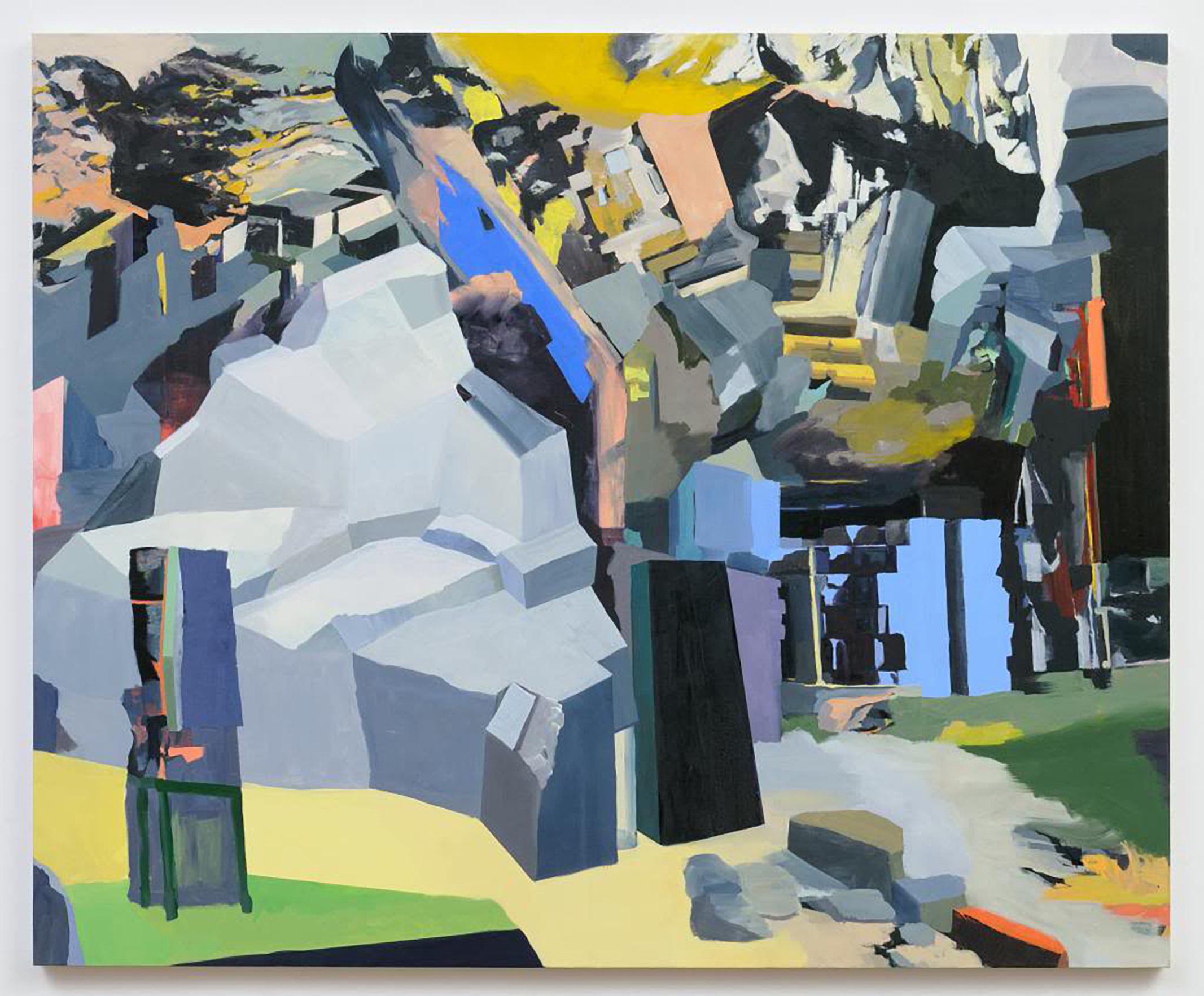

Stone-Tape Theory, Oil on linen, 2012

Billy Jacobs is an astute fellow, with razor-sharp opinions on music (and many other things). A Velvet Underground devotee, Bowie freak, rock ’n’ roll junkie. Billy is also a painter whose work I’d buy if I had the money. His paintings are the essence of desire—attractive yet elusive. I visited Billy at his studio on Wooster Street in Soho to attempt to speak about painting after staring at a computer screen all day. Here are the results.

Interview by Brandon Johnson

Last visit you had paintings on the wall of governmental conspiracy figures, Manson girls, and Area 51. What initiated these interests?

