Olav Westphalen performing “Even Steven,” at Index, Stockholm, photo: Santiago Mostyn

Olav Westphalen describes himself as a “provincial artist without a province.” For some this may seem like a challenging position, but he maintains it just fine by having an open mind and a sense of humor. Using cartoons and comedy as his main vehicles for creative expression, he is able to transcend cultural barriers and address serious topics in thoughtful ways that will make you laugh. Inspiration is found within the intricate web that connects art and entertainment, creativity and industry, and people and places, which enables him to forge peculiar collaborations with professional dancers and experimental musicians or pull off stunts like burning tires in the Arctic. Westphalen’s project in zingmagazine 24 draws attention to the absurdity that lurks just beneath the surface of the ordinary, and serves as a handy tool for artists and non-artists alike to grasp the power of this absurdity. He and I chatted via email about his creative influences, the art market, polar research missions, and bad jokes.

Interview by Hayley Richardson

Your project in zing, “A junkie in the forest doing things the hard way,” was initially an exhibition of the same title at Galerie Georges-Philippe & Nathalie Vallois. It is interesting to compare the images on a page-by-page basis in the magazine to that of installation photos from the gallery. Can you talk about how your work fluctuates/relates to the presentation context?

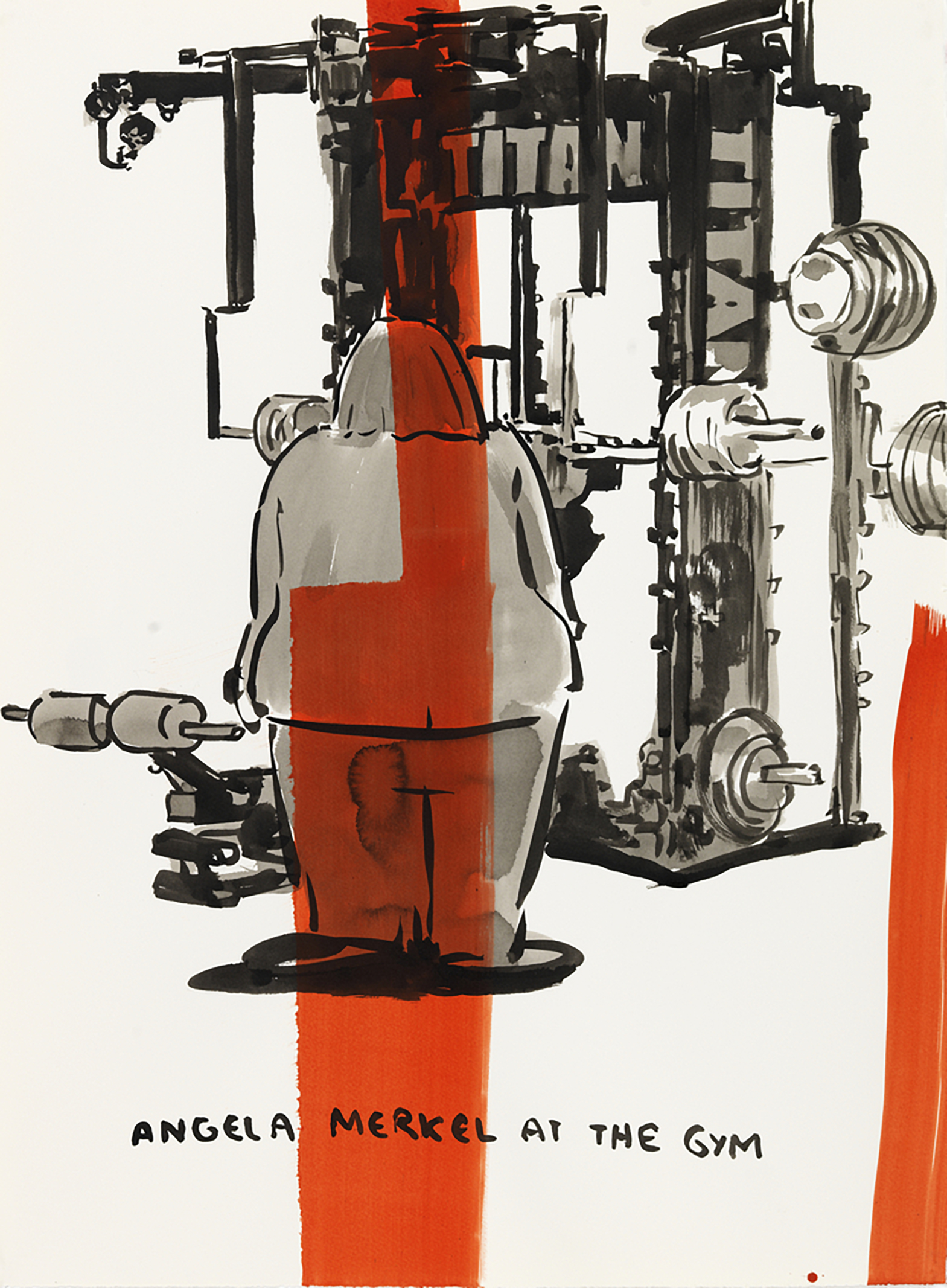

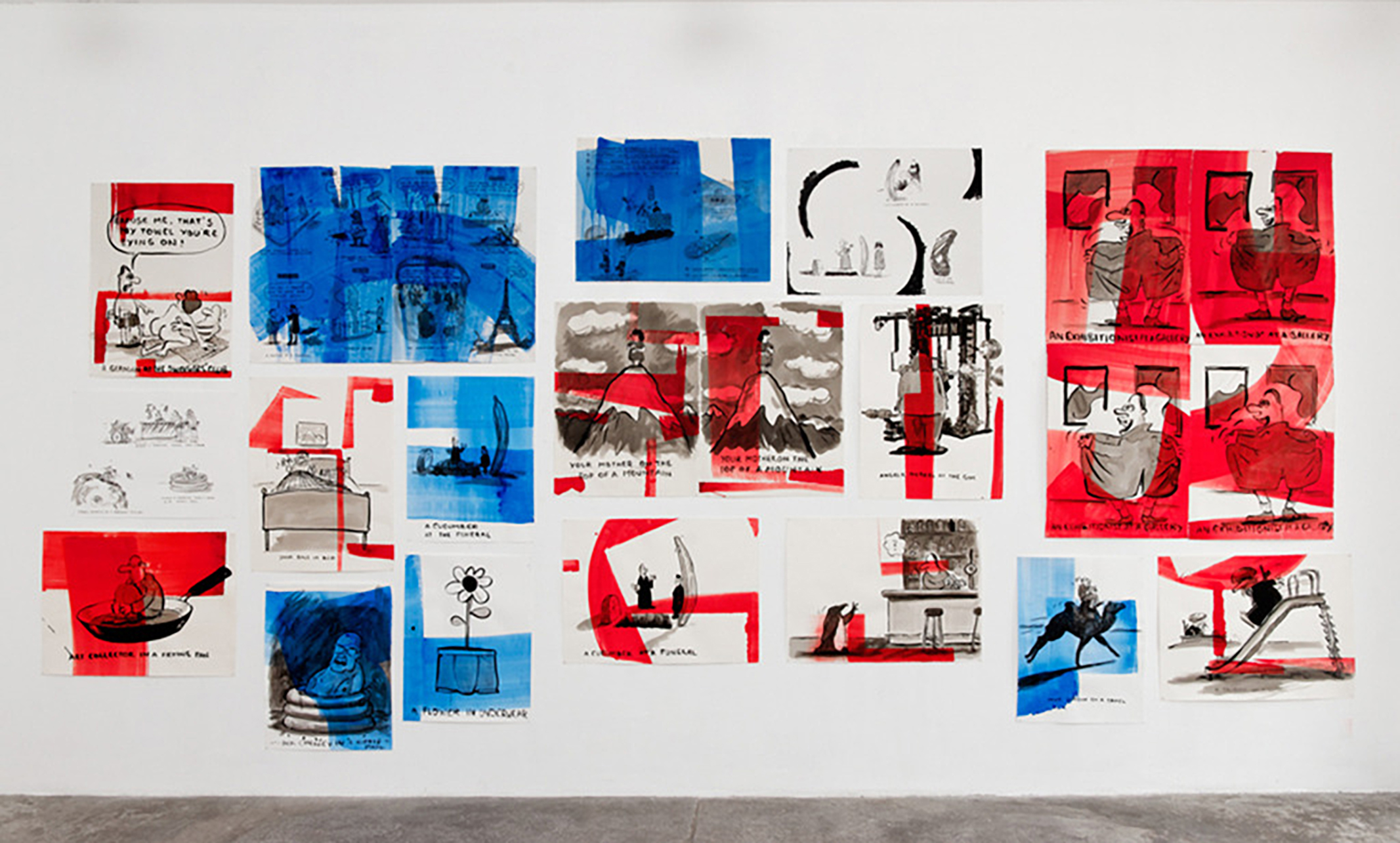

I made this group of drawings, combining a super-standardized cartoon language with—equally standardized—big, gestural brushstrokes in bright colours. They had a very graphic appearance. When we showed the series at the gallery it made sense to arrange them on the wall in a kind of layout. The reference material comes from print media, so it wasn’t surprising that they suggested the printed page. That’s also why I thought this specific series was going to work well in zingmagazine.

