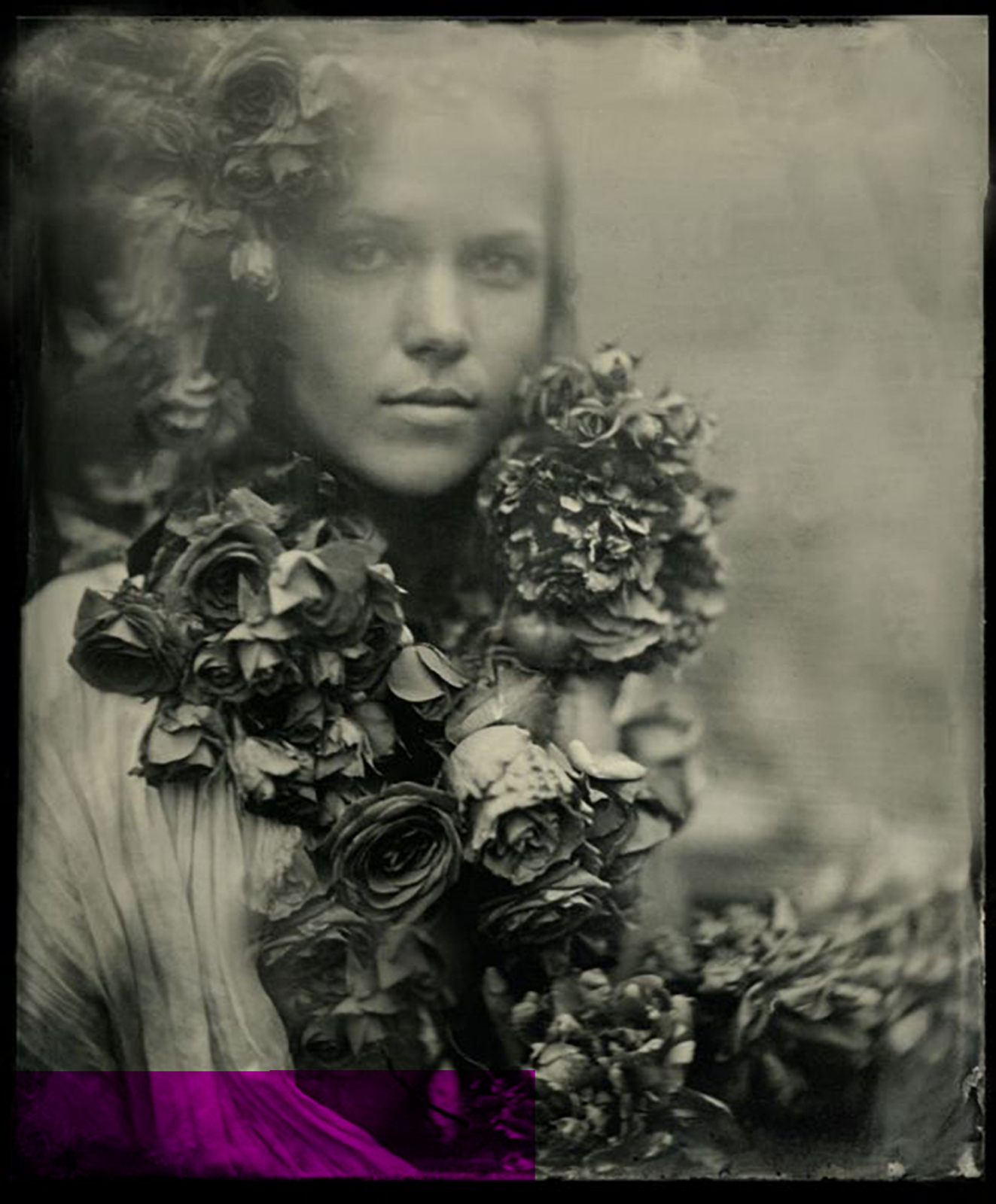

Portrait by Mark Sink, 2012.

