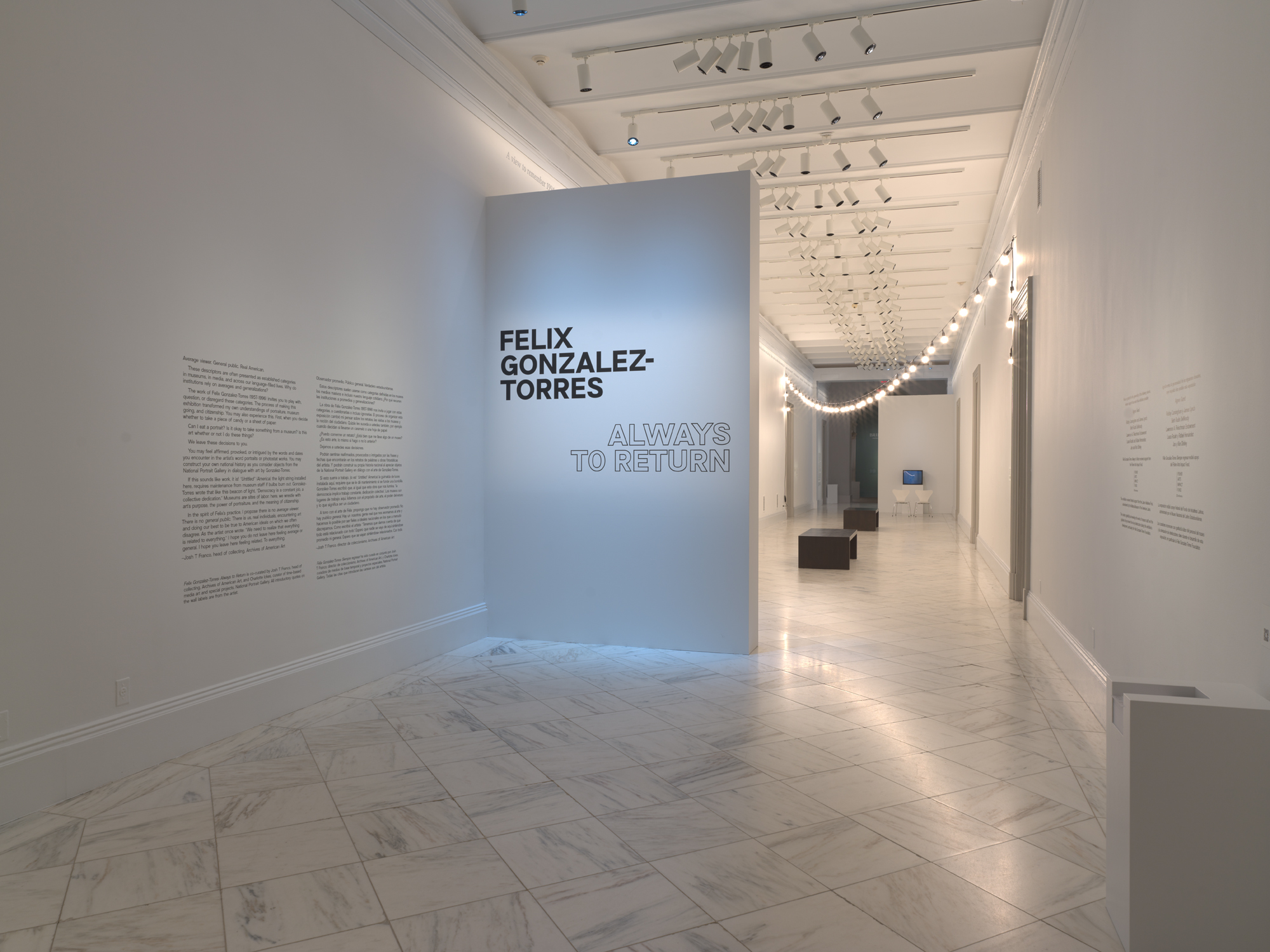

Installation view of “Felix Gonzalez-Torres: Always to Return”

Photo by Mark Gulezian/National Portrait Gallery

Art historian Charlotte Ickes is Curator of Time-Based Media Art and Special Projects at the National Portrait Gallery in Washington, D.C. Among her recent projects, she co-curated Isaac Julien: Lessons of the Hour—Frederick Douglass (2023–2026) and Viewfinder: Women’s Film and Video from the Smithsonian (2021). She also commissioned Birthright (2022), a performance by Maren Hassinger. Her latest exhibition, Felix Gonzalez-Torres: Always to Return, is co-curated with Josh T Franco, Collector at Large at the Archives of American Art.

