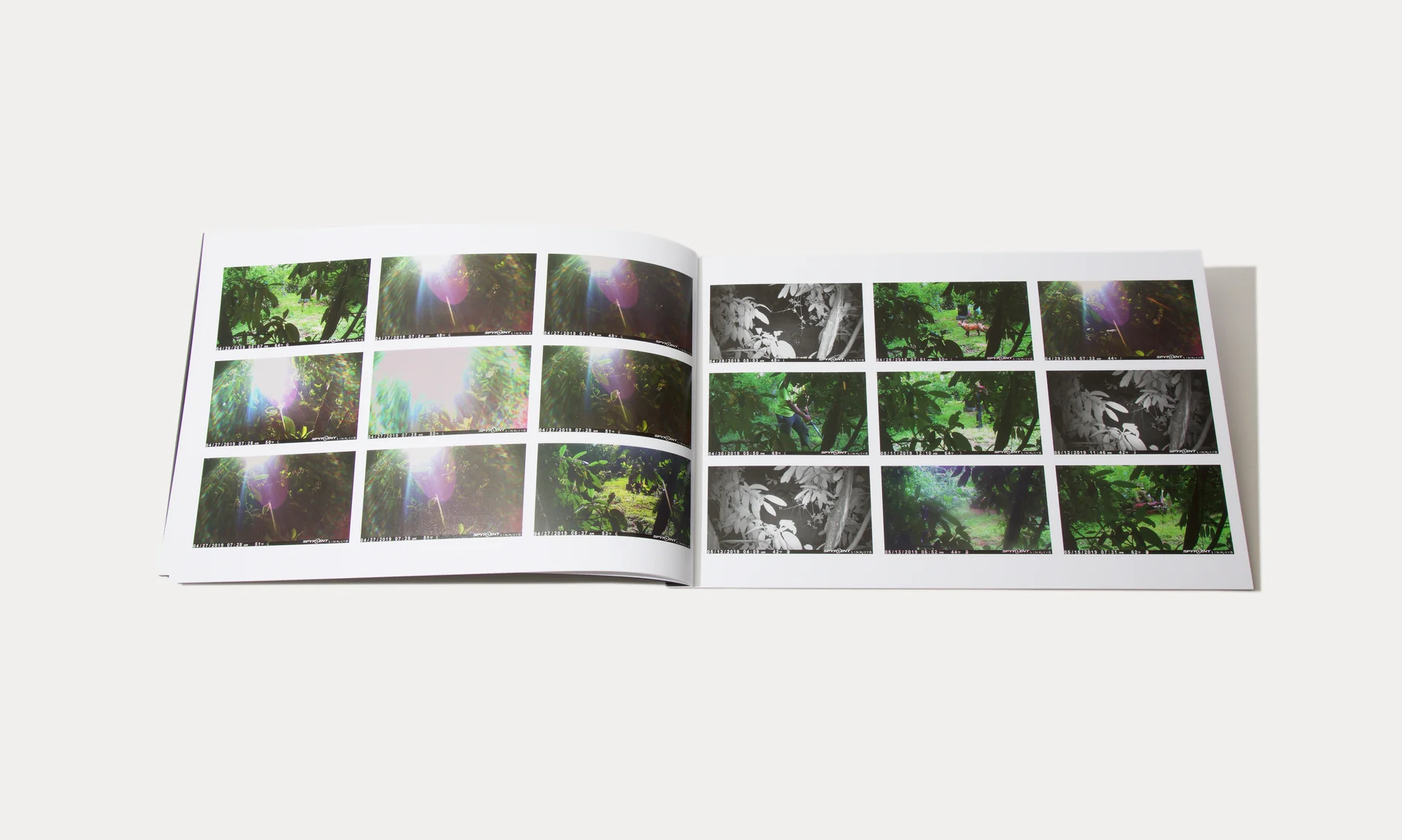

spread from MOURNING

Lisa Kereszi is photographer, mother, and educator living and working in New Haven where she serves as Assistant Director of Graduate Studies in Photography at Yale School of Art. Her work has been exhibited at numerous institutions, including Whitney Museum of American Art, the New Museum, the Brooklyn Museum of Art, and she is represented by Yancey Richardson Gallery in New York City. She has had numerous projects in the pages of zingmagazine; “Drinking” (zing 9), “Night Light” (zing 16), “The Priory” (by Benjamin Donaldson, curated by Lisa Kereszi, zing 20), “Peepshow Creepshow” (zing 22), and “The More I Know About Women” (zing 24), and her work is also part of the Dikeou Collection. Here we discuss Lisa’s work in relation to printed publications—the recently published photo-book IN (Roman Nvmerals) and the forthcoming MOURNING (Minor Matters 2024) that will be launched at Printed Matter Chelsea on March 21 from 6-8pm and April 25-28 at The AIDPAD Photography Show.

Interview by Brandon Johnson

Your work has been the subject of numerous books and magazines over the years. What does the role of printed publications mean to you as a photographer, and in your experience are there any specific challenges or considerations to translate the work to these formats?

I think photography as a medium really lends itself to reproduction, whether it’s on the page, screen, wall, billboard, photo album, in someone’s pocket or wallet—after all it is definitely firmly rooted in Walter Benjamin’s “art in the age of mechanical reproduction.“ A print on the wall might need to be large and can easily be seen at a distance, and maybe even needs to be seen at a distance. But when a photograph is in a book, it is held in the hands, or at least placed on a table, but either way, it’s a very intimate experience. It is often a private interaction, too, not an encounter in the public space of a museum or gallery. Photography first gets introduced to us all in books, magazines and family photos (not photobooks, but non-fiction, informational books in childhood.) (Today, I guess that’s happening increasingly more often than not on screens of varying sizes.) Other than billboards and posters and ads, most people outside the art world probably aren’t looking at too many framed photos on museum walls, so having my pictures viewed up close and personal in book form, smaller scale, feels incredibly natural. I actually pre-visualized IN being smaller, like 5×7”, for some reason. And MOURNING is big, as far as books go, because the publisher wanted the book to echo the handmade grids I assembled out of 4×6’s, and she wanted to put out a consciously large book by a woman as a statement. Women never unapologetically say, “I know that thing doesn’t fit on your shelf: deal with it.”

