Figure and Landscape, 2024, oil on linen, 108 x 144 inches

Juan Eduardo Gomez is a New York artist, born in Bogotá, Colombia. A longtime assistant to legendary artist Alex Katz, Gomez is dedicated to the craft of painting with his own practice— working skillfully in watercolor, acrylic, oil, and charcoal to achieve exceptional works of art. Indebted to painting in the traditional sense, his work is distinctly contemporary, seeking a direct relationship between artist, canvas, and viewer. He’s had three curatorial projects in zingmagazine: “Share” (issue #10), “Rhythm” (issue #21), and “Blow Up: Paintings by Alex Katz” (issue #22). His work is held in institutional collections, including Dikeou Collection, Museum of Fine Arts Boston, High Museum of Art, and San Antonio Art Museum, and has been exhibited at Aldrich Contemporary Art Museum, High Museum of Art, American Academy of Arts and Letters, Art In General, and most recently at James Fuentes’s new space in Tribeca in a solo show titled “Dusky Rainy Sunny,” on view through September 7.

Interview by Brandon Johnson

While I was talking to you at the opening, someone pulled out their wallet with a badge of some type. Who was that?

Oh, that was Lee Quiñones. He came out of nowhere flashing a police badge and asked me to come with him. He scared the heck out of me. The whole evening was so exciting.

How do you know Lee?

We met a long time ago, mid-’90s. My ex-wife, she was friends with many graffiti artists, and he was one of them. I used to see his work all over the place. There was a great show of Lee Quiñones at James Fuentes, that one blew my mind. I spent a lot of time with his painting. There was one at my house, a Speed Racer. I admire him. Such a great guy, a great artist.

Did you ever write graffiti?

No, not at all. But I like the approach of graffiti making, which is like direct painting. You can do it with a roller. There are many people that do it with a brush or spray paint, but it’s just the immediacy. You approach a wall and just go for it. For me, it’s kind of related to skateboarding—you need to practice. It’s very much about the physical, the movement. It’s almost athletic in a way, and it has a lot of thought behind it. It’s subversive. Rebellious.

