Since 1989, Craig Dykers has established architectural offices in Norway, Egypt, England, and the United States. His interest in design as a promoter of social and physical well-being is supported by ongoing observation and development of an innovative and sustainable design process. As one of the Found Partners of Snøhetta, Craig has led many of Snøhetta’s prominent projects internationally, including the Alexandria Library in Egypt, the Norwegian National Opera and Ballet in Oslo, Norway, the National September 11 Memorial Museum Pavilion in New York City, the San Francisco Museum of Modern Art Expansion in California, and the Ryerson University Student Learning Centre in Toronto, Canada. Recently Craig has led the design of the new pedestrian plazas in Times Square and The French Laundry Kitchen Expansion and Garden Renovation in Yountville.

Interview by Brandon Johnson

Your work as an architect is well-known. But your project “Observationalist” in zingmagazine #25 features your photography. What sparked your interest in this medium?

Photography in and of itself is not a standalone technology for observation. I use multiple methods of observing people, activity, and things. Sometimes I sketch, sometimes I commit things to memory, I might be listening to sounds around me so I have recorded audio in the past. And the way I use photography is to capture a very quick snapshot of something. If I need to move quickly, the camera can capture something that I see and allows me to continue moving. Whereas sketching and other types of technology take up more time. I would say that it’s more about capturing moments in very quick succession. It’s a form of note-taking. I don’t see these photographs as a form of artwork or a representation of the photographic medium. It’s the content that is driving it. I am not much of a photographer otherwise. It’s very important to have the right kind of camera. So as cameras became digitalized, to a certain extent it became easier to take these types of photographs. You can be walking and a take a photograph in a different direction, so you never need to hold the camera to your eyes. It’s just more relaxing. Not only for me, but also for people on the street. As soon as you put a camera to your eye it changes the context. I’m trying to capture things as much as possible exactly as they are in that moment in time without preconceptions. Free of the distraction of the camera to the subject or my own artistic intent. When you’re walking with a camera at your waist, it’s very hard to control. You’re not thinking about how to frame the photo. You just snap it. With a couple of those photographs it does amaze me sometimes when you look back at them after you’ve taken them that you’re able to capture an image that seems well-balanced or seems to be as if it were posed or at least framed in some way. I think that’s an interesting point. You can use a quick response technique to create something aesthetically appealing. There’s something about intuition, and not just of the mind but of the body.

“Observationalist” gathers your conceptual yet casual photos of people and things, organized in loose, and often humorous or absurd, association. Had these associations crossed your mind previously, or did it materialize more as you organized this project?

I would say more intriguing to me is not one image in itself, but the comparison of the images to each other. Many of the photographs are of humans. And many of the photographs are of objects that humans make or acquire. The artificial world and the human world being compared to one another. There are invisible strings of meanings between them. Sometimes I try to make those connections more obvious. It tells us something about intimacy, which is a challenging subject. For those of us that live in cities, intimacy is a luxury. That’s part of the thinking for those images being next to each other. Again, I don’t see these entirely as works of art or photograph. I see them as fictional narratives. I don’t very often show them. The last time I did that, by framing them and sticking them on the wall, would make it seem like a photograph, which isn’t necessarily what they are meant to be. So I printed them very, very small, about the size of a thumbnail, and in a strip, like a ribbon. From a distance it just looked like a thin colored line, but when you got closer could see they were photographs. In order to actually view them I gave people prescription glasses that I found at a junk sale. The prescriptions would different, so you would need to stand closer or further accordingly. Then you could go along and see these images magnified. There were a couple different kinds of frames. Some were horn-rimmed, and others 19th-century wire-framed. You could test out a couple different pairs. In any case, you had to get very close to see the pictures. But the point was that it was a different experience than seeing them in a gallery on a wall.

I can see why this would work given their sequential nature. And I can see why it worked so well for our format as a magazine, which is also sequential in nature. Each photo has its own story as well.

