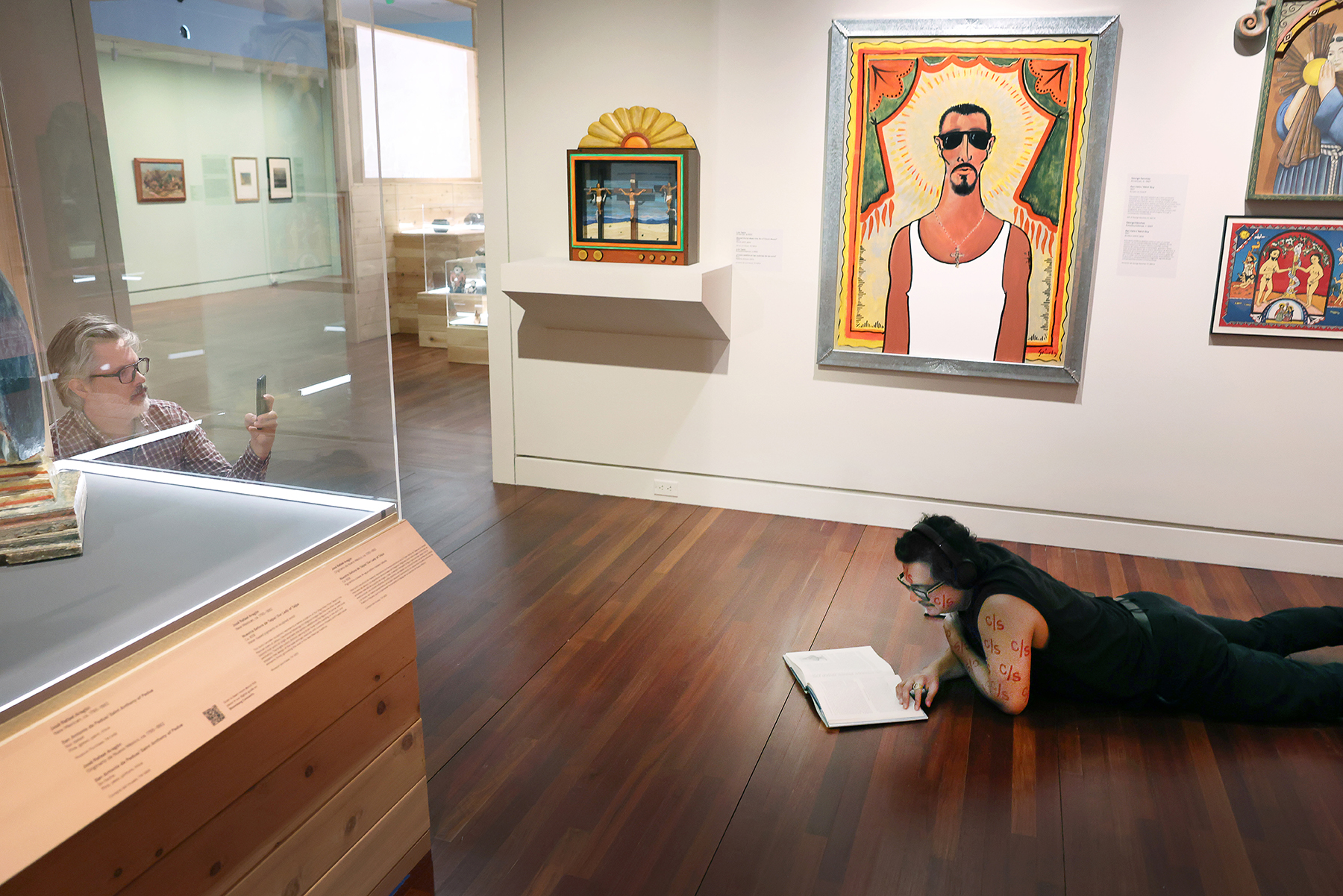

Josh T. Franco, Scriptorium con safos: Gathering Place, 2025, performance at Colorado Springs Fine Arts Center. Photo by Jamie Cotten / Colorado College

Josh T. Franco is an artist and art historian currently based in Hyattsville, Maryland. His dualistic practice, studio and scholarly, originates from his creative roots in West Texas, where he grew up surrounded by the intuitive and ever-evolving art environments constructed in his grandfather’s yard. For Josh, his lifelong immersion within the culture, history, objects, materials, sound, movement, space, and audience of the creative world coalesce into his ongoing “Scriptorium con safos” project, which he most recently performed at Colorado Springs Fine Arts Center at Colorado College. Witnessing the performance myself and chatting with Josh reminded me that immersion in this world is a choreographed balance of solitude and community . . . sometimes formidable but oh so blissful.

Josh T. Franco as Interviewed by Hayley Richardson

You are an artist whose “primary medium is the discipline of art history itself,” and a working art historian. I have to ask the “chicken or the egg” question . . . did your art practice grow from your scholarly pursuits or vice versa, or did they develop in tandem?

For many years, the narrative I held was that my AP art history course in high school was my awakening to the field. That is still in many ways true in terms of disciplinary training. However, after my grandfather passed away in 2015, there was a shift. He was a prolific yard artist, and I grew up among his creations in this constantly evolving hand-built environment. My brothers, cousins and I grew up watching and emulating him. This involved a lot of imagination and working with found objects and devised tools. I have been a maker of imagery, sculptural objects, spatial interventions, etc. since childhood. I was also a big reader from a young age. So now I say the art and scholarly pursuits really were always happening in tandem. It’s also important to note that my dissertation was a 2-year studio-based project involving a lot of collaborative research with fellow artists Joshua Saunders and Alison Kuo culminating in a large-scale installation and performance work in 2011. It was only after the show that I realized the subject of that work–the town of Marfa, Texas–would also be my dissertation subject. So the studio and the scholarly are inseparable for me. The book from the dissertation includes the related artworks and will be out in Fall 2026 from Duke University Press.

Your work “Scriptorium con safos,” which is a sculptural installation which can be activated as a performance, is the perfect embodiment of utilizing art history as medium. It has numerous elements at play with exhibitions and research at its core, as well as expressions of joy and enlightenment. Can you tell me about how you originally conceptualized this ongoing project?

The first Scriptorium came out of a very specific experience. As an art history PhD student, I proposed to teach a class on Chicano art in the department. The department–really just one faculty member among an otherwise wonderful supportive group–refused to cross-list it. I ended up teaching the class, but as a Latino studies course. No student received art history credit for it. I knew of the many historical instances of the discipline and museums rejecting Chicano art as unworthy of study, but it was wild to experience it directly in the 2010’s. I never forgot. In 2017, shortly after completing the doctorate, I received an invitation to be a visiting artist in the art and art history department at DePauw University. I am grateful for the opportunity and the timing; the invitation came when I was clearly ready to digest that experience, which meant making art from it.

My dissertation topic was directly tied to the Chicano art course I had proposed, as it works to understand the relationships between art by Mexican and Mexican-American Marfans with deep historical roots in West Texas, and the steady influx of people interested in so-called contemporary and Minimalist art that has occurred in the past 50-ish years. That first Scriptorium responded to a need for space in which I am not subject to disciplinary (or departmental) conventions or judgments. Thus the books on the ground mark out a spatial territory. The crystals emphasize groundedness, while also serving a practical purpose as bookweights. The “C/S” mark on my body and elsewhere in the work acts as a symbolic boundary. It stands for the phrase “con safos,” a Chicano term that signals solidarity, protection, and completion of a work of art. It typically appears abbreviated as “C/S” in paintings, murals, personal correspondence and a broad range of Chicano visual culture.

Books in the first scriptorium were arranged in a double arc; the inner row comprised books on Chicano art, while the outer ring included books on Minimalism. However, throughout the performance, they get mixed up. My promiscuity is the antidote to the rigid, possibly bigoted attitude that kept my Chicano art class from being listed in the art history department’s offerings.

I called the work Scriptorium con safos: Prologue, because I realized while making it that it could be useful for other topics, which it has been. Also, it’s an addictive work, at least for me. I think about it as being alone in my room, headphones on, doing what I do often in solitude, but as a performance in public. I crave opportunities to do it over and over.

I had the pleasure to witness this performance in action at Colorado Springs Fine Arts Center, predominantly within the exhibition “Gathering Place: Permanent Collection Reinstallation” which you had a hand in co-curating. How does the act of curating an exhibition compare & contrast with developing your own artistic response within it?

Gathering Place was such a dream experience. I do not consider myself a curator, but since 2020 I have been fortunate to receive a handful of invitations to guest curate in some amazing projects and institutions, the FAC among them. As an artist, I’ve taken these as opportunities to make new work that couldn’t happen without the collaboration of great institutions and teams.

In Colorado Springs, a new Scriptorium made sense. The project there is a fundamental re-imagining of the permanent collection installation following years of thinking with a 7-member curatorial team and FAC staff. It’s the result of a lot of deep study, which is what Scriptorium enables. Books were placed across the three wide thresholds of the galleries we had collectively curated. While the bibliography for each performance is planned, I never plan ahead which passages I am going to study and transcribe. In the moment, I realized I could also treat the wall text as another source, so that’s where I started. As I read my transcription of our exhibition statement, I unexpectedly choked up. It was the culmination of a really special collaboration that we were now offering to the world. I stopped myself crying that time, but I think in the future I’ll just let it happen.

