Yolanda Fauvet, exhibition curator

What am I? ¿Qué soy? at Museo de las Americas showcases Anthony Quinn’s rich and varied artwork, highlighting his lesser-known talent as a visual artist alongside his renowned acting career. Through self-portraits, sculptures, and prints, Quinn explores themes of identity, heritage, and self-discovery. His work reflects his Mexican-American background and the duality of his public and private selves. The exhibition emphasizes Quinn’s lifelong journey of examining his origins and the roles he played both on and off screen. I chatted with exhibition curator Yolanda Fauvet about how his art invites viewers to engage with their own identities, encouraging reflection on how personal and cultural histories shape who we are.

Interview by Hayley Richardson

How did you first become acquainted with Anthony Quinn’s artwork? What is the backstory of how this exhibition came to fruition?

I didn’t know much about Anthony Quinn when I was invited to submit a curatorial proposal about his artwork last October. I hadn’t seen any of his movies that I could recall, so most of what I learned about him I had read online. And I have to admit, it took me some time to warm up to him and decide to submit a proposal. Not everything that comes up on the search engine is exactly favorable and, as I went down the rabbit hole of movie trailers on youtube, I felt sensitive to the disrespectful ways many of the female characters where treated or portrayed. To that point in particular, I had to remember that many of these films date to another time and reflect the social norms of my grandparents and not our own (and heck, I even have trouble watching movies and shows I grew up with now). But in a time when we are now pushing to make room for more non-hetero male perspectives, I felt I needed to find something personally meaningful to connect to before being able to stand behind this project.

And then I came across a 1994 tv interview conducted in Spanish alongside Mexican actor Ricardo Montalbán (you may know him from Fantasy Island or Planet of the Apes). Both actors were being commemorated for their contributions to enriching Mexican cultural pride abroad. As I watched, it caught my attention the ways in which Anthony Quinn’s Spanish was subtly and not so subtly corrected, an experience that hit very close to home and has often left me feeling vulnerable. It was in this shared vulnerability that I was able to connect to the human experience of growing up as a Mexican-American in the United States. Albeit in different eras (Quinn was born in 1915 and I in the ’80s), it was inspiring to see how he was able to shrug off with a smile and joke something that, when done by certain people and in a certain tone, has hit like a dagger and made me feel like I didn’t belong in a country that I’ve longed all my life to be a part of. So all of a sudden, deep in the pangs of my always longing heart, my quest to explore different aspects of Quinn’s bicultural identity alongside his artwork became apparent. I don’t think it couldn’t have fit a better audience in Denver than that of Museo de las Américas, a museum dedicated to exploring and celebrating Latin American culture through art.

Once my proposal had been chosen, the next major challenge was narrowing down the selection of work. Museo is not exactly a small space, but Quinn was very prolific, and it took me three site visits to the Anthony Quinn Estate to make my final selection. Several works on paper, sculptures and paintings of all scales, and a vast personal library fill the equivalent of three barns, not to mention the pieces displayed throughout the Quinn family home! Fortunately, his wife Katherine has done a wonderful job of preserving and cataloging his work, and it was such a pleasure getting to know her and her own story over this past year. It was in conversations with Kathy during my visits to their beautiful Rhode Island home where I began to get to know the “Tony” she knew, the “Tony” that loved his family and was a fierce creative being, not just a juicy subject for the tabloids. In these conversations, I also learned of the many youths that the Quinn family has inspired and supported since his passing through the art scholarships given by the Anthony Quinn Foundation. And just as Kathy’s face would light up when speaking of her husband, I began to notice a similar effect on other people I spoke to who knew of him through his films.