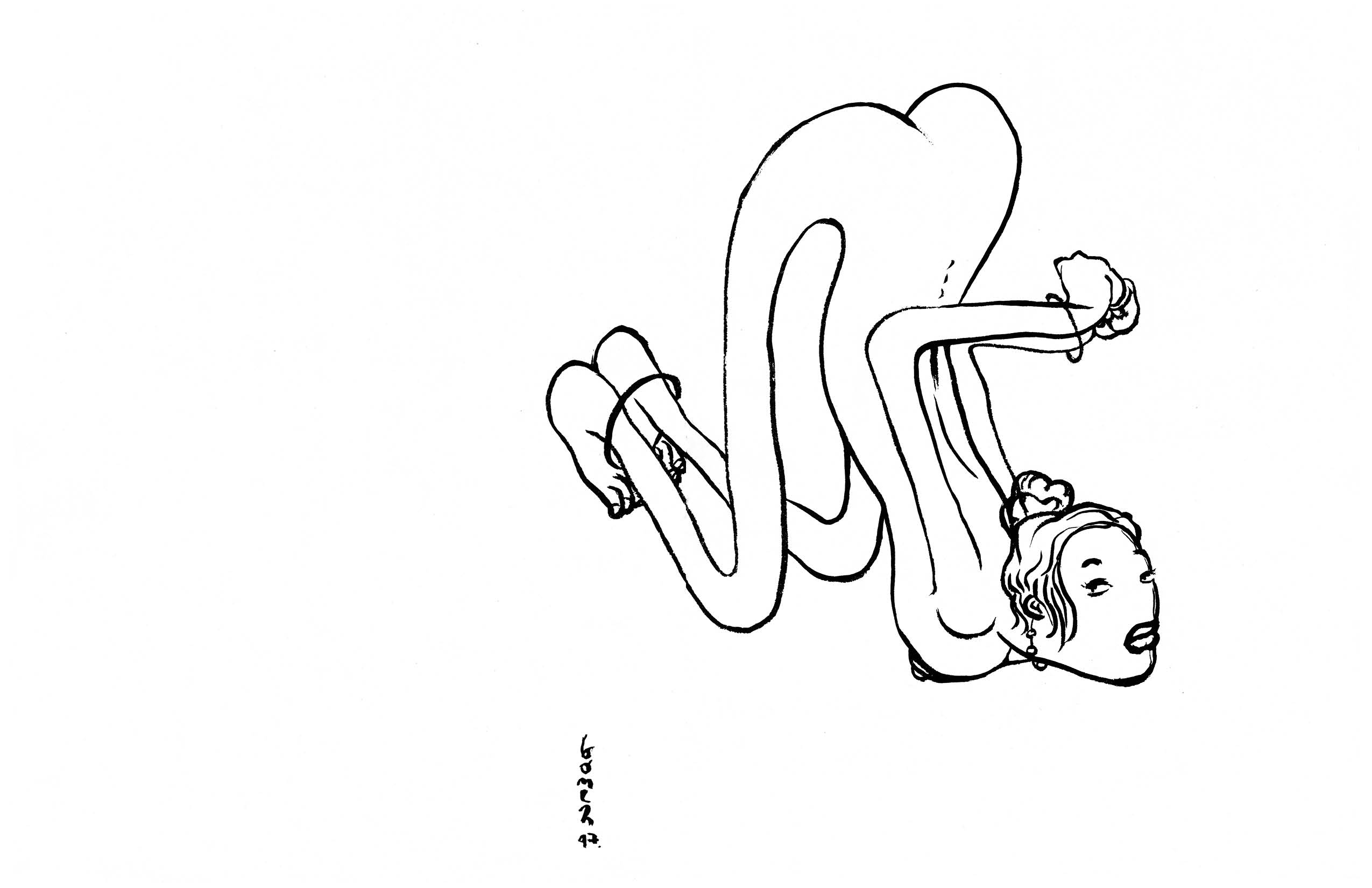

Charcoal study for Reclining Figure 1, 2024

Last time we saw you was at your studio in Navy Yard, maybe two years ago? You had a bunch of paintings, different sizes and styles on the wall, leaning against the wall, turned around facing the wall. When I walked into the show, at first the work felt very fresh and not immediately like something I’d seen during that visit. I remember the flower paintings most vividly, but then started thinking back and could see the new paintings coming out of things you’d done previously. Can you tell me from your perspective, how you arrived at these paintings?

I love painting, and I love painting big, especially. Charcoal and paper is awesome for me because I can keep producing quickly. When the pandemic hit, I was doing large charcoal drawings of human figures. Many things have happened since then, and now I’ve been noticing a sense of evolution while refining a theme. It just pops in and out, effortlessly. I picked up exactly where I left off some time ago. Even the first attempts continue to feel better than when I develop it more. And that’s great because I used to have a sense that you must do something for a long time to become good at it or to have a sense of accomplishment. But in reality, it’s like blinking, or opening a door, a window once, and going back and opening it again. It’s just there, fresh. And it’s not related to time and development. It’s more related to stepping back into it, and you’re on. Like riding a bicycle. The first time you start riding again, it feels great.

Paths that you’ve been developing over the years. For example, painting figures—it probably feels natural for you to just step back into that? You said these paintings were made over the last two months? That’s a quick turnaround.