These recent curatorial experiences have shown me that curating is a kind of making too. The difference between it and how I work in my studio is that there are a lot of people involved at every step. And now I have a whole body of work that is inseparable from institutions which is so interesting. For instance, Syracuse University Art Museum acquired Scriptorium con safos: Syracuse following a year-long installation. Writing out the paperwork for that pushed me to realize, in practical terms, how a work can exist within an institution as both a collection and a collaborator without my direct involvement.

Josh T. Franco, Scriptorium con safos: Gathering Place, 2025, performance at Colorado Springs Fine Arts Center. Photo by Jamie Cotten / Colorado College

You’ve performed “Scriptorium con safos” five times. Each iteration employs components like movement (and rest), art historical texts, earth minerals, music, writing, and recitation that change with each exhibition and performance activation. What were some of the featured texts for the Colorado Springs performance? Playlist and mineral selections? How are these decisions made?

Some tracks from the playlist (again, what I might be listening to just hanging out alone in my room studying art through books):

Fog – The Ophelias

These Days – Foo Fighters

Standard Lines – Dashboard Confessional

Sympathy is a Knife – Charli xcx

Waiting – Alice Boman

Treehouse – kelseydog

Deceptacon – Le Tigre

Meet Me At Our Spot – The Anxiety, Willow & Tyler Cole

Man of the Year – Lorde

What Was That – Lorde

Drain You – Nirvana

Flash in the Pan – Jane Remover

Straight, No Chaser – Bush

Pinch and Roll – Hum

Age of Consent – New Order

I Fall Apart – Post Malone

Binz – Solange

Casual – Chappell Roan

The books are chosen with much more intention than the music. FAC already includes books related to the exhibition in the entry hallway. We, the co-curators, had contributed to the list months prior, suggesting books related to the works and frameworks of our respective galleries. So for this Scriptorium, the books were already present. It was fun to perform selecting and removing them from the shelves to the floor as audience members looked on. Some of the bibliography for Gathering Place, which anyone who visits the show can peruse, can be reviewed here

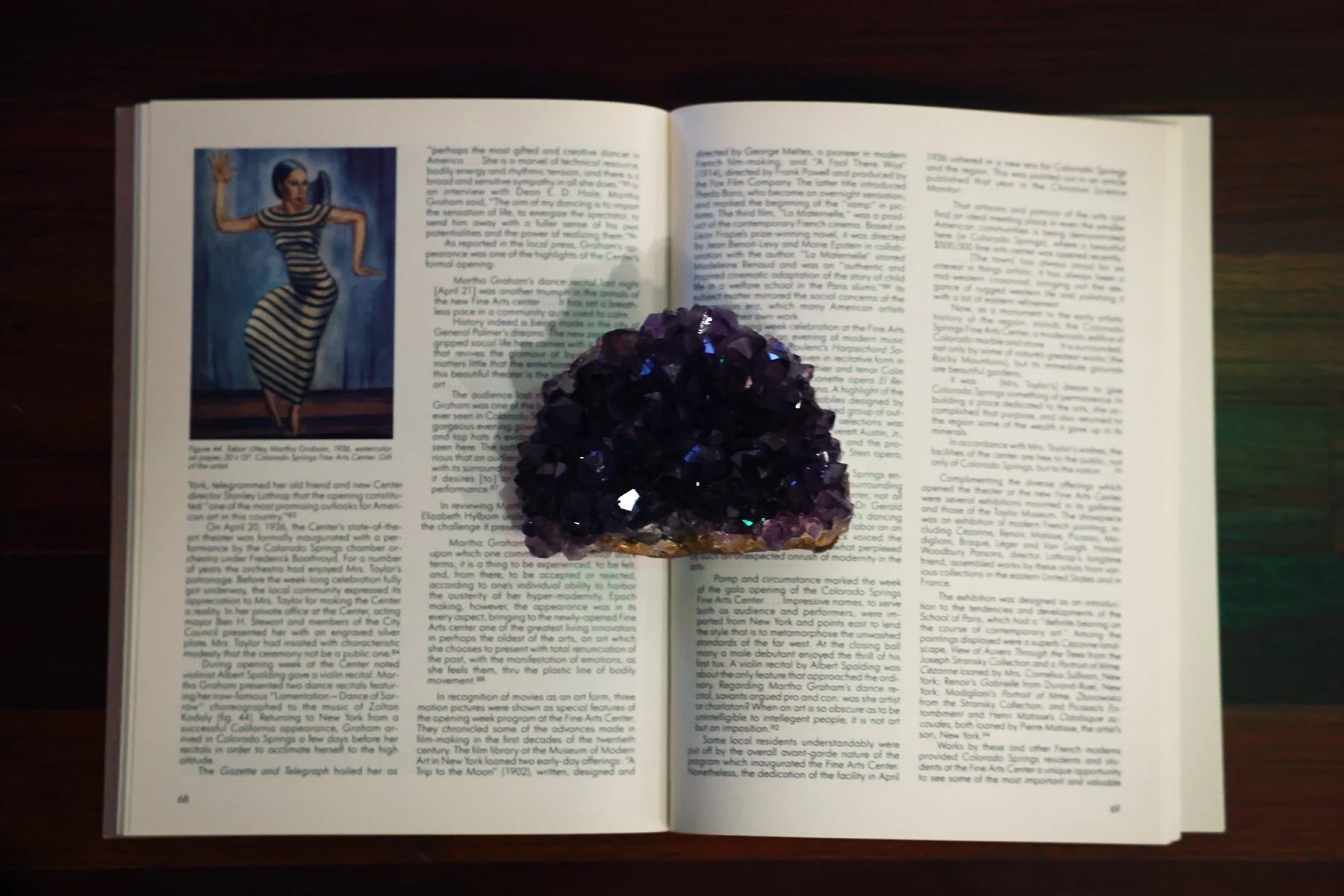

I’m so glad you asked about the crystals, because Colorado opened the work up to colors in a new way. In the past, I’ve used a mix of palm-sized clear quartz chunks and selenite bars because they are readily available, relatively low-cost and, primarily, don’t command much visual attention as they are white and clear. ForGathering Place however, we had the budget and interest to elevate these choices a bit. It was also a fun outing for myself and FAC curator Katja Rivera who researched shops in the Colorado Springs area ahead of my trip for the performance. We drove around town and I think it was the third shop where we encountered the celestite and amethyst I ended up using. That pale translucent blue and the deep purple, respectively, are so seductive and play well with the dark wood floor and low lighting in those galleries. Shifting to these strong colors was significant for me as the artist and Katja as the curator, though the audience may not be aware how so.

What role does the audience play in your performance?

The audience has choices; they can be witnesses, fellow activators, or something else they imagine. Scriptorium is a non-narrative ambient performance. Like the weather, it’s there regardless. How you respond to it is up to you.

When I work with institutions, I ask that there be no announcements or signage. Nor is there a timed score or pre-planned sequence. If you catch me reading a transcription aloud; if you catch me dancing; if you catch me laying on the ground reading; this is all up to chance and the length of time you’re willing to stick around. Additionally, nothing is stopping someone from also picking up the books, annotating, and reading aloud themselves, or from dancing for that matter. I am making these tools that enable the study of art available, and it’s great if others find them useful as well.

People enter museums with very specific preconceptions of how to behave. Scriptorium questions this default, and audiences have to actively ask themselves what they are willing to do differently in light of what I am doing. Who says going to museums only means standing still in front of each artwork for a few moments? All I, my hosts, and audiences ever know ahead of time is when a performance is scheduled to begin and end. What happens in between depends on our collective decision-making in real time.

What projects do you have coming up in the new year?

Another project in Colorado Springs, happily for me. On March 6, an exhibition I curated opens there: “Where I Learned to Look: Art From the Yard.” This show was originally made at ICA Philadelphia, and I hadn’t planned for it to travel until the FAC asked. With the team there, we’ve organized some really special new additions that speak to the Southern Colorado context. I will also be a visiting artist at Missouri State University in March. There are a couple of other things in the works. I’m looking forward to 2026.

Hayley Richardson

Denver, Colorado

2025

Among the earliest monumental female nudes is Praxiteles’ “Aphrodite of Knidos,” a 4th-century BCE marble statue widely copied and reimagined throughout the ancient world. Ironically, the original was lost to history, surviving only as a ghost haunting countless echoes—from Botticelli’s “The Birth of Venus” to the legendary “Venus de Milo”—thus setting the Western canon for the female form with her sensual contrapposto and suggestive modesty.

Artist Patricia Cronin’s recent body of work joins this long lineage, paying homage to the Goddess of Love, Beauty, and Grace as a heroic figure in a world that rewards hatred, destruction, and indecency.

