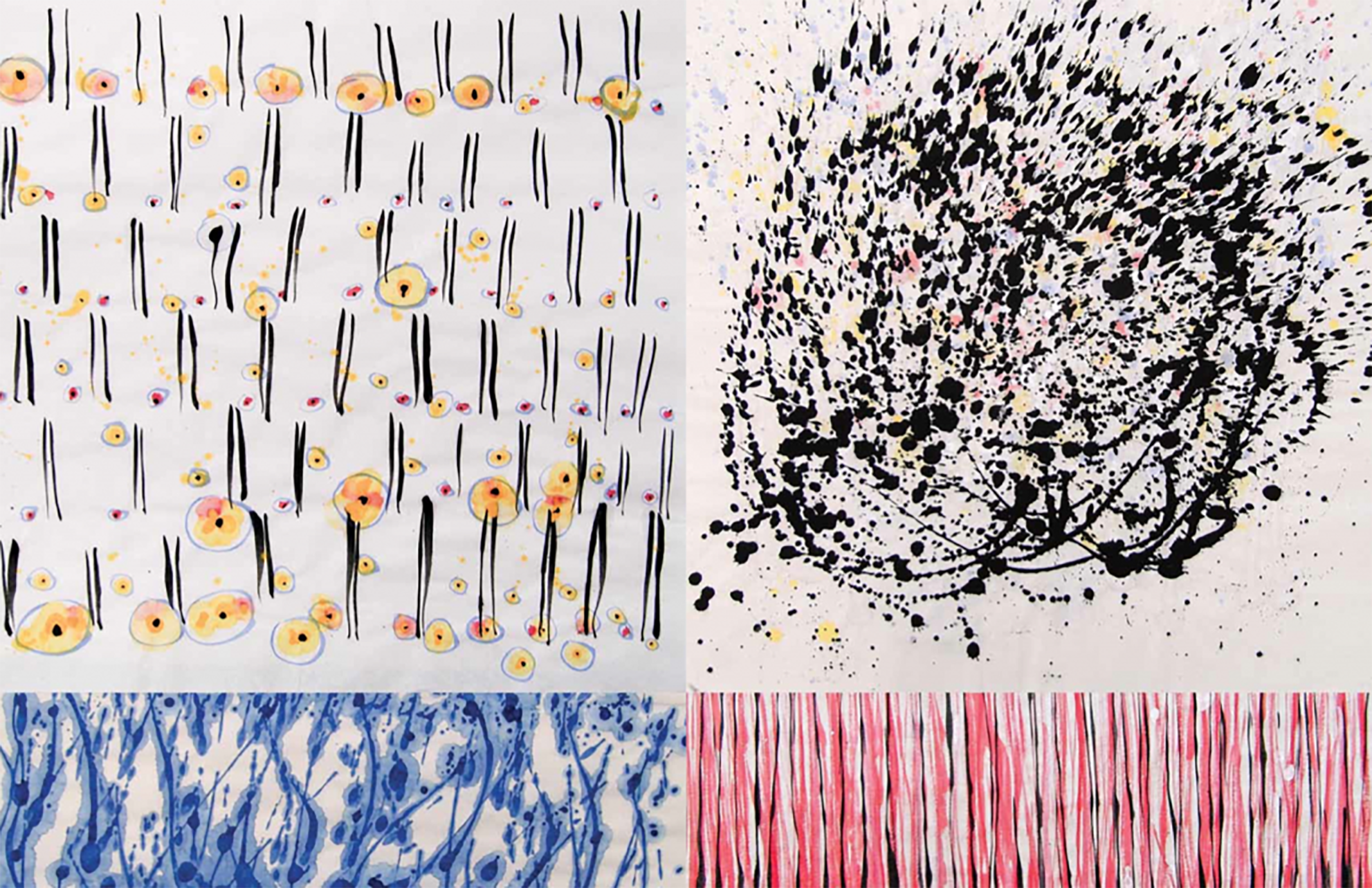

“Mix & Match: Watercolors from Cape Breton” spread from zing #23

From primordial human-scale concrete and cast sculpture made in various abandoned buildings in 1970s downtown New York, to Japanese brushes and watercolor on a remote coastal island, Jene Highstein‘s career has spanned decades, locations, and mediums. Most recently, the Cape Breton Drawings, which introduced color to his notoriously black palette. Moving from the terrestrial to the atmospheric, these works bring the viewer to the “magical landscapes” of Cape Breton, Nova Scotia. The Cape Breton Drawings are currently hanging in a solo exhibition at ArtHelix in Bushwick, Brooklyn. The drawings will also be featured in “Mix & Match: Watercolors from Cape Breton” in zing #23. In person, the man is a witty visionary, sharp of thought and full of personality—first hand experience of what this generation was about: achieving greatness, and having a great time doing so.

