Walter Robinson in his studio, photo by Marina Tychinina

Interview by Devon Dikeou

Let’s start with your show at Air de Paris, “C’est le destin bébé” . . . It is like a great “best of” album . . . It had pulp romances, a Vietnam scene, a burger, cash and a salad painting . . . And a series of button-down, folded shirts . . . How did you edit the selection . . .

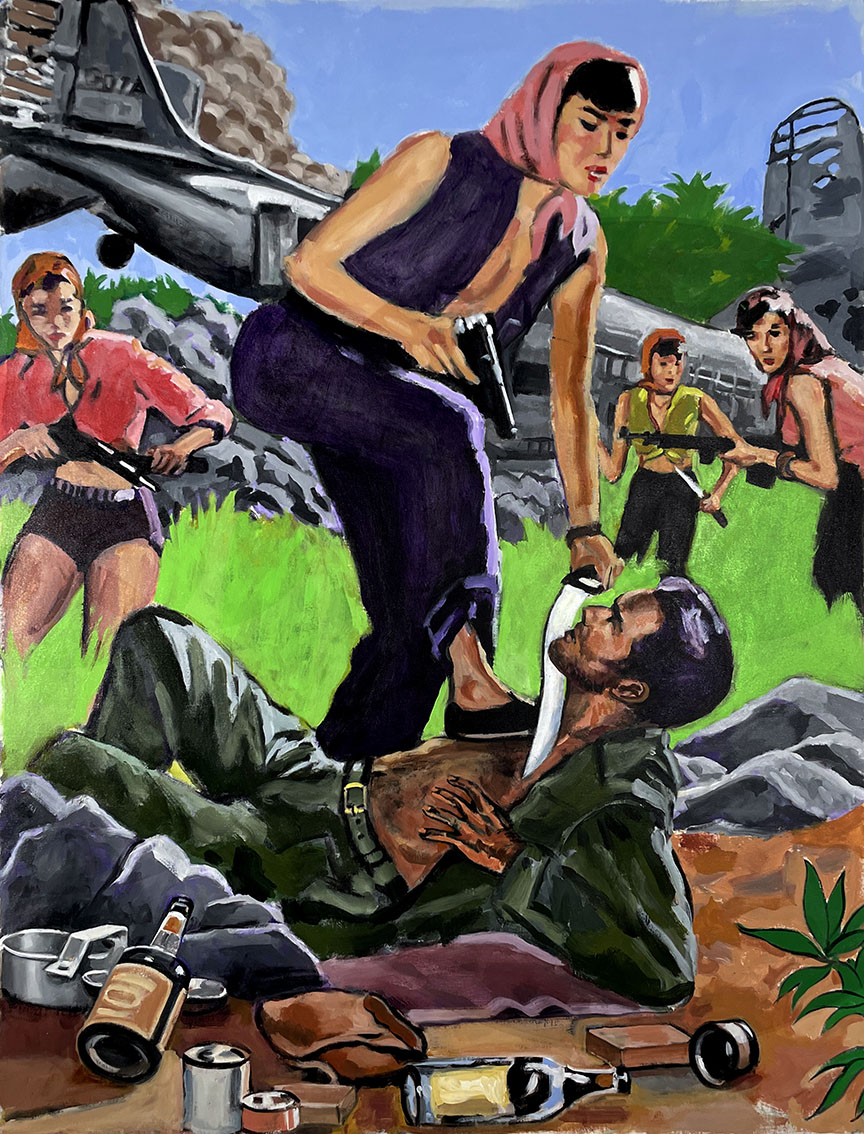

The dealers at Air de Paris, the legendary Edouard Merino and his partner Florence Bonnefous, made the selection from inventory. They’re awesome. They took some works on paper too. The new gallery space, in a development in the Romainville suburb, is beautiful, and their installation was sublime. They took my first colonialist painting—it’s a new series—which is six feet tall and shows a female Vietcong soldier holding a bayonet to the throat of a downed US flier, to FIAC and sold it. Art fairs sell art!

Vietnam, 2021, acrylic on canvas, 80 x 60 in, courtesy Air De Paris

Why shirts . . .

You know the shirt paintings? I first showed a few with Kai Matsumiya on Stanton Street, then did a solo show of 28-inch-square versions at Charlie James in L.A. Beth Rudin DeWoody bought one; she single-handedly supports the art market. I was psyched when Air de Paris wanted a bunch of them—the French have a thing about fabric and art— Supports/Surfaces, you know? I have long raps about all of my series, you really want to hear it? OK, try this: I paint a lot of sexy girls, in the studio I’m surrounded by images of women—you know, no one is really interested in men as a subject, not men OR women. But I felt bad, I don’t want to seem a complete dog, so I needed a masculine line, for balance.

