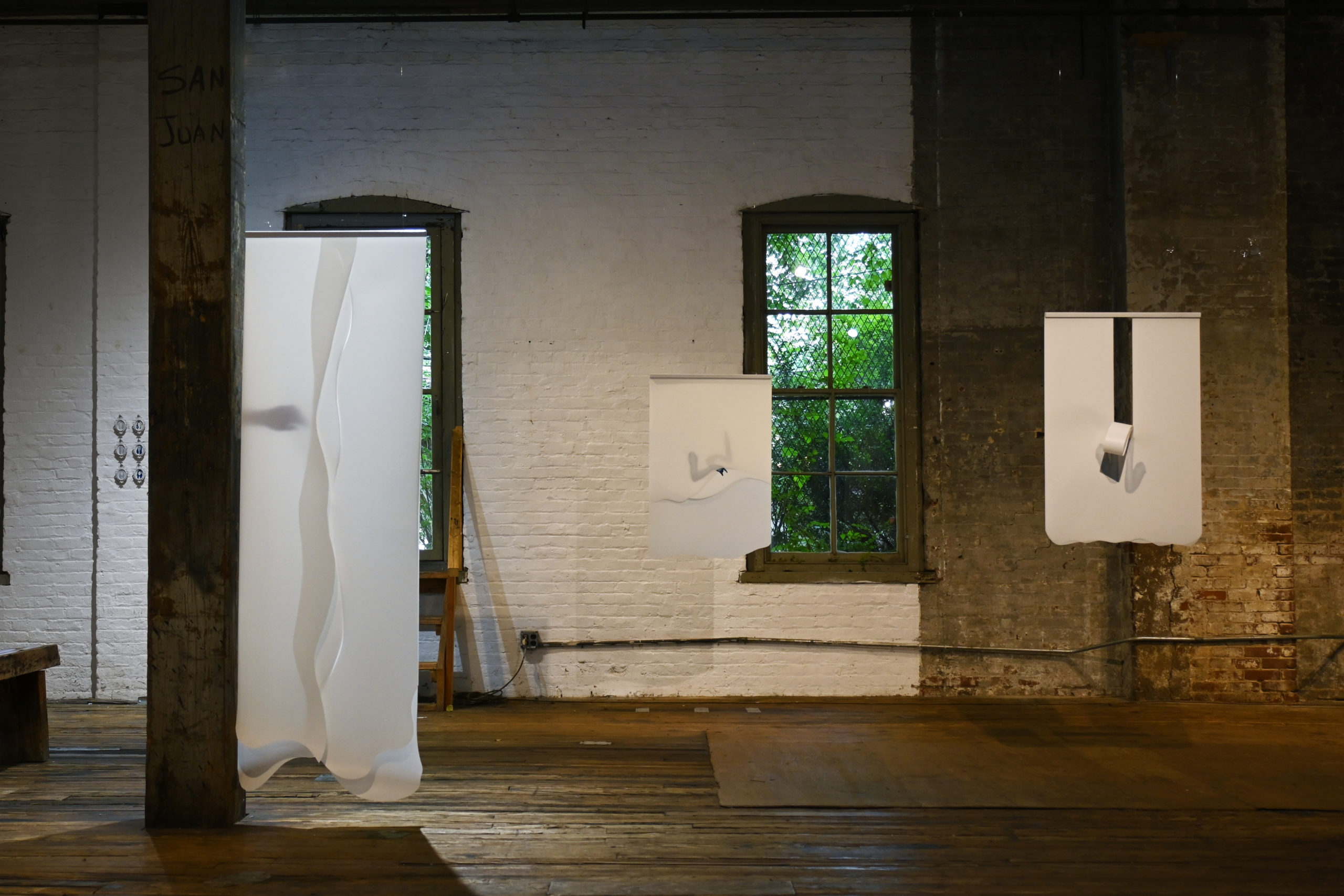

Heather Link-Bergman, installation overview

Heather Link-Bergman is a Denver-based artist, visual communicator, and educator. She is Affiliate Faculty of Art at Metropolitan State University Denver, a Partner of is PRESS (a publishing and design consultancy founded with Peter Miles Bergman), and Director of Intelligence of the Institute for Sociometry, an international artist collective and communications cooperative headquartered in Denver, CO. Her studio work takes form as collage, photography, performance, book arts, and social practice. Her work has been shown at MCA Denver, Center for Visual Art, MSU Denver, Chicago Cultural Center, ICA Baltimore, Printed Matter’s Art Book Fair, Vancouver Art Book Fair, among other venues. Most recently, Link-Bergman completed her MFA at School of Visual Arts in New York City, culminating in a thesis show “Liminal Forms” at The Invisible Dog Art Center in Brooklyn on view July 12 – 23, 2023.

Interview by Brandon Johnson

This body of work comes from your research on spirit photography. How did you become interested in the subject? Any findings that surprised you, or had a significant impact on the work?

Broadly, my art practice explores what’s missing—both literally and figuratively. So, spirit photography spoke to me because it’s all about seeing what is missing by photographing the inexplicable and unseeable, ranging from ghosts, spirits, thoughts, emotions, auras, etc. Through my research, I became interested in the modernist evolution of the photographic language of spiritual presence and the contradictions inherent in these images, how they simultaneously show what is and what is not yet.

While there were many surprises and synchronicities encountered in my research, the most meaningful finding for me was gaining a deeper appreciation of the social function and meaning of these types of images and how their primary purpose really isn’t to prove or disprove the existence of ghosts, but how they reflect our beliefs, anxieties, and/or doubts about the possibility of connection beyond life.

Heather Link-Bergman, Eternal Returns, 2023, Cyanotype on layered polypropylene paper, 38 x 25 inches

On a formal level over the last couple of years I’ve seen your work transition from pop-oriented graphic works to poetic minimal collages, now to a similarly minimal yet scaled up research-based cyanotype works on paper. What influences would you attribute to this progression?

The thread that connects this current project and my previous bodies of work is that they’re all collage in some form or another, and they are all about playing with the visual semiotics of specific genres of images or aesthetics. Spirit photography, as I see it, is a particularly fantastical and artful form of photomontage and collage. Early photomontage, or combination printing, was a laborious process where photographers carefully composited multiple negatives or exposures to compose a single constructed image. By the turn of the twentieth century, the spirits in spirit photography were often constructed from cut-outs taken from printed lithographic images from magazines. This is really where you start to see the visual motif of disembodied human heads, hands, or veils appearing as a visual short-hand for spirit. These observations drive many of the formal decisions I made with this work.

