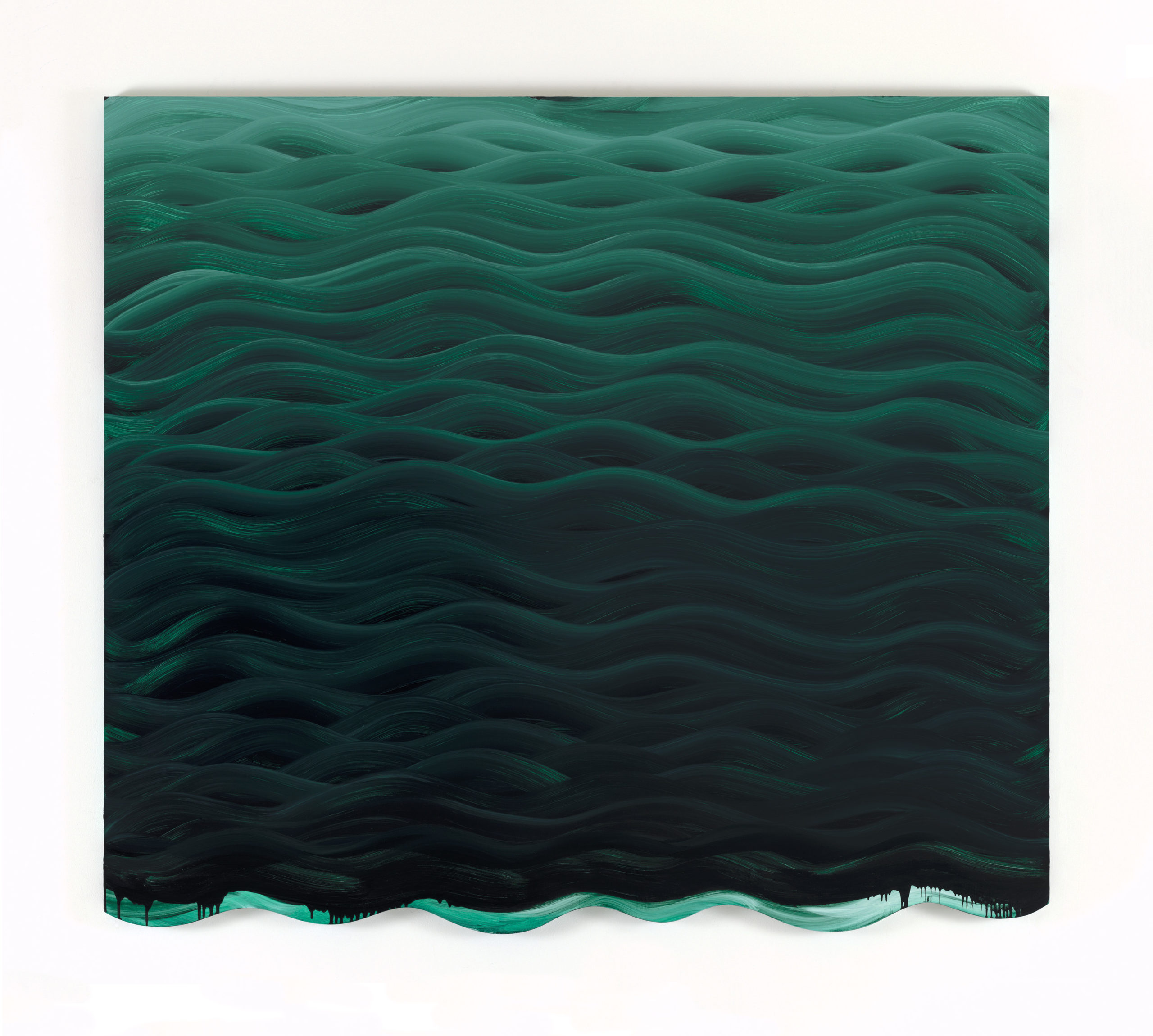

Karin Davie, While My Painting Gently Weeps no 2, 2019, oil on linen over shaped stretcher, 74 1/2 x 84 inches. Courtesy CHART, photo: Spike Mafford.

Karin Davie, originally from Toronto and now working between Seattle and New York, is a painter responding not only to the history of the practice preceding her time but also to her personal experience in the world. She was awarded the John Simon Guggenheim Fellowship Award in 2015 and was the subject of a major retrospective at the Albright-Knox Museum, Buffalo, in 2016, along with other institutional exhibitions both nationally and internationally. Her curated project

“Pushed, Pulled, Depleted & Duplicated” (with a poem-forward by John LeKay) appeared in issue #19 of zingmagazine. Davie’s solo exhibition “It’s A Wavy Wavy World” is on view through October 30 at Chart Gallery in Tribeca, New York.

Interview by Brandon Johnson

Upon entering the gallery I was met with two large scale paintings “While My Painting Gently Weeps No 2 & 4”. Each was immediately reminiscent of the surface of a moody and foreboding sea, which speaks to the title of this exhibition “It’s A Wavy Wavy World”. Did your thinking around the show change at all with the recent prolific flooding that occurred in New York as a result of the rainfall from Hurricane Ida?

The weather has become so unpredictable and dangerous because of global warming—but no, I didn’t think about this recent event in terms of my work. The imagery in these paintings comes from a deep ongoing interest in the history of art, the language of painting, issues of gender, identity, the body and landscape. My work doesn’t come from a reflexive reaction to something current in the news cycle. It’s a distillation of things that come from past and present history and my own lived experience. If I am drawn to some experience or idea, or am inspired to investigate something I don’t understand, these may develop enough urgency to make a painting. Things enter the work through a kind of osmosis. It’s filtered through my engagement with the world, sometimes pleasant, other times upsetting or enraging, and this takes time.