With a portfolio that dates back to the late 1970s and an omnipresent energy, Mark Sink has made himself a steadfast pillar in the Rocky Mountain art community. He started his career in commercial photography in New York, canoodling with the likes of Andy Warhol and the rest of The Factory crew, and now lives and works as a fine art photographer and curator in his hometown of Denver, Colorado. Mark is fully dedicated to the medium, and prefers the traditional collodion process and aesthetic to the modern convenience of digital technology. His images, typically portraits and nudes ornamented by flowers, leaves, and water, are ethereal and haunting, and harken back to the work created by his great-grandfather James L. Breese who was an early twentieth-century photographer in New York. Right now Mark is working harder than ever to make this fair mountain city a known art destination on an international level, and he does so by showing endless support for artists and the venues that show their work. He was one of the original founding members of Denver’s Contemporary Art Museum, and curates dozens of gallery shows each year.

Mark’s most ambitious project to date, though, is the Month of Photography, a biennial citywide celebration of the photographic medium started in 2004, which is in full swing right now. This year he curated twelve exhibitions, all occurring during the months of March and April. Also during MoP is a weekly happening he organizes called The Big Picture, where artists submit their work to be shown in public as wheat paste posters. Of course he was generous enough to spend some time exchanging emails with me as he dashed around to meet deadlines and attend openings during what is undoubtedly his busiest time of year.

Interview by Hayley Richardson

In 2013, during the last Month of Photography, you did an interview with Gary Reed where you expressed that you were thrilled with how much the event has grown but cautious to not let it get so big that it becomes a struggle to manage. You said, “I like it the way it is right now it’s big enough!” In reference to that statement, how do you feel about the way things have taken shape for MoP in 2015?

I like the size it is now. We are at max capacity . . . I do MoP myself, my wife Kristen does the posters and fliers. We don’t have major funders. I like it moneyless. It has great potential and could be a cash cow of funding . . . but money ruins everything . . . it would ruin my MoP.

The show you curated at Redline, Playing with Beauty, is the signature exhibition of MoP and you’ve said it took two years to put together. Working with a broad theme, you must have come across an astonishing array of work. Did you encounter anything that challenged your perspective of beauty? What kinds of trends did you pick up on that might be surprising to others seeing this show, and what kind of work didn’t make the cut?

The title was first “On Beauty.” I changed it to “Playing with Beauty”. . . partly because I really opened Pandora’s box with the subject of beauty. My mission was to present my rather serendipitous encounters with the different interpretations of beauty with the human form and the western landscape.

Not making the cut . . . I was struggling with social documentarians and making them fit . . . I had a few in line like Kirk Crippen’s (love his work) and work from Africa . . . sometimes it was purely budget and or dealing with big Blue Chip Galleries that really look down on loaning work to little ole Denver. Borrowing work from one big east coast dealer was harder then assembling the whole show.

The Big Picture is another stand out event for MoP in Denver, and has spread all across the globe. How do you go about selecting which pieces become part of the The Big Picture? Also, why is The Big Picture a black and white project?

We have a standard submission link . . . the submission fee pays for the printing. I pick the work . . . I am the easiest judge in the world . . . if I don’t like the work submitted I often go to the artists website to pick something . . . often I find great work they didn’t think to submit . . . they go from the barely making it in to a top image . . . I also like picking from the website cause a I have more visual and curatorial control. People send the strangest things then their blogger site has amazing things.

It’s black and white because of the Kinkos plotter machine that makes the prints . . . it was made famous by Sheppard Feiry, JR, and others. Cheap fast easy and the thin paper absorbs the paste well.

The history of photography is quite fascinating because it has a rich variety of processes and styles. Now, with so many cross-disciplinary approaches developing in the art world, the qualities that define a photograph are continuously blurred. Galleries hosting MoP exhibitions are showing work that is sculptural, mixed media, etc. and placing it under the photography umbrella. Can you articulate what you see happening here? Is there a new movement taking shape that has no immediate connection to the photography process but somehow relies on it on some conceptual level?

