Ester Partegàs at opening of “Steady” at Marfa Ballroom. Photo by Sarah M Vasquez.

Ester Partegàs is an artist and educator born in Barcelona, and based in New York City while being a part time resident of Marfa, TX and Barcelona. Her work has been shown at Fundació Joan Miró (Barcelona), Essex Flowers (New York City), Pure Joy (Marfa), The Drawing Center (New York City), The Museum of the City of New York, MACBA Barcelona, SculptureCenter (New York City), Whitechapel Gallery (London), among other venues. She was recipient of the 2022-2023 Rome Prize, a 2004 Joan Mitchell Foundation Grant, and has been an artist-in-residence at Chinati Foundation. She’s been faculty at Yale School of Art, Virginia Commonwealth University, SUNY Purchase, and Parsons School of Design. She was recently part of a two-person exhibition with artist Michelle Lopez at Ballroom Marfa titled “STEADY” (April 17 – September 8, 2024), organized by Daisy Nam. The exhibition will travel to CCA Wattis Institute for Contemporary Arts in San Francisco, opening January 21, 2025.

Interview by Devon Dikeou

Ester Partegàs, Twilight (laundry baskets), 2024. Courtesy the artist and Ballroom Marfa. Photo by Heather Rasmussen.

So “STEADY”. . . Your show at Marfa Ballroom (with Michelle Lopez) in my mind is an exploration of the mundane and balance . . . Can you speak about your relationship to the mundane, balance and your work’s juxtaposition with Michelle’s . . .

There are many juxtapositions between my work and Michelle’s. All the works in “STEADY” play with balance in a seemingly precarious way. Michelle’s ROPE PROP REVERSAL (2023) held upright through a careful balance of tension and counterweight, for which she has torched the steel to make impossible movements and bends. The main body of my sculpture Knots (2024) is held up in the air by five unattached rebars, and Twilight (2024) as much as Host (2024) needs other collaborative bodies to stand up. The sense of imminent collapse is palpable. For both of us, balance is only real and believable when it integrates contingency and vulnerability and accepts another’s support. Daisy Nam, the curator of the exhibition, explains in her introduction that balance here is not an independent act but interdependent.

The mundane is the position I want to speak from. The present continuum that’s right here right now that pervades everything all the time. The mundane allows me to demystify and present a different perspective on what has been deemed important and memorable. Both Michelle’s and my work render power structures vulnerable and propose a material landscape that is tender, alive, and playful, instead of separated and authoritative. Take into account that our embodied experiences as women artists, mothers, and immigrants also play a big role in our works.

Mundane are also my materials: cardboard, fabric, wool, bricks, steel rods, and paper mâché; specifically, for the “laundry basket” series. I wanted to make sculptures without a pre-designed final form but provoke a form that can reveal itself while making, by articulating discoveries, by assimilating contradictions. I wanted to work like a painter works. In this process, the materials are forced into a cycle of destruction, deterioration, and mending, giving the work a vital experience. For these reasons, the materials had to be easy to manipulate, not precious, malleable. My wish is for the viewer to sense that working.

Ester Partegàs, Knots (laundry baskets), 2024, and Michelle Lopez, SINGLE LINE, 2023. Courtesy the artists and Ballroom Marfa. Photo by Heather Rasmussen.

Also, I feel like your work, and this is for a long time now, is really engaged with moments. Much like Vija Celmins. Bringing the moment to the monumental . . .

I would say attention. Or moments in the sense of the small and ephemeral. Of something that is ever present but invisible at the same time. I love Georges Perec’s neologism of the “infra-ordinary.” The “infra” points to yet another level of depth of something we assumed had touched ground, or had nothing else to offer.

You won Rome Prize 2022/2023 and started a series of drawings of bread . . . Some of which seem to come from that Rome body of work are in “STEADY”. . . Drawing the bread super hyper-realistically and then taking it back to our other hyper-reality by putting/attaching stickers that act as emojis to the drawings . . . That surface gesture in the real form of course changes the spatial integrity of the realism . . . Can you speak about that . . .

The realism of the bread seemed necessary to blur bread and stone together. The drawings portray slices of bread that behave like stones: piling up, balancing, and building shapes. The pencil drawings looked very precious, maybe too precious, a bit archaic, or old, and I had to bring them to the present. The mundane for me is irreverent because it is direct and can’t hide, it presents itself as is without filters. Part of the irreverence is that it leaves interpretation directly onto the viewer, the mundane hasn’t had time to be managed.

