Lucie Fontaine is the type of person who will set up camp in your home and redecorate it with works collected from her very talented friends from every corner of the globe. She’s also the type of person that will use that residency as a jumping off point to pursue new projects and explore new possibilities, like the work she did for issue #24 of zingmagazine. She is, in other words, the best houseguest you could possibly ask for, the type that has something to offer and doesn’t offer it begrudgingly. In the excerpted interview included here, we discuss her work for zingmagazine, get a look at what makes her tick, and learn more about her process. She’s never asked to live with us, but if she did, we wouldn’t charge her rent. In fact, we would put her on an allowance, provide a daily turn-down service and source the finest fruits from around the world to put in a bowl on her dresser. Why, you ask. Because she deserves it. That’s why.

Interview by Oliver Nevin

Can you tell me what got you interested in postcards? Not that a postcard can’t be beautiful and well designed, but they are often quite mundane and painfully ubiquitous.

The starting point of the project was a show that I did in Summer 2013, in Paris, at Galerie Perrotin. I wanted to ask, what is a souvenir? Imagine when you travel, and you want to buy an object that somehow represents your experience, but it’s never real and authentic. The New York gadget that a tourist buys is something that a real New Yorker would never actually use. Or you encounter the paradox where you go to Venice and you get the real, authentic, miniature gondola and then you discover it was made in China. It’s like the souvenir becomes the tourist. It’s all about the idea of what is authenticity and what is identity and how does a souvenir interact with all of those ideas.

But this project is obviously different the one that you did at Perrotin. Can you explain the leap from that original idea?

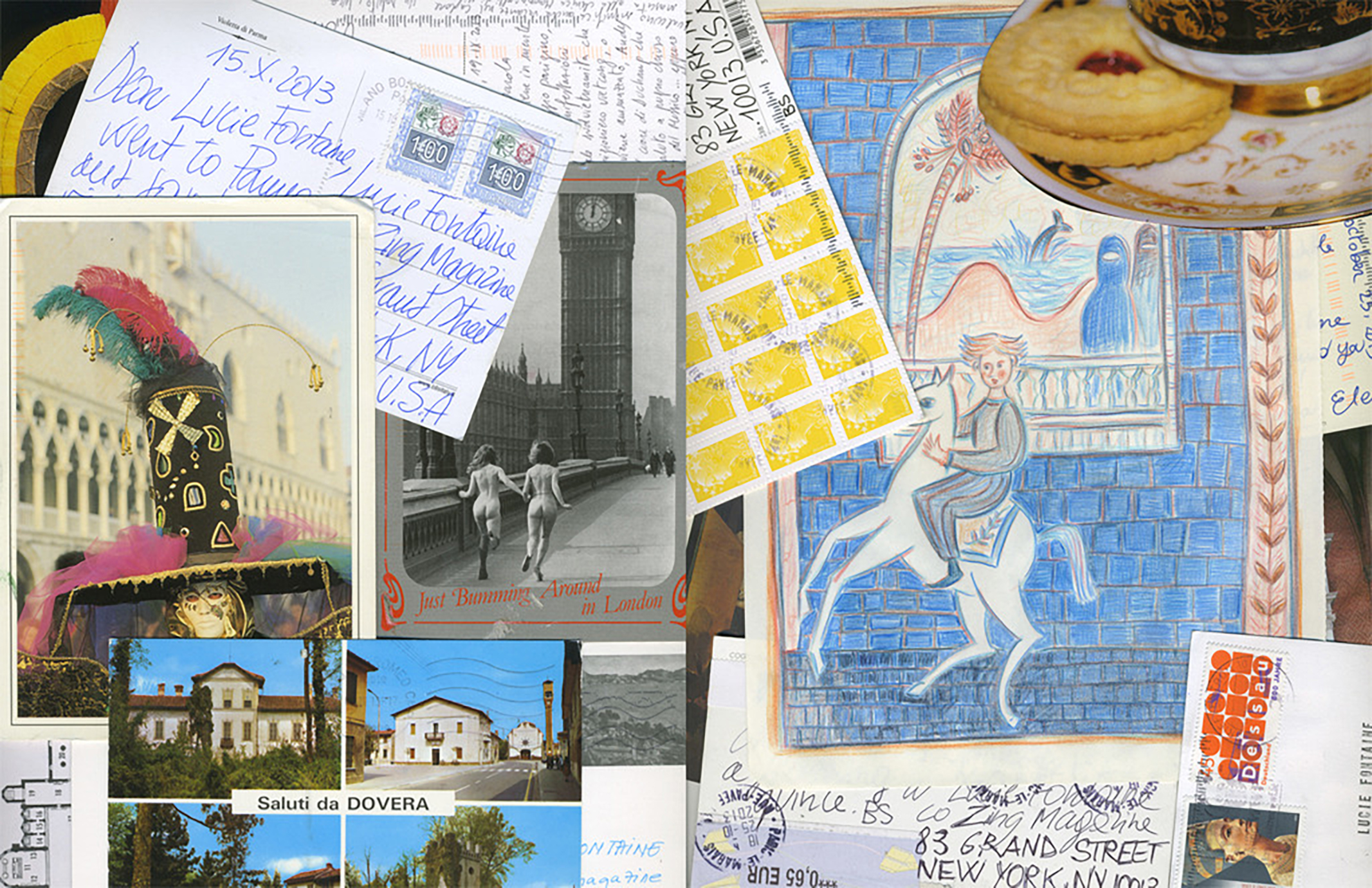

That show featured about 20 artists, and then I wanted to add a new chapter to the show by asking all the artists who participated in the project, plus a couple more people, to actually write postcards to me at the zingmagazine office.