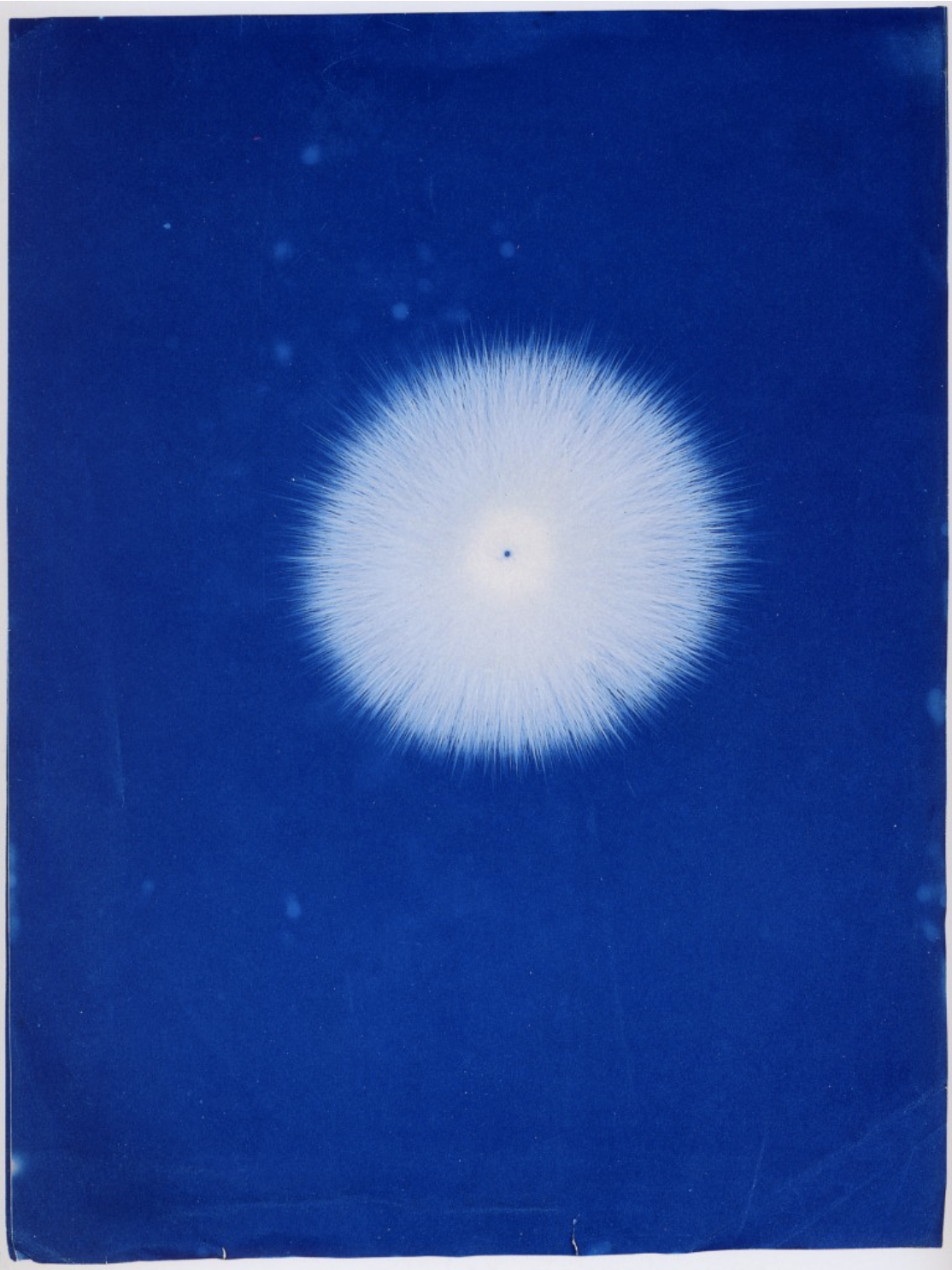

Hippolyte Baraduc, Electrograph of the vital fluid, 1895, cyanotype photograph

Why did you choose cyanotype for your printing method for this work? Is this a new technique for you?

Early in my research, I came across and was really entranced by a cyanotype photograph made by Hippolyte Baraduc in 1895 entitled Electrograph of the vital fluid. Baraduc’s “thoughtography” endeavored to depict what he believed was the universal fluid that flowed from all beings, living and dead. The term ‘universal fluid’ originated from German doctor Franz Anton Mesmer, who first developed these theories of universal magnetism, which became known as mesmerism. Baraduc was intrigued by Mesmer’s theories and hoped to use photography to document the existence of this universal fluid. Like all spirit photographers, Baraduc sought to make the invisible visible through his photography. Similar to more literal examples of spirit photography which feature a living sitter and a ghostly ‘other’, these photographs seek to represent what is present yet not recognizable or representable in our material world. Interpreting Baraduc’s photographic aberrations is like performing divination. We are left to imagine that these could be nothing but darkroom accidents or that they could be anything and everything.

The formal qualities of this image felt quite fresh to me and unlike many of the historical and contemporary cyanotype photography I’ve seen. It got me thinking about ways to use the medium I had written off. I was also excited about the conceptual possibilities of the distinctive blue color, which Yves Klein described as “the invisible becoming visible. Blue has no dimensions; it is beyond the dimensions of which other colors partake.”

