Installation view: Elmgreen & Dragset, It’s Never Too Late to Say Sorry, Aspen Museum, 2018. Photo: Tony Prikyl

Here we speak with two contributors to zing #25 who currently share an additional curatorial crossing—Elmgreen & Dragset’s installation It’s Never Too Late to Say Sorry at Aspen Art Museum (on view through May 19th, 2019), where Heidi Zuckerman serves as CEO and Director. The work itself is a display case containing a polished aluminum megaphone on a granite pedestal, which is used daily at noon by a man to shout the phrase: “It’s never too late to say sorry!” This installation and their zing project “Variations of Blue” exemplify the combination of sculpture, installation, and performance characterizing the practice of Michael Elmgreen & Ingar Dragset, who have worked together under the name Elmgreen & Dragset since 1995. Heidi Zuckerman joined Aspen Art Museum as Nancy and Bob Magoon CEO and Director in 2005 and as Aspen Art Museum celebrates its 5th anniversary in the current Shigeru Ban building, the Crown Commons have become an architectural platform for public engagement—a context in which Elmgreen & Dragset thrive. With her zing project “…some fragment of a dream” we gain insight into what may be the beginnings of Zuckerman’s curatorial impetus, or at the least, an activation and step along the way.

Interview by Brandon Johnson

It’s Never Too Late to Say Sorry is a simple yet powerful relational gesture occurring in a public forum. How do you—both the artists and curator—feel that this work relates to its current context of Aspen, Colorado?

HZ: I am interested in Ho‘oponopono, a Hawaiian practice of forgiveness and reconciliation. There is nothing more powerful than accepting an apology that you have not, and likely will not, receive. The placement and performance of this work in front of the Aspen Art Museum, as we approach the fifth anniversary of our building, is connected to this notion.

E&D: Guilt is global—everyone has something to say sorry for. We’ve previously shown this work in cities ranging from Rotterdam to New York to Munich, and now, Aspen. A lot of influential people visit Aspen, and we hope the work prompts everyone to reflect on the potential power of an apology, whether it be related to civic issues, personal relationships, or something else entirely.

A megaphone is a very analog method of amplifying one’s voice. There are not many town criers these days. Why choose this method of communication in our contemporary context?

E&D: Today, we are bombarded by a constant stream of disembodied messages that appear on various screens in the form of tweets, text messages, news reports, emails, notifications, comments, etc. The megaphone allows the physicality of an actual human body and the sound of an actual human voice to come together and be amplified in this real-time performative action, asserting the body in space and underlining the significance of the phrase that is shouted. As you mentioned, the town crier is an extremely outdated method of communication; it starkly contrasts with all the instantaneous options we now have at our fingertips. The work harkens back to this old way of transmitting information and suggests that even though certain methods have been eclipsed by new ones, there are still some messages that endure. As an object, the megaphone is closely associated with concepts like protest, authority, disruption, and control—using it in this context hopefully brings these layered associations to the artwork as well.

HZ: I am really interested in punctuation, and the megaphone is an incredibly elegant exclamation point!!

Heidi, when did you first encounter the work of Elmgreen & Dragset, and what appealed about their practice as a curator?

HZ: While I can’t recall the first time I came across their work, two significant experiences were my visits to Prada Marfa (2005) in Texas and their Danish Pavilion installation, The Collectors, at the Venice Biennale in 2009. I am drawn to work that feels timely and relevant, and both of these installations took familiar things and offered new, surprising perspectives.

Elmgreen & Dragset’s project in zingmagazine #25 “Variations of Blue,” curated by Maureen Sullivan, focuses on the motif of a swimming pool in as documented in various installations of your work going back to 1997. What is it about pools that has kept you engaging with this subject over the years?