Generally, I love printed drawings. It’s something about the tension between the accidents of the hand and the precision of the technical reproduction. What can get lost in print, though, with this specific group of drawings, is the painterly aspect of the large swaths of color you mentioned. They do affect you in a different way when seen on the wall, simply because of their size and saturation. The brush strokes are pretty silly design elements, but they are also just a square meter of cadmium red, which you will, at least for a moment, perceive as a sizeable stained surface with all the accompanying painterly connotations. This slightly perverse experience may be harder to get from the printed drawings.

The overall project (“A junkie in the forest doing things the hard way”) was a way to think about inspiration, wit, creativity, those rarefied instants in an artist’s experience, as mechanical processes, as industry. I often felt that creativity was a type of mechanism. Certain elements, relationships and criteria are brought into play. It could be a given form, like the limerick or High Modernist painting. It could be a given content, material, or several of these elements. And then, in quick succession, random data is run through this arrangement. I think the difference between the formalized brainstorm at a creative agency and a poet waking up in the middle of the night, her heart aching with a deeply felt new image, may not be a categorical difference, even if the results differ a lot.

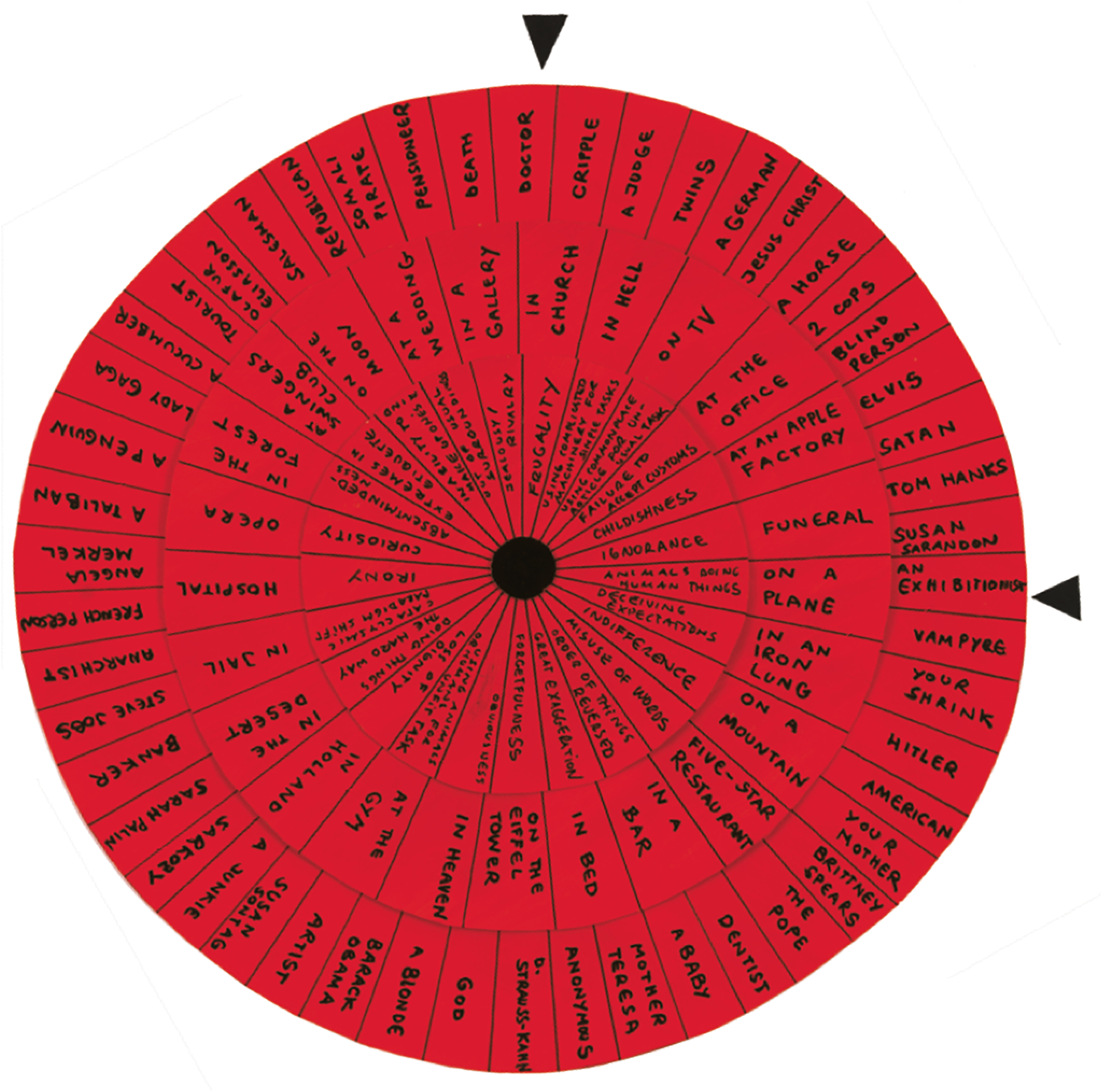

Glenn O’Brien wrote a great text, “The Joke of the New,” in the catalogue for Richard Prince’s show at the Whitney (in 1992). In it he mentions the cartoonist’s gag wheel, an aide for newspaper cartoonists invented in the 1930s. It’s made up of three concentric discs, which you can spin to line up randomly. The innermost wheel lists 25 types of comical situations. The center wheel lists 25 standard settings and the outer wheel 50 characters. This generates over 30.000 unique gag-premises. I loved that, and I made a whole set of wheels with different types of content for myself. I’ve used them in a cartooning workshop. They worked wonders for inexperienced cartoonists. For the ones that are already doing good work on their own, the difference was less dramatic. I think they had already internalized these mechanisms and could run them