Rebecca R. Hart is the Vicki and Kent Logan Curator of Modern and Contemporary Art at the Denver Art Museum. Three shows curated by Hart are currently on view in the Hamilton Building of the Denver Art Museum: Shade: Clyfford Still/Mark Bradford on view through July 16, Audacious Contemporary Artists Speak Out through August 6, and Mi Tierra: Contemporary Artists Explore Place through October 2017.

Interview by Rebecca Manning

With a BFA and MFA in Fiber from the Kansas City Art Institute and Cranbrook Academy of Arts, respectively, how did you became interested in pursuing a MA in Contemporary Art History, and eventually curating? How did your career evolve?

My first degree is from Williams College in art history. During my senior year, while writing a thesis on Mughal book illustration, I became curious about all Islamic decorative arts. Soon I found myself working in a Swedish tapestry studio (in the buildings that are now MASS MoCA) by day and writing my thesis at night. It opened a world to me that I hadn’t imagined. I followed my heart and spent twenty years as a fiber artist. All along I supported my studio practice by teaching and lecturing in museums.

When I was at Cranbrook most art academy students returned home in the summer. I had two daughters living with me so I stayed in Detroit. Gerhard Knodel, artist-in-residence for fiber, suggested that I volunteer at the Detroit Institute of Arts. Based on the work I did, the DIA invited me back to work as a curatorial assistant when I graduated. I was at the museum for twenty years, first in the department of twentieth century art, then when the department of contemporary art was formed in 2003 I joined it, and eventually lead it for ten years.

Since starting at the Denver Art Museum in 2015, what have you noticed that is unique about the arts community in Denver?

I’m always discovering new people and practices in Denver, in part because many strong, independent positions are articulated by local artists. There’s a diversity of practice, not a primary locale-centric mode as there was in Detroit. Sadly however, there’s not much attention given to promoting Denver artists in a larger arena. I wish that somehow artists could receive a fellowship, which included professional development and supported studio research; that we had a network to validate and showcase talent broadly.

There has been a great deal of positive response to your current exhibition Mi Tierra: Contemporary Artists Explore Place, which is on view in the Hamilton Building through October 22, 2017. What has been the most rewarding aspect of curating that show?

There was a moment just before the exhibition opened that was exhilarating. Jim and Julie Taylor hosted a dinner at The Vault for the artists, their work crews and galleries. For the eighteen months that we worked on the show, I focused on artists individually or sometimes in pairs if their installation dates or themes overlapped. At the pre-opening party spontaneous kinship formed among the artists, assistants, galleries and extended Denver family. Until then I thought of the artists as individuals and soon learned that together they became a powerful community. The potency of the individual and communal voices is one of the strengths of the exhibition.

I completely agree that the individual and communal voices are one of the many strengths of Mi Tierra. Together, your exhibitions Audacious: Contemporary Artists Speak Out, and Mi Tierra, seem to coexist rather seamlessly. As you move through the third and, then, fourth level of the Hamilton Building, the idea of categorization—groupings of works related to gender, ecologies, and ethnicities—fade away to an extent. Ultimately, the viewer is left with Contemporary art that is charged with socio-political relevancy. From Robert Colescott’s 1988 painting School Days, to Ana Mendieta’s video installation Volcán, 1979, to Jaime Carrejo’s One-Way Mirror, and Ana Teresa Fernández’s Erasure, the work is very topical. How much did you intend for these two exhibitions to converse with one and another when you were considering the experience of visitors going through both exhibitions?

The DAM’s contemporary collection has particular strength in artworks charged with socio-political commentary. This, in part, is the result of the leadership of my predecessors, Dianne Vanderlip and Christoph Heinrich, and also because collectors like Vicki and Kent Logan believe that contemporary art comments on our times. Two years ago, after I accepted the position but before I began working in Denver, I knew that I was curating a long-anticipated exhibition of Latino artists and reinstalling the third floor galleries with a selection from permanent collection. The reinstallation was scheduled first. I wanted to learn about public and institutional tolerance for controversy so I chose “audacious” as the leading theme. Although you mention that categorizations seem to fall away, I would contend that each artist asserts their position informed by their gender, ethnicity and peer group.

While I was working on Audacious, I was reviewing artists for Mi Tierra. Strategically I assembled a group of Latino advisors who helped me reflect on the thematic veracity and political valence that each artist brought to the project. My goal was to present an offering that engaged topical issues and featured artists who I profoundly respected. Many of the artists were under contract before we knew who the presidential candidates were. The present political climate in the United States encouraged some artists to “turn up the volume” in the final installation. However, their commentaries were already embedded in the installations months ago.

For me, the works in both Audacious and Mi Tierra go beyond representation of contemporary socio-political issues, and seem to be actively conversing with current discourse and events. So, in a way, that conversation keeps evolving, and the experience has been different each visit—depending on what I saw on the news that day, or read that day, etc. How did current events impact or at all influence the way in which the exhibitions were carried out after their initial conceptualization? Do current events continue to shape how you think about the exhibitions even now?

When I work on an exhibition I try to write a statement of one or two sentences that distills the theme. Then everything in the exhibition is tied to that idea. I rarely change the theme but sometimes need to adjust how I’m going to address it. Along the way there are conversations with the artists, who sometimes don’t realize how their work functions, which help us both understand the project in different dimensions. Good art resonates through time and echoes across varying situations.

You obviously have a great deal of expertise in your field given your time as a practicing artist, your substantial tenure at The Detroit Institute of Arts, and the prestigious position you now hold as the Denver Art Museum’s Vicki and Kent Logan Curator of Modern and Contemporary Art. What advice would you give to an aspiring curator?