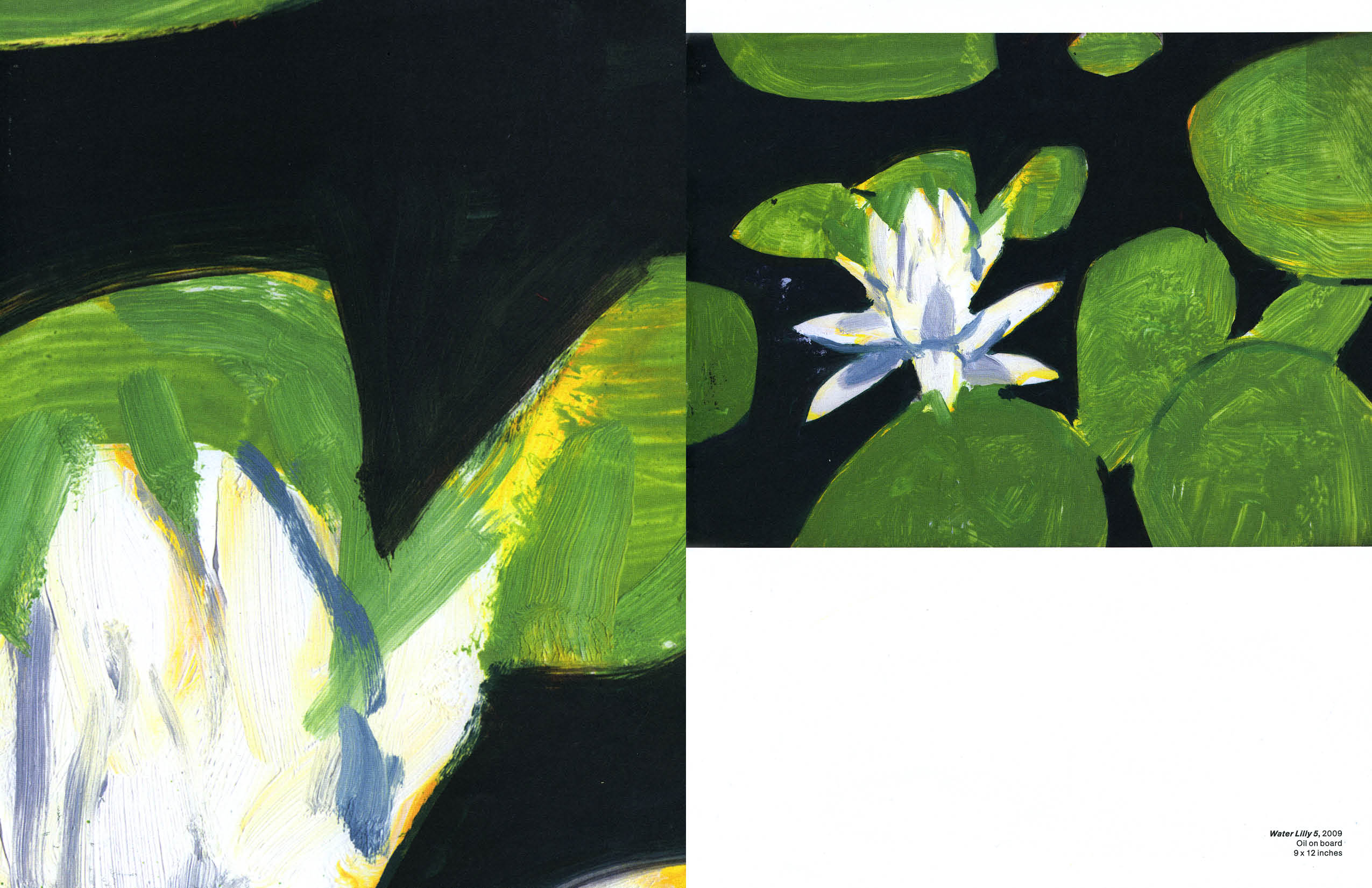

The studio visit from James gave me a lot of energy. So, I set out to do one-to-one scale charcoal drawings of the paintings I wanted. Gardens, a lot of flowers and vegetation, from spending time upstate in nature.

I remember during our visit you were talking about gardens. You mentioned blooming morning glories in your yard or on the street in Brooklyn growing on a fence. And that your grandmother had a garden in Colombia when you were growing up?

Yeah, we were in the tropics and my grandmother was in tune with nature. My grandmother was influential. She had this thing of let’s lay down on the floor and look at the stars. Going to a flower and say, look at these flowers. Look how beautiful it was, when I was two, three years old. And she’s always pointing out things that maybe you don’t really take the time to observe. I’ll always remember her through flowers and gardens, and that feeling of looking at things and appreciating.

