Photo: From the Hip Photo

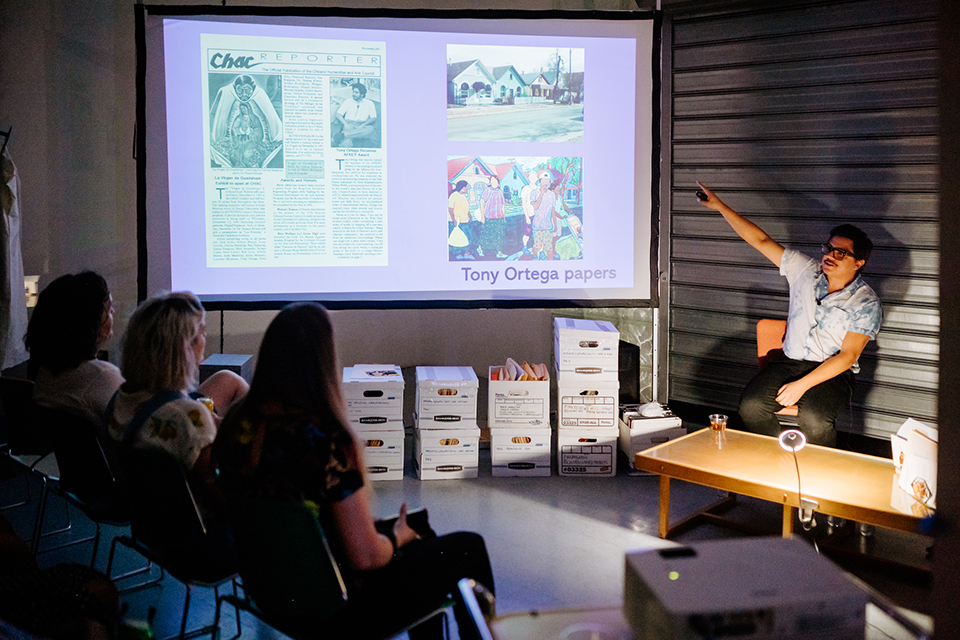

Josh Franco is an artist, art historian, and former zing contributor from West Texas. He has exhibited across Europe and the United States and will be publishing his first book, Marfa, Marfa: Rasquachismo and Minimalism in Far West Texas with Duke University Press later this year. Franco joined the Archives of American Art in 2015 as the Latino Collections Specialist and was recently appointed the Head of Collecting. On September 8, 2022, he sat down with Devon Dikeou for Archive Live—a series Franco conceptualized that puts artists in conversation with archivists and the public—to discuss her personal papers before they are sent to the archives in Washington D.C..

Interview by Paige Hirschey

The AAA has such an expansive mandate—to document the history of art in the United States—how do you determine which artists fit into this history? What goes into that process and who is a part of that conversation?

We have a thorough collections plan, most recently updated in July 2021. The plan is informed by our previous decades of collecting as well as rigorous discussion among staff (many, many drafts sent back and forth in the process). This collections plan lays out the intellectual framework and seven broad themes that help us organize our thinking when considering a new collection: lives of artists; research and writing about art; arts organizations; art market; patronage; art instruction and services; and miscellany. To quote the document, “While collections must have high research potential, as a national repository, the Archives seeks to represent the geographic scope, as well as racial and ethnic diversity, to build a representative picture of the visual arts in the United States.” I want to emphasize that this scope goes beyond the artists themselves and includes fabricators, critics, collectors, curators, and art historians as well.

I love the concept of Archive Live and sharing that exciting moment of discovery with an audience who might not be familiar with archival research. Can you tell us a bit about how the idea for those events came about?

I remember exactly how this came about! Sometime during my first couple of years at the Archives, when my role was Latino Collections Specialist, I realized how profound the experience of the collectors can be. We spend so much time working closely with accomplished arts workers poring over often quite personal documents. This inevitably brings a level of intimacy and deep historical knowledge that is not the typical classroom or museum experience, or even the reading room experience, where researchers have direct access to the materials, but not their creators. It felt very unfair that the tiny number of us who do this work got to have that experience, and I wanted to figure out how to share it with bigger audiences. Thus, Archive Live emerged as an idea, and I am happy to have conducted them with Paul Ramirez Jonas (our pilot and a Dikeou Collection artist!), Andres Serrano, Vincent Valdez, and most recently of course, Devon Dikeou.