As a curator who works primarily with living artists I see myself as a bridge builder working with an artist’s vision, institutional mandates and the need to communicate with an audience. Whenever I’m working on a project no matter who the artist is—Matthew Barney, Shirin Neshat or local artists like Jaime Carrejo and Dmitri Obergfell—I like to lead with sensitivity to their position and profound respect for their individual creative process. With Matthew, for instance, I sent him books about Detroit life written by popular authors. One scene, that I particularly liked, was realized in River of Fundament. It took only a suggestion to help Barney understand how he might translate the scene in the novel into his narrative but then I needed to let it evolve in his unique language. So to sum this up I might say: build bridges, listen respectfully and deeply, and allow each artist to express themselves in their own way. Authenticity always rings true.

Dmitri Obergfell, Moonwatcher, polystyrene and steel, 2017 Photo: Wes Magyar

Dmitri Obergfell is a multimedia artist from Colorado. He received his BFA from Rocky Mountain College of Art and Design in 2010. Obergfell has exhibited in Denver, Chicago, Los Angeles, Rome, and the Czech Republic. He currently is showing work in both the Denver Art Museum’s Mi Tierra: Contemporary Artists Explore Place, and a solo show at Gildar Gallery, Man is a Bubble, Time is a Place. Obergfell’s solo show continues themes of classicism and considers concepts of time. Man is a Bubble, Time is a Place is on view until May 6 at Gildar Gallery in Denver.

Interview by Rebecca Manning

Initially you studied photography and video art at RMCAD, correct? At what point did you shift into sculptural work? How does your video/photographic background inform your current practice?

I have always made sculpture. Yes, I do have a degree in photography and video art, but the program I attended encouraged exploration. One of the reasons I focused on photo/video is because I could continue my interest in other mediums. I am happy with the basic knowledge of photography I maintain as it has helped me train my eye and hone some software skills, which I use in art fabrication nowadays.

Could you explain the process of fabrication that went into creating your sculpture Moonwatcher?

The fabrication process for Moonwatcher is an important part of the concept. This artwork would be totally different if it were carved out of stone by hand, rather than CNC routed out of polystyrene. Moonwatcher’s Greco-Roman form is used to create a contrast between ideas of the past and contemporary means of production. Moonwatcher’s fabrication process started as a 3D scan from the creative commons of the Internet. I downloaded the 3D form and then augmented it by cutting the limbs and cutting out the negative space in the torso. After I made my changes to the form, the file was sent to a CNC router, who carved it out of polystyrene foam. I am excited to continue with this process because it has a lot of possibilities moving forward. Projects like the Institute for Digital Archaeology are inspiring because they use similar techniques to resurrect artifacts that have been destroyed in places like war-ravaged Palmyra.

Moonwatcher has an ancient symbol cut out of its torso, the Triple Moon, and like the figure it is cut out of, it rather instantaneously signifies to the viewer that it is something ancient. To my knowledge, that symbol is associated with pagan goddesses. Embedded in a sculptural body that basically encapsulates the male ideal form, I can’t help but think that you are getting at some sort of ideal gender binary within your sculpture. Was this at all intended? Most of your sculptural work that I have seen contains male figures. Do you consider gender at all in your work?

No that wasn’t my intention, but I see how it might be read that way. It’s an interesting interpretation and question, but I can’t say that gender is my first consideration. I have picked figures based on gesture more than gender. Keeping that in mind, there is probably to be said about how women and men are represented in antiquity. I would be remiss to pretend to know what that is, but it would be interesting to research it more.

Not just in your current solo show, but in general, your work seems to link different important movements or imagery in art to present day, making them, in a sense, relevant once more. You are engaging with Greco-Roman art and its pervasive aesthetic, and subverting—at times—expectations and meaning that such an aesthetic inherently carries. Because of the process in which you fabricate your work, you are also dealing with the modern concept of the readymade. How do you go about reconciling concepts and imagery that seem inherently at odds?

I don’t believe the imagery and concepts are at odds. The history of Greco-Roman sculpture extends to mass reproductions being made today. I use the Greco-Roman forms in a present-day sense, they are devoid of their original color and are often displayed with limbs missing. These reproductions present themselves as ontologically charged ready-mades, which simultaneously reinforces the Greco-Roman aesthetic and erodes its original meaning.

I enjoy the way you employ ancient statuary. In your exhibition at Gildar Gallery, I felt almost as if the classical aesthetic of ancient sculpture is for you so reproduced and ubiquitous that it has become a recognizable object or sign. You use other ancient and contemporary symbols throughout the show, most of which are part of works that are coated with chameleon automotive paint. What are you trying to accomplish by embedding these different symbols into one piece of art? Are you trying to build on the associations and meaning that they carry, or are you trying to render them meaningless?

I am reflecting on the the symbols’ similarities despite the different times they were created in. I like to speculate on symbols from this period that might carry the same resonance as those from ancient times. Symbols like corporate logos and emojis may become our society’s version of hieroglyphs due to their wide-ranging distribution in commercial, cultural and social settings. One symbol that interests me in particular is the hashtag, because it has been around since people were drawing on cave walls in ancient Europe. The hashtag is one of 32 symbols that were found throughout ancient caves all over the continent. Today the hashtag is one of the most prolific symbols of our time because of its significance and function in social media. It is fascinating that the hashtag transitioned from a basic form of communication in ancient caves to one of the most prevalent technological symbols. It’s hard to say what the original meaning of the hashtag was, but this form has endured time and adopted new meaning over the course of human history. It is not hard to see how contemporary symbols like the Nike swoosh might carry the same potential.