Reclining Figure 2, 2024, oil on linen, 132 x 84 inches

The press release from the gallery suggests you “set out to render a landscape or garden—but the human figure repeatedly appeared…” I was curious about this personification of the garden or landscape expressed as the human body. That’s very interesting, sort of a transfiguration…

Ah, you’re using my favorite word—transfiguration. Probably one of my favorite paintings is titled The Transfiguration by Raphael. I do observational work where I study things in a very academic way. I’m also sometimes thinking of something that I believe is important and try to bring it into the canvas or paper, but often I just let things happen on their own. And that’s when it gets most interesting, because I get to experience things that I didn’t know were there but they’re a main subject in my subconscious. They appear in front of me and it’s like looking at myself in a clearer way. It has a lot to do with the moment. And in these drawings the figure came and I just let it be. Then I made several drawings, and each time I increased the size of the paper, the figure expanded—the larger the paper, the larger the figure. I couldn’t fit the figure into the paper. That was the reason why they’re all cropped. That felt unique. I just thought, you know, it wants to be that way. And maybe it’s related to the landscape painting. The body becomes the landscape because it’s not synthesized or a concrete object on a background. It becomes the background and the object at the same time. At our studio visit James asked me how do I imagine a show of my work, the question lingered and helped me focus.

He asked you to consider how the work is experienced in the gallery rather than in the context of your studio?

That’s not something I always think about because I’m just focusing on each painting. I don’t care about the one before or what comes after. I’m not thinking about the paintings in space. Later James invited me to the gallery in Tribeca, which was still under construction. I stood there, and thought about large format paintings. Back at the studio I made large drawings using charcoal as if it was paint on a brush, just like an air guitar painting for me.

The paintings are very large with figures that are larger-than-life. What does it mean for these figures to be so big, taking up the entire canvas, and for somebody to be experiencing that in the gallery space?

It’s really about an immersive physical experience of inhabiting the body. It’s like you’re at a mountain experiencing the landscape and you say, I want to remember this forever. You ask someone to take a photo of you, and then you go back to the city, and realize the photo doesn’t convey the moment. It looks artificial. The scene could seem diminished, and the sense of the environment is not there.

Vertical Figure, 2024, oil on linen, 132 x 84 inches

Is the scale of the paintings tied in with the body as landscape? For example, the vertical painting of the male figure that is kind of contorted and upright. You can get lost in the different parts of this figure’s body…

The paintings are an in-person experience, it’s good to be in front of them to get the full effect. The sensation, the landscape of the body. I wanted to convey the feeling of the body, not the body in an anatomic or concrete way. Sometimes I aim to encapsulate the subject. This time I wanted the sensation. So, I allowed distortion to acknowledge feeling of the body. I wasn’t paying attention to the proper anatomical placement. Like you say, it’s much more related to the interpretation of a landscape that way. The hand, the muscle, and the experience—I’m trying to forget about the appearance and legibility.

There’s a sensuousness in these paintings that’s not necessarily erotic, but in that it’s involved with your senses, how you sense a body. Your projects in zing #10 and #21 were erotic, but I feel like there’s this line through your work of sensuousness, of a living body, a body in motion or in action, and how it can be experienced rather than like a corpse just there to be observed…

I didn’t want to glorify it or fetishize it nor denigrate it. I just wanted it to be how I was experiencing that journey through the body. The paint was helping me make that trip.

Painting from “Rhythm” zingmagazine #21

The garden is a symbol of innocence, purity, fertility, life. These characteristics are personified in your paintings with the same sensuousness of somebody like Michelangelo, often credited as an artist who understood and celebrated the body. I see some relationship there—his bodies are contorted, there are muscles, and vitality.

I think I agree with you. Michelangelo’s works are a celebration of the body. You can feel his sincere involvement with what he was doing. The David blew my mind.

When did you go there?

A long time ago. I saw The Slaves, the David. So great. There are other sculptures and paintings from the Renaissance with incredibly technical achievements, which are impressive, but they don’t have the sincerity I find in Michelangelo. His approach is personal. I feel the emotions attached to his carving. He’s completely immersed in the creation.

