Simon Bill seated in front of his signature oval paintings. Image courtesy of the artist.

English painter Simon Bill has a reputation as an “artist’s artist.” His work, which consists almost exclusively of large oval paintings on MDF board, is collected by a loyal base of fellow British artists who see the depth of consciousness and humor embedded within their often grimy surfaces composed of corn kernels, leaves, and floor varnish. The ovals are like portals into the infinite curiosity and complexity of Bill’s mind in which he pushes himself to make each one completely unlike any other that he made before. These works spring from a psychological interest in visual perception, a field he has studied in depth academically.

In zingmagazine 24, Bill flexes his skills as a writer with a short-story titled “How a Man Schall Be Armyed” about an artist who invests a good deal of money on a custom suit of armor and wears for the first time to a private viewing at a gallery. Bill’s writing integrates such an illogical scenario with real life situations and outcomes so seamlessly that it seems like he wrote this story based off personal experience. I even had to double-check to confirm that it was fiction. Bill’s psychological understanding of perception comes through in his writing and visual art, giving him the ability to convince his reader/viewer of the veracity behind the most outlandish of his creations.

Interview by Hayley Richardson

Your project in zingmagazine 24 is a fictional short story that is hilarious and absurd yet written in a very believable manner. The accompanying images are also funny in this context but relevant and interesting for their obscure historical value. Can you share some footnotes to this story and how you came up with it? Did the pictures inspire the text in some way?

