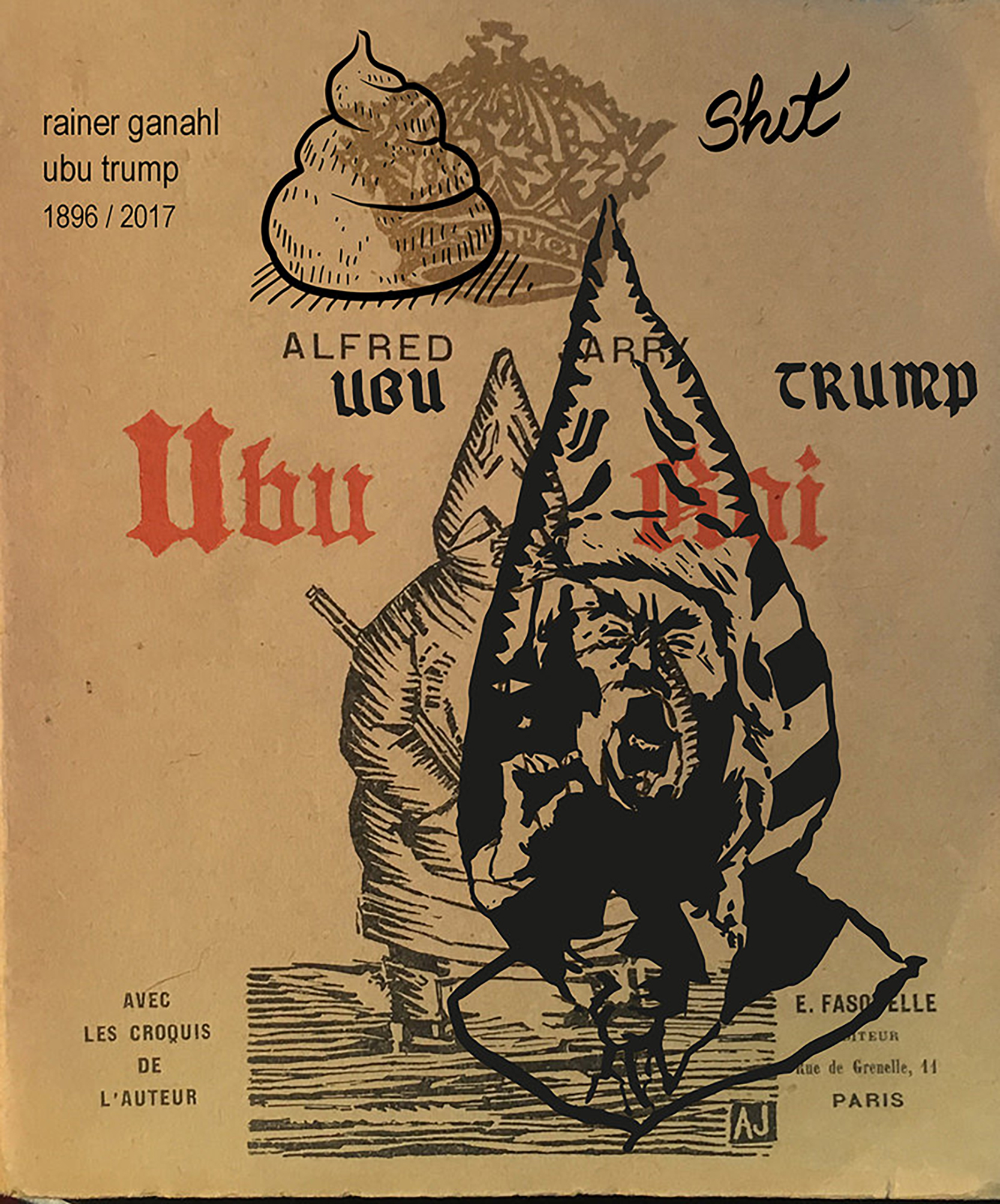

On Friday, December 1st, 2017 Rainer Ganahl’s new play Ubu Trump premiered at the unlikely locale of Daniels Wilhelmina Funeral Home in central Harlem. Inspired by the life and writings of Alfred Jarry and following up on Ganahl’s previous text Ubu Lenin, his new work Ubu Trump is a postmodern blend of original text and derivation set in Warsaw/Washington D.C. and starring Donald Trump in the role of Jarry’s King Ubu, along with appearances by Ivanka Trump, Jared Kushner, and Vladimir Putin. The performance can be watched in full here.

