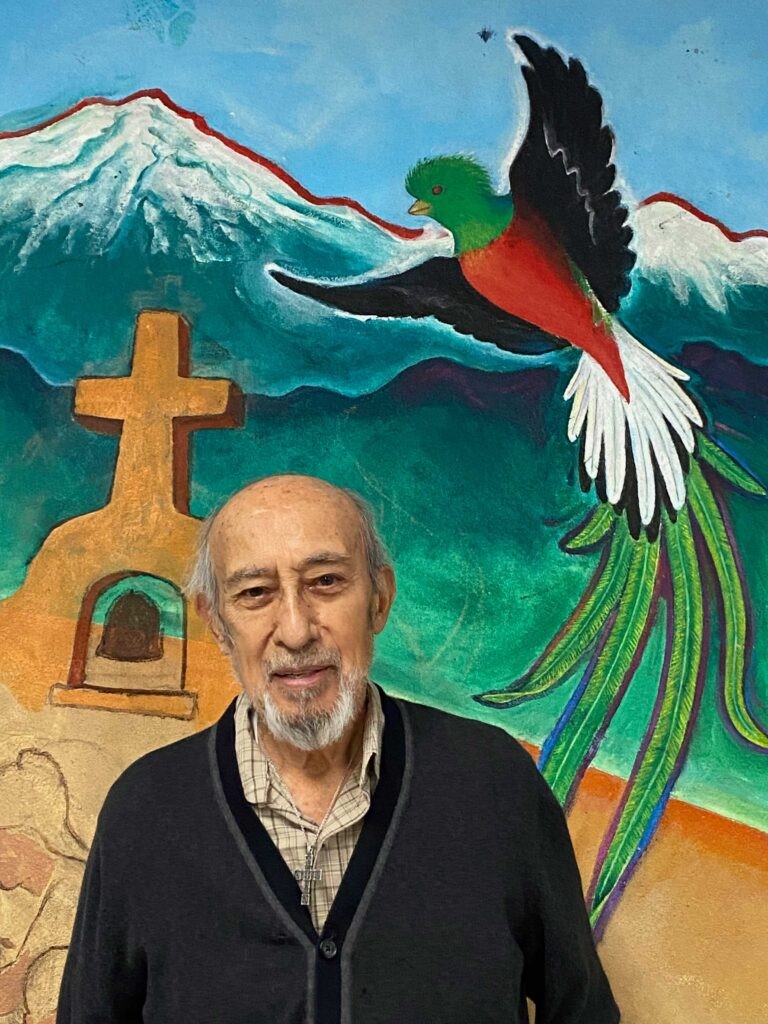

Leo Tanguma (b. 1941) is a Chicano muralist known for his works that integrate Mexican American heritage, spirituality, social justice and autobiographical elements. Born in Beeville, Texas, he began his career in Houston with ambitious murals that advocated for social change. In the 1980s, he moved to Denver, where his public works made waves in the Denver International Airport, and he continues to create murals throughout the Denver community, most recently at Ricardo Flores Magon Academy. This is the second interview with Leo Tanguma to appear on zingmagazine.com, the first was conducted by Rachel Dalamangas and can be read here. Leo will be featured on the ARTiculated: Dispatches from the Archives of American Art podcast, produced by Archives of American Art | Smithsonian Institute oral historian Ben Gillespie.

Interview by Ben Gillespie and Josh T. Franco

You’re coming up on nearly 40 years in Denver—how has your understanding of the Denver community changed in that time? What excites you now in Colorado?

When I moved to Denver in late 1983, the Denver community, especially the Chicano community, was experiencing a severe problem of gang violence. After attending meetings which sought to address the problem, I observed the actions already taking place in dealing with the gangs I was deeply impressed with what I saw. I immediately added my contribution to those efforts by constructing a movable, sculptural mural on gang violence. I designed this mural to be shown in one area, dismantled, and then taken to be shown at another site in order to reach as many viewers as possible. My understanding of the issue developed into an admiration for the city and for the Chicano community in particular.

During the past 40 years, Denver has only increased its kindness towards me. This situation has remained constant as I have seen my work welcomed despite its frequent political or radical content. For example, the following are some of my most political murals:

Beyond This Cross (1986): This was a sculptural mural in the shape of a cross, 33 feet in height by 45 feet at the base, and was exhibited for an extended period at the Denver Center for the Performing Arts in downtown Denver. The painted imagery on the cross was a condemnation of the United States Government’s support for Central American dictators who oppressed and murdered many people using the military as well as death squads.

The Torch of Quetzalcoatl (1989-1990): A sculptural mural 72 feet along a curved base by 12 feet in height tapering down on its ends to 2 feet. This mural was commissioned by the Denver Art Museum in 1989-1990. Its subject was the Chicano Movement and Movement for Civil Rights in the United States.

In Peace and Harmony with Nature and The Children of the World Dream of Peace at Denver International Airport (1993–1995). I painted two sets of large murals with a total square footage of 692 square feet: I was assisted by my daughter Leticia Tanguma as well as a few other Denver artists.