Dmitri Obergfell, Crushing Beers, chameleon auto paint and urethane plastic, 2017, Photo: Wes Magyar

When I teach an introductory art history course I typically assign David Macaulay’s satirical children’s book, the Motel of the Mysteries, in the first week. The book is set in the future and serves as a cautionary tale to students of art history/archeology about how easily one can misinterpret objects of material culture from the past when they are removed from their original context. In the book, mundane and humorous objects are misinterpreted as objects of veneration . . . I couldn’t help but think of that text as we were walking around the space at Gildar Gallery. Among the intrinsically monumental figurative statue, and sculpted mantel, are aluminum cans which you’ve coated with chameleon automotive paint. In consideration of the dazzling surface material you’ve given these objects, and their purposeful placement in close proximity to a classical-looking sculpture, it seems like you’ve set out to give these cans an intentional significance that they don’t typically possess. Am I onto something there? Can you tell me about your intention in placing these cans throughout the gallery?

I am interested in the commonality of aluminum cans and the fact that approximately a half million cans are used a day. This level of production and consumption reminds me of Monte Testaccio. Monte Testaccio was a garbage dump for olive oil vessels that was used for 250 years during the Roman empire. It is a testament to the consumption of olive oil during that period. It is estimated to contain the remains of 50 million vessels. Monte Testaccio is so large that on the surface it now looks like a large hill in the Roman landscape, rising to 115 feet tall. At the current rate of production, it would only take 100 days to create the same amount of aluminum cans. By comparison, aluminum cans might have a similar effect in creating a legacy like Monte Testaccio, scattering future artifacts of our societal consumption across the planet.

When we were walking through the gallery you were talking about concepts of “deep time,” or an allusion to “victory over time,” and the title of your show deals with time, too. The title Man is a Bubble, Time is a Place, to me, evokes the idea of Vanitas and memento mori—symbolic art that serves to remind man of his own mortality. With consideration of concepts of time and mortality, I felt that your use of materials here was particularly savvy in that Styrofoam, or aluminum cans, are inherently disposable consumer materials—we discard everyday objects comprised of aluminum or Styrofoam without a thought. And yet, those objects, particularly those made of Styrofoam will never break down, and are in a sense going to outlive all whom dispose of them. In a way, this material culture, what is basically considered trash, is what will be left of our existence to posterity. Thus, your work gets at this idea of “victory over time” through use of materials as much as it does in the appropriation of a hegemonic classical aesthetic. Are you trying to make any overtly political or poignant statement through the pairing of imagery from antique sculpture with a contemporary material of a mass-produced nature? Is the juxtaposition meant to make the viewer ponder the significance of their own contribution to the infinitely sprawling expanse of history and time?

Political or poignant, I don’t know. For me this exhibition is a way to process the information I have consumed. A lot of that info is about long time arcs and eternity. I have been studying both versions of 2001: Space Odyssey, Timothy Morton’s Hyperobjects, Matthew Arnold’s poem The Future, Karel Dujardin’s painting from 1663 Boy Blowing Soap Bubbles, and theories like Time Dilation. One passage I found particularly moving is from Arthur C. Clarke’s version of 2001: Space Odyssey,

“And somewhere in the shadowy centuries that had gone before they had invented the most essential tool of all, though it could be neither seen nor touched. They had learned to speak, and so had won their first great victory over Time. Now the knowledge of one generation could be handed on to the next, so that each age could profit from those that had gone before.”

The artwork is a more of a manifestation of my thinking process than a prescription for others. I see it as a presentation of information that the viewer can decipher how they see fit. The work in the exhibition isn’t encouraging people to recycle more or drive a Prius, but simply consider existence over a relatively long period of time.