The stickers came about via colored tape, which simply was what I had in hand to temporarily put together several 8.5” x 11” sheets of paper to produce a larger drawing surface. And it was only later that I realized that was exactly what I was looking for. Since my daughter, 8 years old, has access to my studio, her materials—colored tape and stickers—are around. Both the tape and the stickers allowed me to structurally bring the sheets of paper together in a similar way the sculptures are put together from different fragments. Again, an interdependence. And by structure, I mean something that holds things together in a material and also immaterial way, like the little messages we send to family and friends throughout the day expressing affection and care.

Ester Partegàs, knead, penetrate, let go (cat spaceship donut), 2024. Courtesy the artist. Photo by Heather Rasmussen.

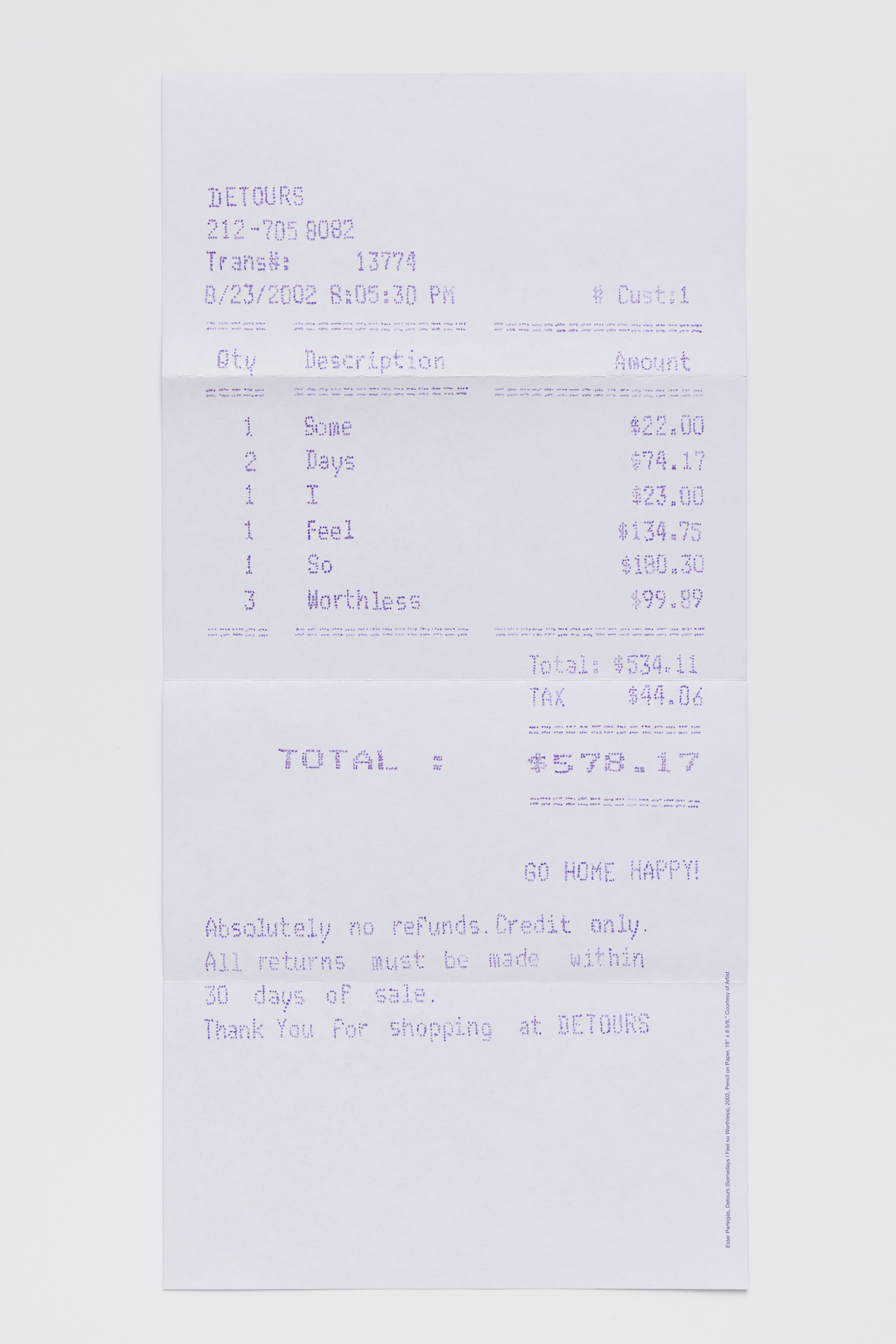

In issue 17 of zingmagazine we published a poster of a drawing you made, which subsequently became the series, “Detours”. . . It was a brilliant super-realistic drawing of what one could potentially buy at the store that day . . . A receipt, the kind most people crumble up and throw away . . . Or just toss into a pile of stuff to deal with later . . . that bit, that generally escapes one till the beginning of April and the accountant . . . Purply in the way receipts are . . . However, looking carefully reveals it’s not dish soap or toothpaste but abstract ideas . . . Buying some notions/sundries/household goods and saving its receipt, a most beautiful and complete gesture . . . But buying thoughts/happiness/unhappiness/the metaphysical while maybe unattainable or attainable may also be equally fulfilling or unfulfilling . . . And that body of work—“Detours”—informs the commemoration of life’s banality . . . Much as “STEADY” does . . . Thoughts . . .

I work from the assumption and proposition that nothing is banal. Behind each small act there is a huge emotional investment. When you buy a $2.00 chewing gum, you might think “I have bad breath,” “I feel anxious,” “I need something in my stomach before dinner time.” When I make these drawings, my exercise is to listen carefully to the many thoughts my brain produces regarding that little action. The series is called “Detours,” referencing the psychological detour we take, like nothing is a straight line. If you make that observation within yourself, I am sure you will be able to translate every desire into an actual purchase, into a receipt. Besides all this, I find paper receipts per se quite beautiful, literally like drawings of the everyday. Unfortunately, the non-digital ones are slowly disappearing and soon will be non-existent. I recommend spending some time looking at the different fonts, ink colors with their mistakes and blots, read the amount of information disclosed as a testimony of that precise moment.