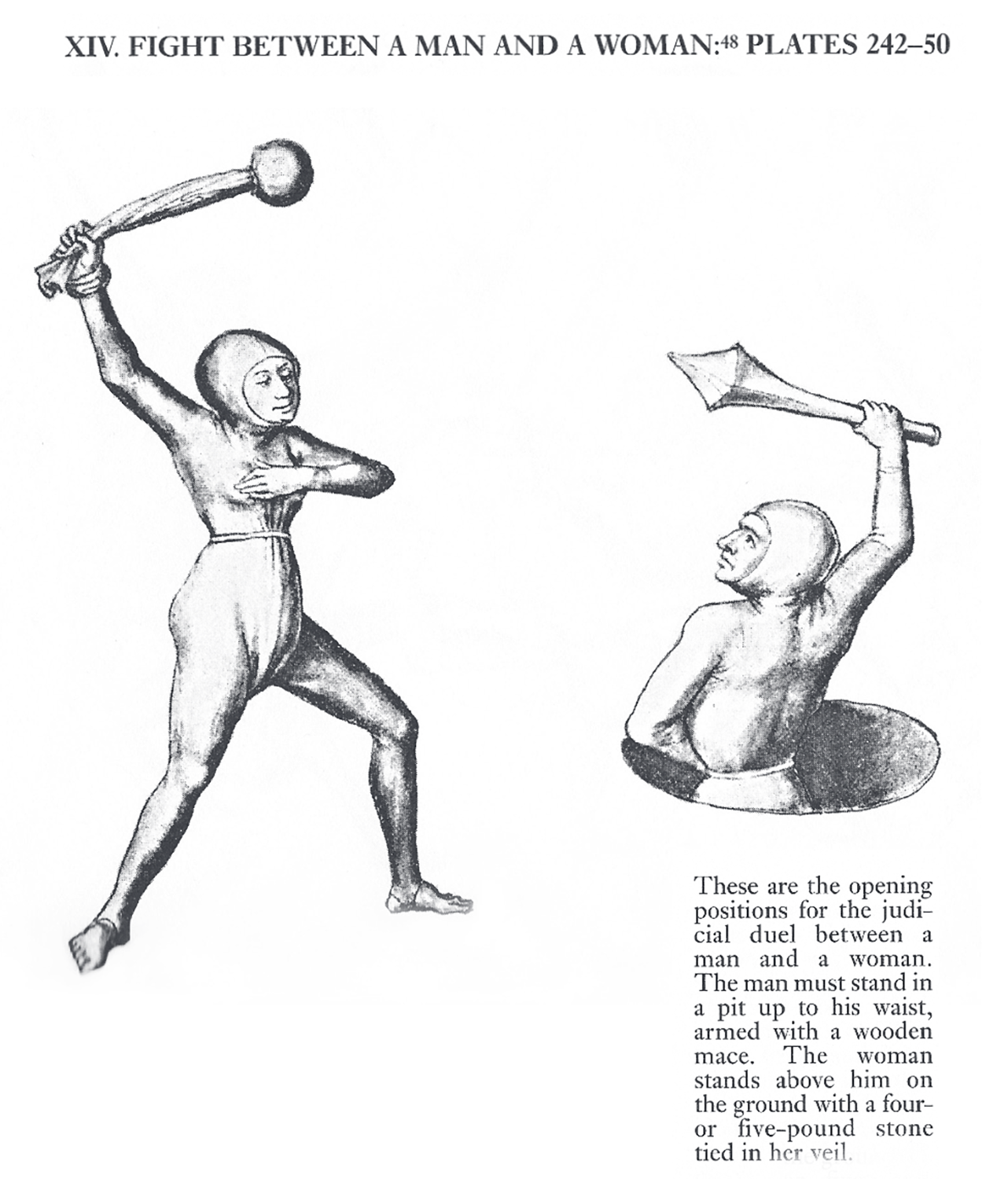

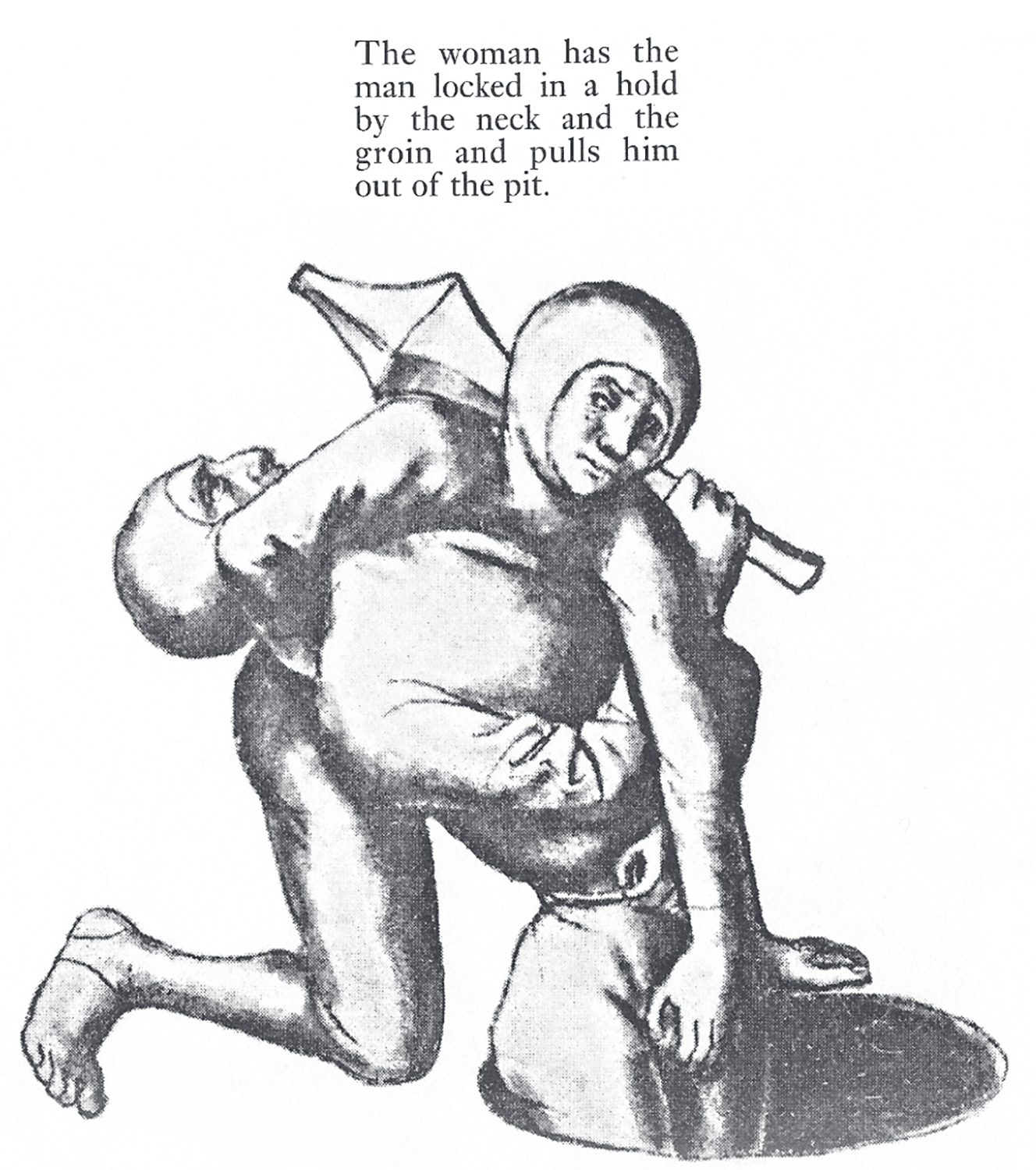

I attached those pictures to the text especially for this ZING publication of it (it has been published once before, years ago, in an anthology called FROZEN TEARS 2003—pub. Article Press, ed. John Russell). But they are of course connected. The suit of armour described in the story is roughly contemporaneous with the pictures. They come from one of the German ‘fechtbucher’ (fight books) of the mid 15th century—basically martial arts manuals. And I chose them because they are so odd. They show a judicial duel between a man and a woman. The loser gets put to death, or they do if they haven’t been killed already in the fight.

This short story was my first real go at writing fiction. What gave me the idea was an event at which a battle from the Wars of the Roses was reenacted, and afterwards I saw a man in full armour coming out of one those portable toilets. That prompted, more or less naturally, some speculation about all the other contemporary things you could do whilst dressed like that. And since I am an artist, and have at times felt that I was doing almost nothing but go to private views, I wrote it about that.

The theme of the improbability of some actual things, like, for instance, the art world, is something that crops up regularly in my fiction. I am very interested in the strangeness of real things (and I find the weirdness of invented or fantastical worlds completely pointless). The terrific implausibility of these real things, which tends not to be evident to those of us who are involved in them, is made salient by having two such things in one context; one story—here it’s medieval reenacting as a hobby, and the contemporary art world.

A page from Simon Bill’s project, “How a Man Schall Be Armyed,” in zingmagazine issue 24. Drawings are reproductions from 15th century originals by an unknown artist commissioned by Hans Talhoffer.

