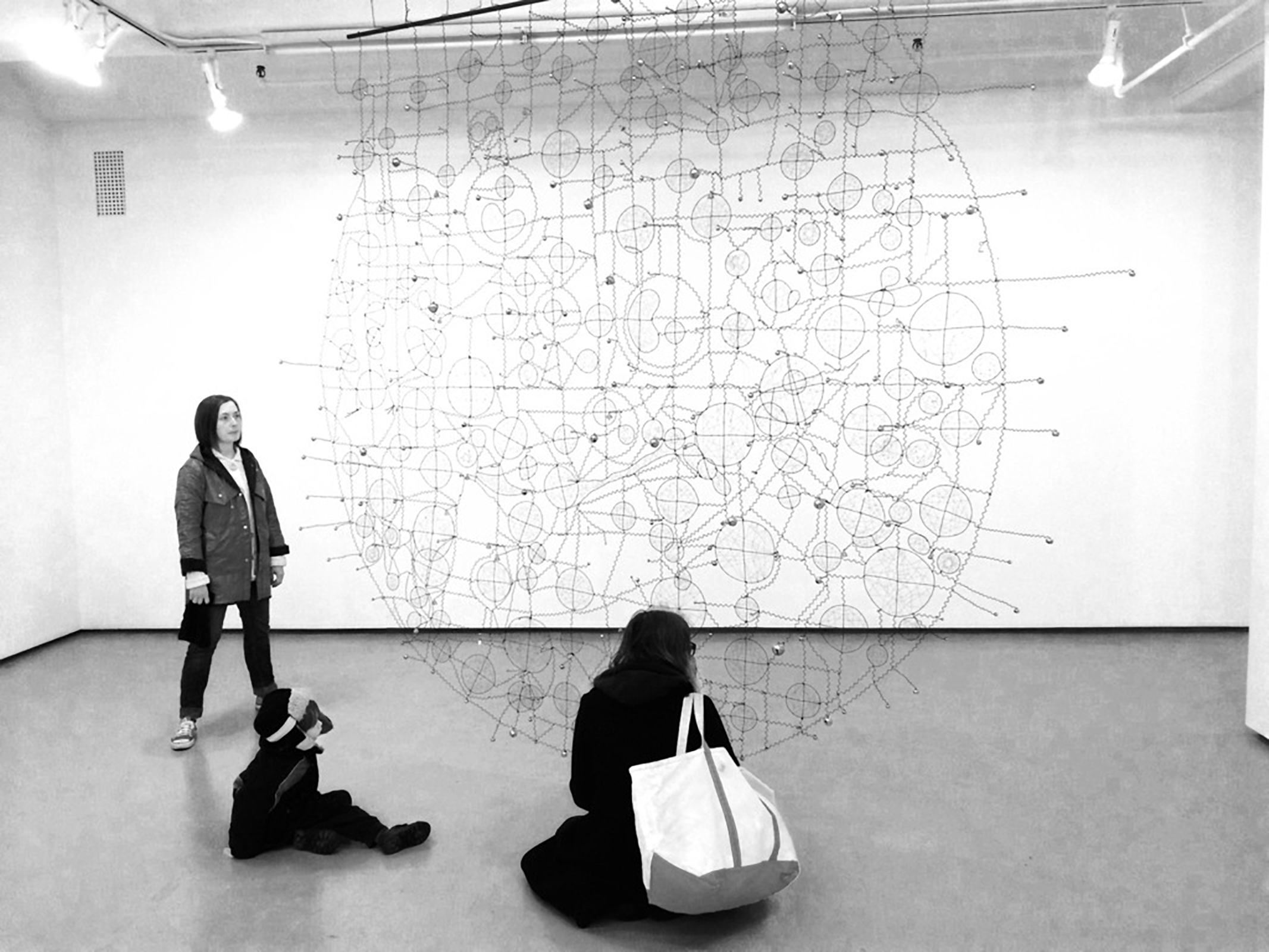

Bowery Nation, Installation View, The Aldrich Contemporary Art Museum, 2012

Brad Kahlhamer walks the line between worlds. Or better yet is continually creating a path of his own—a “third place” where imagination and identity are joined at the hip in a patchwork of Native icons, punk vibes, pop reference, all dripping with the language of expressionist gesture. Born in Tucson, Arizona, Kahlhamer has been in New York working across mediums since the 1980s—first as a design director at Topps Chewing Gum and soon an artist in his own right navigating the energies of Lower East Side, a mythic territory since woven into his evolving visual narrative. Today we find Kahlhamer coming off high-profile exhibitions at Chelsea’s Jack Shainman Gallery and a residency at the Rauschenberg Foundation in Captiva Island, now immersed in the role of Brooklyn’s flaneur and on the verge of a trip to Alaska. Most recently, Kahlhamer contributed an essay to the catalog for Fritz Scholder’s Super Indian exhibition, opening at Denver Art Museum in October. I met Brad at his studio in Bushwick to discuss underground cartoonists, hardcore bands, the art world, Native culture, sketching, and the one dream-catcher to rule them all.