A striking series of monumental paintings and statuettes, “Army of Love” showed recently at Chart Gallery, a Tribeca space founded by Kasmin alum Clara Ha in 2019 with the curatorial vision of presenting art predominantly by women—notably Cronin’s first solo show in New York in almost a decade.

This isn’t easy or sentimental work—not for the world and not for Cronin. “What is so important to you that you are willing to lose for it? What are you willing to lose for?” she asked me recently as we discussed the crush of political losses sustained by women in the United States, echoing the broader global backlash to progress. This radical acceptance of loss—the willingness to fail, to lose—brings into stark perspective the real grit and determination that love requires. In “Army of Love,” Cronin offers art as a vessel for that determined kind of love: a compulsion as old as humanity itself.

Patricia Cronin as Interviewed by Rachel Dalamangas

Walk me through how the large works were made because as I understand, it was a multi-step process where the materials are impossible to tightly control, with much left to chance and experimental.

In “Army of Love” at Chart Gallery, the multi-layered assemblage paintings are entirely process-based and showcase three ways of paintings all in one. If there is a hierarchy of painting techniques, three are in these works, hand painted, mechanical reproduction, and ready-made objects.

After a research trip to Rome—location of the highest concentration of Aphrodite and Venus statues, many “copies” of the great 4th Century BCE attic sculptor Praxiteles’ “Aphrodite of Knidos” (350 BCE) renowned original onward—I was impatient to work large and dove right in.

Because Aphrodite is born of the sea, oil paint felt wrong. I turned to water-based paints, though I dislike acrylics and had never used them before. On raw, unprimed canvas spread across a plastic-covered table, I painted the negative space around the statues’ silhouettes. When I hung the canvas up to dry on the wall, I turned around and realized that aquamarine, cobalt, and turquoise paint had seeped through the canvas fibers, leaving abstract sea-foam apparitions I couldn’t anticipate or control. That unknowability of what I was making was exhilarating—a liberation that defied the old binaries of abstraction versus representation.

To preserve these ghostly abstractions, I photographed the residue on the plastic sheets and transferred them via dye sublimation onto sheer fabric. Hung on the wall over the painted canvas, the veils hover like apparitions of Aphrodite—always shifting, never fully seen. Behind them hangs a third layer: a ready-made polyethylene tarp, utilitarian and protective, echoing the ship’s sails from the ancient port cities where public and private temples to Aphrodite stood and supplicants prayed to her for safety.

Your work often begins with a kind of excavation of art history, sometimes resurrecting women artists cannibalized by the (heavily) male-dominated canon, and in “Army of Love” a kind of excavation of Praxiteles’ “Aphrodite of Knidos”—lost to history but felt in its influence on every depiction of the Goddess of Love to follow. How does history inspire and inform your work?

History is where I find the best ideas! Knowledge of the past sharpens my understanding of the present and arms me for the future. I always look for what I call “the magic three”: the right image or form, the right materials, to perfectly match the contemporary content burning in my mind for that moment in time.

After the 2016 election, with women being pushed out of public life and our democracy on the brink, the Tampa Museum of Art invited me to be the inaugural artist in their Conversations with the Collection series and respond to their Antiquities Collection. The first object I saw was a headless, limbless 1st-century CE torso of Aphrodite, one of the two most powerful female figures of the Ancient Mediterranean World, the birthplace of democracy. Fragmented by blunt force or centuries of neglect, yet enduring, she became the perfect focus for my imagination.

Praxiteles’ “Knidian Aphrodite,” the first monumental female nude in the western canon, once stood in the Temple to Aphrodite Euploia in Knidos, Turkey. Though the original is long lost, its fame lived on in Pliny’s writings and dozens of copies now housed in major museums around the world. On July 20, 1969—the day man planted a flag on the moon—archaeologist Iris Love, a groundbreaking lesbian, discovered that temple in Knidos. Cosmic conquest above, female divinity unearthed below.

At the same time, the Italian Arte Povera movement was at its height. Its artists embraced humble materials and methods, but most of the celebrated artists were all men. I wanted to shift the frame—introducing domestic materials historically coded as feminine: bleach, salt, tarps, contact paper. In “Army of Love”, classical ideals collide with those overlooked materials, reframing women’s labor and presence in art history.

You’ve referenced something you called the “economy of care.” What is the economy of care as it relates to this exhibit?

In the Ancient Mediterranean World, gods and goddesses held both civic and spiritual authority for their city-states. A powerful deity, Aphrodite was worshiped and beseeched for almost everything, marriages, business contracts, safe voyages, harvests, harmony in the community and the home. Unlike gods of war (although she helped with military victories also), her power was protection through love.

That is the lineage I claim. The tarps—today used to protect what we value when they shield homes after hurricanes—become metaphors for survival. Salt, bleach, and contact paper—tools of the domestic sphere for cooking, cleaning and decor—are monumentalized. In my hands, “army” no longer signals only conquest but an assembly for love, safety, and dignity. Compassion over conflict.

We’re living in a time where relations between men and women seem broken. Even in the political climate, in broad sweeping generalizations, it’s kind of strange to see the difference in how men are reacting and how women are. Sometimes it feels like we really are speaking a different language. How is “Army of Love” responding to the societal breakdown of decency, old against young, man against woman, one people against another, civilization, rationality and objectivity, and the rolling apocalypse that it feels like the world is becoming?

Critiquing misogyny and homophobia have always been at the core of my life’s work, and “Army of Love” continues that fight. As Jimmy Carter once said, “subjugating half your population is not only immoral, it is irrational.”

Today, hard won rights are being stripped away—from women, LGBTQ+ people, immigrants, and people of color. History tells us authoritarian regimes rely on scapegoats. On the first day, the Trump administration’s Executive Order “Defending Women From Gender Ideology Extremism And Restoring Biological Truth To The Federal Government” legally mandated only two genders, and their March 27, 2025 “Restoring Truth and Sanity to American History” Executive Oder targeted the Smithsonian Museums, deeming all art about feminist, LGBTQ+ and African-American history “Un-American Ideology” that “must be eliminated.” This is McCarthyism 2.0. This attack on gender and LGBTQ+ existence, was never just policy—it was ideology designed to erase histories and lives. “Army of Love” resists that erasure, insisting on visibility, protection, and dignity.

It also seems like art by women is increasingly referencing empathy and compassion. Some dismiss these as sentimental, but I think they take enormous discipline and depth. Do you have a definition of compassion or empathy that you were working from for this show?

I believe empathy is at the core of every great artwork. For “Army of Love”, I drew from British Classics Professor Mary Beard’s analysis of Sappho’s sole complete poem “Ode to Aphrodite.” Beard identified that Sappho was echoing Homer in book five of The Iliad, when Diamides prays to the goddess Athena I the midst of battle. By using the same content and stanza structure, Sappho subverts the entire male heroic order by changing men at war to women in love. Sappho might be the first appropriation artist!

That’s what I wanted: to redefine “army” not as a force of domination and destruction, but as a body in the service of protection, care, and compassion.

This is urgent. We live in a culture of government sanctioned cruelty—where the language of “lethality” replaces diplomacy, where white supremacist militias cosplay war on our streets. It is terrifying. And yet, in my studio, I am surrounded by towering female sentinels, and I feel safer. Only in safety can my imagination flourish.

By freeing these canvases from wooden stretchers, letting them flutter like sails, I gave form to liberation itself. Love, empathy, compassion—these are not weak. They are revolutionary. They are the only true antidote to cruelty.

At your studio, I loved seeing the test swatches of blue paint. What are you looking for when you experiment with color?

There are so many blues, and they are all so gorgeous. Aphrodite, being born of the Mediterranean Sea, I needed to do a deep dive into the array of hues. And then the spontaneity of the creative processes, especially with the watercolors made with sea salt, I needed a visual legend, so that while I’m in the middle of creating, I can SEE the color and act, rather than pause, pick up different tubes, and read the names of the blues and then choose.

When you work with watercolor, the pigment binds into the paper simultaneously while water evaporates away from the paper. I add more pigment, more water, and then I throw in Mediterranean sea salt which up ends the curing process. Time is of the essence, and one develops the necessary expert aesthetic calculations over decades of working. There are no short cuts.

I was also thinking about how art asks us to re-orient how we relate to others and ourselves, toward the experiences of someone or something else, familiar and unfamiliar, and by that virtue, the experience of having empathy itself expands our own scope of experience and capacity for perception. How do you hope viewers’ perceptions might expand through encountering your art?

Viewing art is a contemplative experience. And this “Army of Love” series is very open ended. I want people to walk in thinking they know everything they want to know about Aphrodite and encounter paintings that change that perception, slow them down, take them off autopilot, lower their blood pressure, and unplug for a little while. I’ve taken a well-known icon, Aphrodite, the Goddess of Love, Beauty and Sex and hopefully my conceptual choices and material experimentations has produced paintings and sculptures that reveal something they can experience anew and not just validate what they already know. That’s so boring!

The installation at Chart Gallery’s lower-level gallery creates an almost sacred space with a sense of mysticism. How intentional is this atmosphere? What role does the physical environment play in how you want people to experience the work?