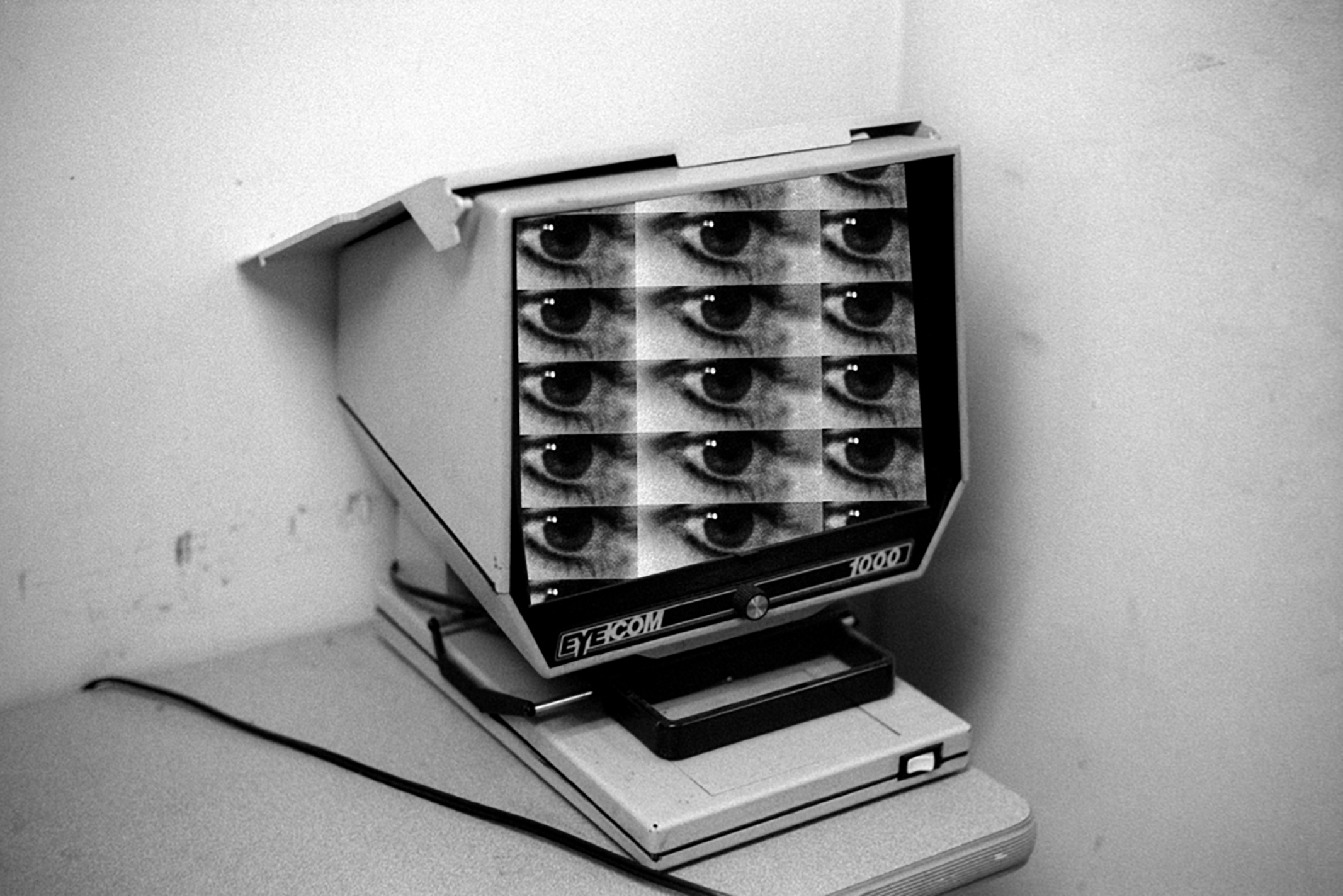

Maria Antelman, Eyecom, 2016, courtesy of Melanie Flood Projects

Maria Antelman works in photography, video, and sculpture, often through the lens of technology. Her latest exhibition, “My Touch, Your Command, Your Touch, My Command” opened at Melanie Flood Projects in Portland, Oregon on January 27th and is on view through February 25th. The work, a series of collages and a video, investigates human dependencies on informational tools and how these tools in turn shape their users. This exhibition is the fifth installment of an ongoing series at Melanie Flood Projects called Thinking Through Photography, which includes a comprehensive survey of contemporary photographic practices through programming that highlights experimental and diverse approaches to image-making.

Interview by Brandon Johnson

Let’s start with the title of the show: “My Touch, Your Command, Your Touch, My Command.” There’s a clear implication of control—losing control, but also being in control. The word touch implies something sensual, almost sexual. There’s a power dynamic that flows between two sources. Am I on the right track here?

In an uncanny manner, “touch”—sensual, sexual, personal, etc—turned into a technical gesture: I-touch. We touch screens all day. There are cuddling parties where one can experience the warmth of the human touch. Perhaps a new invention can be warm, soft screens at 98.6 °F, the temperature of the body. The collages in the exhibition show hands touching microfilms, the predecessors of big data. There was a time when one could physically touch information. In digital haptics every touch is a decision which releases a code which itself becomes a command. I am thinking of the hand as a tool. The thumb and the grip were related to the industrial revolution in handling machines. The index finger is the protagonist in this revolution. In the movie E.T., the extraterrestrial has an elongated index finger. The point of the index finger lightens up when E.T. feels a connection. The title of the show refers to emotional relations of interdependence with information and network systems.

Why use the dated technological form of microfilms in your collages? Is this related to being physically closer to information?

I was trained as an historian, to read the present and to think about the future through the lens of the past. Mechanical apparatuses are connected to our lineal thinking—one could make sense of how a machine functions. Digital devices surpass logical thinking; they are black boxes—one cannot understand how they work. I still use analogue film cameras because I need the slow processing time in a medium that is constantly advancing technologically. Microfilm technology is based on photographic memory, light and magnifying optics. In this body of work, these apparatuses are used literally and metaphorically to bring together the analogue past with the digital present.

There’s an element of Orwellian dystopianism to these works—like a scene from a David Lynch film where someone is watching themselves through a CCTV or is trapped within a monitor. Is there something inherently negative about our experiences with digital technology? And conversely, is there anything that redeems this?

You mean Videodrome by David Cronenberg which is indeed very tech noir. Communicating translates as the act of being social but in a digital format it has this transformative power, one that possesses people. There are so many platforms and choices: reviews, comments, likes, dislikes, loves, hates, faces and cute sounds. There is no silent time, time has turned into information, and information is data, and data is the new economy. I love my digital experience, it is super sexy and fun, and feels fresh, and we are all connected, and its participatory, and sharing moments can feel so good: it’s a validation. Perhaps there was a dormant part in my brain waiting to be filled with all this information and now this part is hungry: it needs to be constantly logged in, updated, saved, downloaded, etc. We are becoming automated: codes predict and cover all our needs and desires, and we never get lost, don’t close our eyes, rarely let go. It is a very interesting self-discovery. I like it (thumbs up emoji, happy face emoji).

