In July 2023, Denver, Colorado will witness the grand debut of an ambitious city-wide festival called Month of Video (.MOV), orchestrated by local artists Adán De La Garza and Jenna Maurice. From DIY venues to massive outdoor projections, .MOV aims to present an array of artists and genres across the video spectrum. As artists whose practices are deeply embedded within this under-represented medium, De La Garza and Maurice have a history of curating accessible programming for video work that is cutting edge, critical, and beautifully strange. We chatted about their early influences, personal practices, and of course all things .MOV.

Interview by Hayley Richardson

Can you give a general overview of your art practice(s)? Where and how did your work take shape, and what are some recent developments/changes you’re currently addressing?

Adán: Some older kids in my neighborhood introduced me to different subcultures really young. Like, I had a Slayer tape and a Terminator 2 skateboard at 7. So my early introduction to art was more through channels of skateboarding, metal, comics, video games, MTV, and Nickelodeon.

My introduction to photography started in middle school when I was enrolled in a class that rotated between black and white darkroom photography, literal card games (think solitaire and gin rummy as a class), and stagecraft. I was placed in this class because I ran out of elective options or was late registering. Initially, I thought I would move into skateboard photography, but I never really got serious and never was super good enough at skateboarding. In my late teens and early twenties, I made videos with my friends doing stunts and blowing stuff up in the desert, and that definitely laid the foundation for my interest in video and incorporating elements of risk-taking, failure, and absurdity into my art practice.

I kept taking photo classes through high school and got a scholarship to Pima Community College, but I wasn’t entirely sure what I wanted to study, so I enrolled in screen printing and photo classes (perhaps a theme is emerging here, haha!). It wasn’t until my twenties that I actually began consciously pursuing art. I had one class with a particular grad student who introduced us to more conceptual, experimental, anti artworks, and I was really resistant to it at the start, but by the end of the semester, I was totally a different person. Up to that point, the majority of high art I was exposed to was about “mastery,” “genius,” and the worshiping of some sort of authority… that never really resonated with me. These works were democratic, chaotic, and more politically aligned with my views. After that, it was something that I gradually kept doing more and got in front of the camera eventually.

I work predominantly in Sound, Video, and Performance Art, and more recently, I’ve been making speculative fiction works about the desertification of the earth, a video about tree canopy density in Denver and how it correlates to income, racism, regional temperature averages, and the history of land ownership, and some new sound performances. I hope to go on a solo tour through the southwest in September to an exhibition with my longtime homies at Everybody in my hometown Tucson, AZ. I’ve always got a few zine projects in the works as well…

Jenna: I was homeschooled (which I loved) but didn’t take any art classes in high school, so I didn’t really have an entry point for anything in art that wasn’t just painting or drawing or sculpture (and I wasn’t really into those). My sisters and I were super into theater and saw a lot of live theater and also participated in live theater all through high school. As a child, I was always interested in our home video camera. My sisters and I would shoot lots of things on that camera and then be delighted to watch them back, but never considered any of that “art.” I remember the day that I looked into a 35 mm camera for the first time when I was 15, and I remember looking through the lens and seeing the frame and the shallow depth of field, and realizing how powerful it was to be able to curate the world through a rectangle. Somehow it was really different than looking through that home video camera. And it impacted me so much that I began taking photographs and then began looking into what being a filmmaker was like. So I went to undergrad for photography and filmmaking, and in grad school, video really entered my practice. I realized that I didn’t want to make stories for people but would instead like to communicate complex ideas that unfold over time. And that’s basically how video art functions for me. I remember while I was in undergrad- going to New York for the first time in my life and seeing a Bill Viola retrospective at a big Museum there and thinking, “Wow. This is really different from films. and I love that. It’s about communicating ideas that seem deeper than stories that sit on the surface of things, and it’s super weird and surprising”.