Clara Ha, the owner of Chart Gallery, made the curatorial decision to keep all the monumental work upstairs and have all the intimate scaled works in the lower level. We call it the inner sanctum! After walking through the more public cult statue scaled works, viewers descend the stairs to the lower gallery, and you feel you are entering a sacred space. I’ve exhibited and collaborated with religious, secular, and industrial historic spaces, including a cemetery, a church, a villa, and a former powerplant. Creating contemporary art for historic architectural environments must be rigorously and sensitively done, out of respect for the historic space and the art. Anachronistic pairings are a favorite aesthetic strategy for me. These time traveling combinations expand both the original function of the venue and art. It connects us to a longer continuum of art, cultural practices, and humanity. I know we should be asking a lot more of art.

I noticed you used packing foam from a museum replica of Aphrodite to create two glass art works. How do you decide which found or utilitarian materials—like foam, canvas, and tarp—make it into the final work? What draws you to these everyday objects?

I like everyday objects for their transformative properties/potential. I animate them into a dual existence. And that expands their artistic and conceptual impact while also remaining true to their original purpose. My antennas are always on; I see the beauty and the potential in objects others don’t. The tarp is still a tarp, its function—to protect what we value remains the same, but I see its value and want to show others its inherent metaphorical properties. Elevating common domestic or utilitarian materials to the status of art history is a strong feminist statement.

What is the relevance of beauty in a world that is as you say is full of sanctioned cruelty?

Love and beauty are essential to combat and survive the rampant hatred and brutality. We are witnessing a race to the ethical bottom of who can be the most deceitful, the most bombastic, the greediest, the most selfish, the meanest, the most sadistic. The Ancient Greeks believed that beauty and goodness were connected, external physical beauty demonstrated internal moral virtue. While our 21st century selves might bristle at this concept, the beauty of the natural world is unanimously embraced as sites of solace and comfort after the daily barrage of chaos and cruelty. We must hold on to beauty in all its forms, especially now.

Rachel Dalamangas

New York, New York

2025

Image Credits:

KC Crow Maddux

Courtesy Patrica Cronin Studio LLC and CHART, New York

© Patricia Cronin

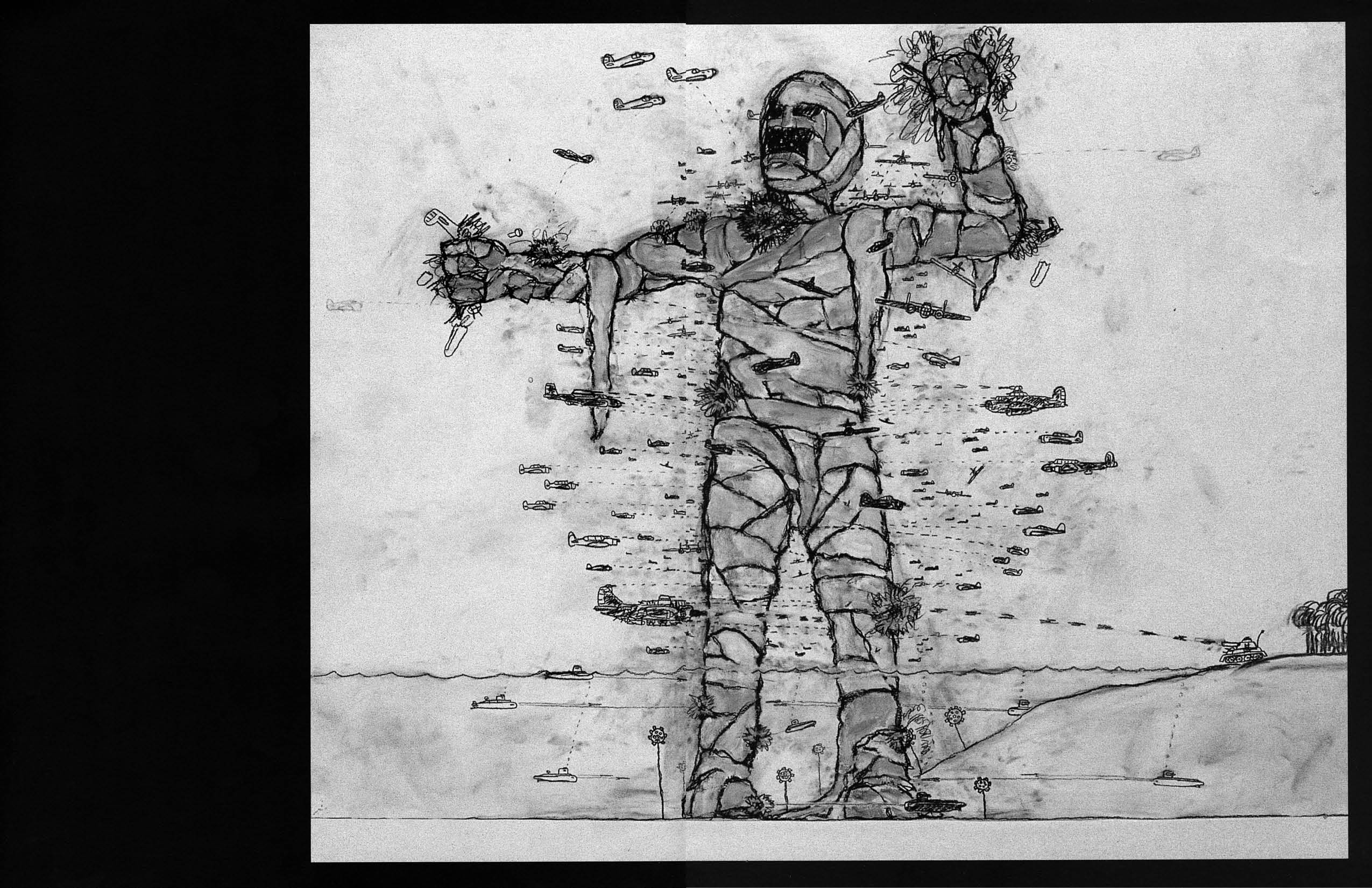

In dream dictionaries . . .

Airplanes represent:

Transcendence: Rising above limitation; perspective, elevation.

Aspiration / Ambition: Movement toward goals or ideals.

Transition: Departure, journey, or change of state.

Mummies represent:

Stasis: Something frozen in time; refusal or inability to let change occur

When mummies “come alive” in dreams, it can reflect the resurfacing of old material—memories, relationships, traumas—that were supposed to stay buried.

A mummy can symbolize the parts of the Self wrapped up—grief, anger, or desire that’s been bound and sealed rather than processed.

So if we are assuming “Airplanes & Mummies” operates the way a dream does, as a drama about the Self playing out on the stage of the unconscious, one interpretation is that the Shadow (Mummy) refuses to let go of past pain and allow itself to “die” so that the psyche can be reborn new. Airplanes represent Ego, which seeks to defeat the Shadow from limiting lofty ambitions and preventing change. This suggests that the Self is at war between the preserved past and the desire to move on. The artist has said in interviews that part of the work is of course the many interpretations that the audience projects onto it. But because what is depicted in the images is not actually random, because it is rising from somatic logic that the artist is tracking, it can make an intuitive kind of sense on sight that bears out conscious interpretation.

Annibale Carracci, Landscape with the Flight into Egypt, c. 1604, oil on canvas, 122 x 230 cm (Galleria Doria Pamphilj, Rome)

Annibale Carracci’s Landscape with the Flight into Egypt (c. 1604) is regarded as a breakthrough artwork in the genres of landscape and history painting. Carracci’s virtuosic attention to rolling greenery, atmospheric skies, shadowy thickets, majestic architecture, and shimmering water, populated with birds, camels, sheep, cattle and their caretakers envelopes the lunette canvas. The land is sublime and historic, more so than its biblical subject of the holy family. During her fellowship residency at the American Academy in Rome, Devon Dikeou, winner of the Jules Guérin Rome Prize, channeled Carracci’s emphasis on that which is often relegated as “background” or “in-between,” and titled this project “The Inconspicuouses.”

“The Inconspicuouses” is not a single physical artwork, but a conceptual framework for all the artwork she introduced at the Academy—whether it be Ongoing pieces with a 30-year history, collaborative projects, new creations, or ephemeral moments that continue to resonate with time.

Devon Dikeou as Interviewed by Hayley Richardson

The American Academy in Rome, McKim, Mead and White Building, Photo by altrospazio

As the recipient of the Jules Guérin Rome Prize, you arrived at the American Academy in Rome (AAR) for a 10-month residency in September 2024. What were your initial impressions upon arrival?

Flabbergasted frankly. The history, and the physical presence of the McKim, Mead and White Building changes you. The relevance . . . You feel it even before entering under the watchful eyes of Janus, god of the transitions, endings and beginnings . . . Janus is a symbol of the Academy, proudly yet discreetly displayed above the front entrance. Back to relevance . . . So, the next word that comes to mind is adjustment. Adjusting to the building, the people, and of course Rome.