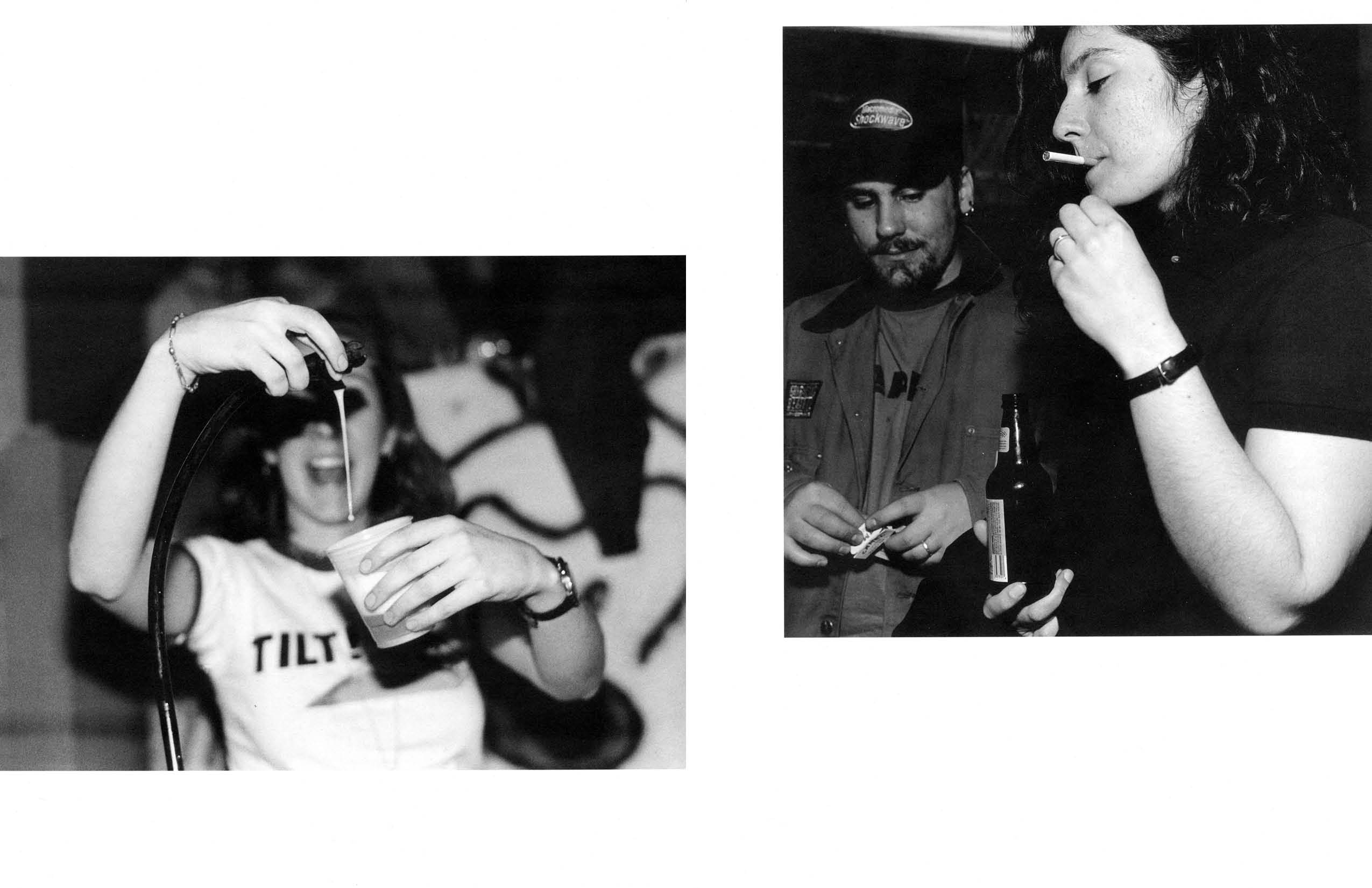

spread from “The More I Know About Women” zing 24

More recently, the subject of your work has revolved around family. Two previous books, Joe’s Junk Yard (Damiani 2012) and The More I Learn About Women (J&L Books 2014) along with a project in zing 24 “The More I Know About Women” engage in the sphere of your father’s life. And now a new book MOURNING that addresses his death. Another recent publication IN is a collaborative photobook with photographs made by “two parents and one child” (yourself, Benjamin Donaldson, and Ottilie Leete). What has led to the shift of focus to family at this part in your career?

Well, I guess it’s actually always been there. I conceived of the junkyard book before 1998 and showed the work that Fall in my very first critique in grad school, saying as much about my plan for it to be a book. I put it on the back burner but made a push in earnest to finish most of the pictures between 2001-2003, during my family’s last few years in the junk business. The book sat on various publisher’s shelves, on and off, for years, finally being published in 2012. It was a long-term investment! The More I Learn About Women artist book came directly out of the research in the family archive that I did for the historical photos I used in Joe’s Junk Yard, after my father handed me a huge stack of albums that contained his own photos that were adjacent to the business—his pictures of cars, motorcycles and women. In 2013 I got pregnant and knew instinctively that I wasn’t going to be the creatively productive person I’d grown to be, so I created that book, which came out the same year my daughter was born, 2014. I was right because it would be a decade until another book came out. But in putting two books out, pretty much at the same time, I guess I made up for the “lost” time. The time wasn’t lost, just focused into something, or someone, else, and also spent becoming someone else—a parent. In fact, the unpublished work I made to help overcome post-partum depression, was also, in a way, about family, or at least reinventing myself as a photographer with a family of my own. It is called “Walking With Ottilie,” and is all work made on walks with my baby, then toddler. (The work sort of ended when she became mobile, and unable to keep in one place in a carrier or stroller!)

