Borjana Ventzislavova, Meet me in the red room (behind the curtain), 2018, wallpaper print

Borjana Ventzislavova, Meet me in the red room (behind the curtain), 2018, wallpaper print

Water Walk With Us, by Borjana Ventzislavova, curated by Gregory Volk, is on view at Radiator Gallery, 10-61 Jackson Ave, Long Island City, Queens, New York, through July 8, 2022. Friday 3-6pm and Sunday 1-6pm.

Interview by Gregory Volk

Borjana, your exhibition includes references to early 1990s post-communist Bulgaria, the Canadian Rockies and…Twin Peaks. Twin Peaks???

Well, yes, exactly—the reality in my hometown Sofia, where I was living in the early 1990s, was not far away from Twin Peaks’ reality. It was just after the fall of the Iron Curtain when on Bulgarian National TV during prime time, and after the news, Mark Frost and David Lynch’s series Twin Peaks was broadcast. So you sit down with your family in front of the TV and watch these wonderful, really strange scenes, something you never saw before, something that for many was also a kind of first encounter with the West. And we all hoped back then that the West was going to be the best. And then I would go out on the streets with my friends and play a Twin Peaks-inspired game. We would take our shoes off and cross the street to the taxi stand, and say to the driver, “The owls are not what they seem”… and he probably would have known what we were talking about. Because back then we didn‘t yet have private TV stations. We had only Channel 1 and Channel 2, and that was it. So the whole nation was watching Twin Peaks, imagine that. And me personally—a teenager at the time, going through changes, growing up into some kind of adulthood—it seemed to me that the whole society and the world around me felt not much different than a confused teenager, in the throes of puberty, who finally would find what it was looking for throughout its childhood—a bright, democratic future. And then you enter the world of Twin Peaks.

Who killed Laura Palmer? But also, who killed whom on the streets of Sofia? The newly-formed mafia back then were killing each other, including political figures. on almost a daily basis. So even far away, somewhere in America, in the small town of Twin Peaks, mysteries were more easily revealed than was the case with what was going on in my own city and country.

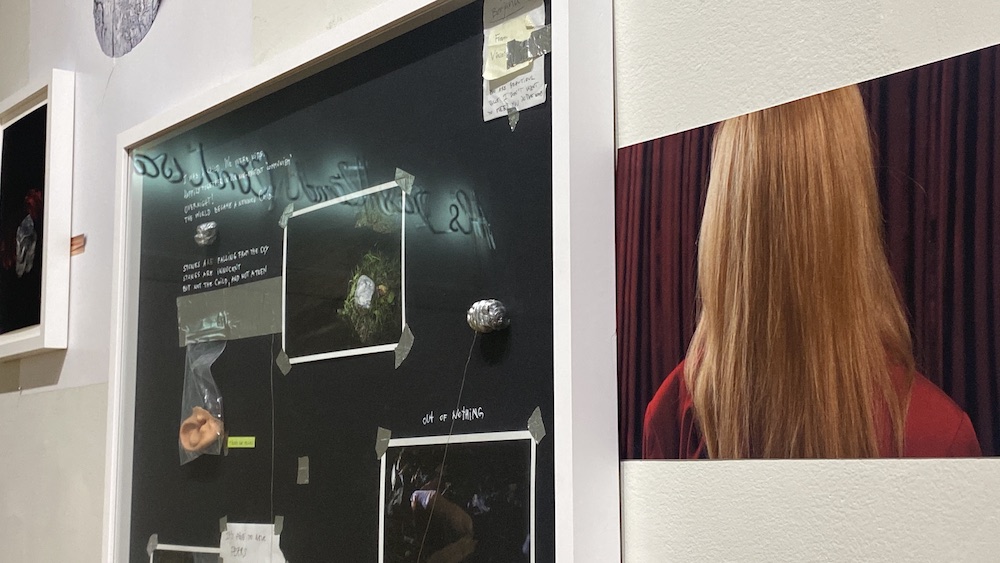

Borjana Ventzislavova, Wonderful and really strange #2, 2018 (from the installation Ten Peaks or Water Walk with Us), mixed media, framed

Strangely enough, I got a flashback of that time while I was doing a residency at the Banff Centre for the Arts and Creativity in the Rocky Mountains a few years ago. Provoked by nature and the atmosphere of the small town of Banff, which made me feel as if I were in Twin Peaks (filmed not far from there, in Washington State), I teleported myself back into the ‘90s to understand better what exactly happened in this essential moment of change and transition. There were questions that always bothered me but for which I never took the opportunity to find answers and connect the dots. What were post-communist societies—Bulgaria in particular—going through, what exactly did the Iron Curtain mean and for whom, what direction were we following, where were we going and why? And did we arrive somewhere? If so, where? At the same time, I had to rethink how all this related to a teenager who was also just discovering the music, books, and films that played a really important role for me not only then, but for my whole life. And all of this merged through the prism of close friendships.