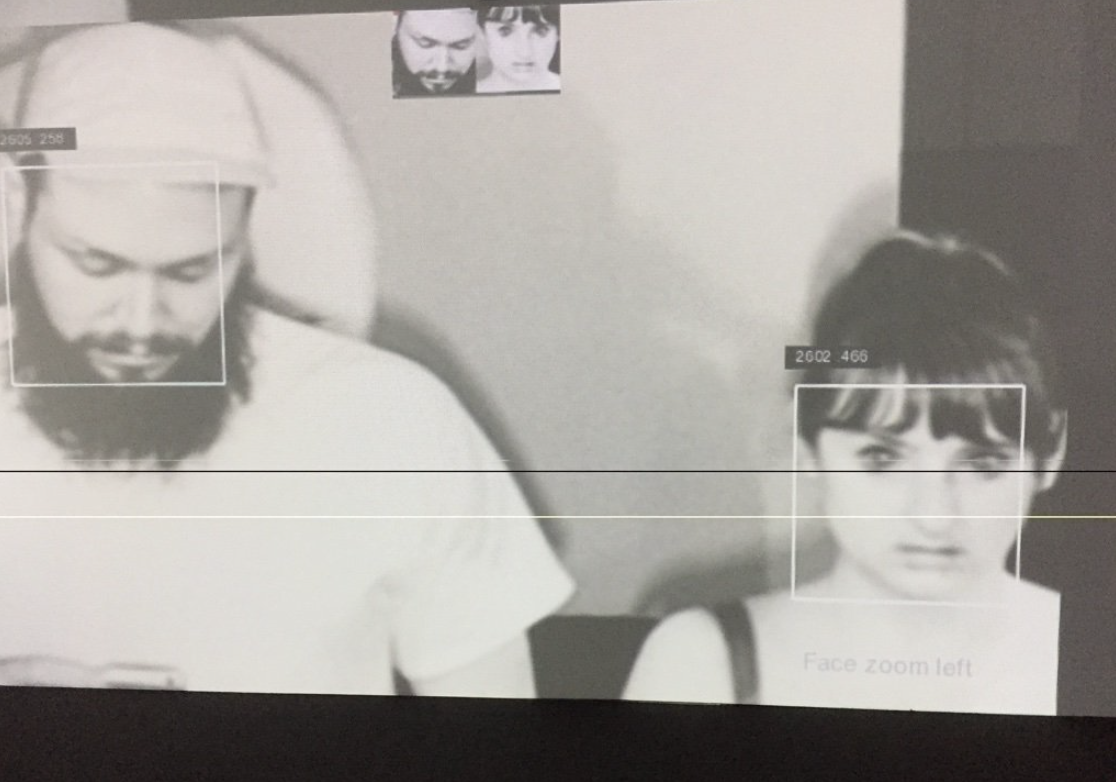

My practice has always been about relationships and relational dynamics, probably because I have a big family, and we were always really close growing up. It has evolved to also include nonverbal communication as a central point of inquiry. Performance and using my body to communicate something came into play during grad school when I took a performance art class that changed how I understood what performance could be and how the body could be THE tool for communication. So now my work involves video, performance, and photography, and it deals with ideas concerning relationships (with myself, others, the past, and the landscape), non-verbal communication, and the language of the complicated human experience.

One of my most extensive projects (Concerning the Landscape: A Study in Relationships) is a series of performances for video in particular parts of the landscape where I try to build a relationship with the landscape using non-verbal or pre-verbal techniques (such as reaction, mimicry, etc.). I have been working on The Archive of Things series for the past few years. It’s an ongoing project documenting the world through the practice of Lumen Printing. The work in this series explores the question, “What can the sun reveal about objects that humans cannot see with their eyes”? These images are lumen prints- a process where objects are placed directly on black & white paper for darkroom prints and taken out into the sun for hours at a time. The long exposure from the sun lets the sunlight penetrate any part of the object that is not entirely opaque, resulting in a representation of the thing that humans cannot see by just simply looking at the object. Over a period of hours, the sun travels through the object and records details within the object, revealing hidden truths about these everyday items we encounter. The sun also interacts with the emulsion on the darkroom paper, creating colors from where there was only the possibility for black & white printing.

I am also currently working on a video essay that explores the complex topic of “grey areas” and how these areas can be viewed as both places of challenge and chaos (because they are undefined) as well as places ripe with possibility (also because of this area of no clear definition). In this way, my practice is now exploring “relationships” with situations… and not just people and the land. 🙂 I am currently in residence at Redline Contemporary Art Center.

Jenna Maurice, Traverse, at Union Hall curated by Esther Hz

In addition to your individual practice(s), you also have a history of community engagement via curated screenings for the public. Has interfacing directly with a public audience and providing a platform for other artists influenced your own practice at any point?