Your Ongoing artworks, like Suck, continued to expand at AAR while you simultaneously conceptualized and executed brand new work. I am curious about the most recent developments in your studio . . . what can you share?

The moment you arrive and get the keys, they (the studios), are overpowering just on scale alone. My studio, 263, the Mr. and Mrs. David Rockefeller studio, has a window that is superbly set in another era, another time—that of McKim, Mead and White and all their glory. The window is a single window made of 12 large panes of glass and stretches vertically, practically to Mount Everest. Through the window the immediate surroundings offer a landscape that includes giant umbrella pines, regal conifers—reaching like fireworks to the sky . . . And what are windows but canvases, and mine is “a readymade” given by McKim, Mead and White, and this formed the genesis of the “The Inconspicuouses,” the title of my Rome Prize project. “The Inconspicuouses” explores the emergence and nature of landscape as a primary subject matter through the lens of Annibale Carracci . . . And this window, with the landscape spilling in, became my canvas into those Carracci gestures and nuances.

Devon Dikeou, Annibale / Suck, 2024/25 Ongoing / 1991 Ongoing, Live Performance as the Wind Creates Movement with the Umbrella Pine Outside the Window at the American Academy of Rome, Mr and Mrs David Rockefeller Studios, 263 / Live Performance as the Fan Creates Movement with the Straws Made for the Rome Prize

To counter this gigantic window, real and literal, and magically surreal, I eventually came to Stevie and “Landslide.” Supposedly written from a window in Aspen, where Stevie Nicks worked as a domestic, my impulse was to photograph the landscape from the same window that inspired that “landmark” song. But its location is a coveted secret, and unknown, except to Stevie, so I decided to commission Ana, an Aspen domestic, to photograph her idea of a landslide from a window from our home in Aspen . . . Ana’s image, with all its “Star Trek” reflection, was enlarged and printed from the printouts of my AAR “vision board.” It is yet another study in landscape using collage, trompe-l’oeil, and, with a wink to Annibale, to that newly discovered middle ground and landscape as a primary subject matter. And what is landscape as a primary subject matter? Well, my answer became two windows facing off . . . And middle ground, that lovely in-between . . .

Devon Dikeou, Aspen Snow (Rome Prize), 2024/25 Ongoing, Various Blends of Salt Spread over McKim, Mead White Building Floor at The American Academy in Rome and the Tracks of Viewers

I affirm, and continue to argue, landscape can be anything . . . And I tried to make anything . . . Anything that could bridge these two canvases, two windows, two views, including a bunch of straws (Suck), an Ongoing piece of mine since 1991, that exists as a series of straw bouquets, usually used, but not in this edition . . . Straws can desolate our landscapes/oceans/planet, but here they just shimmer and shake against the mighty pine fluttering its way to majesty in the temporal wind. Look the other way towards the Aspen window for a landscape of another kind . . . No pleached elegance, but a futon covered in airplane blankets snagged by AAR Fellows and their Fellow Travelers, and visiting friends . . . It’s called Red Eye and rests underneath the Aspen window. And then there is the salt . . . decidedly spread all over the studio floor in mounds, in spatters, in the way perhaps snow looks and sometimes feels, and contrasts with the red terracotta floor, while the white artificial weather is a stand-in for Aspen snow . . . Funny, you put salt down to melt snow . . . It does look like a first snow on Main St or simultaneously the remaining days of Carthage . . .

Devon Dikeou, Red Eye (Rome Prize), 2024/2025 Ongoing, Airplane Blankets from Lufsthansa, United, American, Delta, Air Canada, and Latam, Collected by Fellows and Fellow Travelers on Transatlantic Flights

A reoccurring element of your practice is allowing your work to permeate beyond a prescribed exhibition space, like placing installations outside the booth at an art fair or utilizing unconventional settings like offices, parking lots, or retail spaces. What kind of activations occurred outside of your studio during your residency?

Devon Dikeou, “Out, out damn spot” – Macbeth, Shakespeare (Rome Prize), 1992 Ongoing, Happening: 300 Warm Towels Served to Viewers, Who Enjoyed, Used, and Discarded Towels, Relic of Happening, Variable Dimensions

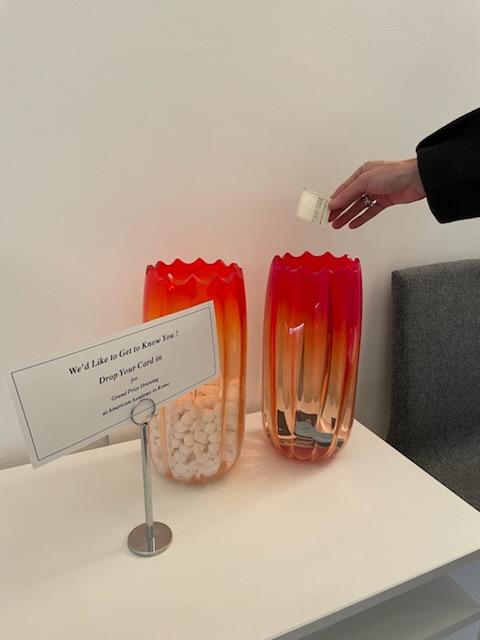

Well, I’m not a typical studio artist. It took a while to get used to my new surroundings, but a typical studio visit with me explores my surroundings, most likely my home, and the Academy was my surroundings/home. Soooooo the vehicle for that was the McKim, Mead and White Building, often through interventions, like Out, Out, Damn Spot in the laundry room, Hot, Shake and One Little Piggy in the communal kitchen, Suggestion Cards with a prompt to drop the card in the Suggestion Box, (which is right next to the mail boxes), to Pay What You Wish but You Must Pay Something, the donation box series originally exhibited at NADA Miami in 2014/currently on view at the Dikeou Collection in which 20 American museum institutions (so far) have participated. Each museum provided schematic plans of their donation box for replication and visitors make voluntary cash donations. The money is documented and forwarded to the institutions. The donation box was not realized at AAR.

Devon Dikeou, We’d Like to Get to Know You (Rome Prize), 1991 Ongoing, Salviatti Vases, Placard Querying Viewer’s for Business Cards with the Potential to Win Prize, After Dinner Mints, Viewer’s Business Cards

Plus, We’d Like to Get to Know You, placed in the Residential Life Office. Eventually, the lovely Titziana, one of a few who kept us caffeinated and more, picked the Grand Prize Winner out of all the business cards deposited into the American roadside tradition that was gussied up AAR style. The business card picked by Titziana from the Salviati vases belonged to AAR’s Arts Director, Ilaria Puri Purini’s, daughter. Is the fix in . . .

Devon Dikeou, Contrivance: Rome Prize, 2017 Ongoing, Oil Painting on Canvas of Tool Room in David Rockefeller Studio, 263, Rome, Dimensions Variable

Of course, the newest additions of The Niney Timeline, which chronicles the life and times of my security blanket, Niney, as she traverses the art world, including the McKim, Mead and White Building, while resting comfortably in her bedroom/our residence. A toilet paper piece, Entertaining is Fun, installed on the wall with toilet plungers in the WC. There’s Contrivance, a series of photo-realistic paintings of the tool rooms of the various non-studios I’ve had, including at other art residencies. It is a nod to the studio—an intervention that adds to the cycle. My AAR tool room was in the closet of my McKim, Mead and White Building studio. I displayed the photo-realist painting opposite the actual tool room in the nave of the entry, peeking out into the world of in-between windows and lands . . .

Devon Dikeou, Velvet rope (Rome Prize), 2024/25 Ongoing, Dimensions Variable

And lastly, Velvet Rope, in which I used the AAR rope stanchion placed at the foot of the staircase—meant to keep those deemed “not worthy” away from private areas of the Academy. I acted as bouncer . . . And I let everyone in, one by one, marking them with a Sharpie, just like they were getting into Studio 54, Palladium, the World, Area, or even the Academy. It’s a very exclusive club . . .

One of the most enriching aspects of residencies is the opportunity to collaborate with fellow residents, as well as with locals in the community. What kinds of collaborations were you able to partake in at AAR?

Julia Rose Katz, awarded the Anthony M. Clark Rome Prize, (Circe’s Wand: Reimagining Antiquities in Early Modern Europe) and I were paired for ShopTalks—an AAR program which typically pairs a visual artist with a scholar to make a joint presentation based on their projects/practices and talk about the cross-pollinating that might happen . . . (This program is not open to the public). We decided to not only make a presentation of both our practices, but also, in a unique manner, to make/do something that eventually could be shared with the public, challenging the traditional lecture model. I presented in the form of a studio visit that encompassed the McKim, Mead and White Building. Julia explored her study of how early Modern artists and restorers creatively reimagined damaged ancient sculptures, and how her personal affliction on her leg has influenced her vision towards study and life with regards to film, classical sculpture, modern presentations of sculpture, installations, fashion, semiotics, bricolage etc. The platform of our collaboration is a book . . . We combined our shared interests, and each chose approximately half the images and published a limited-edition run under zingmagazine books. Permanent Accident was the result.