Charlotte Ickes as Interviewed by Claire Dillon

I love it when people say: ‘But it is just paper. It is just two clocks next to each other. It is just light bulbs hanging.’ I love the idea of being an infiltrator. I always said that I wanted to be a spy. I want my artwork to look like something else, non-artistic yet beautifully simple.

– Felix Gonzalez-Torres in conversation with Tim Rollins, 1993

The exhibition Felix Gonzalez-Torres: Always to Return begins outdoors, beyond the walls of the National Portrait Gallery and Archives of American Art. Visitors first encounter strings of lights from “Untitled” (America) (1994) hanging from the venue’s façade, lining 8th Street NW, and shining through the windows of the Martin Luther King Jr. Memorial Library next door. When I saw the exhibition in December 2024, “Untitled” (America) was also intertwined with a second set of lights, which decorated the local holiday market. As they subtly swayed in the crisp air, the warm glow of the artwork’s frosted bulbs contrasted with the clear lights installed for the season’s festivities.

A label accompanying this installation can be found indoors and through QR codes pasted to the sidewalk. The text in the library explains the key components of the work, and continues with an interpretation:

When illuminated, “Untitled” (America) requires continued maintenance from library staff who must replace burned bulbs. ‘Democracy is a constant job, a collective dedication,’ Gonzalez-Torres wrote in a statement about “Untitled” (America). As a beacon hovering between promise and precarity, this work, like democracy, requires choice, maintenance, vigilance, and labor. During election season, the DCPL [District of Columbia Public Library] serves as a voting site. Without voting representatives in Congress, D.C. residents are only partially enfranchised. Exhibited in this context, what meanings about democracy does this work generate? As the artist said he hoped the work ‘will light some peoples’ spaces, at least for a short time.’ Hopefully, “Untitled” (America) ‘lights your space’ as you read, eat, and attend civic programs at the library, the museum across the street, and elsewhere.

This brief description of the installation raises several themes that permeate the work and this exhibition: by using everyday objects to create untitled artworks, most of Gonzalez-Torres’s pieces remain open to infinite interpretation. While his parenthetical titles suggest directions for contemplation, the responses of the audience and curators are just as important as the artist’s intentions. In this case, the title of the work and its installation by a museum of portraiture prompt consideration of the conventions of representation, not only of people, but also of concepts like America.

Site-specific interpretation is a recurrent theme in this exhibition of Gonzalez-Torres’s art, and it is particularly significant because this is the first major presentation of his work in the nation’s capital in three decades. Collaborating between the National Portrait Gallery and Archives of American Art, Ickes and Franco staged original juxtapositions between the institutions’ permanent collections and Gonzalez-Torres’s work. In doing so, they interrogate the themes of portraiture, institutions, politics, and constructions of public, private, identity, and history. For example, the artist’s photographs of the American Museum of Natural History’s memorial to Theodore Roosevelt—documenting only the engraved words Historian, Scientist, Statesman, and Ranchman rather than the infamous equestrian statue—are displayed next to Roosevelt’s painted portrait in the Gallery’s permanent exhibition, America’s Presidents. Gonzalez-Torres’s nonrepresentational approach challenges expectations of what a portrait can be, and this exhibition created unique opportunities to compare his work with traditional definitions of this genre.

The extension of Gonzalez-Torres’s work into other exhibitions within the museum and into the city recalls an oft-quoted 1995 interview with Robert Storr, in which the artist stated:

There’s a great quote by the director of the Christian Coalition, who said that he wanted to be a spy. ‘I want to be invisible,’ he said, ‘I do guerilla warfare, I paint my face and travel at night. You don’t know until election night.’ This is good! This is brilliant! Here the Left we should stop wearing the fucked-up T-shirts that say ‘Vegetarian Now.’ No, go to a meeting and infiltrate and then once you are inside, try to have an effect. I want to be a spy, too. I do want to be the one who resembles something else. We should have been thinking about that long ago. We have to restructure our strategies and realize that the red banner with the red raised fist didn’t work in the sixties and it’s not going to work now. I don’t want to be the enemy anymore. The enemy is too easy to dismiss and to attack. The thing that I want to do sometimes with some of these pieces about homosexual desire is to be more inclusive. Every time they see a clock or a stack of paper or a curtain, I want them to think twice.