Anything goes with art photography . . . Lots of searching is happening now.

I like the direction work is going that is true to the medium, not faking another medium.

Digital has remarkable new ways of seeing very low light with highly sensitive chips . . . and projectors are strong and can shoot on mountains and buildings, laser etching..great things are happening . . . why try and look like an old Silver Print or Platinum print . . . I hate that fakey instagram filter thing . . . that has swept the app world. Just awful, it’s a reflection of our fake-ness in society.

I see a movement with the gushy romantics in still life and portraits ..the master painters of light . . . the Vemeer light. People like Hendrik Kerstens, Bill Gekas, Paulette Tavormina.

A giant movement has taken off world wide with reverse technology. Pinhole, alternative processes, and conceptual of shadow and mirror. The early lost art crew is a huge quickly growing community I am close to. I personally am going reverse . . . I am at the 1850s with collodion tintypes and heading further back to camera-less and camera obscura.

Yes, your work has a strong connection to the past, both in the processes you utilize and with your aesthetic, which feels reminiscent of a ghostly, bygone era. You often cite your great-grandfather, photographer James L. Breese, as an influence and you feature his work on your website. You’ve done a lot of research about him. What has that process has been like, putting together the pieces of your family history, and how has it directed the course of your career/practice?

It has been slowly trickling in for several decades. Many times it’s another researcher looking for information on another character in his circle that will fire me up to put more pieces of the Breese puzzle together. All and all it’s very exciting to bring his story into the light. It has led me into researching that period in NYC in depth. History passed him right by . . . then I will get a book like ( Camera Notes by Christian A. Petterson ) the history of Camera Notes and the Camera Club of NY and there on the first page, “The primary inspiration of the Camera Club of NY was James L. Breese.” I find it interesting how much history passes over so many . . . including women.

I use his camera and lenses for some of my work so yes it has a pretty direct play in my work. And I love simple portraits of women. That is 90% of his work as well.

Throughout your career you have maintained a strong connection to the young, emerging artists of Denver and have undoubtedly become a great resource and mentor to some of these people. As an artist who honed his craft in the Mile High City in the 1970s and ’80s, how would you characterize this generation of local artists compared to those of previous decades?

It’s a new world . . . far more instantly connected and yet the community is somewhat a bit disconnected at the same time. Great unique ideas and talent always emerges and flies off on its own wings without much help. I enjoy watching this happen.

What I am most sad about is the new generation of young artists and how they are burdened by terrible debt from school. Crazy crazy amounts. Fanny Mae in co-hoots with the franchised for profit colleges and universities saddled on them . . . debts of 100k or more from a small local state school? Please. I have become very down on the higher education system for artists . . . it’s growing anger and sadness from many directions. I know many amazing educators but the system is driving a direction of under paid teaching staff, that then draws in really low level frustrated and angry educators, generally art world drop outs. I have personally visited many art classes in our regional colleges and left appalled and depressed. It’s a bad scene that nobody seems to notice or care about.

I agree. The higher education system is like a train running off the tracks when it comes to keeping costs manageable for students. I’ve reviewed artist submissions for galleries in the past, and directors often want to know what schools they graduated from before even looking at their work, so it can be very challenging for hardworking artists who can’t afford a degree to even get noticed. Do you have any advice for young artists struggling with this conundrum? What are some viable alternatives for an artist without a degree to be taken seriously?

I don’t have a degree so I am an example that it is possible to make it in the world without degrees. I wish I had an easy answer. If I had a magic wand I would trim a few nukes and put the billions into supporting art schools and students. History always looks back at the greatness of a culture by the art it produces.

Outside of the visual arts, what inspires you or has an impact on your work?

Walking my dog. Community gardens, getting to know your community through gardening, teaching kids . . . walking in nature.

You are a man who wears many hats: artist, curator, educator, community organizer…When you meet someone for the first time, and they ask “What do you do?” how do you typically respond?

Artist in general . . . During MoP curator . . . Asking a new muse to sit for me . . . a fine art photographer.