Lizzi Bougatsos, Self-Portrait, 2012, Ice, Artwork curation by Devon Dikeou and Julia Rose Katz at American Academy in Rome, March 2025

Further, drawing from our unique position as curators, Julia and I decided to raid Dikeou Collection and recreate a wonderful installation in the foyer of the Academy where much of the Archeological work was happening—with all the fragments and fountains and study tools . . . There, a leg in the form of an ice sculpture by Lizzi Bougatsos entitled Self-Portrait stood tall and wildly clear in its medium. An inherent vice by nature, the ice glowed among treasures from the ancient world, still giving and sharing their secrets. Self-Portrait is both a sculpture and a performance, which lasts about fours hours as the ice melts and eventually collapses on itself, culminating with the destruction of the leg, because that inherent vice would be painfully bad for the immediate surroundings. Julia did the honors.

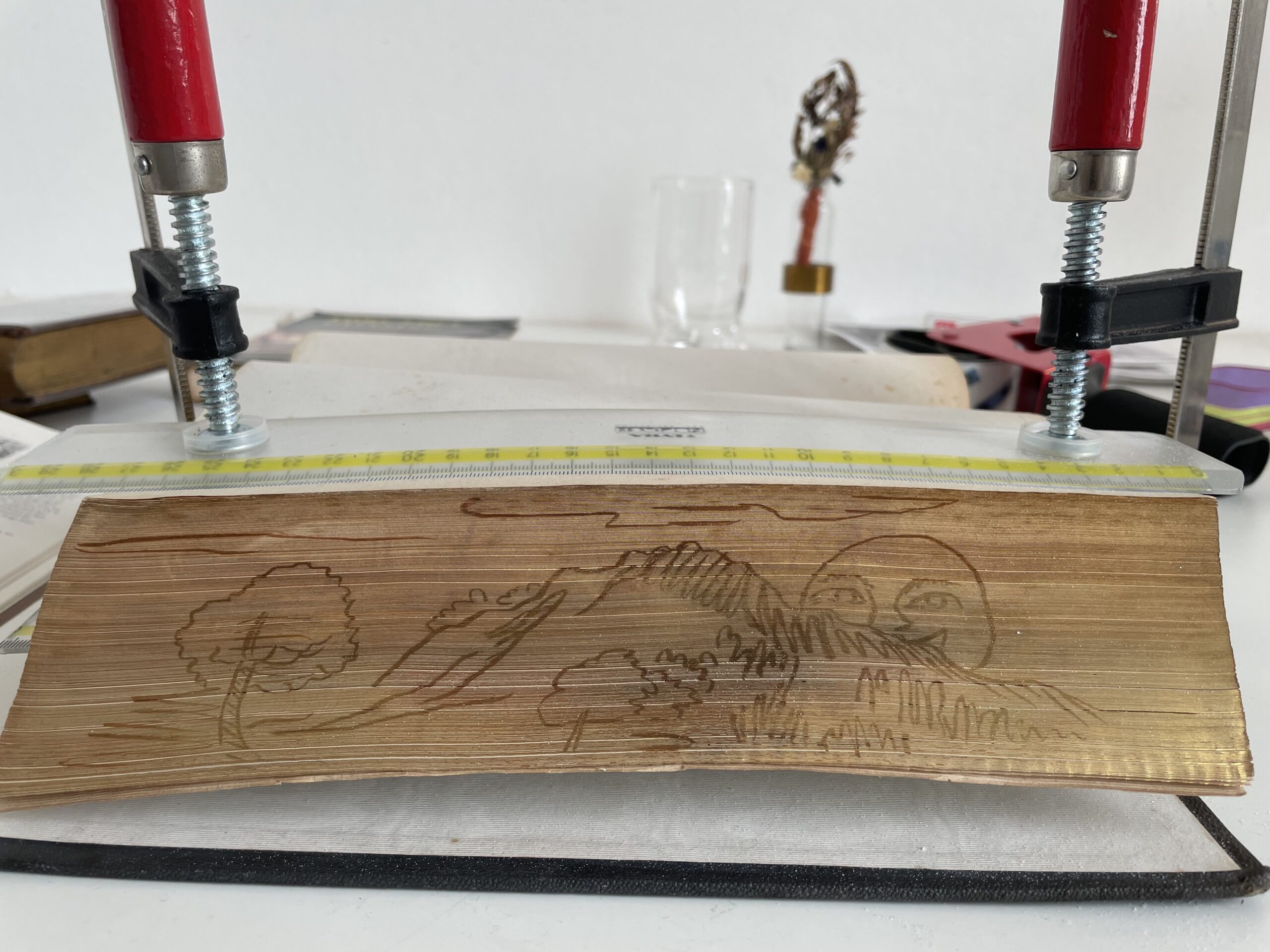

Katherine Beaty and Devon Dikeou, Fore-edged book, after Annibale Carracci, 2024/25

I also collaborated with Katherine Beaty, winner of the Suzanne Deal Booth Rome Prize (A Technical Study of Italian Archival Bookbindings). Together we created a fore-edge book, which are usually insignificant titles but with a gold edge on the paper . . . Bend and twist the paper of the book and it reveals a genuine treasure, a painting of some sort . . . I happen to have a collection of fore-edge books given to me by my father . . . And thinking about Carracci, I was inspired to paint a sketch of his on the side. Strangely enough, Katherine and I met just before the award announcement ceremony at Carnegie Hall and we spoke about fore-edge books and naturally what our projects might entail . . . I’m not that talented of an artist, but she kept encouraging me . . . I’m a little “grey cell Poirot” type-artist. But eventually, we decided to create a fore-edge book together, with the image by Annibale that I selected and her expertise in all things books, including painting on them. It’s now the very first fore-edge book at the Academy’s library.

Prima (Rome Prize), 2024/25, Collaboration and Ballet Performance by Prima Ballerina, Holly Dorger, of the Royal Danish Ballet at the American Academy in Rome

Another collaboration was with the prima ballerina, Holly Dorger, of the Royal Danish Ballet. When she visited the Academy, I invited her to do a pirouette and a leap. What she did was a wonderful improvisational performance that ended with me asking for just a bit more, that fantastic leap, all the while Bea, an intern at the Rome Sustainable Food Project, sliced 100 pounds of roast beef on a professional meat slicer, and I made sandwiches for my performance piece, One Little Piggy Ate Roast Beef. I loved sharing dance and food with two other amazing types of creatives . . . It was a great three-way . . . One with someone I just met (Bea) and the other my cousin (Holly), who I know in a forever way.

Shake . . . Ongoing since 1991, the piece is almost improvisational. Moving to NYC, I immediately bought a set of Po-Mo salt & pepper shakers at MoMA . . . They looked good, but they didn’t function. This was followed by another purchase on Bowery—Wayne Thiebaud diner style shakers. Suddenly, I had a collection. Much later the real collection emerged . . . And much, much later for a group exhibition at PS 122–where each artist was given a snow globe as an artistic prompt. My snow globes were recreated into S&P shakers with the actual shakers submerged in the salt and pepper within the snow globe. It is a portrait of friends and travelers over time . . . From the 90s to now . . .

Devon Dikeou, Shake (Rome Prize), 1991 Ongoing, Installation View of Snow Globes Altered to Become Functioning Salt and Pepper Shakers, Each Filled with Salt and Pepper, and when Used, the Diminishing Salt and Pepper Reveals the Actual Accumulated Gift Collection of Shakers, 3 1/2”H x 2 1/2” in Diameter

That gesture was something I felt immediately applicable to the environment at AAR, all the different passions and personalities . . . I realized and felt a group portrait would rock, so I engaged all fellow Scholars and Prize Winners to collaborate in a salt and pepper project. I gave a small stipend to purchase two sets of S&P shakers, and I would create two sets of my ongoing Shake project, one for them as a self-portrait of their time at AAR, and the other which would function as a group portrait of our time at AAR together. Almost everyone participated, but sometimes I found ways for those tardy to the party to represent.