below the threshold of awareness. They were probably running them all the time. You know, we’ve all met some incurable punsters. There’s one in every extended family. It’s like Tourette’s. They scan every bit of conversation for a possible double meaning. For those people every good pun comes at the cost of many embarrassing moments. I guess the difference between the tedious uncle constantly issuing awkward remarks and the professional comedian may just be selectivity, having the restraint to not blurt out all the bad ones.

I have used the gag-wheel with performance artists and it worked even better. It made a shocking difference to some peoples’ work, maybe because some performance artists overrate authenticity. They can have a bit of a rigid notion of what they are truly about. And that gets redundant. So, the cartoon elements of these drawings are all entirely generated by a set of customized gag-wheels. And they are not censored. In that way, I am totally the embarrassing relative. There are some excellent jokes hidden in the series, there are some really lame ones and there are a lot of premises that never made it to the punch line.

Page from “A junkie in the forest doing things the hard way” by Olav Westphalen in zingmagazine issue 24

The swath of solid color across each image is another interesting element. Can you describe the purpose of the color?

The gestural over- and under-painting was meant as a parallel operation only in a formalist vernacular: a totally mechanical, repetitive way of producing these sweeping, expressive marks. I wanted them to be a caricature of abstraction. I think a lot of contemporary, neo-formalist work, knowingly or not, has that type of relationship to its historical models. I guess there was also an intended nod to an idea Mike Kelley once laid out—I think it was in “Notes on Caricature”—namely, that modernism was characterized by two opposing movements towards abstraction: a movement towards the idealized, heroic abstraction of modernist painting and a movement towards the abject, grotesque abstraction of caricature.

Installation view “A Junkie in the forest: doing things the hard way” at Galerie Georges-Philippe & Nathalie Vallois, Paris, 2012. Image courtesy of the gallery.

You are frequently associated with artists like Paul McCarthy and Mike Kelley. Which artists working today do you feel a strong connection with?

