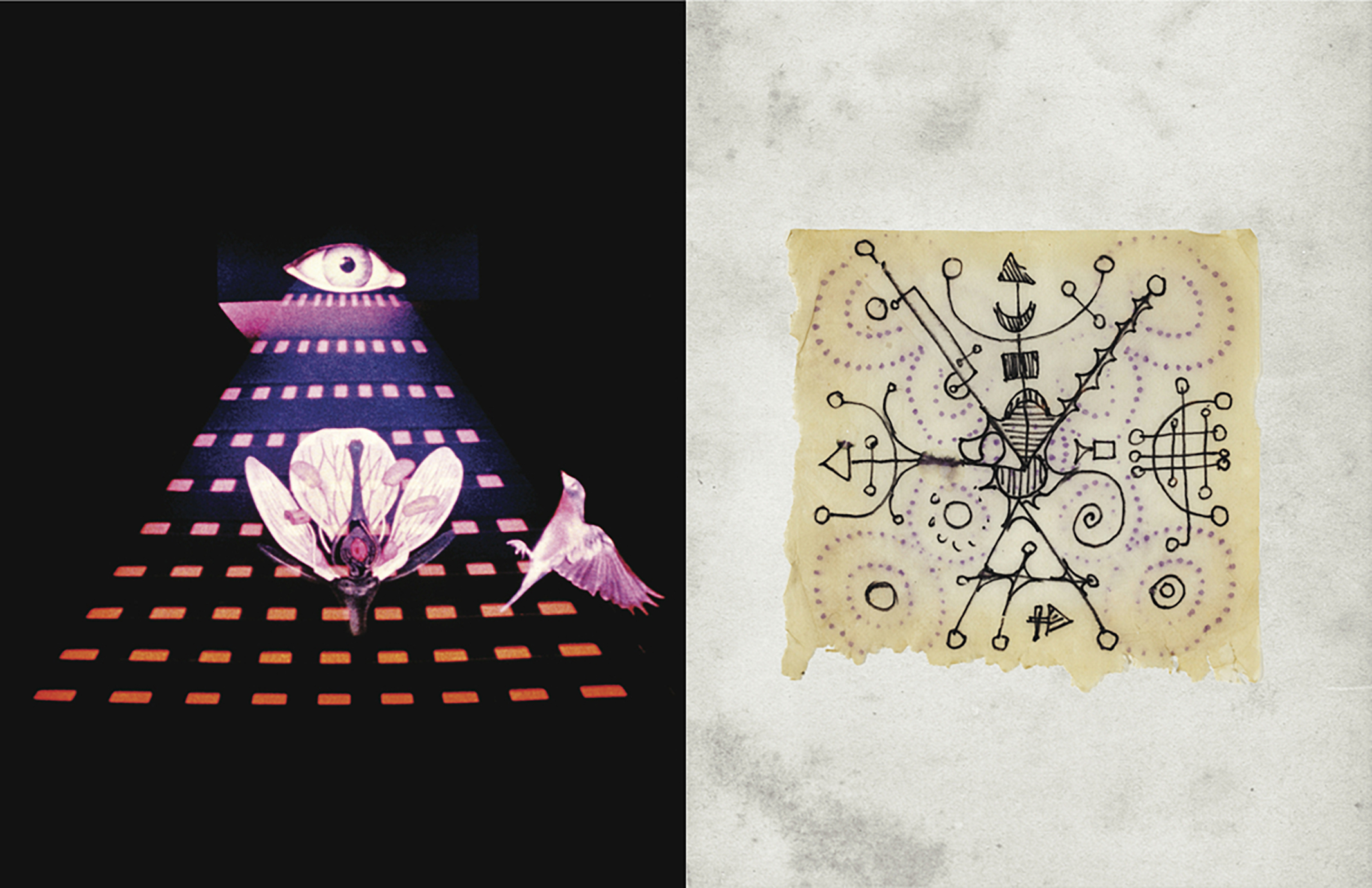

Spread from “A Strange Dream” with Still from Mirror Animations (1956-1957) on left and Untitled (c. 1977) on right