So you see, all this was very complex, and very personal too, but also revealed some crucial aspects of the narrative of collective history.

You are an urban woman, having grown up in Sofia, Bulgaria, and you’ve lived for many years in Vienna, yet nature is crucial in your exhibition, including your video Wahkohtowin. Can you address this? What happened in Banff?

To be honest, I don’t know exactly what happened. My explanation is that the power of nature and the attempt to overcome a state of anxiety was what conquered me. I think there were a few moments which somehow intersected, but the major aspect throughout the whole process of creating this body of work was that I decided from the very beginning to follow only my intuition. My work is usually based on both theoretical and empirical research. Here, my approach was different from the very beginning. I didn’t want to necessarily produce new works while in Banff. But I had this very personal story where someone very important to me was very sick and was going through treatment back in my second hometown of Vienna. I felt very bad that I was not around and had to leave for my residencies (Athens, and then Banff). Upon arriving in Banff, I recalled this work that we had made together a long time ago: “Wishes for Fishes” (2002), in which a woman in a red dress navigates the city in a very clumsy way (frame by frame), accompanied by underwater sounds, and then this feeling of being breathless and in a vacuum is broken by scenes where she is jumping rope and singing. I don’t know why this particular work came back to me, but I was sure I should do something with the jump rope scene and I decided to present it more as a collective ritual, so I invited a few people to perform that and jump rope outside in nature, dressed in red. While I was looking for red clothes in the theater department of the Banff Centre I discovered this very beautiful traditional dress, which I didn’t know what and where exactly it was coming from, as it was also for me the first time I got closer to indigenous history and traditions, but somehow it reminded me a lot of a Bulgarian traditional costume. So I went back to my studio and looked it up, and I found that this dress was of course an indigenous regalia called “jingle dress.” The whole history behind it (and there were a few different versions of the story told by different First Nation and Native American communities) was that jingle dresses, also known as prayer dresses, are believed to heal the sick, and the dance is perceived as a healing dance. In the context of how, why, and for whom I started this project, this aspect made complete sense, and the work became absolutely important to realize. So I invited five colleagues/residents at the Banff Centre at the time—artists, performers and musicians—to take part in the video by jumping rope until they were completely exhausted. All performers were dressed in red. I was able to get in touch with people from the indigenous community outside the national park and to collaborate with Shaunna, an indigenous dress dancer who at the end of the video is dancing the jingle dress dance in her own regalia and performing the dance for the person who was going through this painful treatment and illness at the time.

Borjana Ventzislavova, WAHKOHTOWIN, 2018, HD Video, 13 minutes, color

Borjana Ventzislavova, WAHKOHTOWIN, 2018, HD Video, 13 minutes, color

For many years in my work, water has played an essential role. All locations where this video was shot are next to or above water sources (e.g., the Banff reservoir, which is underground, so sometimes water is not visually present). This was the criterion for selecting the landscapes for the video. Water has many meanings and symbolizes many different aspects of human existence and life on earth in all different cultures and communities, and for me it is an element I ended up using unconsciously at the beginning of my art praxis, until at some point I realised that in every other work I play somehow with the element of water, whether visually, acoustically, or as a philosophical metaphor. The title of my video Wahkohtowin is borrowed from Cree language and Cree law, and it literally means “kinship” or the interconnected nature of relationships and natural systems. This is a concept I then discovered to be part of many other works of mine, but that’s a different subject. So yes, the water somehow here too has this connective role, an element that unites us, that connects us, that is us.

But going back to your question, since I had to deal with wild nature (and—you’re right, I am an urban person), in order to cross the woods every day to get to my studio I had to look around to avoid confrontations with a grizzly bear, an elk or at least a Bambi family. So I had to go through a lot of anxiety, but this also helped me somehow to overcome my fear of danger. After I had a really strange and scary confrontation with an elk, then a few wonderful ones with deer, I started developing a very interesting approach to nature, maybe a very naive one, it’s worked for me since then. We are part of nature, and if we respect its rules it works for its members. So I stick to this rule and try to be respectful of my surroundings, to feel them and to act in the most adequate way possible. And here again, I never realized before that the mythology of art and culture can play such an important role for or against self-identification, recognition, and appreciation.

Objects, including red curtains and silver stones, have pronounced power in your work, but also seem like enigmatic evidence collected at a crime scene.

Silver, red—yes! As I mentioned earlier, there was no plan to follow. And that was on purpose. So I wasn‘t looking for anything.

But, of course, there is so much going on inside you, and then you have some kind of sixth sense and start to follow signs, like Agent Dale Cooper in Twin Peaks, who collects evidence to reveal who killed Laura Palmer. In my case, objects are just appearing without my even knowing their exact stories, but something tells me: here I am.