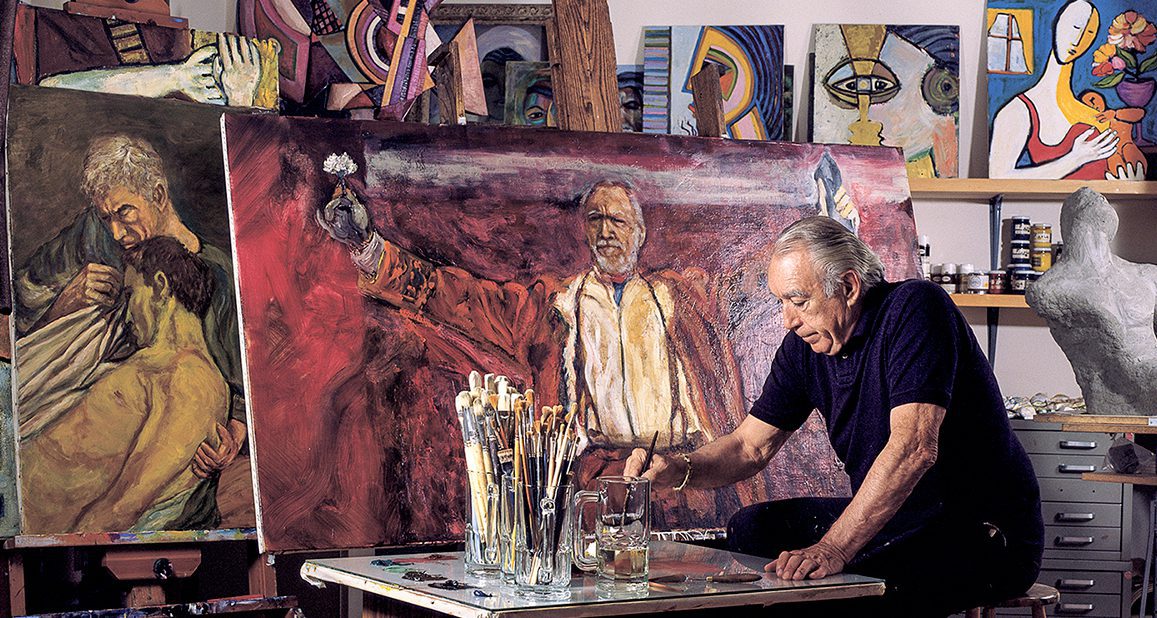

Anthony Quinn in his studio, image courtesy of National Hellenic Museum

So through my conversations with Kathy and with close friends who are bicultural artists working today (Adán de la Garza, Ethan Bradford Barrett Villarreal, Viera Khovláguina, and Amanda Beard Garcia), I began to identify a progression of self-portraiture in Anthony Quinn’s work that would allow me to talk about identity, centering on the question of What am I? Which is something we’ve all asked ourselves in one way or another but can be particularly poignant for someone who was born in Chihuahua during the Mexican Revolution to an indigenous Mexican mother and first-generation Irish-Mexican father and grew up in LA after living in Texas along the US-Mexican border for the first five years of his life. We can only imagine the different waves of stereotypes Quinn was confronted with while working during the Golden Age of Hollywood up until his last movie filmed in 2001. Even though much of his artwork doesn’t overtly address topics we’d expect to see in Chicano or Latinx art today, his body of work gives us the example of someone who dared to ask life’s difficult questions, and we can find a camaraderie in the inner searching he portrays.

Listed throughout the wall plaques of the exhibit, I take the viewers through reflections that expand on the question of What am I?, like, for example, What could have been? This is posed next to an excerpt of Quinn’s writing displayed in golden text in which he himself asks if the Spirits were mad that he had left Chihuahua. Even though he and his mother left out of necessity, there is still a wonder deep within him of what would have happened if he hadn’t of left the place he was born, which I speculate is also something many people living in Colorado can relate to. How many of us are living in homes where we or our parents come from another culture or country?

The title of the exhibition, What am I? ¿Qué soy?, intrigued me because I have often wondered what actors do to psychologically maintain a sense of self when they work so intensely to transform into roles that are constantly shifting. But even prior to becoming an actor, Quinn felt a deep desire to know and understand himself culturally, spiritually, professionally, socially, and creatively; a quest that spanned his entire life and manifests in his artistic legacy. While curating this exhibit and learning about his life, do you feel there are any artworks (or eras) that most potently capture his essence, his sense of self? Perhaps this question has no definitive answer, but I’d love to hear your thoughts.

