Rainer Ganahl is a conceptual artist and lover of Marxist theory, who works in mediums ranging from film to political Manifesto. He often records and makes objects of events like educational seminars, Marxist fashion shows and imitation of the life of writer Alfred Jarry. Simultaneously student and teacher, his work portrays the intersections of politics, education, language, class, history and fashion. His artistic practice is never solitary, but rather relies on collaboration and group involvement to draw connections between audience and performer, brand and consumer. Ganahl has published numerous books including Reading Karl Marx, Ortssprache—Local Language, Educational Complex, and Please, Write Your Opinions of U.S. Politics. His work has been featured in zingmagazine five times including Basic Russian (Issue 2), seminars/lectures (s/l) (Issue 15), Iraq Dialogs (Issue 19), and FONTANAGANAHL—Concept of Rage: 1960s/2010s (Issue 23). I spoke with him about his project Hermes-Marx, which is featured in Issue 24 and resides at Dikeou Pop-Up: Colfax in Denver, Colorado. In our correspondence via email, Ganahl exclaimed “MY ENGLISH SUCKS”, which really isn’t true: Rainer Ganahl writes with an elegant fire.

Interview by Liana Woodward

How did you first become interested in the works of Karl Marx?

As a teenager I came across Karl Marx’s early writings published in German in a beautiful light blue hardcover volume that was handy and lovely. His thinking changed my life thought. His writing has little to do with what he [eventually] came to signify, but rather with historical materialism as a philosophical position in regard to religion, to society, and to work.

How can we understand the art world, and the creation of art objects, through a lens of historical materialism? Where does Marx’s political philosophy intersect with art?

The short and cynical, but truth-carrying answer would be a classical one: follow the money. A more melodic or pastoral one could be: go with the pleasures and anxieties of people. The drives and truth-techniques that they develop to domesticate, cultivate, or differentiate their senses and what-have-yous. People are creatures who create and depend on tools to handle their imaginings, ghosts, fire and fears, to fight off enemies, hunger and cold, to produce pleasure and excess, fun and abundance, to fill in the gaps between misery and disease, shortage and lack.

I tell my kids that stories are made by women and men, not by some god. Ghosts and gods are nothing but stories we use to deal with fears and desires of bad and good monsters, beauty and fairies, power and its opposite, gain and abundance. In the realm of storytelling and demonstrative silence (organized noise or haptic enjoyment for the ears and eyes) we approach what later will be commodified as art.

That is Marx for pre-K and kindergarten and can produce satisfaction and arguments until graduation with curators and wealth managers, portfolio geeks, and speculators. Hence, Marx for red points and red tapes, for high heels, private jets and Basel or Hong Kong free-port storage access. Marx is really the pre-inventor of the Swiss Army Knife for philosophy and polyglot money. Viva Marx.