Today, his piles of candy and stacks of paper stand quietly, but powerfully, among works in the permanent collection. In my mind, the presence of Gonzalez-Torres’s work amidst both a holiday market and an exhibition of presidential portraits is a perfect demonstration of this strategy. In another example, pictured below, the artist’s paper stack “Untitled” (Death by Gun) (1990)—a record of 464 victims of gun violence in the first week of May 1989—sits beneath Christian Schussele’s painting Men of Progress (1862), which depicts American inventors, including firearms manufacturer Samuel Colt. The men are represented in a fictive meeting in the very building in which this exhibition is now held: the former U.S. Patent Office. This pairing attests to the artist’s ability to intervene in such institutions, and the curators’ careful consideration of the site in which they work.

Felix Gonzalez-Torres, “‘Untitled’ (Death by Gun)”

© Estate Felix Gonzalez-Torres

Courtesy Felix Gonzalez-Torres Foundation, Photo by Mark Gulezian/National Portrait Gallery

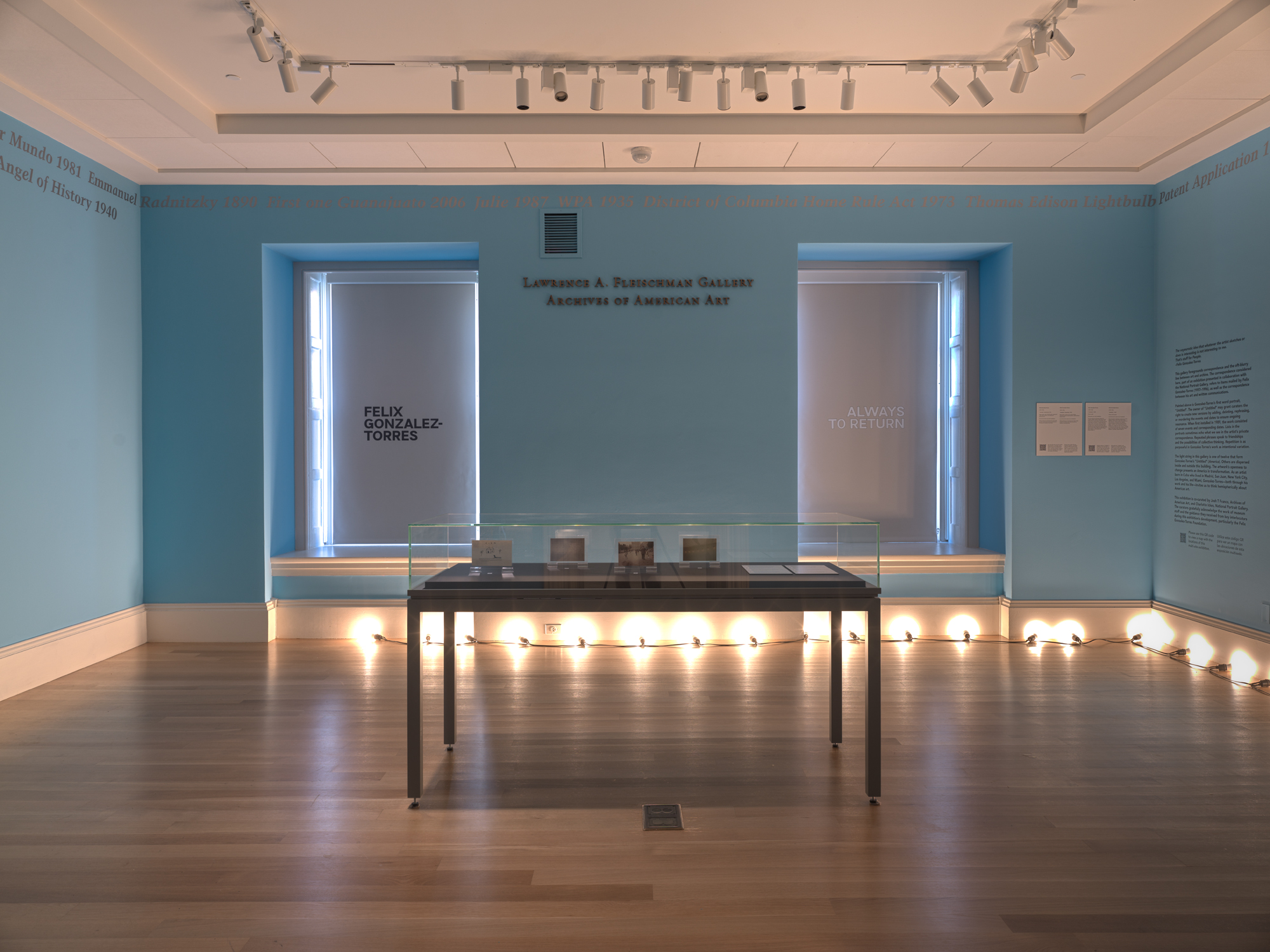

Gonzalez-Torres’s art also reaches into the present, which is most evident in his exhibited word portraits. These portraits, composed of formative events listed in silver paint around the perimeter of a room, were made with the input of their initial owners to create a timeline of personal and public moments that represented them. New versions of a portrait can be created with the owner’s permission, and in this exhibition, events such as “CDC 1981” are joined with “PrEP 2012” and “CDC 2020,” which occurred after the artist’s untimely death from AIDS-related complications on January 9, 1996. Other posthumous events include “January 6 2021” and “Equestrian Statue of Theodore Roosevelt 2022.” In this way, Gonzalez-Torres’s work, and particularly his conceptual portraits, represent not only specific people, times, or places, but also the broader contexts that surround their beholders and the institutions in which they are exhibited.

Felix Gonzalez-Torres, ” ‘Untitled’ (Portrait of Dad)”

© Estate Felix Gonzalez-Torres

Courtesy Felix Gonzalez-Torres Foundation, Photo by Mark Gulezian/National Portrait Gallery

When I visited Felix Gonzalez-Torres: Always to Return, I was struck by the juxtaposition between the interpretive openness of Gonzalez-Torres’s work and the specificity of the National Portrait Gallery’s mission to “tell the story of America” through portrayals of the nation’s people. How did you formulate the ideas behind the exhibition?