I had Lynch’s Inland Empire in mind, but Videodrome works even better. There are some episodes of Black Mirror that also relate closely. Interesting that you speak of a dormant part of the brain being hungry and developing an appetite for information. I’ve always liked to think about how technology and communication fit within the grand scheme of evolution. How human language, tools, and abstract thinking allowed us to dominate the other species on the planet. It seems that technology has developed at a faster rate than our bodies (and brains) can adapt. The sheer amount of information is impossible to fully process and retain, in part due to the lack of idle time where reflection typically takes place—when we close our eyes and let go. Are reflection and imagination the antidotes to technology’s distraction? Or is this something that technology merely deprives us of? Are there aspects of technology that we need to resist?

I think the antidote to technology’s distraction is boredom. Sheer, old-fashioned, torturing boredom. Maybe we need to remember what it feels like to be bored. Then new habits may kick in. The problem is that the overload of information is getting boring as well. But while it’s constant input becomes repetitive, social media responses still release dopamine in our brain every time we get a FB like or even better a FB love. Now information needs to evolve, so our brains, hungry and addicted to their dopamine doses, will continue to stay engaged. Otherwise, we may turn into ADD zombies looking for exciting content to suck into. Nerve is a great teenager thriller. The story is about an online “truth or dare” game with players and watchers. The code of the game knows everything about the players from their social media and consumer profiles and uses this knowledge to challenge them in extreme, personally tailored situations. The more dares, the more likes and the more money gets transferred instantly in your bank account. Digital natives live in a different world. Most young entrepreneurialism is about some digital service: an app that replaces some gesture, some decision, some desire. Perhaps, it is all about mediating and facilitating experiences. Same as wellbeing, another new industry or the economy of wellbeing. I was reading the other day about this hi-tech, luxury meditation center somewhere in the Flatiron. A short meditation session leading to a nap (all in 20min), costs $18. It takes place inside a perfectly lighted dome room, with perfect sounds, blankets and pillows. It is a place where you don’t have to put any effort in meditating, instead you walk into a meditative environment equipped with the right props and boom, you think you are meditating. It is problematic. I think digital culture is picking up so easily because people understand technical skills better than experiences.

Getting back to the work itself for a minute. The Spacesaver works are collages, yet a viewer wouldn’t necessarily know it (especially when viewed on a screen)—they’re very seamless. Can you talk about your process in making this series? And since the show is part of an ongoing artist series at Melanie Flood Projects called Thinking Through Photography how the work engages with photography as medium?

When I got interested in microfilms, I visited a lab where they convert bulks of paper information into microfilms, from architectural drawings to checks and invoices. I ran some tests shooting with their duplicator cameras, with my hands in the shot handling paper. Then, I took those images, in microfilm format, and looked at them through the reader apparatus. It was very confusing and disorienting: the real and its representation were slipping into each other. I tried to capture this effect in my collages: a circle of motion from inside out and in reverse. I was thinking of screens opening to more screens, like a maze where you find yourself in every screen. Media is very narcissistic. Then, I started looking at technical, user manual and marketing images of apparatuses from the 60s. A female model poses with the device, touching it in a very soft machine-erotica style. The title of Melanie’s series Thinking Through Photography is very appropriate: images are the new communication form. Alexander, my son the other day explained one of his thoughts: numbers are infinite and combinations of language are infinite, so one day numbers will replace words. I will ask him whether images will one day replace numbers. Machines already speak images.

Working within a wide range of media including sculpture, installation, and performance, Connie Walsh uses her work to explore the transitional space between interior and exterior, intimacy and detachment, private and public, self and other. Currently working in Los Angeles, her work has been presented in numerous exhibitions throughout the country, including solo shows at Marianne Boesky Gallery and SculptureCenter in New York. In zing #24, Walsh presents the project “interior façade,” a series of photographic pairings of interior architectural details with amorphous sculptures made of rug-hooked canvas, beeswax, and yarn. Visually intricate and immersive, Walsh’s project provides an expansive inquiry into both the divisions and inextricable connections between places of interiority and exteriority.

Interview by Emma Cohen

Many of your works are sculptural, or created for installation. What was it like to create a sculptural work that would be presented in the two-dimensional format of a magazine? Is something lost, or added, when the work is photographed?

I am interested in the expansion and potential collapsing of illusionistic space when using different dimensions within a piece. The project consists of both the sculptures and large-scale digital prints. The photographs are a further investigation accessing the interiors of the three dimensional space of the sculptures. This space is then manipulated and flattened and finally juxtaposed with a detailed exploration of architecture, which offers structure for the biomorphic sculptural forms. The magazine format reinforced this pairing with a central seam. I became interested in this place of contact, both in how these differing spaces inform each other as well as with how they create visual tension with their proximity. The large format prints are the same ratio as the magazine with two images making up one print with a central transitional vertical line.

I really appreciate the freedom that comes out of Devon’s approach to magazine proposals being as projects—i.e., that she offers a span of pages in the magazine to do with it what you will. It allowed me to think of those pages as a three-dimensional space to work within. I was interested in the images being “read” horizontally and vertically with a centerfold. In the magazine, the thickness of the spine blurs the transitional space between the two images implicating the possibility of actual space.

Did you think about the readers of the magazine and the physical ways in which they would interact with the piece when you were creating your project?

Yes. The images are all full-bleeds and the layout varies within the pages of the project. I set up a spatial sequencing of an image of the sculptures with an image of the architectural details each on its own page and at times I interrupt that with one image taking up two pages entirely—these being images of the sculptures—a centerfold. This encourages the viewer to turn the magazine while looking at the project and maybe even disorienting the space of the subject and his/her relationship to the object of observation. I was interested in shifting the viewer’s positioning and his/her ability to distinguish between the space of the interior and its relation to the exterior being outlined.