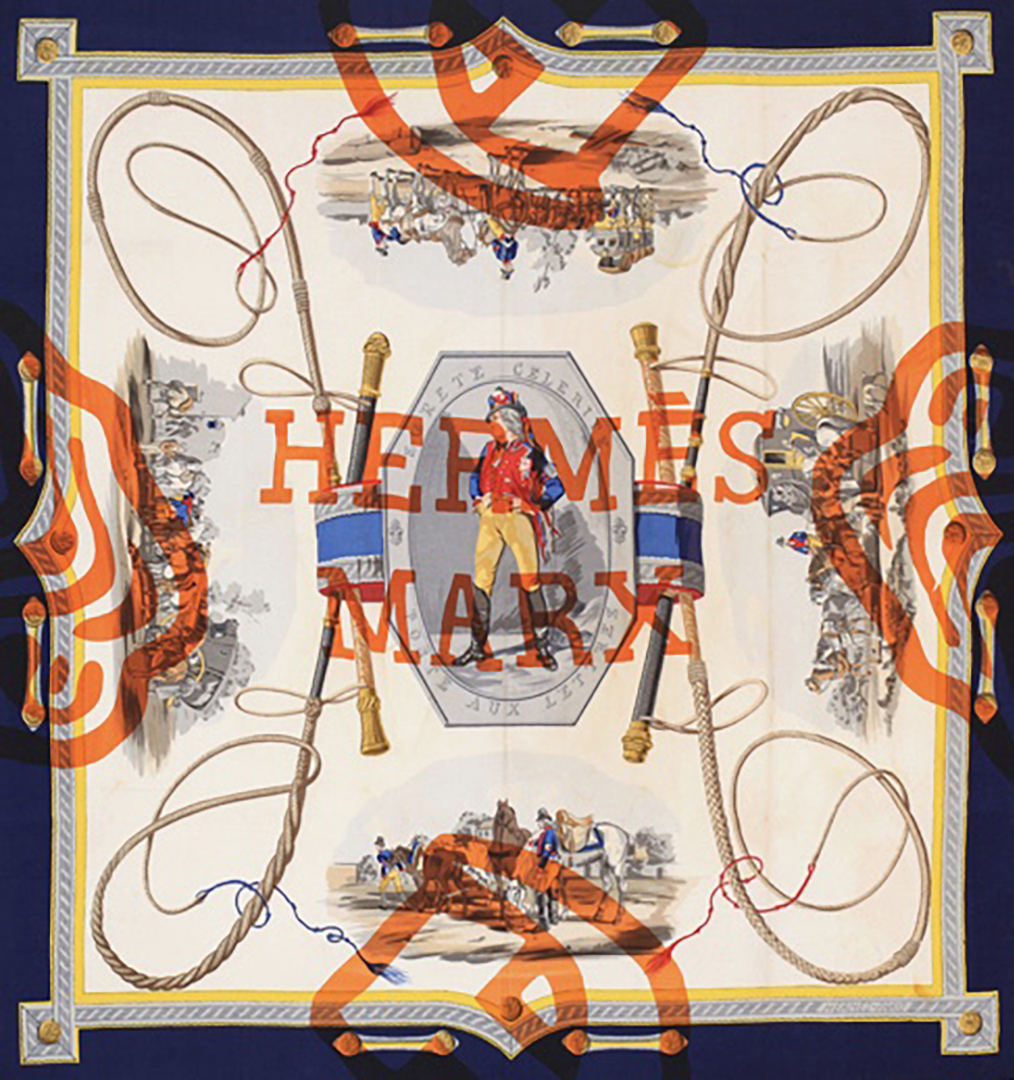

Speaking of money, can you talk a bit about how your project Hermes Marx? By silk-screening your own Marxist imagery onto the scarves you are in some way destroying their value as high-end exchange commodities. Is there some intrinsic or artistic value that you add to the scarves?

Well, as an artist I have to assign artistic value to my art works. If I don’t do it nobody else does. So yes, I do assign my ‘destruction’ or my ‘intervention’ a precondition to render a consumer object into my art. I acknowledge that the classical exchange value of the Hermes scarf is wasted with my design silk-screened over the original foulard but by doing so, I defend it as my proposed art work.

How do you think the magazine format changes how Hermes Marx is perceived by the viewer? Do you think the image of the object holds the same power or value that the actual object does?

No, it is not the same at all—but some art works photograph better than others and therefor what you see is not what you get—it’s either better or worse but both legitimate.

The scarves that you used for Hermes Marx have designs related to colonialism. How do the symbols and words you silk screened onto the scarves interact with that imagery?

There are two words I don’t change: HERMES MARX in reference to the corporate reference of the French foulard Hermes Paris. I consider the name Marx to signify an attempt to envision, demand, claim, enact, and fight for a larger more even kind of justice that is not only defined and reserved for the powerful and privileged. So all I did was exchange PARIS, the capital of the 19th century and French-speaking colonialism, with the name of a German philosopher who presented the world with the most radical ideas of justice of his time. Let me also point out that Marxism came with the symbol of the overlay of a hammer and sickle and the fist which is a part of the design that I print over the original French silk scarves.

Is there something in particular about Hermes Paris as a company that made you want to use their products for this project? Why not some other well-known designer?

Hermes belongs to one of the most prestigious fashion and accessory houses. They are know for making everything themselves including the production of silk and the colors that enter the product. It is truly beautiful and not necessarily cheap which makes if more coveted and impermeable to sales and other price dumping. Somehow they seemed to anachronistic even in the way they run their family biz and I think the company is still largely controlled by the family. I myself collect these foulards and truly love them.