Ester Partegàs, Detours (Somedays I Feel So Worthless), 2002, poster published on occasion of zing #17

It leads to my last question about the sculptural enlargements/fragments of laundry baskets highlighting their psychedelic melting quality . . . Certainly tackling issues of home and life in general, but on a formal level also leads to questions about space, sculpture, line, even painting. Frank Stella made a career of addressing these formal issues. In the ‘80s he influenced the whole scene of artists—his contemporaries at the time of his second retrospective at the MoMA—as well as other generations from Rachel Harrison, Isa Genzken, to Jessica Stockholder. . . The works in “STEADY” address issues of painting and sculpture and our recent history both formally/visually . . . Can you speak more about your work in a more formal sense . . . Because I think there is a real relevance to Stella’s critical treatise Working Space and the generational work that came out his practice/ideas in your work. . . And the work in “STEADY” . . .

I am glad you are bringing painting into the conversation. The color in the laundry basket series is informed directly from the commercial laundry baskets themselves. They mostly come in pastel colors with implications of softness, quietness, and order in an attempt to idealize the domestic of course. I am interested in working with those assumptions and then working on those colors attaching them to other moods. I want to make them seductive and also repellent at the same time, I want to make them scream or act bitter. I modify the intensity of the color by adding other pigments, dirtying them, or layering them. As far as your mention of Stella, I need to clarify that growing up in Spain we had other influences. Thus, I have not read Stella’s book, but now I am eager to hear what you have to say about it. The lineage I received ran through modern giants like Dalí, Miró, Picasso, and Tàpies, always presented like larger-than-life characters I was completely mesmerized with. This is a simplified version of my history, but for the sake of brevity, I can say that for me it jumped directly to Warhol, Beuys, and the ‘90s, where I encountered Jessica Stockholder. Both Warhol and Stockholder have been huge influences especially when it comes to dealing with consumer objects. I can trace a before and after in my own working and thinking. With Jessica’s work, I had never seen the freedom objects and colors could produce together. The work exuded energy, aggression and playfulness, while also standing as really good painting and sculpture in a way that is fascinating and unfathomable in the large installations.