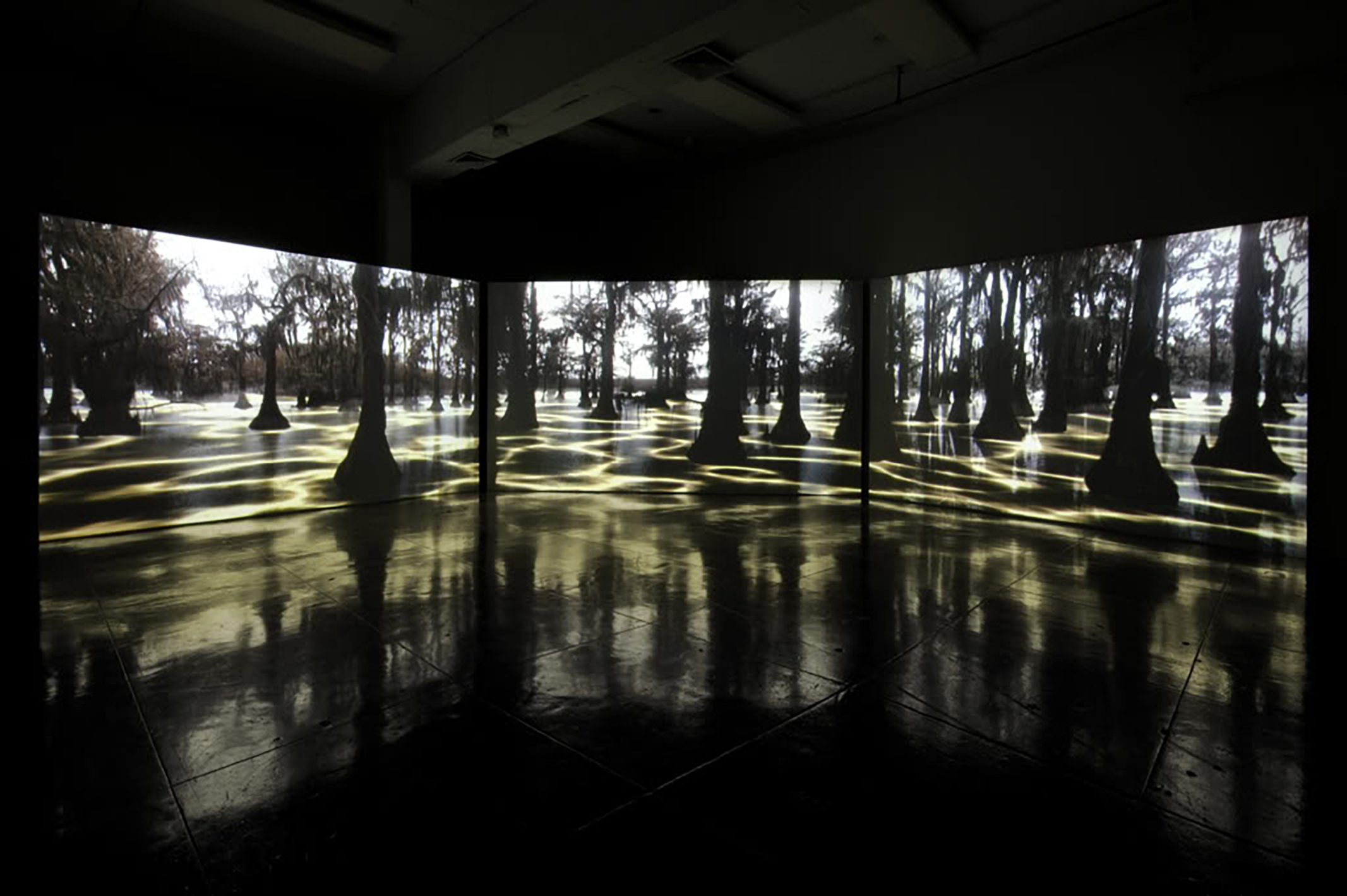

LEVIATHAN, 2011, three-channel high definition video, 20 minute loop.