So the thing about the shirt paintings, is that they’re MEN’S shirts, so they’re male paintings. What’s more, the images come right from the catalogues, or more typically from advertising emails, and the shirts are all flattened, folded and squared off. They’re pinned down, baby, can’t move at all. They’re just torsos, figurally castrated! Funny, no? Oddly enough, these days the clothing merchants have stopped advertising shirts that way, all folded and pressed. Now they picture them loose, as if worn by an invisible man, or even on a model.

Want more? Here’s a partially coherent text about the series that I wrote a while back:

The shirt paintings are about abstraction, the kind that Marcia Tucker featured in “The Structure of Color” at the Whitney in 1971, a show that included artists ranging from Rothko and Newman to Noland and Stella. It was an exciting exhibition, just about the first and last to survey structural abstraction. My shirt paintings are a way of joining that club, taking part in that spiritual quest, joining the ineffable world of magical color and structural form, while at the same time making a little joke about what is after all a bit pretentious.

So, the shirt paintings are poised on the threshold between the spiritual and material worlds. If you think of it, it’s nutty, dressing in abstract patterns, checks and dots and plaids, so popular and so commonplace, geometrical patterns that in addition to serving a mundane decorative function also signal some kind of cosmological order. Polka dots imitate the heavenly cosmos. A plaid may not reach to a heavenly gyre but it certainly can indicate an ancient genealogy. It’s an atavistic anthropology of dress.

The shirt paintings are an extension of my “normcore” series, which are paintings based on images taken from department store ads and mail-order catalogues—models and such, posed to sell the clothes they’re wearing. My models smile at you. Who does that? This kind of material comes already designed for visual appeal, and already calculated to sell. I don’t have to do it! What a relief.

Typically normcore works partake in various ways in what I like to think of as the consumerist utopia. We live in a world filled with resentment, racism, stupidity and hate. The consumerist utopia sells us on the idea that a better world is possible. All you need is a little dishonesty.

That’s such a long answer. I have much more. You know Lands’ End has a “Friends and Family” ad that shows a lineup of four women, two men and four kids. It’s secretly polyamorous! All white and blonde, my people.

Oxford Dress Shirt Lands End, 2016, acrylic on paper, 12 x 9 in

For that matter why any of the series . . . Is it always sex and death with you . . .

Not so much death. Though I have a great artist portrait taken by Marina Tychinina of me lying flat on my back on my studio floor, clutching my heart like I had an attack.

There’s a famous story of you getting a six pack of beer going to the studio and maybe having a few, and painting it, similarly buying a Whopper and taking it to the studio and enjoying, then painting it . . . Both the beer and the burgers became series or parts of series . . . talk about series and serial.

Not famous just a little joke, from the ‘80s, when I was still drinking. I’d buy two six packs as still-life setups, and start drinking and painting at the same time, so the pictures would end up depicting only four or seven bottles or cans. It was a literal search for the spiritual in art.

It was a color exercise as well—burnt sienna (Guinness), cadmium yellow light (Miller), permanent green (Heineken), and red, white and blue (Budweiser). And once again, the object’s appearance had already been maximized for market appeal. Big beer clientele, I figured. Painted them on chipboard and sold a ton at $50 each.

Two Six-Packs (Heineken), 1983, acrylic on chipboard, 20 x 30 in

And that’s before I read your recent catalogue, “Works on Paper 2008-2020”. . . A groovy catalogue aptly titled just that . . . Are the works on paper studies or independent works . . .

I put that together myself, in a burst of initiative during the pandemic. It’s a sampler of all my series, of which there seem to be many. A kid named Erin Knutson did the design and handles the printing; she’s brilliant, Elle Decor just hired her. Richard Prince let me put Fulton Ryder as publisher. And Sarah Nicole Prickett wrote an awesome fiction to serve as the text, about a male artist who has a visit from a critic writing a review, but the artist murders the critic and writes and files the review in her name. Didn’t really happen. The mag is officially distributed by Printed Matter. I have to bike over 15 copies tomorrow.

And these series are painted from real life, in plein air . . . The pinup girls or harlequin covers those would have to be painted from source material . . . No? Please talk about the differences . . . Both in the physical sense of painting and constructing a painting . . . And what then the painting evokes.