Interview by Linda Norden

Tell me a little bit about Alfred Jarry’s Ubu. Why did you chose to rewrite him?

Alfred Jarry was a tragi-comic modernist figure, the quintessential poet-artist who was also a self-destructive loser and died at just 34 in 1907. Yet he managed to influence literature and art for a century to come. Jarry did not really leave any oeuvre, but a bunch of writings, text fragments, plays and graphic works that were all embedded in a drug and alcohol-driven universe of crazy anecdotes, love stories, including with Oscar Wilde, and personal recklessness. His Ubu Roi (King Ubu) was not even written by him alone, but co-written with two high school friends who thought of it as a literary diatribe against an annoying teacher. Jarry ran with it from his native little French town and made it into a literary scandal in Paris. He kept changing it and changing it and produced numerous versions. Jarry clearly stylized himself as an Ubu-esque character, took on weird linguistic and behavioral mannerisms and didn’t refrain even from threatening and shooting at his critics with a pistol he carried with him called “bulldog.” King Ubu, Papa Ubu, Ubu Cocu (Ubu Cuckolded), Ubu Enchaîné (Ubu in Chains) and other versions produced by Jarry symbolized a narcistically damaged, insecure dictator who accumulated as much power as he could by any means and terrorized everybody. This all happened just before the WWI, which was essentially a colonialist war. During that war, in Zurich, Jarry’s Ubu Roi was presented at Cabaret Voltaire, which inspired me to revist this piece for my Dada Lenin project, since it can be assumed that Lenin himself—who lived opposite the Cabaret at Spiegelgasse—attended the performance. So after having already rewritten this theater play for a Ubu Lenin, it became quickly clear that I also must rewrite it as Ubu Trump, since this president resembles Ubu King in many many ways: vulgar, loud, insecure, narcissistic, brutal, and with disastrous judgment that will bring defeat upon his people and himself.

Why stage the Ubu Lenin play in a funeral home in Harlem?

This play is independent of any particular presentation or site. It could be read or presented between friends at a dinner table, in bed with a lover or at a theater.

But given the fact that I’ve been living in central Harlem for more than two decades, and that I’m surrounded by morgues and churches, I started to take this option of presentation into account. I also enjoy finding locations myself. Thanks to my notary public, who runs an actual funeral home, I started to become more curious and familiar with these somehow scary, taboo places. We do not want to have anything to do with a morgue since that represents the last transitory stop on our journeys and when we enter it’s usually for a sad, tragic last moment.

I realized this funeral home could not only house a public that is mourning a private loss, but also a frustrated public that’s suffering a collective political loss. Better than churches, funeral parlors do not relate to any religious belief system. Ubu Trump as a play is very bloody with themes of murder, torture and war that build on a core struggle for power.

I feel like there’s a large part of the community your re-purposing—your “enterprising” use of the funeral home—might offend. People who believe in the sanctity of death. But I was very taken by this performance in that space. I’m often suspicious when a spontaneous, inspired idea becomes fetishized or over-extended. But one of the things I like best in your work is the way you find such inspired sites for each project, as something takes form in response to the very specific circumstances you respond to so keenly in your day-to-day life. Your sites always feel integrally bound up in the issues and questions they assert, because you look at the neighborhoods and communities you live in so topologically. I like thinking of your Ubu Trump project as having something to do with the way war takes form.

I owe the entire structure to Alfred Jarry’s original Ubu King, which brilliantly anticipated the series of dictators we had to endure during the 20th century, when war was omnipresent. It is stunning how this current president has representatives tell troops in the field that war is imminent while he simultaneously shrinks his diplomatic core down to almost nothing. After all, diplomacy’s function is to use means other than war.