spread from “Drinking” zing 9

But the work of mine that went more widely out into the world looked like it was about things outside of myself and my experience growing up in the family that I was in. And it was—but it also wasn’t. The pictures of bars, nightclubs, strip clubs, cheap motels and disco balls is all about escapism. In fact, the work that is in the Dikeou Collection was made as a response to family baggage. That black-and-white series, “Drinking,” was from my college senior thesis, and focused on drinking and drug use. It was my way to try to get into the mind of an addict like my dad and any number of boyfriends. I was trying to understand it. Those pictures of people partying led directly into the work I started at Yale, which was later in the 2008 and 2009 books, Fantasies and Fun and Games. It was all still really about a kid trying to understand why people like her dad need to escape reality. It’s funny, but my mom solidly being there for us enabled my sister and I to thrive and to become artists, but my obsession creatively is not with her love and care and attention, but instead with the guy who was absent at the dinner table every night.

These two books now are less about all that oblique metaphor around escape, surface and fantasy, and more overtly about family—the one I grew out of, and which is getting smaller year by year, and the one I’m now in and am building with Ben and Ottilie. And the form, themes and way that these newer pictures were made all fit into my busy, working-parent lifestyle—pictures I outsourced to a trail cam, and pictures I made with an iPhone in and around my house with my nuclear family all within arm’s reach, them both co-authors.

Your father passed in 2018, and at the end of that year his black granite gravestone “keeled over backwards under mysterious circumstances” (to quote Marvin Heiferman’s introductory text to your forthcoming book MOURNING). How did this incident lead to the genesis of new photography (from what appears to be the trail cam mentioned above), and ultimately a publication?

Well, someone knocked over his gravestone not soon after it was mounted, sometime between November 2018 and New Year’s Day, 2019. It is possible that it was something (like a deer) coupled with uncured or bad mounting adhesive (yes, you wouldn’t believe it, but these days it seems a squiggle of epoxy assists gravity to keep a stone on the base.) But given the fact that I was locked in a pretty terrible battle with my aunt over my grandmother’s home and things (she had also died less than a year before), I had my suspicions. Of course, I couldn’t prove it, so I went to photography to try to get to the bottom of it—should it happen again. My sister is the one who was in town for the holidays and discovered it, so from a few hundred miles away, I enlisted her and her husband to pick up a trail camera at a sporting goods store and mount it, then my mom and step-dad to maintain it, stuff like the firmware update and changing the batteries.

My dad died in early February 2018, and the one thing I did have control over was to swiftly get a memorial up before the end of the year. (The marker has etched into it one of my portraits of him in his cherished 1956 pink Caddy—“like Elvis’s” he would say, although the King’s was a slightly different year and model, but I am splitting hairs.) So, I imagined that seeing his face looking back at them from the grave was a final straw for her or someone. Or maybe it was “just kids” and a teenage prank.