While cyanotype is new to me, my approach to the medium is informed by my experience as a printmaker using an antiquated copy camera and halftone screens. I made all of my prints using my UV exposure unit, which is really designed for exposing printing plates. Getting the cyanotype emulsion to adhere to my chosen paper—polypropylene sheets—was a huge challenge. The paper is great as it looks perfectly flat and “untouched” even after taking multiple dips in water. What’s not so great is that it’s really hard to get any liquid, including cyanotype emulsion, to stick to it because it’s so water-resistant. I watched many would-be prints completely dissolve after they hit the rinse! This is where my historic research really came in handy, as I ultimately found my solution in the nineteenth century using a process similar to the gelatin or dry plate photographic process. I was so relieved to find a solution that I bought out most of the Knox powdered gelatin within the 2-mile radius of my zip code, just in case!

The ambiguity of Baraduc’s photographs is an interesting parallel to the way in which interpretation can be an important facet of contemporary art. While for Baraduc this ambiguity may have helped to shield against criticisms of veracity, for contemporary art it can open new potentialities beyond the artists’ original intentions. What role does interpretation play in your work?

This is a great question. Interpretation is part of any artwork, and it’s certainly something I consider a lot in my own practice. For my installation at Invisible Dog, I wanted to evoke a sense of the superterrestrial through my formal choices; I wanted everything to float. While making this body of work, I had written the phrase “hands suspended, awaiting, in an eerie blue twilight” in my sketchbook and I kept returning to that phrase as my aesthetic north star.

The spectral images and veiled forms in my work gesture towards themes of longing, absence, and spiritual connection. However, you do not need to literally believe in ghosts to understand haunting. Whether your ghosts are literal phantoms or just your ex, haunting in all its forms is the entry point for the viewer to engage with the themes in the work and an openness for them to form a more personal interpretation, should they choose to.

Heather Link-Bergman, Past Lives, 2023, Cyanotype on layered polypropylene paper, 20 x 16 inches

When considering interaction with the spirit world one often thinks of the “veil”—that invisible border which must be crossed to gain access to the other side. The works hanging from the ceiling (especially the tall rectangular one) evoke this notion with their layers and silhouetted hands and arms. Is there something more to the “veil” in these works beyond their physical representation?

Yes, there is definitely more to it, and you articulated it well in your question! There is a great deal of symbolism associated with the veil—it can represent what is disguised, hidden, or divided. Veils can shield or protect, and as a garment, they can take on many different meanings depending on the wearer and their religion, culture, or politics.

In my work, the veil is used as a metaphor to describe where we most closely confront the separation between life and death, consciousness and unconsciousness, or between our material reality and whatever may lie beyond it, i.e., ‘the world of spirit.’ For me, this project brings to mind the concept of ‘Viveka,’ which means discernment in Sanskrit and is the practice of using one’s discernment to see things clearly, as they truly are. Often Viveka is described as seeing the difference between the real and unreal, spirit from matter, and self from non-self. Viveka, in a sense, asks us to dwell on the threshold that mediates what is true and what is not. Spirit photography also asks us very similar things—to appreciate the interplay between the seen and unseen, spiritual and material, real and unreal—and to consider how those distinctions are not always as easy or straightforward as we’d like them to be.

Heather Link-Bergman, Parting, 2023, Cyanotype on layered polypropylene paper, 38 x 25 inches

The show takes place at the Invisible Dog Art Center in Brooklyn, an old factory space with wood floors and columns that evokes 1970s Tribeca and Soho, which is fitting for this body of work due to the association of spirits with older structures. It feels like this body of work could expand into a larger installation. Do you agree? What other kinds of spaces could you envision the work in?

The space was such a perfect counterpoint for the work; I am so glad to have had the opportunity to show this work at Invisible Dog. I don’t think it would have worked as well in the white cube of a conventional gallery. As for expanding into a larger installation, yes, absolutely, I agree! I see lots of potential to expand into not only a larger installation but a multi-sensory experience as well. My ideal scenario would be to take over a residence—perhaps even a whole house—and not only think about how to realize these photographic works on a larger scale but also consider expanding the presence and totality of the installation by creating new works like furnishings, housewares, and wallpaper as well as incorporating scent, sound, and temperature design into the overall presentation.