To your reflection of how an actor would maintain a sense of self when giving themselves fully to their roles and fictional storylines, Anthony Quinn blurs those lines in works where he has depicted himself as characters he portrayed, such as the bronze cast of him as Zorba the Greek (1964) or the painting where he appears as Ukrainian Archbishop Kiril Lakota in the Shoes of the Fisherman (1968). Because he did this for only select films, we have to ask what was it about those roles that compelled him to create these artistic portraits?

We could speculate they helped him understand his characters more deeply, but I’d also like to posit that he found an affinity somehow to what those characters went through. I’m thinking specifically of the painting where he depicts himself as the biblical Barabbas in a barren desert who at the end of the film is crucified and we as viewers are left to decide whether he died believing in God or not. This theme calls to mind another painting in the exhibit titled Promises-Religion that is part of Quinn’s Unfulfilled Promises triptych (1975-2000). This large-scale painting depicts a preacher that is standing next to a crucifix and emphatically addresses a large crowd. While we don’t know the nature of the broken promise in this case, this scene may be a reference to a short time when Quinn was a preacher himself before he began acting.

Anthony Quinn: What am I? ¿Qué soy?, installation view, Unfulfilled Promises triptych, image courtesy of Museo de las Americas

We also know he used to make art on set as a way to help him stay focused in his characters, and perhaps it was a way to ground himself as well. When visiting his barn studio, Katherine showed us the portable box full of the wood carving tools he’d take with him wherever he travelled. In a floating vitrine near his movie portraits that displays four small-scale mounted maquettes, we also have a small wooden carving possibly titled for another film he starred in, Bedouin. Looking at these intimately carved miniature sculptures, I imagine him collecting wood from the different regions he visited while filming or working from a found piece of driftwood from his walks along the shore.

The title of the exhibit comes from the same interview I previously mentioned where Quinn tells an anecdote about when he was a young boy. Given the task of filling out his nationality on a form for school, he asks his father ¿Qué soy, papá? What am I? Which, if we recall his multicultural background, it was not an easy question to answer, and probably less so in the 1920s in the United States. So his father, perhaps in rebellion against this form of categorization, wrote every nationality that he could think of on that card. Quinn tells this story with pride many years later after he went on to portray many nationalities through his many film roles around the world. In another interview clip that’s on view in the exhibit, we learn that this was one of his biggest motivations as an actor, to be able to become a Greek, Italian, Mexican, just about any nationality he wanted, on screen. It’s through this ability that he was able to surpass the stereotypical demeaning roles given to him at the beginning of his career and go on to be the first Mexican-American to win an Academy Award for Viva Zapata! (1952) alongside Marlon Brando and later a second for his role as Paul Gaugin alongside Kirk Douglas as Vincent Van Gogh in Lust for Life (1956).

Thinking of Quinn’s interest in becoming different people from around the world brings me to your question of a specific artwork that is representative of him and the sculpture titled Drifter stands out. Much like a literary archetype, we have a sculptural representation of a roaming figure who in someways could belong anywhere and in others doesn’t quite know where to call home. Quinn writes about walking the lonely deserts and sailing the seas with a sense of longing to feel whole, also coming to live in different places in hopes of filling this void. In Drifter, both the original olive wood carving (1978) and its slightly larger iteration in black marble (1980), our eyes are carried along smooth circular formations that overlap into each other, creating this sensation of reaching outside of ourselves in search of answers to the greater mysteries and then circling back inward again in a continuous inward and outward flow. There are no obvious signs of a face here, but I feel it strongly represents a part of Quinn that those of us on our own quests to feel whole can identify with. This is magnified when we add in the bicultural layer of those that may feel, and my apologies for the cliché but in this case it becomes very real, that they are from neither here nor there.

