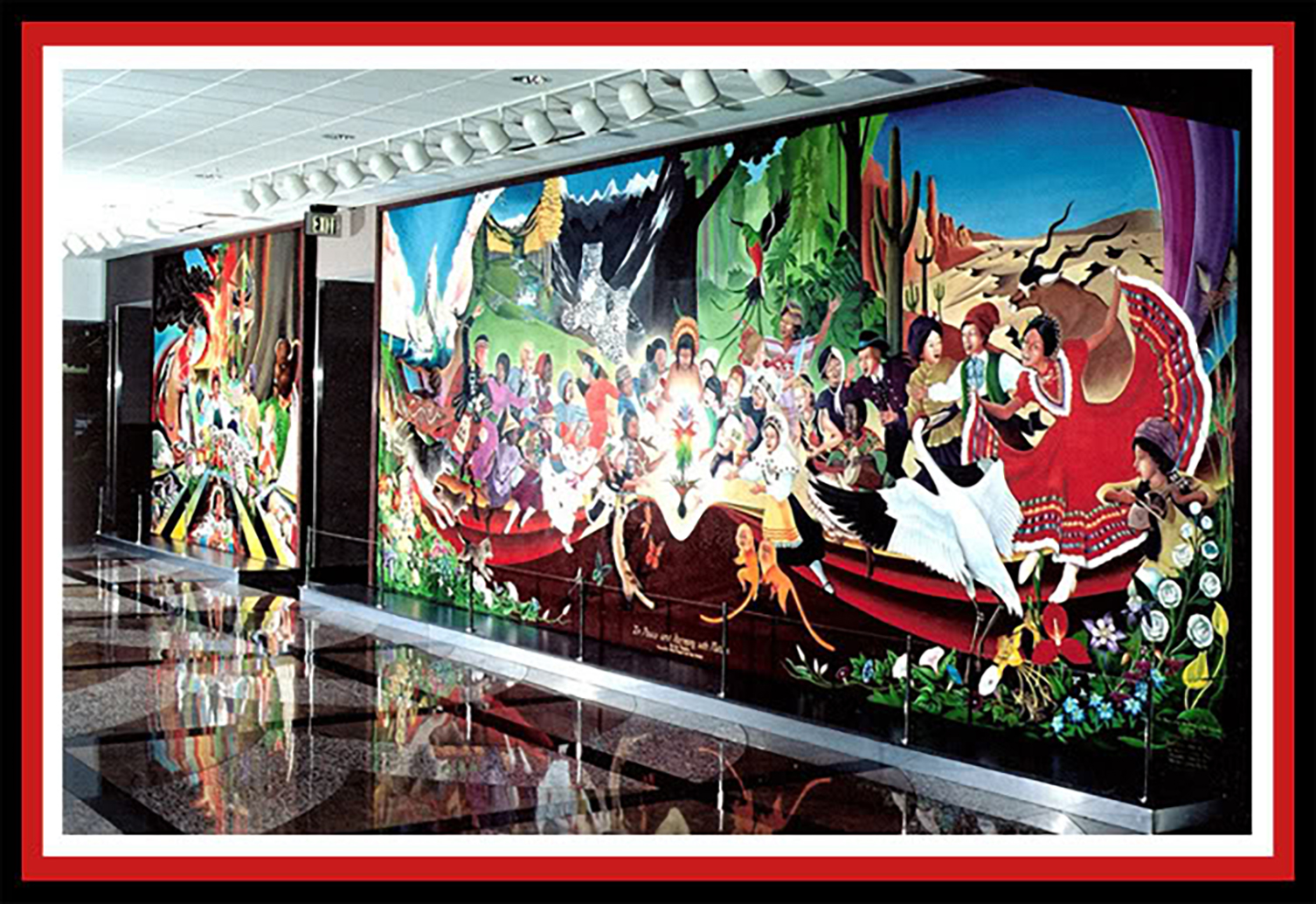

Leo Tanguma, the Chicano muralist perhaps best known by Colorado travelers and the subcultural blogosphere of paranoid doomsday theorists for his dramatic murals at Denver International Airport, creates his complicated pieces through an organic, multi-step process that weaves Mexican heritage, world history, spirituality, progressive social ideals, and personal anecdotes. He made his first mural on a chalkboard in fifth grade, depicting children lynching the town’s corrupt sheriff, for which he was severely punished, and this experience stoked a rebellious verve in his artistic practice that would be played out during the coming decades. Much like Los Tres Grandes—Diego Rivera, José Clemente Orozco, and David Alfaro Siqueiros—from whom Tanguma draws his artistic heritage, he has a keen interest in politics and cultural theory, of which his views swing decidedly left. His sprawling, complicated, large-scale public artworks do contain a number of secrets: portraits of real people lost to street violence, unsung heroes from the margins of history books, and the reexamined Chicano myth of a weeping woman, for example. “Children of the World Dream of Peace” and “In Peace and Harmony with Nature,” the murals that Tanguma created for Level 5 of the Jeppesen Terminal at DIA, were almost never to be: Tanguma barely made the proposal submission deadline. As of this year, he has completed dozens of murals at various public venues across six states, painting themes of childhood courage and idealism, environmentalism, multiculturalism, and Tanguma’s uncanny signature of socially-conscientious spirituality. His most recent work in progress is inspired by the Occupy movement, the pencil drafting of which, sits on a modest, clean desk in his home studio.

Interview by Rachel Cole Dalamangas

Can you walk me through some of the imagery of your murals? Who are the people in the background?

Many of them are real people. This is an anonymous community and an anonymous community can be anybody. In this here, there are the symbols of oppression that our [Chicano] community has overcome. Are you familiar with that figure?

points to a stylized figure with three faces on drafting work for his mural, “The Torch of Quetzalcoatl,” commissioned by the Denver Art Museum

No.