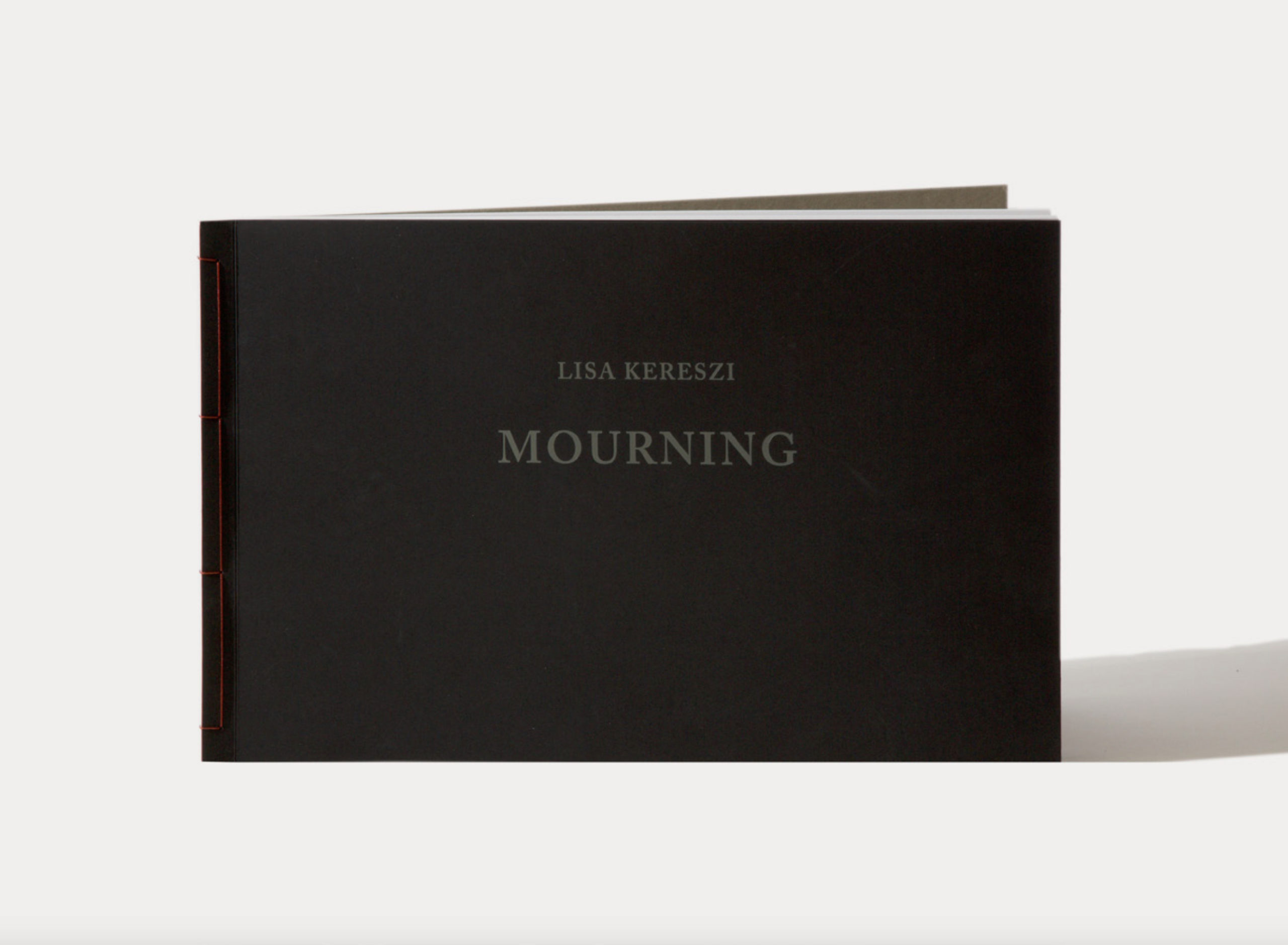

cover of MOURNING

I think the form of the book—those grid arrangements—was also my way of creating order in a sea of chaos. It’s bad enough to lose someone, let alone two people, and all the stuff that comes with dealing with the estates and grief and all of that. On top of that, to be locked out of my grandmother’s house (where he had a bedroom and a garage and backyard where he had kept full of his things), and to try to save any scrap I could grasp, became all-consuming for a year or so of my life. I was tracking down their belongings at pawn shops, consignment shops—even the free store, where my dad’s sister preferred giving things away rather than letting my own sister and I have any mementos. I also made a bunch of other grids of pictures of these material things I was searching for and feared lost, as well as other ordered collections of appropriated images.