I saw Felix’s word portraits at Andrea Rosen Gallery in 2016, in an exhibition curated by Julie Ault and Roni Horn. They blew me away with their complexity, as they told history differently through portraiture, and I wondered how that process could be modeled in an exhibition.

Felix’s work is exhibited all around the world, so I knew that place and context would be critical in order to bring something additional to the work. We got very specific about site: our site as a collection, our site at the Smithsonian, and our site in Washington, D.C. This involved placing art from the collection in conversation with Felix’s work, and then moving the exhibition out into our city.

When I started at the Portrait Gallery and learned that the Archives of American Art was home to the Andrea Rosen Gallery records, I approached Josh Franco about a potential collaboration between us and our two units, as we call them in the Smithsonian. I like collaborating, and more than that, I was trying to create a discursive conversational format that would make the sum greater than its parts.

Collaboration pervaded my experience curating the show and writing new versions of his word portraits. This approach complemented the doubling, twoness, and coupling that are present throughout Felix’s work. With the Archives’ footprint in the museum building, we had the opportunity to move beyond one single space, which highlighted the multifaceted nature of his portrait practice. Between his artwork and his correspondence, we see the logic of lists, the major and the minor, and other themes echoed across different materials. The Archives offered a great space to do that work.

I was originally thinking about a survey of his portrait works, but we moved away from that format through conversation and deeper thinking. That’s something I’ve learned from Felix: his work is about being open and humble enough to know that you might start with one idea, but you also have to learn and let your thinking change. This is now how I want to approach everything I do.

There are moments when the exhibition refers to the history of the institution, and I noticed that, in some ways, the galleries form a portrait of the National Portrait Gallery itself. Did you and Josh see your work in this light? In what other ways did the venue inform the exhibition?