A 2004 article from Modern Painters says that the first art show you ever saw was Arms & Armour at the Wallace Collection in 1964. I can’t help but wonder if that experience has any connection with How a Man Schall Be Armyed and your interest in medieval European combat. Were you always interested in art and history growing up?

I have been interested in a great many extremely diverse subjects over the years, and those have been two. Others include neuroscience, BIBA (the shop), philosophy, comedy (I used to collect records by e.g. Bob Newhart, Lenny Bruce, Monty Python), swords, music (Bach and the Butthole Surfers, and I’m very interested in the shoegazing revival), and cooking. And other things . . .

Like in How a Man Schall Be Armyed, your book Brains (2011) also features an anonymous artist as the narrator/main character. Is this individual, in either story, sort of an amalgamation of various personalities from the art world, or reflect aspects of your own personality?

I know some writers of fiction claim that their characters, once created, are self determining, so that the author magically loses control, but if that were true more characters in books would just sit around eating pistachio nuts.

All the characters in my book (with the exception of some very minor ones) are amalgams or composites with various sources. They are drawn from other people and myself, plus a great deal about them is, of course, made up—it’s fiction.

The central character of a book is the one least free to be, as it were, themselves, because they are the character most obliged to do what the book needs them to. The unnamed protagonist of BRAINS has a set of characteristics I find funny or interesting, and is seen bringing those characteristics to a series of situations which I also find funny or interesting. It’s not meant to be naturalistic in any stylistic way, but as it happens that is more or less the way actual characters, real people that is, are formed. We are dealt a hand, somehow, and then we play it.

Lucky Jim, installation view, BALTIC Centre for Contemporary Art, 2014. Image courtesy of the museum.