Well it means the fusion of the Spanish and the English when the Spanish came and brought women and began to rape and marry the indigenous women and introduced a new breed called, mestizo. And so that’s the essence of our identity.

And this figure, this is La Llorona, the weeping woman who destroyed her own children after having married a Spaniard, a conquistador. The Spaniard at one point decides to go back to Spain and to take the children with him. Well, that drives the woman mad because to them Spain was like Mars to us or someplace really distant and remote. The legend says that she drowned her children so that the husband wouldn’t take them to Spain, away from the New World. In my mural, I make La Llorona find her children because we get these stories from the Spanish historians and they had a very prejudicial view of the native peoples, that they were less than human, and we get a lot of our folklore from the Spanish males. In my mural she is shown reuniting with her children and it is a very happy occasion.

At the Denver Art Museum, a lot of kids come from the schools, the projects, from schools that have a lot of Mexican-American kids. When I tell the kids about her and say, “Do you know what La Llorona means?” they say, “Yes, we even know where she lives, there under the bridge.” She’s a really intense figure in our memory I guess. But then I tell them, “Don’t you see, somebody said that she killed her own children, but I don’t believe she did it.” Maybe she did, maybe she didn’t, but I don’t want to project that story anymore. So I tell the kids, “I have La Llorona find her children and she’ll stop crying and stop searching for them through eternity, which is what God condemned her to do.” Then I tell the kids, “They lived happily ever after. Don’t you want to live happy ever after.” And some of those kids had tears in their eyes.

Do your murals exist as wholes in your mind or do they develop as you start to draft them?

They develop. I search for ideas. I think it starts with something in my memory. For example, we were Baptists all my years growing up, even though the Baptists are really really conservative and there were ways that some of us weren’t in agreement with the general things. We’d hear from the pulpit, “Hispanic boys will not be found with those protesting,” you know, with those in the youth protest movements, and of course, some of us thought, that’s where we should be instead of sitting at the church.

points to pencil drafts for “Children of the World Dream of Peace.”