Art historian and newly appointed Dikeou Collection Director Hayley Richardson’s contribution to zing #24 “A Strange Dream” features the work of Harry Smith, a revered beat-era visual artist and experimental filmmaker, self-taught anthropologist, and explorer of esoteric knowledge. While Smith’s life’s work and interests were multi-faceted, from recording Kiowa peyote ceremonies to creating a Tarot deck for the Ordo Templi Orientis, to organizing an anthology of American folk music, his self-proclaimed primary role was that of a painter. Richardson’s past research on Smith has directed her toward this less explored (and less preserved) yet primary aspect of his work. Pulling from the collection of New York’s Anthology Film Archives, Richardson includes in her project four previously unpublished paintings and drawings among various stills from his more well-known films. “A Strange Dream” offers an entry point into the fascinating world of this cultural sage, while advocating for the primacy of his painting practice.

Interview by Brandon Johnson

You first discovered Harry Smith as an undergraduate student. Why has he stuck with you all this time, “making a racket in [your] brain ever since”?

It was a very formative time in my education, that last semester at University of New Mexico in particular. I was only taking three classes, one of which was a graduate seminar. I don’t recall how I even got into the class, but I was engrossed with the intimate, discussion-based format and how smart everyone was. At the end of the semester we presented our final projects and one girl did hers about occult and magical symbolism in the arts, and referenced this artist Harry Smith throughout her talk as a figure that was one of the last to truly understand, practice, and embed this knowledge in his work. She showed beautiful side-by-side images of alchemical Renaissance manuscripts with Harry’s abstract paintings and stills of his collage films and something just seemed to click for me, that this one artist was a conduit of sorts between the past and the future. As I progressed in my art history studies at University of Denver, I kept thinking about him and how everything he did was connected, his work in painting, drawing, film, music, spirituality, and anthropology, and it changed my way of thinking in a lot of ways. I started to see connections among the most seemingly unrelated things, which has had a tremendous impact on how I understand art and it makes many other things in my life so much more meaningful. I used the phrase “making a racket in my brain” because Harry had a bipolar personality and could be very manic/caustic, so I imagine him like this little gnome in my head getting into shit and stirring things up, reconfiguring my thought patterns.

This disparity in form is demonstrated in your project—works in different mediums stretch the boundaries of interconnectedness, but seem chosen for very specific reasons. Perhaps you could shed some light on the curatorial process—why did you choose the works that you did?

Harry had an incredible amount of artistic output, but sadly very little of it exists today. He destroyed or lost much of his art, and his landlords threw out most of it when he failed to pay rent while recording Kiowa peyote rituals in Anadarko, Oklahoma in 1964. This was an extremely distressful event in his life and marked a major downturn in his creative energy for about a decade. So part of the reason the images in my project seem disjointed is because so little is left of his artistic legacy. Some of his works exist in private collections; I am not sure how many. The rest of his paintings and drawings, of which there are about 50, as well as works on film, are housed at Anthology Film Archives in New York City. I was given a list of available digitized works from AFA and made my selections from there. I made a point of choosing works that had never been published, which are the four paintings. Although largely an “underground” figure, Harry was well known for his work as an experimental filmmaker, and the stills I chose are from his films that he was most recognized for, the main one being “Heaven and Earth Magic.” So it’s a mix of familiar imagery with some stuff that’s never been widely distributed before.

I’m particularly interested in the drawing on the torn fragment of paper. Can you speak more about how his work relates to esoteric sources? Is he working within a system of his own construction, or is the work more related on an aesthetic level?

I love that drawing as well. I saw it at AFA and I think it is drawn on a napkin, which is demonstrative of Harry’s compulsive urge to create utilizing whatever he had on hand. The drawing has a diagrammatic form, and diagrams played a major role in all of Harry’s work. When he was a young boy he would attend Native American ceremonies in the Pacific Northwest and create diagrams to correspond to the songs and dances, later he would have synesthetic experiences at jazz clubs and drew diagrams to illustrate the music, and he created elaborate diagrams while organizing and directing his films.

