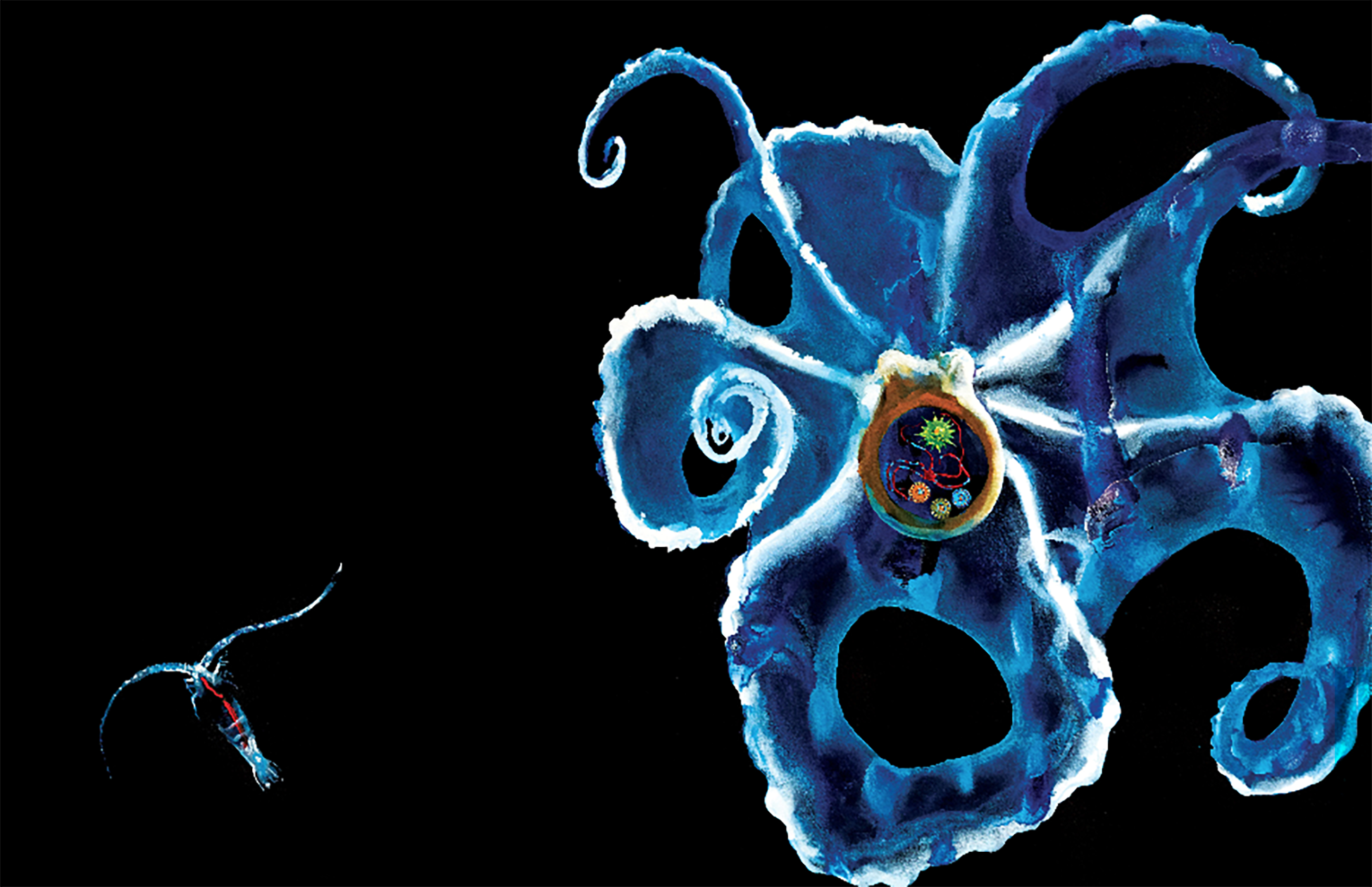

Pages from Alexis Rockman’s “Bioluminescence” project in zingmagazine issue 24, 2013, gouache on black paper, courtesy Baldwin Gallery, Aspen, CO