Interview by Brandon Johnson

You’re about to depart for Alaska?

Next week. I’m doing this thing called First Light Alaska Initiative. I’m one of six people who are going up to conduct workshops on two weekends. Then we are going to hold over in Anchorage. I hope to get some fishing in if it’s not too cold or iced up.

What are the workshops?

It’s a woman named Anna Hoover who’s taken it upon herself to create a workshop and eventually a brick-and-mortar space. She’s bringing up a number of people. One, a “gut-skin sewer,” which is the old way of making clothes out of seal intestines. There’s also a chef coming up, and a musician, all from upper Alaska and Canada. We are traveling together as a Native entourage.

How long are you there for?

Eleven days. That’s a pretty good amount of time. I’m going to bring sketchbooks, do a lot of thinking. Just take it all in since I’ve never been up there.

Now let’s return to the beginning. How did you get involved with art making?

I came to New York in the ‘80s and worked at Topps Chewing Gum for about nine years as a design director. I was working with a lot of underground cartoonists like Art Spiegelman, who created Maus which became a really big deal. Others included Mark Newgarden, Kaz and Steve Cerio—it was a full immersion in the downtown creative world of that time. But I was also making watercolors at lunchtime and scavenging for sculpture materials on the Brooklyn waterfront where Topps was located. I finally quit Topps in ’98 to go full on with my own art and it seemed like the next day I was asked to be in a show in Amsterdam.

You were making your own work during your time at Topps?

On and off—I was cobbling together pieces as much as I could. I was putting together these giant sculptures out of rubber tires, these kind of impossible, belligerent things—dark, bleak, and black that summed up the Lower East Side at the time. I was also playing in a band. I recall we played with the Cro-Mags and people were throwing beer cans at us. It was all part of the experience.

You were in a hardcore band?

Well, we were in a hardcore show at Danceteria. At the time we had a rehearsal studio on Ludlow next to Bad Brains’ space and our lead singer knew a couple people around that band. Anyways, Ludlow Street had a lot of that history. So that was exciting. In ‘96/97 I started showing with Bronwyn Keenan and her start-up gallery downtown. In ’99 I was introduced to Jeffrey Deitch who had this idea to dedicate part of his gallery to the expressionist painting that was going on at the time.

And you were part of this grouping?

Yes. I was seeing myself as a next generation New York painter. I had been painting brushy expressionistic oils, not a popular direction at the time. The canvasses were smallish, probably due to finances and limitations of studio space. But Jeffrey had this idea. He was seeing yet another resurgence of this type of painting and brought me into the fold. There were to be four of us—one of which was Cecily Brown (who later went on to Gagosian). I stayed with Jeffrey and did three shows. The first was in ’99, “Friendly Frontier,” which was just a great experience and made me realize a broader context of the New York art world. Jeffrey was really looking for artists who were able to conjure up and present an entire universe and there were a number of us who were doing that at the time.

First Blast, 67″ x 64″, oil on canvas, 1999

Is creating your own universe something you sought to do as an artist?

No. I’m fairly natural in my production. I try not to over-think things. The idea of mating Western, Native American mythology and history with downtown New York created a world necessary for me to exist—a world I call the Third Place. The First Place being the life I would have lived had I not been adopted and the Second Place being the life I actually do live. The Third Place was the intersection of all my passions, the artwork, and the reality I created and was living. Jeffrey recognized that a number of people had similar visions at that time and picked up on that. Really exciting time to be showing. First of all to be living and working in downtown post-’80s and second to be part of the Deitch experience. I don’t know if that sort of thing can even happen anymore—the amount of experimentation was pretty remarkable on the scale that he offered.

Do you feel that post-Deitch you’ve had to seek a new direction?

It was such a moment unto its own. When that all ended there was a regrouping that had to happen. The outside world was also changing in New York with the economic collapse. It wasn’t just me, it was everyone. Everyone was scrambling, It was a time of changing and shifting. Yeah, it seems like 2008 was the year referred to over and over.

What was your situation in 2008?

I had always been hardwired to make art since I was a kid. You can retrench but it’s not like I’m not going to be an artist. I learned a lot during that period and became more self-sufficient. It’s all worked out. Jack Shainman approached me and we’ve taken it to the next level—in Chelsea now as opposed to downtown.

When I was in your studio last to put together the zingmagazine project, you showed me images from Bowery Nation, which I think eventually ended up being shown at Shainman?

Jack showed that piece in October 2013 just after I joined the gallery. It had already been acquired by Francesca Von Habsberg and TBA21. Jack borrowed it for the show, “A Fist Full Of Feathers.” Super generous of him to bring it to 24th street where the New York Times and a number of others reviewed it.

I remember you had it shown at the Aldridge Museum prior?