Anthony Quinn, Drifter, 1980, Black marble, 14 x 17 x 9 in, 35.6 x 43.2 x 22.9 cm, AQ2012.004.2), image courtesy Anthony Quinn Estate

In terms of eras, as you noted on our walkthrough together, many pieces selected for the exhibit date near or during the 1980s, Drifter included. At this point, Quinn was in his mid-sixties to mid-seventies and had already acted in over 150 movies! He continued acting throughout his entire life, of course, but his most seminal films were behind him at this point and he was ready to focus on his longtime calling to be a visual artist. It’s something he’d fostered since he was young, drawing portraits of people and taking classes when he could. He had even earned an opportunity to study architecture with Frank Lloyd Wright in high school. Katherine described Quinn as someone who was often compelled to draw what he saw. You’d easily find him sketching on the backs of restaurant menus or stopping whatever else he was doing to capture the magnificent landscape before him. But something happens around the 80s where he has the time and space to work more consistently and freely.

Now he is able to move past what I would consider to be studies in techniques into more experimentation where he really expands his use of color and scale and begins to define his own unique mark making. We can definitely notice influences from Joan Miró and Pablo Picasso, and I believe you also mentioned Georges Braque. But whether we’re looking at a lithograph, wooden assemblage or bronze cast from that time, there’s something that makes it uniquely Anthony Quinn, particularly in the eye imagery that we see repeated throughout the exhibit. It’s also important to note that he had his first solo exhibition in 1982 in Honolulu, where reportedly he sold every piece on display. This probably would have been very encouraging and meaningful to him because, up until that point, he’d only been the subject of an art exhibit at the MOMA in 1968. Titled The Career of an Actor, it featured 140 of his movie stills and pays beautiful homage to his true talents on screen, but I have an inkling Quinn would have preferred to be shown amongst the visual artists with his own creations.

Self-portraiture is the central theme of the exhibition, but there are many highly abstract works depicted through the various media Quinn utilized. How do you think abstraction represents “the self” in his artistic output, or for artists in general?

One of the most enjoyable parts of installing this show was grouping pieces together that connected visually somehow, whether through color palettes, composition, or repeated geometric forms. My hope was that any viewer with any level of art could feel the invitation to engage in their own visual explorations and make connections between artworks from different eras and even materials without feeling like they had to read anything or have any prior art history knowledge. In this exercise, to my surprise, progressions began to emerge where the drawing of what was very clearly a face with a boldly drawn eye morphs over the course of four drawings into a completely abstracted figure composed of overlapping outlines of triangles and circles going in all different directions. Or in another example, a small geometric horizontal drawing, when turned upright, becomes the side profile of a man’s face that we see in the two bronze versions and original wood carving of Maquette II.