Technical skill and fantastic imagery make Alexis Rockman’s paintings immediately appealing to the appetites of the eye, but his nimble approach in applying scientific and historical anecdotes satisfies intellectual intrigue. The realms of the real and the surreal meet in a place where jellyfish and tabby cats live amongst sunken bridges and in abandoned buildings. These scenes, though imaginary, are informed by very real circumstances and quantitative evidence which tells us that our earth is changing in alarming yet preventable ways. Integrating with nature by traveling the globe, studying the species and environments he depicts, and sometimes using elements of the ecosystem to create his art are testaments to Rockman’s passions in conservation and environmental activism, but his work carries meaning that extends far beyond those ideals.

Rockman’s “Bioluminescence” project in zingmagazine 24, curated by the Drawing Center’s Brett Littman, depicts a dark, watery world where life generates its own light—a domain so opposite from the terrestrial sphere. These images are a continuation of his artistic contributions to the film Life of Pi, and is a series that he has expressed great joy in creating. A continuation of another series, Field Drawings, is currently on view at the Parrish Art Museum in Water Mill, New York through January 18, 2016.

Interview by Hayley Richardson

Your project in zingmagazine 24 features watercolor paintings of deep-sea bioluminescent creatures, as well as underwater entities of your own imagination. These images share a relationship with a previous project you did when you created concept artwork for director Ang Lee’s 2012 film Life of Pi. Can you summarize how the zing project developed from your experience working on the film?

The images in zing were done in the same language as Life of Pi, with the same materials, and about similar ideas. I had such a great experience working on Life of Pi, but the studio that made it, 20th Century Fox, owned that work. I felt it would be great to revisit that type of work several years later for a show at the Baldwin Gallery in Aspen in 2013.

The work I did for Life of Pi was constructing a narrative visually for a sequence called the Tiger Vision sequence which was when the tiger, Richard Parker, and Pi are in such dire straights both physically and psychologically and spiritually that they come together and voyage to the bottom of the ocean and it’s not clear who’s who. My role was to visualize that and create a cinematic experience. I ended up making about 50 drawings that I showed at the Drawing Center several years after I did the work in 2011. These drawings, in sequence, were used as reference by animators and that became a one minute and twenty-three second sequence. The project for zing was done two years later. There were four years between the time that I first met with Ang Lee in 2009 and when the movie was finished in fall of 2012. There was an earlier version that we worked on in development and preproduction for the movie that no one will ever see because the studio didn’t approve it—they thought it was too expensive. So the Tiger Vision sequence was kind of a condensed and stream lined version of what we wanted to do initially. Ironically, I think it turned out better than what we wanted to do the first time, but getting it to happen was a bit of rollercoaster ride. Ang is a master of the long ball. It turned out fantastic. It was wonderful to see the sequence be so close to the drawings—Buf, the company that did it, did a great job.

The paintings are gauche on black paper, and I read that you had never painted that way before.

I started out making drawings with black ink around the characters to sort of position them in the darkness of the deep sea with no sunlight whatsoever. Then I realized why not just do the damn things on black paper?

There is a style of drawing in India known as kolam, which is characterized by decorative, mandala-like designs, and I noticed that one of your Life of Pi underwater paintings exhibited at The Drawing Center has a white geometric pattern in it that looks very kolam-esque. This design also appears in the movie in the Tiger Vision sequence. I am curious if any visual traditions of India played a role in how you developed this project.

That’s exactly what it is and it was very intentional. That’s what Pi’s mother character does when she’s with Pi and she teaches the pattern and the meaning to him with sand. In our Tiger Vision sequence his mother ends up beheaded by a knife fish.

Did any other visual traditions of India play a role in how you developed this project?