I currently live in Seattle, Washington. When I travel to my studio over a floating bridge which stretches across Lake Washington, I study the color and movement of the water and how it changes depending on the light and reflections. This experience of being surrounded by water, is an amazing sensation. I’m sure it has influenced my work. But I should also say, that water has an effect on me not only as an observed phenomenon, but as a metaphor for the forces of flow, unpredictability, transparency, the emotions, among others.

Moving further into the gallery there are four paintings featuring white squares in the middle surrounded by wavy brushstrokes and color gradients of blue, green, violet, orange and yellow. The former made me think of being underwater and looking to the surface light, while the latter resonated as cosmic or even supernatural transitory passageways, birth canals or “the light at the end of the tunnel.” Are these references on the mark, and how did you decide on the color palettes for these four paintings?

All the square paintings with intrusions have a slightly sly and humorous relationship to the metaphysical “light at the end of the tunnel” image. I wanted to play with this idea, and connect it to Minimalist painting, which is self-referential, emphasizing the medium and object-hood of the canvas, over a reflection of the outside world. These paintings push right up on representation and depictions of the body. This work is also rooted in personal experience, engaging with ideas about the self and identity. It’s a mash-up or smash up depending how you look at it (laugh). To me, they look like many things that convey transformation. For some paintings, I had a clear idea from the start what the color was going to be—certain hues of watery blues, hemoglobin reds or chlorella greens, for instance. I start by mixing up those colors, but the process allows for intuition. It’s not taken directly from observation or straight out of a tube. It may have origins from things I’ve observed in the world, and has to feel specific, but expands to involve organizing combinations of gradient colors to capture a mood or a feeling of temperature as well as creating optical movement, light and space in the painting.

In both cases, there is a primordial depth as relating to the sea (from which all life on our planet originates) and our own human watery origins of the womb. This is not only a space of physical abyss but also emotional, as watching the sea and contemplating our origins tends to have this effect. You’ve said the “wavy image” is a “recurring theme in my work and a metaphor for human emotions and life’s challenges–an obsession of mine.” Could you say more about this wavy image—as a symbol, a formal approach, and metaphor?

I can’t really tell you concretely why I’m compelled to paint waves or curving undulating forms, except to say that I’m driven to depict forms that relate to things in nature and the human figure. Geometric shapes contain and oppose this organic form. Perhaps we’ll find out in the future that these attractions or obsessions are all based on biology and genetics. Waves, by definition, are a disrupted transfer of energy and an action. The wave imagery can be metaphorical, but it’s not necessarily a thing itself, it becomes both a thing and an action when I paint. In my work an apparent landscape can morph into a bodily function or contour. It is this kind of “waviness” that is central to my expression. I’m engaged with the paint as a material and manipulate it into what I need to convey. My expression is embedded in the formal language of painting. In this particular work, it manifests in fields of wavy strokes in seemingly antagonistic relationship to the shaped format. It’s challenging and satisfying to work within this tight but limitless conceptual framework. These paintings have kinetic energy both optically and physically. These waves are essentially energy—they can destroy, or rejuvenate, possess darkness or light.

Karin Davie, In the Metabolic no 3, 2019 oil on linen over shaped stretcher 75 3/4 x 72 x 1/2 inches. Courtesy CHART, photo: Spike Mafford.

Many of the canvasses are shaped. What went into this decision? I’m particularly interested in those small semi-circle notches or extensions found at the bottoms of the In the Metabolic paintings…

When I first started this recent work, making wavelike marks around the inside edges of a large square, I observed my other hand securing the paper. I liked how the fingers appeared to become a part of the image, so the first drawings included a cut-out thumb shape intruding or protruding into the square. In both the drawings and paintings, the illusory image accommodates to the shape of the stretcher bar created by perverting the square. These first images led to other formal interventions determined by the shape and scale of different body parts or the canvases themselves. For instance, in the paintings “While My Painting Gently Weeps” and “Shape of a Fever” or “Down My Spine” the bottom or side shaped edges function like a cartooned version of the wavy strokes, which sets up a slight discontinuity. They purposely don’t exactly replicate each other’s form. In these works, the painted image is not co-extensive with the canvas shape, but is not unrelated to it either. It suggests a give and take of uneasy harmony with no easy answer over whether the literal or the pictorial has the upper hand.

The works on paper were made 10 years prior to the paintings. What led you to revisit and expand this body of work?

The large gouache drawings in the exhibition were made before the paintings, which is unusual for me. I don’t normally make comprehensive works on paper first. I see drawing and painting as conceptually linked but different enterprises. My process is that I make hundreds of doodles in sketchbooks, like automatic writing. Sometimes, I see an image in my mind, like hearing a song in your head, and then I quickly get it down as a doodle. If something interests me further from this process, then I will proceed to painting, sculpture, etc. But the paintings have a life of their own and everything still has to be worked out in the actual painting. This can take several years, as it did in this case. Things kept changing and shifting. It took a few years to settle on the scale and form. Although the gouache drawings in the show provided a foundation for these paintings, there were many steps in between. The materiality of oil paint differs from gouache, and the scale of the drawings differs from the paintings. This changes our physical interaction and perceptions about the image.