You mentioned the relationship of interior/exterior in this piece, and in reference to other works you have written about investigating the relationships between self/other and individual/society. Did you learn anything about these relationships when working on interior façade? How has your understanding of or attitude towards these dichotomies developed throughout your career?

In past projects I’ve combined personal events or moments with environments that suggest and heighten the place of contact, or transaction, between private and public experience. In this project I was more interested in the ambiguity of these realms—as being oppositional and in exploring the transitional space between interior and exterior, intimacy and detachment. This suspended space is both permeable and of a shifting nature. The existence of a “skin-like” interruption of contiguity un-sites the viewer’s conventional perspective.

How do you see the opposing pages of “interior façade” interacting with one another?

As I was creating the piece, the idea of sculptural spheres—a metaphor for what was once inside and extracted—led to a tactile inquiry into a possible interior. I created these sculptures around balls of varying sizes, but eventually the spherical forms started to collapse due to the weight of the rug hooked yarn and leave more misshapen inaccessible spaces. I then had to go within the sculptures to take some of the photographs.

As for the architectural spaces, I am currently living in a Schindler apartment. Schindler’s proportions, fluidity of space, and continuity between inside and outside are framing my family and our domesticated movements. Images of the architectural details provide structure to the images of the biomorphic sculptural forms. Photographic pairings of the sculptures with chosen interior architectural details initiates the perceptual sense that exterior is defined by the interior and vice versa.

Do you have any current interests or projects that you’ve been working on that you can share?

Lately I’ve been interested in memory—how selective it is and seemingly private yet it functions within a larger context. I like the idea of selective memory. I have also been thinking about a further transformation of the sculptures in the project interior façade. I’m exploring the possibility of casting the sculptures out of silver or aluminum and having it be a one off burnt out process- losing the sculptures completely—the color and tactile material—into a more permanent weighted mass. In a sense giving the empty interior cavity a solid form.