I like Mike Bouchet and his work a lot. I think Jessica Hutchins is great and in some weird way I think of her as a moral authority, even though I haven’t spoken to her in over a year. I love Alex Kwartler’s paintings. Peter Rostovsky is great and we have been friends and regular interlocutors for many years. I have learned a lot from that. I think Roe Rosen is amazing, as are Joanna Rytel and Mike Smith. I think Lisi Raskin is great. She just allowed me to borrow/develop on an idea of hers (“A rocket a day”). Lately, I have been doing music performances together with Lars Arrhenius, which has been so much fun. And of course cartoonist Marcus Weimer with whom I’ve published comics and cartoons for decades now (under the name Rattelschneck) is a real influence. But these are all people I have in some way worked with, or with whom I have at least a tenuous personal connection. I could name some household names and historical influences, like Cage and Kaprow. But also Fischli and Weiss, Rosemarie Trockel, Georg Herold (Herold much more than Polke or Kippenberger). Andy Kaufman, Nicole Eisenman, Allan Sekula (weirdly), Christopher Williams (I think he’s quite funny). But the personal connections are more important. I have realized about myself that I am basically a provincial artist without a province. I am always most intensely involved with the stuff that happens right around me, wherever that is. Even if, as was the case with Stockholm, there wasn’t a huge group of artists who shared my interests to begin with. A lot of the people I work with in Stockholm aren’t in the art world. They are comedians and film-makers etc. I convinced the philosopher Lars-Erik Hjärtstrom-Lappalainen to perform with me. You develop some type of loosely affiliated scene.

Your music project sounds interesting. Are you a musician? Can you talk more about this?

Ha! I am probably the least musically inclined person you will ever meet. But I like writing and I like using my voice on stage. So, my contribution to “Lars & Olav” is mostly the written and spoken word. I am pretty serious about the texts. Lars is musically very good and writes both music and texts. When we perform the sound is mostly pre-programmed, with us singing, speaking, shouting out texts live while we stand around awkwardly. It has all the quaint stiffness of a fluxus performance, but some of the beats are so well-written that people kind of start to dance against their will, or at least bob around.

With your history of moving around so much throughout Europe and the United States, what location would you say gave you the most inspiration, creative energy, meaningful involvement, etc.?

I guess that would still be Southern California. I had met and worked with an artist from California back in Germany, and that basically got me interested in contemporary art as opposed to comics and cartoons and perhaps writing. Because of that connection I went to San Diego for graduate school, which was probably the most formative period for me as an artist. People had an attitude towards art, very serious AND very open at the same time, which I still find really important.

You draw cartoons in English and German, and exhibit and perform your Art around the world. Deconstructing the barrier between artist and viewer/participant is an important element in your practice. How does having such a diverse global audience, which you engage with directly, influence your ideas and process?

I am not interested in getting rid of the artist/audience divide. I am OK with that division of labor as long as it is explicit and precisely articulated. I have done a lot of pieces in which the audience becomes actively engaged, makes a lot of the decisions and may even take the work away from me, but it was always a matter of ethics for me to make it very clear, that I was playing the role of the initiator, host, game-master etc.

When it comes to different audiences, I think one of the reasons I have been so attracted to entertainment as material and form, is that it transcends a lot of cultural specificity. But, still, sometimes you connect and sometimes you don’t. That’s where art is different from entertainment. It can be really interesting to be completely misinterpreted. Bad entertainment can be good art and vice versa.

There’s a video of your “Even Steven” performance at Art Brussels. And in that video you say how much you love art fairs and the market because they help artists evaluate their own work and provide the financial means to foster their ambitions. Have you always felt this way?

Well, there was irony involved. I don’t know any artist who doesn’t find art fairs at least somewhat problematic. That doesn’t mean they don’t serve an important function. You know the expression: An artist visiting an art fair is like a cow taking a tour of the slaughterhouse?

“Even Steven” starts out as a location-specific stand up comedy. So, as I was invited to perform the piece at Art Brussels at that time, I did a stand up routine about art fairs. It kind of meandered between acerbic criticism and a naïve embrace of the phenomenon. At some point in the performance I confessed that I was tired of being smart and critical all the time and that I really wanted to do something beautiful. I asked a professional dancer on stage and he danced a modern piece. It was about that contrast. Very touching. Only I couldn’t just let him dance but asked him to let me to dance together with him and then I became kind of competitive, even though I really am not a good dancer at all, which devolved into awkwardness. Still touching, but differently so.

What’s your opinion on the recent record-breaking auction sale of Picasso’s “Women of Algiers”?

Is it ok if I don’t have an opinion on that? I mean, it’s been quite some time now that the top end of the market has lost pretty much all connection with about 99% of living artists producing art, thinking about art, developing art, having amazing and important ideas and conversations. So, every new price record is a little bit like reading that the universe is made up of 500 more galaxies than we thought. You know, to me it seemed really, really big already. Who really cares? We read a lot about the market. But if you think about how much it is about social and monetary criteria and how little it actually deals with important questions, what a relatively small group of people we are talking about, you realize that it is quite provincial in its own right.