Originally commissioned by Artpace, San Antonio

In the aftermath of a week with both a hurricane and an earthquake on the East Coast of US, and year in which, Japan has been devastated by an earthquake, a tsunami, and its Nuclear aftermath, and with a year of the most devastating oil spill in history, Kelly Richardson’s work has the relevancy and chilly methodology to wreak havoc on the otherwise still perceptions of her subject matter. She embraces a 19th century axiom—“The Apocalyptic Sublime”, with the precision that George Lucas first explored in his THX 1138 or the clever tautology of Ridley Scott’s Blade Runner. Her work captures fear, anxiety, resolution, beauty, mystery, omnipotence, awe, and desolation people feel in the presence of the unknown both in nature and in life. I had the pleasure of sharing a residency with Kelly Richardson at Artpace in San Antonio, curated by Heather Pesanti, and was initiated into the weird and luxurious sensation her video installations evoke. And now I have begun to look at the world through some different viewfinders, and like with all good art, wine, hallucinogens, or sex—after experiencing it—the world seems a little different, a little more fragile, and yet, a little more epic. What follows is our emailed Q&A, or “Come on Irene [sic]”.

Interview by Devon Dikeou

Terra Nullius, landscape work not touched by humans would seem to have a strange relationship to you and your work. You live in the UK—the ultimate non Terra Nullius landscape—it has been centuries being sullied, sculpted, terrorized, or tamed. And yet you try to find landscapes that might have any or all of these qualities in both hidden and obvious ways, and then you digitally create some effect—in effect a super Terra Nullius. Can you speak about this . . .

I’d say it’s increasingly true that the work focuses more and more on locations without signs of human interference. Occasionally, there are works which use manmade structures of some kind, but many of the ideas dictate using the Terra Nullius landscape. Most often, unplanned indicators of civilization inform the work in ways which don’t support what I’m after. If elements of sullied landscapes are present in anything I make, it’s deliberate; either it has been inserted digitally or selectively left in the shot to support the idea.

While majestic and beautiful, the work should also have an eerie, if not terrifying quality. If they function properly, the viewers feel consumed by the landscape, losing themselves in the work. If there are signs of a tamed landscape, the threat of the un-urbanised wild isn’t present which prevents fear of the potentially unknown.

Let’s talk about what Woody Allen calls, “Your early funny work”, and your early work is really funny, literally. Like the “Ferman Drive,” or “The Sequel,” much less the “Wagons Roll” . . . Humor, what are the advantages and disadvantages . . .

I used humor in the past as a way of inviting people into the work. From there I was hoping they would unpack it and end up feeling all sorts of other, often conflicting sensations. At some point though, I guess it was 2006, I decided that humor was far too specific. I’ve always tried to make ambiguous works where the viewer is unsure how to feel about it; it may be beautiful but at the same time unnerving (as above) and while humor is a great entry point, it ran of the risk of overshadowing what I was really after, the conflation of numerous ideas and interests which inspire a kind of contemporary sublime.

The Erudition, 2010, three-channel high definition video, 20 minute loop

This movement that you introduced me to, the “Apocalyptic Sublime,” pretty much sums up Edmund Burke’s idea of the sublime, “fearful joy.” But it really has some fascinating history and amazing relation to your work. Will you say something in relation to this.

The manifestation of apocalyptic art and its popularity came about during a period of domestic unrest, foreign wars and quite significantly–as it pertains to its relation to my work–anxieties towards major societal and environmental upheaval caused by the birth of the Industrial Revolution, which came to fruition around the same time. During the 18th century, interest in the Apocalyptic Sublime was expressed through what would have been ‘popular culture’ for the time: writing, poetry and art. Similarly, with widespread predictions of impending environmental meltdown as a direct result of the Industrial Revolution, during the last decade we’ve witnessed a return to imagery and stories depicting the Apocalypse with the film industry producing an unprecedented 50+ films illustrating various apocalyptic themes, many of which contain scenes which use similar techniques used by the painters in the 18th century to inspire the sublime.

Artists who were associated with the Apocalyptic Sublime envisioned catastrophic outcomes of this era, looking forward to what may be a result of the Industrial Revolution. We’re now sitting on the other side, facing its effect on the planet and ourselves. By way of the film industry, the Apocalyptic Sublime, or at least the popularity for consuming imagery depicting a catastrophe-ravaged planet has returned, almost certainly reflecting a like, collective anxiety towards a very uncertain future. My work plays into this, along with a number of other ideas and influences.