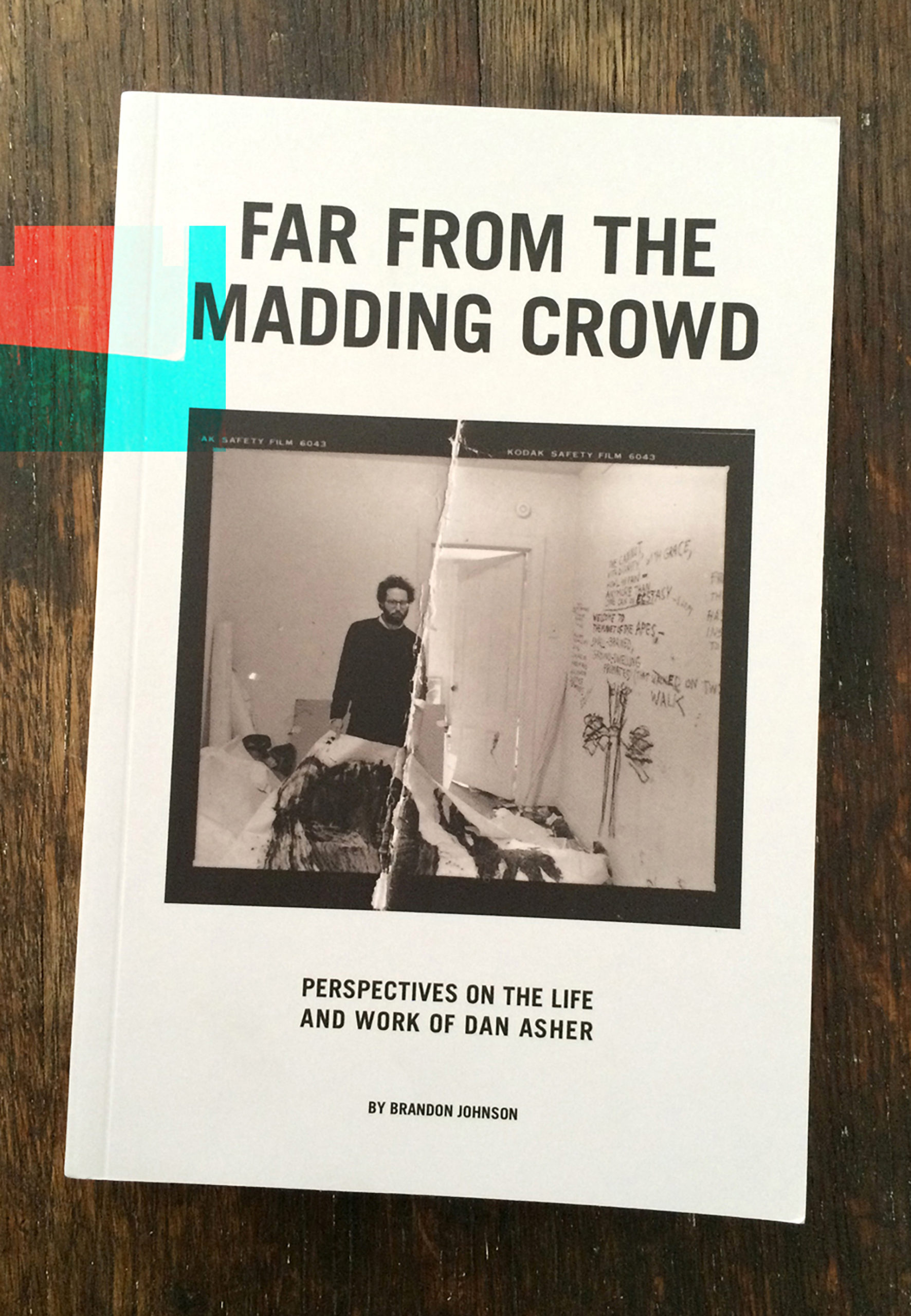

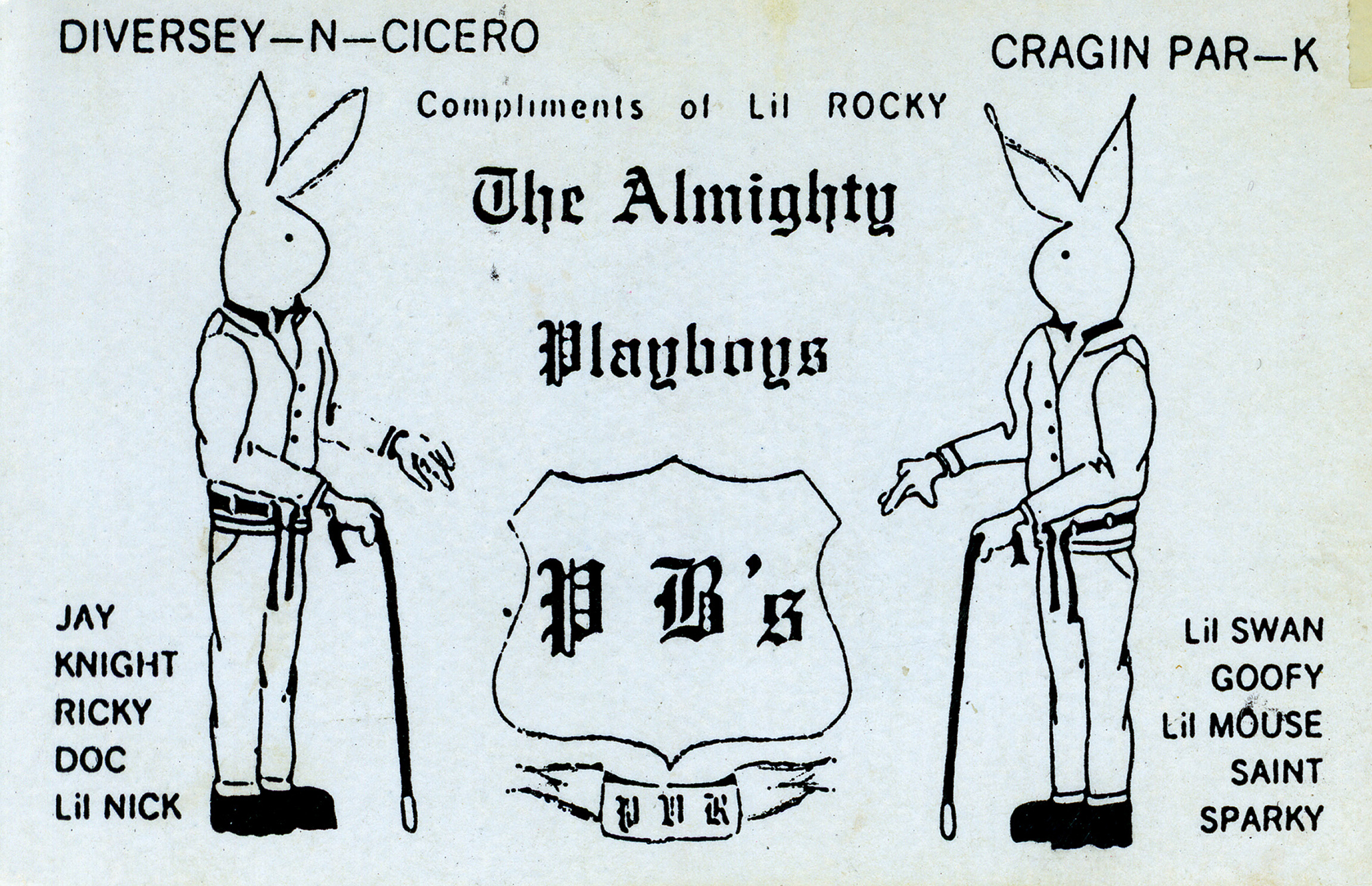

Upon arrival in New York in 2006 to attend The New School, Brandon Johnson also began an internship at zingmagazine. Flash forward a decade later, and we find him as Managing Editor of this curatorial publication. From promoting zing at book fairs in New York, Baltimore and Los Angeles, to a residency at SOMA in Mexico City earlier this year, Johnson has been developing a report with the contemporary art world at large. One individual in this community, artist Dan Asher, left a lasting impression on Johnson before his untimely death in 2010. Asher is the subject of Johnson’s book, Far From the Madding Crowd: Perspectives on the Life and Work of Dan Asher, published in Fall 2015 as part of the zingmagazine issue 24 special edition. Comprised of interviews with various figures from Dan Asher’s life, this book offers readers an unprecedented and intimate look at this talented yet often misunderstood artist. Also featured in issue 24 is the poster-sized reproduction of a 1970s era Chicago gang compliment card, one of many from Johnson’s personal collection. These zingmagazine projects scratch the surface for what will be continuous engagements with these unique areas of research and interest.

Interview by Hayley Richardson

You have two projects in issue #24: a poster titled “The Almighty Playboys” and a book, Far From the Madding Crowd: Perspectives on the Life and Work of Dan Asher. Can you give a little overview into what each project is about?