All these grids are included in a bigger body of work about all of this family baggage and dealing with loss, and then about moving on from the family you came from and starting a new one. The work is entitled “Sunrise, Sunset.” As soon as I can come up for air, I will finish the series and the book dummy I have sitting on my desk here.

spread from MOURNING

MOURNING is a limited edition with handcrafted elements— board back with stab and thread binding. How did you and the publisher arrive at these material decisions for this content?

LK: During the pandemic, on Zoom, I showed this proto-dummy in loose print form to Michelle Dunn Marsh at Minor Matters Books, hoping she would want to publish it. (Michelle and I met in the Publications office at Bard College in the ‘90s, and she designed the junkyard book.) She zeroed in on the grids, and said she thought that that portion of the bigger project could be expanded on and made into its own thing—an artist book. So, she really was the one who quite literally pulled this “insert” type portfolio out of its bigger context, gave me the push and confidence to let it stand on its own, and then gave it life on the printed page. We toyed with an accordion-fold, thought briefly about a calendar-like format, but ultimately settled on something more like an album—a family album, whose color, shape, and form also echoes a grave marker or monument. So much of the aesthetic choices you are asking about were really collaborative and about me relying on her expertise and her own care and attention to the subject matter from her own experiences with grief.

To let her speak for herself, though, since this was so collaborative, Michelle says:

MDM: Lisa first showed me large pages where she’d taped photographs in grids. As we discussed the meaning of the work, and the forms the project could take, we tried a few different sizes, an accordion format, etc. But at some point, it felt like we’d overdone it, and lost the simplicity, beauty, and intention of what she’d originally created. So, we returned to the grids, and a similar scale to her artist’s book. Mourning has presence but is not unwieldy—you can hold this book in your lap and look at it, and that felt important. It is, after all, a twisted form of a family album.

I have a book from the early 1800s from Japan that is stab and thread binding, and I’ve always loved its visual vulnerability while knowing it is an enduring method of binding. That felt right for this body of work. Initially we wanted heavy board on the front and back, like two tombstones, but the front cover needed flexibility to function, so we went with a heavy paper, double-folded, and die-stamped the author, the title, and then the publisher’s name on the back board to create the physical indentation of letters. The book block, like the front cover, is scored, to relieve some of the pressure on the binding when a book of that scale and weight is completely open.

LK: As for the number of copies, 500 has been pretty standard for the number of each of my previous books—it’s an achievable sales goal for “Photoland.” Minor Matters has a crowd-sourcing model that requires presales that total the amount needed to go to press and print the book, and she usually sells 500 at $50 each. This book tested a higher price-point for it as an art object, since the grids I fashioned at home with 4×6’s and rubber cement are the exact same size as the book pages, so the book binds together replicas of the real thing I made. Selling 250 seemed like an attainable goal for this particular book: while many connect with the subject matter and the experimental use of a trail cam, I think there are others would also maybe not want to look at a bunch of low-resolution images that appear sort of artless and barely-composed, and which are about the death and sadness, to boot. But I hope the moments of surprise and light and life are uplifting, and express that life does go on.