This is a lesson from the prophet Isaiah and Micah, that some day the nations of the world will stop war and so on and will beat their swords into ploughshares and their spears into pruning forks. That’s taken from how I was brought up. My parents were really religious when I was growing up, but innocent in their beliefs. I was the one who always questioned everything and I got worse as I got older. So you can see this comes from my religious ideas. As you can see, the people of the world are bringing their swords wrapped in their flags to be beaten into ploughshares.

Then here I have children sleeping amid the debris of war and this warmonger is killing the dove of peace, but the kids are dreaming of something better in the future and their little dream goes behind the general and continues behind this group of people, and the kids are dreaming that [peace] will happen someday. See how the little dream becomes something really beautiful, that someday the nations of the world will abandon war and come together.

What happened up on top here, when we were painting the mural at our studio at a shopping mall, some people who had their kids killed by gang violence came and said, “What are you going to paint up there?” I said, “Well, I have to look at the drawings.” They said, “Could you put my boy or my girl up there? She was killed.” And then they told us her name, Jennifer. This girl, Jennifer, was killed by a young man. She went to help her friend who was hiding with her baby from a man in a motel someplace, and they didn’t have anything to eat or diapers. So Jennifer took her some money and the boyfriend followed her. When Jennifer got to the motel room, the man followed her in and shot her right there dead and then dragged her friend and the child out. So her parents wanted her portrait put up there. They must have told other folks, because before I knew it other people came and said, “I know you, you painted [Jennifer] up there. Could you paint my son, Troy.” So now it’s got like ten kids here, all killed by gang violence in Denver. So the mural took on a new meaning that we hadn’t anticipated. Almost all these kids in here are real people. I put in my granddaughters and their little friends from elementary school. Like more than twenty-five kids from around the schools are in that mural.

The conspiracy theorists have interpreted it in the most naive way, I could say, like they think I advocate war and all these horrible stories.

Have the conspiracy theorists ever harassed you?

Just a couple of phone calls. They were not mean though. They’d say, “Are you the one who painted that?” And some came to my studio and wanted an explanation, which I gave it to them.

Even an explanation didn’t placate them?

Well, the airport never posted a complete explanation. They just put the title, the artist, the materials.

So how did you learn so much about history?

I just was interested in reading.

What happened I think was that something happened when I was growing up in Beeville, Texas, a little town fifty miles north of Corpus Christi. Like many little towns in Texas we had very racist sheriffs and police that liked to keep Mexicans in our place. In our town it was a sheriff named, Vail Eniss. One time the sheriff went to see about some minor thing between a Mexican husband and his wife about their children. The young man was not there, but the father was there. The sheriff arrived there with a semi-automatic rifle – now why if you’re only concerned about a minor incident? So he gets into an argument with the father and shoots him and as he shoots him, there’s other people that were in the yard that came around and he shoots them also. He killed three people in a few seconds. The man at the front was my mother’s uncle, Mr. Rodriguez. So in our family that was talked about. And in other families also. For example, my brother-in-law was put in jail and the sheriff personally beat him with a hose. I don’t know for how long, but severely. It was really really bad. He was just drunk, that’s why he was in jail. So we had a kind of a hate for the system because those things kept happening and the sheriff kept being exonerated over and over and over until he retired with honors.

So you see, we already had a disposition, some of us, that there was something wrong here. Why were treated like this.