E&D: We’re fascinated by both the aesthetics and the social significance of pools. The idea of a private pool has in our post-war Western culture been a symbol of social status for those living in the suburbs. We first challenged this narrative at the Venice Biennale in 2009 with our work Death of a Collector, which depicted a wealthy art collector floating face-down in his pool in front of the Nordic Pavilion. More recently, our exhibition This Is How We Bite Our Tongue at the Whitechapel Gallery (2018–19) marked the first time we used a public pool in our work. That installation, entitled The Whitechapel Pool, dealt with the loss of civic space and shared values through the portrayal of an abandoned pool. We created a fictional history to accompany the pool, detailing its rise as a famed public amenity that later lost government funding and then got sold off to a private developer, who was about to turn it into a membership spa. Through our research for that show, we learned more about how the decline of public pools in the UK mirrors other cultural shifts in the past decade.

Back in 1997, one of our first sculptural works, Powerless Structures, Fig. 11, was a diving board that penetrated a panoramic windowpane at the Louisiana Museum, which is located by the sea north of Copenhagen. Inspired by David Hockney’s famous painting A Bigger Splash, the work also addressed the discourses of the late 1990s around the inclusion and exclusion of queer identities and minorities within established (art) institutions—the diving board being stuck midway between the inside and the outside of the museum. Nearly two decades later, in 2016, we began making a series of diving boards that are presented vertically and engage with the tradition of Minimal sculpture and stripe paintings. That same year, Public Art Fund presented Van Gogh’s Ear, our public sculpture of a garden pool—also displayed vertically—at Rockefeller Center in New York. It looked like the pool had been taken out of the showroom and put in this unfamiliar, urban context. The pool theme appeared again in Zero, our work for the 2018 Bangkok Art Biennale, which is a schematic interpretation of a pool reduced to its essential components, a hollow oval outline of the pool shape with a diving board and a ladder. We keep working with pools because we find them to be endlessly interesting subjects to consider on many different levels.