Diagrams are also widely used in hermetic imagery, and this particular image is like a fusion of those sources with patterns from his imagination. Similar markings also appear in the first untitled painting in the project. There is a book that came out in 1948 called The Mirror of Magic, which is a compendium of magical arts put together by Surrealist artist Kurt Seligmann. Harry was an avid book collector and I am pretty certain that he possessed this book because he seems to have pulled a lot of visual inspiration from it. In The Mirror of Magic is an illustration of celestial scripture from Athanasius Kircher’s “Oedipus Aegyptiacus” which is pretty much a hermetic alphabet composed of small circles connected with lines in various configurations. The connection between Harry’s drawing and the scripture shown in The Mirror of Magic is pretty direct, in my opinion, with Harry’s unique flourishes thrown in. Harry’s most important works have potent esoteric references, most notably his Tree of Life in the Four Worlds, which is based off the Kabbalah Tree of Life, and the album art for his Anthology of American Folk Music, which is full of that stuff, particularly Robert Fludd’s celestial monochord from 1616. His parents were Thelemites and his grandfather was a high-ranking member of the Knights Templar, and one of his earliest childhood memories was finding esoteric manuscripts in the attic of his house. He studied Kabbalah in New York under Rabbi Lionel Zirpin, was an ordained Gnostic bishop in the Ecclesia Gnostica Catholica, was a prominent figure in the New York branch of Ordo Templi Orientis, and his friends referred to him as the Paracelsus of the Chelsea Hotel. Harry’s engagement with the esoteric in his art goes beyond just aesthetics–he lived it.

Your title “A Strange Dream” is very apt for this selection. Does it derive from a specific source?

“A Strange Dream” is the name of Harry’s very first film, which he created by painting directly on the film circa 1946-1948. He started making these films when he was first introduced to jazz and wanted to illustrate the music. This particular film was originally intended to go with the music to Dizzy Gillespie’s “Manteca,” which he also made a painting after but no longer exists. If you play the song and video at the same time they synch really well. I think it’s a good title to introduce the project, as it is pretty strange and dreamy, and seems an appropriate description for Harry’s life in general.

Have you done any other work/projects involving Harry Smith?

I wrote my master’s thesis about Harry’s paintings. There is a lot of information out there about his work in film and music, and people would reference his paintings with admiration but no real academic research had been applied to them. He even said his “primary occupation” was as a painter, so it seemed like a necessary area to investigate further.

Interesting that he would say his primary occupation was painting, especially since he seemed to have destroyed many of his own paintings and was involved in so many other fields. Do you have any further insight onto why he would consider himself as such?

It was in a 1965 interview with film historian P. Adams Sitney when Harry said, “I was mainly a painter. The films are minor accessories to my paintings; it just happened that I had my films with me when everything else was destroyed. My paintings were infinitely better than my films because much more time was spent on them.” (http://www.ubu.com/sound/smith_h.html)

Yes, he did destroy, give away, or abandon some paintings, but it was in 1964 that his landlords trashed everything, except the films which he had with him or had already given to Jonas Mekas at Anthology or Allen Ginsberg for safe keeping. He went to the Fresh Kills landfill everyday to look for them. Harry started painting at a young age; he painted directly on film, and made paintings to map out the complex projection schemes for his films. Painting was the generative activity for his creative pursuits in other media.

Any plans for future Harry Smith curatorial projects?

I’d like to get my research published somewhere, just haven’t had the time to do that. It would also be a real treat to present a screening of his films with a live jazz band to provide the soundtrack. Perhaps someday at Dikeou Collection . . .

Speaking of which, you recently took over as Director of the Dikeou Collection. What can we expect there moving forward?

I started as an intern at Dikeou Collection in 2011 and am honored to be the new Director. I have learned so much and seen the collection grow immensely over the years. My main priority is maintaining the upward momentum with programming, community engagement, and exhibitions. Nothing has been formally announced yet so I won’t say too much, but there are some big projects in the works for 2016 and 2017. The collection has been open to the public for 13 years, and with the current projects we have on the table I see that we’re transitioning from a period of establishment and growth into building a real legacy, so I am hoping to introduce some new concepts that can be carried on long-term.