Drawings by Anthony Quinn, image courtesy Yolanda Fauvet

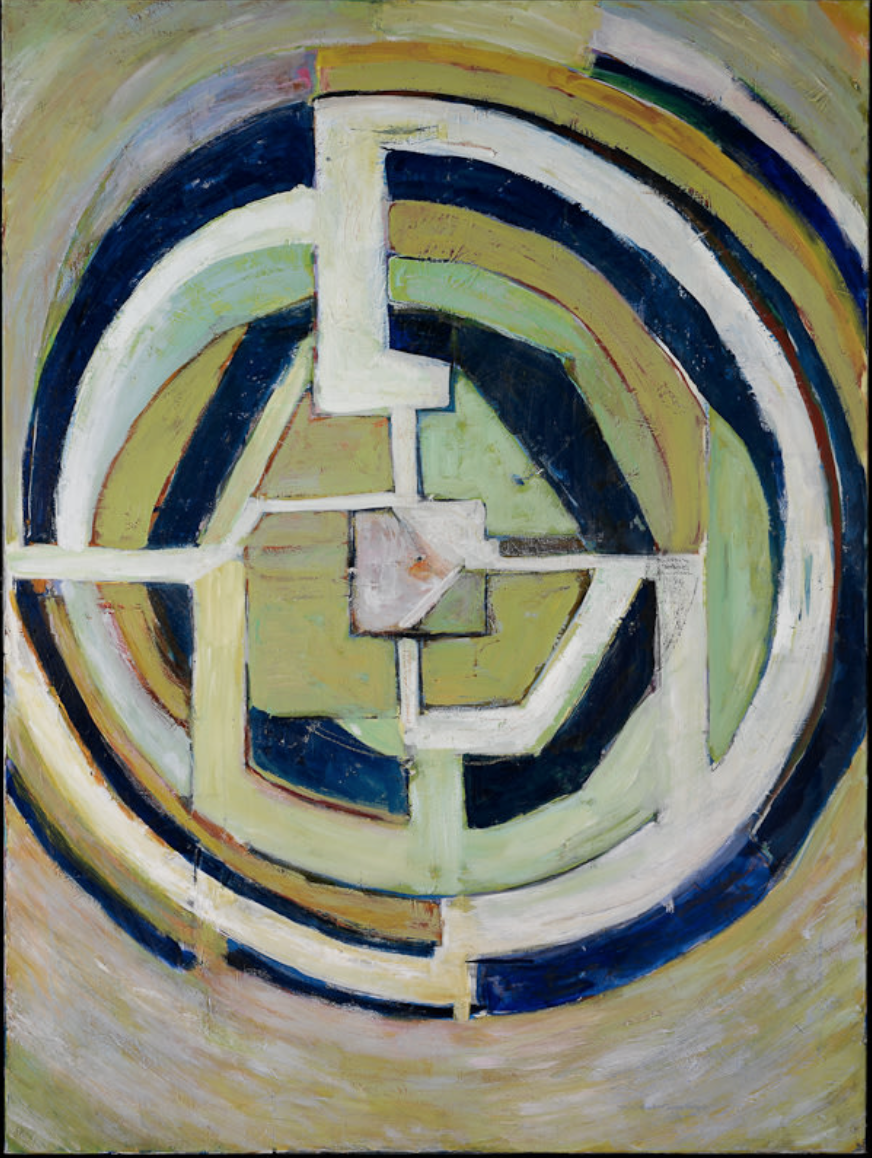

Up until the day of the opening, I was still finding semblances of faces where I hadn’t seen them before. This was partly because I had first experienced the artwork either online or in a dimly lit barn, so once the pieces were up in the gallery with professional lighting on them, many of the works seemed to take on a whole other life. The installation period was also when I truly had an opportunity to spend time with the work in person and really delve into the analysis of the question I had laid before me to explore Anthony Quinn’s self-portraiture and see what we could learn from it. So in this progression of unexpected portraits, I landed on a larger oil painting titled Circles with Interruptions (1994), which draws us into a mesmerizing pattern of concentric circles made up of varying bright shades of green, blue, yellow, and white.

Anthony Quinn, Circles with Interruptions, 1994, Oil on canvas, 48 x 36 in, 121.9 x 91.4 cm, (AQ2004.321), image courtesy Anthony Quinn Estate

Visually akin to a walking labyrinth, this painting might lead us to imagine an artist journeying towards the center of oneself, or at least in search of some kind of grounding. Although in this particular curving path towards self-reflection, we are taken off course with straight intersecting lines, most notably a thicker white line down the middle of the bottom half of the entire circular pattern. In the wooden assemblage to the right of the painting, we find a similar line that cuts the composition vertically and forms the outline of a face that is looking to the side. It is enmeshed with another face that is looking forward directly at the viewer. The dual perspective presented to us here is repeated in a few other pieces throughout the show and brings us back to Quinn’s dual identity as a Mexican-American. There is a richness of perspectives when growing up in a multicultural home that is often forgotten because we get caught up in the longing to belong to one side or to the other or a completely different place all together. So in terms of representing “the self,” abstraction and the celebration of all the different parts of us that make us unique was complementary to not only expressing his mixed cultural background, but also the many and varied characters he came to portray in his films. As I said in the inaugural remarks, we won’t find one single Anthony Quinn, but my hope is you will find yourself reflected in one of the many faces found in the exhibit, and I’d add that we can come to celebrate the many identities found within ourselves.