Yes, I completed Bowery Nation in 2012, capping it at a hundred figures and twenty-two birds. Richard Klein brought it to the Aldridge Museum and then it immediately went on to the Nelson-Atkins and their beautiful building, and soon after to Jack Shainman’s 24th Street space in New York, and finally ending up in Guadalajara at the MAZ (Museo de Arte de Zapopan) where it’s currently awaiting transportation to Bogota. Bowery Nation is going to be on the road for a while, which is thrilling. Guadalajara in so many ways reminds me of the Southside of Tucson, which is where I grew up. So it was cool to see those figures in an environment similar to where I came from. Growing up in Tucson, I was aware of the Heard Museum in Phoenix, Arizona. Around 1975 or so, I was visiting the Heard and for some reason the Barry Goldwater collection of kachina dolls made a huge impact on me in sheer number and quality. That’s a whole cosmology unto itself. Later, in the mid-90’s, I saw a Pow Wow Parade at Crow Nation in Montana, and subsequently created this conceptual Pow Wow float, which is why Bowery Nation looks like it does. I basically assembled my studio furniture and built an improvised platform. My idea was that anyone could do this and take part in the parade. These were the intercessors and ambassadors of this creative universe. It had a noise level that I really liked.

Was there any specific inspiration for the individual figures?

Again, going back to the Topps Chewing Gum experience, there was the anthropomorphic nature and characterization within the comic worlds. Combining that with things I had seen in the Heard Museum—the overall human idea that the doll or figure is translating myth and history to a younger generation is a universal concept. It seems to be a natural from time immemorial. The next level of figures I showed at Jack’s gallery in “Fort Gotham Girls + Boys Club” are more involved in articulation with their own dream-catchers. Recently, I was at this incredible residency in Captiva Island, Florida at the Robert Rauschenberg Foundation. There was a kiln and so I started picking up clay and building forms. That seems to be a huge new direction in translating my painterly impulses into my need to build objects.

How do you feel your work relates to Native culture? You are clearly interested and purposefully seek it out. But there also seems to be a rift.

That’s an excellent question. I’m currently in this show called “Plains Indians: Artists of the Earth and Sky” at the Met. It’s hugely important—spanning two thousand years of Native cultural history to evolving contemporary Native work. I feel great about being in it, but it’s also making clearer my position in relation to Native culture—this kind of inside, outside thing. I’ve created this bubble for myself and the show is bringing that more into focus. It was a very direct and conscious decision that I occupy a unique position in relation to both the Native and the contemporary art worlds.

And it makes sense because Native culture has been so interrupted historically. You’re not trying to preserve traditional culture but instead representing this position you’ve sort of found yourself in.

In my talk at the Met, I refer to it as a “collision of cultures.” When you see the show it is fairly clear from the late 1800s on. My work is more like you’re driving along and come upon the immediacy or suddenness of a car wreck that hasn’t quite been cleared off the highway. That’s not the most typical narrative.

That segues nicely into your zing project in issue #23, “Community Board”—a montage of images from photos to drawings, found pieces, and video stills.

Yeah, it’s beautifully designed. I love the way it turned out. There’s an incongruity or uneasiness from image to image, much like how the Plains ledger drawings work. Spatially, in the ledger drawings, multiple events occur within one page. When you think about it, some of them are more progressive than comics today. Ledger drawings were America’s first graphic novels.

What are you working on now?

The sketchbooks started last summer, reconnecting to a tradition I’ve always followed. It was this idea of drawing the new orbits of creative activity around Bushwick and Williamsburg. It’s based on the older tradition of the flaneur—the Parisian artist roaming the streets and recording. I think it’s just extending the studio practice out and beyond. Having a glass of wine with dinner at night and sketching. Keeping it going. It’s really that simple. That’s the beauty and brilliance of the sketchbook.

Does this feed into other work, like your paintings?

Well, traditionally, that would have been the case but now I’m posting them on Instagram (@bradkahlhamer ), which led to a show at the Wythe Hotel of selected spreads in three of the penthouse rooms. Suddenly the sketchbooks have their own life. I like the public/private nature of this exhibition because it goes back to the intimacy of the sketchbook as well. It’s the grand tradition of observational drawing. I’ve always drawn the figure. The reason I sketch is to drive up the intensity of the experience and make it more known to me. It’s natural for me to not make one but 248 drawings of, let’s say, skulls for my Skull Project (2004). It comes out of music because I play by ear and it was always the idea of repetition of learning that was ground into me as a teenager.

SuperCatcher, 11.5′ x 11.5′ x 12″, wire and bells, 2014

Tell me about your latest work, SuperCatcher.

The idea was to take every dream-catcher in the United States, whether it’s on a pickup truck or in a single-wide trailer, somebody’s bicycle or baby crib, and weave them all together in a cosmos, a universe of industrial wire. The spiritual rebar for an enriched dream reactor. I’m very pleased this particular work will be hung at the 2016 grand re-opening of SFMOMA.

Find more about Brad Kahlhamer on his website www.bradkahlhamer.net. View his new music video “Bowery Nation” here and follow him on Instagram: @bradkahlhamer .