As a curator, I think one of my responsibilities is to create a conversation between the context in which the work was made and the context in which it is exhibited now. Greg Allen articulated this so beautifully in a recent blog post about the show. It just so happens that, within this exhibition, some of that conversation includes the history of the building and the institution.

I hadn’t originally thought of the exhibition as a portrait of the institution until I was asked. I think that it could be. Felix made word portraits of institutions, which prompt a key question: who gets to represent the institution? A really beautiful takeaway from the institutional portraits—like “Untitled” (Portrait of MOCA), which we have on view—is that an institution is ultimately made of people. It’s a portrait of MOCA, but there always has to be a person to make the versions of the word portrait, or interact with lenders, and so on. That tension is really interesting to me. An institution is a mission statement, it’s a building, it’s a set of systems, but it’s also made of people, and it’s not static. That informed our decision to write and sign two different introductory statements to the exhibition. We wanted to destabilize the idea of an authoritative institutional voice. While the exhibition relates to the institution, it’s also a model of how we tell history, which I see Felix working through in these portraits.

I did fear that that displaying figural works from the Portrait Gallery collection alongside Felix’s pieces, speaking directly to some of his parenthetical titles, could close down the potential meanings of his work. I hope that this approach presented the art in unexpected and meaningful ways. In doing so, I could see his work with fresh eyes. Through that process of thinking about these connections, I strove to model the kind of history-writing that he proposes with his art.

What was the process of contributing to the word portraits? Did you think of these interventions as expanding a portrait of the subject, or of creating a portrait of you and Josh, or as something else?

When you borrow a word portrait, you don’t automatically have permission to create new versions, but we were granted that right with all three of the word portraits in the exhibition. The process for each portrait was different, and frankly, I didn’t know what to expect going into it.

Robert Vifian, the subject of one of the exhibited portraits, is amazing. I’m so thankful that Felix’s work allowed me to be introduced to him. Robert collected other works by Felix and commissioned this word portrait; he is a really visionary collector. He happens to be both the owner and the subject of this piece, and it was great to co-write this version with him.

This is the first time that his portrait has been shown in the U.S., and we took a pretty light touch with it. He told us which version he wanted to use, and most of what we added spoke to the context of the room in the exhibition. Then, as a result of our conversations, Robert added a few new events and dates. Josh had the opportunity to go out to Paris and saw a version of the word portrait installed in Robert’s home, ate at his restaurant, and went to visit the Gertrude Stein & Alice B. Toklas grave, which was the subject of two of Felix’s other works in the exhibition. It was Josh’s first time in Paris, and it was all kind of framed by Felix.

Bringing “Untitled” (Portrait of MOCA) to the East Coast, to a very different kind of institution, came with a very different kind of site specificity. When displayed in the Smithsonian, “MOCA” is not necessarily recognizable, as it’s not even spelled out in the title. It required a real balance between being a portrait of MOCA or the Portrait Gallery, and our thoughts of MOCA and L.A.

I would say that “Untitled” was the hardest one. I still think about it—and have my regrets! This was Felix’s first word portrait. When it was first shown at the Brooklyn Museum for VisualAIDS’s inaugural Day Without Art in 1989, it only consisted of seven events and dates. But now there are more than forty versions. It also grew during his lifetime. We wrote two versions of “Untitled” for the exhibition. One version is installed in the main corridor of the exhibition, and a different, shorter version is in the Archives of American Art gallery in the same building.

We couldn’t help but think about the fact that, at one point in time, Felix called it “Untitled” (Self-Portrait) for his show at the Hirshhorn in 1994. He ultimately landed on “Untitled.” It’s the only word portrait without a subject named in parentheses. That makes it hard: it’s totally expansive. At the same time, I couldn’t get out of my own head knowing that a lot of the work’s reception centered on the former title, “Untitled” (Self-Portrait). However, these interpretations are not mutually exclusive: biography is there, and so are other things. They inform each other.

The word portraits are supposed to include events and dates that were formative for the subject. But this one doesn’t name a subject: could the subject be us, our personal lives, our professional lives? Does that distinction even matter? It’s a really difficult process and a huge responsibility. There is a generosity to it, sure, but Felix makes you work hard, and in ways that you aren’t trained to work.