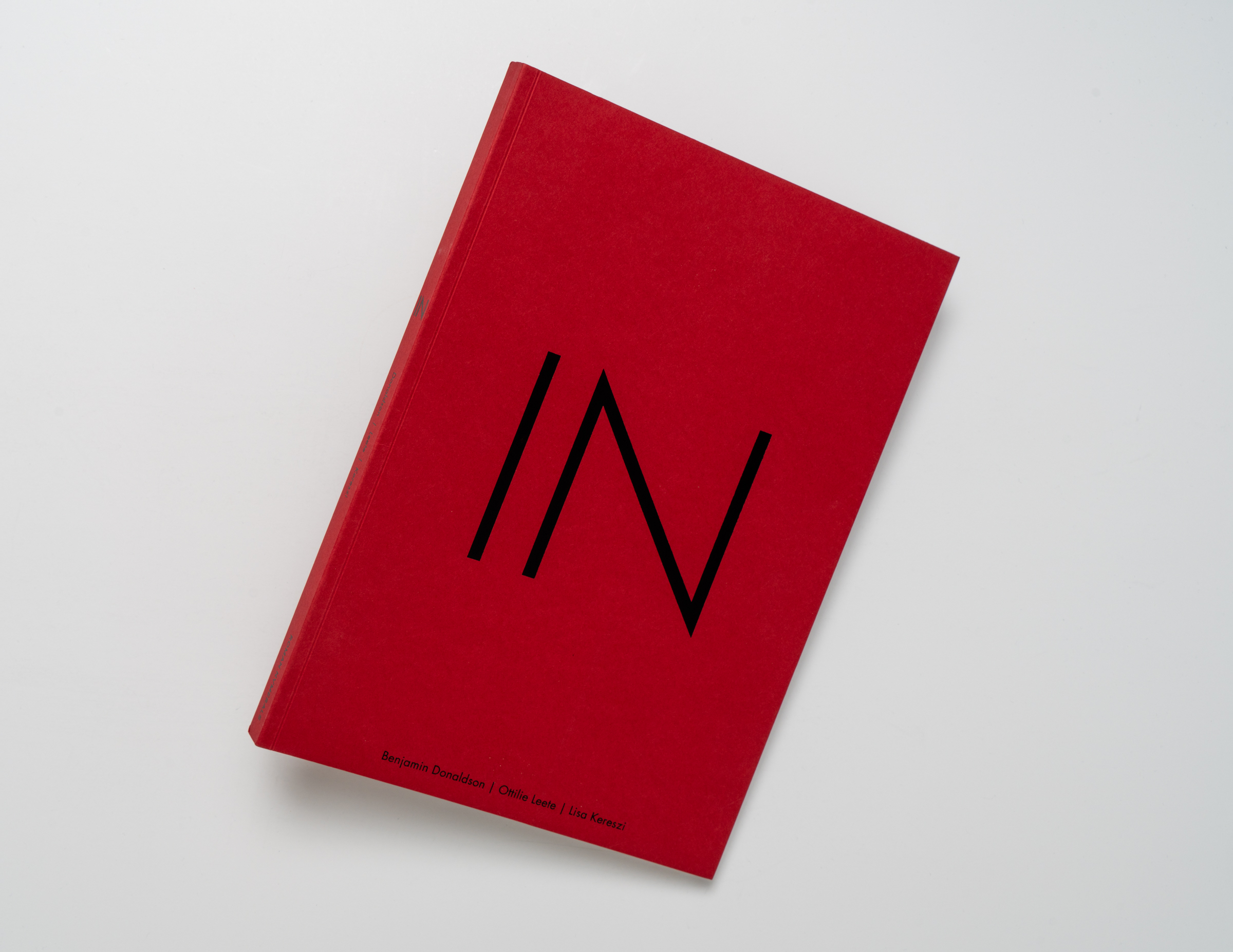

cover of IN

IN is an experimental artist book of photographs made with, as you said, your nuclear family beginning at the start of the pandemic lockdown in March 2020 through Spring of 2021—a situation that radically changed the lives of many into a new more intimate domestic reality with which many of us can relate. Was this body of work and publication just a natural result for two parent-artists and one child-artist living together during this time? And on an editorial level how did it feel to select and share these personal photographs with the public in the form of a book?

Benjamin [Donaldson] also answered:

BD: The project that the three of us undertook separately and together grew from us each needing to perform an act that reflected our reality and made a trace, when we had no idea what others’ realities looked like. It now seems to be a recording from a deep well.