In that sense of refracted abstraction, we can easily identify his cubist influences, but in thinking back to the 1980s when he actually was making this work, we also had artists like Agnes Martin at the time that were turning their abstraction towards the land. In the way Martin painted meticulous repetitions of geometric shapes to portray the beauty and awe she experienced in the New Mexican landscapes where she lived, we can consider that Quinn created his Great Spirit lithographic series in his own response to the land and the spiritual inspiration he found in the wisdom shared by the Native peoples of the region. His mother and grandmother lived for a time with the Tarahumara in Northern Mexico, so it perhaps was with him all along, but in the intro of this artist book that houses the twenty lithographs, he wholeheartedly calls on the Spirit to guide him. So while at first glance we may not place Quinn alongside a minimalist artist like Martin, I think we can consider him within the broader category of artists that sought to capture their impressions of the West through abstract and geometric expressions, like Georgia O’Keefe and even Denver’s own Clyfford Still, whose artworks only add to the sense of pride we feel for this expansive and intrepid Western region.

I love that you consulted with artist friends who share the bicultural affinity with Quinn as part of your curatorial/research process. It’s easy to get tunnel vision when curating solo-artist exhibitions and become hyper-focused working with materials, writing etc that already exist rather than opening the topic up to other people who are exploring it for the first time just like you but still resonate with the work. If you had the opportunity to reimagine this exhibition as a group show, what other artists (both past and present) would you like to include? You mention visual connections with Picasso and Miró. . .

Oh wow, what a fun question! I especially appreciate it because one of my early sketches of the exhibit did include the first three artists I mentioned earlier (Adán, Ethan, and Viera). In the end it wasn’t possible to pursue the route of a group show, and perhaps I was being a little too ambitious for my first solo curatorial endeavor anyway. Certainly, I’m bummed it didn’t work out, but thinking of what a show could look like with these artists together has certainly planted a seed for future projects. Overall, I feel like the show fell into place as it needed to, as a solo exhibit, and will further situate Anthony Quinn as a visual artist in the public eye. Though perhaps an important next step would be to exhibit him alongside other artists and begin to look more thoughtfully as to where he falls within the larger art conversation.

As part of that, there’s also the question of are we looking at his artwork because he’s famous or does his artwork have the merit to stand on its own? I’m pretty sure Devon hinted at this when she brought up Sharon Stone during our pre-opening walkthrough together. It’s something I’ve been pondering since, and it’s an important question to raise for someone whose movie fame will follow him forever. In terms of the art I selected for this exhibition, there was a local relevancy to not only Quinn’s interest in the spiritual traditions of the region, but also in Colorado’s connections to his birthplace due to the large community of Chihuahenses living in the area. I also felt that his presence on Santa Fe Drive pays homage to the longtime Chicano community of the La Alma-Lincoln Park Neighborhood that houses the arts district. In terms of the art itself, ultimately it’s up to each person to decide what is art for them or not, but my personal —and very subjective— measure often lands on whether I feel the work is honest or not. And by golly, I can’t get through reading his entire Great Spirit introduction without choking up or look at The Breath of a Buffalo lithograph without a serene smile on my face. He bared his soul into his creative endeavors and, from what I’ve seen over the course of the show, people can feel it.

My consideration for showing Quinn alongside Adán, Ethan, and Viera wasn’t just because they all share varying degrees of Mexican or Latinx identity, but because of their shared renegade spirit with which they approach their artistic practices. When you live and breathe more than one cultural perspective, you’re bound to push the envelope somehow, and I wanted to celebrate that. In continuing to think of this hypothetical group show, I’d open it up to artists with roots in other parts of the world as well. Another Colorado friend, Tamar Miller, is doing some fascinating textile and text-based work, and Amanda Beard Garcia, the other artist friend I mentioned earlier, paints incredible murals and is fostering community among other Chinese-American creatives like herself with her project Lucky Knot Arts. If you start to think about it, you might know more multicultural people than you think! And by no means would the work in the show have to be about identity directly. It’d actually be rather refreshing and interesting to see what identity themes might naturally emerge without trying to force any particular message.