Spread from Heidi Zuckerman’s “. . . some fragment of a dream,” zingmagazine #25

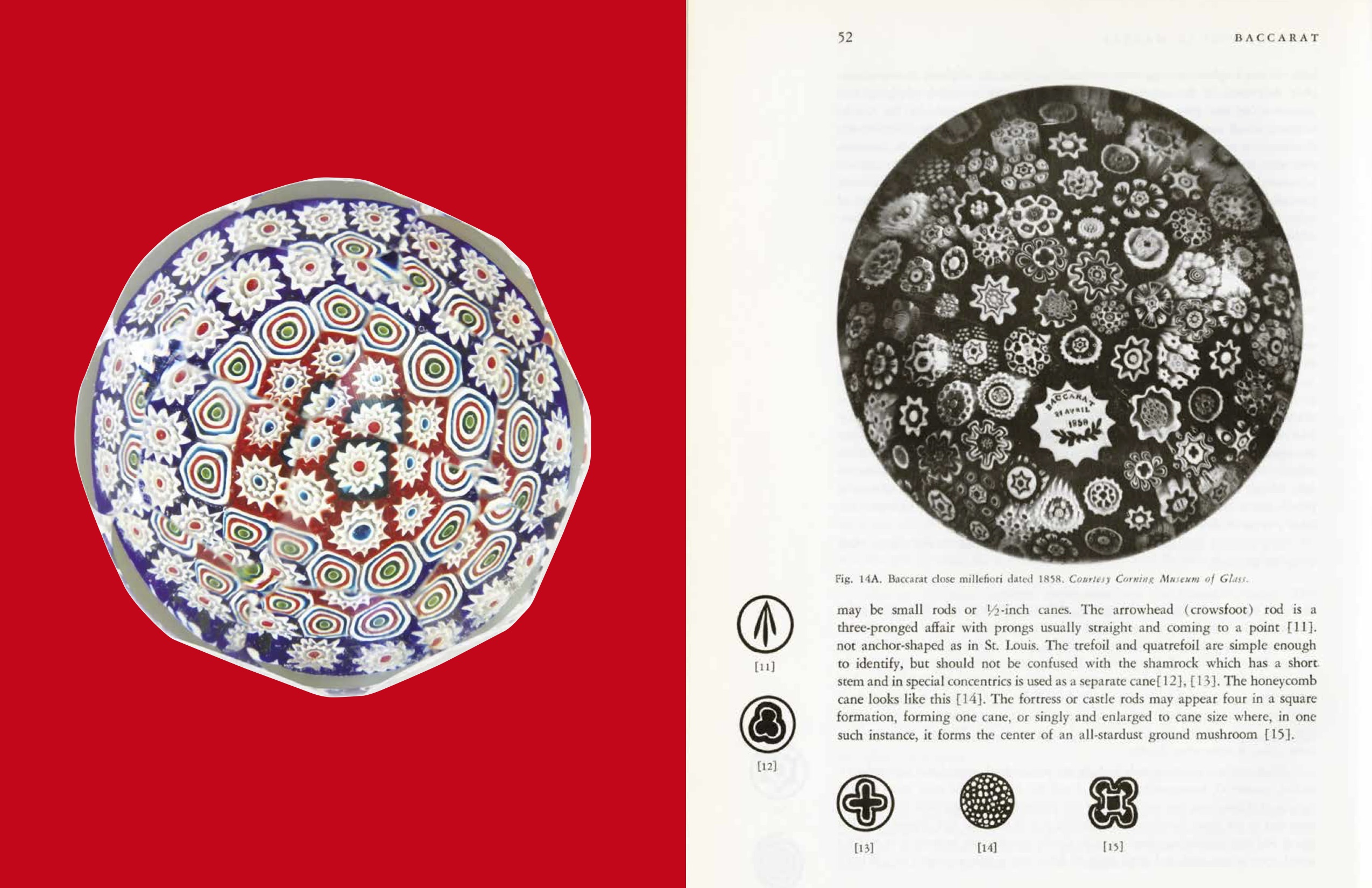

Heidi your project in zingmagazine #25 “. . . some fragment of a dream” is centered around a collection of paperweights your grandmother gifted to you. This collection became more significant after a visit to the Art Institute of Chicago, where objects like these were presented in the context of fine art. Can you further describe this satori at the Art Institute? And how have your views on collections and collecting evolved over the years (if at all)? Finally, do you still collect paperweights?

HZ: The event you are referencing happened when I was a senior in college and visiting Chicago for the first time. The satori there were linked to a much broader awakening tied to my realization that I wanted to pursue a career in art. A conversation ensued soon thereafter with my parents when I informed them of my new path. Using Joseph Campbell’s Hero’s Journey terminology, I now understand that time as my “burning of the boats” moment.

Once one catches the collecting bug, it’s virtually impossible to shake. So, yes, I still collect paperweights and, interestingly, in the last few years, people have started to gift me them as well. I also collect chairs, blue-and-white ceramics, books, shells, and, not surprisingly, contemporary art.

Finally, any forthcoming projects in the works you are particularly excited about?

HZ: The next installation on the Aspen Art Museum Commons (where Elmgreen & Dragset’s work is currently installed) is by Erika Verzutti. Verzutti will create a large-scale bronze Venus—an extension of her recent smaller sculptures incorporating organic forms that depict the Roman goddess of love, sex, beauty, and fertility. Her Venus will be inverted in a headstand. As an almost daily practitioner of yoga and a committed headstander, I am particularly excited about this upcoming project!

E&D: We have several exhibitions opening in March in Asia: two gallery solo shows and a project at Art Basel Hong Kong. We’re having our first-ever show at Kukje Gallery in Seoul, entitled Adaptations, and we’ll be presenting new works in two sections of the gallery. One section will house works that incorporate familiar elements from the public sphere, while the other will display works that focus on the human body, from abstract to semi-abstract to figurative representations of the body and some of its intimate spheres. At Massimo De Carlo Gallery in Hong Kong, our exhibition Overheated will transform the gallery into an abandoned, underground boiler room with industrial tubes of various colors and sizes crisscrossing throughout the space, along with a number of sculptural works within this basement-like environment. And at Art Basel Hong Kong, we’ll be presenting City in the Sky in the Encounters sector. It’s an imaginary city in a scaled model, installed upside-down.

After that, we’re curating a group show inspired by our favorite painter of domestic interiors, Wilhelm Hammershøi, opening at the National Gallery of Denmark in Copenhagen in April. We’re also planning a big show at the Nasher Sculpture Center in Dallas that will focus on our sculptural works, and that opens in September.