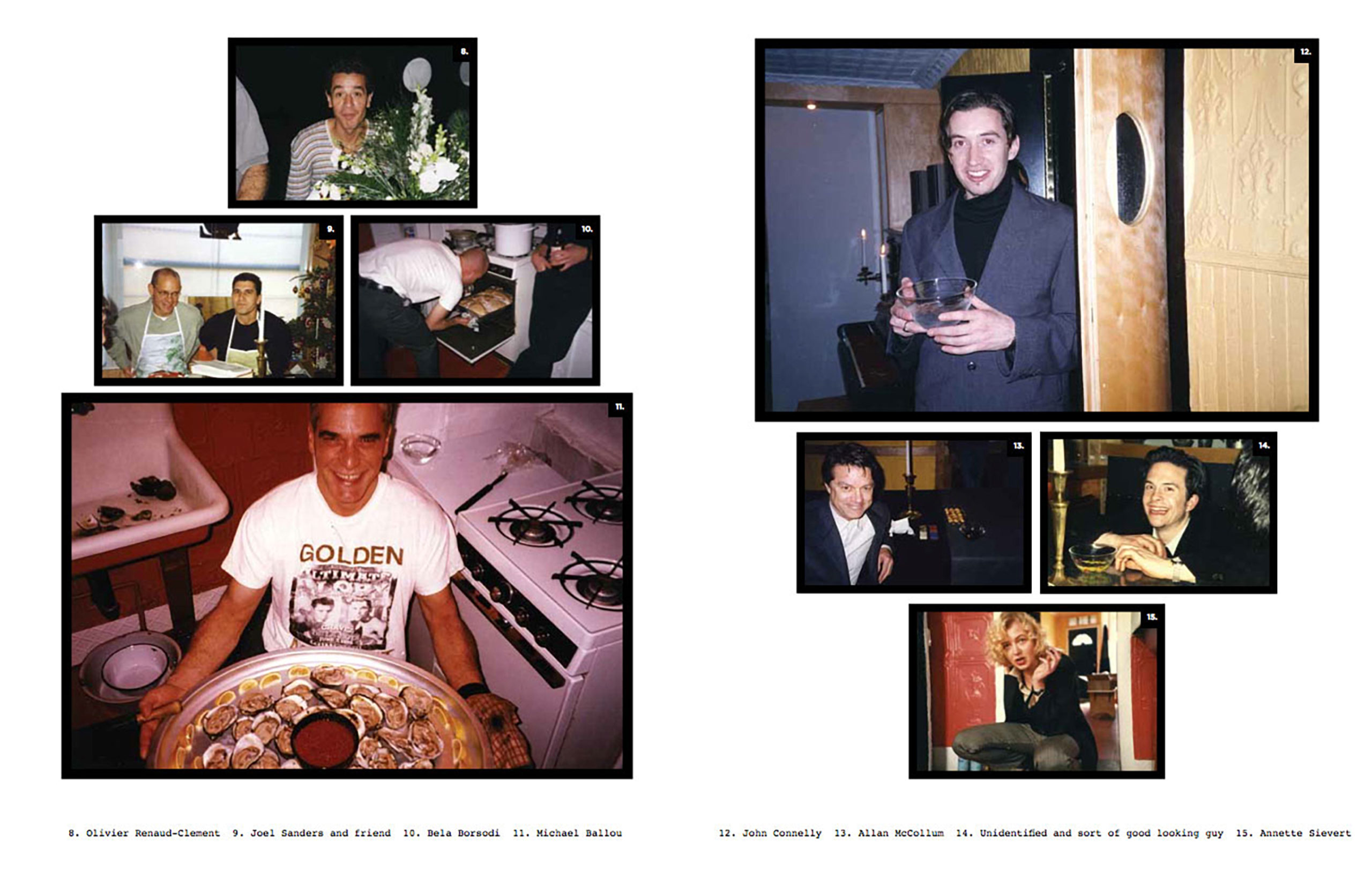

A page from Cocktail Hours at The A-Z Brooklyn NY 1996-1998, curated by Andrea Zittel for zingmagazine 23