Sure! The book project, Far From the Madding Crowd: Perspectives on the Life and Work of Dan Asher, is just that: a series of interviews I conducted with people who knew the late artist Dan Asher in various capacities: art dealers, other artists, friends, and even his dentist—about forty individuals in all. Dan Asher was a prolific artist and fascinating individual, and the interviews reflect this. The text is interspersed with images I chose of Dan and his work as visual reference. The poster project “The Almighty Playboys” is an enlargement of a Chicago “compliment card” made by the street gang the Almighty Playboys in the 1970s. I own a collection of these cards, and between the weird illustrations and writing on the back, thought this one was particularly interesting on a visual level.

Are there any interviews that stood out to you as being particularly revelatory? Did you learn anything new about Dan that you feel changed or enhanced your perspective of him?

I learned something new from each of the interviews and each molded my perspective in a different way. It was an investigative process for me. Prior to making this book I didn’t feel like Dan’s closest friend or an authority on his artwork by any means. But I wanted to know more. So I followed the leads, and each interview added to the bigger picture, or should I say portrait? With that said, Atom Cianfarani & Maya Suess’s interview had a lot of specific information and anecdotes that weren’t really discussed otherwise. It seems like Dan opened up to them quite a bit about his personal history. Their interview added an emotional depth while managing to fill in some missing pieces of the narrative.

In 2014 you co-curated an exhibition of Dan’s work at Gildar Gallery in Denver, and now with the book it is very apparent you have a vested interest in this artist. What drew you to Dan’s life and work initially? Do you have plans to work on other Dan Asher-related projects in the future?

Being a wet-behind-the-ears 21-year-old arriving in New York, Dan embodied for me this romantic view of a downtown artist—bohemian and cantankerous, a holdover from another era. Being fond of Devon, zingmagazine, and the energy of young people, Dan just made himself present in my life. But as I began to discover his work via the pages of zingmagazine and galleries of the Dikeou Collection, my fascination grew. The work seemed so personal and had great appeal to me on an aesthetic level. Often, it attempted to capture these fleeting moments of poetic poignance. A stillness within flux. I became an advocate of his work and I am currently exploring more opportunities to do so in the future. The filmmaker Tom Jarmusch and I are currently developing program of Dan’s videos for a screening. I’m also talking to Martos Gallery, who represents the Dan Asher Estate, about organizing a discussion at the gallery during Dan’s forthcoming solo exhibition next year. Fingers crossed all works out.

Tell me more about the “compliment cards.” In your curator statement you share that you discovered one of these in some of your dad’s old stuff in the attic and learned that they are specific to the Chicagoland area from the 1970s and ‘80s. How were they used and what more have you learned about them since your discovery?

Yeah, I found that first one in a cigar box in our attic. Apparently my Dad’s friend from high school was a member of the Royal Capris. It’s been tough to find many reliable resources for information on compliment cards, but from what I’ve deciphered the cards were were made mainly to display pride of the gang, disrespect towards its enemies, and for recruitment. Other uses include passing them to friends or associates, “We’re throwing a party tonight at so-and-so bar. Show this card at the door.” As far as their origins, I’ve noticed that motorcycle gangs from the ’50s and ‘60s such the Hell’s Angels and Straight Satans made calling cards. For example, a biker would see a car pulled over, give them mechanical assistance, and pass them a card saying “Serviced by the Hell’s Angels”. Some of the street gangs in Chicago find their roots in greaser gangs from this era, using biker traditions and aesthetic as models. My theory is that this is where the idea for Chicago compliment cards came from, and proceeded to gain popularity among white and Latino gangs on the Northside, Westside, and near Southside of Chicago. What’s great about these cards is that they’d change hands over the course of their existence, with handwritten messages, symbols, and names accruing on the backs. With a little knowledge you can learn to read this information. Many of the O.G.s have amassed sizable collections, and will attend get-togethers with other former members where they trade original cards and sweaters. Old enemies recount their younger lives over beers. Funny how that works.

You should try to track down the O.G.s and meet them for a beer! Where have you been sourcing the cards for your collection?

One of my sources is a former member of the Almighty Gaylords, which was the biggest white gang in Chicago during the era. He built a collection of cards during his time as a member and beyond. Now lives in the Western suburbs I believe and has decided to sell off his collection. I cherry-picked a few cards off him, then ended up buying out most of the rest of his stock. My other source is a USPS mail carrier for the city of Chicago. He has a few different types of collections, including original cassette tape mixes of Chicago house music from the ‘80s and ‘90s. Apparently, he was a DJ back in the day. Told me that he came across an album of compliment cards and was selling them off. But also sounds like he had connections with former members, or played the middle man in certain ways for a friend. Didn’t really get his clarified. But a nice enough guy. Acquired some rarer examples from him, mostly Latino gangs—the Party People, Latin Kings, Night Crew, Spanish Lovers, and King Cobras, among others.

I think they’re fascinating relics of distinct time, place, and culture and would be appealing to a wide demographic. Any ideas for what you might do with the collection in the future?

I agree! Everybody I show them to or tell about thinks they’re pretty groovy. I mostly like them because of their specificity to Chicago, ad-hoc aesthetics, and origin in an era before my time. Although I’m a bit conflicted on any glorification of gangs in light of the gang-related violence that occurs in Chicago to this day. This is a huge, complicated problem, and is related to greater dynamics at work in our country. But I suppose this is the case with any outlaw culture – the romanticized image versus the unsavory reality. With this in mind, I’m hoping to do a release event for the book & mini-exhibition of the collection in New York this Fall, then see where else I’d be able to do something similar in other cities, whether as one-off events or as part of art book fairs, etc. Nothing set in stone yet. Going to wait until I have a delivery date for the books and then plan from there.