described along the lines of functionalism—but I’m actually not so interested in practical function as I am in psychological function and things like social roles, or value systems. So The A-Z, my Brooklyn rowhouse/storefront functioned as a testing grounds for these experiments—and as a space that allowed my works a kind of autonomy from traditional exhibition spaces. Thinking about various forms, independence or self-sufficiency has always been an important focus—both back in Brooklyn and here at A-Z West in the desert where I have tried to create a center outside of any existing centers.

In trying to create a “center” in Brooklyn we created our weekly cocktail hours, which were basically open to anyone who was willing to attend. I loved the cross sections of people who would find their way through the doors, including other neighbors on the block, fellow artists and curators, critics, gallerists and then the more established artists who made the trek out from Manhattan. Back then Williamsburg was considered totally remote and peripheral to the art world in Manhattan, so I remember being pretty blown away when people like Jerry and Roberta made the trip out.

And the photos were really just a way of cataloging the journey—a sort of sentimentality of sorts. My grandma had photos of her grandkids, and dogs and horses on the wall of her ranch-home. I had photos of my friends and people who made it out to my nook in Brooklyn. As I look back at these images now I think it’s sort of amazing to see my peers and myself in these early years of infancy.

Are there any memories that you are particularly fond of from these gatherings that you’d like to share?

We used to try to think of fun things to do for the cocktail evenings—I remember once Mike Ballou prepared an amazing spread of raw oysters. I can’t quite remember why, but I seem to recall that he did this while wearing boxer shorts. And we found a book of personality tests, so sometimes we would drink cocktails and give each other the quizzes so that we could compare personalities. Also I had a huge 80-pound weimaraner named Jethro who we used to have to muzzle because he would go sort of crazy with all the people around. I’m still really grateful to everyone who tolerated my really annoying dog.

It has been 15 years since you moved to Joshua Tree and began A-Z West. Can you talk about how this endeavor has evolved since its initiation, both for you personally and for the people who have engaged with it? Has anything ever unexpectedly occurred at A-Z West that had a lasting impact on how you view the project conceptually, or how it functionally operates?

Sure—talking about the community at A-Z East, it makes me realize that in a lot of ways A-Z West has actually become very similar, though this wasn’t my intent at all in the beginning. Originally the two projects were related in that they were both meant to be places where I could make prototypes, live with them, and make them public in their original contexts. But the difference between the two was that I really wanted to have more time alone and more removal from the art world out at A-Z West. I’m never bored and rarely lonely. When I first moved to the desert I could go days without seeing anyone. The phone would ring and I would try to answer it, but find that I had lost my voice from not speaking to anyone in several days.

Now at A-Z West I have a full-on studio with a group of people who I work with. We have open season in the Wagon Station Encampment twice a year (our open season actually starts today [April 20]—and throughout the course of the day ten people are going to arrive to spend various amounts of time here) and A-Z West also has a guest house, and two shipping container apartments for people who come to work on projects. So the desert has become a really active community with lots of activity and people coming and going.

Ultimately A-Z West, similar to A-Z East, has become an entire organism that is bigger than myself and bigger than my own life. I think that it’s super interesting when this happens—and at some point I can see it growing into something that may have a life of its own that will allow me to go explore some other new context—maybe starting with something more remote all over again. (Though If I do that—I think I’ll work hard to keep the next project a little more low key!)

It is interesting you say this because your work has this tension between a desire to be communal and social, and a desire for isolation and escape. I think this is a universal dynamic that all people grapple with inn some way. Is this a deliberate pattern, where your time in solitude is like a hibernation period that brings forth new ideas about public/collective life?

It isn’t deliberate, or at least it isn’t something that I thought about and planned to happen—but I feel that you are completely right about this being something that we all struggle with. Trying to find a balance between private and public, individual and collective. But I have noticed that being alone for periods of time helps me to appreciate and value people more. So that is the beneficial part of being able to create distance.

You are currently preparing for a show at the Palm Springs Art Museum Architecture and Design Center, in which you collaborated with the museum’s curators and selected works from the collection to commingle with your “Aggregated Stacks.” According to the information presented on the museum’s website, your focus in on integrating your Stacks with Native American weavings. What was your thought process in selecting from the collection? Will other, perhaps three-dimensional, objects come into play in this exhibition?

The collection actually had a lot of different works that I was interested in—for instance it has really amazing Albert Frey archives that include all of his receipts and bank statements and personal photos! But the work in the exhibition really had to do with the space itself—which is a newly restored Stuart Williams bank building. It’s a really wonderful piece of mid century architecture that is strongly tied to the grid. I knew right away that a body of my own work titled “Aggregated Stacks” would tie in perfectly with the architecture—these works also are based on a grid, but theirs is more of a decomposing grid where everything is a little off kilter.

Then culling through the museum’s collection I was really drawn to the textiles. I used a lot of Native American weavings in the show, and also some mid-century table cloths and a piece that I think may have been a curtain at some point, as well as a contemporary tapestry by Pae White. All of the textiles are arranged in a gridded composition on large pieces of carpet. So the textiles aren’t three dimensional—but displaying them on the floor does alter their reading and in a sense gives them a more spatial quality that I’ve been really interested in lately.

In a recent series of art21 segments, you mention how the lines between art and design are continuously blurred and redrawn and that your aesthetic is constantly changing. How would you describe where you are at right now, aesthetically and along the art/design spectrum?