The thought of exhibiting Quinn with past artists calls to mind another one of his posthumous shows, The T’ang Horse, curated by Ysabel Pinyol. She paired his artwork with objects from his personal collection and we learn that Quinn also admired Henri Matisse. The show draws visual connections between Matisse’s Blue Nude series and Quinn’s own female nude sculptures, and in a similar vein, the style of British sculptor Henry Moore as well, whose nude painting also hangs in the Quinn home. Moore was one of Quinn’s favorites, and we can also see his influence in works like Quinn’s large figurative bronze sculpture titled Destroyed but not Defeated (which was not in the exhibit but his son Ryan writes about it here).

When considering all of Quinn’s influences, we can revel in someone who wasn’t afraid to try out the styles and techniques of the artists he admired. In the wooden assemblage portrait Fez, we see a starburst much like Miró’s in one eye, while the other eye feels reminiscent of the way Picasso would paint eyes with stylistic protruding lashes. In art school we may have been looked down upon for doing this, or at least I felt pressure to come up with my own style without even having learned all of my art technique ABC’s. But as one visitor said when looking at Fez, we can see the historical references are there, but Quinn’s approach feels open and free.

So there’s definitely more to be explored between Quinn and his influences, and a show like that could serve as a brief art history survey of sorts. In some ways, he could be the bridge for people who don’t frequent museums but might recognize him from his films and be inspired to go check out his art. I would be wary of bringing back the male gaze perspective with the nudes, though (unless we’d also have the space to talk about it with a critical lens). For the purposes of this exercise, I would rather focus on works that inspire imagination and storytelling perhaps.

Anthony Quinn, Dream Girl, 1982, Bronze with patina, 16 x 12 x 1 1/2 in, 40.6 x 30.5 x 3.8 cm, (AQ2012.002.5), image courtesy Anthony Quinn Estate

Thinking back to the show, I was drawn to Quinn’s use of blue, the most striking being the all-blue version of Dream Girl. That piece is more fantastical than some of his other portraits, and the blue makes it magical. We can also find it in more unexpected places, like in the highlights of his mother’s hair in the large portrait of her in the Unfulfilled Promises triptych, or even in his own hair as Archbishop Kiril and Barabbas. There was also a vivid blue version of the bronze Song of Zorba that I wanted to include in the movie portraits section, but we couldn’t get a base for it in time. Once you start looking for blue in Quinn’s work, it appears even in landscapes and several of his portrait sketches. Matisse had no lack of blue paintings and Picasso’s blue period comes to mind as well. I’d even include some blue paintings from Van Gogh and Paul Gaugin’s blue trees, as surely we could speculate he may have been influenced by them while working on Lust for Life. Even Henry Moore has some metal sculptures with a blueish patina that I have to think influenced Quinn’s own experimentation of patinas just as perhaps Joan Miró might have inspired him to explore lithography. I’m not sure if I’d be committing some sort of art historical or curatorial crime, but it’d sure be a grand and beautiful show to put together.

Anthony Quinn: What am I? ¿Qué soy?, installation view, image courtesy of Museo de las Americas

On a more personal topic, you spent several years living in Mexico City where you studied in a literary translation program and have since developed this into a profession steeped in community and creativity. Please share more about what you do and what current projects you have!

Two major projects got their ground during my time in Mexico: my translation business, LATERAL, and the literary translation collective that I’m a part of, FALSOS AMIGOS (a play on the nickname for false cognates in Spanish). We’re based in Mexico City and the eight of us got together after graduating from our translation program at UNAM. Our main mission has been to promote collaborative translation processes, mainly by working intimately together on projects, but we’ve started to teach workshops as well. We also use our instagram account to explore different translation issues, techniques, and practices with the greater public. Some of the most compelling posts have been exploring the ways in which translation appears in our everyday lives and getting to hear other people’s thoughts on the subject.

Pretty much as soon as we decided to form the collective we dove right into a large undertaking that carried us through the pandemic and keeps us busy still today. It was our collective mate Dian Barberena-Jonas that brought up the idea of translating an anthology of science fiction short stories written by women that had just been published at the time. Dian’s a huge sci-fi buff and write’s their own science fiction as well, but the rest of us were a little intimidated by the idea of working with a genre we weren’t as familiar with. But as we read the stories we quickly connected to the very personal female experiences and societal issues that were being explored through these fictitious or futuristic scenarios, and so we took it on. We were excited to see the ways in which women have always been at the forefront of the genre, and it’s been pretty rewarding to have our translations of the stories be received amongst science fiction and writing communities throughout Mexico.