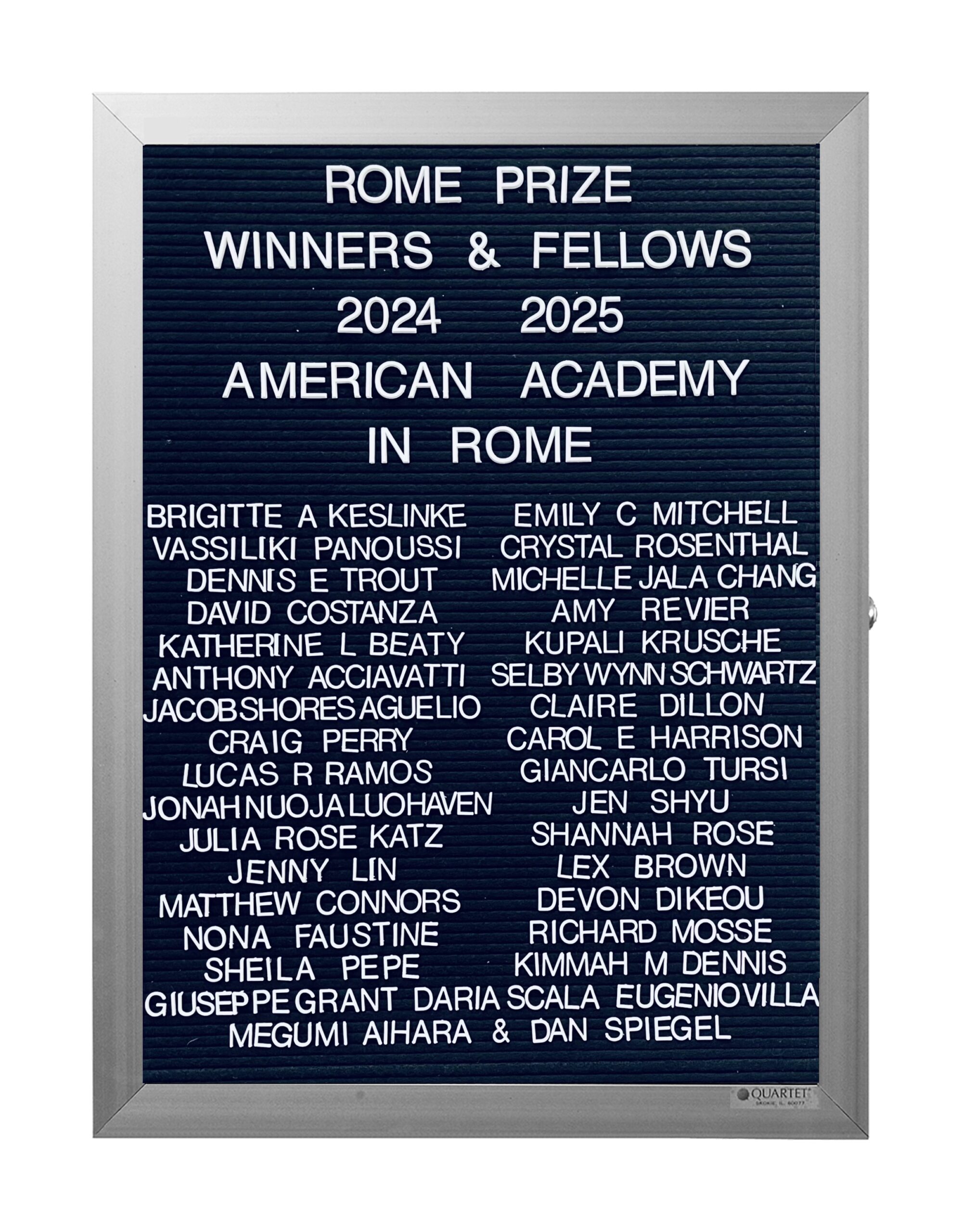

Devon Dikeou, What’s Love Got To Do With It? (Rome Prize), 1991 Ongoing, Rome Prize Winners & Fellows, Lobby Directory Board Listing Artists, Gallery, Curators, Exhibition Titles, Dates Replicating the Lobby Directory Board at 420 West Broadway (Series Initialized for the 1st Group Show in which the Artist Exhibited, and Made for Every Group Show Thereafter), 18” x 24”

Perhaps the longest and most important collaboration, however, began in 1991 with my Ongoing series “What’s Love Got to Do With It?” Inspired both by the Pictures Generation and their use of appropriation and by my aspiration to exhibit in the storied Leo Castelli Gallery, I replicated that equally storied lobby directory board. The one I created sported the names, curators and dates of one of the first group shows in which I participated . . . I realized this board could not be the only one, so I created one for every group show since (about 160 now) plus the table of contents for each issue of zingmagazine, and Dikeou Collection acquisitions. My first proposal as Rome Prize applicant some 15 years ago was to recreate this series for all Rome Prize Winners . . . The first I made was for class of 2024/25. Ongoing . . .

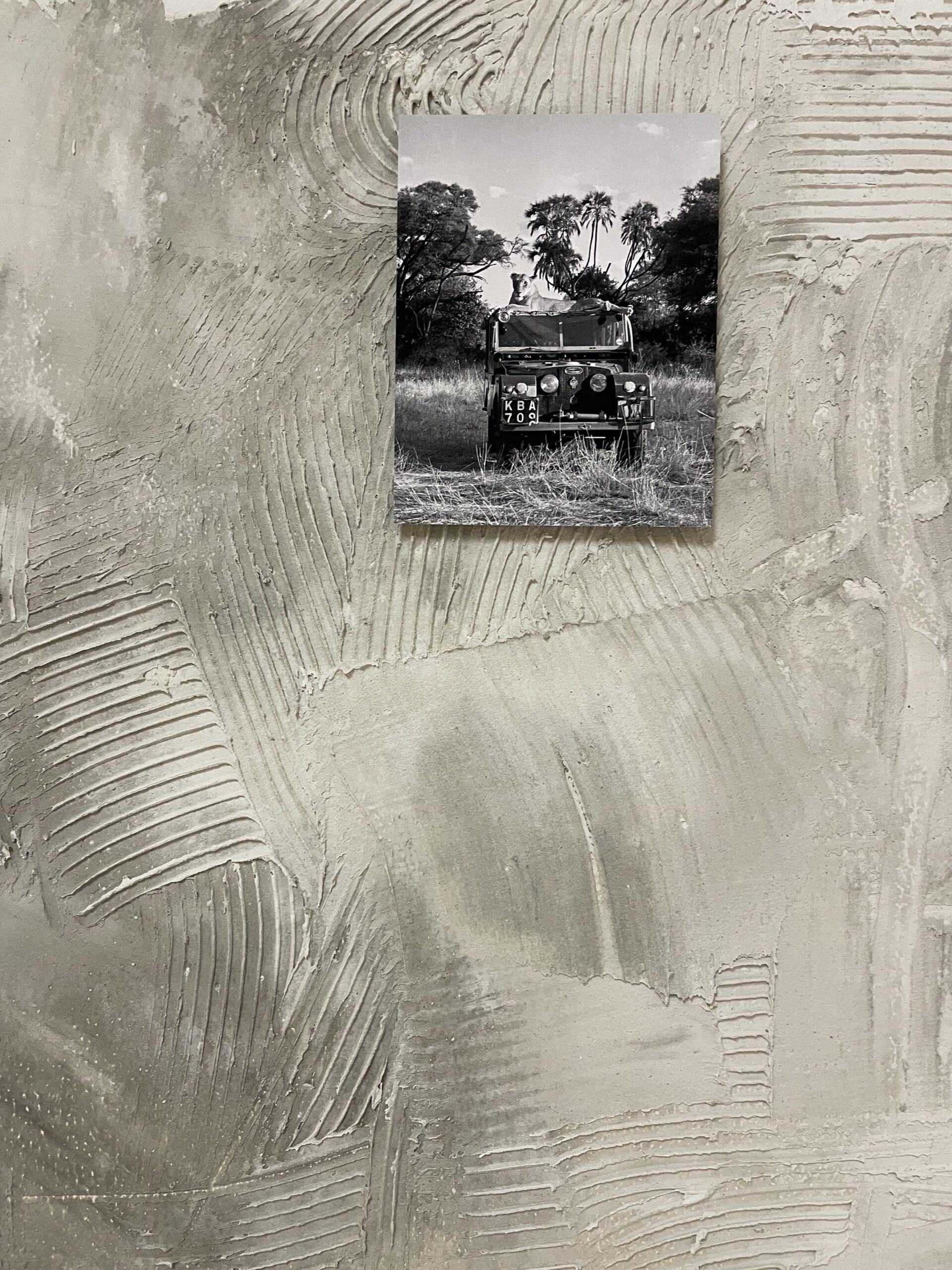

Another new work you realized during your residency blends the myth of Hercules with that of Elsa the lioness from Born Free, creating a completely new narrative about labor, care, conquest, and sacrificial love. Additionally, the presentation of this work at Seconde Vue, a location outside of the Academy, extends our conversation about collaboration and exhibiting art in non-traditional spaces. Who were your collaborators for this new work, both in myth and reality?

One of the goals of the Rome Prize is to embrace an aspect of Rome that will enhance your project. So in my case, “The Inconspicuouses,” it was only natural that I visit the Carracci masterpiece in Palazzo Farnese, aka the French Embassy . . . Naturally, it’s quite an ordeal as it IS a governmental building. But I did manage to visit five times. And the thing about Rome is, it’s full of is all these fabled miscreants and heroes portrayed in statues, frescoes and a plethora of other mediums depicting myths, history, who’s who and more . . . And Farnese adopts both Hercules and Carracci . . . Hercules as a mascot and perhaps Carracci as well. (Notoriously, Carracci is paid a pittance for his exquisite cycle, “The Loves of the Gods,” which includes Hercules). As the myth of Hercules goes, he must complete 12 labors as penance for bad behavior. The first of which is to kill a lioness, which he does with a club. He sports the skin like a Michael Jordan jersey in game two until victory in seven. At the Palazzo there’s a magnificent replica (original in Napoli) of Hercules leaning on his club, skin draped over his shoulder. It’s a great preamble for what’s to come as you tour the Embassy . . . The Carracci cycle—a cycle based on mythological subjects, including Hercules.