Photo: From the Hip Photo

At our Archive Live event at the Dikeou Collection, you showed the audience the letter in which Marcel Duchamp offhandedly coined the term “readymade,” which underscored how important archives are in terms of preserving materials that may seem insignificant at the time but ultimately shape our cultural history. This impulse is also central to Devon’s practice, in the sense that she foregrounds the documentation of her own personal and professional history. Does that shape the way you’re deciding what material of hers will ultimately go to the Archives?

There is an extra layer of interesting complexity when collecting the papers of an artist whose medium is itself the art world. Like Devon in her practice, the Archives is concerned with documenting the social networks, notable figures, and institutions that give form to the visual arts. All of the records created by Devon—from her own practice, zingmagazine, and the Dikeou Collection—perform this function, so in a way, it’s like we are nesting the archive she and the whole Dikeou team have created within ours. Worlds inside worlds, is one way to think of it.

On a related note, I would imagine that Devon’s work is presenting some interesting questions vis-a-vis categorization. How do you differentiate “art” from “archive” in a body of work where they so frequently intersect? Is this something you’ve encountered before?

Yes, we encounter this with some frequency in fact. It’s often something the artist hasn’t had to think about before we begin conversations about the Archives. Our base policy is that it’s up to the artist first to determine what is artwork and what is archival material. Once they make that determination, we see how the identified materials fit or don’t fit into our collecting scope. Because Devon has put so much energy into documentation and thinking about this question herself, it’s actually relatively clear with her papers where the line is. That may seem counter-intuitive, but I think it’s a logical result of her practice; while someone who is, say, strictly a painter may just be thinking of this distinction for the first time, Devon’s practice, which takes documentation and administration as its central raw material, has led her to think about these questions deeply and for a long time. Unlike a painter who might be considering the status of their drawings in these terms for the first time ever, Devon has thought about these questions for quite a while, as they’re fundamental to her work.

Photo: From the Hip Photo

How does working with a living artist, whose practice is still evolving, affect the acquisition process?

It can be a double-edged sword. On the one hand, thinking again about Archive Live, it is invaluable to have the artist available to provide greater context for a collection, as we can document that additional information and make it part of the record, benefitting researchers down the road. On the other hand, undergoing this task while still active compels an artist to think of themselves in the historical long-term, which can do some strange things to one’s sense of self in time, not to mention one’s mortality. Again though, based on her practice, this kind of thinking seems to already be integral in Devon’s approach to making art, so I’m not worried about any kind of de-railing in this instance. In fact, I imagine the whole process could be incorporated into a Dikeou artwork in the future—what would Devon do with our shelving system? Our Finding Aids? Our Reading Room protocols? It’s conceptually rich, but also just a lot of fun, to imagine these possibilities.

Devon has worn many different hats in the art world, she’s an artist, editor, and patron, she’s worked in galleries and has an international network of art world contacts. How do you think this might inform the ways that future scholars will use her papers?

That’s exactly why I feel a sense of urgency around this collection. Some of our most frequently accessed collections are those created by figures who create worlds unto themselves through insatiable curiosity and a compulsion to document and gather ephemera. I am thinking of the Lucy Lippard papers and the Tomás Ybarra-Frausto Research Material on Chicano Art, which are perennially in the top 10 of most used collections, out of around six thousand. This is because Lippard and Ybarra-Frausto, when you look at their bios, dedicated their lives to building networks and continually connecting and re-connecting different nodes in those networks…and holding on to all the associated scraps of paper generated and gathered along the way. They are multivalent, with an entry point for nearly any aspect of art history in the United States someone might be thinking about. What’s striking in Devon’s case is that she is herself an artist, which is not the case with Lippard and Ybarra-Frausto. I am eager to see what uses the Devon Dikeou papers, zingmagazine records, and Dikeou Collection records are put to in the future. Devon is not only an artist’s artist, but an art historian’s artist too.