Edited by Lisa Yaszek, the full title in English is The Future is Female! 25 Classic Science Fiction Stories by Women: From Pulp Fiction to Ursula K. Le Guin. For the Spanish version, we worked with the publisher Almadía and divided the anthology into three smaller tomes: Mundos alternos, Retro futurismos, and Futuros distópicos. I believe all three are out in Spain and the second, Retro futurismos, just hit the shelves in Mexico. Actually, I’ll be going to Irapuato, Guanajuato, to present the book with a couple other collective mates in mid-September. We’re also in talks with the publisher to begin working on the second volume that Yaszek put out last year. The first volume chronicles early stories from the 1920s through the 1960s and the second focuses on the expansion of the genre throughout the 70s, and boy does it pack a rebellious punch.

As for my other project, another collective mate Paulina H. Marroquín and I have been working on translations together for over five years and this collaboration has morphed into a small business called LATERAL. It’s based in the US and we mainly work with art-related texts, for example, translating articles for the Texas art magazine Glasstire and translating exhibition texts with Elyse Gonzalez over at Ruby City. We have also been working on social justice related projects with the Othering & Belonging Institute (OBI) over the past few years. Recently, we also delved into the world of translating in code with a few interactive training projects working with artist and program manager Adrián Aguirre at New Mexico State University. This past spring I also co-lead a bilingual mural ambassador program alongside Amanda and the Punto Urban Art Museum for the residents of the Punto Neighborhood in mine and my husband Saniego’s new home of Salem, Massachusetts. Sometimes Paulina and I will also pull in other FALSOS AMIGOS collective members to help out on LATERAL projects as well, so between both groups it’s a very fluid mix of art, literature, friendship, exploring new translation approaches, and pushing each other professionally.

I also like that you mention community in your question because many of the clients I work with now are people I met through the art world in Mexico City and Denver. Plus, translation, or at least Spanish, has always gone hand in hand with art for me. I’d say it’s my visits to Mexico as a child and into adulthood that inspired me to study art in the first place. Later in college I’d find myself in situations where my Spanish skills were needed, as rough as they were, to interpret for visiting artists (most memorably Regina José Galindo whose kindness still warms my heart). The need for Spanish also came up in collaborative projects with M12, like with Campito, where we interviewed a South American migrant worker about the sheepherding routes he would take through rural Colorado. My Spanish wasn’t to the level it is now (at that point I’d only really spoken Spanish at home and with family), but as it happens with most everyday translation scenarios, I was the person who knew the most and was willing to help, and somehow we got through.

Speaking of community, I have to say that Devon hiring me to translate the Dikeou Collection’s cellphone tour during my first months living in Mexico in 2016 put me on the path I’m on now. It was one of the first times I’d really been hired to do that kind of work. I enjoyed it but realized I needed to expand my skillset bigtime. I immediately started studying Spanish formally at UNAM, which later lead me to the translation program there as well. I know I’m supposed to be talking about current and future projects, but I can’t help reflecting on the past at the same time. Especially because this Anthony Quinn show has been like a returning to home of sorts. Besides the fact that I’ve literally been staying with my Mom while in Colorado, my first job out of college was at Museo de las Américas and never had I imagined I’d be curating a show there several years later. It’s been like a big warm hug being back in the familiarity of Denver and the wonderful people here that I’ve gotten to call my friends over the years.

So, thank you, Hayley, for all of these thought-provoking questions and giving me the space to reflect on all that’s happened. Working in translation has taken me to some unexpected places and we’ll see where things go from here. For now I didn’t realize there’d be so many social engagements following the opening, so I’m eager to return to the quiet of my desk and get caught up on all the translations I owe!

Anthony Quinn: What am I? ¿Qué soy? is on view at Museo de las Americas in Denver through September 22, 2024