Ok the Creature From the Black Lagoon . . . it looooms in “Leviathan.” What is your worst nightmare?

I’ll share two actual nightmares that I’ve had which were equally terrifying. The first depicted the end of the world by way of an electrical storm. I was on a space station of some description, with the perfect vantage point to witness our planet being zapped with a wild web of blue electrical currents. The second, along a similar vein, involved the sun which ‘didn’t rise’. It was surprisingly peaceful and calm for a world which understood that it had hours left to live.

The Group of Seven. This is a hugely influential Canadian art group from the 1920s created what I imagine is a pretty hard body of work to deal with for a Contemporary Canadian artist working in what is seemingly the “landscape” genre. But you reference them quite naturally, or as a juxtaposition, unnaturally. Give us a clue into your thoughts on this . . .

As a Canadian artist it’s impossible to make work using landscapes without being part of that history. One of the interesting objectives of the Group of Seven was to showcase the beauty of the rugged, untamed Canadian landscape. I feel like I’m approaching things from the other side, after landscape–where I’m fabricating the wild, in a sense, to create a sensation of the sublime, which from my perspective has largely disappeared from the natural world. While I’m representing beautiful vistas like the Group of Seven, I’m also incorporating ideas about our experience and understanding of our highly mediated world where fact and fiction are barely decipherable and how we can no longer view landscape without being aware of how much we’ve drastically altered it, both physically and digitally.

Exiles of the Shattered Star, 2006, single channel high definition video, 30 minute loop

As a youngster from Colorado, of course I was privy to some of the most absolutely exquisite views in nature. In fact, one of those views, that of the Maroon Bells is perhaps one of the most downloaded screen savers in the world. So in fact, most people’s view of the famed mountain landscape is not a natural experience of the mountains, but a virtual one, that appears onscreen when activity on a computer has ceased. And according to Baudrillard “Simulacra” in a way means that the virtual experience at least equals, maybe excels, and perhaps exceeds the actual human experience. Do you think of your work as a critique of this or do you embrace it as a way of creating landscape terroristically, with our only tool left, digital manipulation?

I embrace digital manipulation as a tool to allude to the multiple, hybridized and seemingly un-navigable “realities” we now exist in. It’s not so much of a critique as it is acceptance. This is the world we live in; now what?

Which brings me to my last question. Often times when you make a piece, there is some type of Pilgrimage involved, like the Pilgrimage described in Michael Kimmelman’s Accidental Masterpiece chapter, “The Art of the Pilgrimage” in which the meaning of the Pilgrimage from Colmar to Marfa is elucidated upon. For you, traveling to places like Uncertain, Texas is just the beginning. You share the Pilgrimage with the viewer—a generous move as opposed artists whose work a viewer must/need to physically travel to, to see/view—like Smithson’s “Spiral Jetty,” Di Maria’s “Lighting Field,” or Judd’s “100 Aluminum Boxes.” How do you feel about bringing the Pilgrimage to the viewer as opposed to requiring the viewers’ dedication of time and effort in order to see the artwork/landscape in actuality . . .

That’s an interesting question. Most of the time I seem to be messing with pristine views which physically, I would never want to mess with. Working digitally also means that I can create impossible or improbable scenarios. I couldn’t transform the Lake District in England with raining meteorites, I don’t have the means of installing a vast field of holographic trees and with the most recent piece commissioned by Artpace, Leviathan, the phosphorescent life form in the water doesn’t exist.

Also, by removing location and all of the information associated with it which grounds perspective and understanding means that I can bring viewers into unfamiliar territory. I can transport people to another time, into possible futures or the distant past. In contrast to these strange, alternate spaces, I can ultimately make visible our current environment with some measure of hindsight.

Kelly Richardson’s work is currently on view in ‘The Cinema Effect: Illusion, Reality and the Moving Image’, Part 1: Dreams at Caixaforum, Barcelona, curated and organised by the Hirshhorn Museum and Sculpture Garden (through September 4, 2011) and ‘Videosphere: A New Generation’ at the Albright-Knox Art Gallery (through October 9, 2011). Please visit her website at www.kellyrichardson.net for further information on her work and upcoming exhibitions.