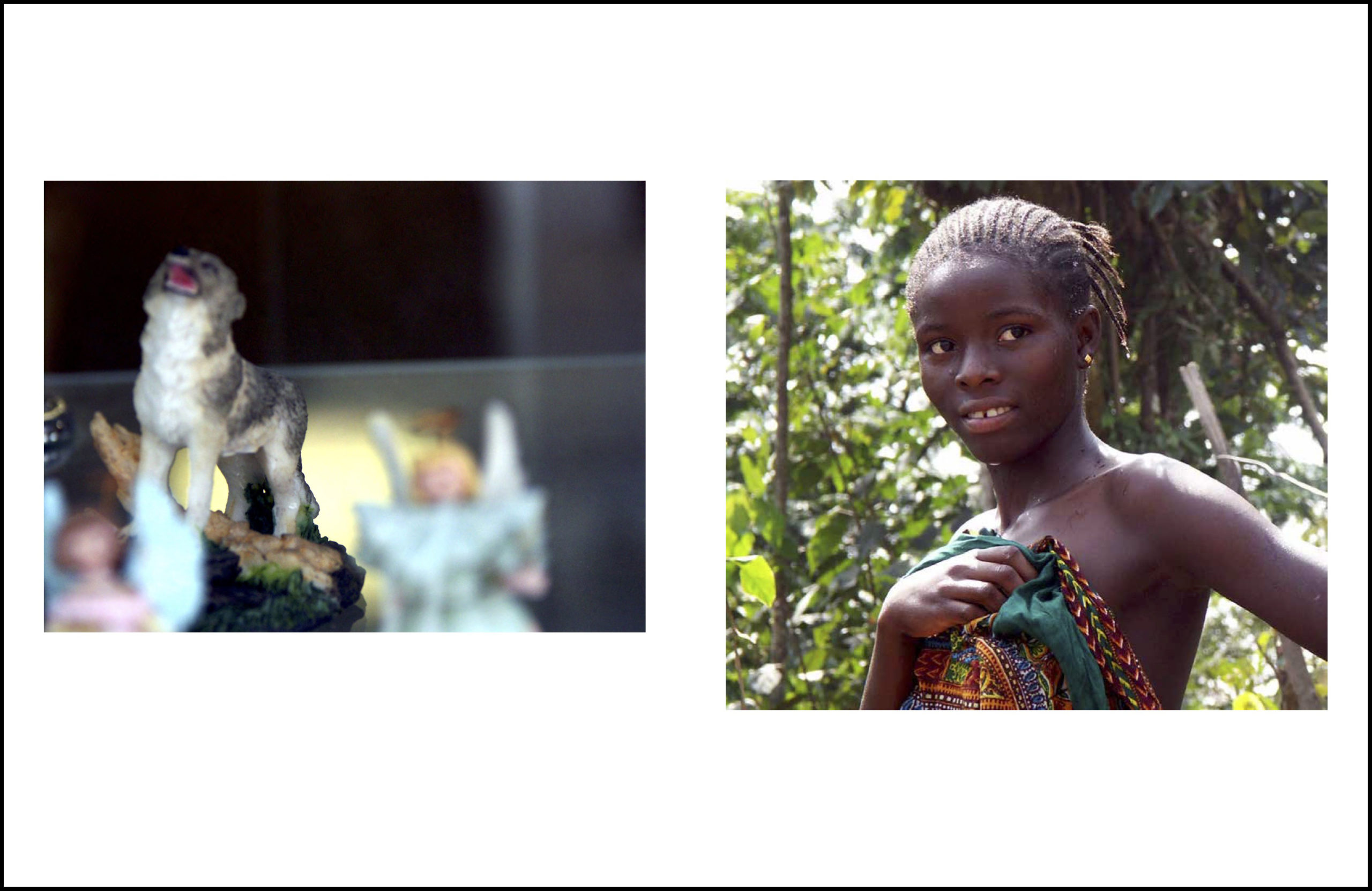

I love that fact that you flip through the project one after the other, and there isn’t a clear description telling you what each one is. The size of the magazine is very nice as it allowed us to use white space in the layout, which I thought was important. There’s a lot of air. And the photos obviously have stories for me. Each is quite special. One photo is of a young woman I met in Guinea, West Africa. I had been traveling through in the countryside, and part of the reason I was there was to understand better what drove people in countries like Guinea and around the world to leave the countryside for cities. We like to talk about how the majority of people of the world live in cities, over 50 percent, but I was trying to understand that statistic, because many people say it with great pride, but I thought there was something strange about that. I went out into the countryside of this place that was just stunningly beautiful, and yet so many people were leaving their villages for the capital Conakry. I was interviewing people and talked to her and she said most of the young men had moved away due to the idea of economic improvement. When I asked what this meant, she didn’t really have an answer. They go to the city looking for money, and in fact don’t find it. It is a complex situation. And all of this beauty and contradiction I read when I look at this image. These stories in my mind are not anywhere in text form, but I feel is embedded in the images somehow.

Your account from Guinea brings me to how the act of observation is integral to your design process, social interactions and how people live. As busy as you might be overseeing a big architectural office, and with other distractions vying for attention, do you make a point to set aside time for observation?