Given Denver’s openness to progressive artwork, I wonder why more Denver artists, especially mural painters, in the Denver area have not seen fit to examine social and cultural issues in paintings and offer them up for the public to enjoy or scrutinize? I call Denver’s stature one of down-to-earth sophistication with tough demands but with high rewards for those who try.

Leo Tanguma, The Torch of Quetzalcoatl, 1989-1990

You’ve described human dignity as a foundational impulse for your work, how would you define it? How have collaborators defined it or changed your definition of it?

My sense of human dignity comes from religious Christian ideals instilled in me by my farmworker parents during my youth. The murder by the Sheriff of my mother’s two cousins at their ranchito in my hometown south of San Antonio, Texas inspired my rebellion against authority. I realized that the social order and its authority over us demeaned, and it often destroyed, our human dignity. What the Sheriff did that day was to attack our self-respect, that is our human dignity, especially since we could do nothing about it. The Sheriff was exonerated in this case as he was in other cases that involved his killing of other Mexican-Americans.

Following the murder of my mother’s cousins, our local community resumed its life, and we were soon back “normal” again: Happy in our homes and our barrio. Later I saw this return to normalcy as our reclaiming our human dignity.

As I matured, I painted mural depicting the struggles of all oppressed people fighting for a better life and thereby for their human dignity. I became aware of the Christian philosophy of Liberation Theology that stressed that Christians must have a preference for the poor and the oppressed. In essence I have been doing this all my life as a mural painter. I am not sure that my example has inspired other artists. Although I have spoken and advocated for an art reflecting not only our community’s culture but also its political struggle.

Leo Tanguma, Beyond The Cross (Detail), 1986

How do nature and the natural world factor into your murals?

I have shown nature in some of my murals. I equate beauty and fragility of nature as something spiritual, something that touches our senses with awe at the spectacular beauty of this mystical creation all around us.

Leo Tanguma, Leticia Tanguma, Cheryl Detwiler, In Peace and Harmony with Nature, 1993-1995, Denver International Airport

David Alfaro Siqueiros and Dr. John Biggers were major influences for your approach to mural making and meaning—how do you hope to influence artists today and tomorrow?

Dr. John Biggers, Professor of Art at Texas Southern University, stated that the greatest experience we can conceive of is the human struggle through the ages. He said, “Our struggle for Civil Rights is part of that monumental struggle for human dignity of which we are a part of.”

David Alfaro Siqueiros told me in an interview with him in his Cuernavaca studio that we Chicanos should not only paint the folkloric and cultural identity of our community, but also the political and social struggle. Siqueiros also referred to leaders and revolutionaries of whom we were aware. He also pointed out unknown and forgotten martyrs and heroes in the human struggles of the past.

At my age I can only say that hopefully my example alone could be of some value.

Looking back on your long career in art and activism, what does “Chicano Art” mean to you today?

Chicano Art means to me the representation of my community’s aspirations for liberation through the mediums of artistic creation. However, the artform which most lends itself to that expression is mural painting.

I have often said that mural painting is our Mexican heritage going back two thousand years B.C. in ancient Mesoamerica. I am not sure about the following being applicable to our Chicano Art, but I suggest that the cave paintings of Altamira, Spain, should be incorporated into our Chicano sense of history.

Leo Tanguma, Leticia Tanguma, Cheryl Detwiler, The Children of the World Dream of Peace (Detail), 1993-1995, Denver International Airport

You often collaborate with young people. What do you hope they take from the experience of creating murals with you?

In most, if not all, of my painting with youth, I use the symbolism or figures which we may be painting in a mural as messages about their intrinsic worth. Often in developing a mural topic to be painted with youth, I point out the importance of what we are about to do. Instilling this mindset at the beginning, our planning inspires those youths to more meaningful ideas for a mural. I suggest that while painting a mural is a fun experience, it can also tell a story or message with their pictures in a mural.

On more than one occasion, I have been approached by middle-aged persons who have said to me “Do you remember me? I painted with you in Arvada Middle School?” Or many other locations where I painted with youth. A particularly memorable experience was when someone said, “Remember me? I painted with you at Platte Valley!” (Platte Valley Youth Services Center, a youth correctional facility). He added “And you talked to me!”

Everyday heroes from many cultures come together in your murals—who or what is a symbol of heroism for you today?

I am inspired by many revolutionaries of the past. But my heroes are my parents, a friend in our barrios of many years ago, and the following very special people:

My sister Enedina who was raped and had a child but continued to work in the fields to help support our family.

My Uncle, Pedro Jarro, who fought in battle in France in World War I.

Dr. John Biggers, my African-American professor at Texas Southern University, who advised me and encouraged me to continue painting murals on the street.

But most of all my wife Jean, who endured more than ten years of domestic abuse from her partner before she met me. She, nonetheless, fought for social justice for others starting in college and has continued in the struggle to the present day. Since I met her over 40 years ago, she guides and inspires my work. Her progressive ideas have greatly influenced me. Beyond that is the person who she is: her ability to love deeply and never expect anything in return. Her love for the oppressed, especially those in our American society who struggle daily for a better life. Her patience and smile always move me, and I thank God for such a love in my life.