But back to the show at Seconde Vue. “The Inconspicuouses” is most decidedly about something Carracci explored outside his work at Farnese, and yet he snuck something in . . . Beautiful snippets of landscape teasing characters in the cycles and the architecture as well. And I very much felt that I’d like to sneak something out of the Academy. And that was an off-site exhibition . . . addressing other aspects of Carracci’s practice and that of my own.

Devon Dikeou, Club, 2025 Ongoing, Found Object from the American Academy in Rome Garden;

Devon Dikeou, Hercules, 2025 Ongoing, C-Print of a Found Object from the American Academy in Rome Garden Positioned to Replicate Ercole Farnese, Farnese Hercules, 3rd Century AD, Club as Leaned on by Hercules Statue Signed by Glykon

The result: “From Fulfillment to Adaptation.” Shown at a Seconde Vue, a concept space by Federica Dollfus Di Volkersberg and curated by Guglielmo Corbo who was introduced to me by a French curator Gèraldine Postel. The exhibition entailed two pieces. A club found by Andrea and Fernando on the Academy campus—ostensibly to fix a sagging clothes rack—but turned out too short for the task. I couldn’t not see it as Hercules’s club, forlorn in the corner, without function. So I adopted it, as I often do, and photographed it—letting the object make the piece, both suture and photograph.

Elsa the lioness of Born Free fame laying on the roof of the Adamson’s Series 1 LandRover, Kenya, 1960, 26.4 x 34.5 cm, © Joy Adamson

But what’s the club without the lioness, and Elsa from Born Free is that, a modern day myth . . . It was a nice contrast to what I was showing at the Academy. Hercules has 12 labors, Elsa one. I love them both for their humility . . . And their spirit. One is born free; one fights to gain that . . . spirit/freedom . . . Or is it the other way around?

Your work as an artist, collector, curator, and publisher/editor is deeply informed by the different platforms in which art is experienced and exchanged, be that between people and/or spaces depending on their respective roles and contexts. Considering the vast size, history, and diversity of Rome and the generous amount of time spent there, did the city itself spark new insight or perspective within this guiding modality of your practice?

Janus. The god of the in-between. Looking both ways, Janus is two faced, not in a catty way, just recognizing the give and take in life and most certainly the creative process. I don’t go to the studio every day . . . And my “practice” traverses lots of different arenas as you mention. Editing/publishing a magazine (which is hosting this very interview), and a collection of contemporary art exhibited in five locations in Downtown Denver, including hosting studio space for the Clyfford Still Museum’s Institute Residential Fellowship Program, as well as my own personal practice. So, I have a lot of chips on the table . . . Hedging this way or that . . . And Rome is a little like that. It’s slow in a way that ancient places are. It gives you insights and glory, little by little. Even when they are the big things . . . Like the Sistine Chapel or the Coliseum, you crawl along and are no different than the pilgrims, tourists, and those just drawn to history and beauty over the years or the locales visited. Which is why the 10-month duration of the residency is essential somehow . . . It used to be longer . . . I wish in a way it was.

Janus above the front door of the American Academy in Rome’s Mckim Mead & White Building (photograph by altrospazio)

But AAR changed me . . . As one creates, it seems the process is intuitive among visual arts, but for my practice, intuition is not consciously there, and that means adjustment . . . My practice uses planning and time realization, it is very much edited long before it is executed, and that’s not the case from my experience of what to produce during a residency at AAR . . . Suddenly, time and Rome changed and sped up, pushing, coaxing new things out of me that I’m still feeling . . . New ways of working, even making work at the last minute, moments before the Uber ride to the airport, and even now at an elevation of 5280 in Colorado I’m still thinking about those 1200 hundred meters in Rome. These moments and works in-between fast and slow, and adjustments made me a better artist. I hope what I imparted at AAR was resonant, in slowness through adjustment in speed.

Doria Pamphilj Gallery

Share. Which is always been my inclination. But share in the most personal way . . . somehow in the end that’s the most meaningful. Doria Pamphilj Gallery . . . it’s where the Carracci masterpiece Flight into Egypt is housed, and that is my supposed inspiration . . . But on that foggy day, when I visit that old friend, in the grey loneliness of a treasure of a museum, or conversely in the blazing heat while the slow dark treasure seeps out . . . Either way it’s good to recognize those treasures within treasures . . . And that’s what the Academy epitomizes at its best. Look left and right . . . Sinistra . . . Destra . . . Janus.

Hayley Richardson

Denver, Colorado

2025

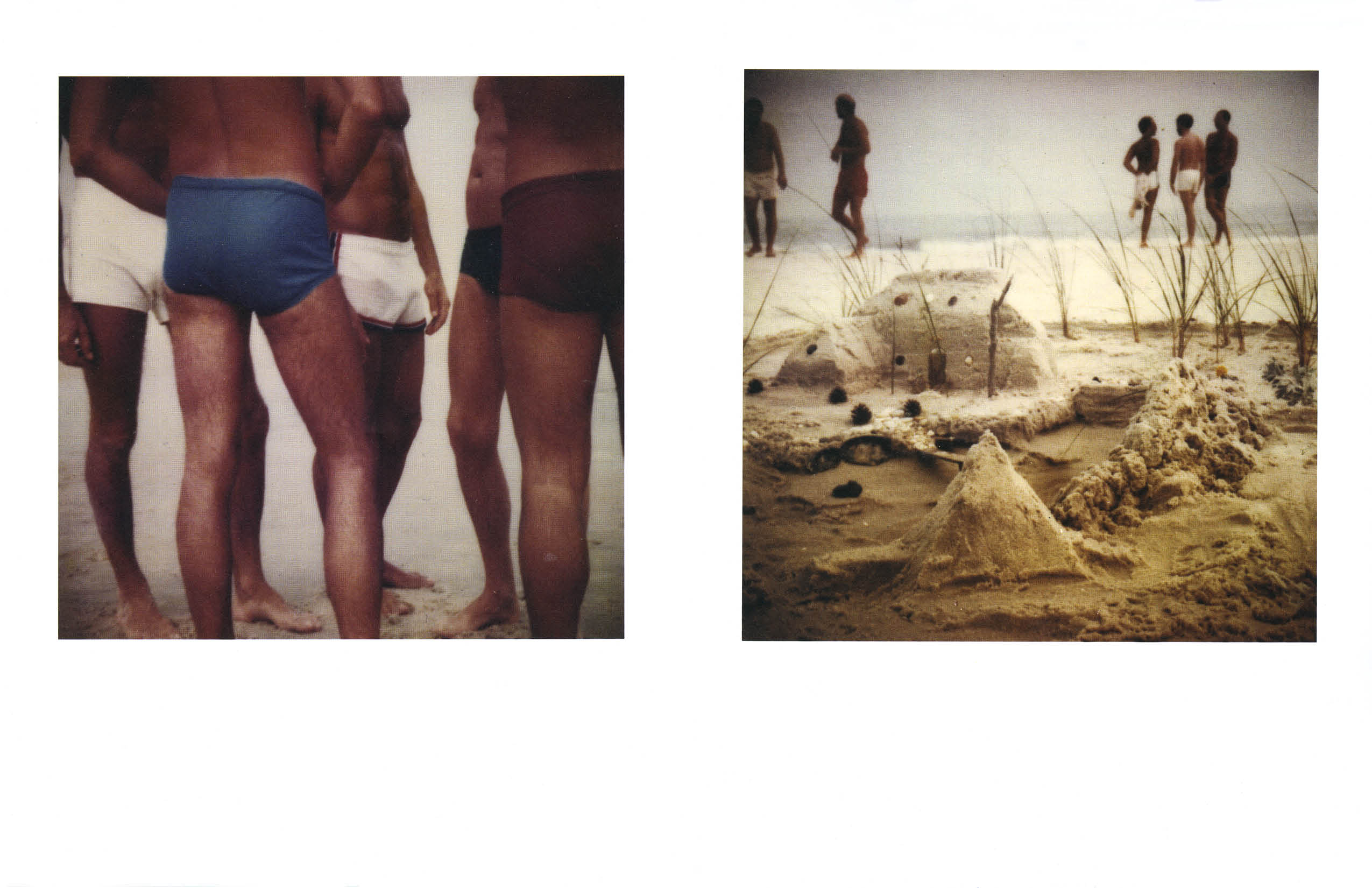

Joseph F Lovett’s passing this summer marks the loss of a pioneering voice in documentary filmmaking and LGBTQ+ cultural memory. To issue 21 of zingmagazine, Joseph joined Mary Barone in curating a selection of Tom Bianchi’s Polaroids from the 1970s, which were incorporated into his 2005 film GAY Sex in the 70s.

In his curatorial note, Joseph recalled watching Bianchi take these same Polaroids decades earlier and being struck by the sensuality they captured. “I was so happy to be able to use them in the film,” he wrote, “and to show a selection of them in zing.”

Rachel Dalamangas

New York, NY

September 2025