No no no it’s all faked, I paint from projected photographs, in the dark. Painting in the dark gives the best art effects. It’s all from media sources, or photos I take. Basically, I have no imagination or skill, don’t tell anyone. I just pass things along, things that want to be fine art.

Kill for Me, 2021, acrylic on canvas, 24 x 24 in

Now the candles, does the candle expire before the paint is dry, or the other way around . . .

Candles are supposed to be mystical, otherworldly, spiritual, you light them to god in church, they mark religious devotions, ceremonies of life and death. Richter paints that kind of candle. All my work is about desire. My candles are carnal, not spiritual. They’re stock images that Asian massage parlors use to set the tone in their ads. They’re about the senses, about touch.

Speaking of burning candles, as your work came of age in what we like to call the Pictures Generation . . . Place yourself and your work within that context then and now . . .

I’m an ‘80s artist and proud of it. I started painting copies of pulp paperback covers in 1979, and had my first show at Metro Pictures in 1982. The brilliant Helene Winer just called me up and asked if I had anything to show. I knew her from the ‘70s, when she directed Artists Space, one of our hangouts. It was next door to our loft on Wooster Street.

Spa Candles, 2018, acrylic on canvas, 36 x 36 in

And since we’re interviewing you within the context of zingmagazine . . . Let’s visit your history beyond the canvas, in the role of the art critic, writer, editor, publisher, raconteur . . . As a prolific writer critic at Artnet years you were trailblazer of how art is reviewed, disseminated, and consumed in the then new realm of internet publishing . . . How if at all, did that effect your art practice . . . And of course, your writing practice . . . Your viewing practice . . . Your critical practice . . .

The art world loves writings by artists, but great artists who are good, practicing critics, that’s fairly rare. Fairfield Porter is perhaps the most famous. I usually joke that a critic’s job is to be an expert on everything, while an artist’s is an expert on one person, themself.

And you’re a founder of Art-Rite, ‘73-‘78, the name sounds so ‘70s , like Diet-Rite . . . speak about founding/publishing that . . . What are some of the memories both fond and otherwise that fuel your recollections of an incredible time capsule . . . As all defunct or sleeping magazines eventually become . . .

Art-Rite we did in the ‘70s. Kids in their twenties can do anything. We were populist, whereas most art mags—not yours!—are snobby. David Frankl wrote an astonishingly friendly report on the mag in Artforum years ago. Now Art-Rite been collected into one huge tome by Primary Information, the publisher that specializes in such exhumations. It has no index, so you can’t simply look up your name, you have to read the whole book.

When the East Village art scene blew up in the early ‘80s, I got a job as art editor at the East Village Eye. We had a scandal, Waltergate, the details of which I will spare you; a hack artist yelled at me for reviewing his show merely by looking in through the gallery plate glass window; and I wrote the only contemporaneous review of Richard Prince’s Spiritual America show on Rivington Street. And I met so many great artists, Mike Bidlo, Keiko Bonk, Luis Frangella, Steven Lack…and Carlo McCormick, the lowbrow art expert and nightclub celebrity. I was his driver.

At the same time I had for years a part-time job compiling art news for Art in America. I wasn’t a reporter—in fact I hated phoning people up and asking embarrassing questions—and knew nothing about the art world or anyone in it. A typical art mag hire: if the kid is dumb enough to want the job, it’s his!

My big break as an art critic and editor came in 1996, when I was hired to run my own show—Artnet Magazine. The digital revolution changed my life. I wrote so much. It’s insane. And it’s all still online, if a little difficult to find. I unleashed the great Charlie Finch like a loose cannonball onto the rolling decks of the art world. I think today Mary Boone still thinks I’m him. And I published Kenny Schachter’s first episodes of his Art Dealer’s Diary. He’s gotten so much better at it.

I did that for 16 years, then Artnet shut the mag down. What a boon for me! Why had I been sitting in front of a computer all that time, an easel is so much more fun. Now my art career is on fire. But I don’t regret my white-collar days at all, especially when it comes to Social Security. Thanks to those taxes they took out of my paycheck, no matter what, I get a fat direct deposit from Uncle Sam every month, enough to live on if push comes to shove. Don’t touch my Social Security!

Even though the awards season has passed, one last question . . . House of Gucci or Spencer . . .

Jeez, I dunno. Lisa makes me watch “Grace & Frankie” endlessly. For octogenarians, they sure drink, drug and hook up a lot. Something to look forward to.