We both view programming/curating as part of our artistic practice. As contemporary artists, we feel it is our responsibility to champion other ideas and approaches outside our practices. Especially when the mediums and ideas you work within are under-represented in your community. Showcasing time-based works regularly is also a way to maintain an artistic community in Colorado. If you feel like you have no opportunities to show or discuss the work you make in your city, you’ll probably move somewhere else that has that… and might even be cheaper.

I think we both have been able to make significant friendships through shared experience and interest in art. So programming/curating has always been an extension of those goals where we get to share the experience and ideas of others with the community we are in. I think our dream jobs would be to make things happen with our friends that are larger than us, and .MOV has been a way for us to accomplish that desire, be it outside of our day jobs.

In July 2023 you will launch one of your most ambitious projects in Denver Month of Video (.MOV). Tell us how this project developed and what we can expect to see.

Month of Video is a culmination of a few dreams of ours. We are both video artists and just want to see more video art in our city. We wanted to present a whole month where video is the focus and see video exhibited in as many art spaces in town as we would get on board. In Denver, one can consistently see painting/sculpture/photography in art spaces. Video seems to be a bit more of a rarity, so we wanted to be able to go see video art at a bunch of places for one month. We’ve never run a festival before, but there is always a first for everything. 🙂

We also wanted to highlight the different forms of video art, creating access points for things we wish we could have been exposed to earlier in life. The whole festival is based on this idea of making space for time-based works that engage with many ideas and approaches to making work.

So, we have some specific exhibitions for .MOV that focus on these different forms. We also have some really rad friends who are experts in particular realms of video, so we asked them to curate some of these shows. For instance, Understudy Gallery is having an exhibition that highlights performance for video, curated by Quinn Dukes- the Director of the art fair called Satellite. This is a very particular type of performance art that is usually enacted in a specific location, and the only way to document it is with video. So the final piece of art these artists can display is video, but the initial performance act is the communication. We are also highlighting the genre of art video games through an exhibition where visitors can play all of the games on view (this exhibition is curated by a collective that Adán started called Dizzy Spell). Along with this exhibition, we invited a video game scholar (and dear friend), Nicholas O’Brien, to curate a screening based on videos that use game engines in their creation.

Signal Culture (a residency focused on tool-making and video research) recently moved from upstate NY to Colorado, so we are having them program a screening of work from their alumni to showcase the different work happening there.

Another show we are super excited about is one we are curating for Redline Contemporary Art Center from the main contributors of a public secret society called New Red Order. The show- “New Red Order: Crimes Against Reality”- examines the contradictions inherent in a society built on both the longing for indigeneity and the violent erasure of Indigenous peoples, lands, and ways of life. NRO provocatively questions how these desires can be channeled into something productive, sustainable, and transformative. The show includes a selection of video work that invites viewers to critically engage with the complexities of settler colonialism, cultural appropriation, and enacting of indigenous futures.

Check out the website for all of the info denvermov.com

New Red Order, Crimes Against Reality, at Redline curated by Adán and Jenna

You both describe being exposed to the creative arts through pop culture, school, and family at a young age but also express that video is a particularly under-represented medium. What are some additional resources you would recommend or hope to see made accessible to individuals interested in video?

Adán:Realistically the places I would like to see time based arts more is K-12 education and just at more art museums. Most students are first exposed to time based arts in college and we can start having those conversations way earlier. This limitation is often echoed in museums and galleries and that has an effect on what is deemed valuable and acceptable culturally outside of those institutions as well.

Jenna: I totally agree. We both worked in academia for longer than a decade and consistently saw our students having no exposure to time-based arts before college.We would like to see contemporary art “normalized” in the way art history is taught before students enter college. It would be so rad if students were already familiar with artists who are alive and making work about important topics using time-based mediums, and not just familiar with dead white-guy painters. So, access points as well as normalizing video within exhibitions is a great way to help with this.

Is there anything else you’d like to share here? Upcoming projects or places where we can keep up with what you’re working on? (aka shameless plug portion!)

Collective Misnomer might keep doing stuff.

After MOV comes to a close, Maurice and De La Garza will continue their respective video art projects. One of Maurice’s current works-in-progress includes a video essay examining the prolific possibilities within ambiguous “gray areas,” or domains lacking clear definitions. De La Garza, working on “video pieces focused on climate change and the desertification of Earth,” will also embark on a solo tour from Denver to New Mexico and Arizona this September on his way to exhibiting his work at Everybody Gallery in his hometown of Tucson.