He was also working large. For example, the Sistine Chapel. He had to make those figures very large so people can see them from the ground. For him painting, the body’s larger than life.

Absolutely, that’s great to think about right now. How are people going to see it? How visible is it? Graffiti writers think about that too.

One detail I noticed in the show is that a flower made its way into one of the paintings. During our visit a couple years back, you showed us an amazing flower painting that was very delicate, expressive, colorful. In this show a hand holds a similar flower. Is this a nod to things that came before, things you were working on? Is this a little piece of history that made it into a painting?

Yes. Are you inside my head or what? It comes from many things coming together in one place, not one thing in particular. I never work from a single idea.

It happens on the surface?

It happens on the surface. And then I start seeing all the references, like, maybe that’s related to this occasion or that one. And that painting has many references. But someone who is special to me was having a birthday, and I forgot about it. I had a little remaining piece of linen, so I took a sharpie and I drew a hand with a flower, holding it, and I gave it to her for her birthday.

Hand and Flower, 2024, oil on linen, 96 x 72 inches

So, it came from that experience?

Not directly, but I see the reference. Another might be Tarkovsky’s film Nostalghia (1983). This guy has a candle, and he’s trying to walk a path without the candle going out. He tries to walk across with the lit candle to the end of the path he set for himself. The wind blows and he has to go back and light it up again, trying to get across. And the wind keeps blowing the candle out, like Sisyphus maybe. The flower in that painting, I’d say it has to do with the feeling of wanting to keep going. Fragility.

The flower is being held out to the viewer in a way, almost being passed to whoever’s beholding it, which I also hadn’t really thought about until now. That’s beautiful.

The painting is not necessarily about these things, but I’ll look at it like a mirror and see these references in it.

I feel like your work is criminally underrated. But James Fuentes is the perfect gallery for this show in a lot of ways, he works with serious painters who take the long view. You’re in the right company there.

James is important and Devon [Dikeou] also. So grateful.

I’m not sure I ever got the whole story on how you met Devon. Zing is down the block from Lucky Strike and she would go there all the time. That’s how you met?

I was working at Lucky Strike and she gave me an opportunity in zing. Imagine how cool that is, she looks at me as an artist. Big accent back then, even more than now. Less of a vocabulary. And just for her to say, let me see what you’re doing. That’s a huge deal.

Devon’s always done that with zing, giving opportunities to emerging artists. The drawings in issue #10 were simple, of bodies and figures.

I was mid-twenties. Those drawings were like handwriting and are actually very similar to process of making the charcoal drawings I’m doing now. I love that project.

Drawing from “Share” zingmagazine #10

One more thing I was interested in is that you studied at the Art Students League of New York, where I assume you were doing a lot with the figure?

I had a student visa. I had to be registered in school and show up full time. I was at the League, it was a very academic place. I had no stipend or anything. I was working, doing moving jobs at a trucking company. They had night classes and early classes so I could move my schedule around every week in a way that I would make the quota for my hours. And obviously, I was happy to draw and paint. And they helped me. I got a scholarship.

When did you start working for Alex Katz?

Early 2000s. I work with him where he produces paintings. I was tired of doing restaurant work and I quit. I was walking down the street in Soho and ran into Lyle Starr, a painter I know. He said that he got offered this job with Alex Katz, but he couldn’t do it. But if I was into it, I could go meet Alex and maybe I could get some work.

Spread from “Blow Up: paintings by Alex Katz” curated by Juan Eduardo Gomez, zingmagazine #22

I’m sure you’ve learned a lot from him?

A lot. Alex is an interesting guy. He’s complex. It’s been great. He’s a New York artist, the influence he’s had in the scene and the influences he had from the scene are all alive in him. And it’s been good to be around him. His approach to painting, living a life as an artist, how to be professional, production, what to prioritize, and all that has been extremely helpful. He’s been a great support. I learned about myself as an artist.

Anything else you’d like to say?

That’s all. Thank you.