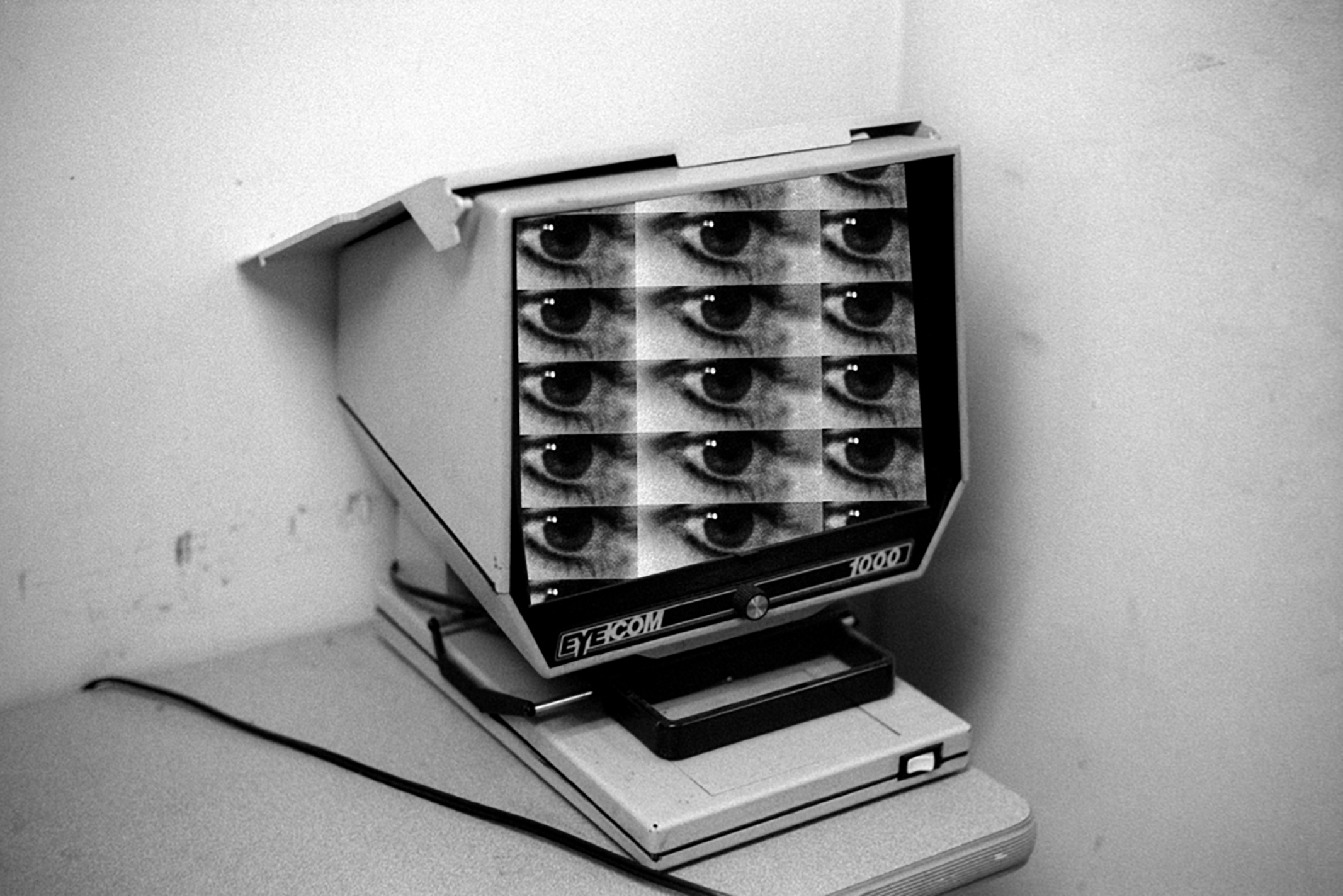

Maria Antelman, Eyecom, 2016, courtesy of Melanie Flood Projects

Maria Antelman works in photography, video, and sculpture, often through the lens of technology. Her latest exhibition, “My Touch, Your Command, Your Touch, My Command” opened at Melanie Flood Projects in Portland, Oregon on January 27th and is on view through February 25th. The work, a series of collages and a video, investigates human dependencies on informational tools and how these tools in turn shape their users. This exhibition is the fifth installment of an ongoing series at Melanie Flood Projects called Thinking Through Photography, which includes a comprehensive survey of contemporary photographic practices through programming that highlights experimental and diverse approaches to image-making.

Interview by Brandon Johnson

Let’s start with the title of the show: “My Touch, Your Command, Your Touch, My Command.” There’s a clear implication of control—losing control, but also being in control. The word touch implies something sensual, almost sexual. There’s a power dynamic that flows between two sources. Am I on the right track here?

In an uncanny manner, “touch”—sensual, sexual, personal, etc—turned into a technical gesture: I-touch. We touch screens all day. There are cuddling parties where one can experience the warmth of the human touch. Perhaps a new invention can be warm, soft screens at 98.6 °F, the temperature of the body. The collages in the exhibition show hands touching microfilms, the predecessors of big data. There was a time when one could physically touch information. In digital haptics every touch is a decision which releases a code which itself becomes a command. I am thinking of the hand as a tool. The thumb and the grip were related to the industrial revolution in handling machines. The index finger is the protagonist in this revolution. In the movie E.T., the extraterrestrial has an elongated index finger. The point of the index finger lightens up when E.T. feels a connection. The title of the show refers to emotional relations of interdependence with information and network systems.