I used to work a lot with the color silver in the years before this project. Sometimes this would relate to the Iron Curtain and the illusions and fantasies we had of what was hiding behind it, or sometimes I would color objects of the past in silver, and another time my intervention involved wrapping the whole facade of my gallery in Vienna at the time with mirrored silver foil, a work called “Hey you, it‘s us!“ and so on…so I had many works that used silver. And then you walk in the woods of Banff Centre to get to your studio and something is shining in the high green grass…a big silver stone. Is the color natural, did someone paint it over? It doesn’t matter, it’s a silver stone.

Then again in the theatre department, while I was looking for red clothes, I found two rolls of red velvet fabric wrapped in plastic, almost like a dead body lying on the floor. And you remember in your childhood you used to see this red velvet frequently, the color of the Communist Party, the color of your red pioneer scarf, the color of all curtains, whether in movie theaters, cultural centres, or just the Lynchian curtains from the red room. The red room, known also as the “waiting room,” this anomalous extradimensional space, which connected to a grove in Twin Peaks’ Ghostwood National Forest, was believed by many to be the Black Lodge of local Native American legend. Anyhow, many spirits and spectres appeared to “live” in the red room…or behind the red curtains. And so, after the appearance of the silver stone and the red curtains you see the blond lady sitting there in the corner, with two pins pinned to her head. You are shocked. Straight away, you think: is she dead or alive? Then you think of Laura Palmer or remember your best friend from home who has the same hair color. You take two more steps and you discover it is just a blonde wig on a model head. Then you go over the props in the theater department and you find Agent Cooper’s original tape recorder, an amputated ear from Blue Velvet, or a severed finger of a lady who got robbed in an elevator back in Sofia; the robbers couldn’t remove the golden ring from her swollen finger, so they had to cut it off.

Borjana Ventzislavova, Who killed my butterfly, 2018, inkjet print on photo rag, framed, 120 x 80 cm

The next morning, when going down to the basement to do your laundry, you pass by a sign that reads “black lodge,” then another day you walk to town and you find a small shop in Banff which sells the two-heart “best friends” necklace. And while you are having this interview, ten meters away from you a lady with a costume in a zigzag pattern, the same pattern of the red room floor, is lying on the lawn…And so on and so on. In my Evidence series, I photographed a selection of all these objects, which seemed important to me during the process of following my intuition, again mostly in silver. I tried to create an index of all signs—as evidence of my reality-fiction scenarios, which are based on Twin Peaks and real stories and people.

Borjana Ventzislavova, Evidence #4, 2018, inkjet print on cotton paper, framed, 20 x 30 cm

Throughout the exhibition all sorts of correspondences and connections develop between different works, at times in different mediums, including visual and material correspondences.

Wahkohtowin. Yes, I truly believe things are related. And my works participate in these narratives of relations. Nothing is accidental, and this is always what my intuition tells me. Most of the time, my goal is to dive deeper into these relations, to reveal and understand them, and maybe sometimes to discover different perspectives on how things may relate beneath the surface.

While you address important cultural matters, your exhibition is also seeded with personal memories and experiences, for instance the neon “Als das Kind Kind war,” as well as with other references, including Leonard Cohen and Boris Buden’s writings on post-communism.

Absolutely! I used to forget a lot, especially names and titles, but if I remember something—fragments of texts, lyrics, quotes, whatever—then I know it has something very important to remind me of. I read Boris Buden’s The Zone of Transition maybe 7-8 years ago, and this one aspect of the child-parent relationship during the transition period of the so called post-communist countries and the Western world stuck in my mind. This moment of merging of these two worlds on both sides of the Iron Curtain back then, which still don’t always appear to be a genuine union, has somehow so much to do with the behavior of the parent telling the child how and what to do in order to become an adult, and the child who’s trying to fulfil the parent’s expectations without asking if this is the right way to go. The division of the world in two blocs felt like past history for a long time, but unfortunately with the war in Ukraine we see how absurdly and quickly things can regress. We don’t want to go back in time, but you see “Als das Kind Kind war” (which is a verse from Peter Handke‘s poem “Song of the Child” in Wim Wenders’s movie Wings of Desire) is a work dating from much earlier and which then found its exact place in this installation because of Buden’s text and thoughts on political and social transformation. And not only because of personal memories from watching the movie in the late 1980s and repeating incessantly “When the child was a child, it didn’t know it was a child…” but perhaps also because the child is sometimes more excited and doesn’t lose so easily the sense that everything is related.

And yes, such crossovers from assembled cultural references, personal memories, stories, and histories, play a most important role in creating these works for the show, and then again, here they come together in a flow to keep some balance and hint at my spell: “Water walk with us,” not Fire.

Your exhibition is animated by all sorts of ideas, yet it is also multisensory and acutely visual. To me, it feels very immersive and also like a voyage.

Thank you, this is what I try to do with my works, to travel with them while creating them and to travel means for me learning, experiencing, and enjoying, and when they are done to let the viewer to go on that voyage.

Borjana Ventzislavova, Ten Peaks or Water Walk with Us (installation view Radiator Gallery, detail 2022)