I have always been a sucker for esoteric and sensationalistic topics of 20th century history. My interest in these topics developed by hearing passing references in films or music when I was younger, and I would need to seek out the story. I always had a hard time accepting that these people or events were real, and so I would become transfixed by their images, which act as a kind of documentation or evidence of their existence. Why did I then feel the need to paint them? I am not sure if I can answer that beyond saying it was a compulsion and felt very logical. Maybe I wanted others to become as fascinated with these topics as I was?

What’s your favorite conspiracy?

I’ll go with a classic: the JFK assassination. I began “researching” it when I was about twelve, and was intrigued by the cognitive dissonance surrounding the event. The majority of people do not believe the official story, yet they still have a hard time accepting a conspiracy theory. Recognizing that dissonance at that age definitely warped my view of the authoritative voice of history. My mistrust was exacerbated by the availability of so much evidence and documentation, especially photographic. This still is pretty unique to the JFK assassination: you can actually see photographs of the alleged participants, and learn about their biographies, and theorize motives. It stands in stark contrast to many other conspiracies where the participants are just faceless government organizations and the motives are vague “national security” It was probably my introduction to abstraction as well. I would pour over the high contrast black and white photos, in which researchers would claim that a fuzzy white mass definitively proved that there was a second gunman or whatever. A conspiracy I love in terms bizarreness, is anything to do with Reptilians. I do not claim to be an expert on this conspiracy, but the gist is that there are Reptile-like humanoids that inhabit our leaders. There are two schools of thought on the Reptilian motives: one that they are in collusion with the classic Gray Aliens, and trying to enslave humans, or that the Reptilians are in conflict with Gray Aliens, who are benevolent creatures watching over us. I am so intrigued that for some people these theories are the logical way to understand the world.

Lately, you’ve been engaged with the idea of landscape, but unlike your “bird’s eye view” paintings, these are divorced from subject. What happened?

Most of the aerial paintings were of Area 51, a secret military base in Nevada. By making multiple paintings of the same subject, the process became more about exploring abstraction than just rendering a specific image. I realized that I wanted paintings that were more visually abstract, and had vaguer and more mysterious subject matter. I began painting Egyptian ruins because I know very little about their historical or cultural specifics, but have always found them visually fascinating. Ironically, about six months after I began the paintings, the revolution in Egypt occurred. It was an interesting reminder that you cannot ever escape the social/political implications of a subject matter.

After painting fairly realistic landscapes of the ruins, I became more focused on the structures themselves. I began collaging my source material, forming new structures. I was focusing on rendering these new, unreal structures, instead of just depicting a vista with a sense of space. This rebuilding simultaneously allowed for me to push the abstraction of the painting and disrupt conventions of the landscape genre, to an even greater degree than the aerial paintings.

I see Egyptian ruins as almost metaphorical to your the development of your painting. Could you be more specific about why Egyptian ruins fascinate you?

Ancient Egyptian ruins are a loaded, yet not pointed, subject matter. They embody ideas of the past, specifically bygone civilizations, mankind’s physical creations, etc., but they also imply the present because they exist today. In fact, a lot of my source material are images by Francis Frith, the 19th century photographer. Today, his black and white prints feel almost as distant as the ruins themselves. I am sure there is a colonization critique to make about Frith’s work, as he mined another culture for his work. I do not know or care about his intentions, though. I initially chose his photographs purely for visual reasons, but I like that using them inherently comments on the tendency for any era to assess past eras. However, I do not identify with Frith any more than I do with the Egyptians who made these structures. Rather, I find both cultures equally exotic because of the distance that time creates.

Something we didn’t discuss at your studio was titles – which, looking at your website, seem important. Are they important?

We probably did not discuss them because they are not really part of my process. I keep a list of potential titles and, when I am finishing up a body of work, I will impulsively assign titles to specific paintings. It is not completely free association, but it is usually a snap judgment. The phrases mostly come from songs, films, etc. and perhaps are paying homage to my artistic inspirations. I can understand why a lot of other artists leave their work untitled, but that always disappoints me. Since the viewer usually will read the title after seeing the work, it seems like such a great opportunity to create another level of tension by confirming or denying the tone, subject matter, or attitude of the work. However, I do choose series or exhibition titles with much more care, as they will often be an introduction to the work.

You brought up lying a lot in our discussion. What is it with painting and lying?

A good friend of mine has often described painting as “a lie,” so that is often on my mind. Even non-representational or conceptual painting usually has an optical or illusionistic space or aspect, which for me, is the quintessential trait of a painting. This illusion, or lie, or fantasy is the perfect complement to historical subjectivity. History is an agreed upon, somewhat inaccurate, and essentially fantasized narrative. That idea gets compounded with alternative histories: conspiracy theories, forgotten histories, myths, and other revisions. Our inability to accurately grasp events is perfectly manifested in a painting’s abstraction.

Can you explain the term “paintingland”?

The title of my first career retrospective?