I try to as much as possible. It gets harder and harder as time goes by, but I do. And I’ve even done very unusual things. For example, I’ll fly into a place and instead of taking ground transportation of any kind from the airport to where I have to go, and I have a lot of time, I’ll walk instead. You sense a place in a very different way walking through parking lots, the leftover spaces in between parking lots, through loading docks of some strange big box building to get to another street. Crossing into some forgotten about residential district near the airport, and continuing to walk along larger roads trying to avoid dangerous situations with cars, along the side of the freeway. I’ve spent sometimes five hours walking. I’ve never had a rolling suitcase, only a shoulder bag. It allows me to be pretty mobile when I need to be. So that also allows me to observe things in a very different way. The problem these days is like many I held off on using my phone as a camera for so long, and unfortunately now am using it more and more. I liked holding a camera in my hand. It was heavier and you could feel its purpose. The phone has so many purposes, it’s just watering everything down. Furthermore, the reason you take pictures is so broad now—some for yourself, some for your friends, some for social media, some to record something you need to give someone. It’s now harder to remove the images from your phone/camera. I haven’t been carrying my camera as much as I used to and am a little sad about that.

An object with a single purpose infers more intention?

I want to get a typewriter too. I’m a really good typist. I learned at school at a very young age. And I learned on a typewriter. But that’s another example of an object with a single purpose. You can only write things. You can’t stop, push a key, and then browse the internet, like a computer does. So I’m thinking about reintroducing that to my life. A typewriter and getting my camera back out. This, by the way, doesn’t mean I don’t like computers and other technology, I just find that balance is important. And some of the photographs are talking about that—the difference between a handmade or authentic situation versus an artificial one.

During our initial meeting for this project, you told us about your collections of tchotchkes. In your essay, you say that “looking at man-made objects reveals our deeply seated motivations.” I’m curious as to how these two things might relate—collections of small, decorative objects as manifesting something deeper, and how might this relate to the photos in the project?