When I was in the fifth grade, one day our teacher didn’t show up, so a lady from the office came and said we were going to have a substitute and later she would arrive and for us to stay at our seats and behave. And when the lady left everyone began to play and talk and stuff. Some kids went up to the blackboard. I was more reserved than most folks. We were a little odd. Some of us were Baptists in a community that was almost totally Catholic. So we were a little more reserved. I was sitting down for a long time and some kids were drawing already and after a little while I said, “Okay I’ll go draw too.” So I went up to the blackboard. I didn’t know what I was going to draw, but before I could draw, somebody said, “Pollo, draw me killing the sheriff.” Also all the kids began to say, “Draw me too! Draw me too!” So I started to draw the sheriff hanging or being stabbed. Then the substitute walked in. She was outraged at what she saw. Of course, when I saw her, I ran and sat down, but she had seen me already. She looked at the drawings and she said, “You, come here and erase this garbage.” I began to erase it and she got a ruler and began to hit me across the back. She was in a rage. And I began to cry. I guess I couldn’t see too well because I thought I was done erasing so I ran back to my seat and she said, “Come back here, you’re not done yet.” Because I hadn’t finished it completely. So I erased it completely. She hit me a few more times on the back. I don’t remember too much about what happened after that. Whether I went to sit back down or just stood there. For a while I stood there.

Many people have asked me when was your first mural, thinking I’m gonna say something like when I was in the boy scouts or something like that.

That I think started something in me.

Tell me about some of your artistic influences.

I met the professor in the art department, Dr. John Biggers, at the Southern University in Houston, Texas. He was a radical and he admired the Mexican muralists and he taught about them in a class I was in with him. Then I told him about the murals I was painting. And we became friends. So I was so influenced by Dr. Biggers. And he said go see the muralists in Mexico City.

What happened in my case was there were people, Los Mascarones, – masks – and they did a performance and so after the performance a lot of those kids [in Los Mascarones] stayed in my home. I had an enormous living room. After the performance they were at my house and the kids were sleeping already and I was having coffee with the director of the group and I asked the man, “Do you know anybody who could get me introduced to Siqueiros.” I was asking this guy – Mario was his name – and he said, “That’s his grandson sleeping right there.” I wanted to go wake that kid up. In the morning, I said, “Could you introduce me to your grandpa?” And he said, “Sure, just come on over.” So that’s how I met Siqueiros.

It was real funny. Siqueiros talked about some of the other guys, like, “Those guys can’t paint,” talking about Rivera. It was funny because Rivera is a Great. A great, great master. And then Siqueiros said, “Tamayo was okay, but one time we had a fight at the Palacio de Bellas Artes in Mexico City.” Siqueiros said that one time he and Tamayo got in a fight at the top of the stairs and rolled down the stairs.

Do you know much about the great muralists from Mexico?

A little bit . . .

Well Siqueiros was the most outspoken of them. Before the revolution began, like 1911, he was a student at the Academy of San Carlos in Mexico City. He and the other guys, he must have been 14, 15, and they were meeting already about political issues that were being discussed in Mexico before the revolution. And Siqueiros talked about this when I interviewed him. It was another awakening for me. Siqueros was so dynamic and a little reckless also. Do you remember Trotsky? Trotsky separated himself from Stalin and the rest, and Trotsky was a little more progressive I think. But Stalinists thought that he was dividing the worldwide communist movement and so they wanted him killed. Siquerios was a Stalinist in those days when he was young. When he was older he didn’t want to talk about it. He’d say, “We were young then.” He tried to assassinate Trotsky himself before Trotsky was finally assassinated. And that’s the way he was, kind of crazy and reckless and so on.

But to meet him when he was, I think, 72, it was quite an experience for a young person like myself. So I came back thinking, “Wow, I met a master, a real master.” Because there were many of us painting murals, but we didn’t know what we were saying or what we believed in or what our purpose was in painting the murals. I came back with a little more beliefs.

How many murals have you painted in Colorado?

I don’t know. But I’ve got some in schools, the high schools.

And some in prisons, too, right?

Did I do one in a prison? Yes, that’s right. In Greeley, there’s a youth facility. We did two murals there. When we were working in the prison the kids there were 10 years to 20 years of age. They didn’t call them inmates, they called them students. They were there for different offenses. 37 kids volunteered to paint murals with [my assistants and I]. We told them the way we were going to do the murals was each of them was going to sit down and draw from their own experience how they got in trouble, how they got their lives messed up at this early stage, and they were going to draw that and then they were going to draw another drawing about how they were going to improve their lives. So many kids didn’t like the idea so they quit coming in. We only had 15 kids. But some of them couldn’t see a way out. This one girl, her name was Alicia, she drew some big bottles like alcohol drinks and there was a little girl at the bottom lost in alcohol. And I said, “Okay, now what’s the other one, how are you going to get yourself out of this?” And she wouldn’t do it.