You really wanted to dive deeper into that idea of giving life to an experience, and looking at all of the different things that make up that experience and how the many facets of our life are related to it?

The point of the souvenir is also that it’s not so important when you are there. But it becomes important the moment you get back home. And then of course it’s also associated with the idea of kitsch, but it’s part of the different meanings of what a souvenir is. All of a sudden, we were receiving postcards that were pictures of Paris, but they were sent from California, or they were anonymous, or they had been redesigned and altered by my friends, so we were able to add a layer of fictionality to this narrative of souvenir.

How many did you get?

I think around 40. I want to do a show with all of the postcards but I haven’t done that yet, because the postcard is something that you show in the house, and this idea of something intimate and domestic, especially domesticity, is very important for Lucie Fontaine.

I don’t think I’ve ever heard a creative proclaim to strive for domesticity. Why domesticity?

It’s something that has been a part of me from the beginning. I wanted to show works in a way that was not the usual setting. The first location of the Lucie Fontaine project space in Milan was actually an old and crappy barber store, where I never changed the floor or the walls and the atmosphere of the space remained the same. I was showing the works of young artists in this outmoded atmosphere, but it felt very intimate and domestic. The other two locations in Milan were also domestic spaces. And the Lucie Fontaine Space in Tokyo was inside a traditional Japanese house. There are also plans for a domestic Lucie Fontaine space in Tel Aviv too.

So you have a real commitment to the domestic? To be simple and raw instead of polished?

Yes, but it’s also about playing with the rules of the game and blurring boundaries between different roles in the art world. Another time that domesticity played an important role was during the show Estate I did at Marianne Boesky’s gallery uptown in summer 2012. The space was a beautiful townhouse on the Upper East Side. My three employees were living inside the gallery and transformed it back into a proper home. I decorated each room with the things that you would normally find in a house there, including antique furniture. But they were also artworks and complied with the themes of the show. You would enter a bedroom and you could see the wallpaper and flowers. But the wallpaper was a work, and the flowers were a work and the chair was a work, but it was very subtle. And then I had friends sending pictures and postcards that were helping to build the narrative of fiction in the show. So that’s another way that the postcard was something familiar.

I suppose that was like reaching the pinnacle of domesticity. Your artwork was quite literally in the home?

Indeed, and it was great. The first month my employees were installing the show, so the gallery was closed. When the show opened, they decided to stay and live there while the show was open to the public. So for two months, and especially in the second month, they were waking up each morning to tidy up their rooms before 10am, because visitors were coming in to visit the exhibition.

I guess it’s interesting to me to get a look at how a project like this starts as this sort of inkling, or seed of an idea, and ends up growing into something real and tangible.

The first time I started handling postcards was while I was living in the Marianne Boesky gallery/home. It wasn’t really until after the show in Paris, which was about tourism and travel, that I realized I should do an entire project built around them, but the seed was planted while living in that gallery.

That’s quite fortuitous.

It was there that I first received some postcards from some friends, and my employees had them displayed in the entrance where there was a big mirror. Because they were all actually received at that address, I was keeping a part of the fiction of the space intact, which was fun.

But you didn’t have to fake domesticity. Domesticity quite literally refers to matters of and/or relating to the home. It doesn’t feel very fictional to me.

I didn’t have to fake it, just preserve it. I remember there was one artist friend, he came to visit the show one Saturday afternoon, and he said that when he first entered he thought he was in the wrong place. He said, “Oh shit, this is wrong, I just broke into someone’s home.” After he left and double-checked the address, he realized that was actually the right place. That’s exactly what I wanted.

Do you feel like you were able to stay true to your commitment to authenticity with the project in zingmagazine?

I do. I think it’s all about the idea of what is authenticity and what is identity and how does a souvenir play with and interact with those notions. So at the show in Paris, I wanted to install it as a bazaar. I didn’t want it to look standard, like a white cube installing, but more like overabundance, and to develop a much denser dialogue with the pieces. I think the way those postcards were assembled in the magazine really ended up staying true to that idea. When you turn the pages, you are in the postcards, surrounded by them, and I think that gives the reader a sense of being surrounded by the experience and significance of each postcard.

Well I’m glad you were able to achieve your vision for this project. Thanks so much for taking the time, I enjoyed the conversation.

You’re welcome, it was my pleasure.