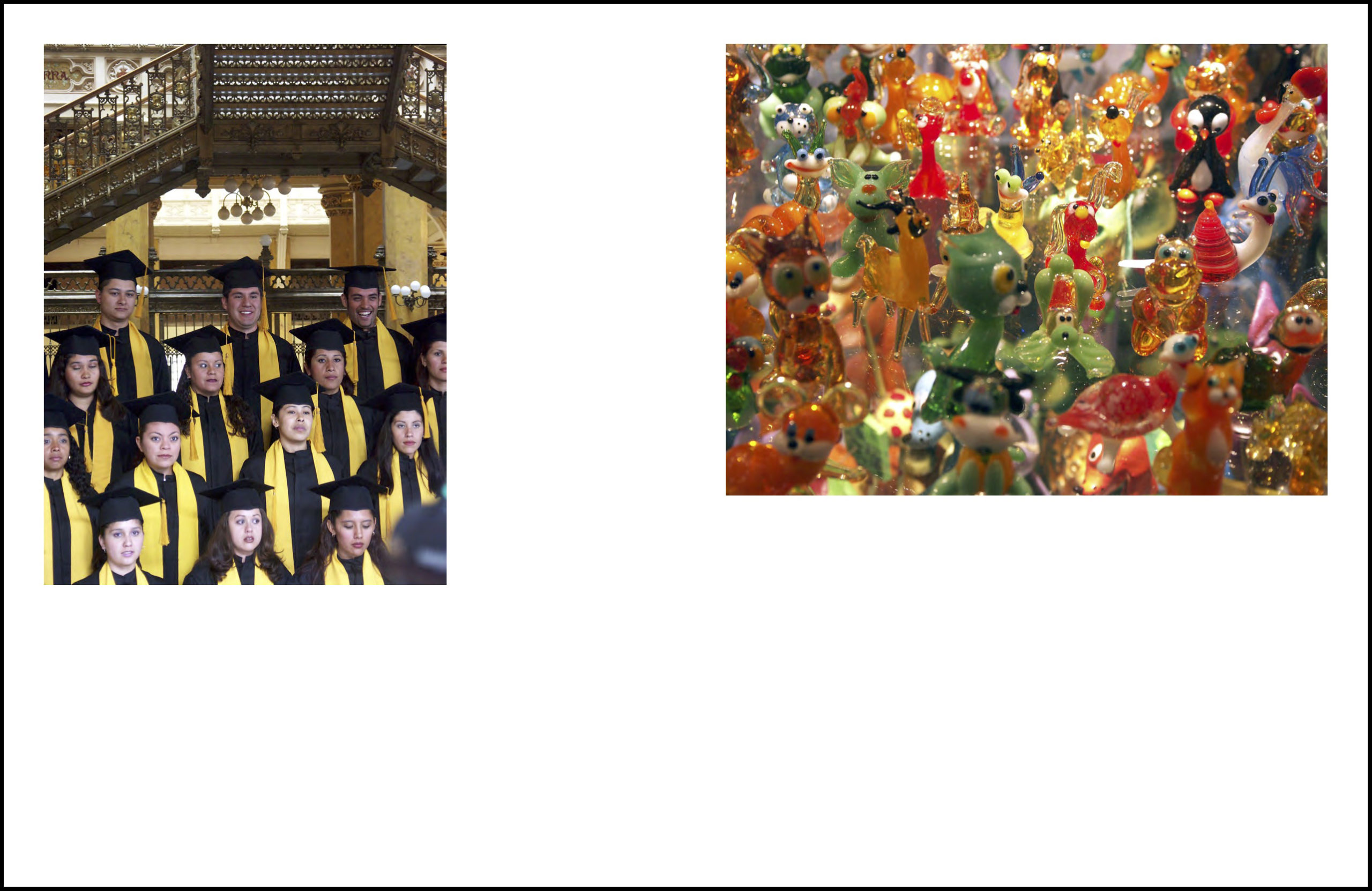

Well I think one of the reasons that we occupy our minds with art on all of its levels is that we want to learn something about ourselves and the people around us somehow. We want to dig deeper into our minds. Some people have dug into their mind for a long time, so they have to dig deeper. And that type of art can be more conceptual, and harder to envision what it is. But many people don’t have the luxury of digging into their minds every day, trying to understand their existence. They have to work like hell to put dinner on the table. Those people see art as something that is just letting them understand who they are and that they have some kind of significance. They don’t like to be alienated. It’s not art the way most of us would think of it, but to them it’s a form of art. An object, something that was made by someone or something else, and it tells them a little story that they can imagine. A lot of these things that I photograph, the kitsch objects that a large percentage of the world buys. And I say that, because everywhere I go, anywhere in the world, there are these things. Not just in Philadelphia, or Hamburg, or Venice. They’re in the most remote places. Clearly, they have significance for us. They tell stories of fantasy and romanticism, how we project our own desires, our own view of ourselves, into the objects that that fill our spaces. These are very inauthentic things that still are authentic, in a way. The trolls kissing on the bench are only objects, but similarly, all of us want to have that moment to have that kiss and not care if anyone is staring at us. Or it’s the ceramic dancers next to the women with similar make-up. They have the same eyes. Or the pictures of the graduates in Mexico City next to the glass figures from Krakow, Poland. The people are dressed the same, but each feels very different and special, just like all the glass animals. There’s something they are desiring, and if that doesn’t happen then maybe they will go out and buy these glass animals and fill their shelf.

Ultimately the meaning of these objects only comes in relation to people and the meaning these people impart on them?

That’s correct. And then the question is whether this is true for anything—conceptual art, vernacular architecture, contemporary architecture. It’s true for everything. But we just pretend there’s a civilized way of seeing things and a less civilized way of seeing things, but that’s in my opinion an artificial distinction.

Photo: Michael Grimm

In other publishing news, Snøhetta has just released a new monograph with Phaidon, covering 24 projects from the last decade and their evolution over time. Can you tell us more about that?

These are all built projects and furthermore all documented in their final forms, more so than the design process. As much as possible we try to capture images of our work with people involved. And this happens after building is completed and in operation. The emphasis is with trying to connect people with the building. And you need to think about all the levels of being, the way we exist in the world, in order to create the right environment. That is partially why I take all these pictures of ordinary people; there is value in observing ourselves doing seemingly simple things.

The projects in our book are from throughout our history and are divided into three themes to give further insight. The reason for this is that if we tried to unpack every project and all of its themes it would be hard to read. So we singled out some of the themes, for example politics in the space of society and civilization and how you negotiate that. Another is about generosity, and how if we are to socialize as creatures in larger civilization, there has to be generosity in order to survive. We try to create places that allow for that and collective ownership. The last has to do with our transdisciplinary process and how having multiple groups working together in a studio, as a collective, impacts the work. Many architects think they can do everything themselves and only need other people to tell them they’re right. We don’t do that. For instance, we have landscape architects working alongside architects, informing each other, arguing with each other, pushing the limits of what we do. We have branding and graphic design, we have product design and interior architects, all working together in a collective manner.

How important is publishing to Snøhetta’s practice? And did the office learn anything from the process of putting together this book that might benefit current or future architectural projects?

We have a history of not publishing. For a long time, we said, why should we publish? We design buildings. Other people can publish if they want. We didn’t want to self-author it. This was part of our feeling that we didn’t need a manifesto, but that was at the very beginning when we were younger. As we got older we realized that publishing was an important part of the process, not only for sharing our work with others, but also learning it ourselves. Because in making a book, when you are forced to put the work into words, and choose images to accompany these words, it allows you to look deeper into your motivations and the consequences of what you do. So we have started to publish more books recently. For example, two years ago we did a book on our work on the new San Francisco Museum of Modern Art. That book is different from our monograph because it focuses on only one type of project and our thinking behind making a museum. So we publish in part because there’s been greater demand, and the practical matter of more people wanting to understand our work. The books allow us to give them a certain degree of information. But the real value in publishing is about writing and words. Getting used to an editor, having a collaborative engagement with someone outside of the studio or our life, that pushes our thinking in many ways.