You are currently teaching at the Royal Institute of Art in Stockholm, correct? What kinds of courses do you teach?

Yes, I am a professor in fine arts with a focus on performative practices. The school is still largely in the tradition of the European Beaux Arts model. That means I don’t teach regular courses, but I work individually with students. I have a group of 15-20 students whom I follow pretty closely in crits, group crits, study trips, exhibition projects. I do can arrange arrange seminars and workshops, but that’s usually based on my own and the students’ interests. I am finishing up a one-and-a-half-year research project on Dysfunctional Comedy, basically a series of public events and experiments on joke strategies in contemporary art. Like I said, bad entertainment making good art. We’ll publish a book about this together with Baltic Art Center. That’s one advantage of the academy, that some projects which might have been funded through that system. What else? Together with the painter Sigrid Sandström I have been doing a recurring journey, where we take students to the Swedish Polar Research Station. They meet the scientists up there. And end up making work under pretty extreme conditions. We’ll go back there this coming winter. I think the best teaching is if it’s an extension of what you would be doing as an artist or an individual anyway.

Have you made any work at the research station, or another place with extreme conditions? What has the response been like from students participating on these journeys?

I haven’t produced any finished work at the research station. But on another trip to the arctic, to Kirkenes on the Barents Sea, I did make a piece that kind of flopped. I had had this image in my head, before the trip, of a completely white landscape, almost like a blank canvas. And I thought wouldn’t it be great to burn a stack of tires there, so you would get this column of smoke rising up vertically, a black line dissecting the plane. When I got there the landscape was white, but with so much variation in it that this cartoon-formalist idea of the arctic didn’t really apply. I got some tires anyway and found someone with a van to drive us out to some frozen lake. When we burned the tires it got really messy and even though the smoke was nice and sooty and black, it never really rose up as high as I imagined. So, the video we shot made it just look like a really far-fetched and lonely act of vandalism. Afterwards we had to clean up all that scorched and melted rubber. I am not sure it was worth it.

With your practice involving different media and collaborations, I am curious what your usual working environment is like. Do you have a dedicated studio space, or do you have a more variable/flexible kind of arrangement?

I have an office and next to it a modestly-sized studio. Both are very close to where I live. That’s important, that I can go there whenever and not spend time in transportation. I use the studio a lot when I actually produce something, but then there are times, sometimes weeks, when I don’t really go there and just read or write or sketch and do work on the computer. Which can also happen at home or wherever. I am not a post-studio artist, but an intermittent studio artist.

Is there any medium that you have yet to experiment with that you would like to try, or become more acquainted with?

I just now produced a digital animation for the Thessaloniki Biennial. It is based on a series of drawings I made. I really like that malleability, that the drawings already suggest their manifestation as virtual 3D-objects in a film. I would like to use 3D-printing to translate some of the objects from that film into physical sculpture. That’s a plan.

Gag-wheel in issue 24

Being a humorist, do you have a favorite joke?

Comedy is highly contextual. It doesn’t easily survive being transferred to another situation. That’s when you shrug and say: “I guess you had to be there.” Jokes on the other hand are supposed to be portable comedy. They are like the easel-painting of comedy. They carry their context with them, or rather, they rely on such commonplace contexts that they become, relatively, context-independent. I am terrible at remembering jokes. But I once worked for a German TV-show as a gag writer and the head writer asked me the same question, what’s your favorite joke? And then proceeded to tell me his. And that joke I remember till today.

What was the joke?

His favorite joke went like this: There’s a guy walking out about town and suddenly he sees a penguin in the middle of the city. He takes the penguin to the nearest police station and says: Look, I found this penguin walking around on its own, what should I do with it? And the policeman says, “You have to take it to the zoo.” The next day that same policeman is out on patrol and runs into the guy who’s walking down the street with the penguin. He walks goes up to him and says goes: “Hey, what’s going on? I told you to take that penguin to the zoo.” And the guy goes: “I did that was yesterday, now we’re going to the movies.”

What do you have coming up in the near future?

I am working on two book projects and we’re expanding the repertoire of “Lars & Olav.” We are preparing for a performance at a club in Athens in September and decided to produce a new piece, a love story between a woman from Kreuzberg and a tour guide on Crete, titled “Eurolove.” It’ll be danceable Greek-German techno.