How did you decide on characters, besides Trump. And did you know where you wanted play to end before you began?

There is a given textual structure that I respected and did not change the positioning of certain material, which itself seems to have elements lifted from Shakespeare and others. The main characters in Jarry’s version are King Ubu; his scheming wife, mostly referred to as Mama Ubu; and King Wenceslas on the other side. Therefore, Ubu Trump is repopulated with Ubu Trump, Ubu Ivanka, the King and Queen Wenceslas and their daughter Chelsea. We also have Putin, Jared Kushner, Michael Flynn, and other figures from the current administration. I also give prominence to contemporary sexual predators such as Anthony Weiner and Roy Moore.

Were you modeling your text closely or broadly on Jarry or did you do a lot of the writing yourself?

Many of the newly replaced and introduced protagonists come with lines I modified and adapted for the scenes. It is remarkable how the current president and his advisers are jamming the media stream with vulgarities and falsehoods. We are currently witnessing how public discourse that was once mediated by mainstream news sources has been replaced by social media and fake news sites. Therefore it’s not very difficult to scan for material worthy of Ubu. Jarry’s premonitory brilliance becomes more and more apparent through these boundless autocratic, proto-fascist, self-propagating revolutionaries and their rampaging disregard for the world. Make America Ubu Again. Somehow I had the feeling that I didn’t write anything at all, but merely updated it, resynchronized it with our current presidential tropes and tuned it to our attention economy of followers, sharers and likers.

I’d really love to hear what you were after in each of the characters you shaped for Ubu Trump. Would be great to hear how a certain comment or speech conveyed your sense of behavior and character.

Ubu Trump is here really a combination of Jarry’s madman Ubu King and Donald Trump’s publicly displayed idiosyncrasies, which my particular exaggerations and usage render slightly more farcical. I wanted to really decontextualize our president’s shameless, partisan, and self-serving political actionism by placing into literary-political satire. After all, reading the New York Times on Trump’s spontaneous, chaotic decision making and sloganeering already reads like Jarry. And sometimes the reality of our political time seems more authentically captured by comedians than by theory.

I was struck on the night of the Ubu Trump performance by the difference between the performance of the play, which felt more like a declaration, or demonstration, than a question, and by the terrifically curated gathering of art, by so many of your friends and peers, in your home, which you seemed to share as if asking “How about this?” In both cases, you seemed genuinely surprised by the size of the audience or attending group, as if these were both projects you did for yourself. But I’m genuinely curious: who do you think you do the work you do for?

I fully agree with you. Repurposing sensitive spaces can be highly problematic and easily go wrong. I try to be very sensitive and was choosing this site also because of its precarious and meaningful role in society. In Austria, where I grew up, they keep death out of view and when I first saw an actual friend on her final open display in Brooklyn, after a suicide, I was traumatized—even more so since I had never seen a dead person before. Now, death in Harlem is pervasive, given the explosive mix of racism, the high concentration of poor people in sometimes substandard living conditions, police bias, and more. But that already makes us enter the very essence of Ubu Trump, a play where horrific governance creates misery and war.

I think in both cases—my friends’ artworks in my house and this performance—I do it for myself as part of a public and imagined community. Some of my circle of friends and imagined friends are not even alive, and I might have missed them by a decade or a century or a continent. I count myself as part of my own community and I sometimes project myself onto others who are there or who I wish would be there.

Are there any more Ubu Trump presentations planned?

Yes. A similar version will be staged in Berlin in January 2018 and another one in Mexico City in April. That one will appear exactly 50 years after the famously problematic Mexican Olympic games of 1968, which resulted in the deaths of hundreds of street protesters. Mexicans, Trump’s wall and the ghost of the student massacre will all be making guest appearances in that iteration of Ubu Trump. I am also working on yet another version to present in London, where curator Saim Demican and I will reorient ourselves with Werner Fassbinder’s version of Ubu Roi, which he presented at the Anti-Theater in August of 1968.