Interview by Brandon Johnson

What is the significance of Cape Breton to you personally?

My mother’s family is from Wilmington, NC and I spent my childhood summers on a beautiful white sand beach on the Atlantic. That experience was very moving. We would go to the beach early in the morning and spend all day in the sun swimming in the ocean and fishing off of a long wooden, and later, steel pier, which jutted far out into the Atlantic. We caught a myriad of fishy creatures, which we brought home for supper.

Meanwhile many of my friends had bought property in Cape Breton in the late 1960s, but I had never visited. Among them are my cousin, Philip Glass, and friends Bob Moskowitz and Hermine Ford, Joan Jonas, Rudy Wirlitzer, and Lynn Davis along with many others.

In 2002, on a lark, I took my son Jesse with me to have a look and fell in love with the place. It is very much like the NC experience in that the beaches are quiet, family-type places with few people, but the main difference is the remoteness and wildness of the landscape. The weather is relentlessly changeable, coming from one of four directions in turn so that in one hour the light changes dramatically. The color of the sky, sea, clouds; the fog rolling in and out, the rain coming and going all make for an amazing display of light and color and intensity of sun.

The Black Splash Drawings from 2007 (especially “Gesture (Nature)” and “Atmosphere”) seem to be precursors to the Cape Breton drawings. What initiated the Black Splash Drawings?

I have mixed my own black watercolors for many years but used them on traditional etching and other fine art papers. In about 2004 I began to experiment with what we call rice paper and the Chinese call Yuan paper. These are very different materials with extremely different reactions to the water element in the watercolors. Being in Cape Breton, so divorced from the NY art world and its taboos AND being a sculptor with no real inhibitions as to style and the history of painting, I was freed from all those constraints. I had used Chinese brushes for many years and am comfortable with their extreme sensitivity and ability to convey complex emotional charges. I began to use a kind of splash technique and was intrigued by it. That’s how it began to dawn on me that that technique could work. Over time I was able to become freer and freer with it and continue to do so.

What brought you to watercolor?

In the 1970s I used dry pastels for my black. In the 1980s I switched to black chalks, but by the 1990s I began to mix my own watercolors from bone black pigment which gave me the most dense velvety black that has become the basis of all my two dimensional works.

You have described your earlier sculptural work as not being based on natural forms but evolving in relation to nature, carrying natural associations. Can this also be said about the watercolors?

Yes, I suppose so. The watercolors came about from the intense saturation of my visual world when I went on long walks with friends in the remote areas of Cape Breton. These experiences were also reinforced by exploring the local beaches and bogs, which turn up equally unexpected encounters. The resulting watercolors are not so much impressions of these experiences but perhaps meditations on them.

Many of the pairings have horizontal lines dividing them—are these horizons?

The works are evolving. The more recent ones have a more defined reference to sea, sky, land and water but it’s a fluid transition because one’s experience of these areas is very fluid since they are constantly shifting, making it difficult to say which color or atmosphere would be associated with which . . .

What role does perception play in this series?

That’s an interesting question. In traditional Chinese landscape painting, as I understand it, the artist goes to the site and spends time there but doesn’t make any work. They return to their studios and indirectly interpret what that have experienced. Also, there may be elements of poetry or other language-based parts of the story, not to mention all the seals and comments of the subsequent viewers of the works.

My approach is also indirect in that I set up a studio in the dinning room of our house and began to work there with no particular plan. The work evolved every day on its own without too much intention on my part. It has become increasingly complex and dense in color, but I don’t think it has become more specific in reference to nature. My friend Hermine Ford looked at them and said, “I see, these are looking down, these are looking straight ahead and these are looking up.”

Your project in zing #23 features sections of the Cape Breton drawings paired with one another—4/5 one drawing and 1/5 the other—”mixed & matched” so to speak. Can you explain the thought behind this format?

“Mix and Match” seemed a good way to present a complex subject in a simple way. There is now a large body of the Cape Breton Watercolors, which span the simplest to the most complex ideas so I thought that I would scan through a lot of the images and see if somehow they could be paired into two sets of 4/5-1/5 images on facing pages, which would make sense. I’m happy with the results.