Last year your solo exhibition, Lucky Jim, at the Baltic Art Center featured more than thirty of your oval paintings from 1999 to 2014. Every piece is composed with different materials and in varying styles, the only consistency being the shape of the canvas. Is there an underlying subject matter or theme that unifies these works?

As soon as I spot a characteristic common to all my oval paintings I do one that doesn’t have it. The point is to do a potentially infinite series with no one thing in common, so, in the context of the whole body of work, what gives each work its identity is just the fact of it not being any of the others. The paintings are defined negatively. This means you can’t have a typical example of my work. And this may be why so few collectors ever buy them. I didn’t think that through very well, did I.

A lot of those paintings have suffered a weird fate. The dealer who represented me, a guy in LA called Patrick Painter, has gone insane, and has put about sixty of them in a storage place in Compton. He wouldn’t even release them for the BALTIC show. I’m expecting to see my work on Storage Wars any day.

I read that you are currently pursuing a PhD on art and the neuropsychology of visual perception. Has research in this field influenced your own art or changed the way you experience it?

It hasn’t changed my art or changed the way I experience it. But I want to better understand how I experience it. There has been a thread within art theory that brought the psychology of visual perception to bear upon the understanding of art. I’m thinking especially of Rudolf Arnheim. Art theorists have forgotten about this, because of their strong emphasis on ‘Critical Theory’ and a culture critical approach. I reckon they are really missing out. The neuropsychology of visual perception has come on in leaps and bounds since Arnheim, and art theory folk have just ignored it. Too sciencey I guess.

Art, writing, and neurological studies all tie together in your practice. Do you have a specific goal in combining all these pursuits? Does one area serve as the dominating or guiding force in this scheme?

I’m an old fashioned polymath.

These days images seem to be superseding words as our primary form of communication. In that same article from Modern Painters you state, “language is slow to adapt to developments in art,” that “writers are stuck for words.” Being both a writer and an artist, do you often find yourself faced with this conundrum? Does criticism of contemporary art have value if its language is supposedly inadequate?

I haven’t got a primary form of communication because they are each good at doing different things. This is why I have no time for those mock innovations in contemporary art that consist only of replacing an existing medium with another one that already existed elsewhere in our culture. So, for example, ‘text based’ art is no innovation because, surprise surprise, people were already writing things down anyhow before artists came along and decided it was a new art form.

And there’s ‘time based’ art isn’t there. A characteristic unique to visual art has been that, while the other creative media such as music, literature and theatre, were all time based, painting and sculpture were not. So making visual art ‘time based’ adds nothing we didn’t have plenty of already. It’s actually a net loss.

You are often associated with the Young British Artists. Do you still feel an affinity with this movement/group?

We have very little in common as artists, but I do know a lot of them. That’s the whole of the association with them really. We have been in the same rooms as each other, sometimes. Plus my daughter and Gavin Turk’s daughter are best friends.

A page from Simon Bill’s project, “How a Man Schall Be Armyed,” in zingmagazine issue 24. Drawings are reproductions from 15th century originals by an unknown artist commissioned by Hans Talhoffer.

What are some of your favorite galleries/museums/art venues? Any recent exhibitions that really caught your attention?

I love museums, although they have all been done up in recent years, so there aren’t many with that neglected, spooky, feel I used to enjoy. Most of the ones I know well are in London, but the Metropolitan in New York is amazing. You mentioned the Wallace Collection, and that’s still a favourite. The Imperial War Museum (I often think contemporary artists need to look at more things other than contemporary art). The Barbican, near where I live, has OK art shows and an amazing library. The V&A is great. In fact all the main ones in London, The British Museum, The Natural History Museum and the Science Museum, are all great. I would also recommend The Royal Armouries in Leeds, and the BALTIC centre for contemporary art in Gateshead. My friend Brian Griffiths has a good show on there now. The Museum of London has a display of knapped flints I really like.

Do you have any upcoming shows or projects you can share?

My novel ARTIST IN RESIDENCE comes out in May 2016 (published by Sort of Books and distributed by Faber). I’m planning a painting show to coincide with that. Not oval paintings. They will be miniatures, painted in oil, on copper plates the size of a credit card.