Our family existed in this bubble together, well-aware that there were other bubbles percolating alongside us—everyone caught in their own experience. These pictures now live and belong together, having been made within the confines of the Pandemic days. There were times when each of us went into our own selves, even given our proximity, and our individual picture-making was part of that expression of self under the pressures that many of us felt. It seems to me that it was the natural expression of a family unit living through a very particular historical moment.

The photographs in the book form return these individual experiences to the roaring blur of our small entirety within the larger sweep of Pandemic time. After having such a spare amount that could be communicated with those outside of the three of us (except through a screen), this book stands as a physical memento that can be shared—something tangible that reflects love, terror, and a deeply personal historical record.

spread from IN

LK: I suppose we naturally all reacted to the situation and tried to cope by, among other things, taking pictures. I honestly just used my iPhone to take pictures of food and flowers, documenting the ups and downs of meal preparation and the annual cycle of rebirth growth and then death and decay that is part of the backyard and garden ecosystem. I had arranged all of these into a book that was as long as IN, actually, in which I guided the reader/viewer through the year chronologically with paired images of a meal and plants. I punctuated the sequence with beach-combing finds, since that was my solace and escape. Ben made pictures intermittently with a “real” camera and lighting of the staged or noticed magical and mysterious moments in the lives of a strange little trio in a big, weird house full of interesting stuff to look at and interact with, dressing up, acting out scenarios and making stuff.

Our daughter was 5 in March 2020, turned 6, then turned 7, and she “wrote” a handmade, construction paper book every day in virtual public school. Sometimes she taped photos in, but she usually drew the illustrations. During classes, and really, all day, she took to drawing and fashioning cut paper houses, with many rooms, and big families occupying them. You see a few of those drawings in the book. She also was encouraged to take pictures with a little pink (then a red) point-and-shoot, something she previously would do when we went to New York, rode the train, drove around to look at holiday light displays, or to document her toys or her face or anything she wanted to remember or save forever. The pictures she was moved to take on her own during this period were still of her toys and Christmas lights, but her out-the-window pictures took on new meaning, and screens became such a big part of her life that she took screenshots, of sorts, too. She also turned the camera on us as well as her food.

spread from IN

We arranged the pictures into three separate volumes, and that is what we approached Roman Nvmerals with: a 3-volume set to be slip-cased. One of the publishers, the photographer Michael Vahrenwald, instinctively knew that was not the answer. (Though Ottilie would vastly prefer that her contribution remain as her own, individual publication, entitled, “Ottilie’s Picture Book,” like the Shutterfly dummy I made.) He asked me for prints of everything, and on his own mixed them all together into something that retained the general chronology, but that was far more interesting. The book as he saw it was not really about individual authorship, but instead the linked rings of a trio who were trapped on this ship in an uncertain storm at sea. Both publishers had a stake in using these unusual, collaborative images in ways that had not exactly been done before. The form followed the content.

spread from IN

So, in both books here, I relied on and trusted in the collaboration with the publishers, who I count as friends as well as peers in the “business.” That mutual respect and willingness to let go a little bit and collaborate and see what happens is ultimately what allows both books to succeed as experiments, I think. I collaborated with my family in both books, with a motion sensing remote camera, with the writers and the publishers as our editors and guides, and ultimately with the Universe. That’s what photography is anyway, for me at least—a collaboration with what’s outside of us and being open to chance and change.

And so far, the feedback has been good. Sometimes when you put something so personal out in the world, you just kind of shove it out there and let go and then close your eyes tightly and wait. The writer of one of the book’s essays, Cindy House, early on let us know we were making something relatable and valuable when she so perfectly summed it up, “Here is a book of images that are both familiar and strange. Everything is recognizable and nothing is. I know the bubble, the isolation, but this is not exactly my bubble. This book makes me feel like we were all lost at sea in our own boats, none of us in sight of each other out there on the open water, just trusting that the other ships were sailing in the same ocean somewhere.”