Andrea Zittel casts a critical yet sensitive eye upon society and its constructs. She questions the value and implementation of social design, both the psychological and physical, and aims to provide insight and solutions to these questions through her artwork. Her investigations have culminated into an incredible range of artistic output, from modular living units, egg incubators, and functional textiles, to the creation of floating islands, desert communes, and interactive public art installations. The nature of Zittel’s artwork calls for utility and interaction, but simultaneously values aesthetic autonomy and personal solitude. This dichotomous relationship between form and function, public and private, is indicative of how her work effortlessly straddles the lines between art, architecture, and design. Her project in zingmagazine issue 23 documents the usage of some her early prototypes, and provides a glimpse into her social circle of the time. Rachel Harrison, Wade Guyton, Maurizio Cattelan, Gregory Volk, Roberta Smith—these are just a few of the people who could be found in Zittel’s three-story row house on Brooklyn’s Wythe Avenue on Thursday evenings, in a time before the borough became the creative hub that it is today.

Andrea and I began to exchange emails back in March, when she was in the midst of organizing and installing an exhibition of her “Aggregated Stacks” at the Palm Springs Art Museum. In April she welcomed the first of two groups of people to her A-Z West outpost for open season in Joshua Tree, California to facilitate their personal explorations in art, life, and self. She is currently preparing for another solo exhibition, The Flat Field Works, at the Middleheim Museum in Antwerp. Her ability to maximize efficiency and productivity is something we all strive to achieve, but her capacity to do so creatively and philosophically is beyond exceptional.

Interview by Hayley Richardson

Your A-Z enterprise began in a small row house in Brooklyn in the 90’s, known as “The A-Z.” This was the site for the popular Thursday cocktail hours in which local artists and people from the neighborhood would gather socially and test out your new living systems. Your project in zingmagazine 23 features candid photographs from these congregations, and these photos can be seen affixed to the walls of the apartment. Your work calls into question the usefulness or function of space and day-to-day objects, so I am curious if these photographs, these memories, serve(d) an important purpose in your routine.

I know my work has often been described along the lines of functionalism—but I’m actually not so interested in practical function as I am in psychological function and things like social roles, or value systems. So The A-Z, my Brooklyn rowhouse/storefront functioned as a testing grounds for these experiments—and as a space that allowed my works a kind of autonomy from traditional exhibition spaces. Thinking about various forms, independence or self-sufficiency has always been an important focus—both back in Brooklyn and here at A-Z West in the desert where I have tried to create a center outside of any existing centers.

In trying to create a “center” in Brooklyn we created our weekly cocktail hours, which were basically open to anyone who was willing to attend. I loved the cross sections of people who would find their way through the doors, including other neighbors on the block, fellow artists and curators, critics, gallerists and then the more established artists who made the trek out from Manhattan. Back then Williamsburg was considered totally remote and peripheral to the art world in Manhattan, so I remember being pretty blown away when people like Jerry and Roberta made the trip out.

And the photos were really just a way of cataloging the journey—a sort of sentimentality of sorts. My grandma had photos of her grandkids, and dogs and horses on the wall of her ranch-home. I had photos of my friends and people who made it out to my nook in Brooklyn. As I look back at these images now I think it’s sort of amazing to see my peers and myself in these early years of infancy.

Are there any memories that you are particularly fond of from these gatherings that you’d like to share?

We used to try to think of fun things to do for the cocktail evenings—I remember once Mike Ballou prepared an amazing spread of raw oysters. I can’t quite remember why, but I seem to recall that he did this while wearing boxer shorts. And we found a book of personality tests, so sometimes we would drink cocktails and give each other the quizzes so that we could compare personalities. Also I had a huge 80-pound weimaraner named Jethro who we used to have to muzzle because he would go sort of crazy with all the people around. I’m still really grateful to everyone who tolerated my really annoying dog.

It has been 15 years since you moved to Joshua Tree and began A-Z West. Can you talk about how this endeavor has evolved since its initiation, both for you personally and for the people who have engaged with it? Has anything ever unexpectedly occurred at A-Z West that had a lasting impact on how you view the project conceptually, or how it functionally operates?