The squid and the whale composites in the Tiger Vision sequence made out of other figures. There’s an Indian tradition of having an elephant made out of many other elephants or what have you. Like Acrimboldo, but Indian.

You grew up in Manhattan and your mother worked at the American Museum of Natural History, where you spent a lot of time during your youth and was great place of inspiration for your artwork. Were you able to spend much time in nature, outside from the museum and the city, as a child?

I went to camp, I went to the zoo. That’s not nature, but it gave me a sense of longing. I also went to Australia. I was very familiar with things out in the world looking at National Geographic or through watching Wild Kingdom on TV.

You have traveled the globe to become closer with the natural environments and wildlife you depict, and you recently spent time in Michigan studying the Great Lakes region for a show at the Grand Rapids Art Museum opening in 2018. Do you travel in preparation for all your major exhibitions, or only certain ones?

I’d say if I can it’s a good idea. I just spent the last couple of days traveling around New York City, throughout the five boroughs.

Was that in relation to your current exhibition, East End Field Drawings, at the Parrish Art Museum in Watermill?

No, it’s for a show I am doing at Salon 94 in April.

Can you talk more about the East End Field Drawings exhibit, like your process in creating the work and how it all came together?

The images are made out of material from the area directly and nothing else but acrylic polymer. They’re minimal, but also very maximal in terms of being pieces from the landscape or ecosystem. They’re made out of sand or soil or leaves. The image is actually made out of those materials. For instance there’s a place called Town Line Beach in East Hampton that had a beached Leatherback Turtle. It had been dead for a couple days and gulls were eating its head. It was an amazing scene. I collected sand from underneath it and made drawings from the sand of that turtle and some other marine life that are common to that particular beach. I’ve done this for the past twenty some-odd years in different places. Tasmania, the Amazon, Madagascar, the La Brea tar pits. They are all Field Drawings, but this is a separate body of work.

What are some places in the world you haven’t been to yet that you would like to visit, whether for research purposes or just for pleasure?

Borneo or New Guinea, or both, amongst many other places. Burundi, Tibet, The Congo, there are so many places I would love to go.

I watched a video of the lecture you gave at The Smithsonian American Art Museum in 2011 and in it you covered a great span of art historical references that have informed your work over the years. Did you begin to cultivate knowledge in this field early in your career?

I’ve always loved art history. Before I decided I wanted to be a painter—I really loved art history and copied many old master drawings when I first started.

Your Wikipedia page says that your work “has sometimes been associated with a new gothic art movement,” which is loosely defined as “a contemporary art movement that emphasizes darkness and horror.” Do you feel your work fits with this description, or is there another current movement or direction you resonate with?

(Laughs) Yes, I saw that and don’t know what that is! I didn’t do that page. I am not against it. I’m like, “alright, whatever you say.” I like Gothic and I like horror, so why not? I’ve always gone my own way so to speak. There are many artists that I admire that might be considered that, but it’s not something we discussed.

You are known as an environmental activist, yet seem hesitant to consider your paintings as “activist artwork.” Can you explain why that is?

First of all it’s art. I think anything anyone does is political, that’s the position I come from. But to label something as activist artwork it really ghettoizes it pretty fast. I’m trying to juggle many things and there’s a rainbow of meaning.

What do you think is the best vehicle to spread the message of environmentalism to a mass audience?

Probably advertising. The skillful way they can sell alcohol to children is probably the best way to get people to care about conservation. If you can sell cigarettes to kids why can’t you get them to care about the environment? I would suggest putting an attractive person in it and there you have it.

Besides the exhibitions we discussed, do you want to talk about any other shows, events, or news that you have upcoming?

I have some things going on but I can’t really talk about it now. “A Natural History of New York City” at Salon 94 in April, 2016. It includes plants and animals from the history of New York City- from dinosaurs from the Cretaceous in Staten Island (145-66 million years ago) to the squirrel in our back yard in the west Village in Manhattan and in between.