Why use the dated technological form of microfilms in your collages? Is this related to being physically closer to information?

I was trained as an historian, to read the present and to think about the future through the lens of the past. Mechanical apparatuses are connected to our lineal thinking—one could make sense of how a machine functions. Digital devices surpass logical thinking; they are black boxes—one cannot understand how they work. I still use analogue film cameras because I need the slow processing time in a medium that is constantly advancing technologically. Microfilm technology is based on photographic memory, light and magnifying optics. In this body of work, these apparatuses are used literally and metaphorically to bring together the analogue past with the digital present.

There’s an element of Orwellian dystopianism to these works—like a scene from a David Lynch film where someone is watching themselves through a CCTV or is trapped within a monitor. Is there something inherently negative about our experiences with digital technology? And conversely, is there anything that redeems this?

You mean Videodrome by David Cronenberg which is indeed very tech noir. Communicating translates as the act of being social but in a digital format it has this transformative power, one that possesses people. There are so many platforms and choices: reviews, comments, likes, dislikes, loves, hates, faces and cute sounds. There is no silent time, time has turned into information, and information is data, and data is the new economy. I love my digital experience, it is super sexy and fun, and feels fresh, and we are all connected, and its participatory, and sharing moments can feel so good: it’s a validation. Perhaps there was a dormant part in my brain waiting to be filled with all this information and now this part is hungry: it needs to be constantly logged in, updated, saved, downloaded, etc. We are becoming automated: codes predict and cover all our needs and desires, and we never get lost, don’t close our eyes, rarely let go. It is a very interesting self-discovery. I like it (thumbs up emoji, happy face emoji).

I had Lynch’s Inland Empire in mind, but Videodrome works even better. There are some episodes of Black Mirror that also relate closely. Interesting that you speak of a dormant part of the brain being hungry and developing an appetite for information. I’ve always liked to think about how technology and communication fit within the grand scheme of evolution. How human language, tools, and abstract thinking allowed us to dominate the other species on the planet. It seems that technology has developed at a faster rate than our bodies (and brains) can adapt. The sheer amount of information is impossible to fully process and retain, in part due to the lack of idle time where reflection typically takes place—when we close our eyes and let go. Are reflection and imagination the antidotes to technology’s distraction? Or is this something that technology merely deprives us of? Are there aspects of technology that we need to resist?

I think the antidote to technology’s distraction is boredom. Sheer, old-fashioned, torturing boredom. Maybe we need to remember what it feels like to be bored. Then new habits may kick in. The problem is that the overload of information is getting boring as well. But while it’s constant input becomes repetitive, social media responses still release dopamine in our brain every time we get a FB like or even better a FB love. Now information needs to evolve, so our brains, hungry and addicted to their dopamine doses, will continue to stay engaged. Otherwise, we may turn into ADD zombies looking for exciting content to suck into. Nerve is a great teenager thriller. The story is about an online “truth or dare” game with players and watchers. The code of the game knows everything about the players from their social media and consumer profiles and uses this knowledge to challenge them in extreme, personally tailored situations. The more dares, the more likes and the more money gets transferred instantly in your bank account. Digital natives live in a different world. Most young entrepreneurialism is about some digital service: an app that replaces some gesture, some decision, some desire. Perhaps, it is all about mediating and facilitating experiences. Same as wellbeing, another new industry or the economy of wellbeing. I was reading the other day about this hi-tech, luxury meditation center somewhere in the Flatiron. A short meditation session leading to a nap (all in 20min), costs $18. It takes place inside a perfectly lighted dome room, with perfect sounds, blankets and pillows. It is a place where you don’t have to put any effort in meditating, instead you walk into a meditative environment equipped with the right props and boom, you think you are meditating. It is problematic. I think digital culture is picking up so easily because people understand technical skills better than experiences.

Getting back to the work itself for a minute. The Spacesaver works are collages, yet a viewer wouldn’t necessarily know it (especially when viewed on a screen)—they’re very seamless. Can you talk about your process in making this series? And since the show is part of an ongoing artist series at Melanie Flood Projects called Thinking Through Photography how the work engages with photography as medium?

When I got interested in microfilms, I visited a lab where they convert bulks of paper information into microfilms, from architectural drawings to checks and invoices. I ran some tests shooting with their duplicator cameras, with my hands in the shot handling paper. Then, I took those images, in microfilm format, and looked at them through the reader apparatus. It was very confusing and disorienting: the real and its representation were slipping into each other. I tried to capture this effect in my collages: a circle of motion from inside out and in reverse. I was thinking of screens opening to more screens, like a maze where you find yourself in every screen. Media is very narcissistic. Then, I started looking at technical, user manual and marketing images of apparatuses from the 60s. A female model poses with the device, touching it in a very soft machine-erotica style. The title of Melanie’s series Thinking Through Photography is very appropriate: images are the new communication form. Alexander, my son the other day explained one of his thoughts: numbers are infinite and combinations of language are infinite, so one day numbers will replace words. I will ask him whether images will one day replace numbers. Machines already speak images.