Sure—talking about the community at A-Z East, it makes me realize that in a lot of ways A-Z West has actually become very similar, though this wasn’t my intent at all in the beginning. Originally the two projects were related in that they were both meant to be places where I could make prototypes, live with them, and make them public in their original contexts. But the difference between the two was that I really wanted to have more time alone and more removal from the art world out at A-Z West. I’m never bored and rarely lonely. When I first moved to the desert I could go days without seeing anyone. The phone would ring and I would try to answer it, but find that I had lost my voice from not speaking to anyone in several days.

Now at A-Z West I have a full-on studio with a group of people who I work with. We have open season in the Wagon Station Encampment twice a year (our open season actually starts today [April 20]—and throughout the course of the day ten people are going to arrive to spend various amounts of time here) and A-Z West also has a guest house, and two shipping container apartments for people who come to work on projects. So the desert has become a really active community with lots of activity and people coming and going.

Ultimately A-Z West, similar to A-Z East, has become an entire organism that is bigger than myself and bigger than my own life. I think that it’s super interesting when this happens—and at some point I can see it growing into something that may have a life of its own that will allow me to go explore some other new context—maybe starting with something more remote all over again. (Though If I do that—I think I’ll work hard to keep the next project a little more low key!)

It is interesting you say this because your work has this tension between a desire to be communal and social, and a desire for isolation and escape. I think this is a universal dynamic that all people grapple with inn some way. Is this a deliberate pattern, where your time in solitude is like a hibernation period that brings forth new ideas about public/collective life?

It isn’t deliberate, or at least it isn’t something that I thought about and planned to happen—but I feel that you are completely right about this being something that we all struggle with. Trying to find a balance between private and public, individual and collective. But I have noticed that being alone for periods of time helps me to appreciate and value people more. So that is the beneficial part of being able to create distance.

You are currently preparing for a show at the Palm Springs Art Museum Architecture and Design Center, in which you collaborated with the museum’s curators and selected works from the collection to commingle with your “Aggregated Stacks.” According to the information presented on the museum’s website, your focus in on integrating your Stacks with Native American weavings. What was your thought process in selecting from the collection? Will other, perhaps three-dimensional, objects come into play in this exhibition?

The collection actually had a lot of different works that I was interested in—for instance it has really amazing Albert Frey archives that include all of his receipts and bank statements and personal photos! But the work in the exhibition really had to do with the space itself—which is a newly restored Stuart Williams bank building. It’s a really wonderful piece of mid century architecture that is strongly tied to the grid. I knew right away that a body of my own work titled “Aggregated Stacks” would tie in perfectly with the architecture—these works also are based on a grid, but theirs is more of a decomposing grid where everything is a little off kilter.

Then culling through the museum’s collection I was really drawn to the textiles. I used a lot of Native American weavings in the show, and also some mid-century table cloths and a piece that I think may have been a curtain at some point, as well as a contemporary tapestry by Pae White. All of the textiles are arranged in a gridded composition on large pieces of carpet. So the textiles aren’t three dimensional—but displaying them on the floor does alter their reading and in a sense gives them a more spatial quality that I’ve been really interested in lately.

In a recent series of art21 segments, you mention how the lines between art and design are continuously blurred and redrawn and that your aesthetic is constantly changing. How would you describe where you are at right now, aesthetically and along the art/design spectrum?

Even though I’m a Virgo and super practical person, I feel like my work has become increasingly existential and philosophical over the last ten years. There has been a strong graphic quality in my work from the start—and I’m still going with this, but also trying to evolve toward a new level of restraint or subtlety. And I’m sure that all of this is coming directly out of some of my changing views about life—I’ve always had strong sociological interests in things such as rules and social systems—but as I get older I find myself taking some of those questions a bit deeper into questions about reality or even consciousness itself.

Yes, I’ve read about how you feel rules and structure are important in generating creativity. Do you still feel this way? Can you talk more about these new questions/thoughts you’ve been having?

Yes, I totally still feel this way—I think that we can use rules to “liberate” ourselves in a sense. Sometimes when everything around us becomes totally overwhelming and oppressive the only way we can make sense of freedom is to create a set of rules or limitators for ourselves that are smaller than the larger, socially imposed restrictions.