Everybody painted a portion of the mural, about two and a half feet wide by twenty inches high, and they would paint how they had gotten in trouble, the life they had, and how they were freeing themselves from that. And Alicia left hers just like that. She said, “Once an alcoholic, always an alcoholic.” So I could never make her go beyond that. Another kid named John, he drew himself in a big rat trap, and I said, “Well, what are you going to do when you’re on the other side?” And he said, “Once you get in drugs and messed up, that’s the way you’ll be forever.” And I said, “No.” And we were kind of preachy the three of us, my two assistants and I, we were trying to tell the kids there’s something better out there, like, “Paint yourself some other way.” And John did change his drawing. He’s got the kid trapped and then in the other one there’s a trap with the wire back and the kid’s standing next to it, because he’s gotten himself out of that situation. And that’s how it’s painted on the mural today. It was therapeutic, what I was doing with the kids.

I’ve told my students, “We have to have a higher purpose with our art here, not just to sell it so people can take it and just decorate their homes, but do something more positive.”

Can you expand on that? What is art’s role in cultural and political conversations?

Well, the Mexican muralists after the Mexican revolution proceeded to paint the people because many of them had been with the revolution and had seen the struggle of the people and they saw firsthand how art could return to the people a sense of their own dignity.

Just to give you an example of how the elites in Mexico saw their own people, Mexico celebrated its 100th anniversary in 1910 and to celebrate the 100th year they invited an enormous exhibit of art from Europe, from Spain especially. Now how did those guys see the Mexican people, the Mexican artists especially. Why couldn’t they have an exhibit of Mexican artists celebrating Mexican independence. So that could give you an idea of how the rulers saw their own people.

My activism was in painting murals and working with kids and so on, but in my case, I already had the experience of being back in Beeville with the sheriff, and drawing him on the blackboard. The young people see themselves in the murals.

And in my background I had never gotten away from my beliefs. Because my parents were so beautiful. Memories that you could never forget. Like before going to bed, my little brother and myself and my older sister, and everybody’s going to bed, my mother takes a little time to sit in her rocking chair to sing or just hum hymns, and I grew up seeing that. Or hearing my mother or my father at the dinner table saying, “Remember the poor.” A list of things that they repeated almost in every prayer. So that was the kind of innocent background that I had in my case.

Some other artists did it because the Mexican painters were revolutionary in the Marxist way. Being not very easy with words, I tried to read Marx, but it was just too complex and boring. On the other hand, the Bible was easy for me and to see it in my family and going to visit my brother in prison and seeing all those things, they were impacting me.

So as I began to read history, Mexican history and then the history of us here in the U.S., and I saw how I could contribute.

For example I painted a mural about black and white. It was four or five feet off the ground, 18 feet higher up, and I painted many bodies, brown bodies, because we had been made to feel inferior to the whites. I remember seeing also in the 7th grade for the first time the black kids, the Mexican kids, and the white kids were all together, and I remember the black kids, when they went to speak to the teacher, and the teacher spoke to them, they lowered their heads. We were pretty bad, us, the Mexican kids. But we didn’t do that I don’t believe. We didn’t look the teachers in the eyes very much, but we didn’t lower our heads I don’t think. And I thought that was out of some humiliation and as I studied more about blacks and other oppressed peoples, I could see that what I had was an instrument in my hands that I could use to return to the people a sense of their history and their beauty and their human dignity. And people responded to that. They like those kinds of explanations.

Tell me about what you’re working on now.

I’m thinking about this mural for the Occupy movement. I don’t have funding yet. I think it’s very important and very interesting, what the young people are trying to do with that.