To begin drafting new versions of “Untitled” for the exhibition, we reserved the Archives of American Art conference room and covered long tables with butcher paper. We read aloud all of the past versions of the word portrait, wrote them down, and started moving things around and talking it out. You begin to notice patterns and repetitions across portraits. It’s an overwhelming amount of information. I asked an intern to research almost every single term. Of course, sometimes we just didn’t know what a term meant, and each one could have multiple possible meanings. We tinkered on our computers for months at a time, had another retreat, printed out the text to scale and arranged it around the rooms, and we only stopped when we had to get a quote from the sign painter. We also had to make decisions during the installation. For example, all three portraits call for metallic silver paint, but we had to decide what that meant. The Archives space is painted blue, so it was harder to read the paint color that we used upstairs on white walls. With our permission, Sean Danaher, the sign painter, added a little pewter to make it more legible.

Installation view of “Felix Gonzalez-Torres: Always to Return”

Photo by Mark Gulezian/National Portrait Gallery

I imagine all of these materials from the retreats are kept somewhere?

I think it’s all in Josh’s office. The paper has food stains on it from lunch and snacks; we were in that conference room all day. That’s the thing about this work—you can’t just put something on view and write a wall label.

The work really brings people together; I love picturing Josh in Paris with Robert.

The world Felix built was so amazing. Some of the people we’ve met… I treasure those conversations. In terms of this exhibition, I’m very cognizant that we curators come from a generation that is several generations removed from Felix’s life. Many of the great shows were done while he was alive, with people who knew him, or who had lived experience of his generation. I’m very aware of our distance, and I’m not saying that one is better than the other. It just is.

Did the nature of the art or of the exhibition create opportunities to work in new ways, either for you as a curator or for your colleagues? I’m struck by the amount of physical work involved: clearing debris from the candy piles, straightening up the paper stacks, and so on.

The caretaking is significant. Josh and I have done a lot of hands-on work, including during the installation. The maintenance of the show is a huge amount of effort—it’s way more than I expected and has been a real learning experience. We’ve done at least five roll calls with our security colleagues and are in continuous conversation. The work also entails care and tending in physical ways: replenishing piles and stacks, tidying things up. I’m always removing the scuff marks from “Untitled” (Death by Gun).

It’s so complex. This is only the tip of the iceberg, but I know that my experience with Felix’s work and keeping it on view will forever change the way that I approach my curatorial work. His art will always be with me in that way, long after the show closes.

Could you return to the title of the exhibition, and take us through how you chose it?

The title is from the video “Untitled” (A Portrait), which for me, is one of the most significant works in the exhibition. At one point, we thought of using “Angel of History” as the subtitle, from Walter Benjamin’s Theses on the Philosophy of History, which is important to our thinking, and Felix was a great reader of Benjamin. We have “Angel of History 1940” in the version of “Untitled” exhibited in the Archives space. We ended up choosing the title “Always to Return,” and the piece that it comes from still feels so resonant now, decades after it was made. It’s both of its time and of our time. The work says things like, “a new Supreme Court ruling,” or “a distant war.” It also includes “a shortness of breath,” and we worked on this during Covid. These histories are a series of returns.

I was also thinking about “returns” while you described maintaining the work. The art may be generous, but it also demands a lot of its caretakers; it requires that you physically return to the work in order to care for it.

Yeah, that’s funny—it’s also a physical return. In the most basic way, it underscores the root of our profession, cura, curating as a form of care.

Another way to think about returns involves the ways in which many of us keep returning to Felix’s work. I think it’s because of that beautiful tension in the art, which prompts us to think through the moment in which it was made and the world in which it is exhibited now. It underscores this idea that the past always returns to shape our present.

It’s interesting that people still refer to him by his first name, even those that didn’t know him personally.

Yes, it’s a phenomenon that Glenn Ligon and Joshua Chambers-Letson have written about. There’s also “FGT.” I can’t think of another artist like that. There’s something in the work.

We half-joke that Felix is the third curator, because his work is not only the subject of the show—it’s also the structure of the show.

Claire Dillon

Rome, Italy

April 2025

Claire would also like to thank Josh T Franco for meeting her in the galleries and for his contributions to this conversation.